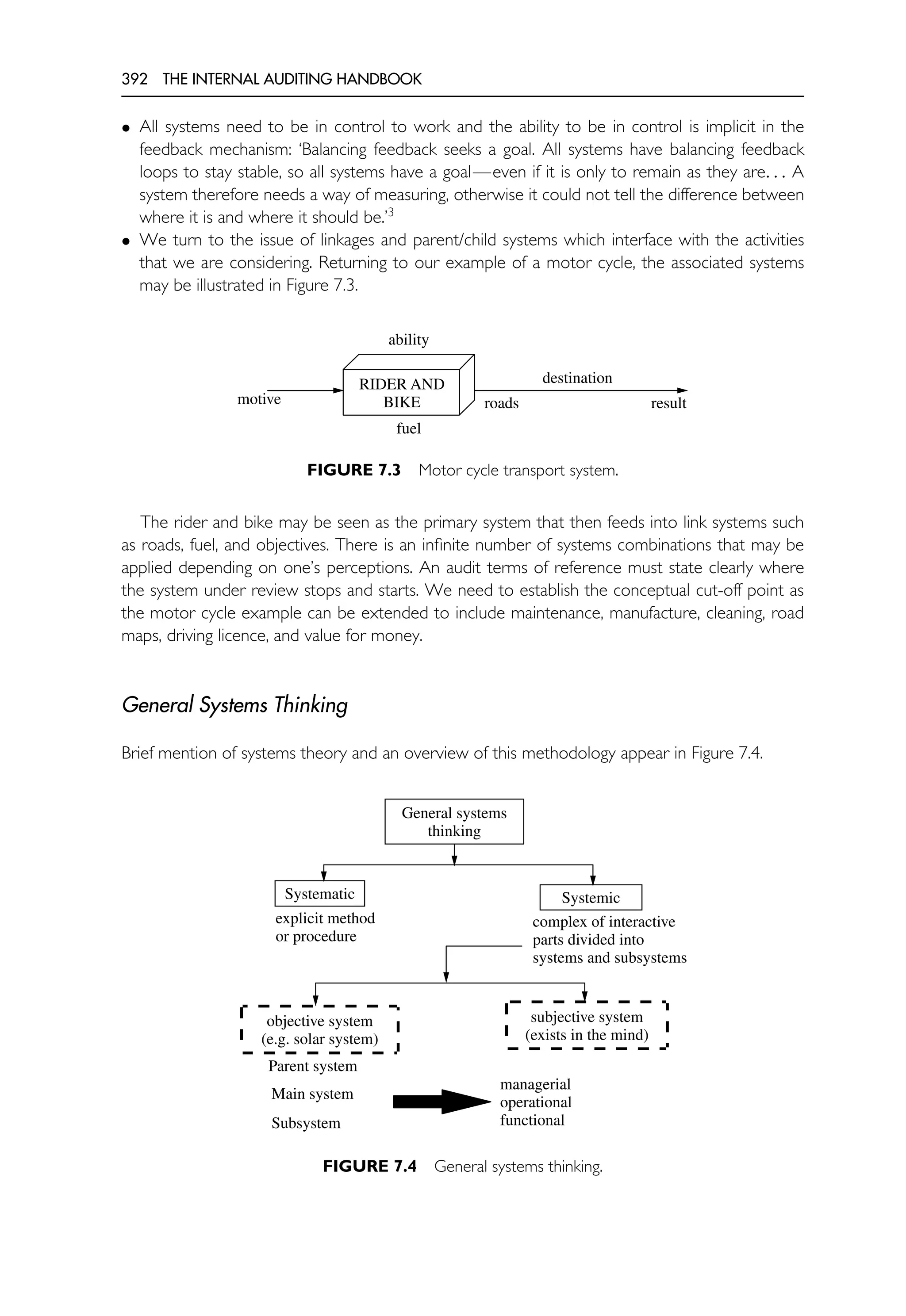

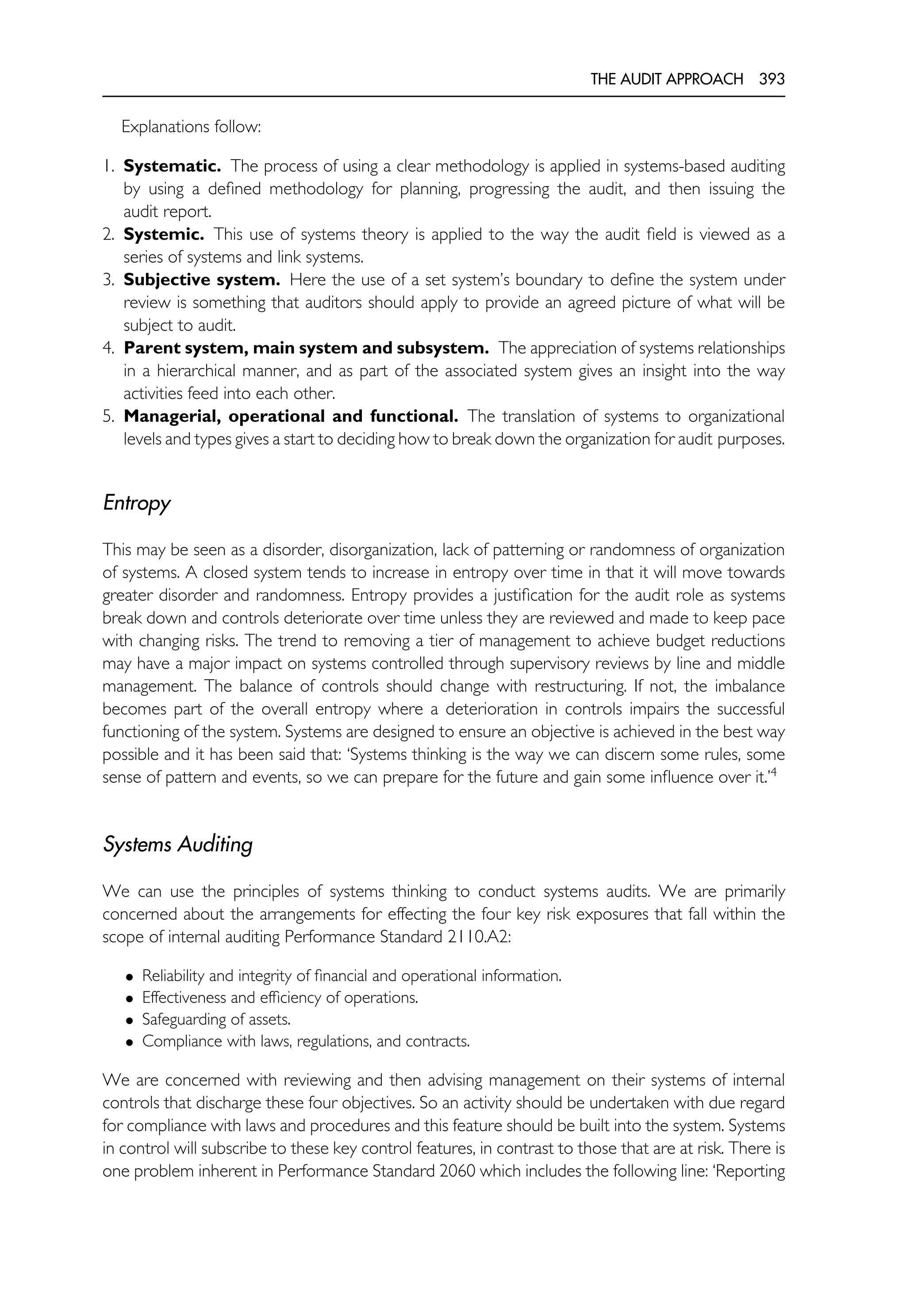

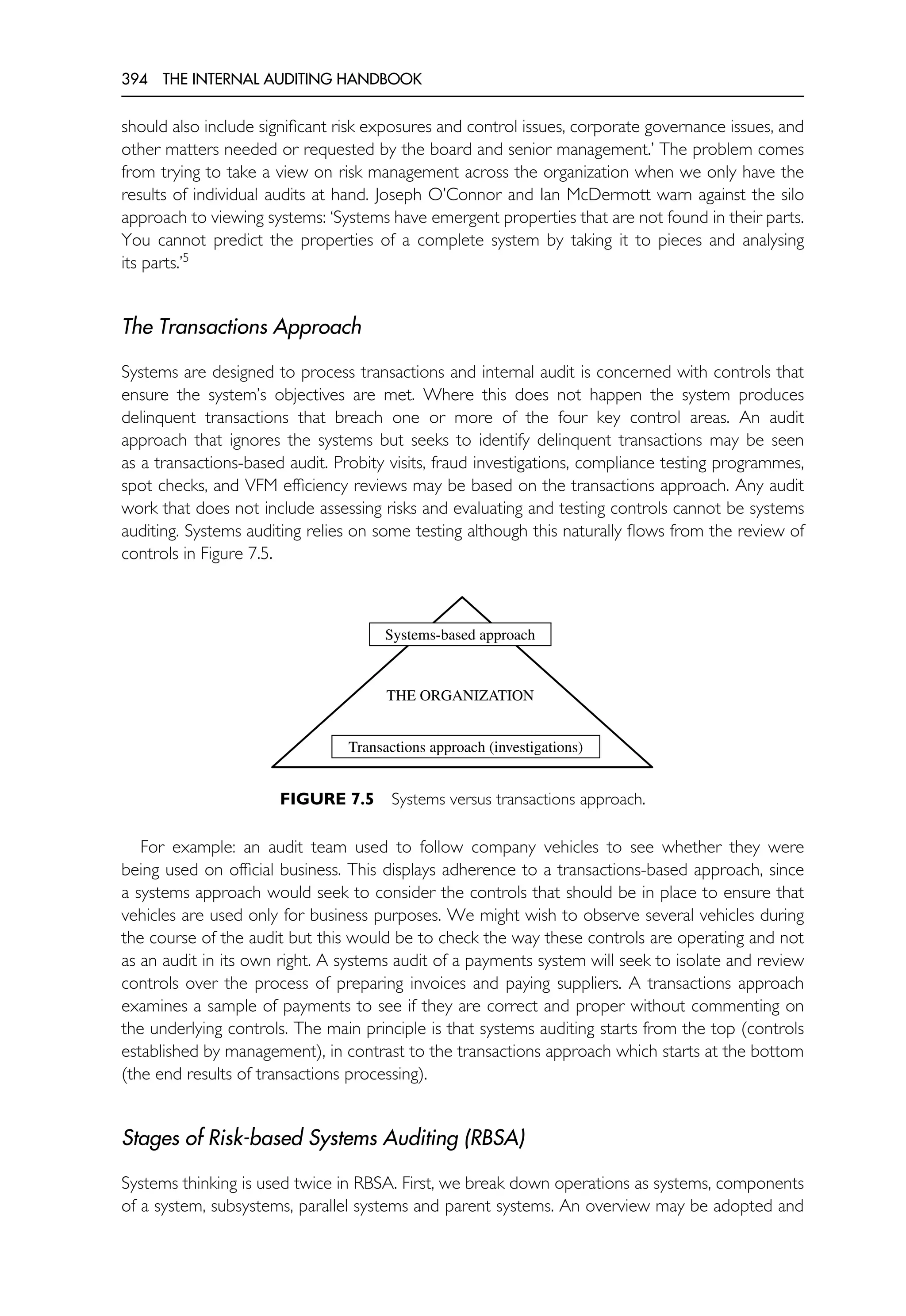

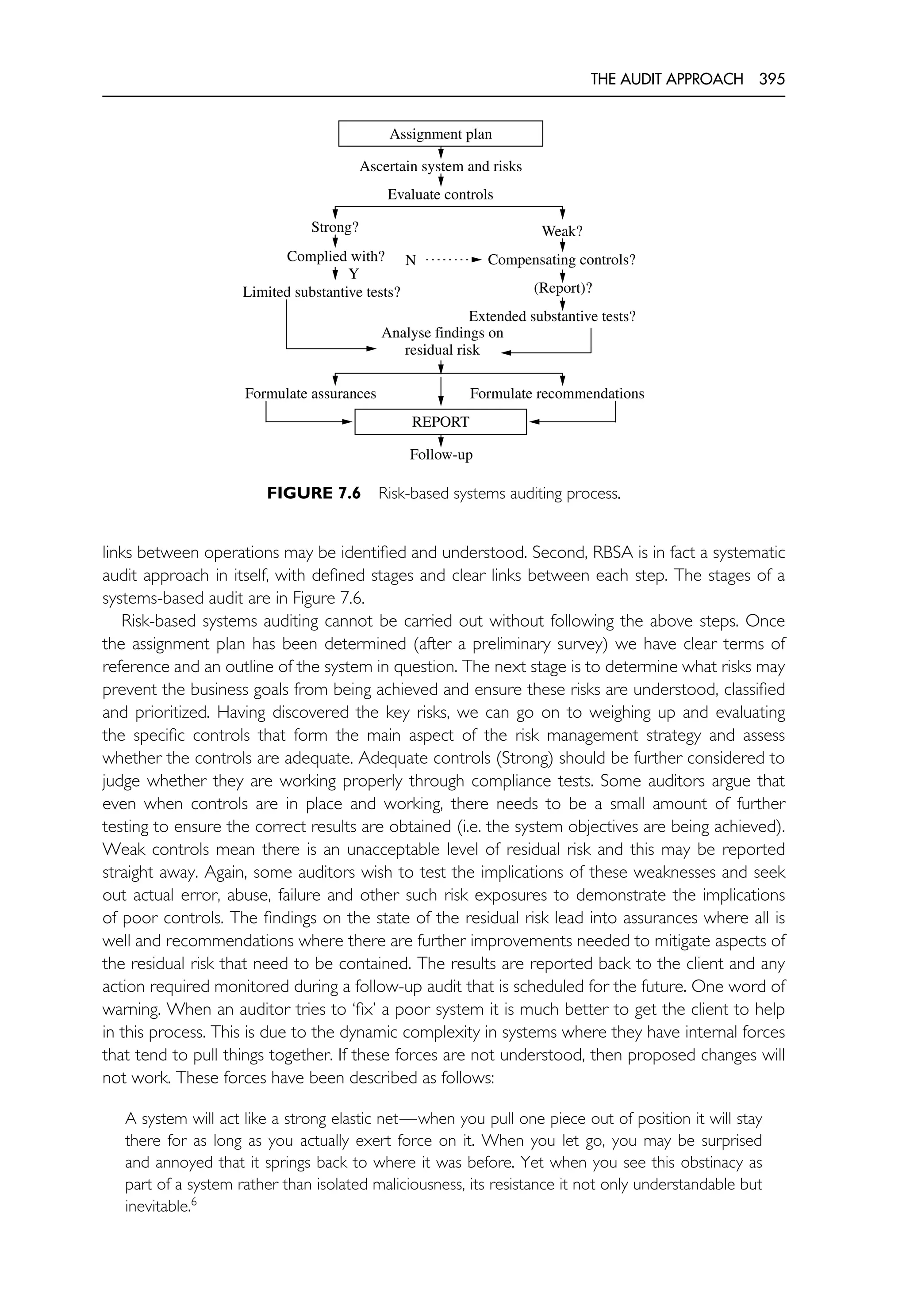

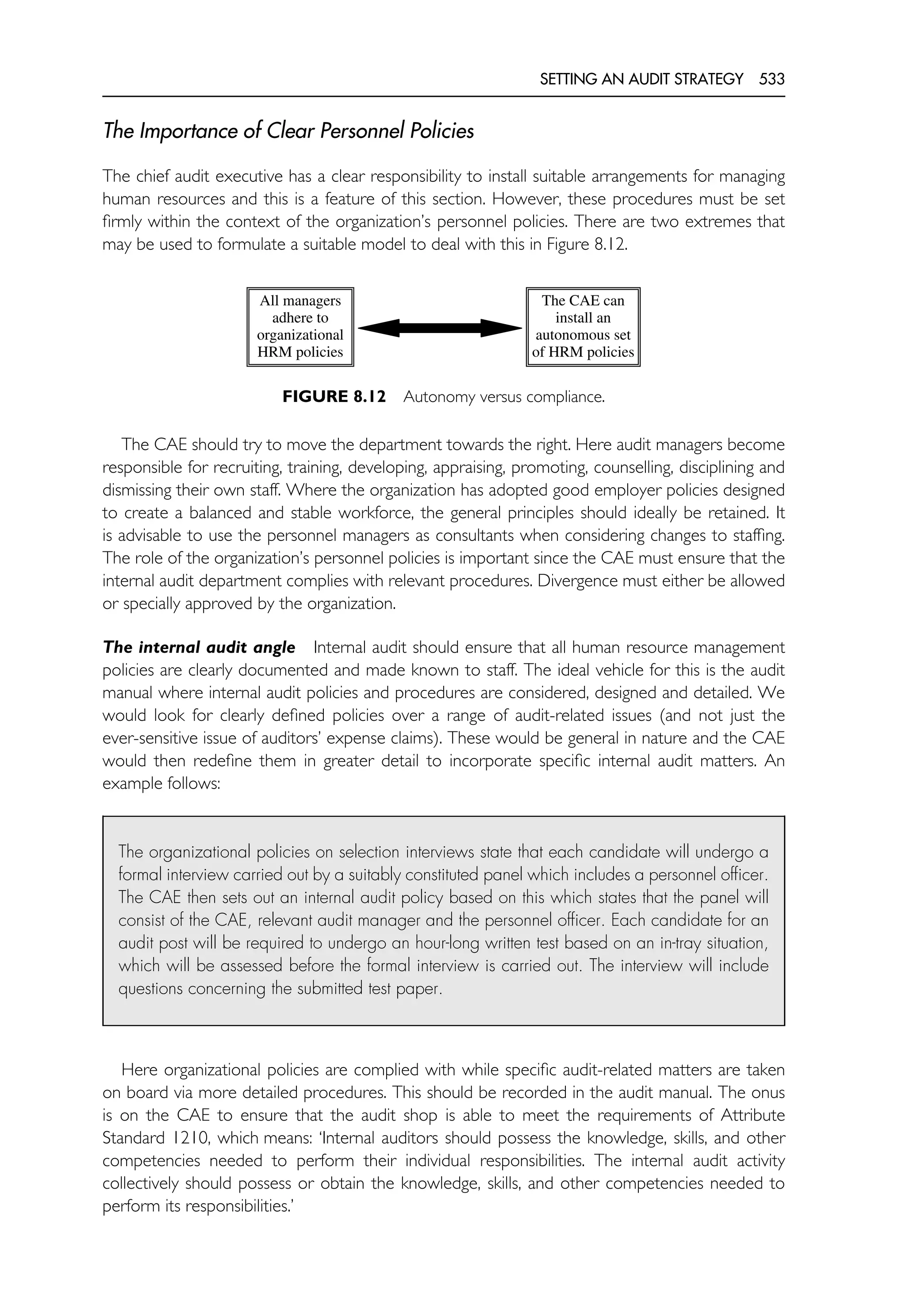

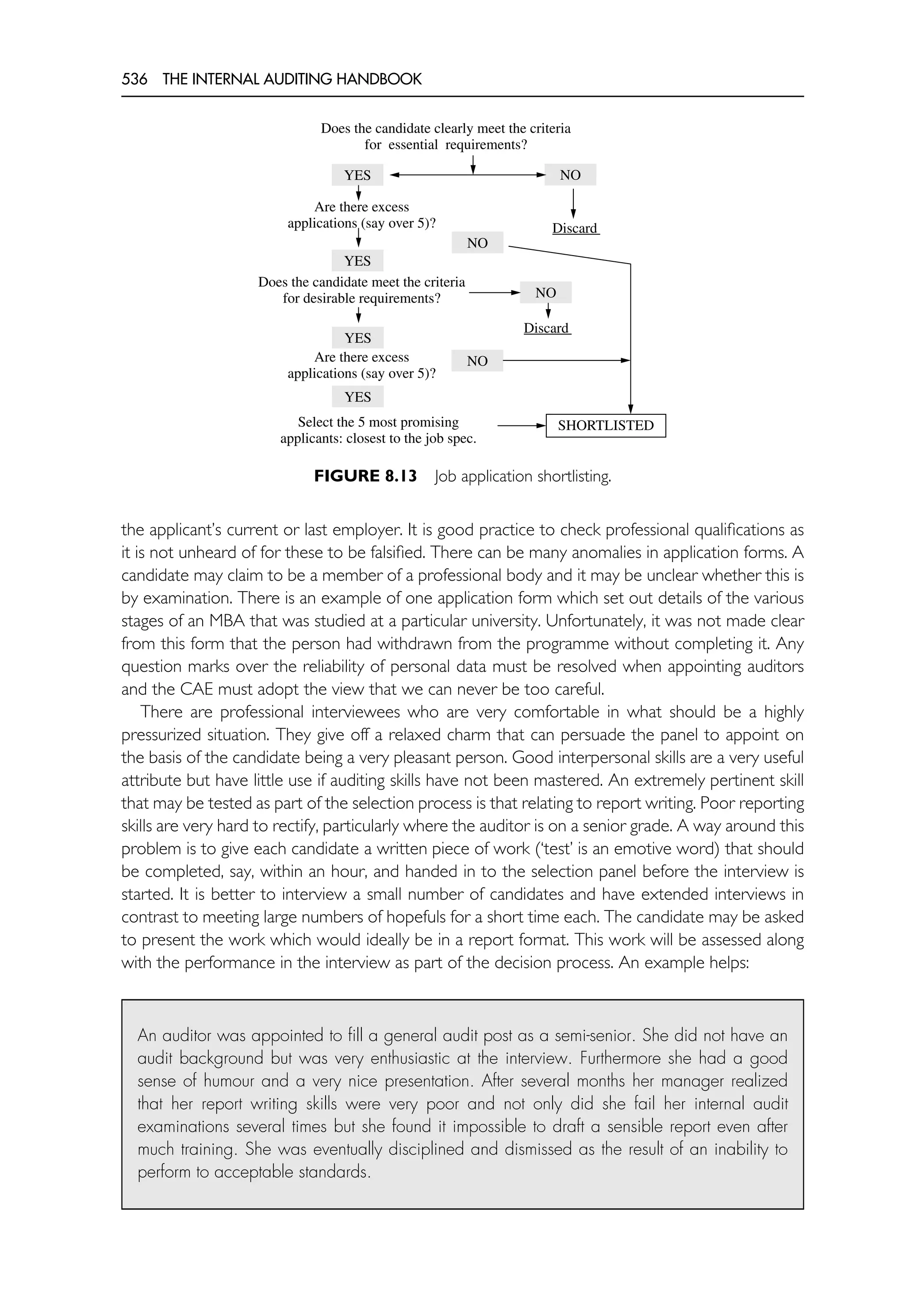

This document provides an introduction to the second edition of The Internal Auditing Handbook. It notes that significant changes have occurred in internal auditing since the first edition in 1997, with auditors now playing a more strategic role in areas like corporate governance and risk management. The new edition reflects these developments with additional chapters on governance, risk, and controls. It incorporates a variety of perspectives from thought leaders to provide a well-rounded view of the evolving audit context and role. The reasoning is to understand how internal auditing fits within the wider corporate agenda before addressing specific audit tasks. The goal is to help readers appropriately respond to changing expectations of the profession.

![CORPORATE GOVERNANCE PERSPECTIVES 47

The UK Experience

Cadbury The development of corporate governance in the United Kingdom provides a

remarkable synopsis of the topic as it has evolved and adapted, slowly becoming immersed into

the culture of the London business scene. One summarized version of this development (drawing

on an account of Sir Adrian Cadbury’s involvement after his report had been out for ten years)

appears as follows:

Two important cases hit the headlines over a decade ago (Coloroll and Polly Peck) where major

problems were concealed in the accounts presented to shareholders, investors and the City. In

May 1991 the London Stock Exchange, the Financial Reporting Council and accountancy bodies

commissioned Cadbury and other committee members to review the problems and ensure

confidence in the London markets was not damaged at all. This was the first opportunity for

the business community to engage in an serious and open debate on the topic of governance

and accountability. Just as the committee got to work, the BCCI and Maxwell cases broke

and the committee’s work took on a much higher profile, as London’s reputation as a reliable

trading centre was severely dented. The Cadbury report appeared to a barrage of protest as

the business community felt attacked by rafts of new regulations. The 19 items in the code

represent best practice guides that at first were resisted by several listed companies. The Code

covers 19 main areas:

[1] The board should meet regularly, retain full and effective control over the company and

monitor the executive management.

[2] There should be a clearly accepted division of responsibilities at the head of a company,

which will ensure a balance of power and authority so that no one individual has unfettered

powers of decision.

[3] The board should include non-executive directors of sufficient calibre and number for their

views to carry significant weight.

[4] The board should have a formal schedule of matters specifically reserved to it for decision

to ensure that the direction and control of the company are firmly in its hands.

[5] There should be an agreed procedure for directors, in the furtherance of their duties to

take independent professional advice if necessary at the company’s expense.

[6] All directors should have access to the advice and services of the company secretary,

who is responsible to the board for ensuring that board procedures are followed and that

applicable rules and regulations are complied with.

[7] Non-executive directors (NED) should bring an independent judgement to bear on issues

of strategy, performance, resources, including key appointments and standards of conduct.

[8] The majority of NEDs should be independent of management and free from any business

or other relationship which could materially interfere with the exercise of independent

judgement, apart from their fees and shareholdings.

[9] NEDs should be appointed for specified terms and re-appointment should not

be automatic.

[10] NEDs should be selected through a formal process and both this process and their

appointment should be a matter for the board as a whole.

[11] Directors’ service contracts should not exceed three years without shareholders’ approval.

[12] There should be full disclosure of a director’s total emoluments and those of the chairman

and highest paid UK directors.

[13] Executive directors’ pay should be subject to the recommendations of a remunerations

committee made up wholly or mainly of NEDs.

[14] It is the board’s duty to present a balanced and understandable assessment of the

company’s position.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/theinternalauditinghandbook-220527125740-de0fa305/75/The-Internal-Auditing-Handbook-pdf-60-2048.jpg)

![48 THE INTERNAL AUDITING HANDBOOK

[15] The board should ensure that an objective and professional relationship is maintained with

the auditors.

[16] The board should establish an audit committee of at least three NEDs with written terms

of reference which deal clearly with its authority and duties.

[17] The directors should explain their responsibility for preparing the accounts next to a

statement by the auditors about their reporting responsibilities.

[18] The directors should report on the effectiveness of the company’s system of internal control.

[19] The directors should report that the business is a going concern, with supporting

assumptions or qualifications as necessary.

Implicit in the code are several key considerations:

• the need to split the boardroom roles of chair and chief executive to ensure the dominance

that was a feature of the Maxwell case less likely.

• the need to stop the unfettered abuse through excessive and unstructured directors’

remuneration and benefits.

• the need to ensure there are good controls in operation.

• the need to ensure better oversight through an audit committee of NEDs.

Cadbury went on to describe the underpinning principles behind the code:

1. Openness—on the part of the companies, within the limits set by the competitive position,

is the basis for the confidence which needs to exist between business and all those who have

a stake in its success. An open approach to the disclosure of information contributes to the

efficient working of the market economy prompts boards to take effective action and allows

shareholders and others to scrutinise companies more thoroughly.

2. Integrity—means both straightforward dealing and completeness. What is required of

financial reporting is that it should be honest and that it should present a balanced picture of

the state of the company’s affairs. The integrity of reports depends on the integrity of those

who prepare and present them.

3. Accountability—boards of directors are accountable to their shareholders and both have

to play their part in making that accountability effective. Boards of directors need to do so

through the quality of information which they provide to shareholders, and shareholders

through their willingness to exercise their responsibilities as owners.81

Rutteman The 1993 working party chaired by Paul Rutteman considered the way the Cadbury

recommendations could be implemented. The draft report was issued in October 1993 and

retained the view that listed companies should report on internal controls but limited this

responsibility to internal financial controls. The final report issued in 1994 asked the board to

report on the effectiveness of their system of internal control and disclose the key procedures

established to provide effective internal control. In one sense this was a step backwards in

that internal financial controls meant those systems that fed into the final accounts but did

not extend the reporting requirements to the business systems that supported the corporate

strategy. Reviewing, considering and reporting on internal financial controls does cost extra

money but large companies have traditionally been examined by their external auditors. The

task of reviewing financial controls was fairly straightforward although the need to assess

and report on their ‘effectiveness’ posed some difficulty. This is because controls can never

be 100% effective—sometimes, something may possibly go wrong. Corporate governance in

focusing on the behaviour of the board and financial controls was headed for a back seat in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/theinternalauditinghandbook-220527125740-de0fa305/75/The-Internal-Auditing-Handbook-pdf-61-2048.jpg)

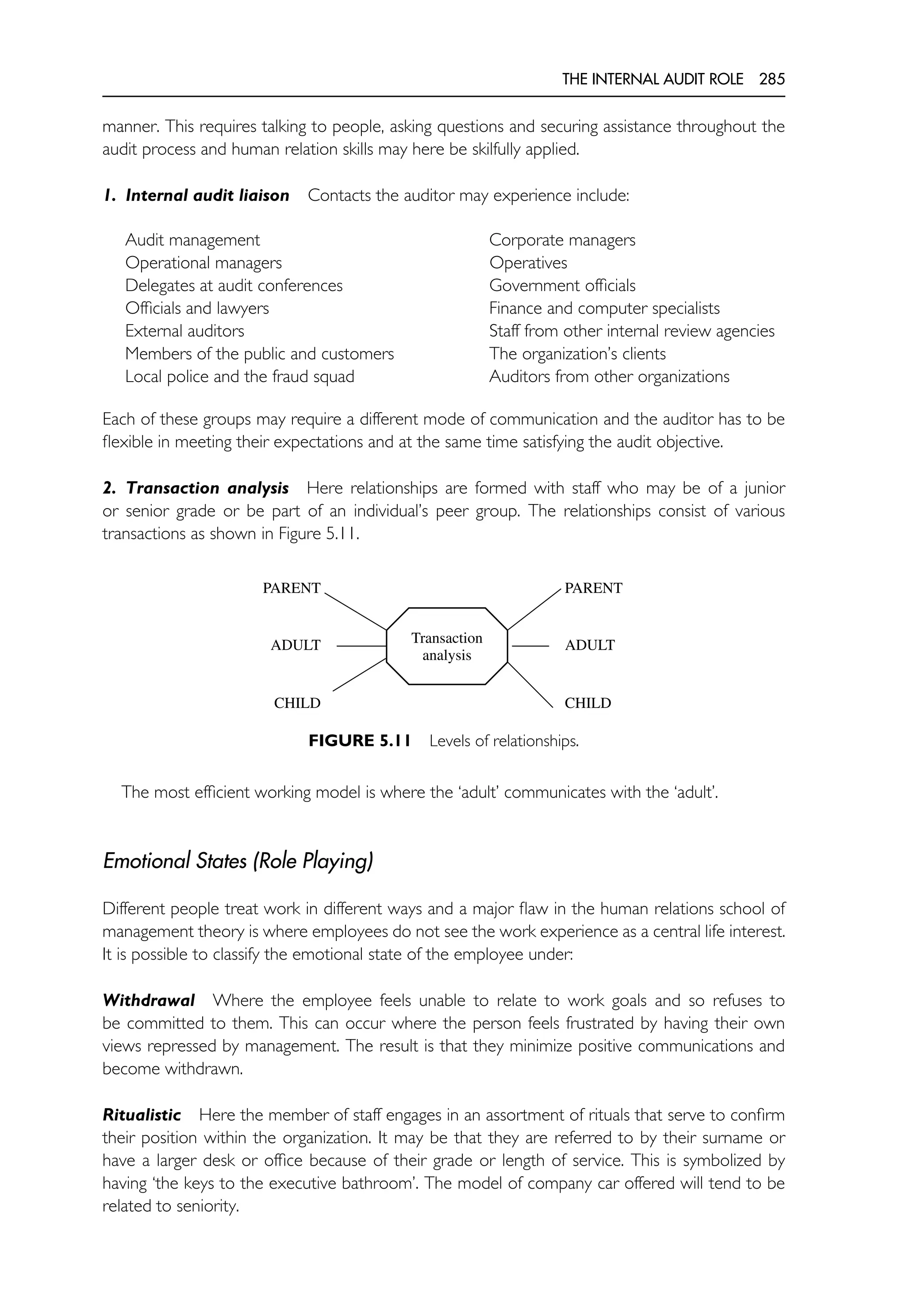

![286 THE INTERNAL AUDITING HANDBOOK

Pastimes This person sees work as an interesting pastime and may spend much time gossiping,

securing favours and generally enjoying the social side of work. An auditor operating in this mode

will typically work on never-ending fraud investigations following the audit nose and tracking

down the perpetrators in a style reminiscent of that used in detective stories. Low productivity,

long lunches and an extensive network of work friends and contacts are normally a feature of

this approach.

Games Where the work culture is geared to excessive competition then a games culture may

become the norm. This views success as dependent on another colleague’s failure. Employees

spend time catching each other out, gaining the upper hand and generally getting into favour with

the power figures within the organization. Many major decisions are made with the aim of scoring

goals against colleagues. An individual’s own goals may at times coincide with organizational

objectives but they may also serve to suboptimize performance. Overreliance on one main

performance indicator, e.g. ratio of recoverable to non-recoverable audit hours worked, may lead

to managers distorting results and so playing games.

Work activity This emotional state may best serve the organization in that it occurs where

the individual is geared into work goals and has a clear well-defined purpose that he/she relates

to. They are not easily side-tracked from these goals and the social aspects of working for an

organization assume second place to getting the job done in an efficient manner.

Dealing with People

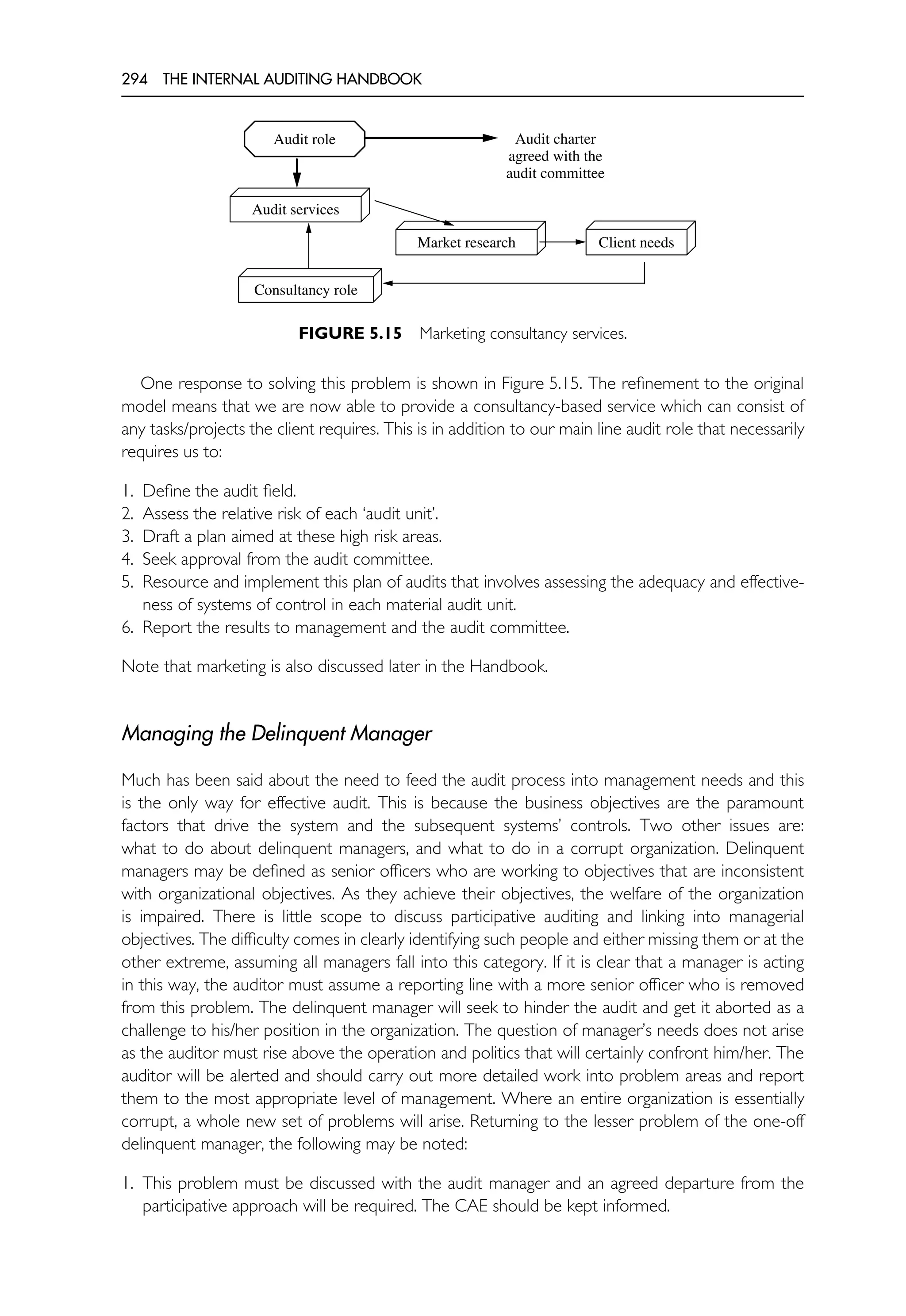

There are certain obstacles that the internal auditor may come across when carrying out audit

work, many of which relate to the behavioural aspects of work:

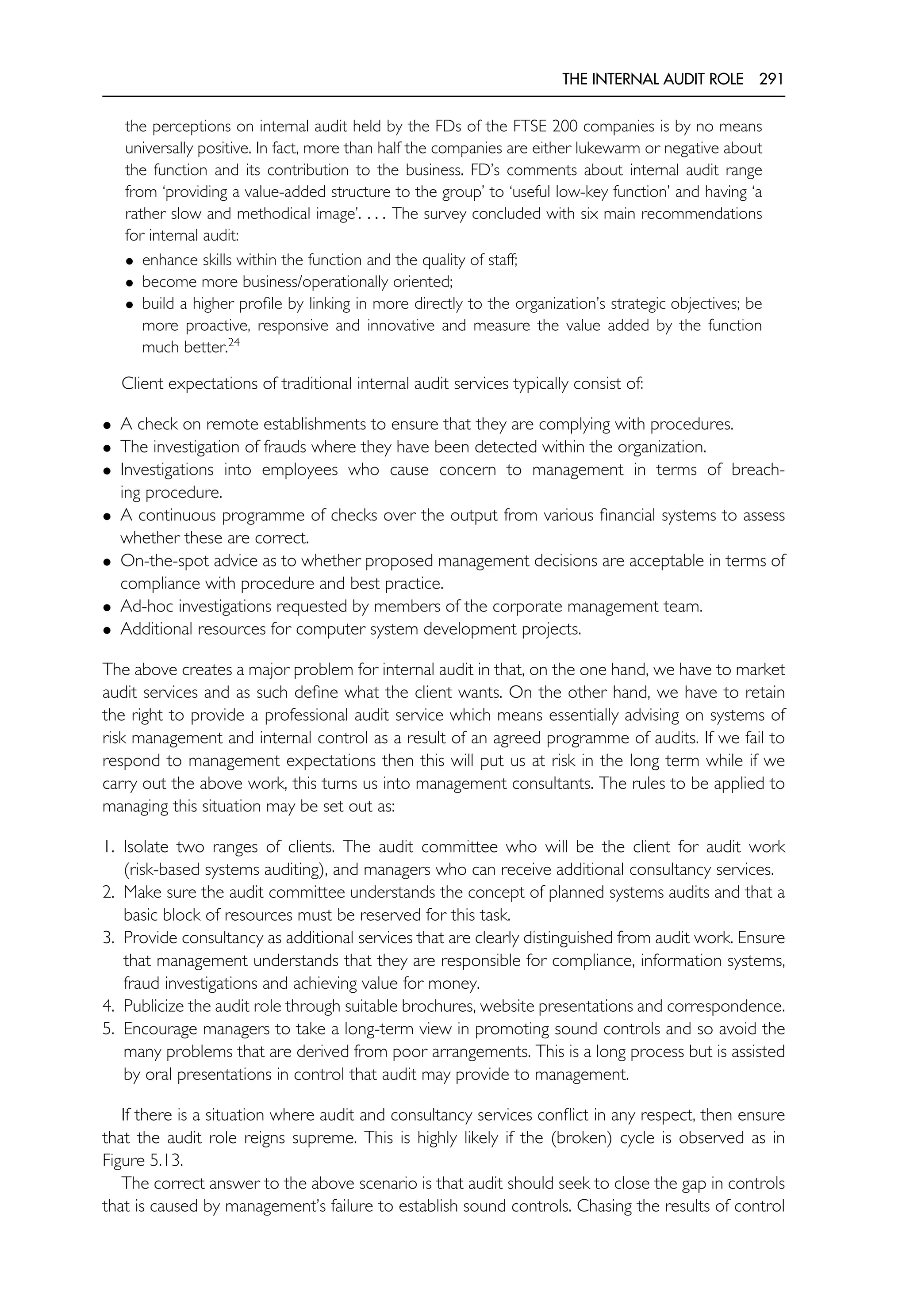

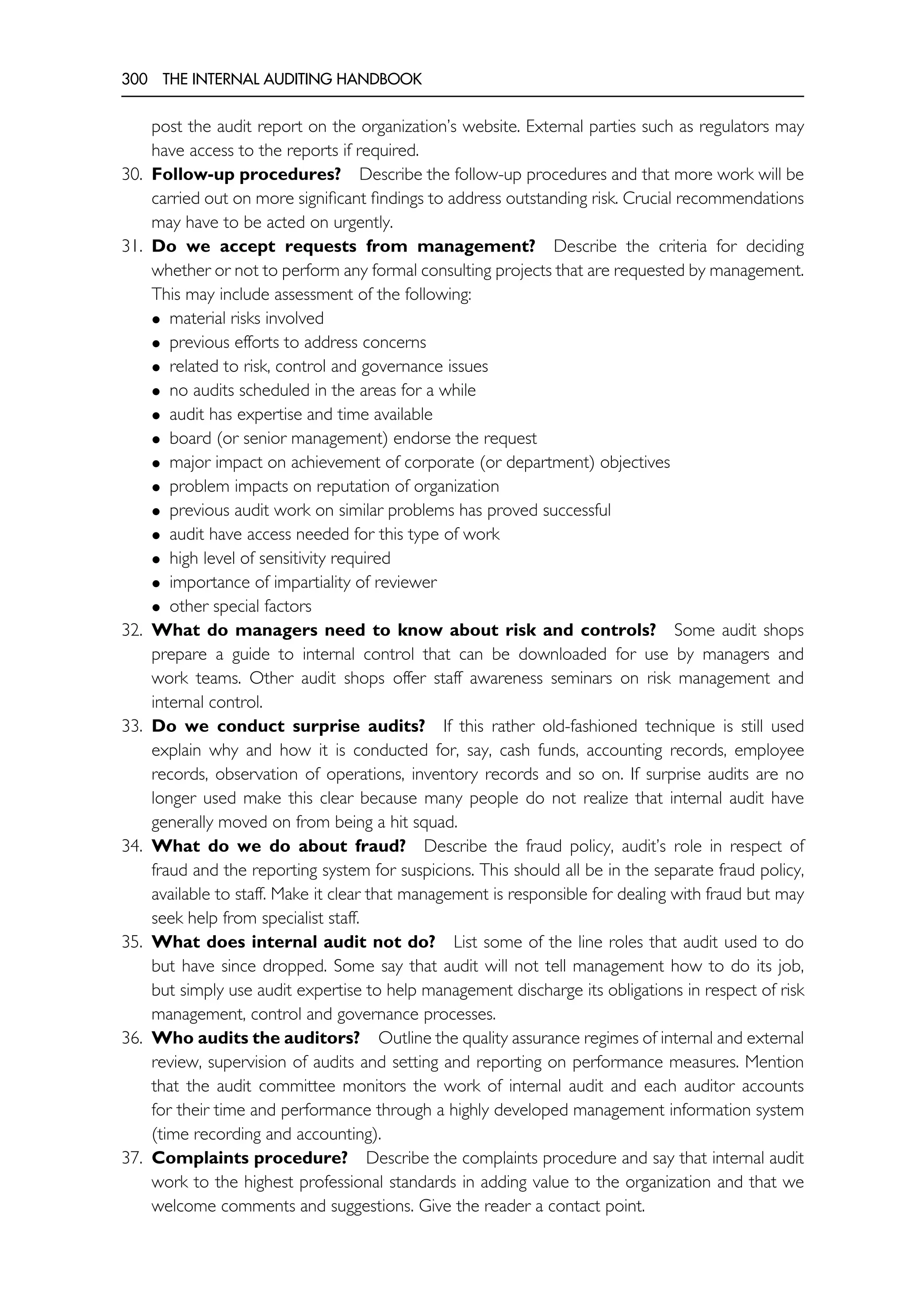

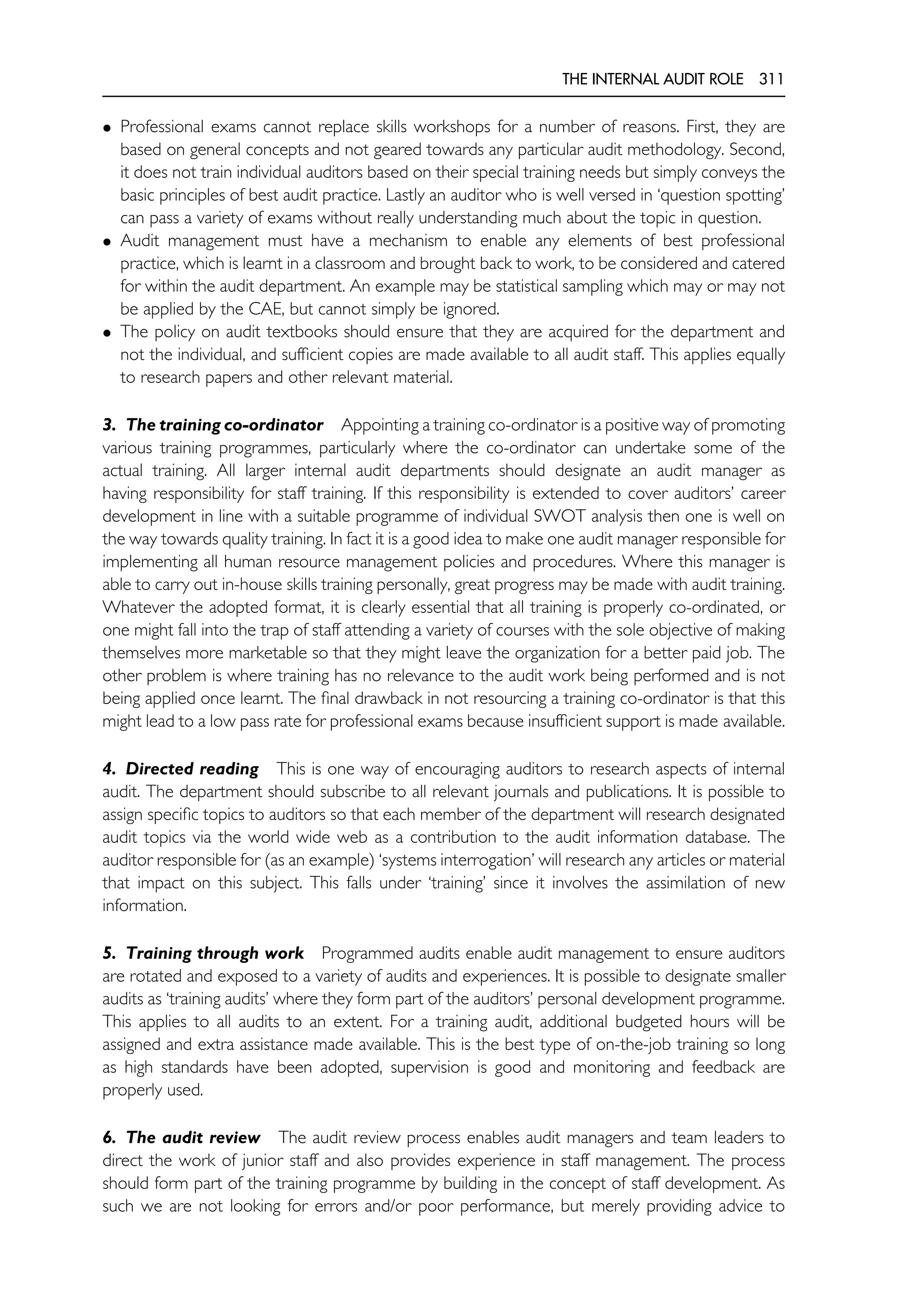

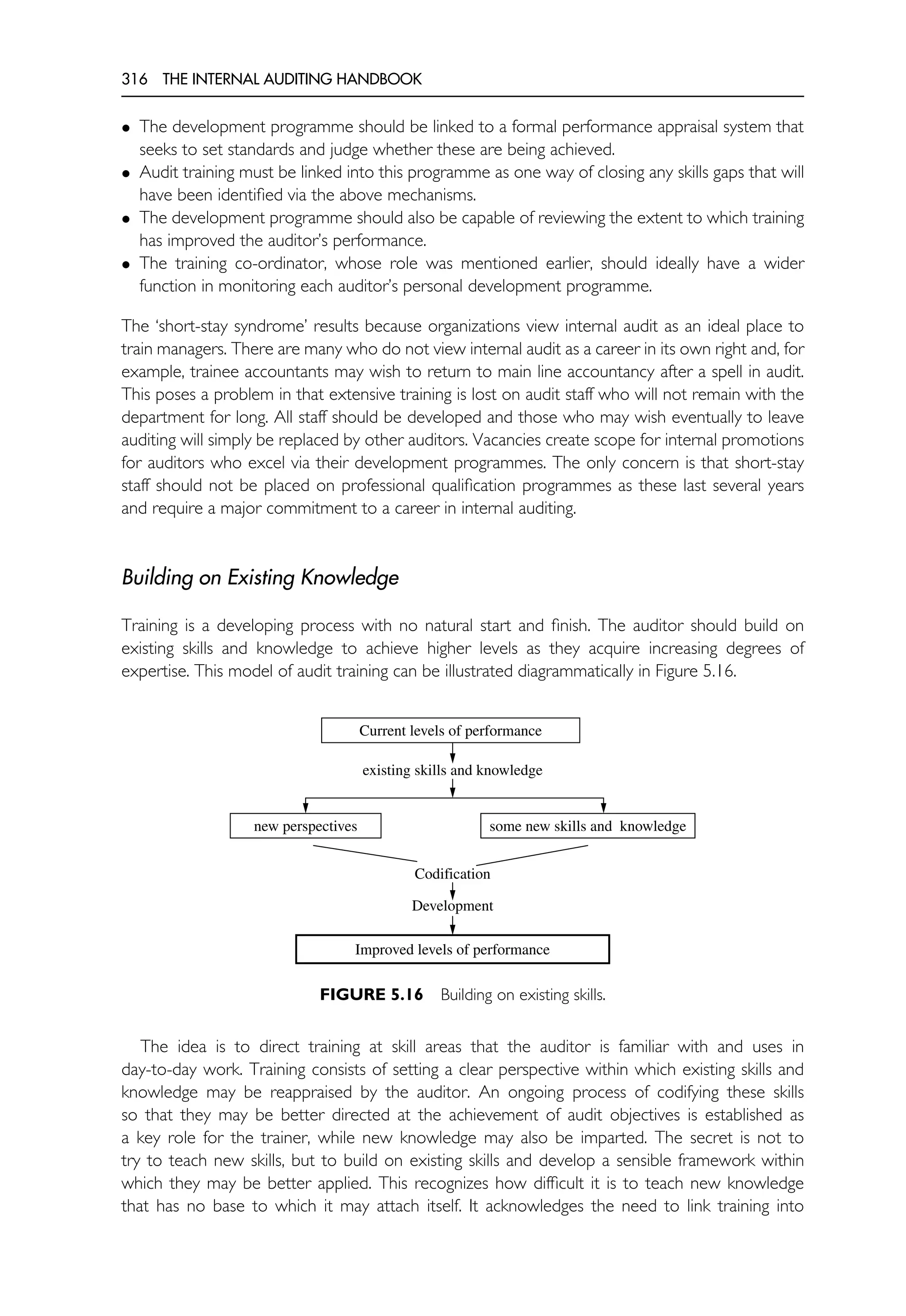

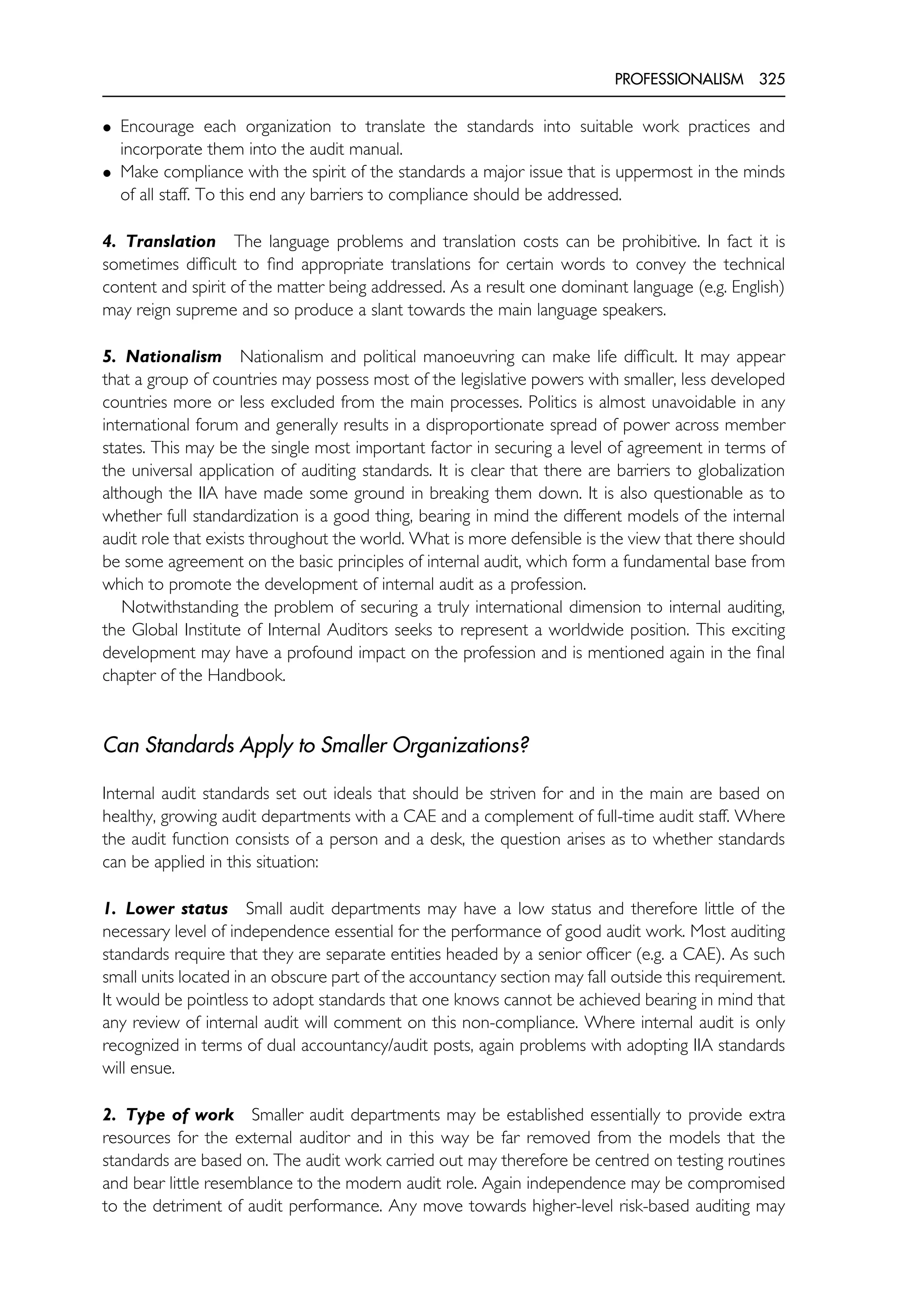

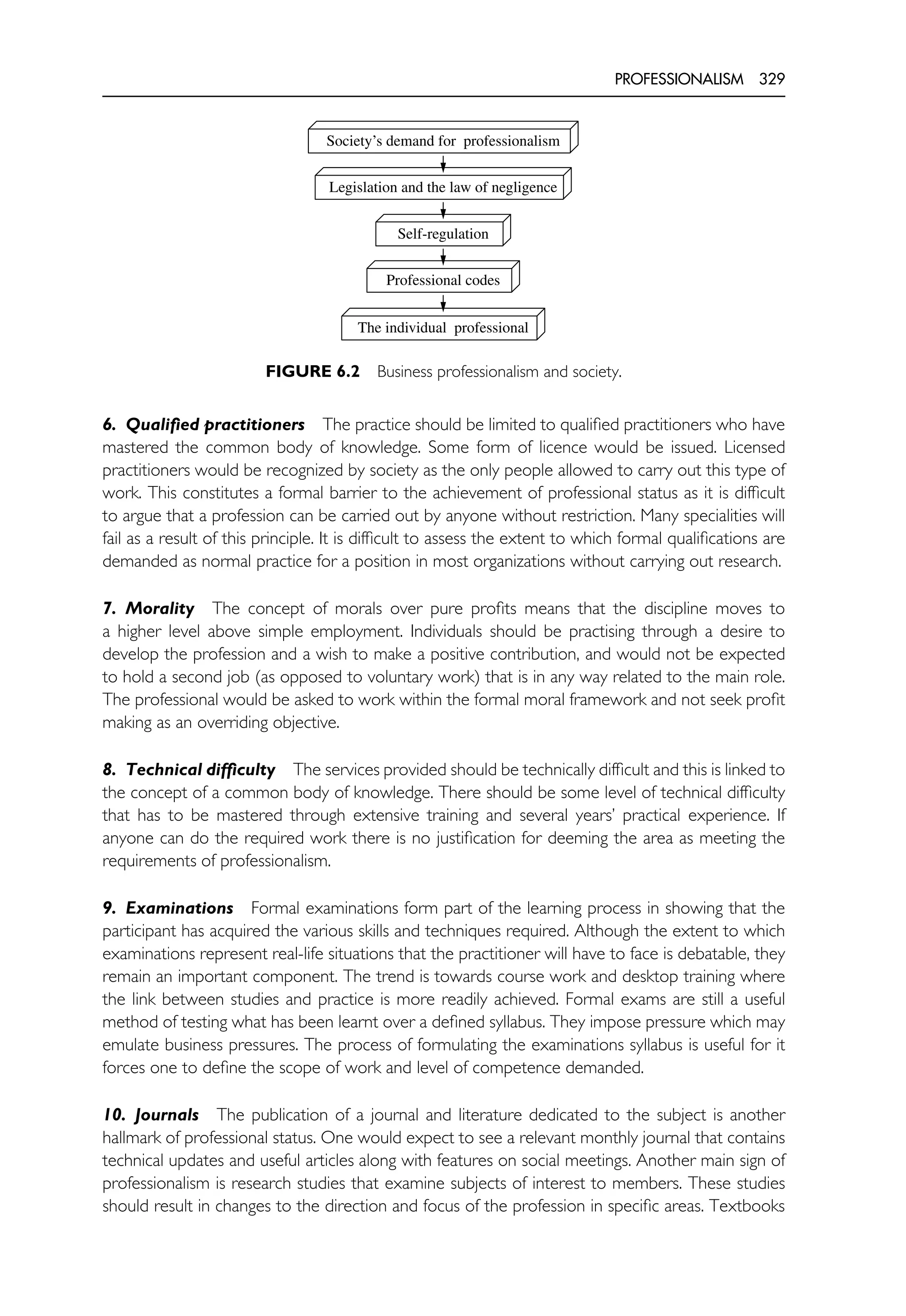

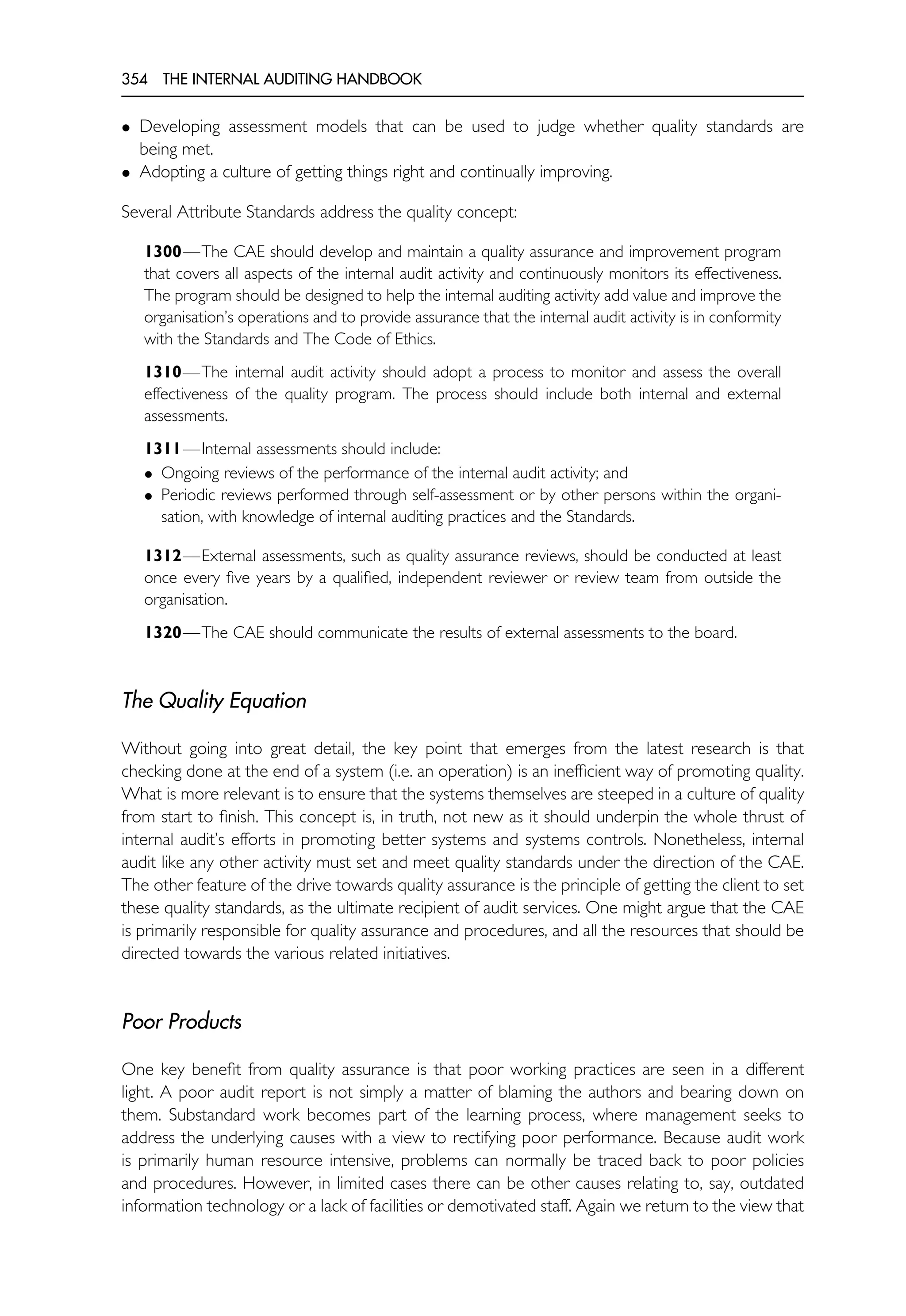

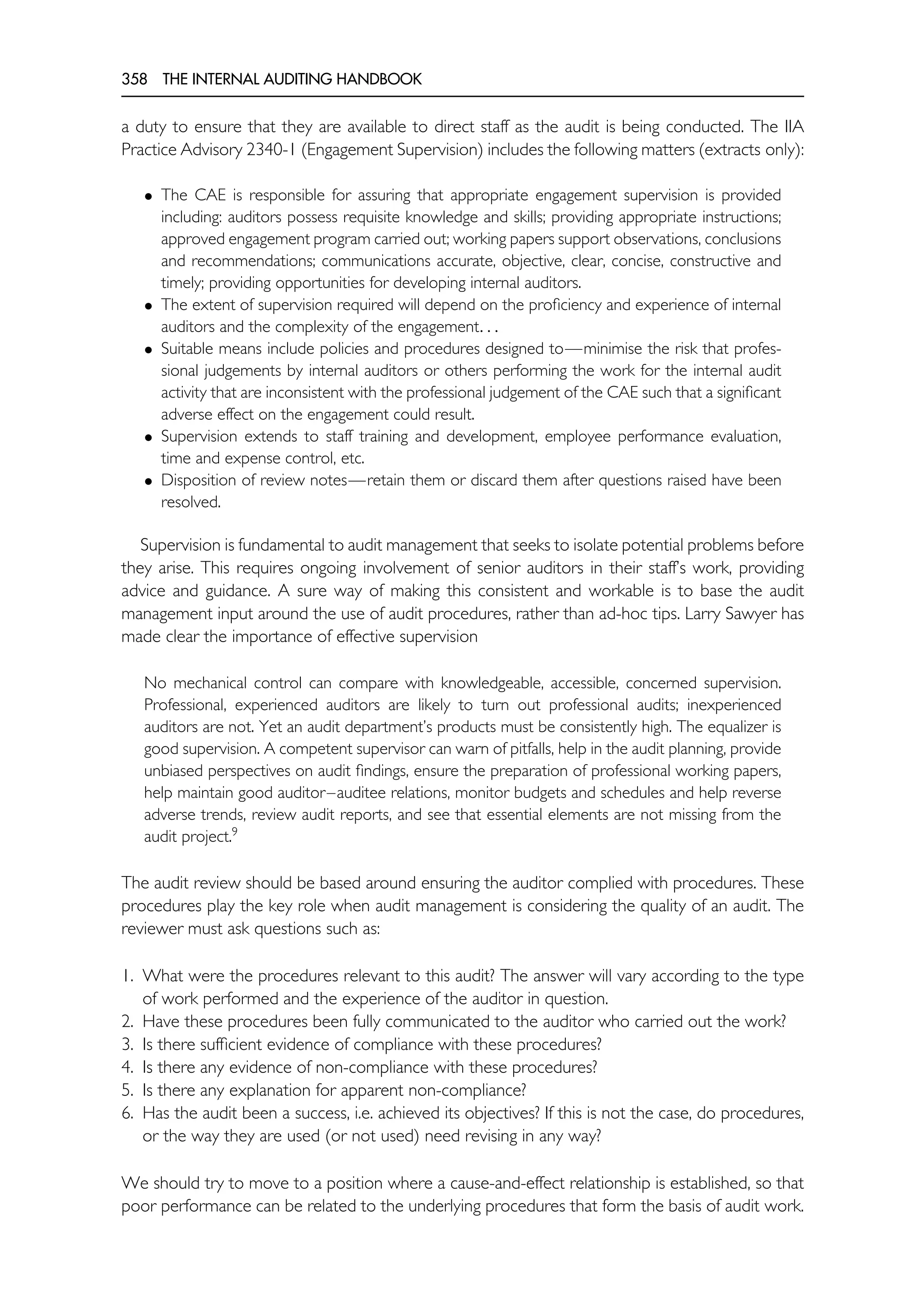

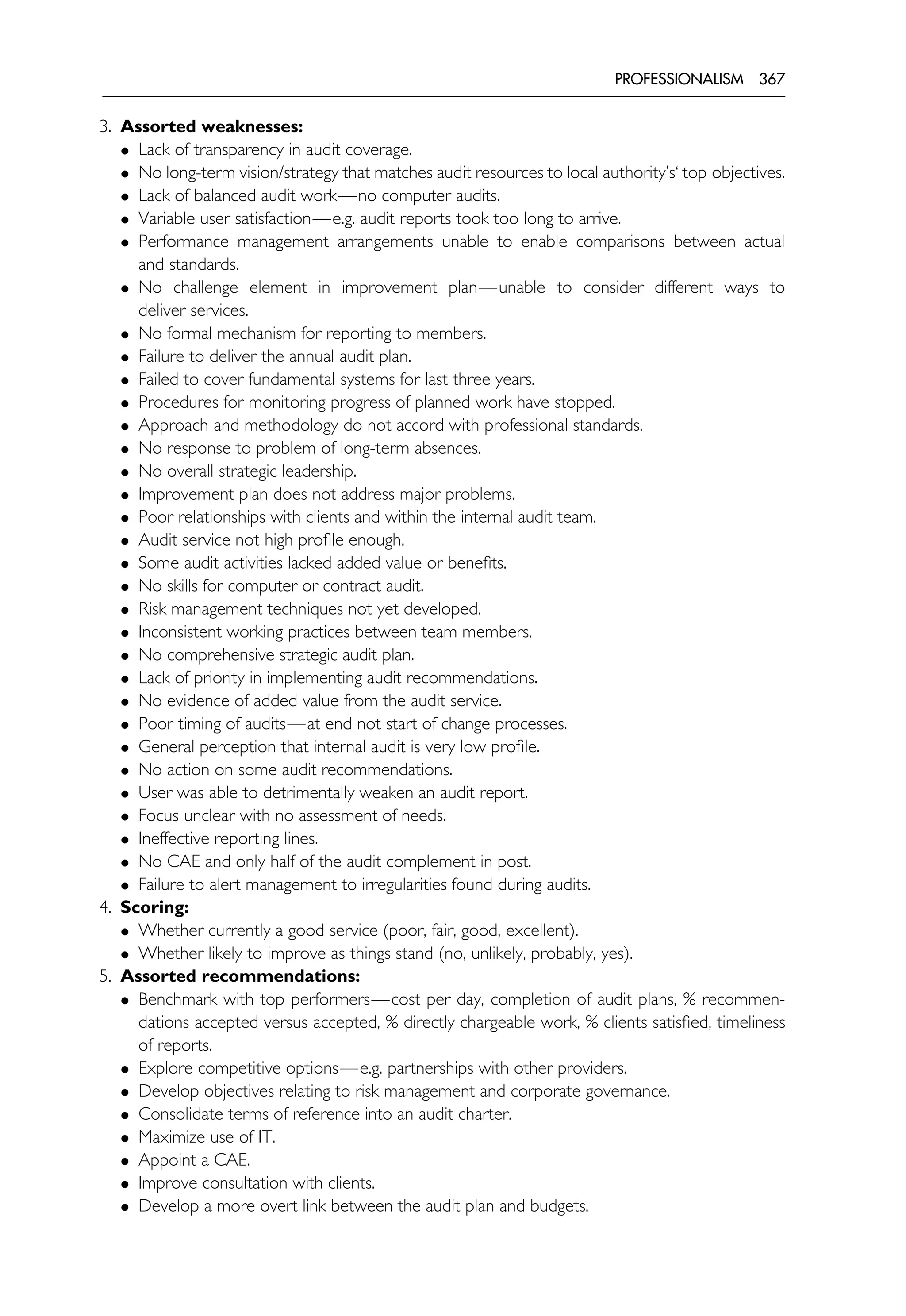

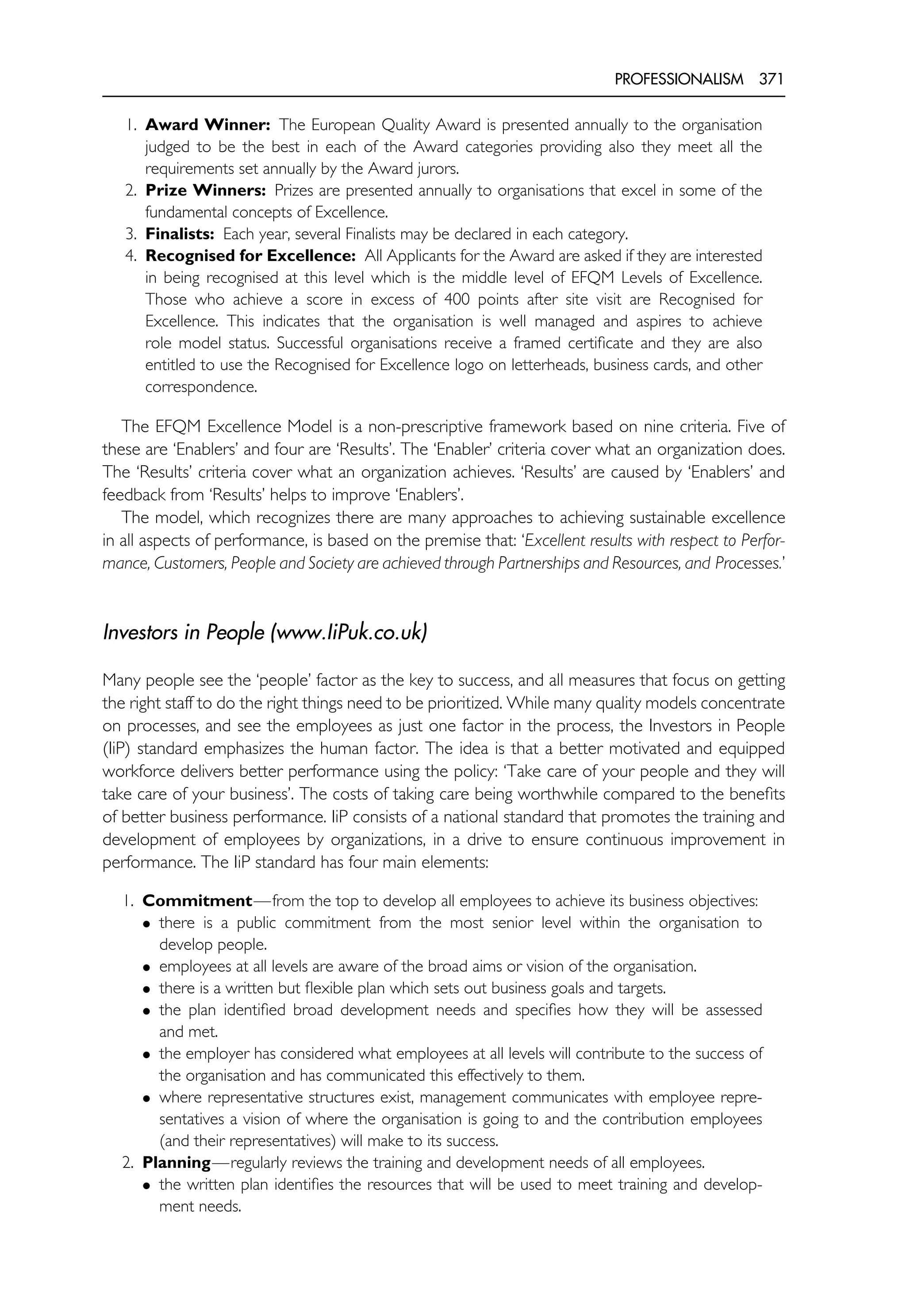

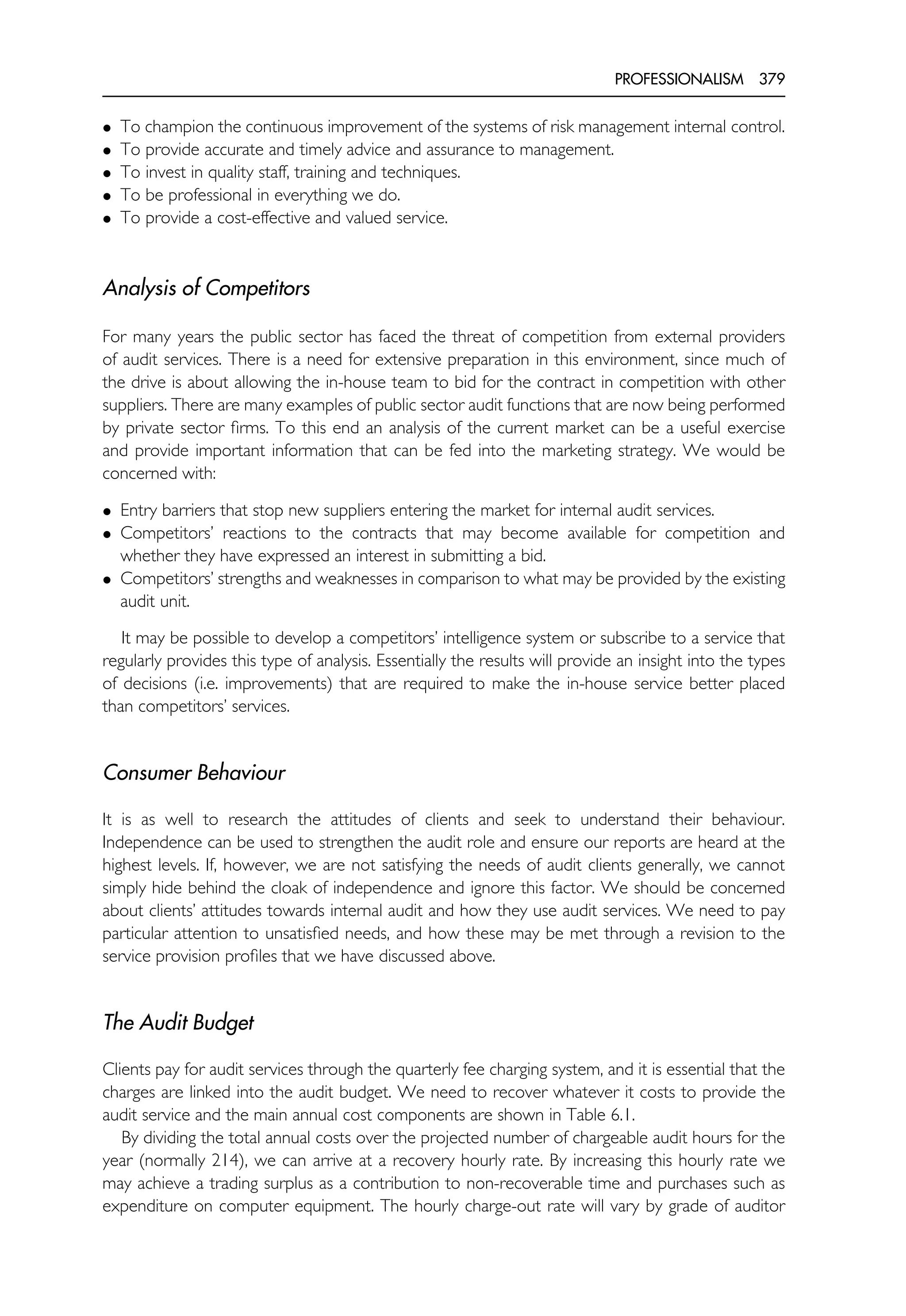

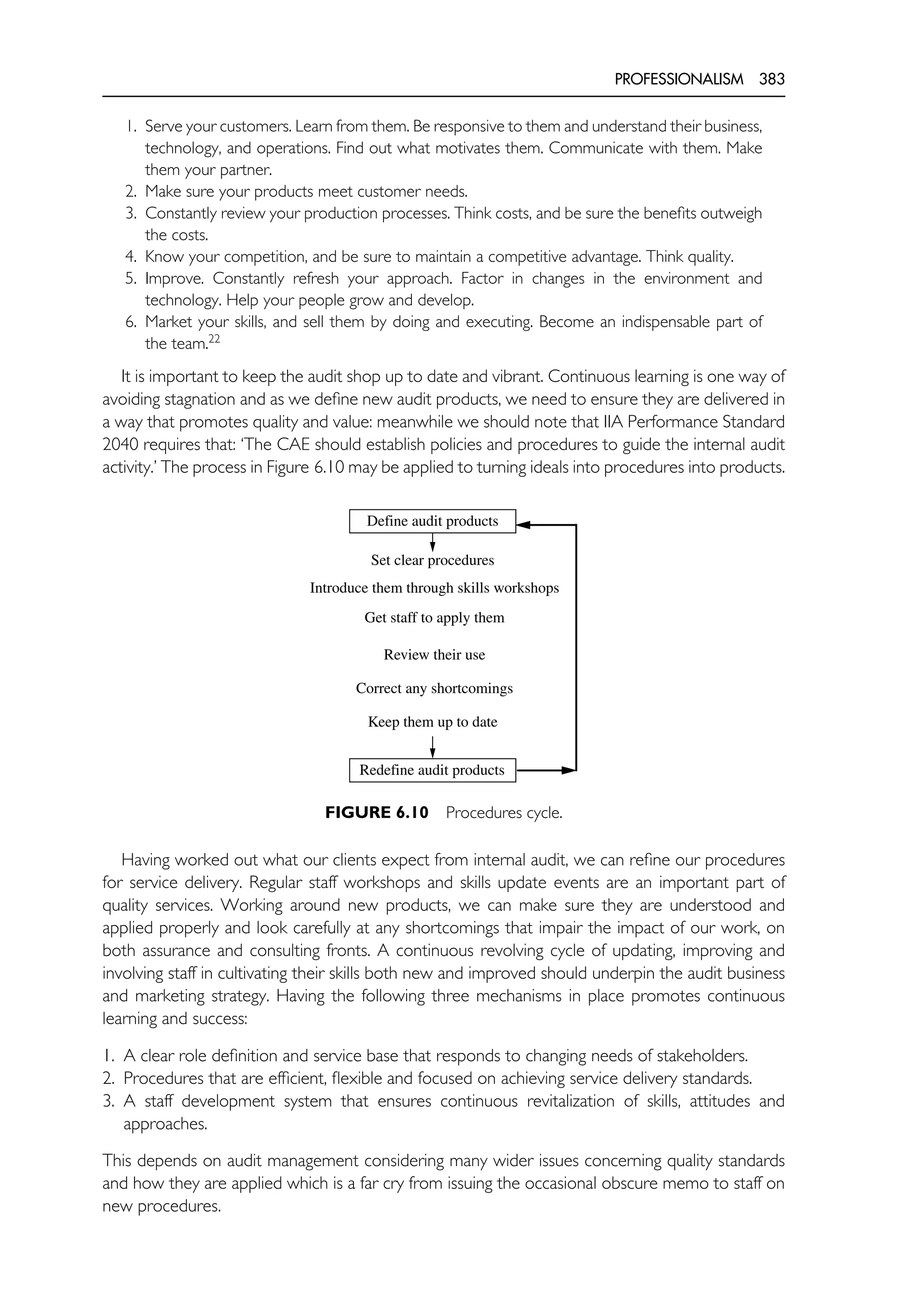

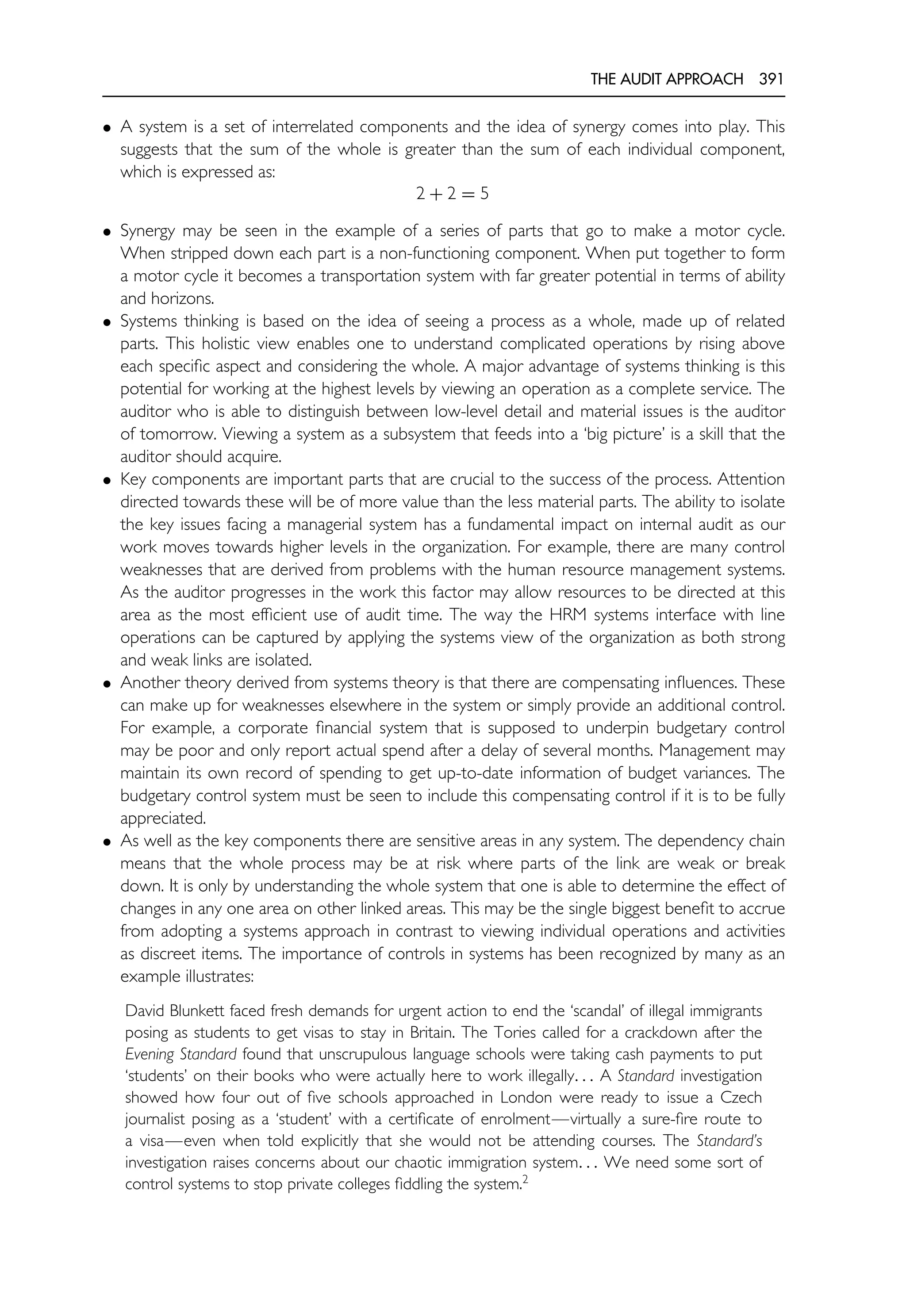

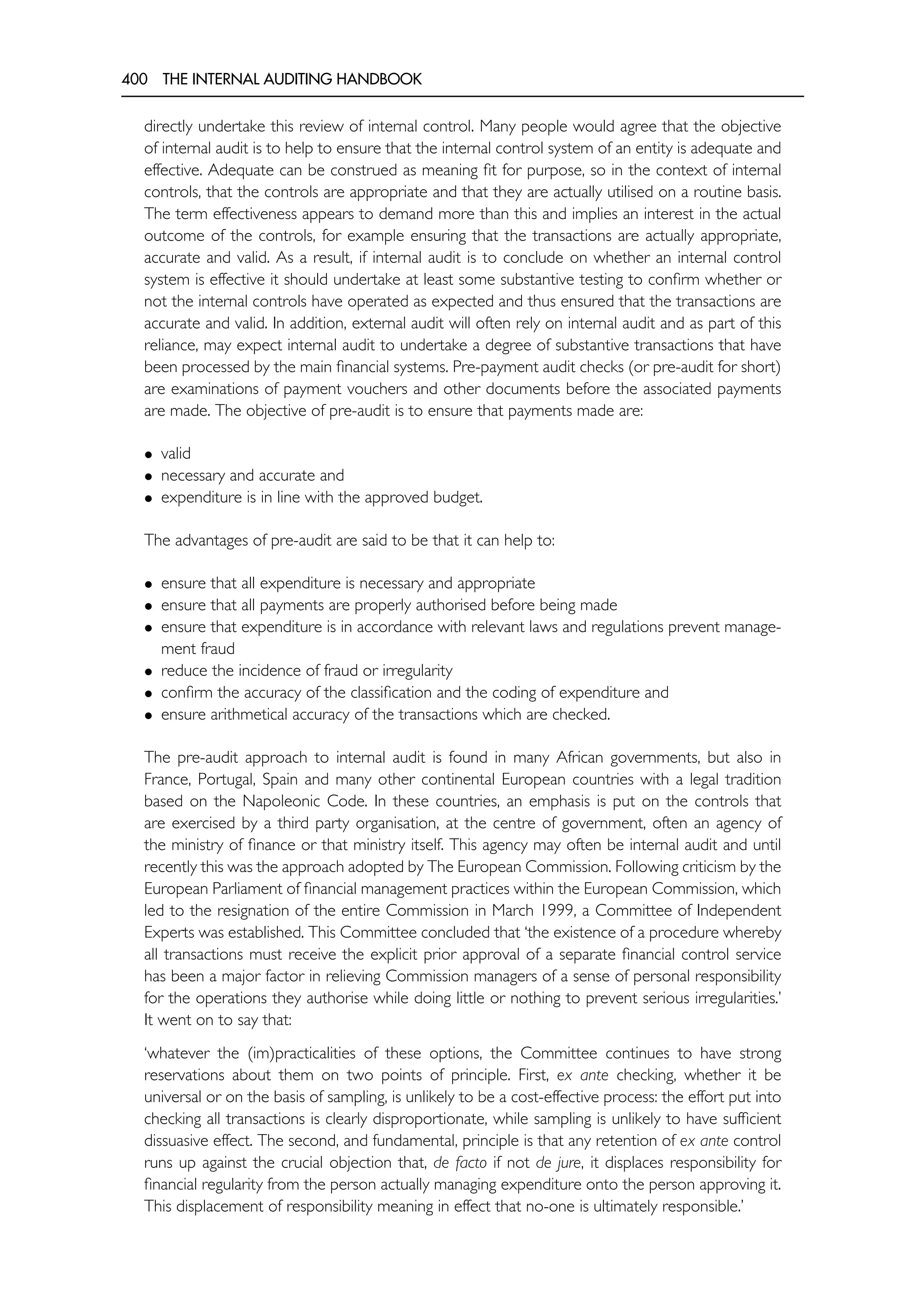

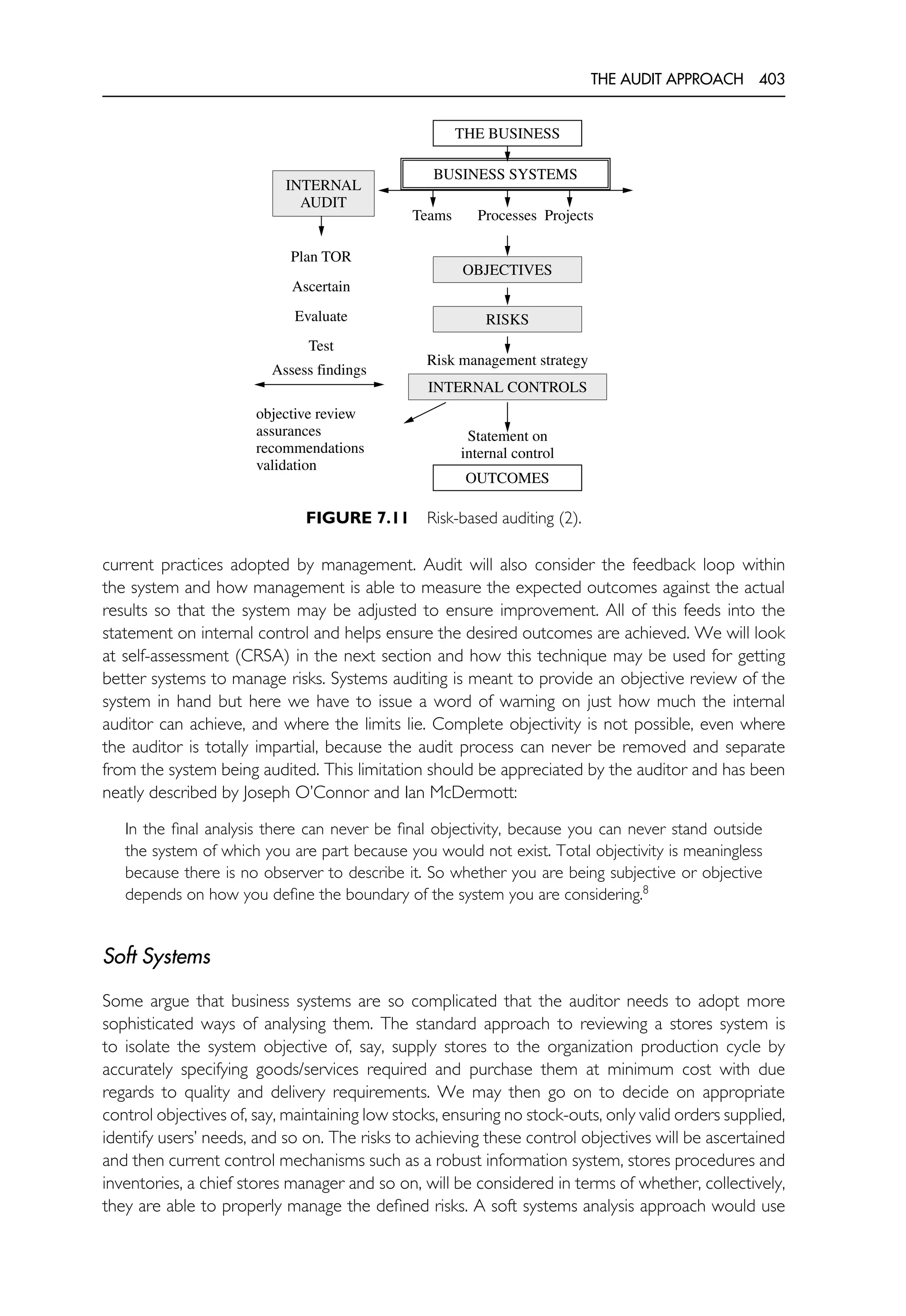

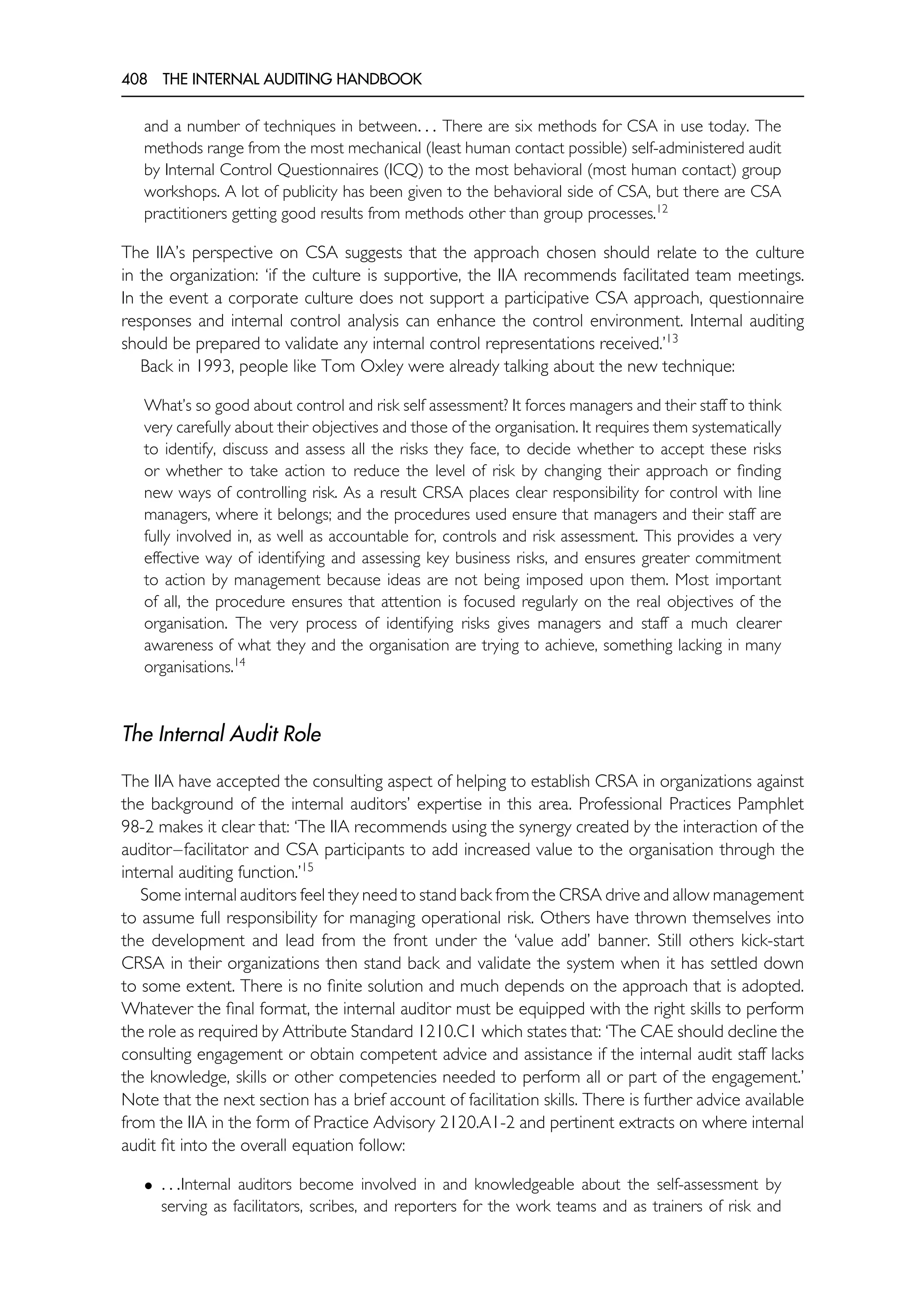

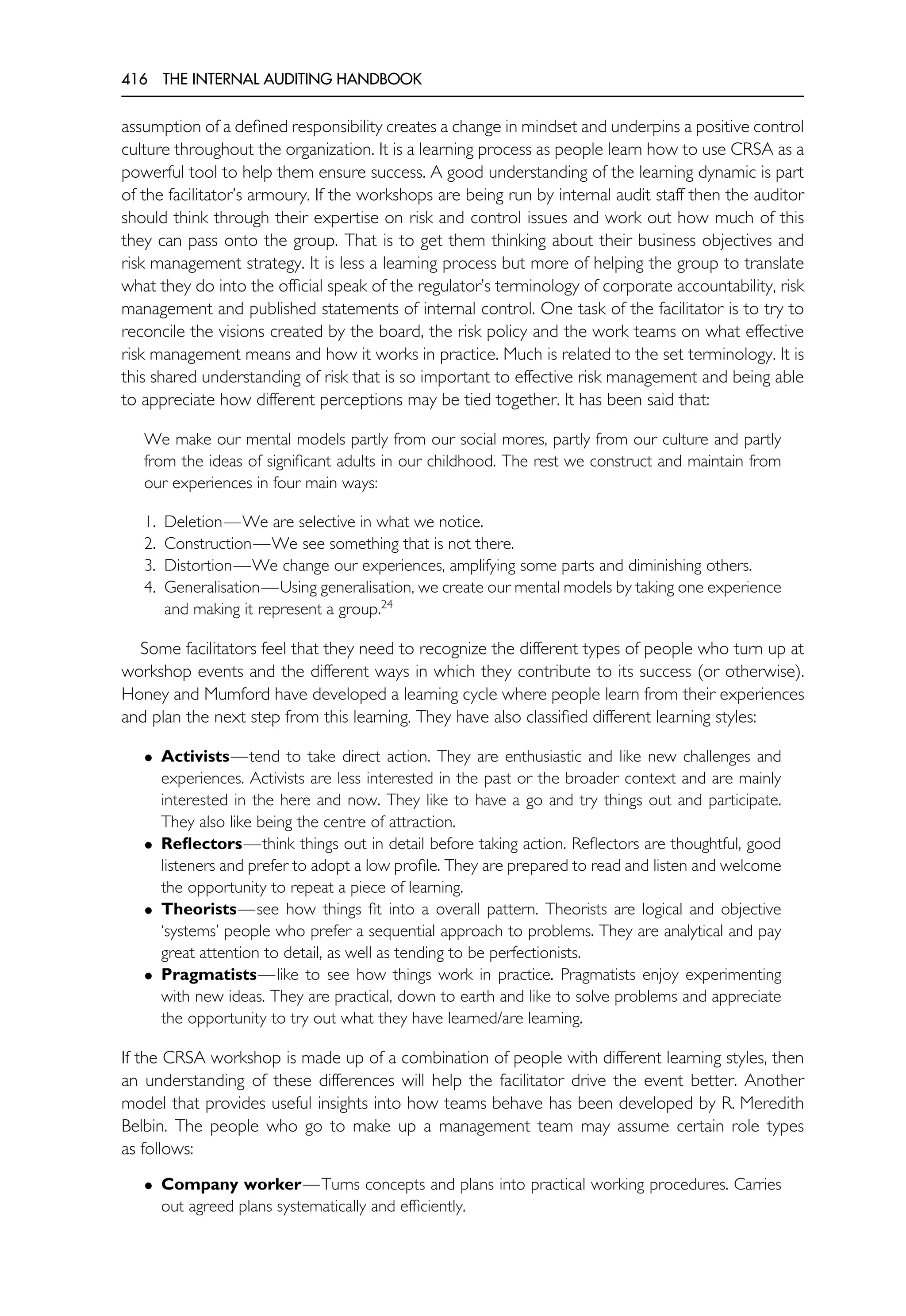

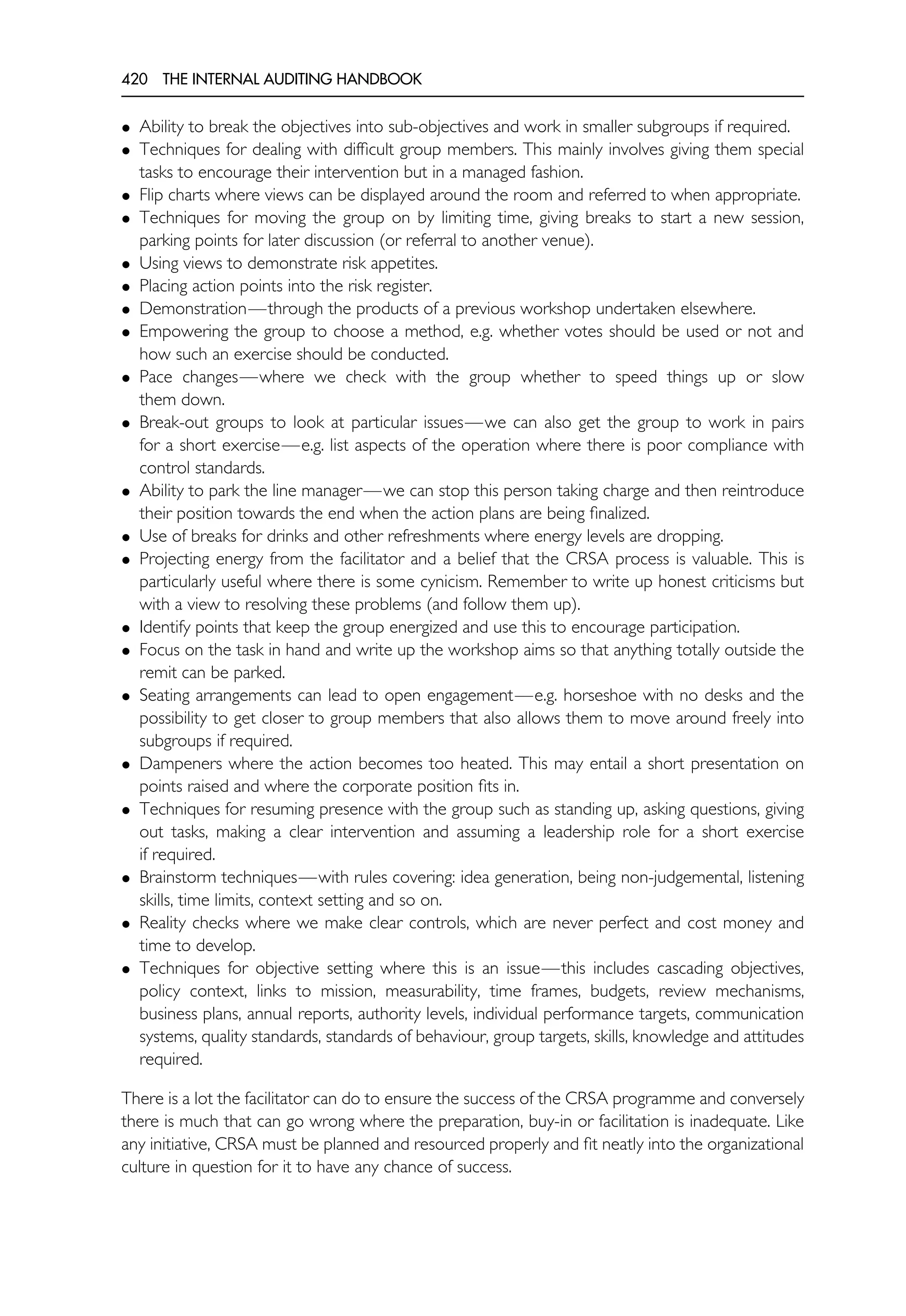

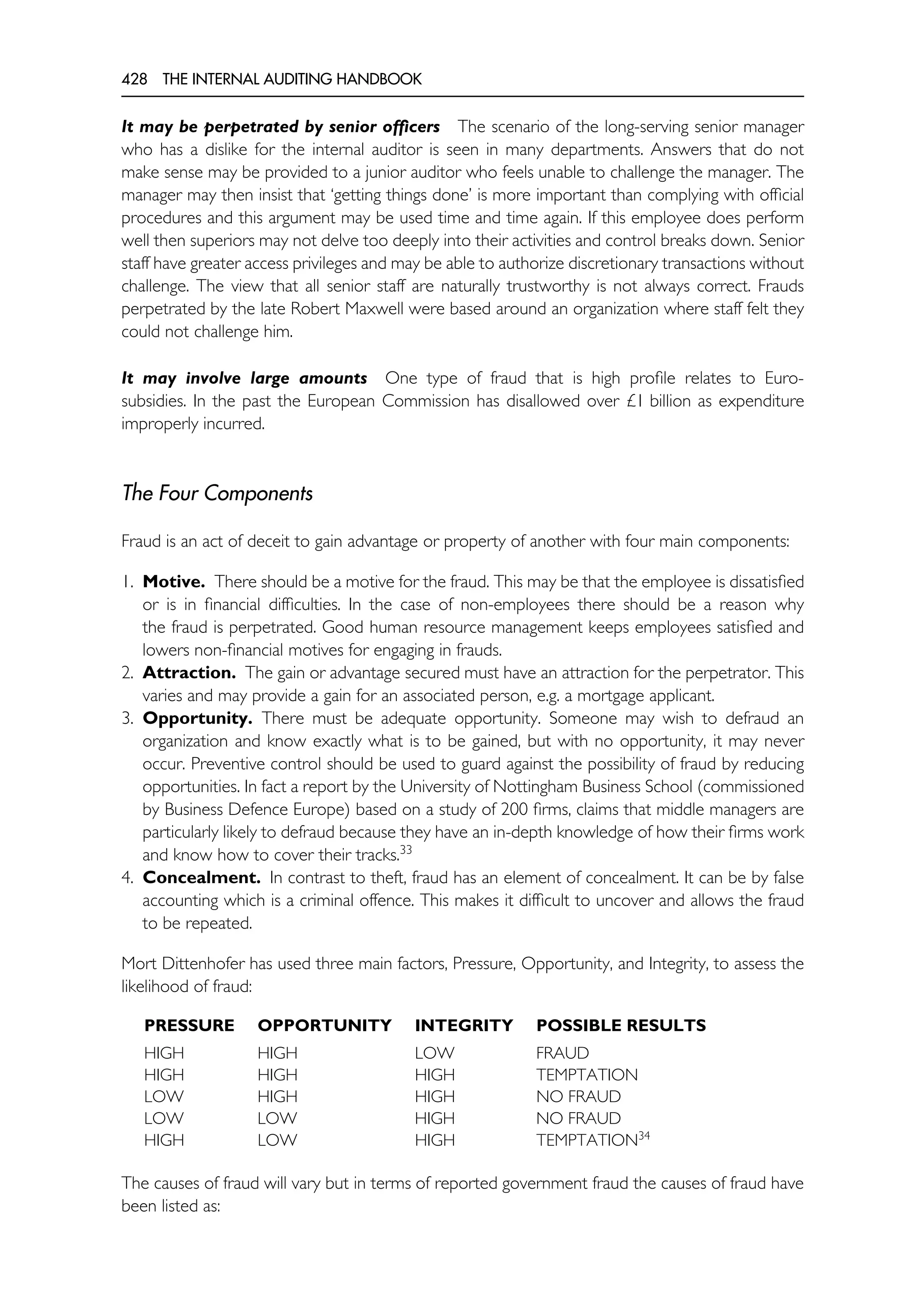

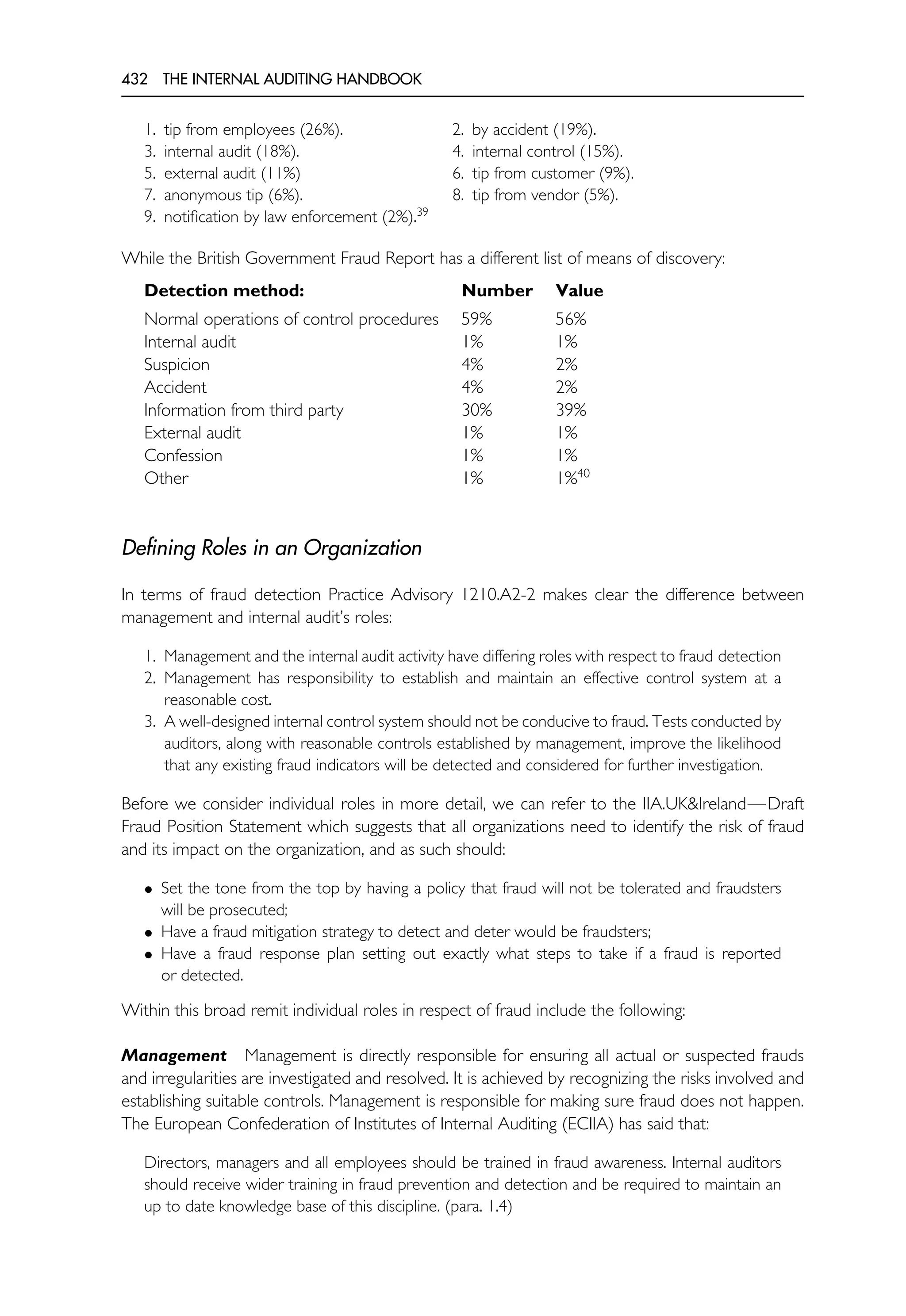

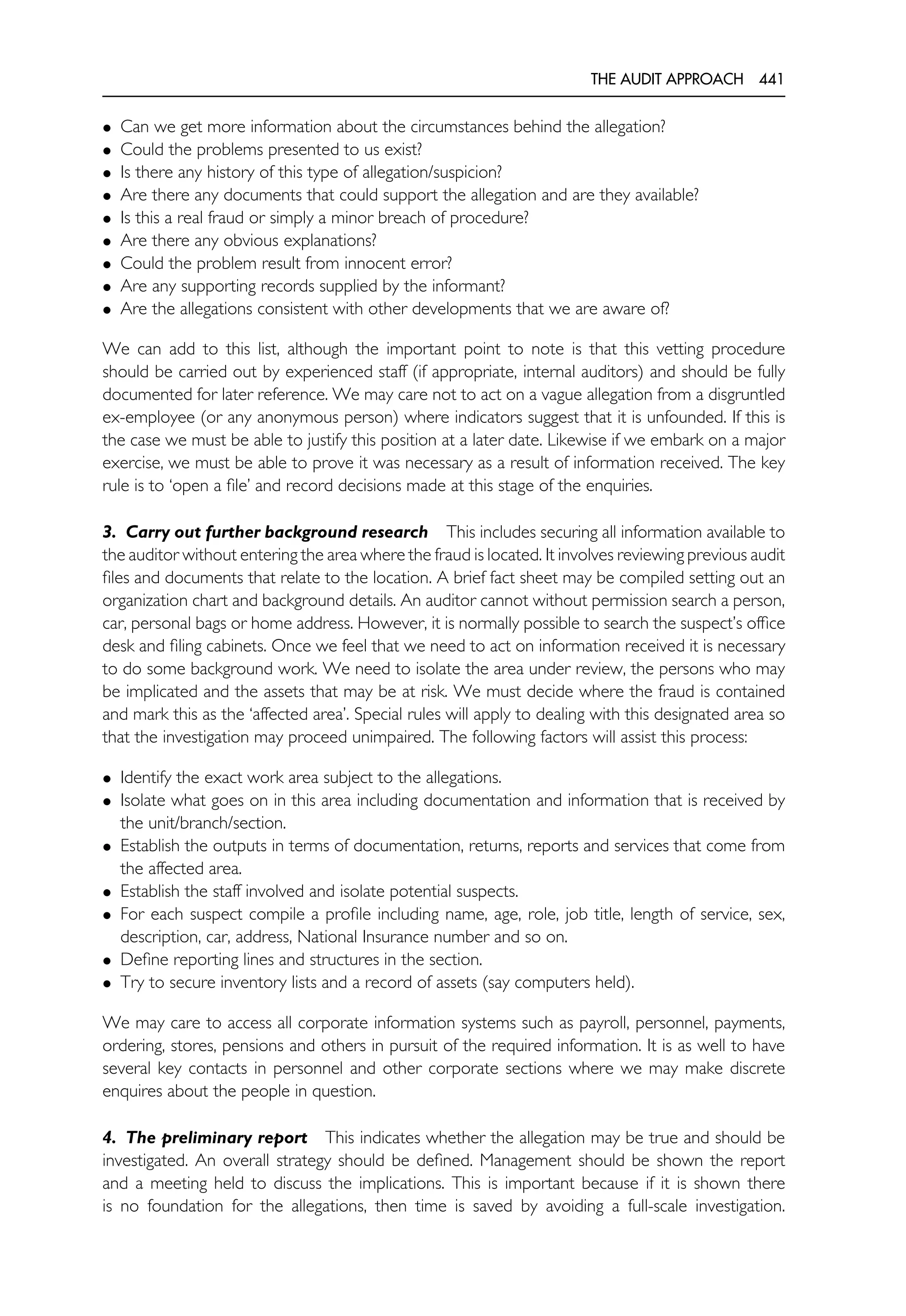

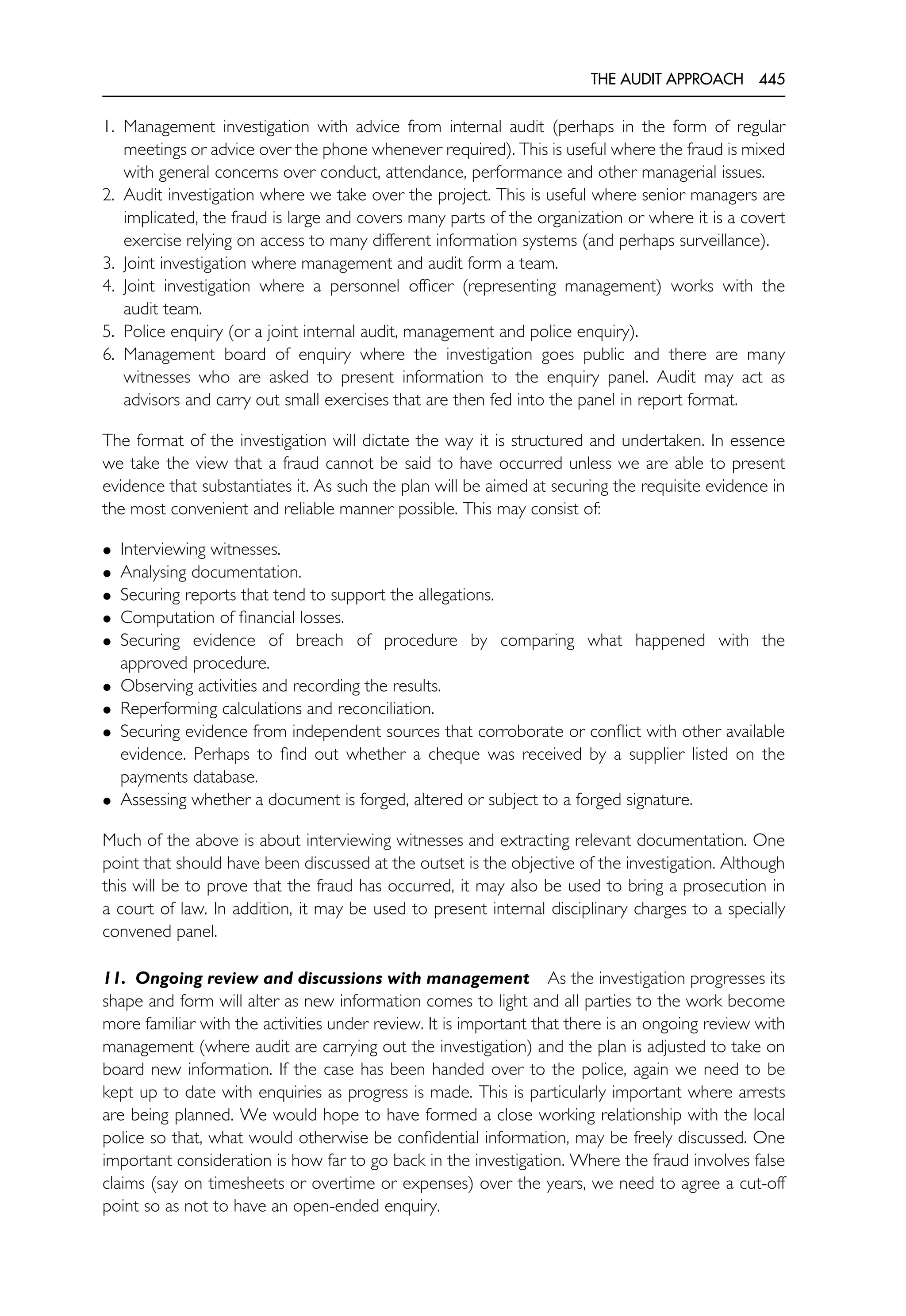

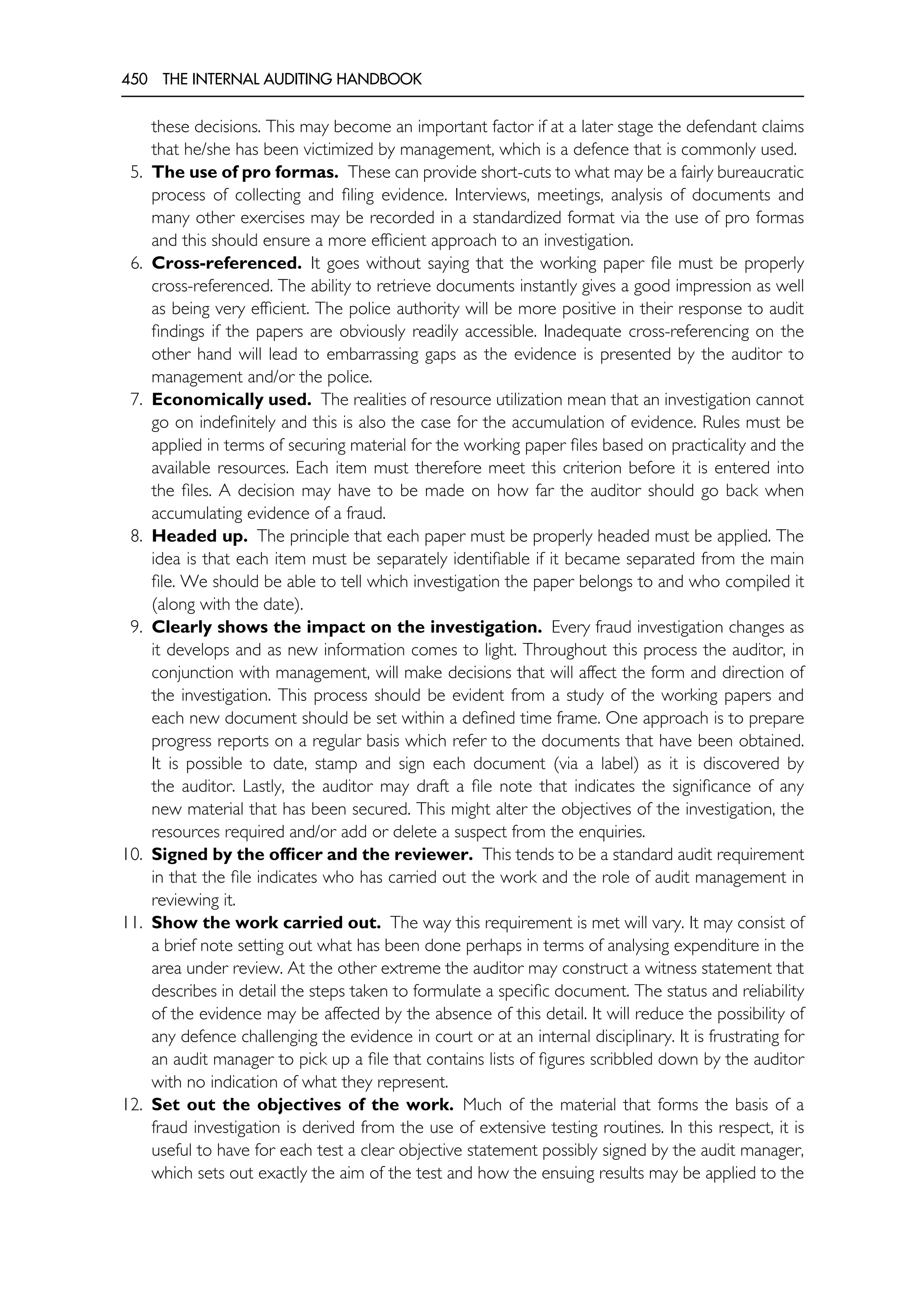

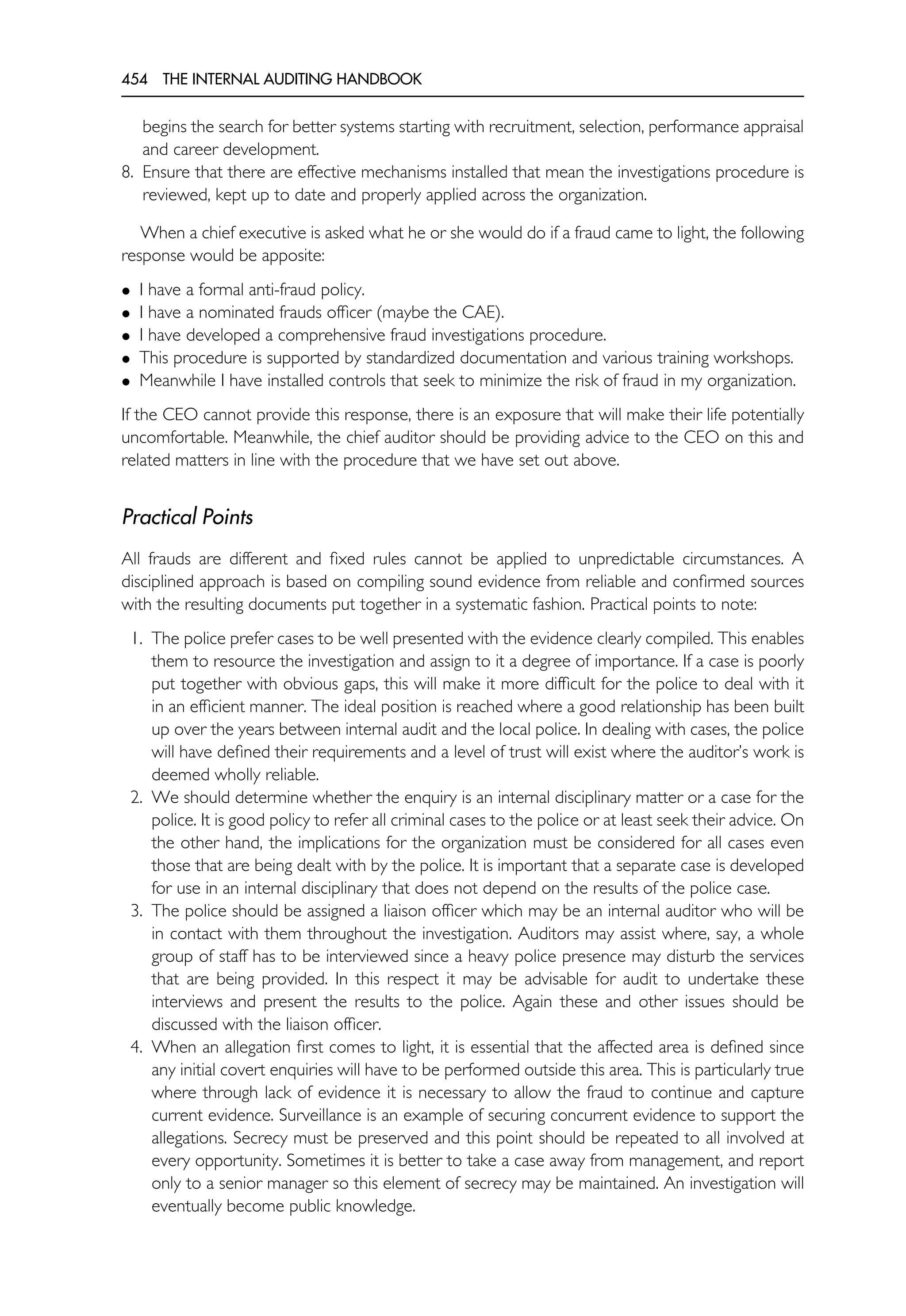

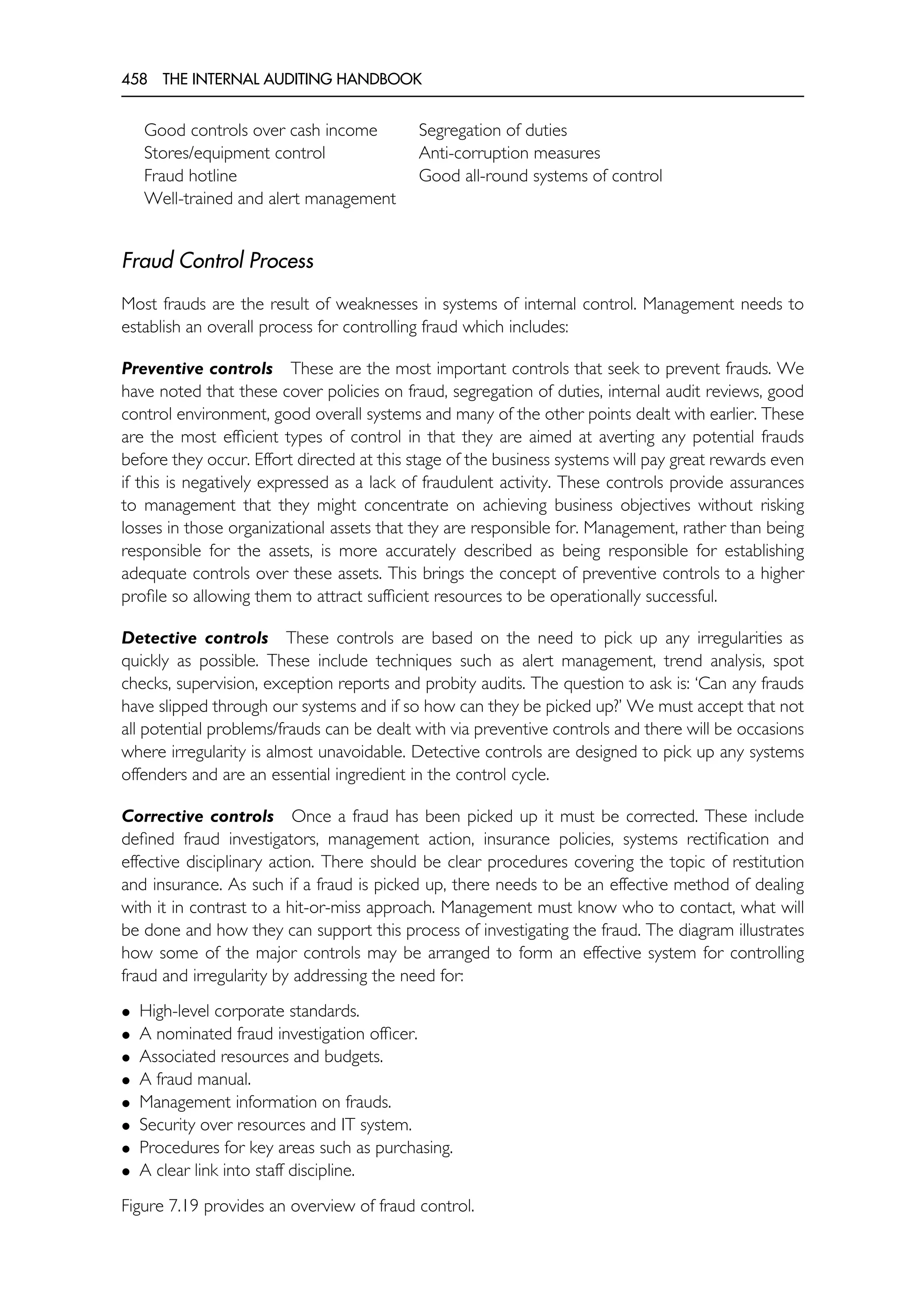

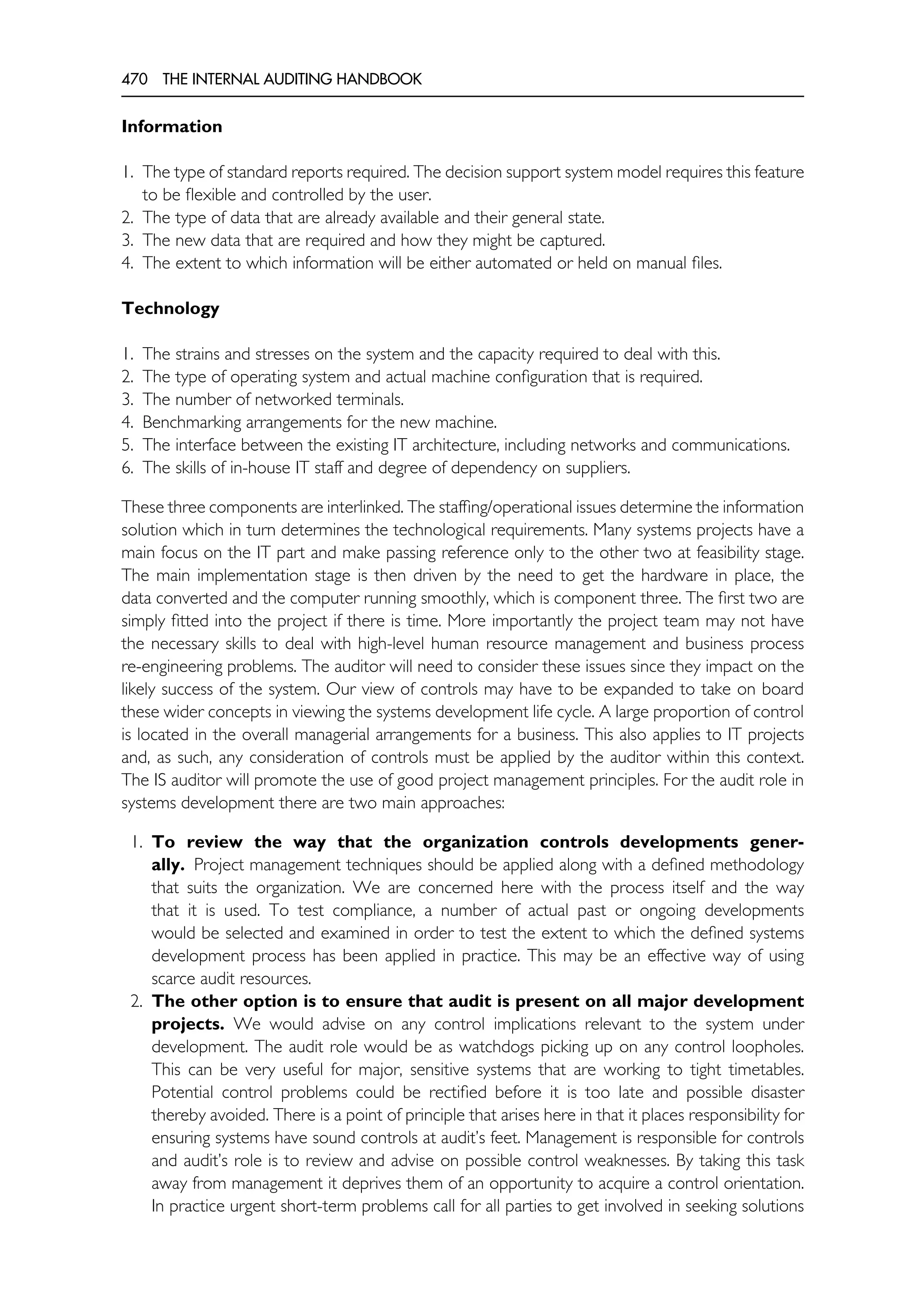

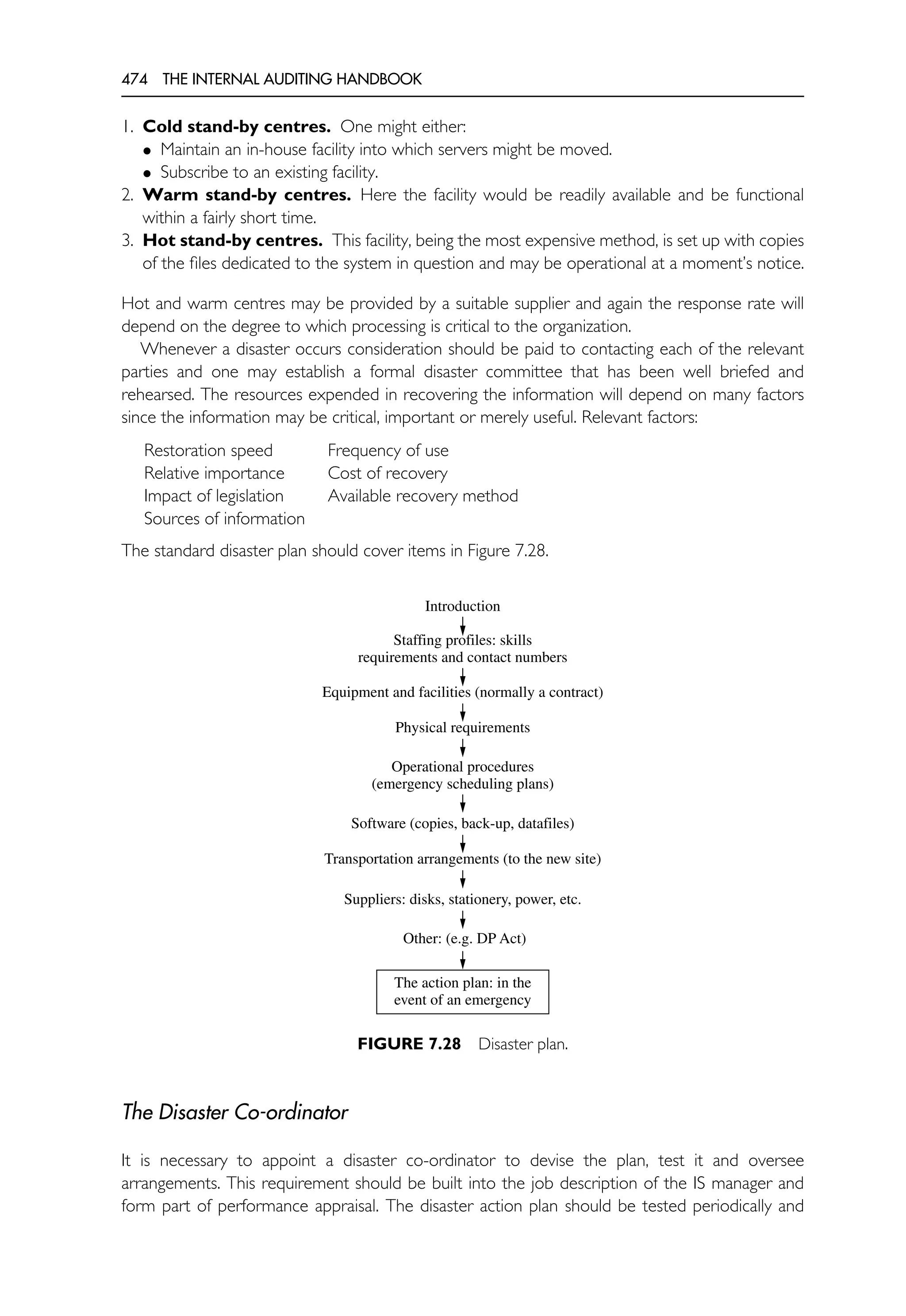

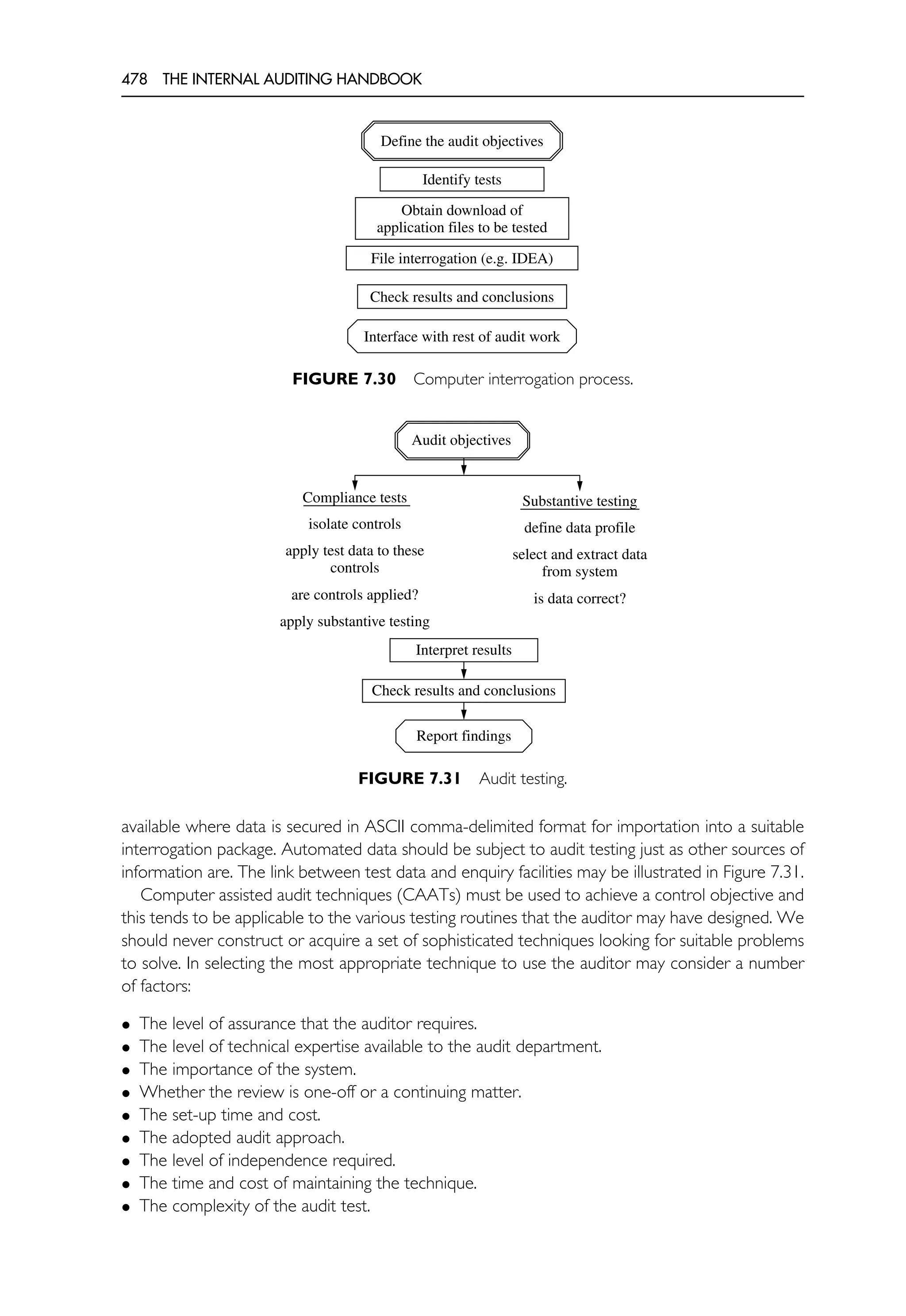

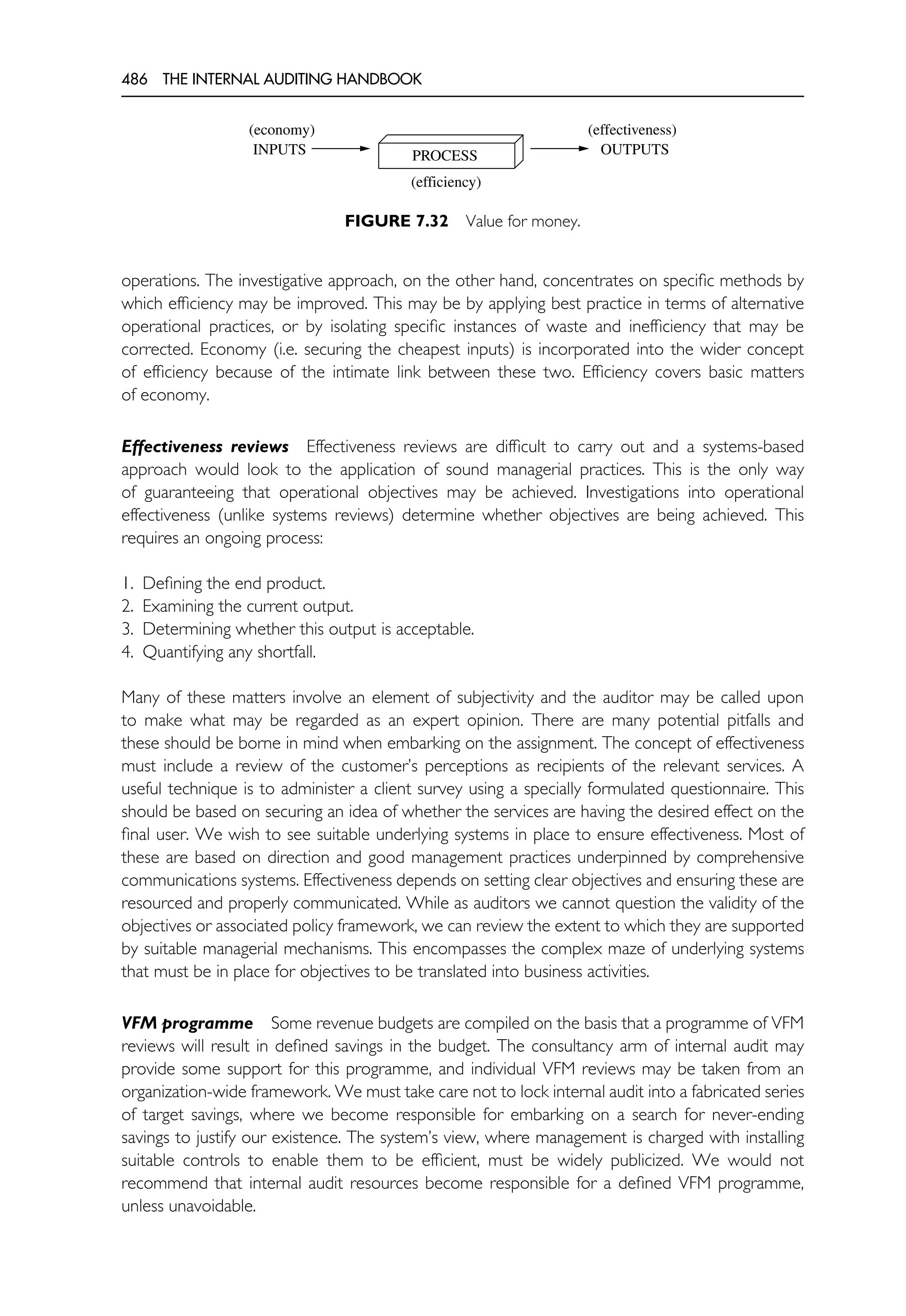

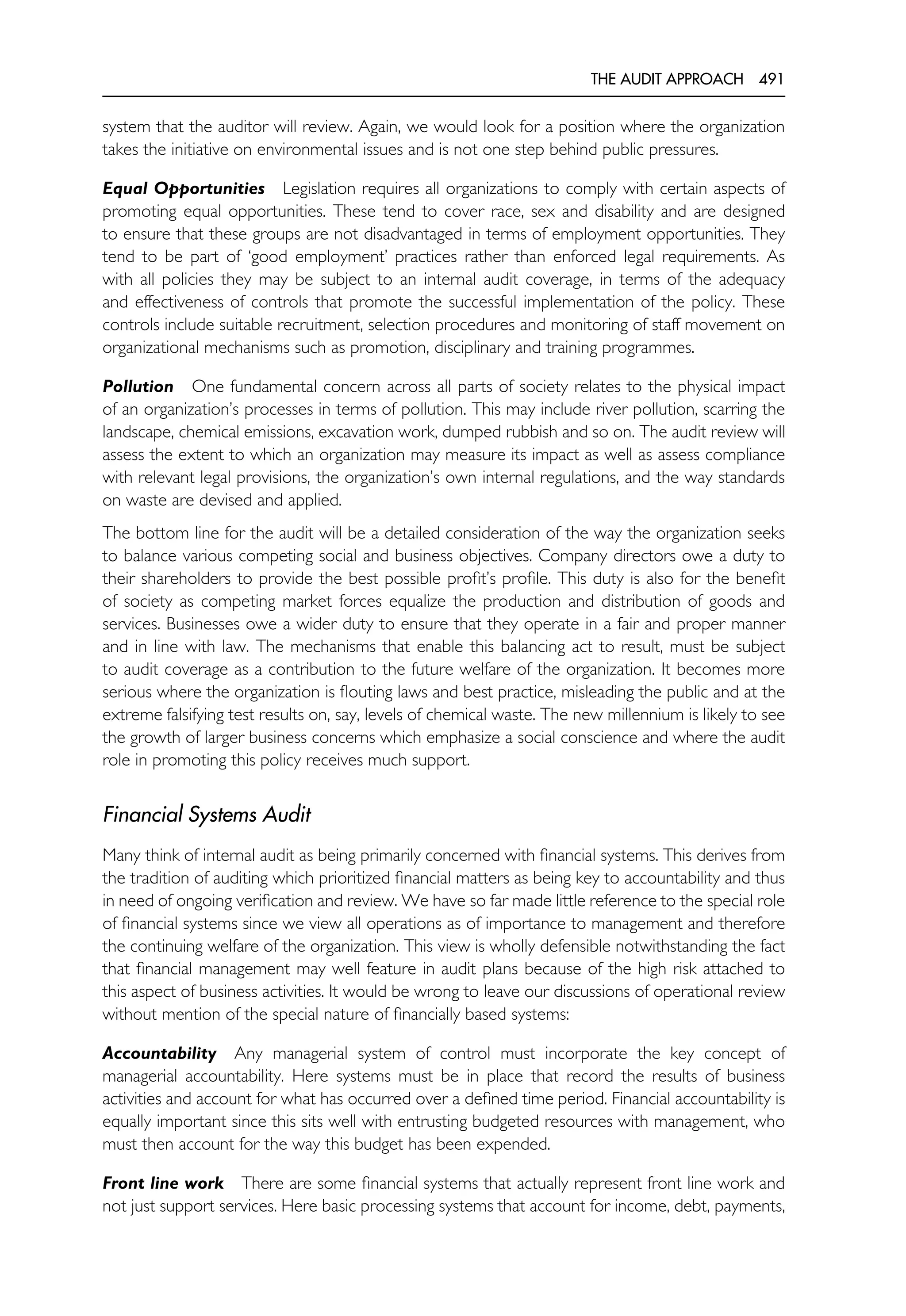

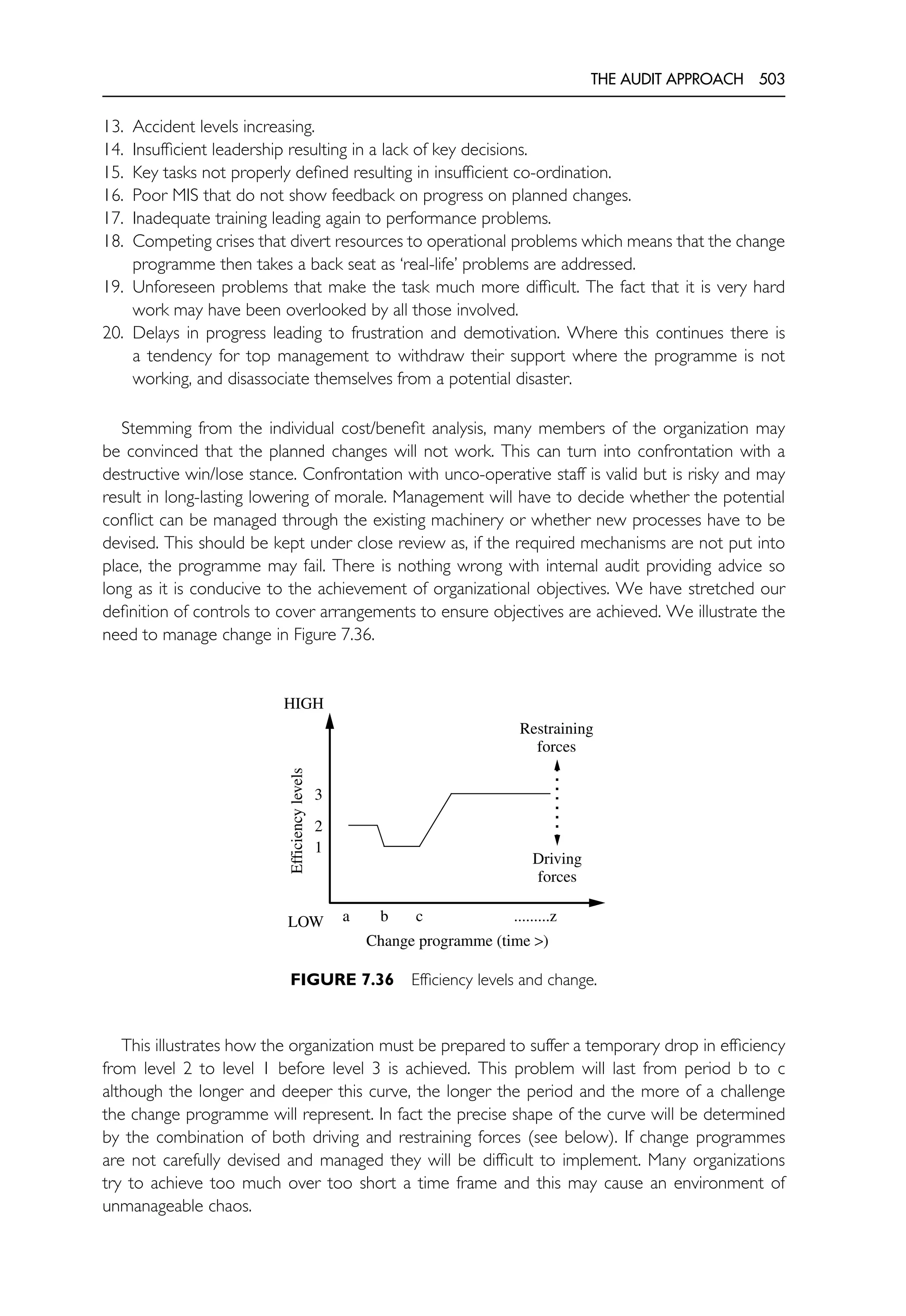

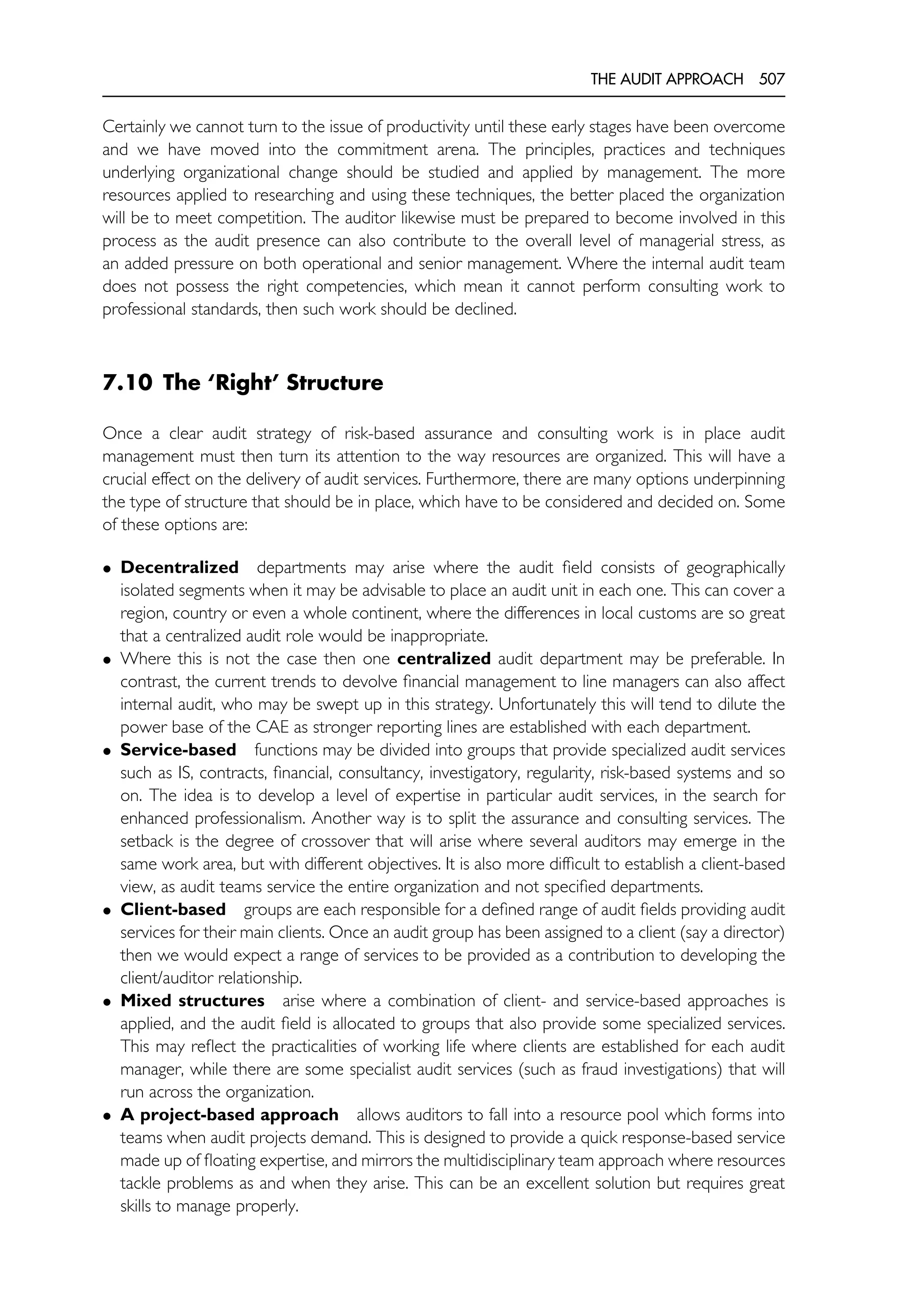

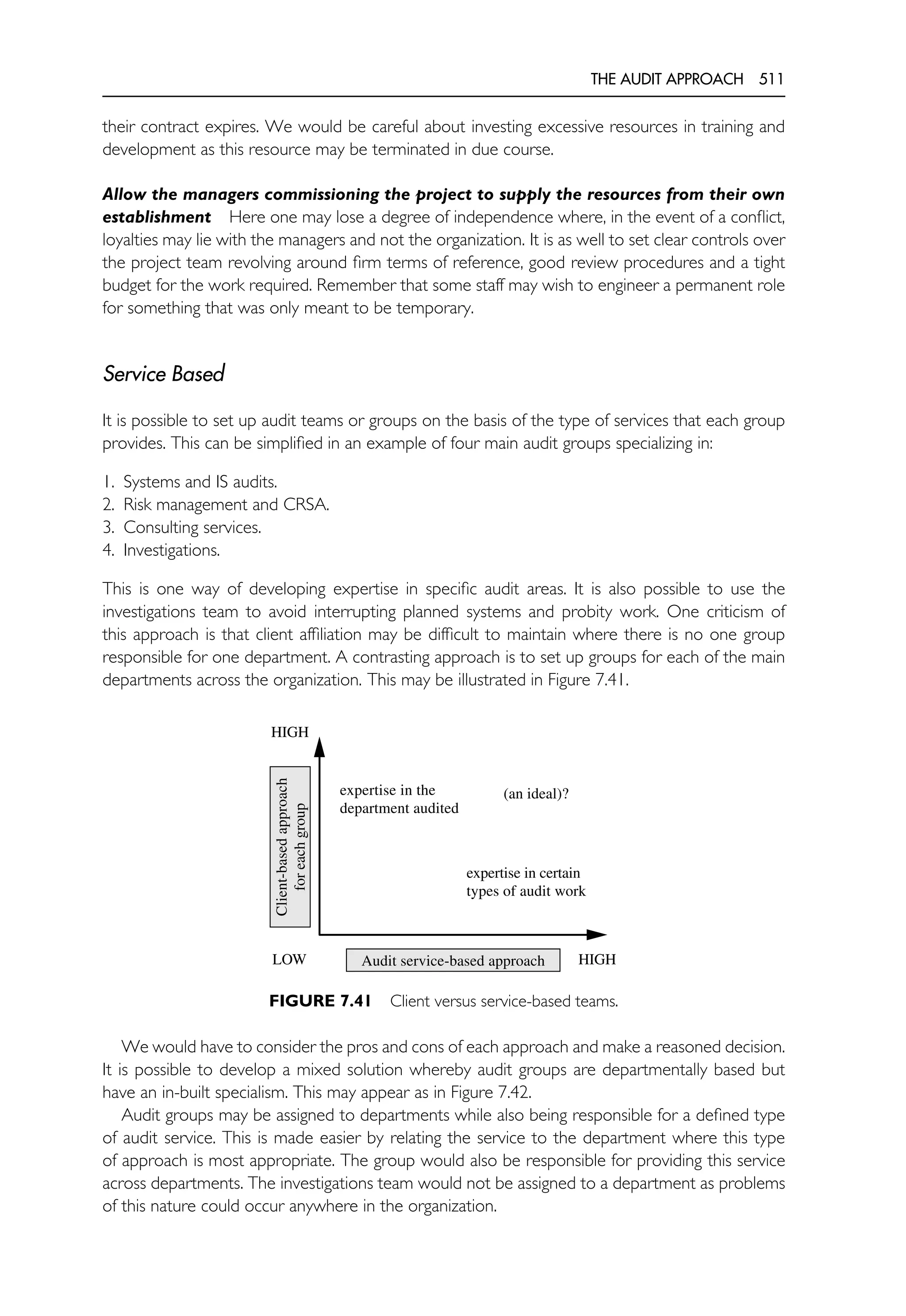

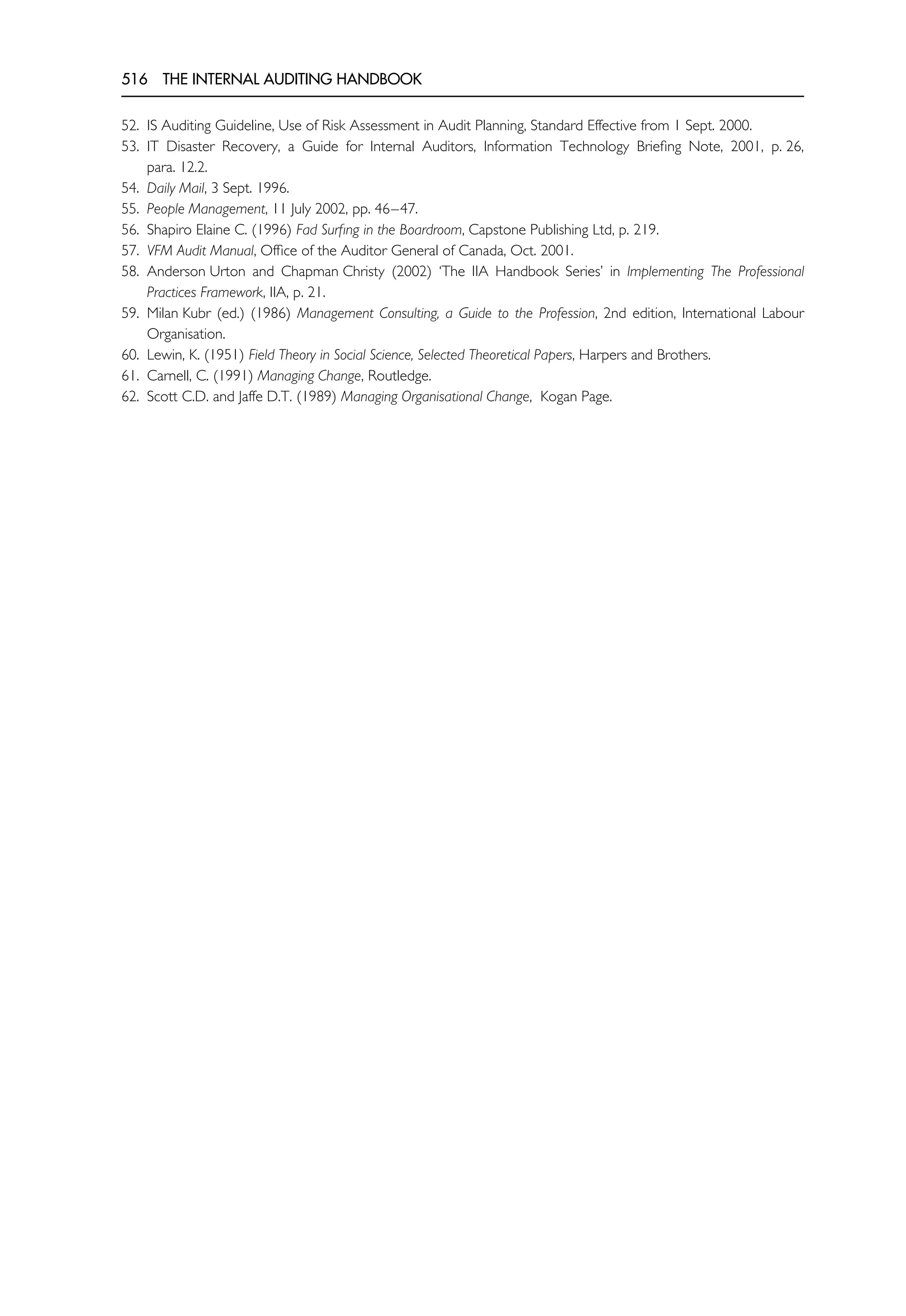

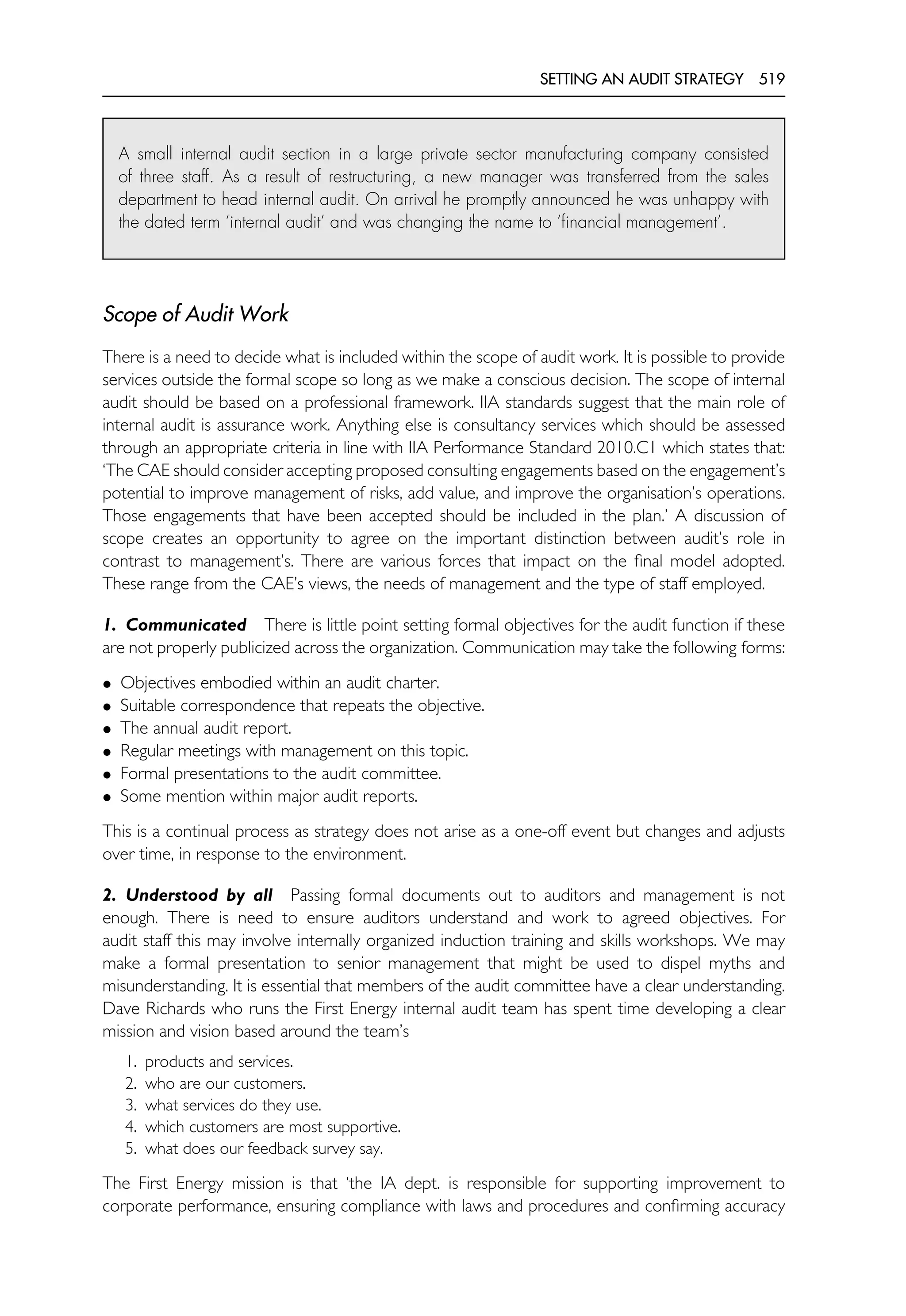

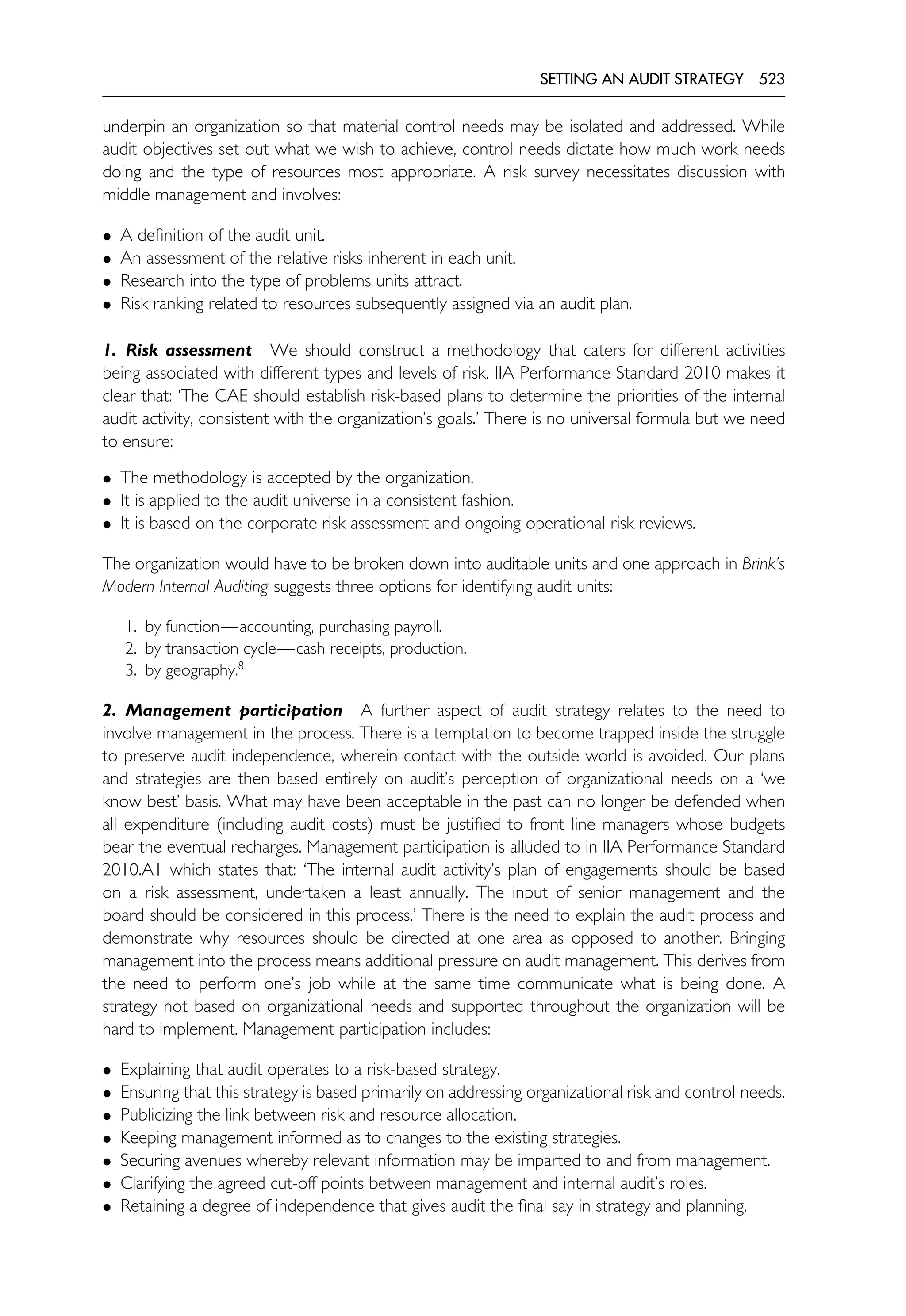

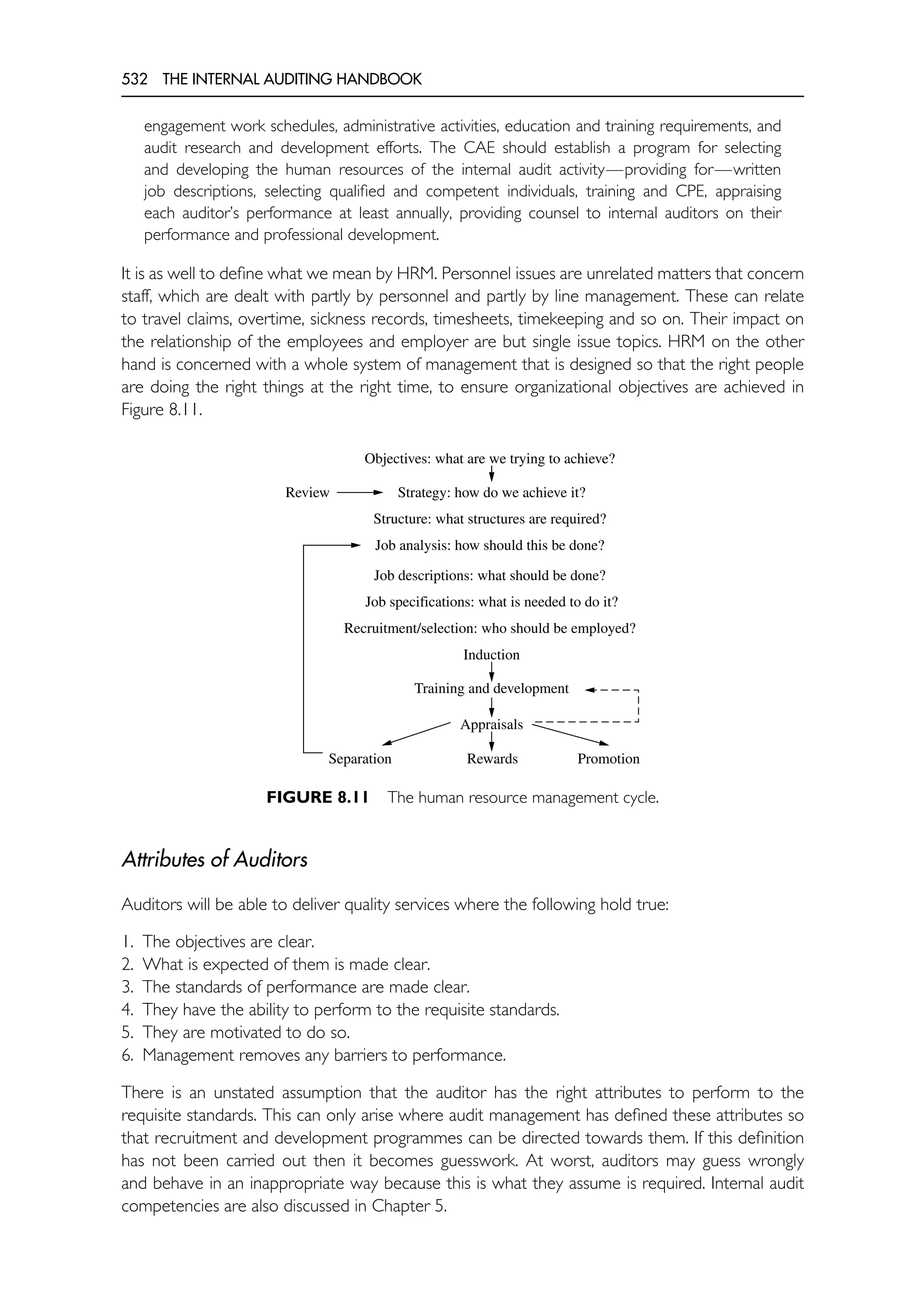

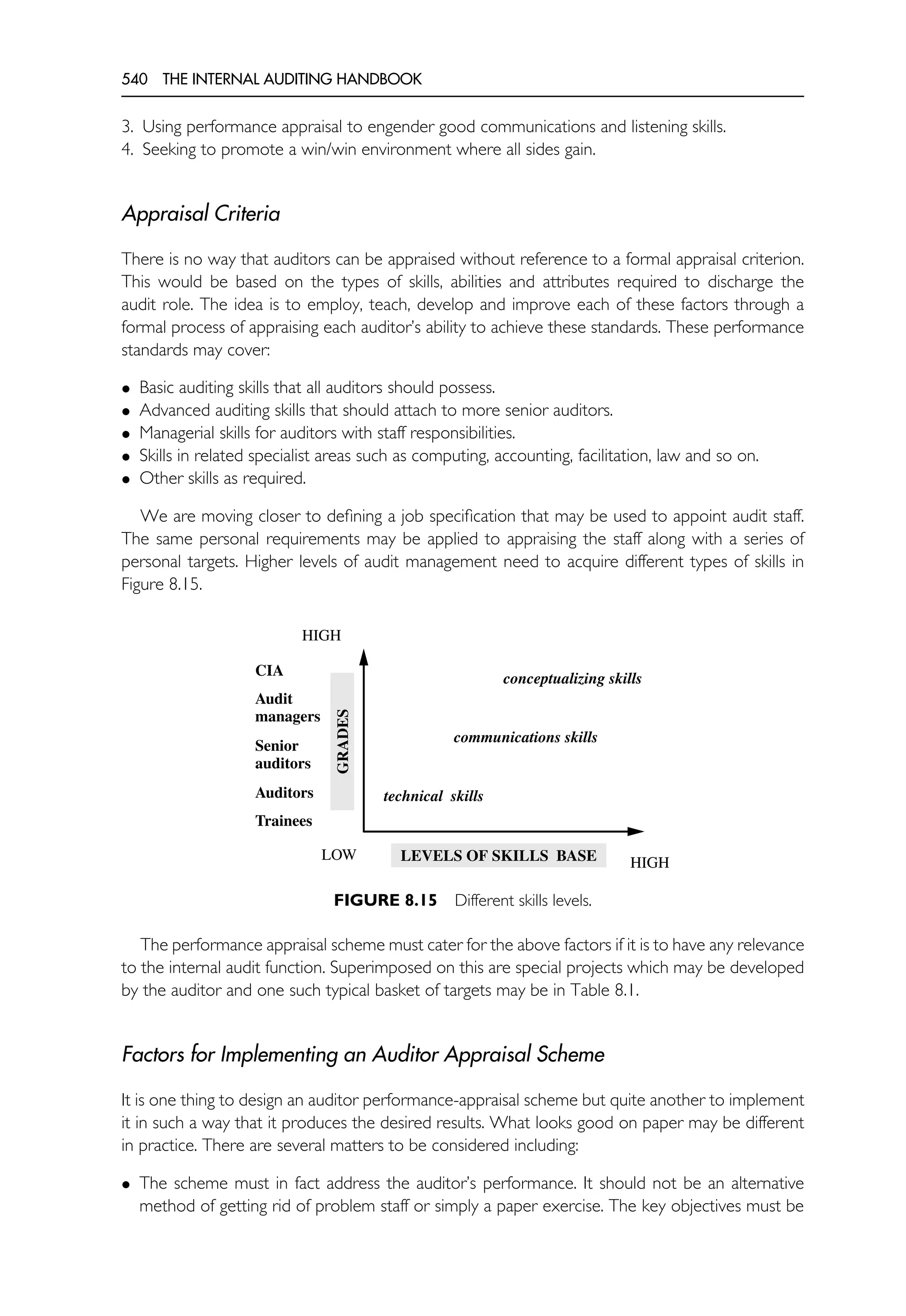

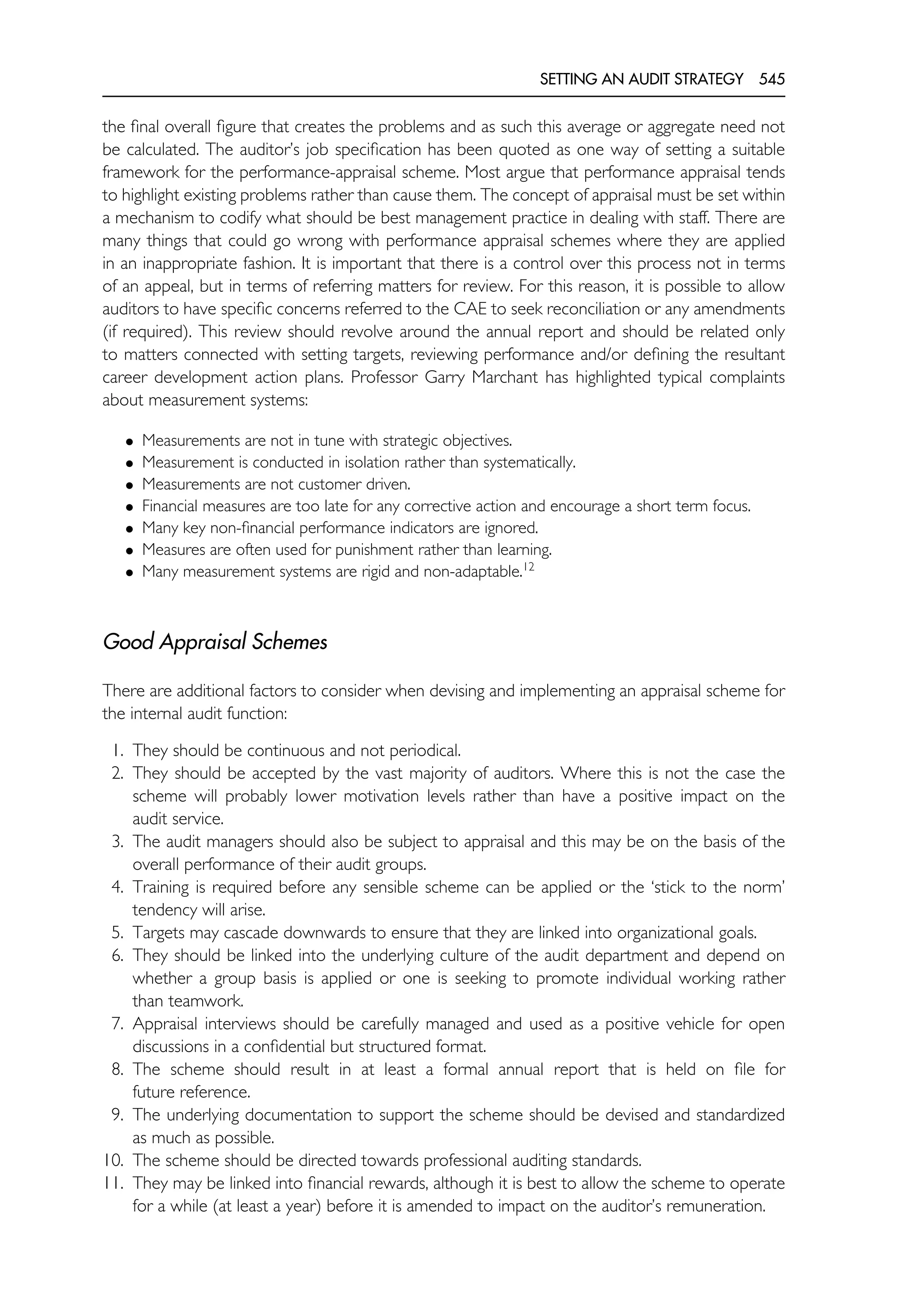

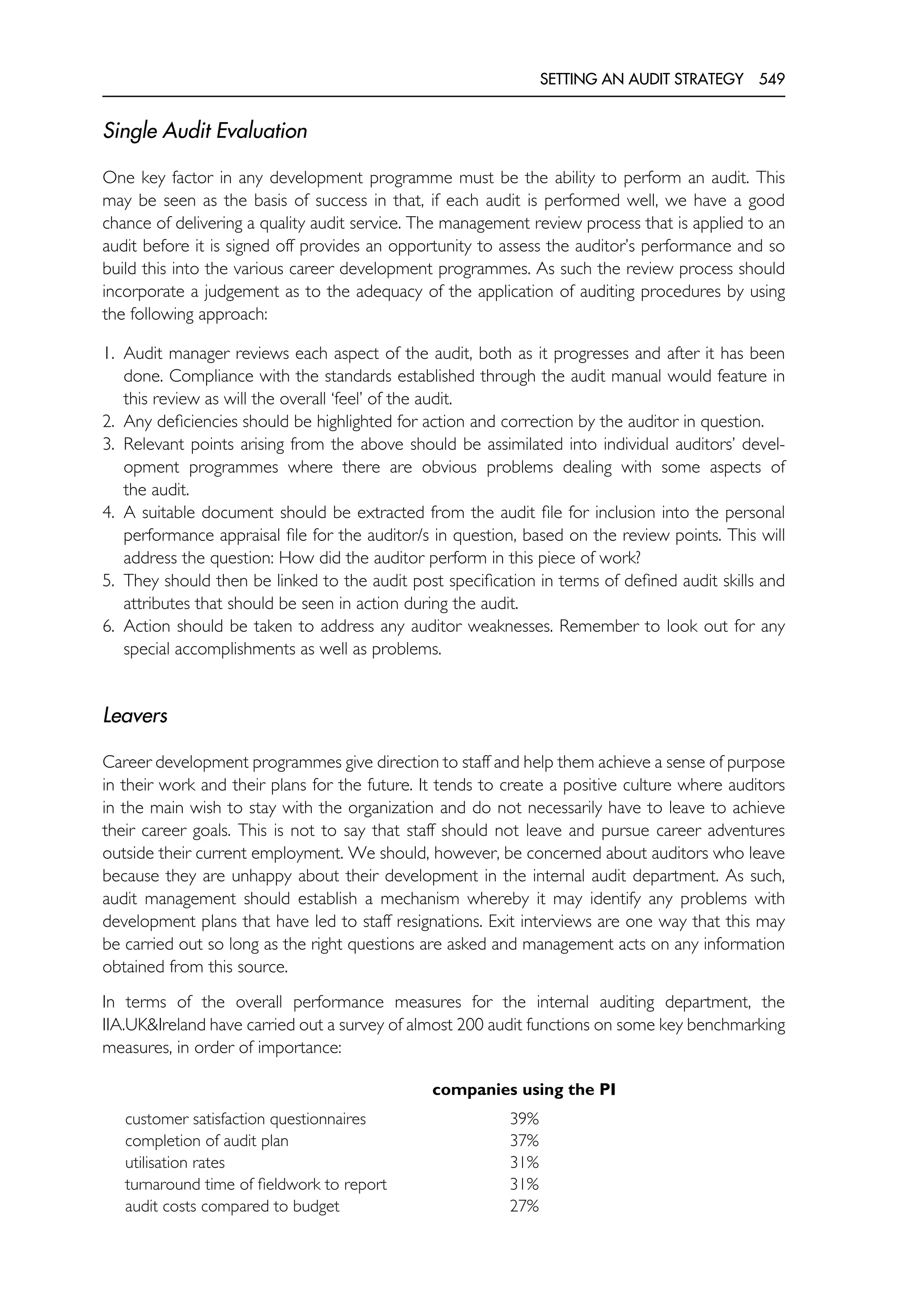

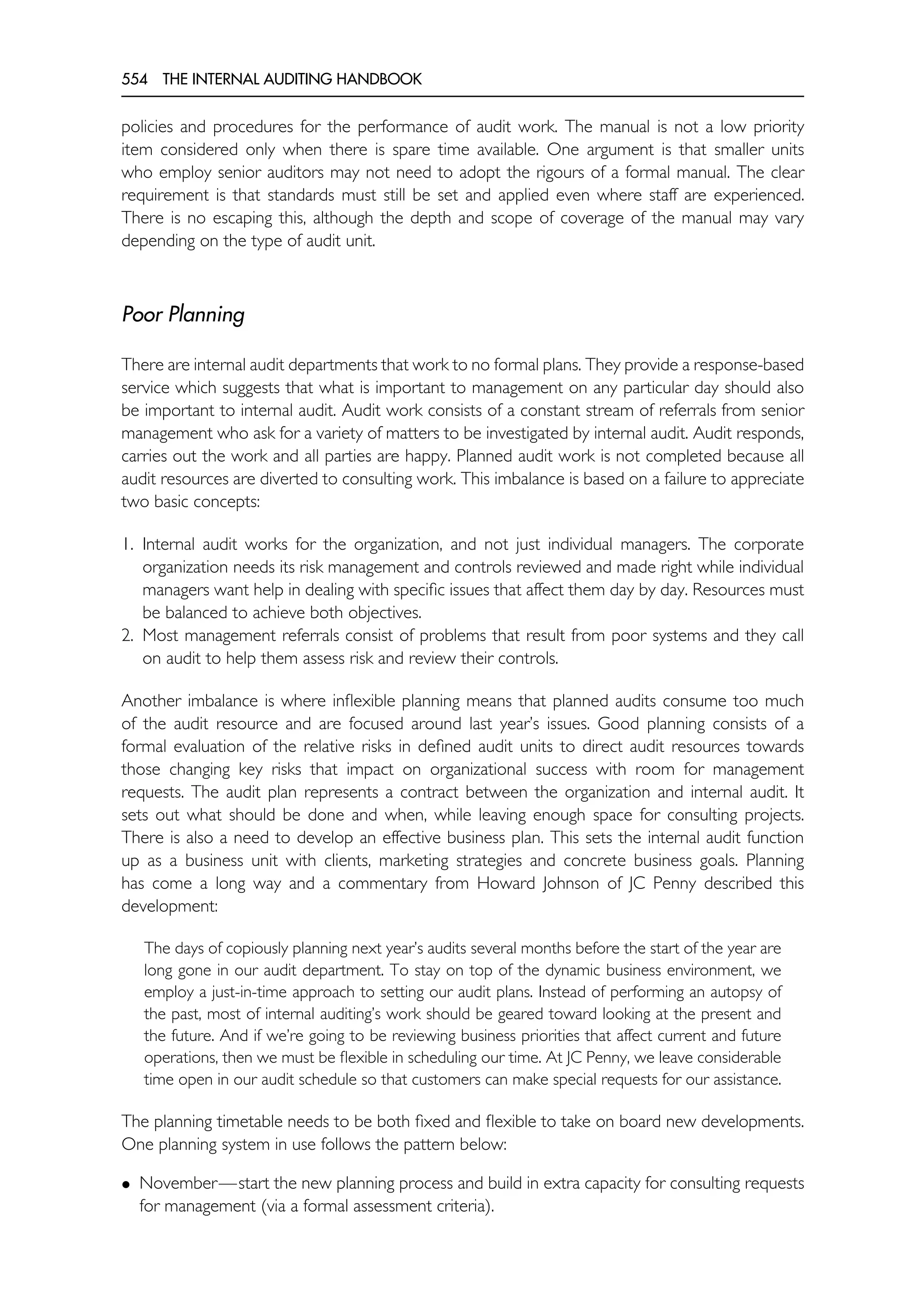

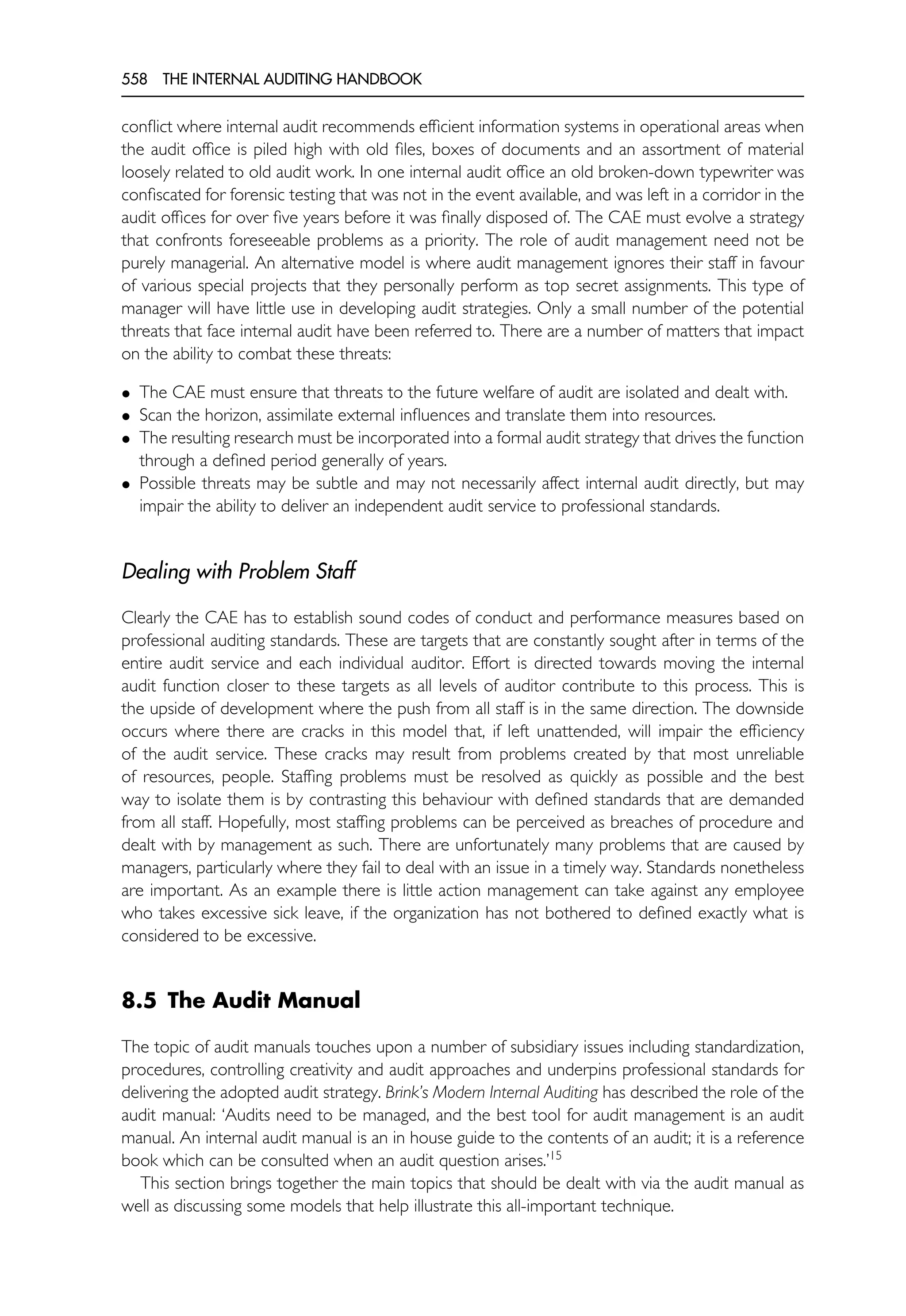

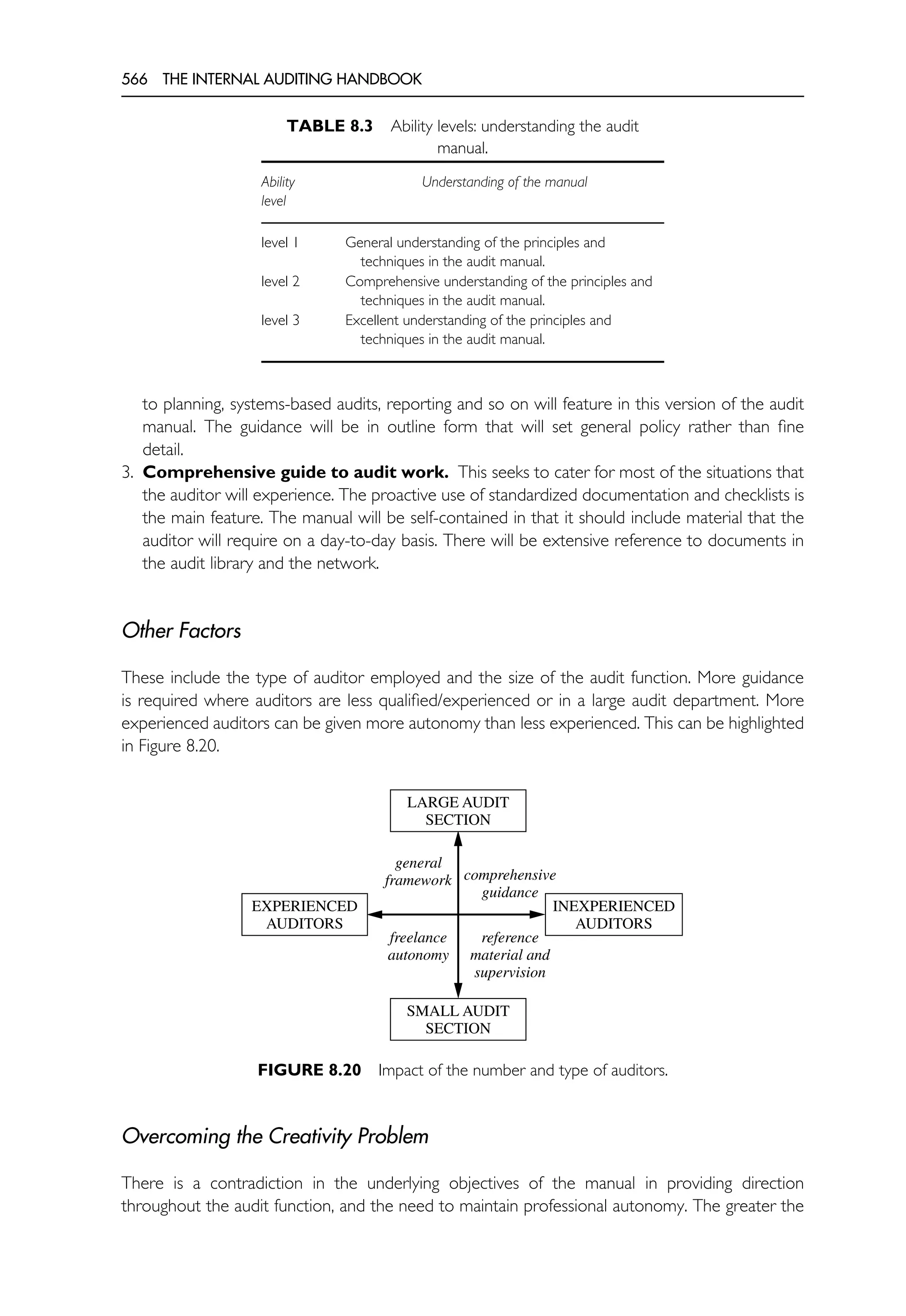

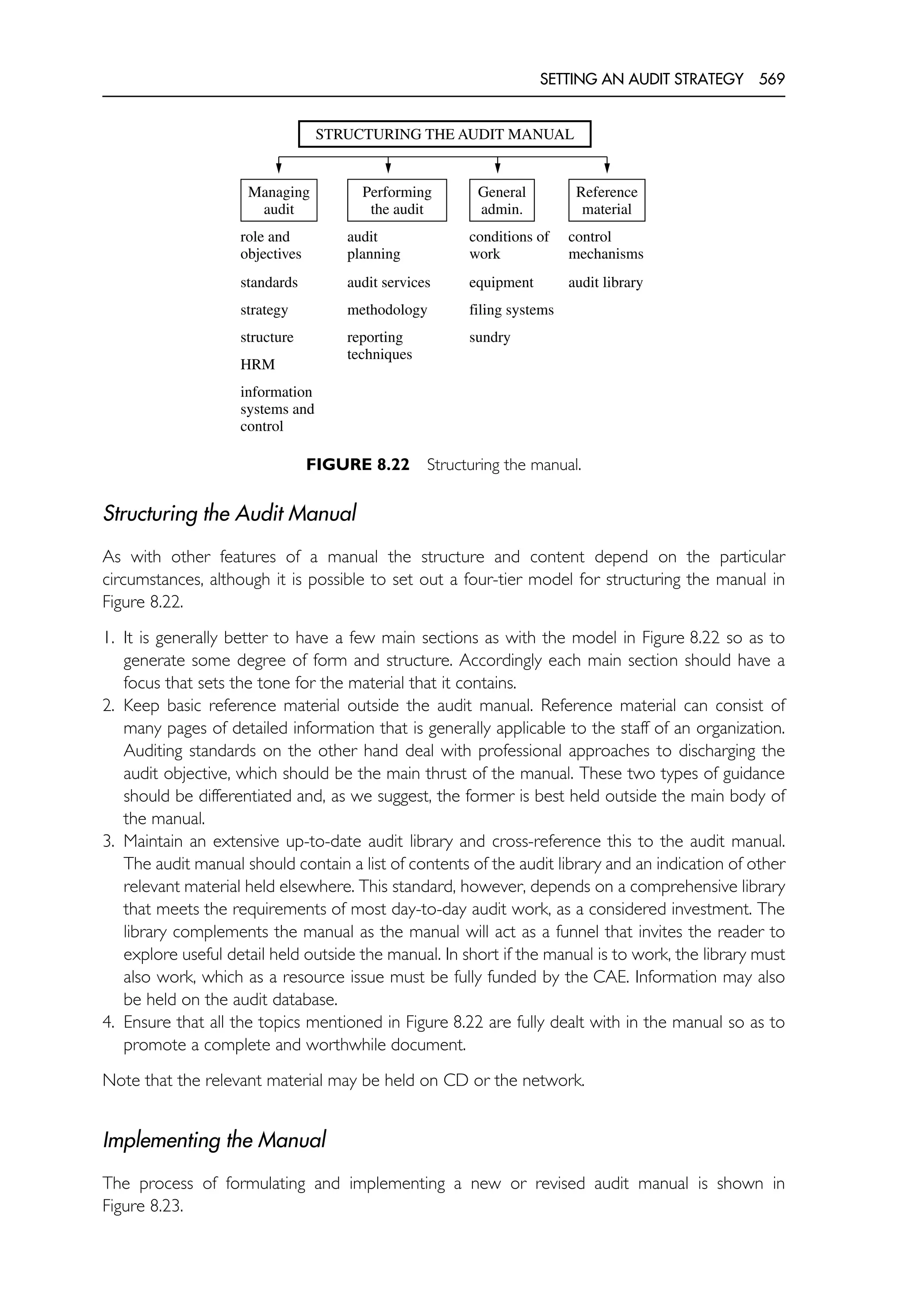

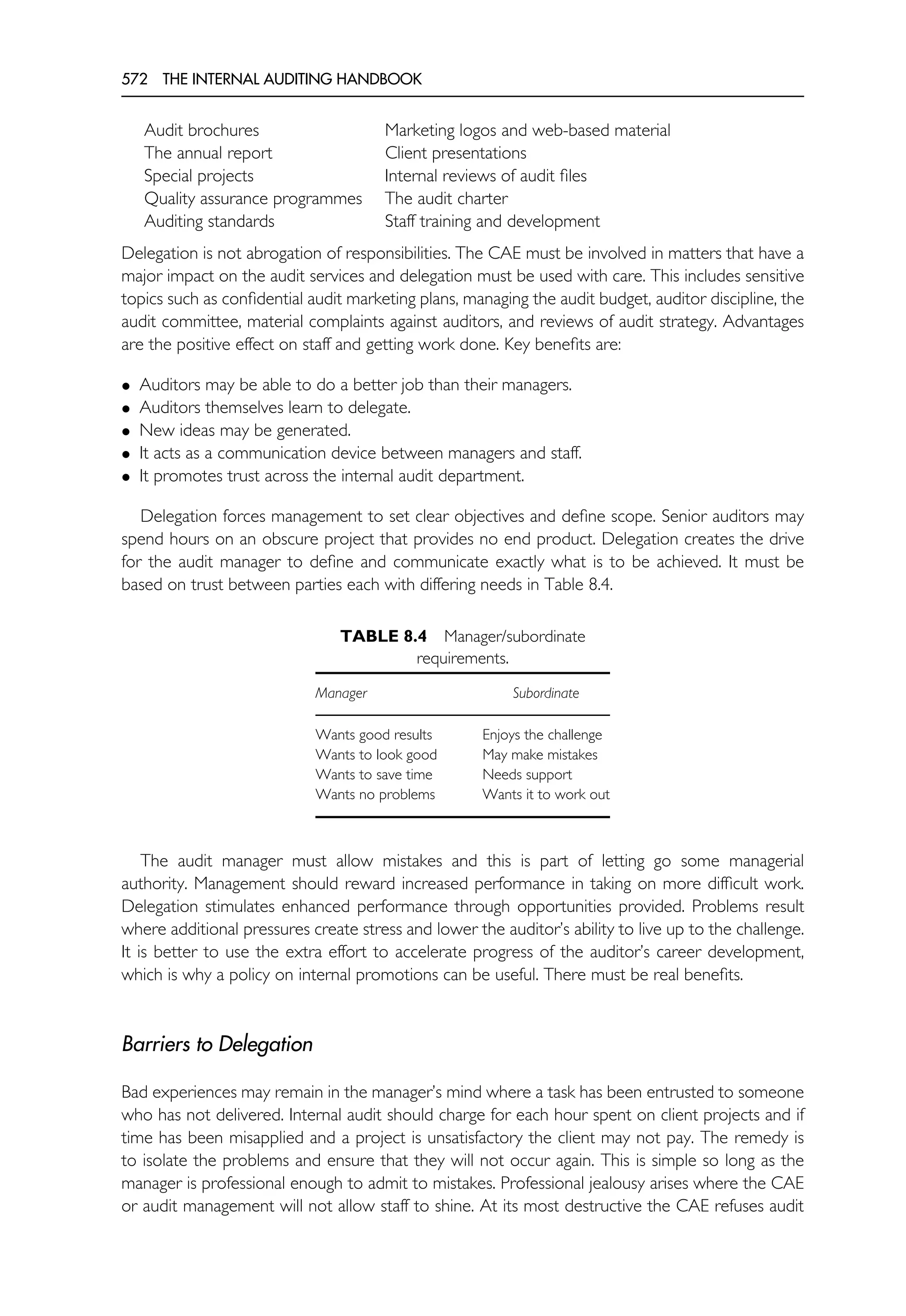

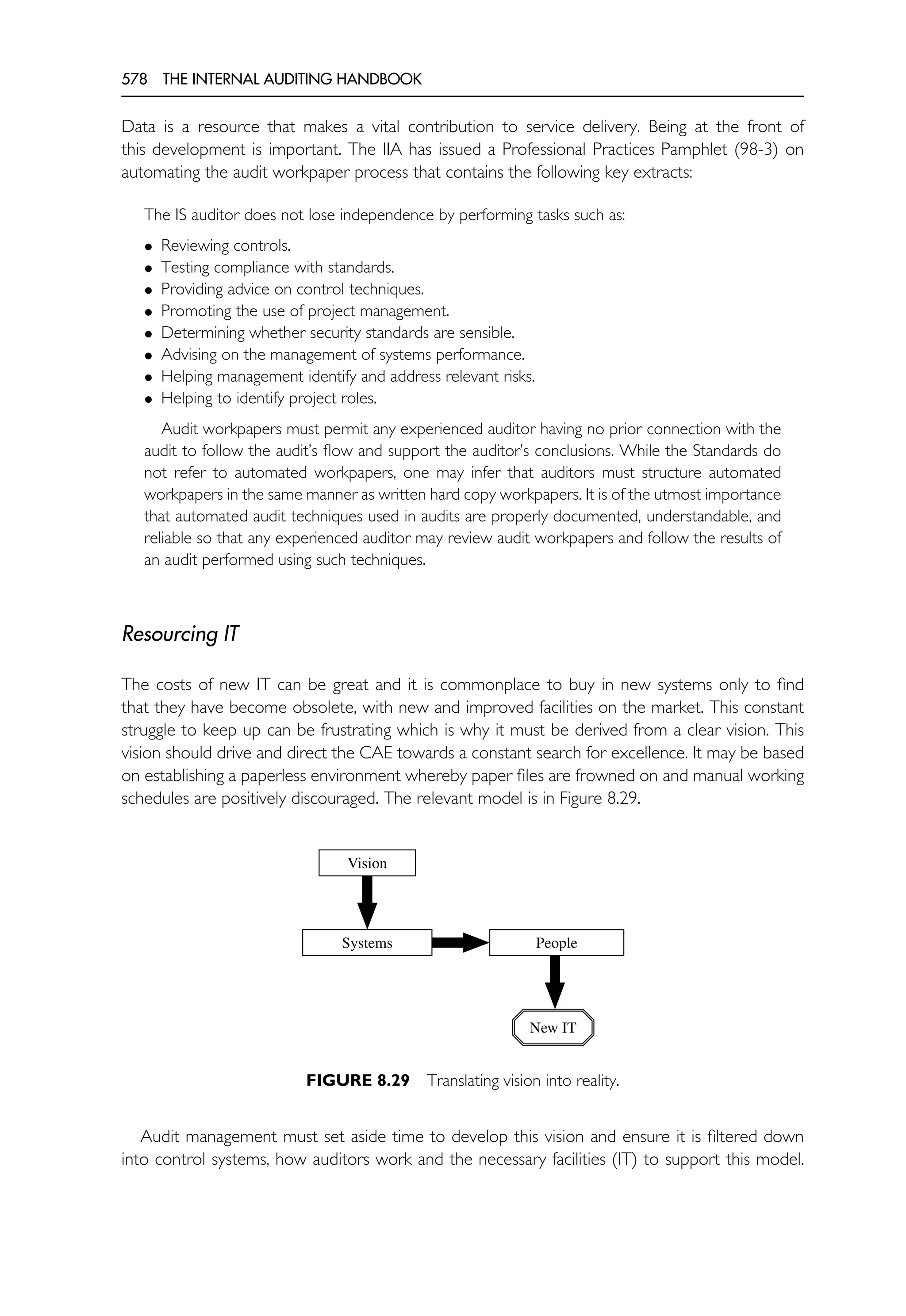

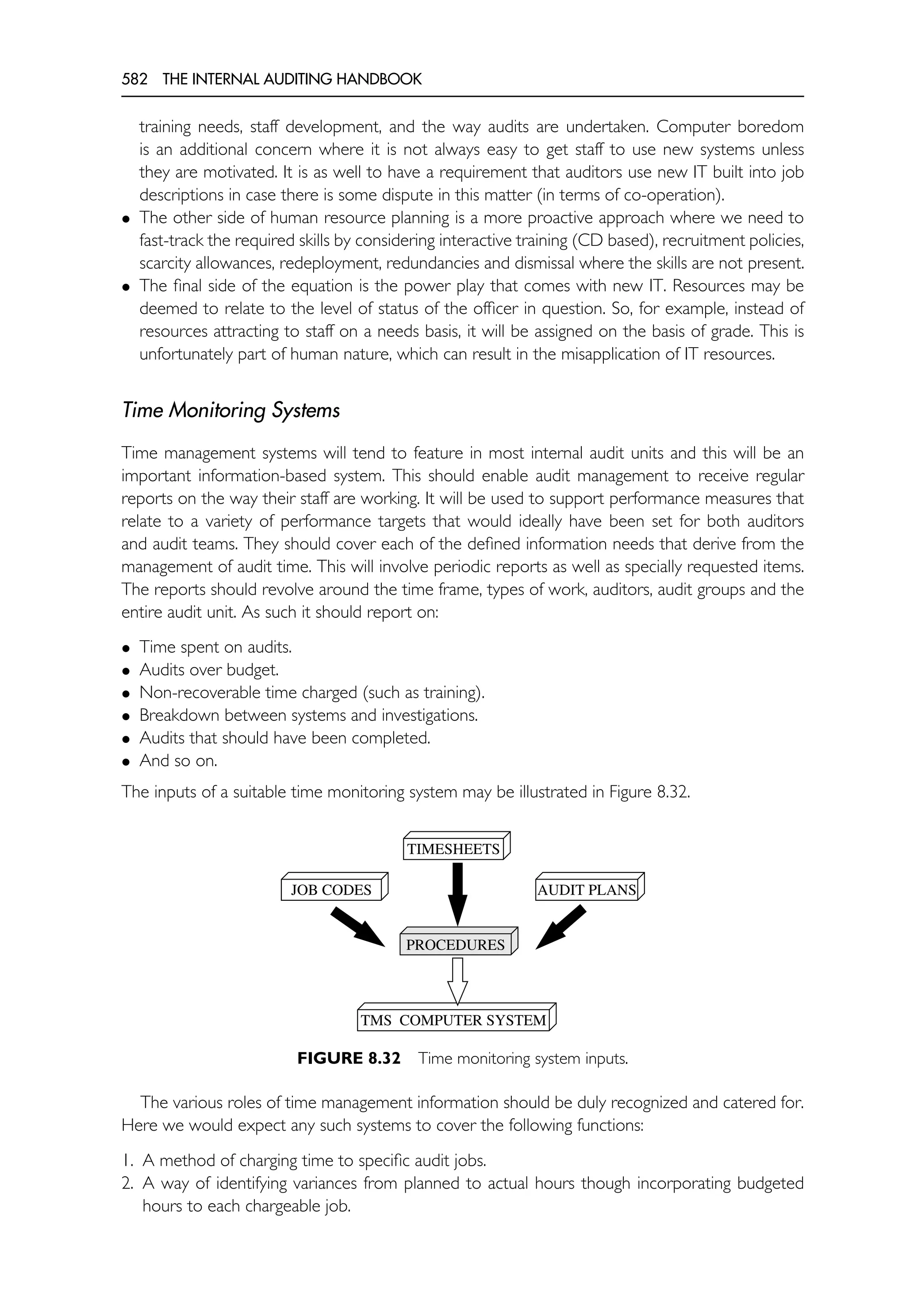

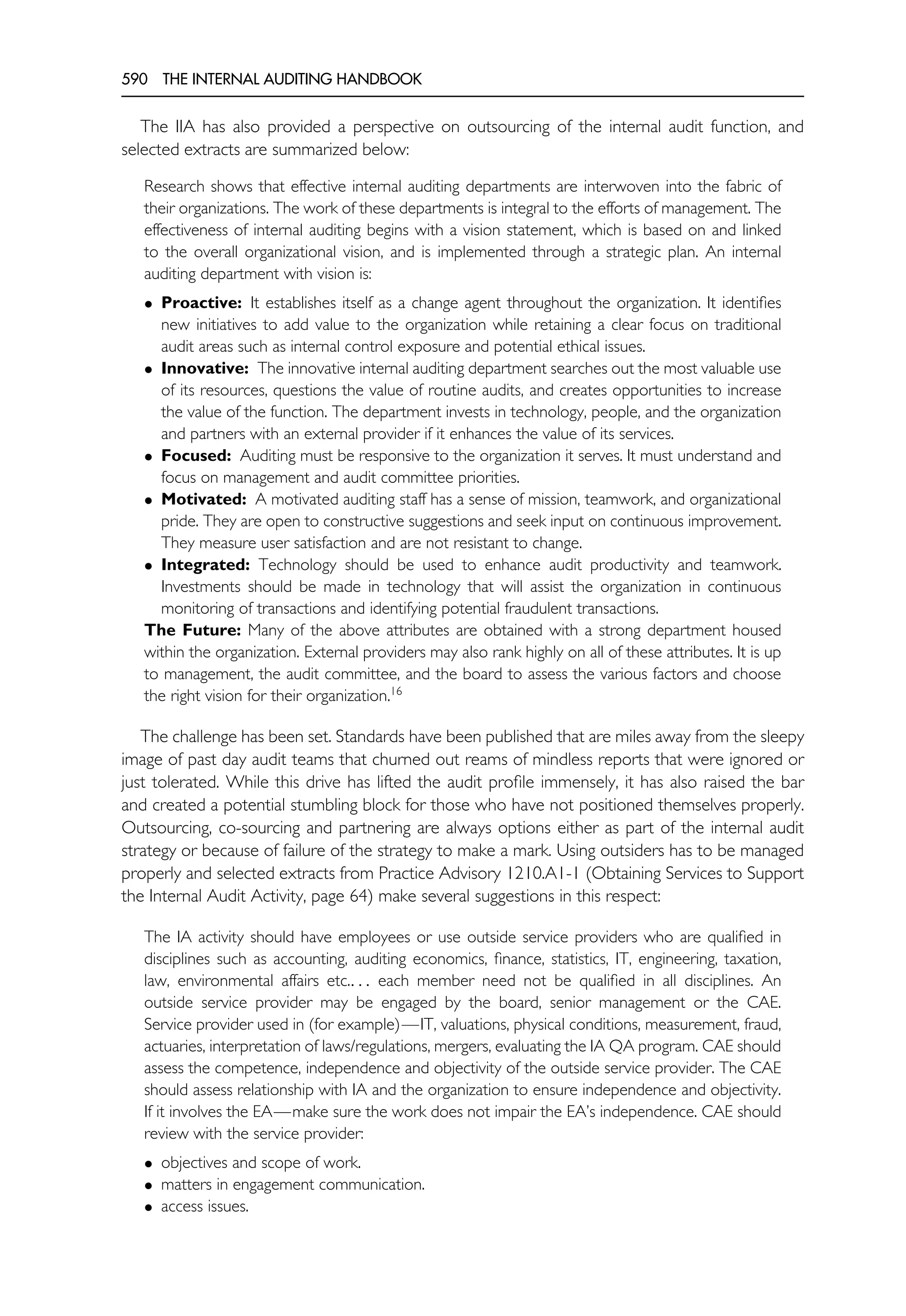

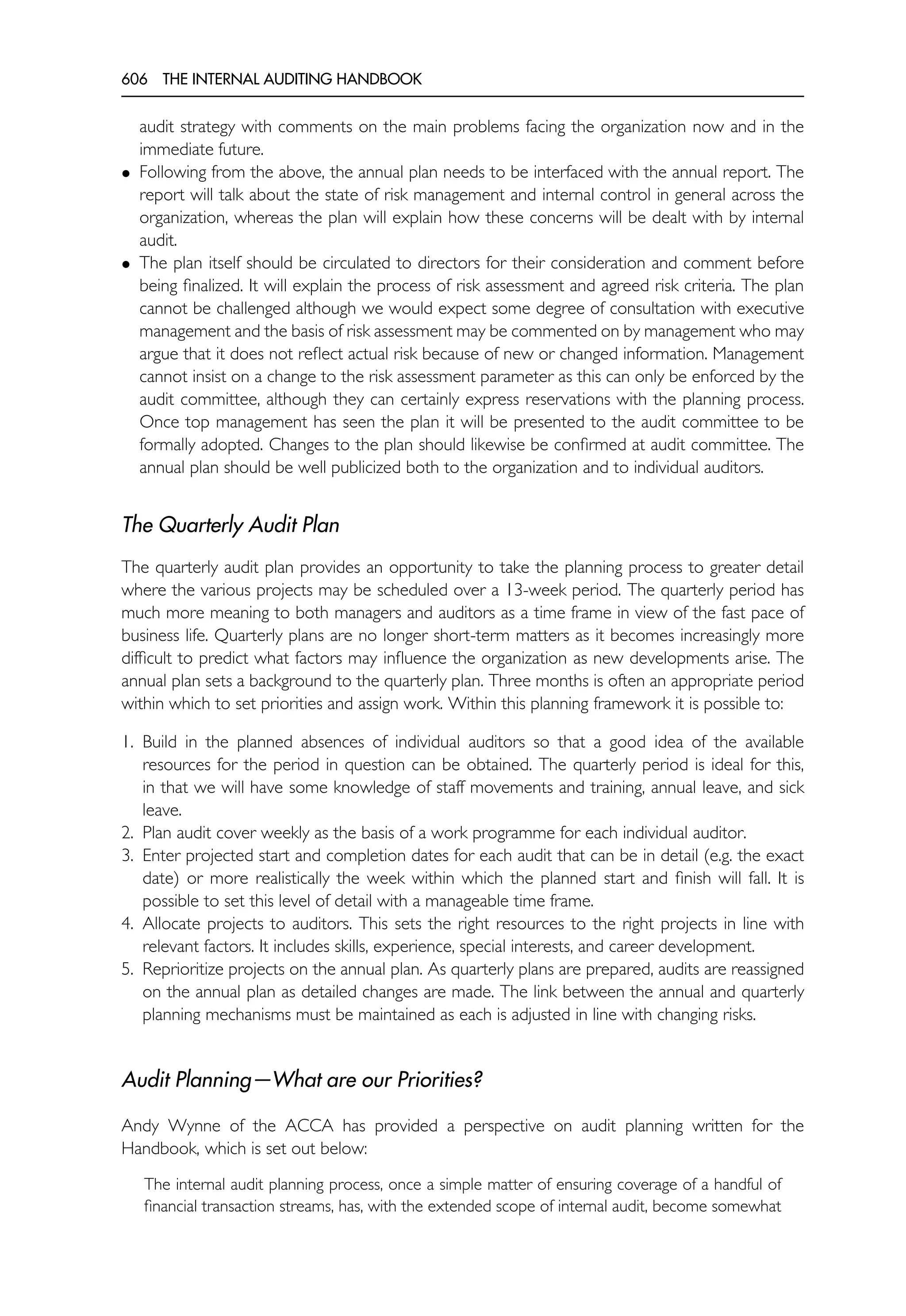

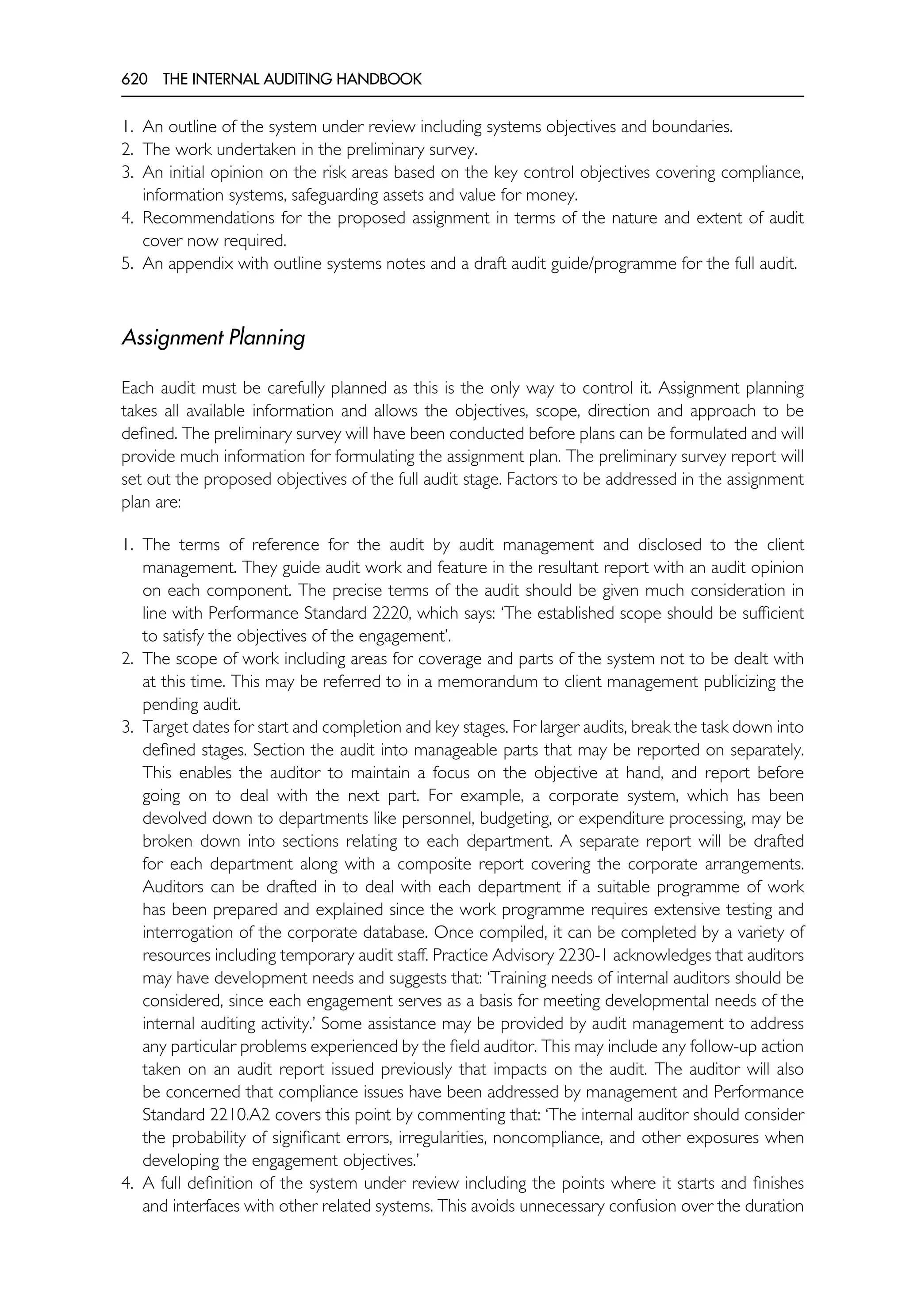

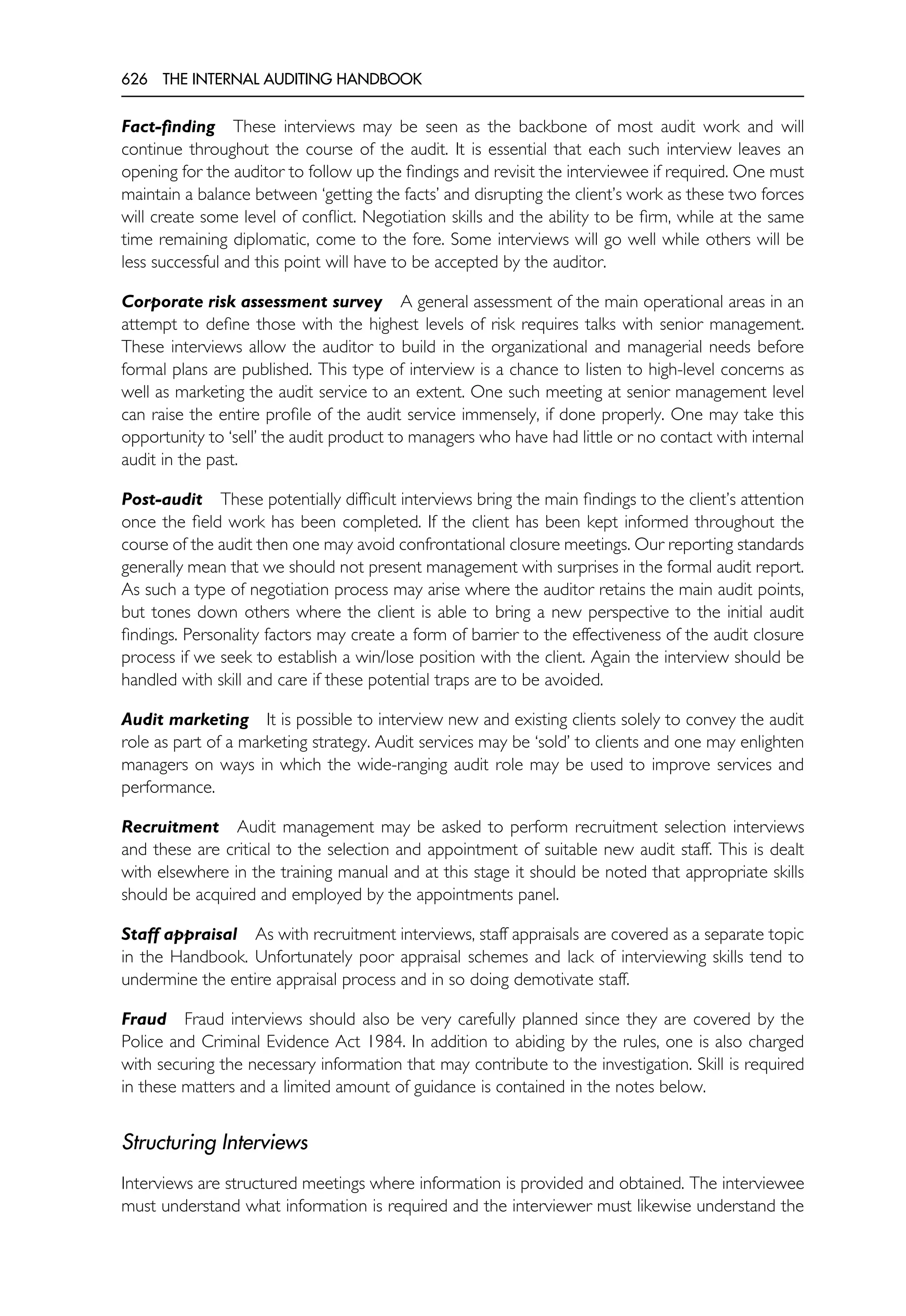

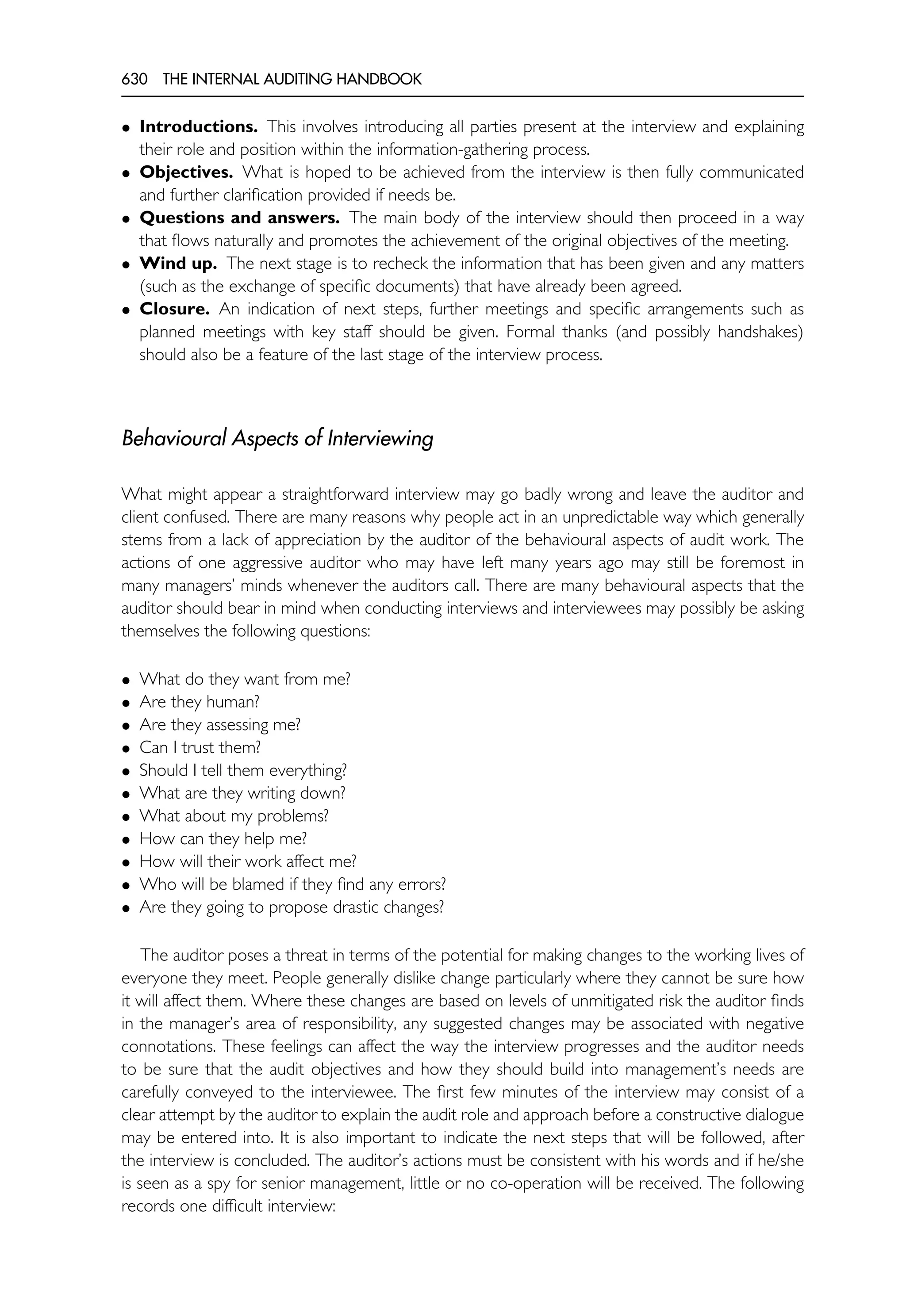

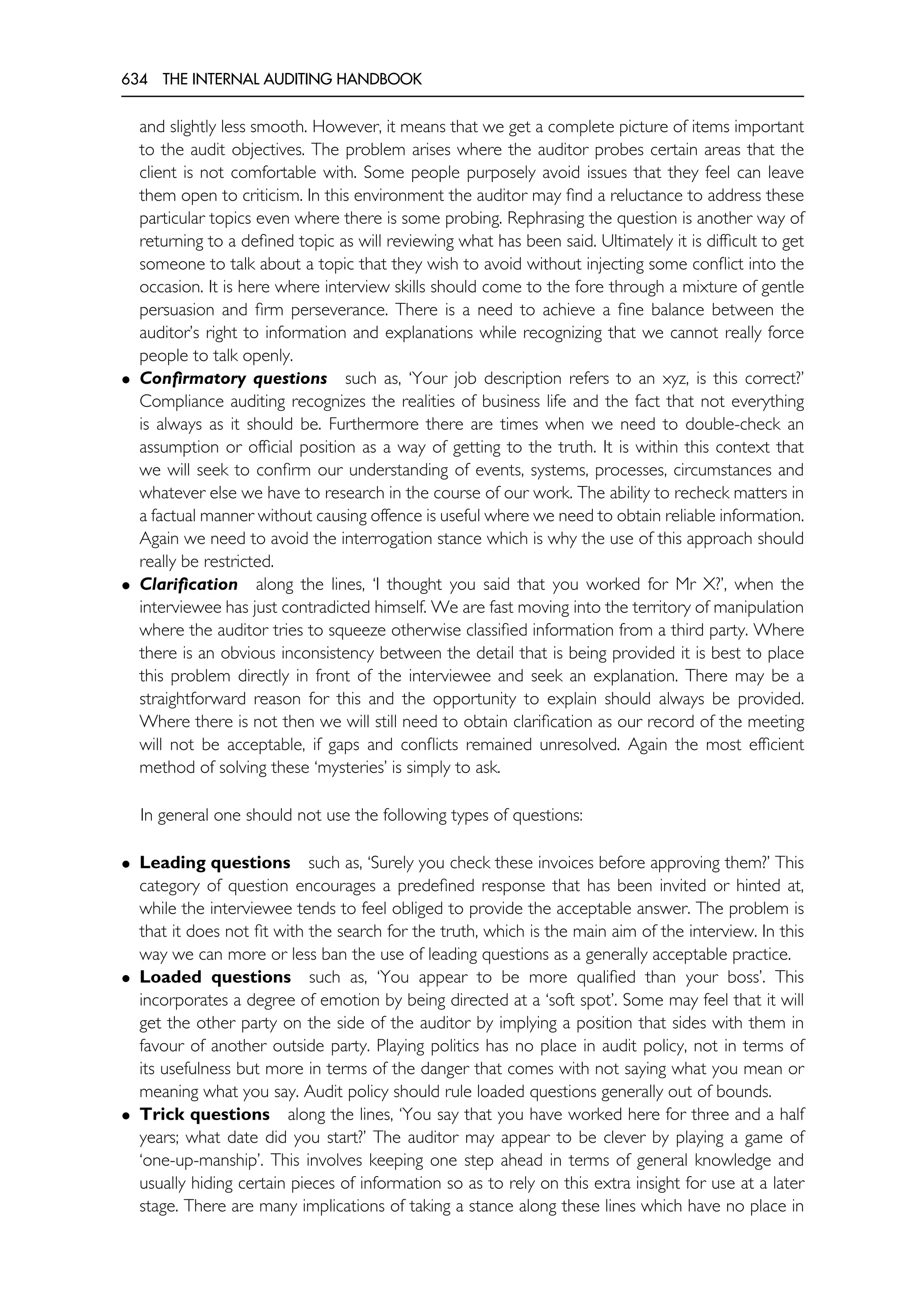

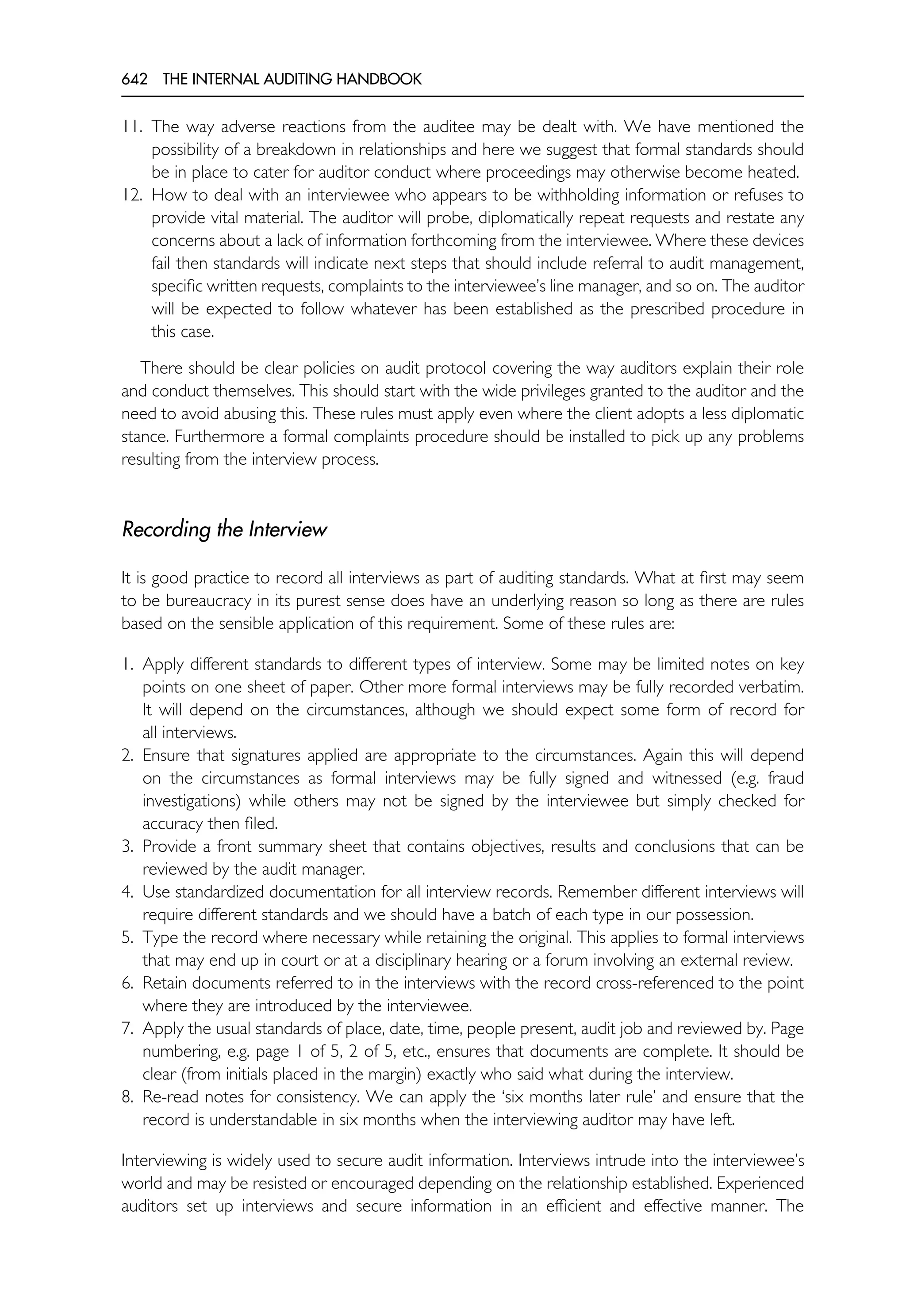

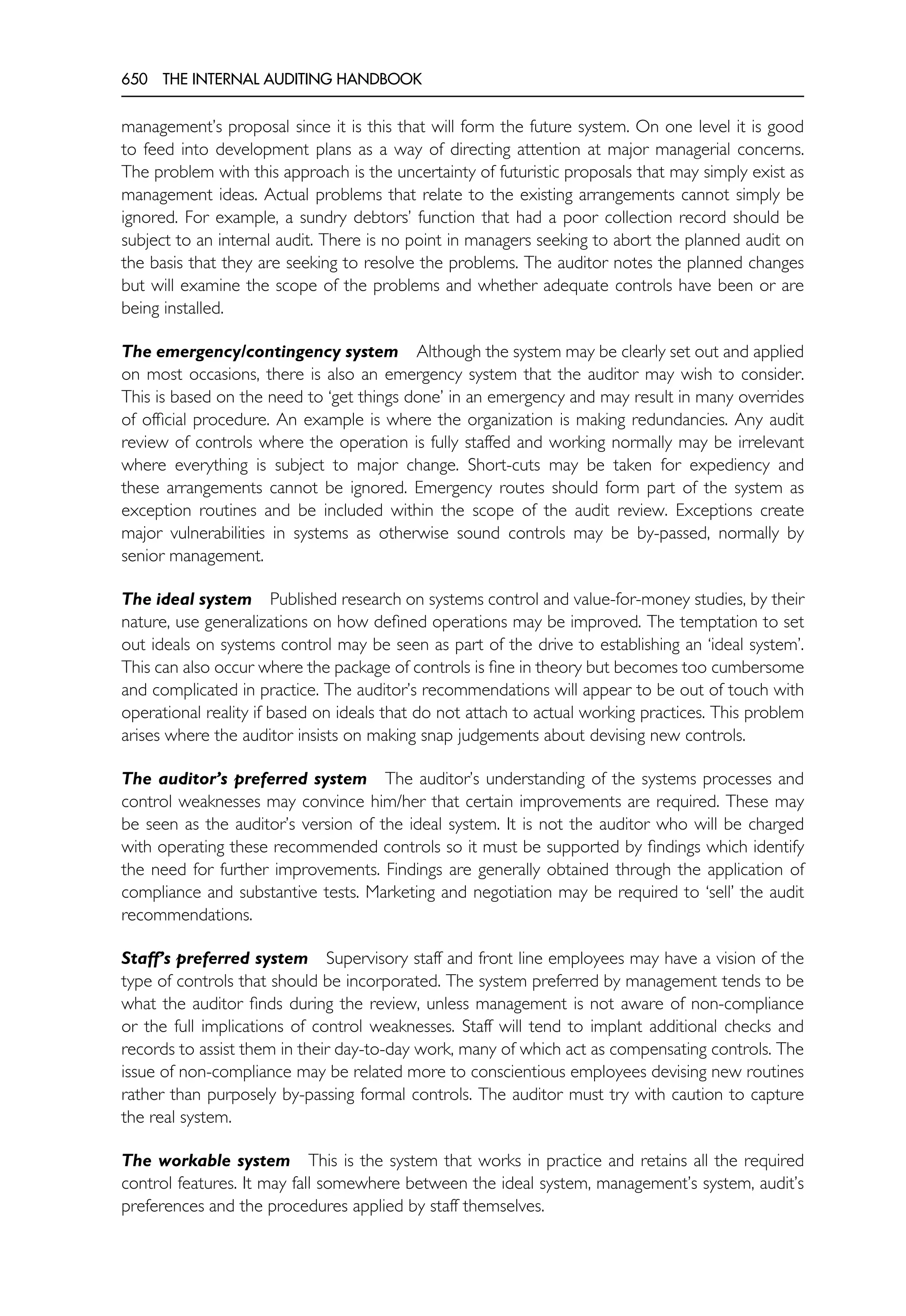

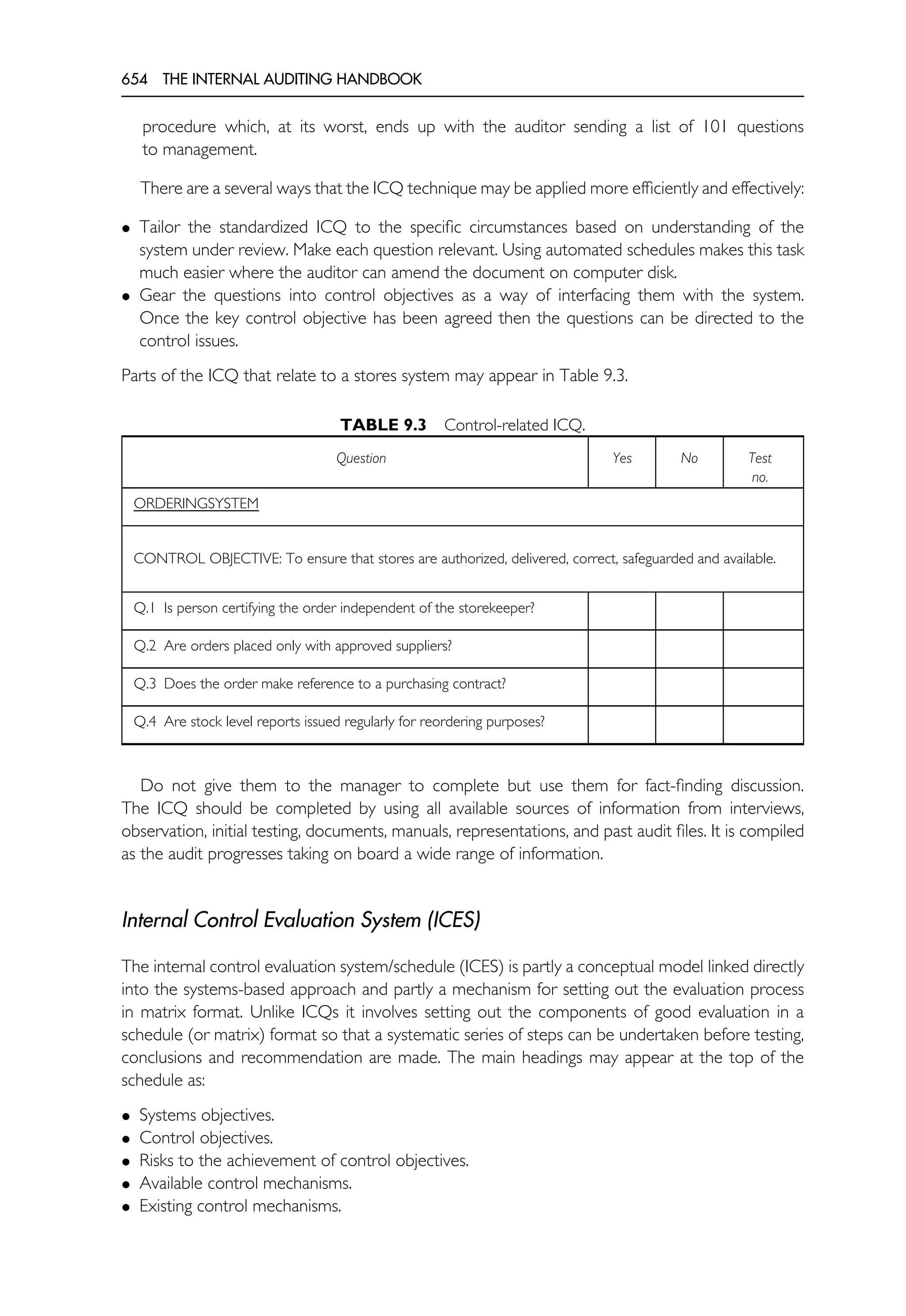

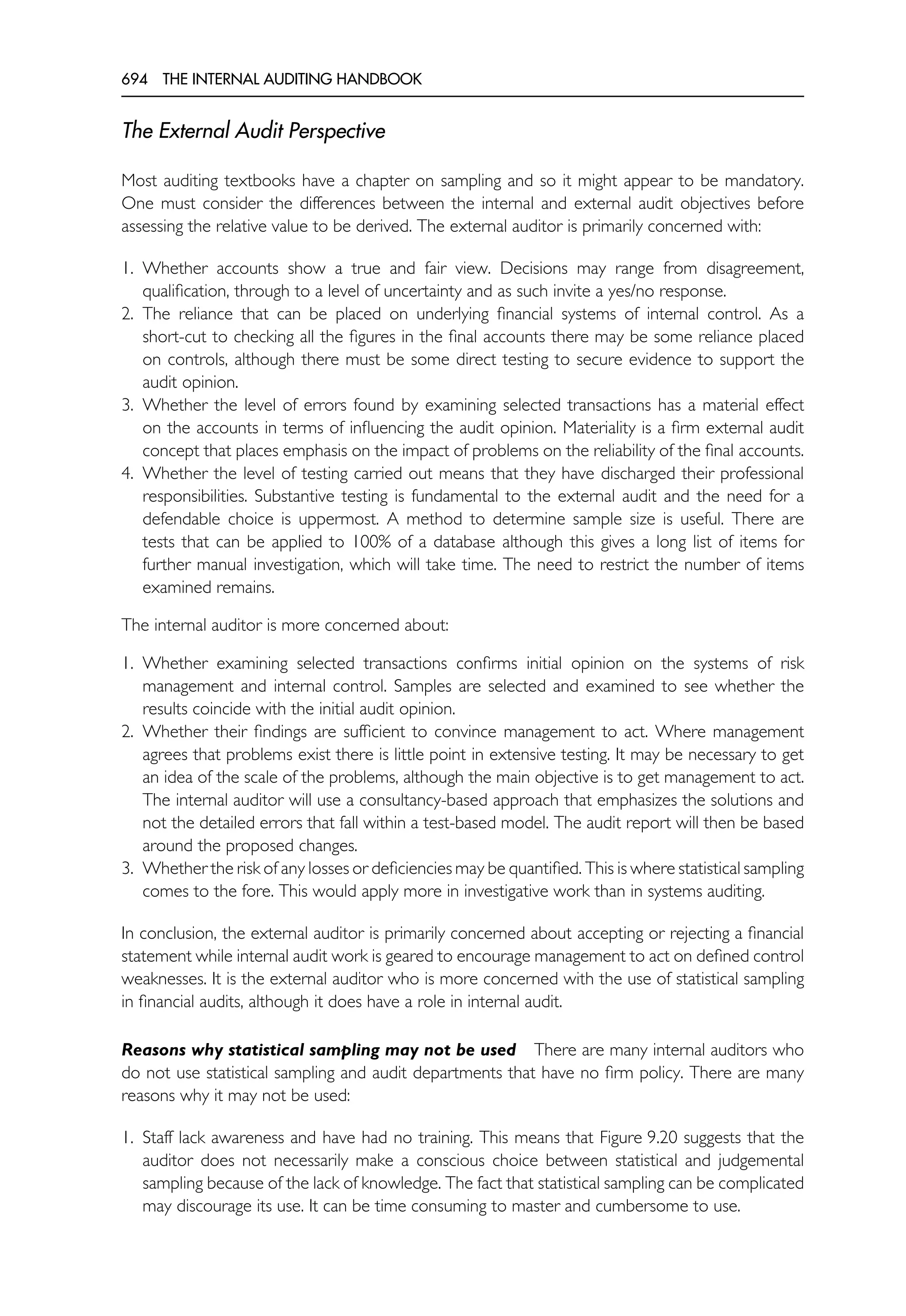

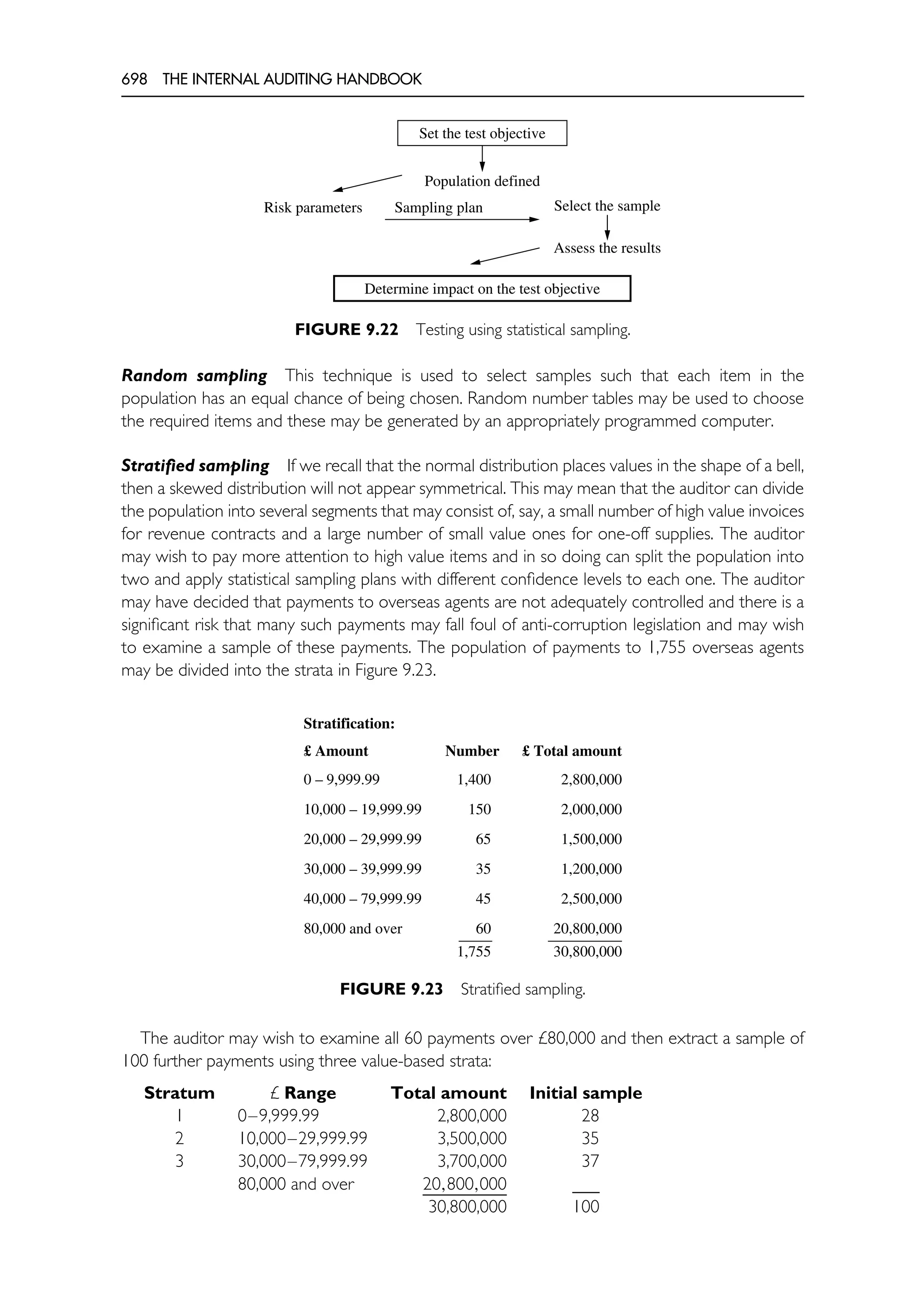

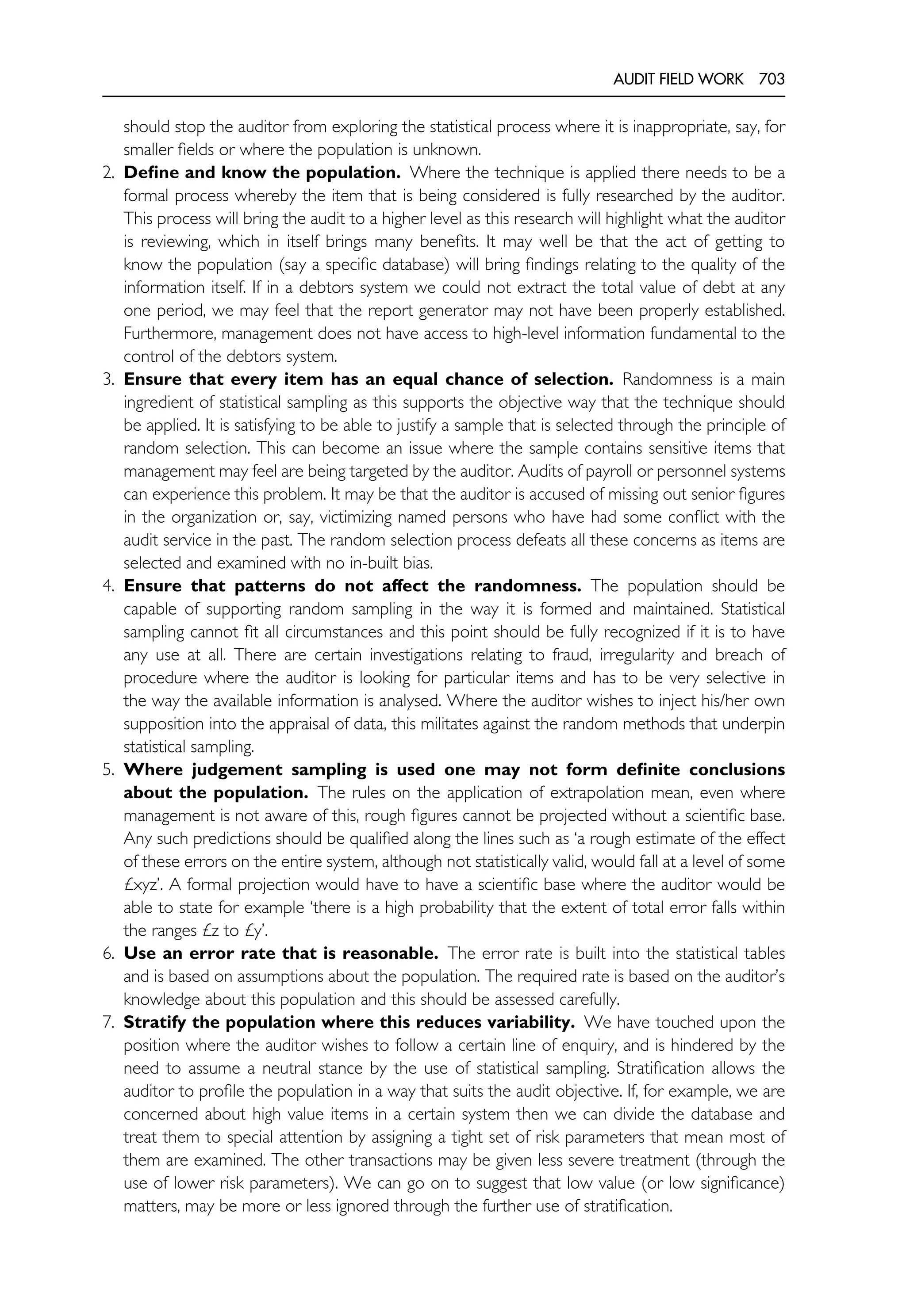

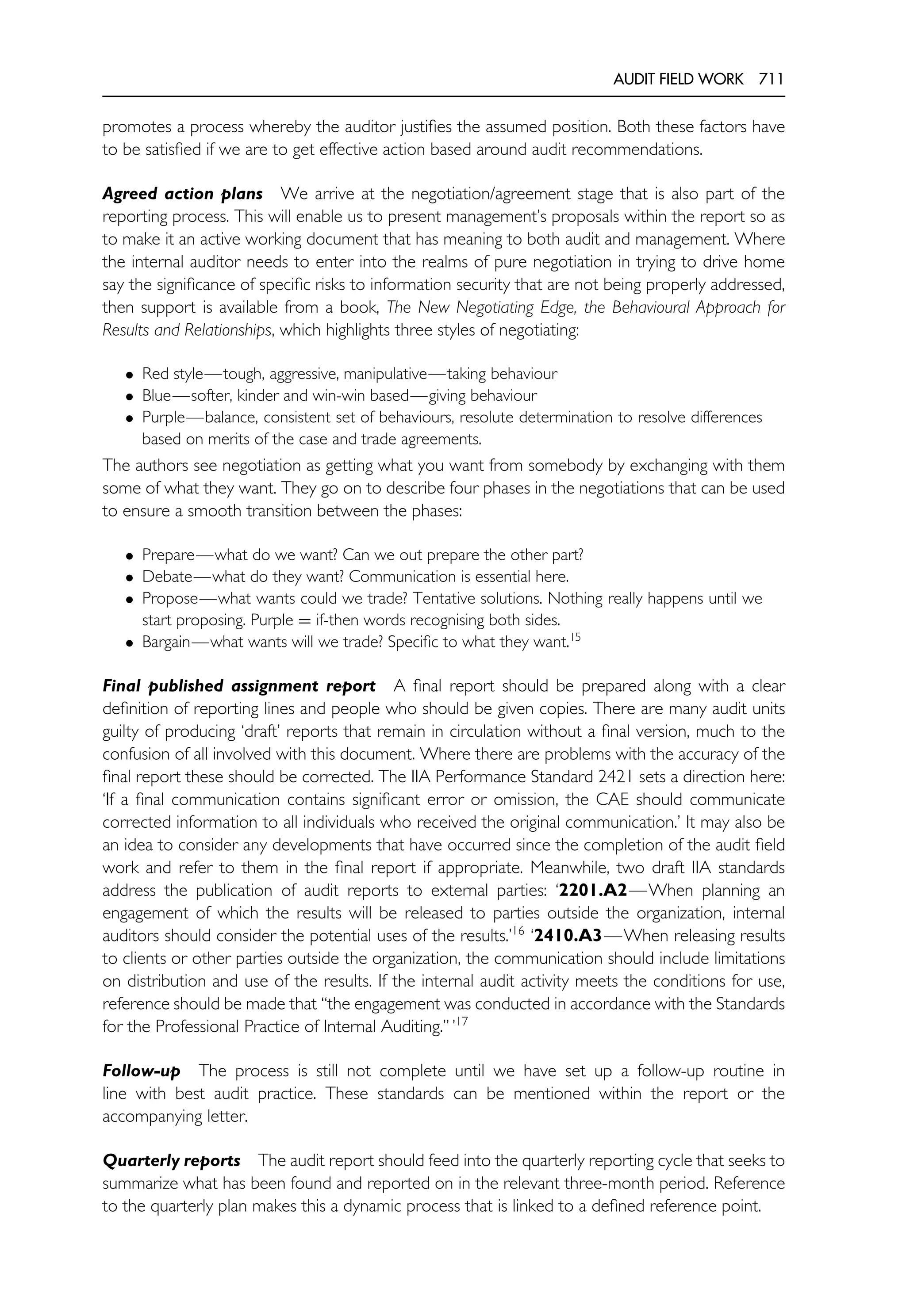

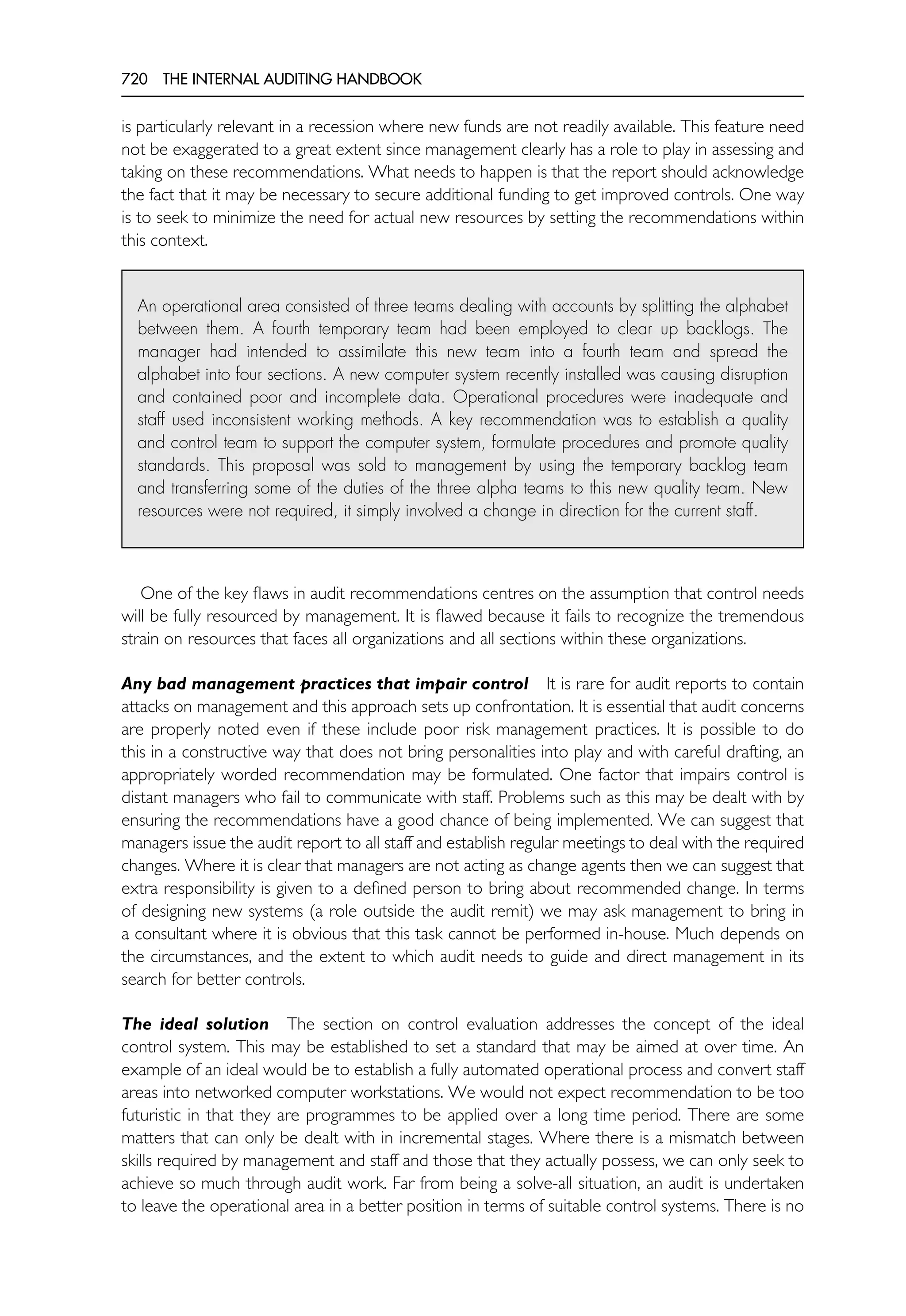

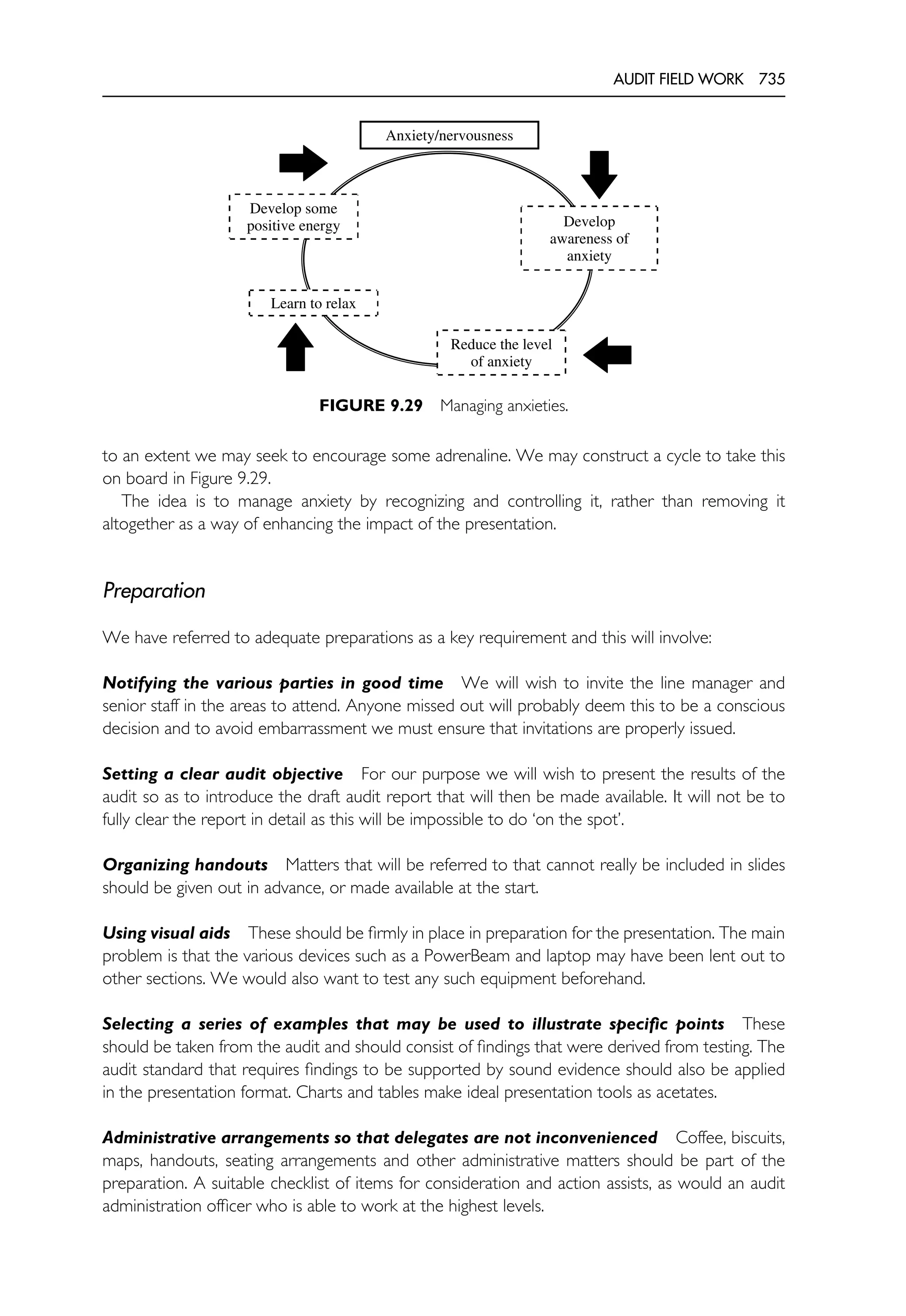

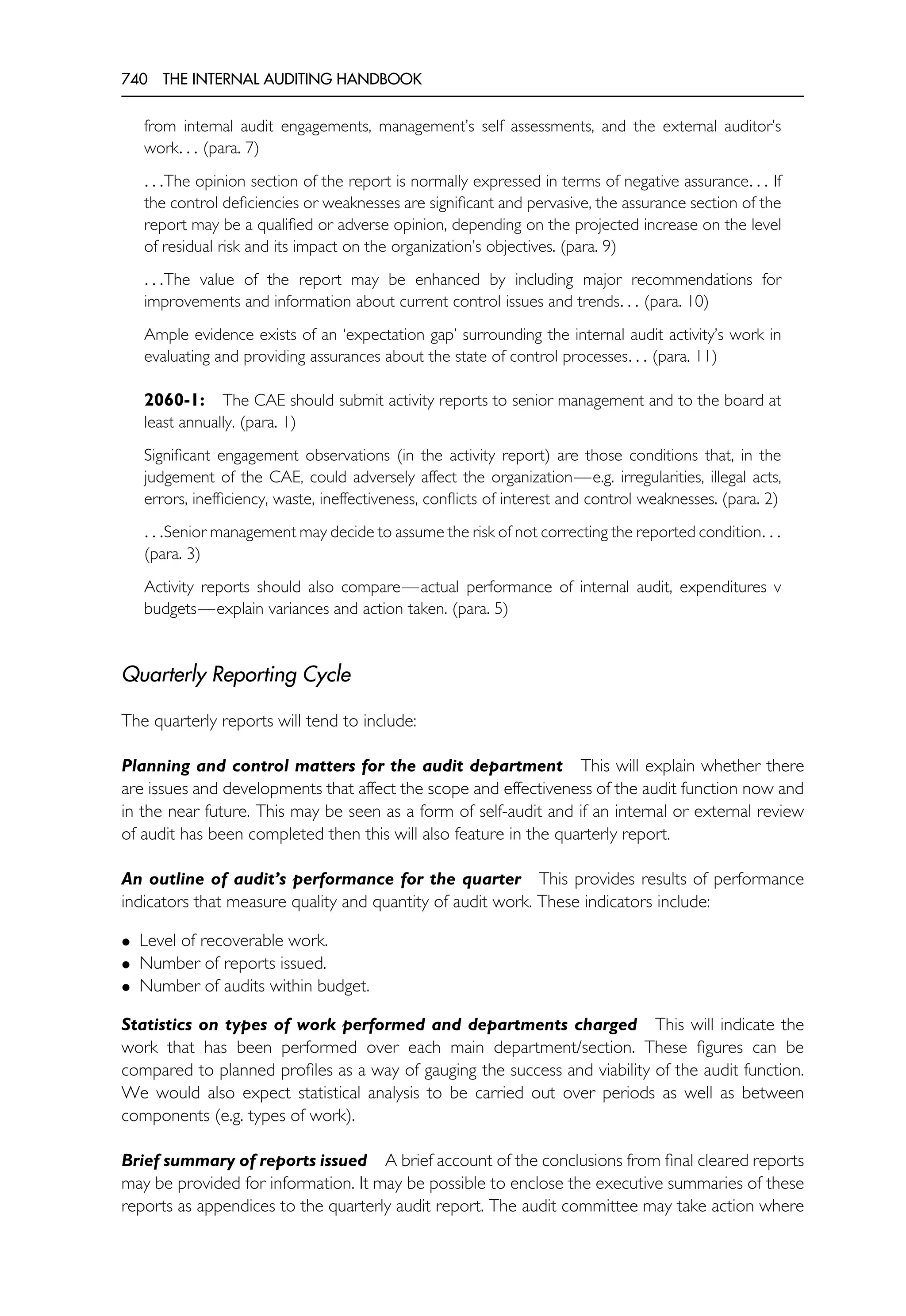

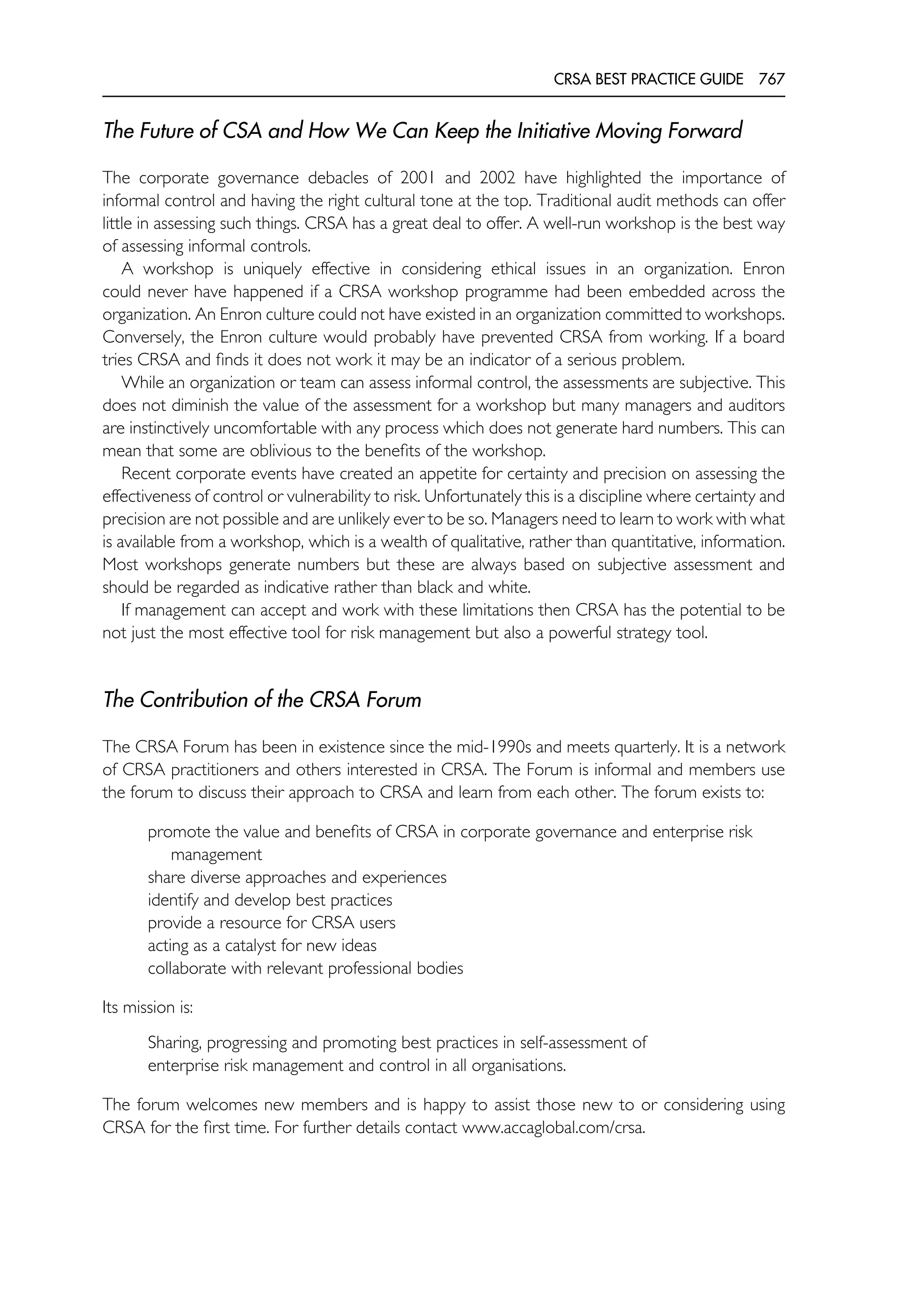

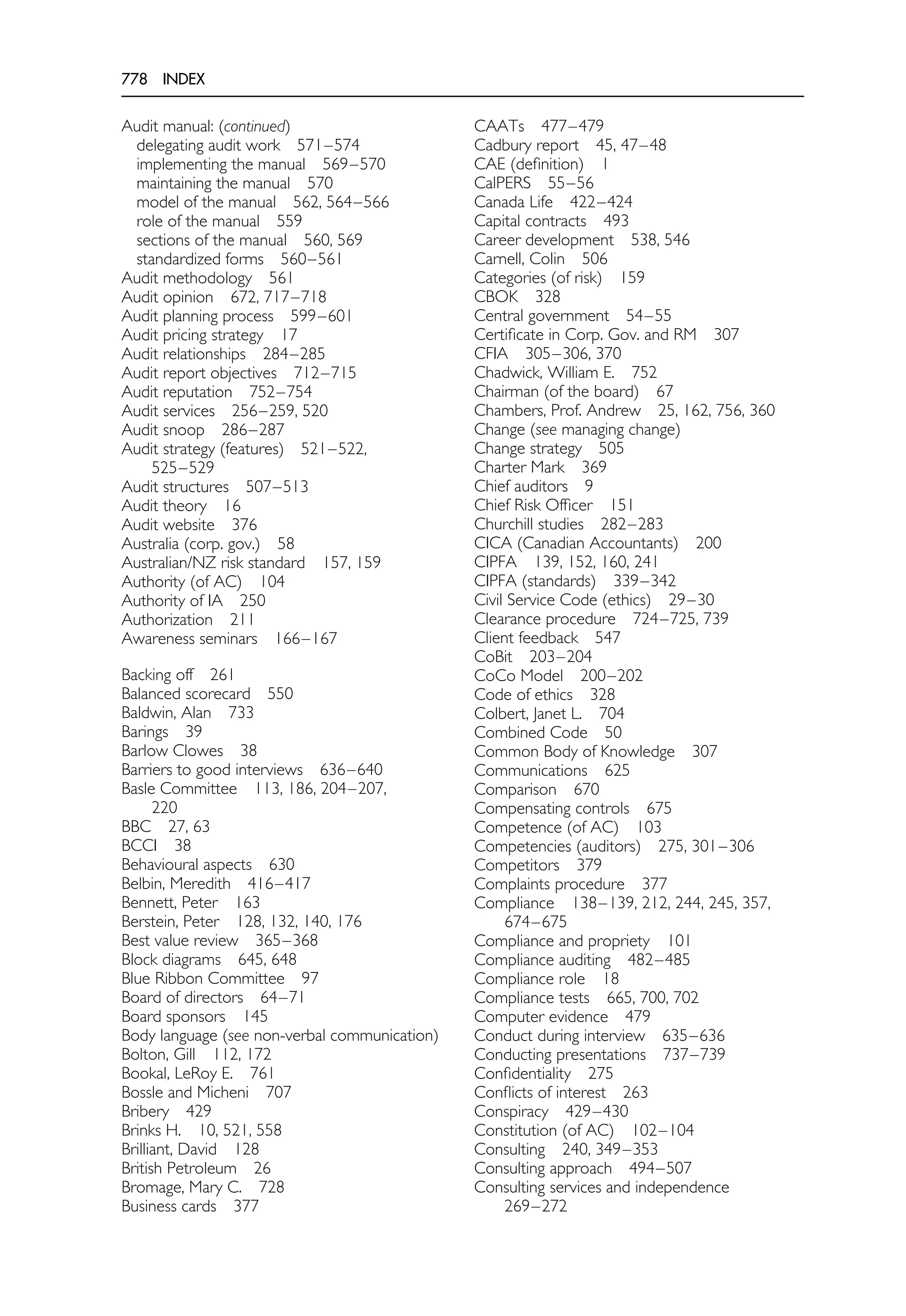

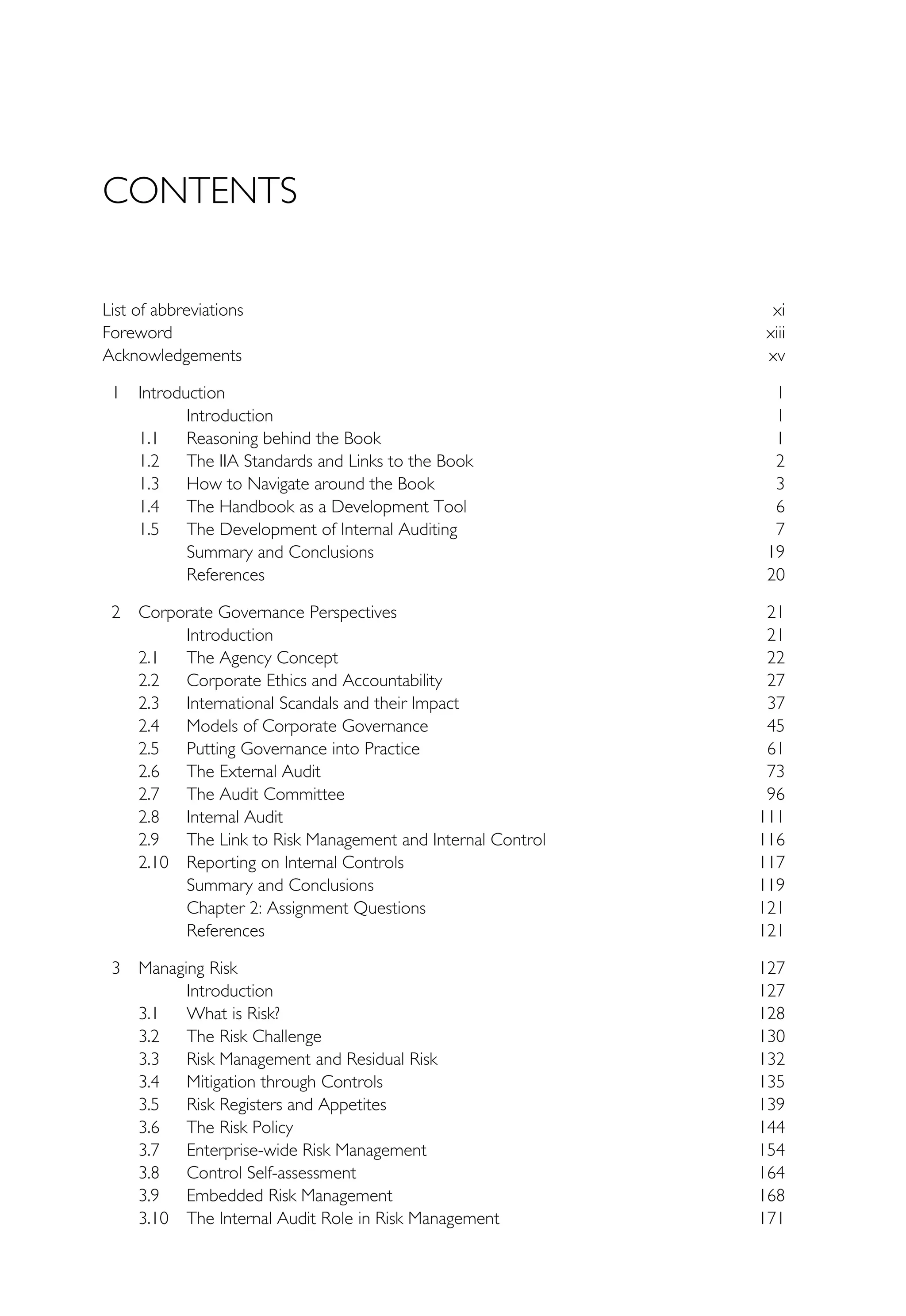

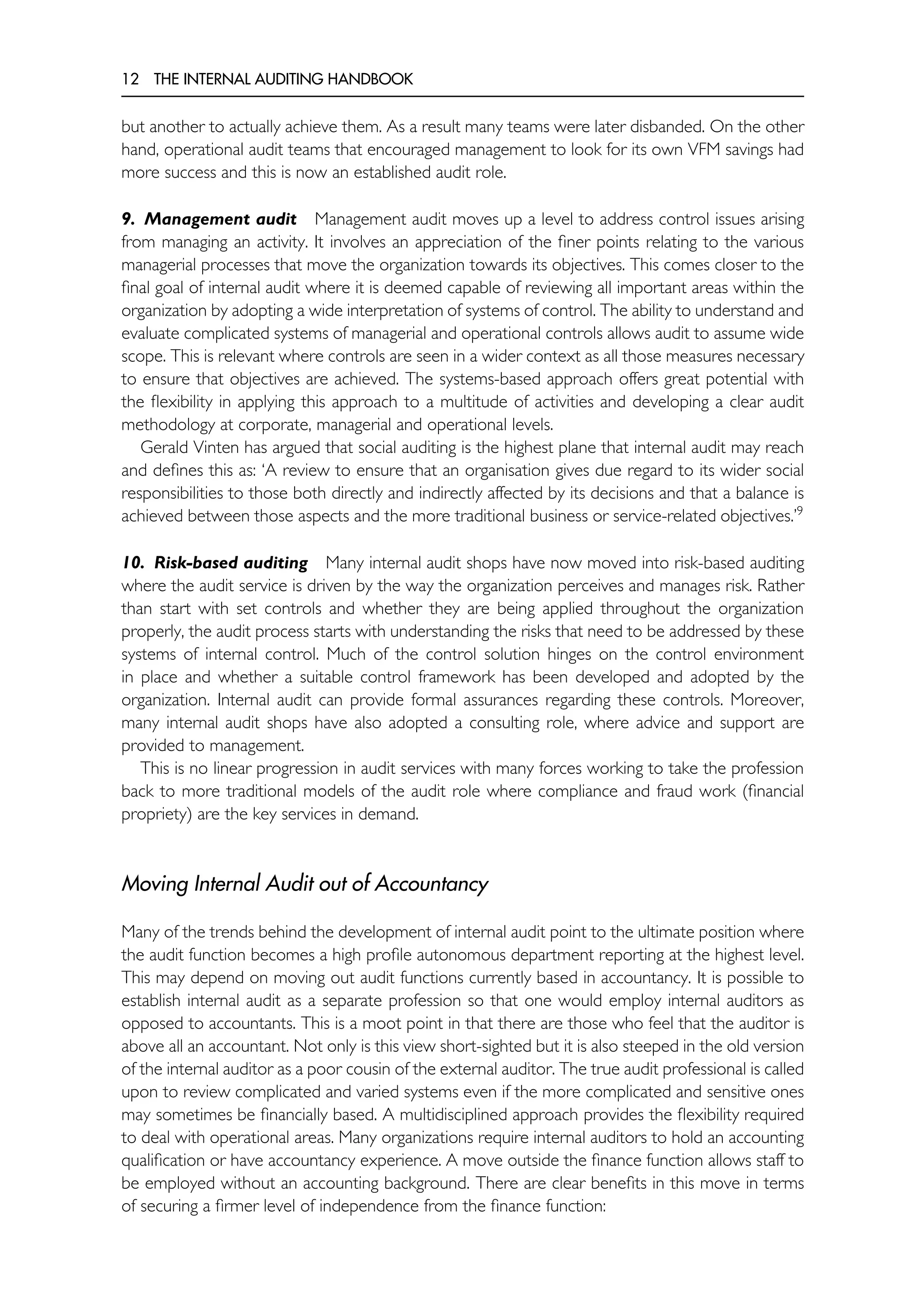

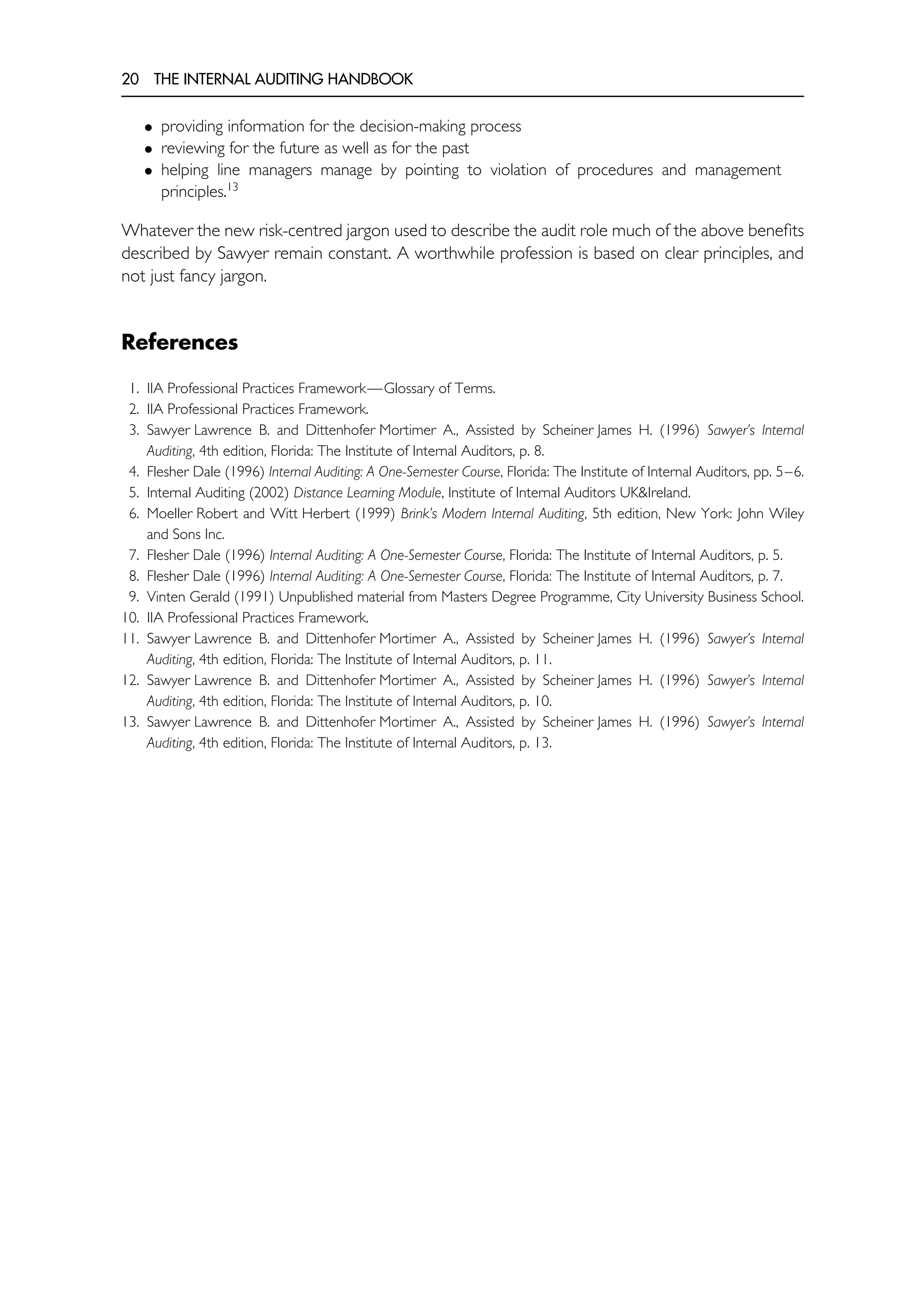

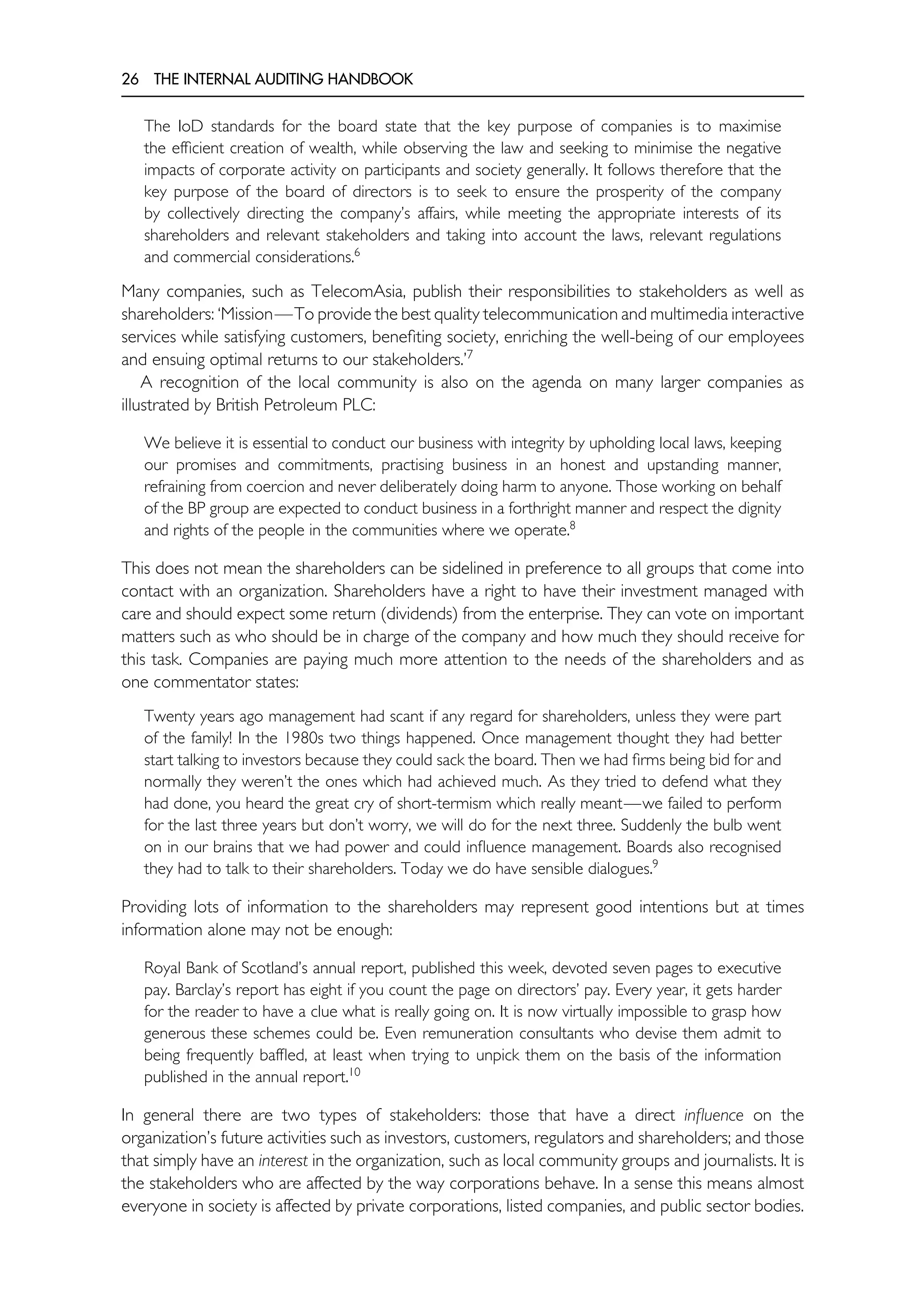

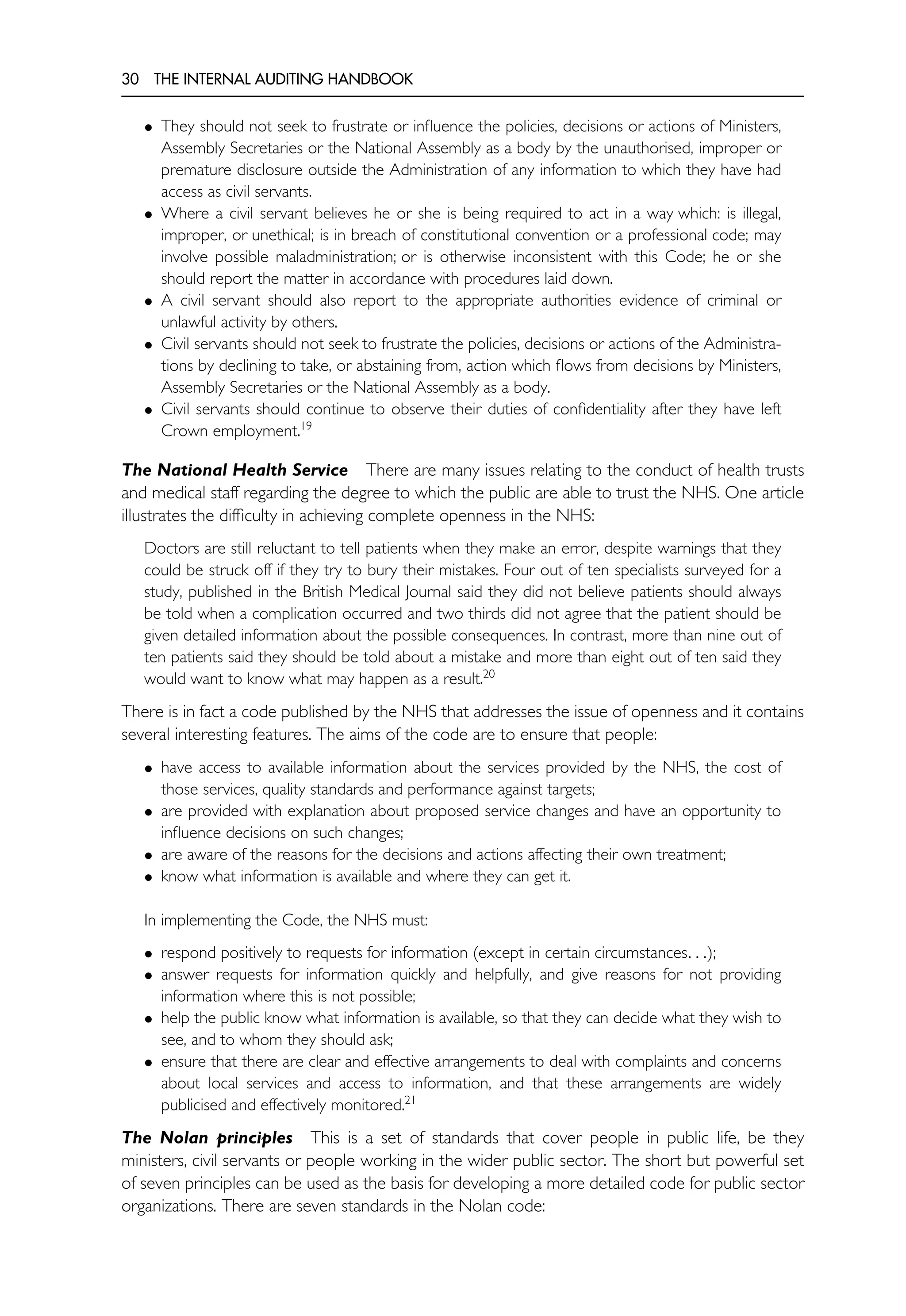

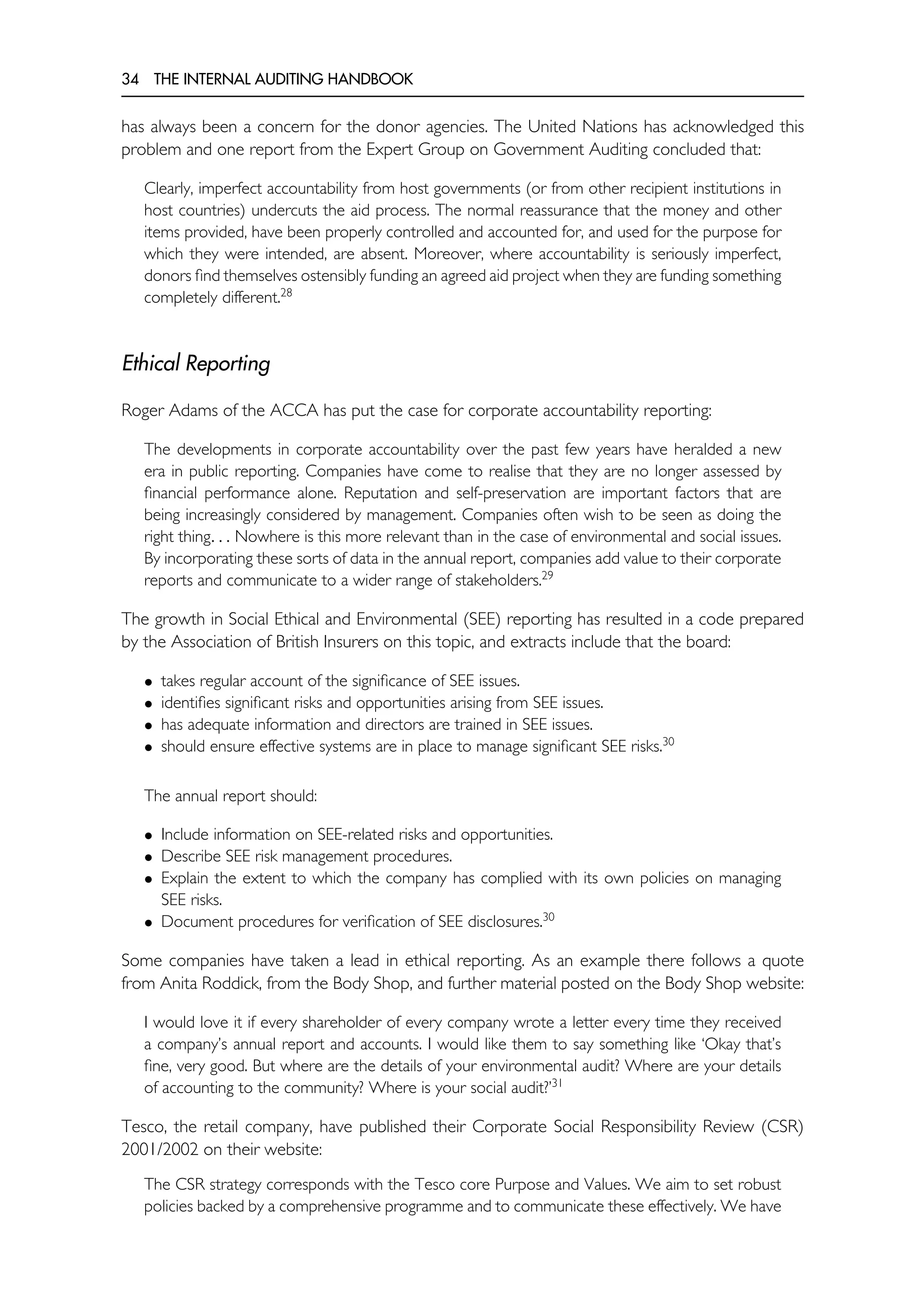

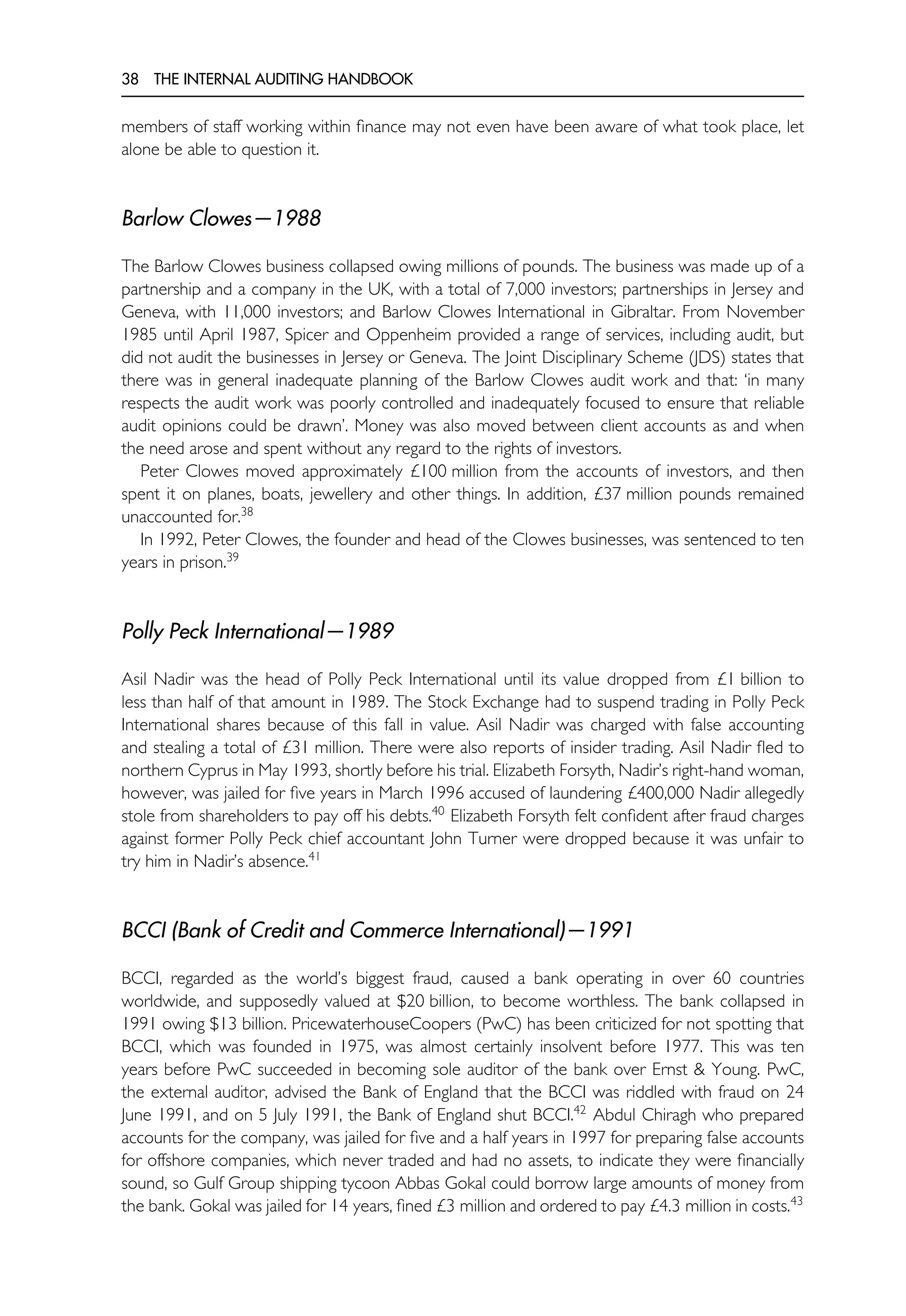

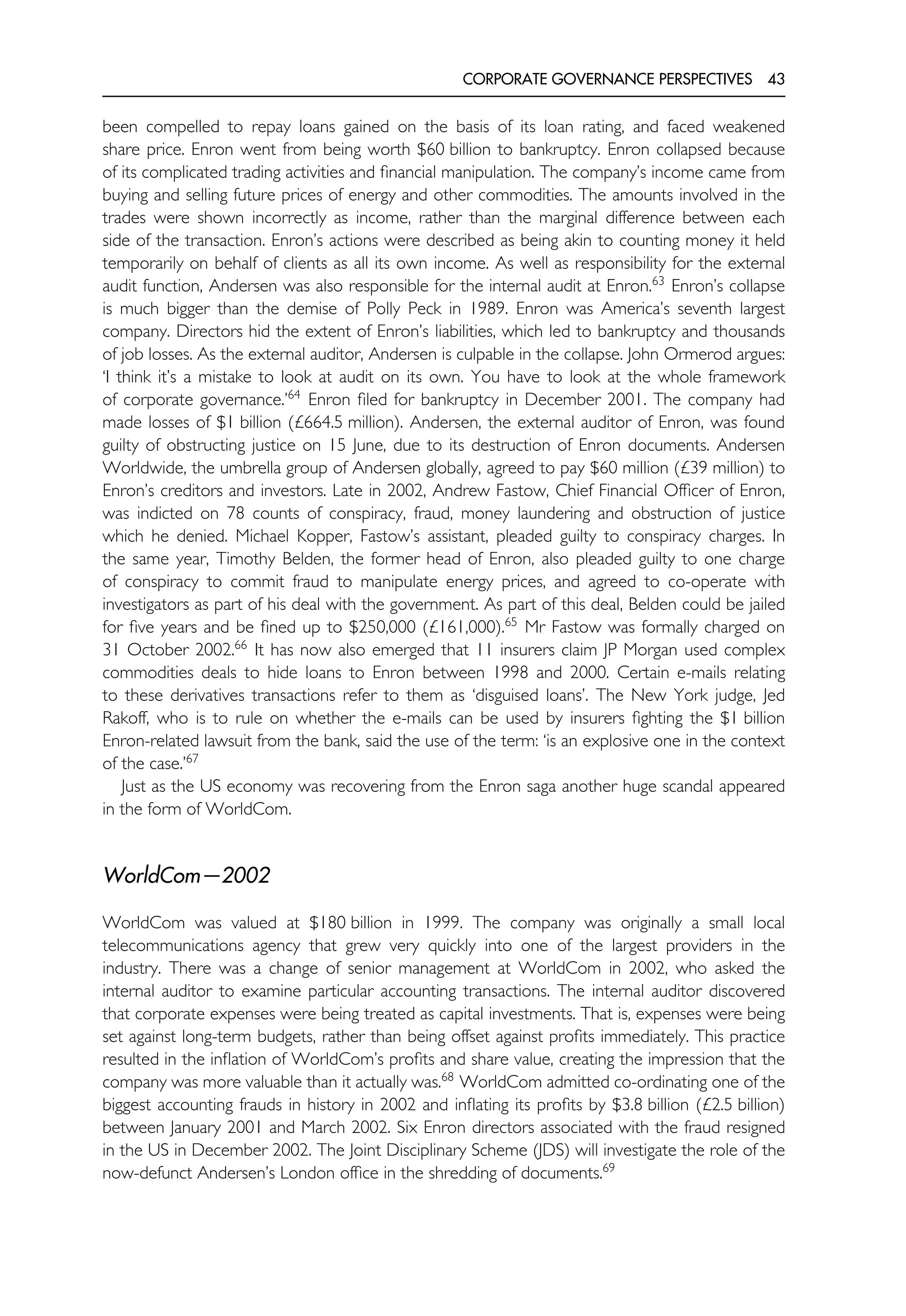

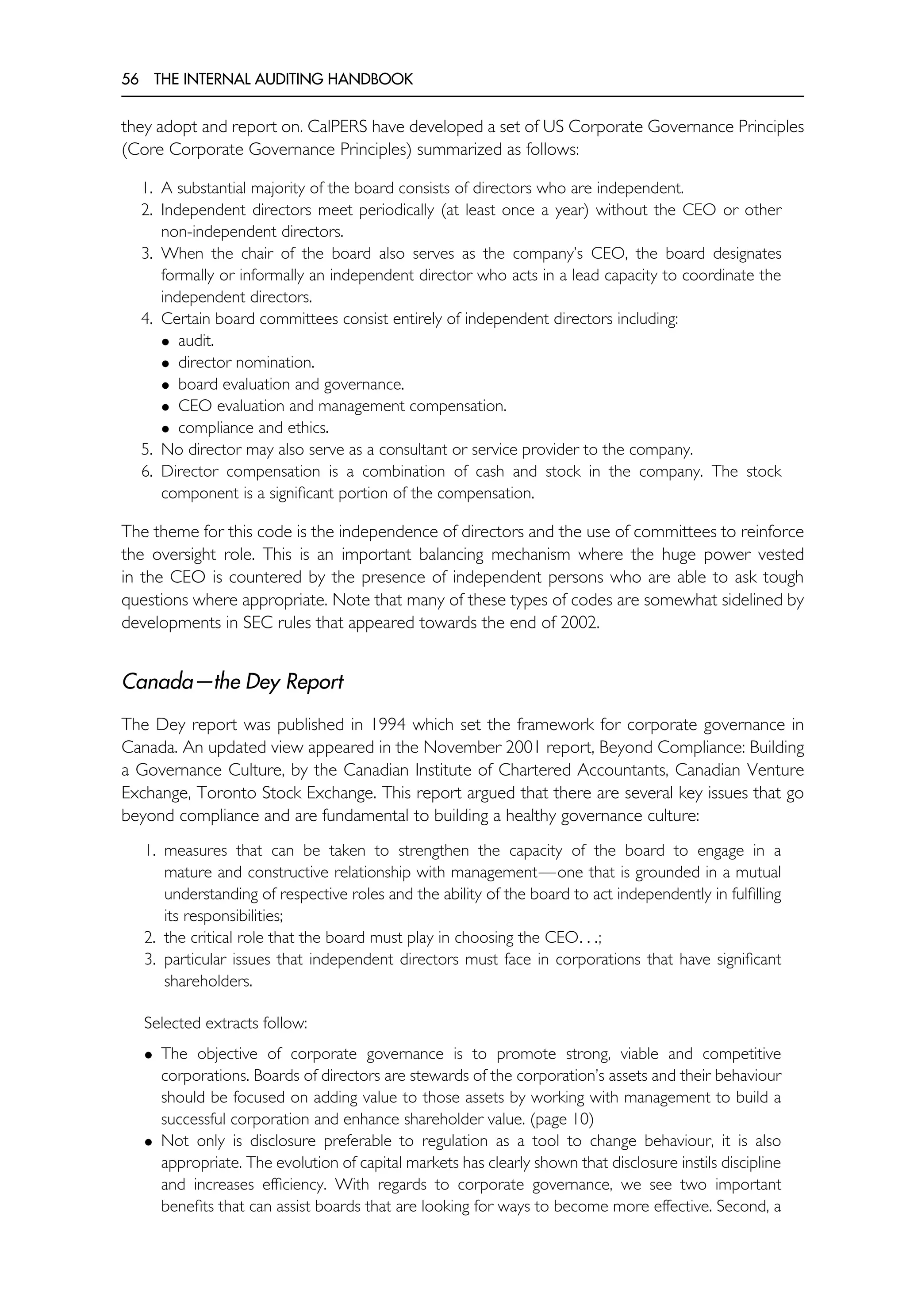

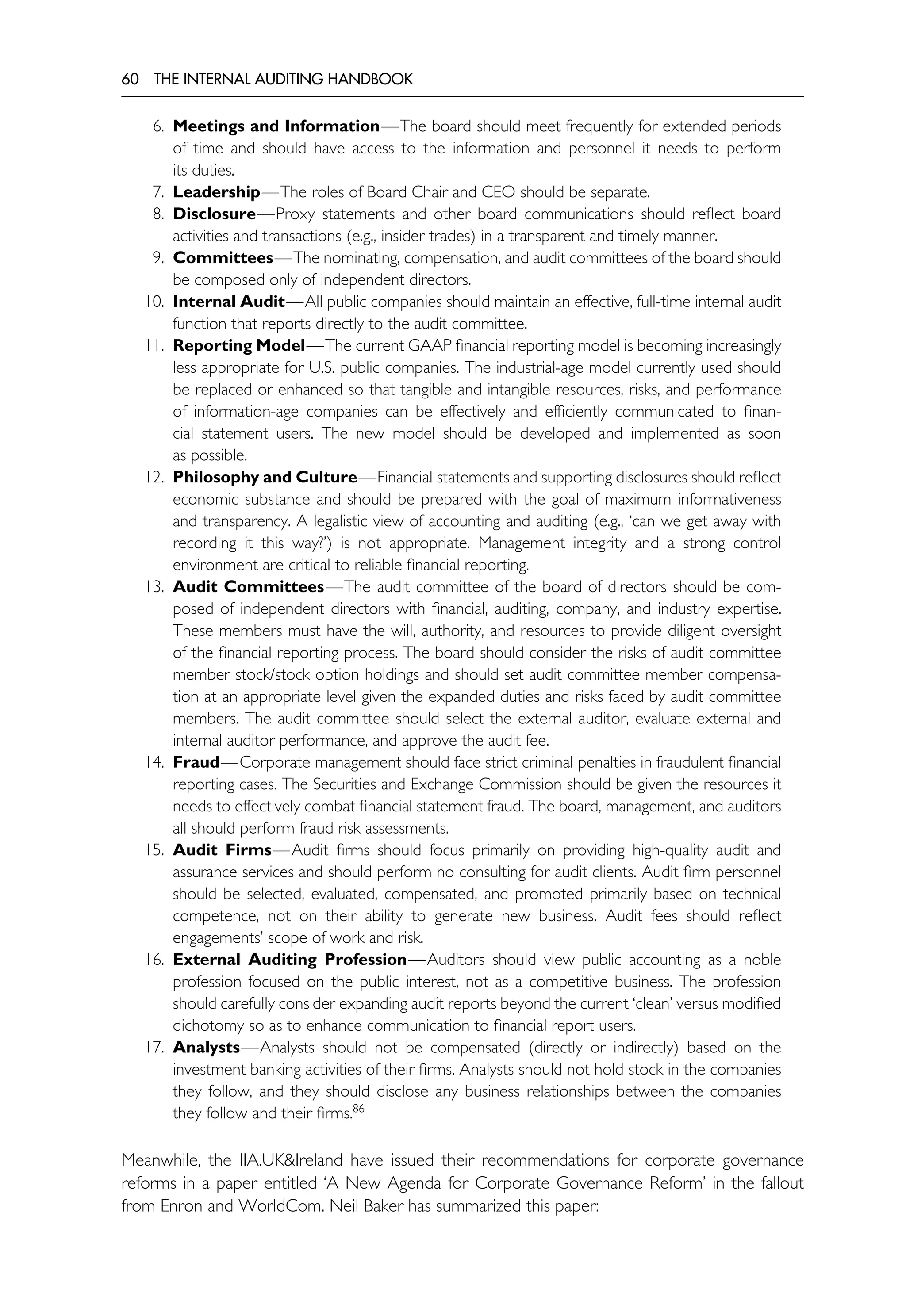

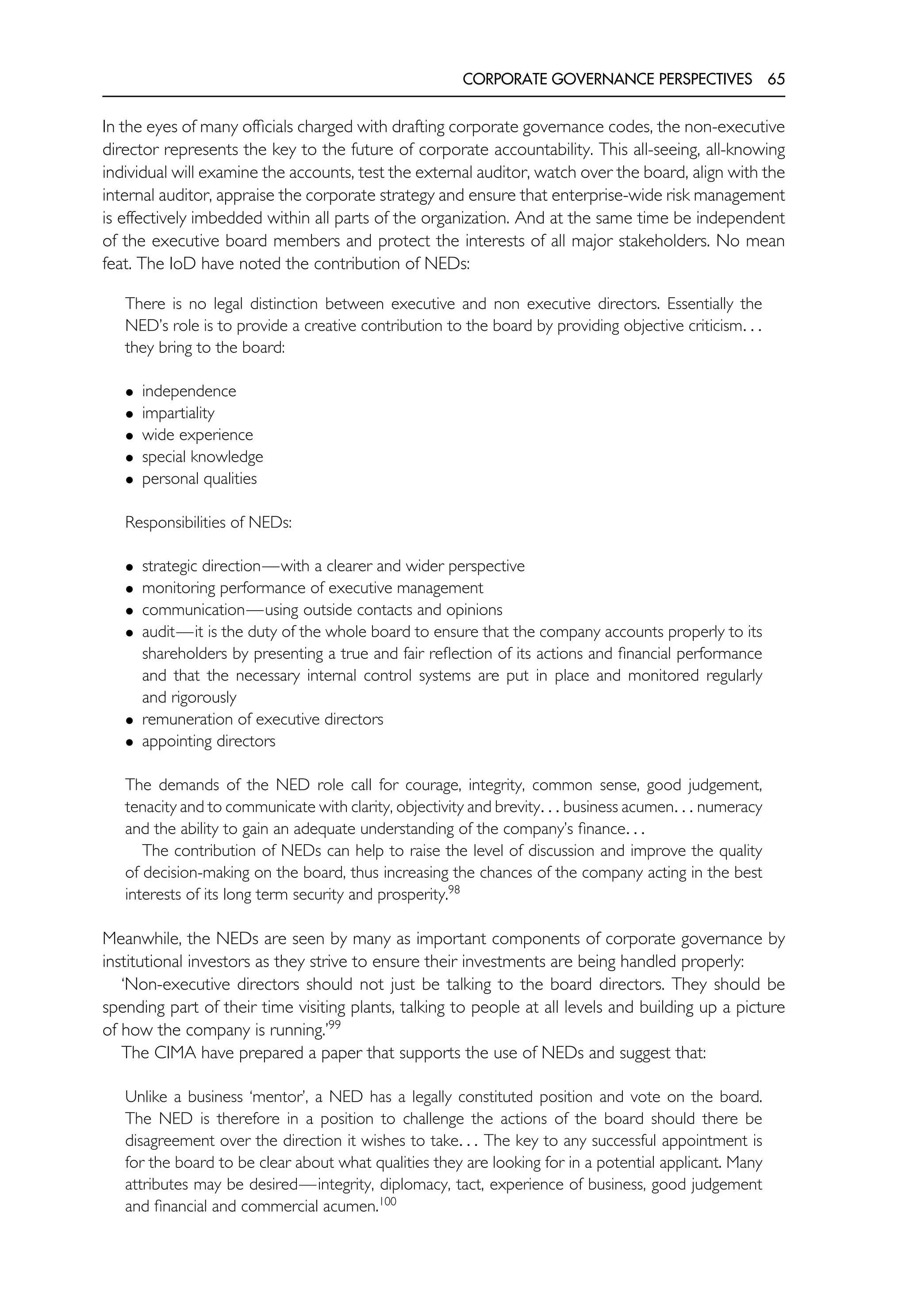

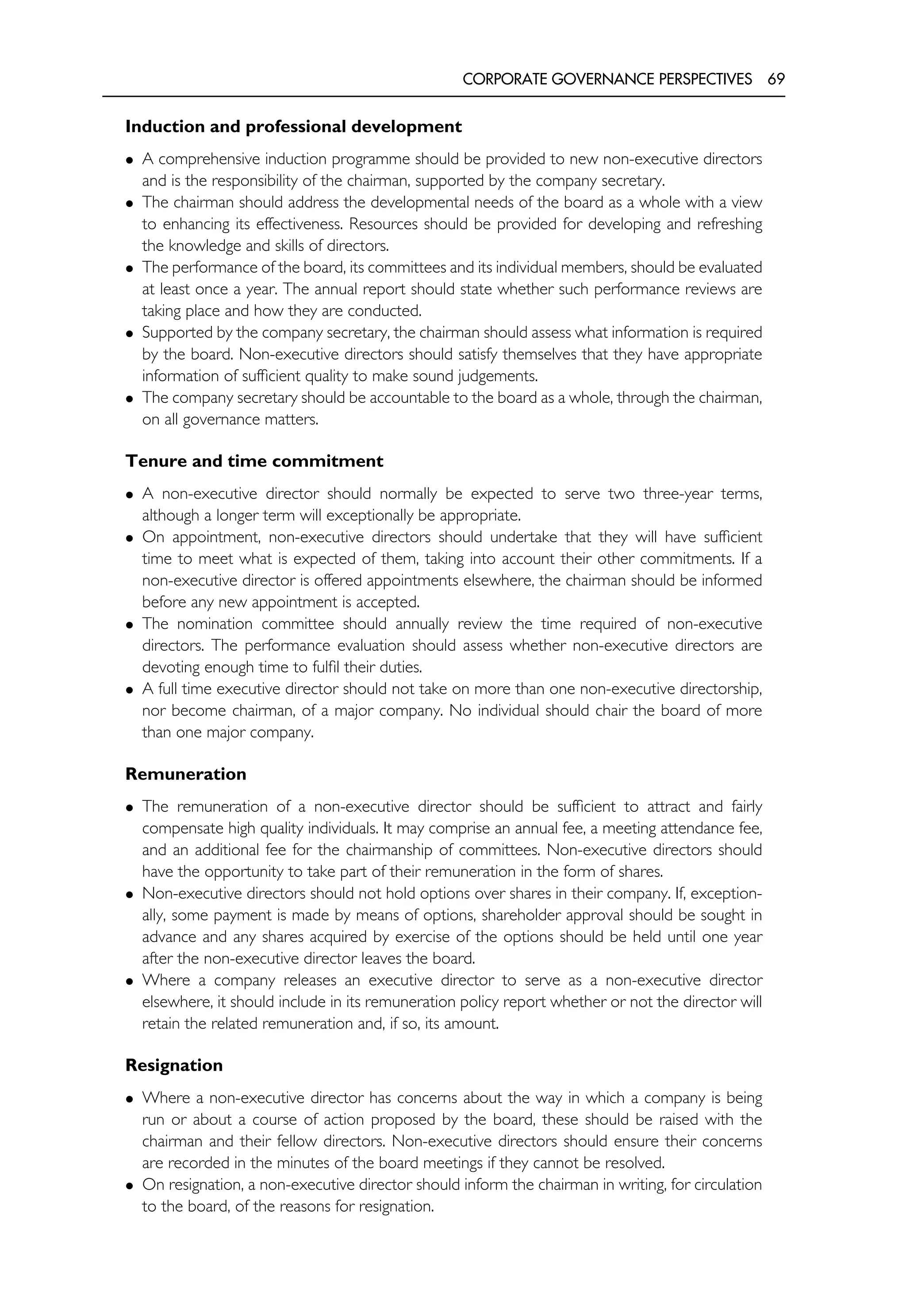

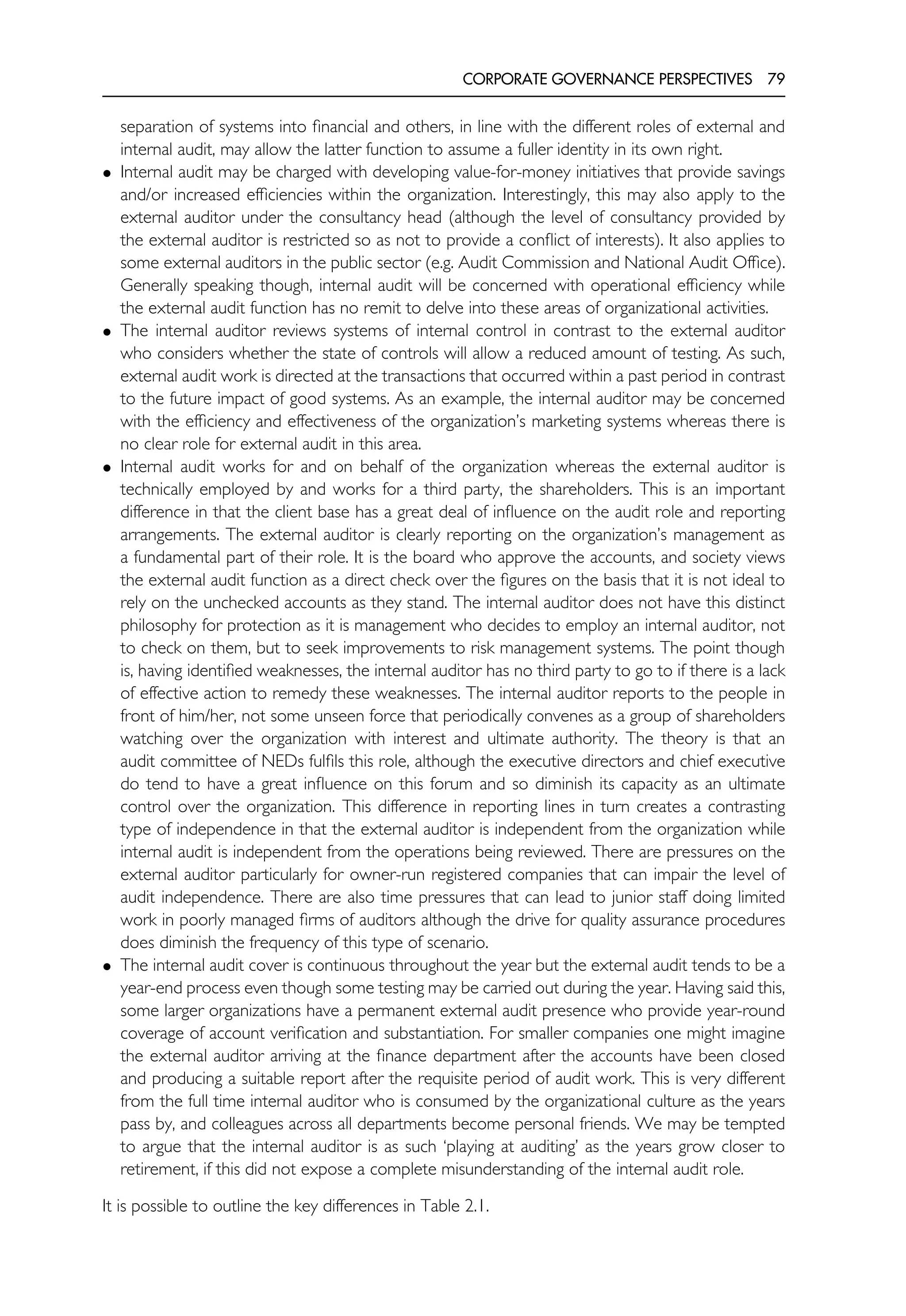

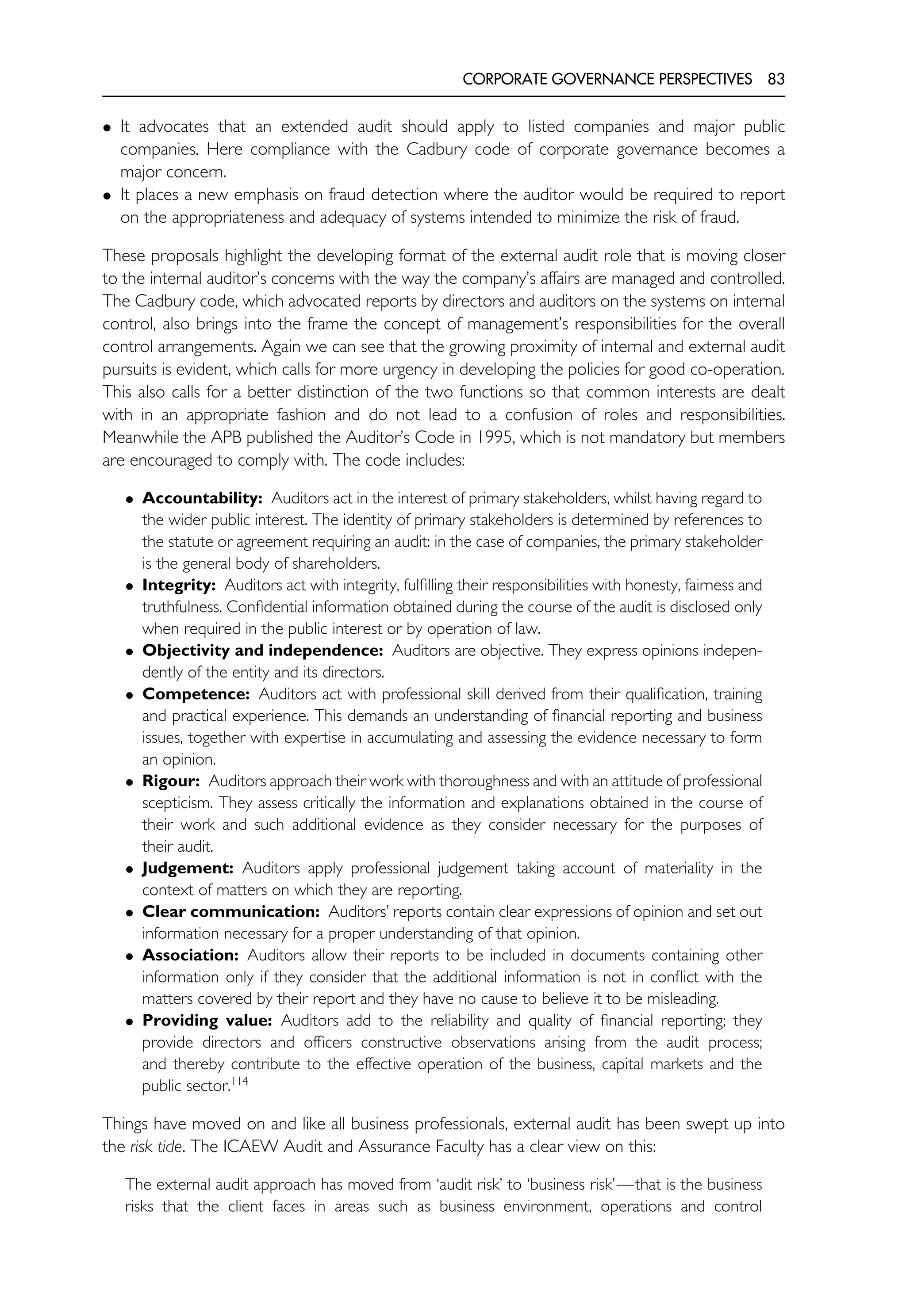

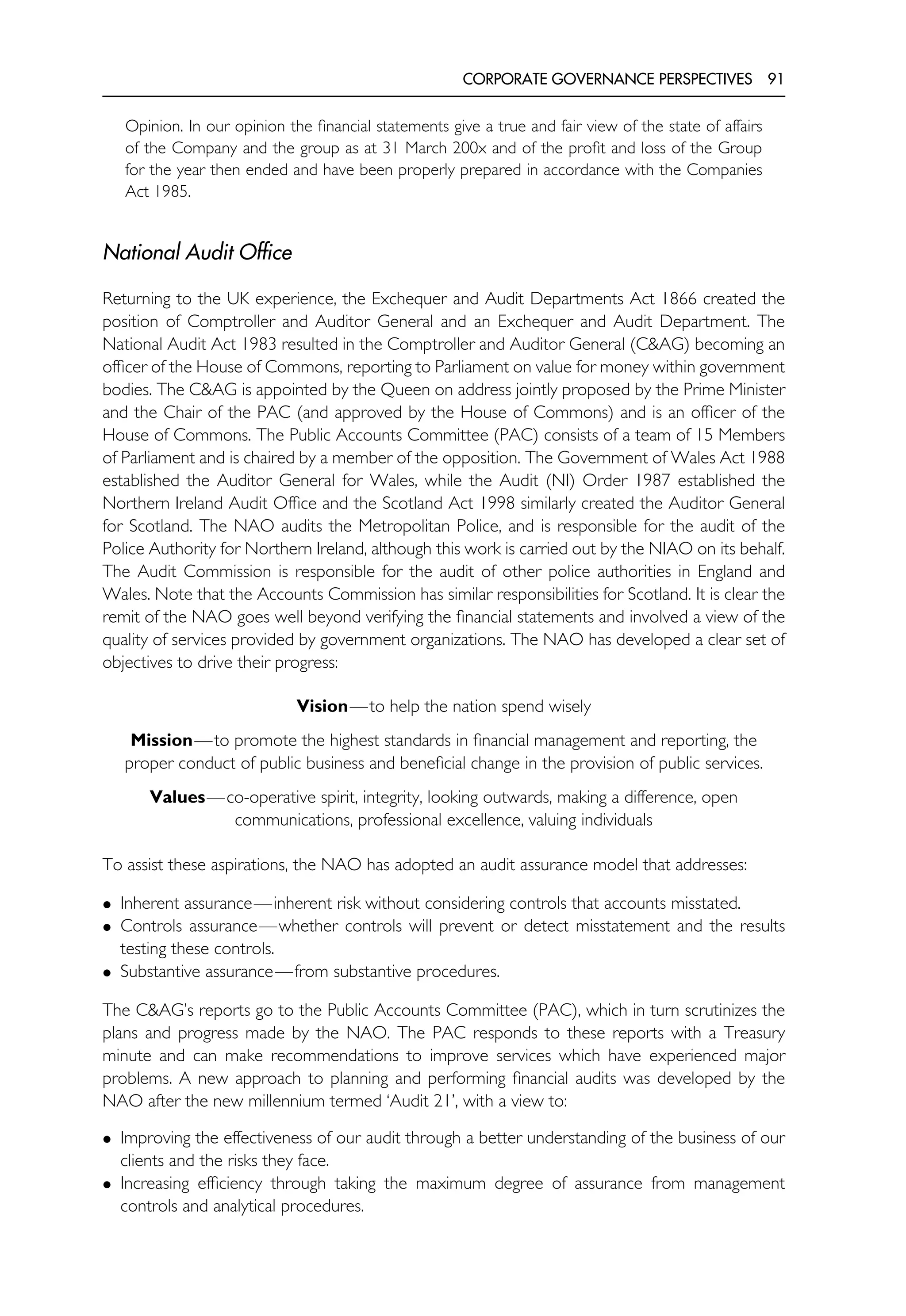

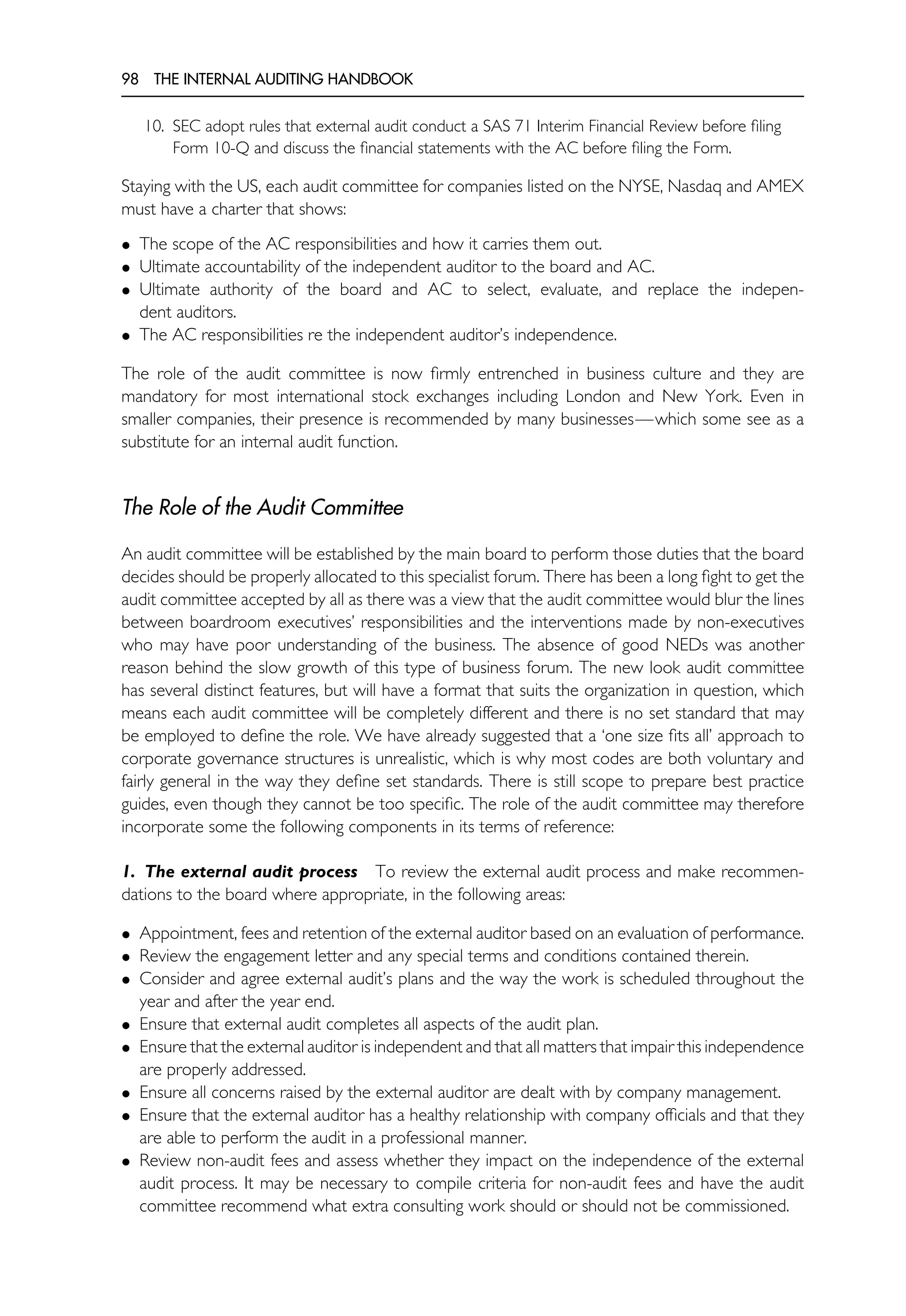

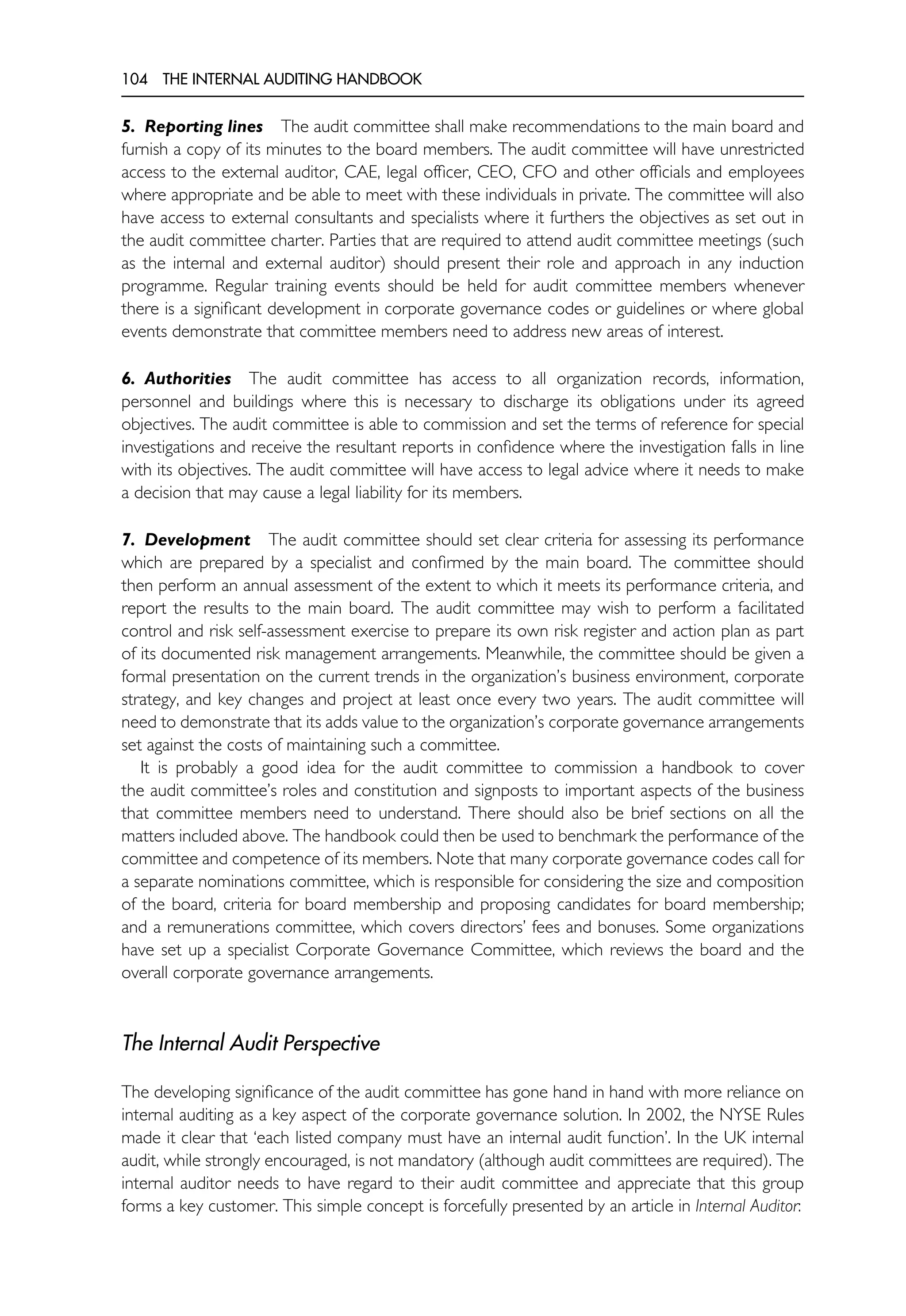

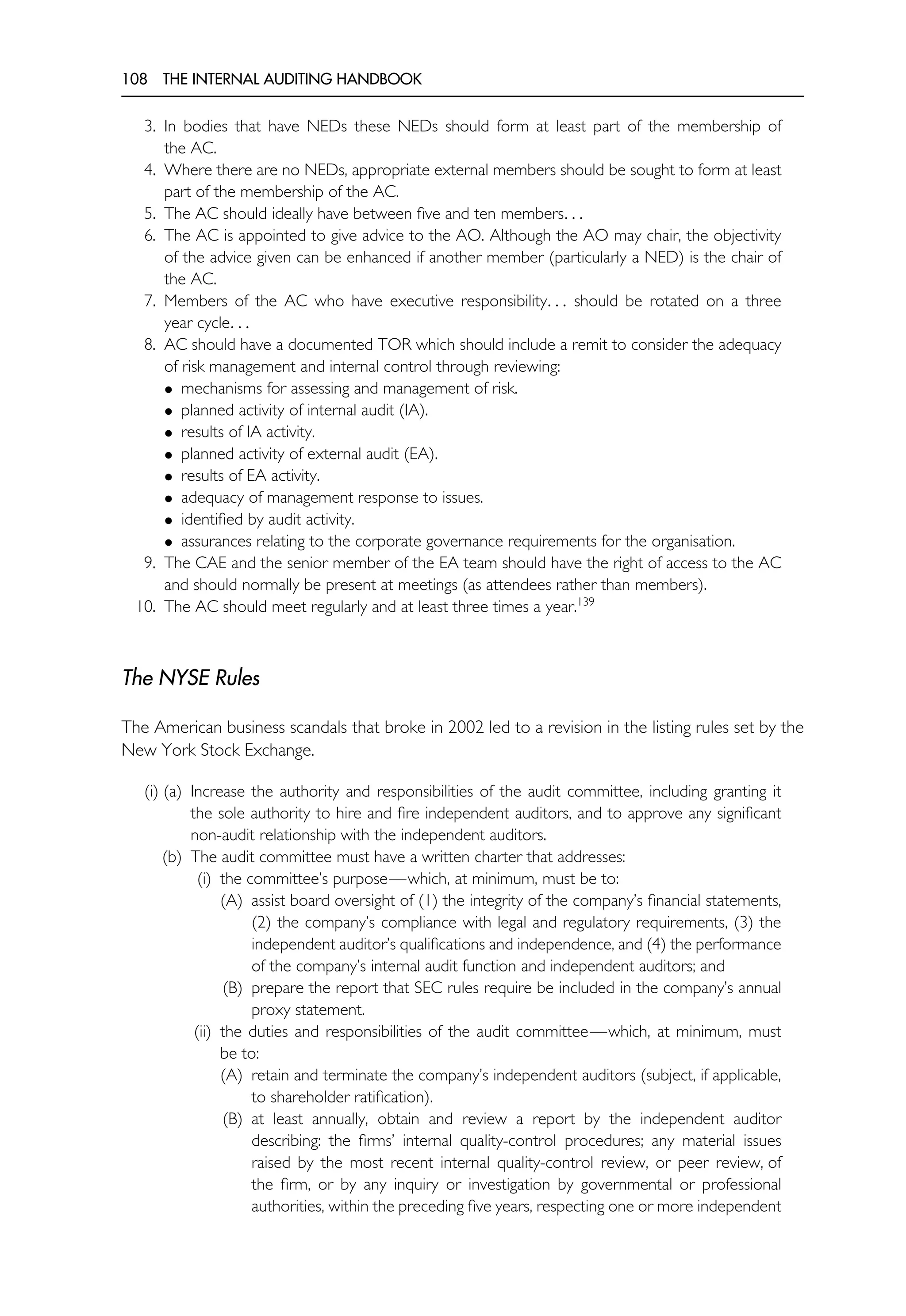

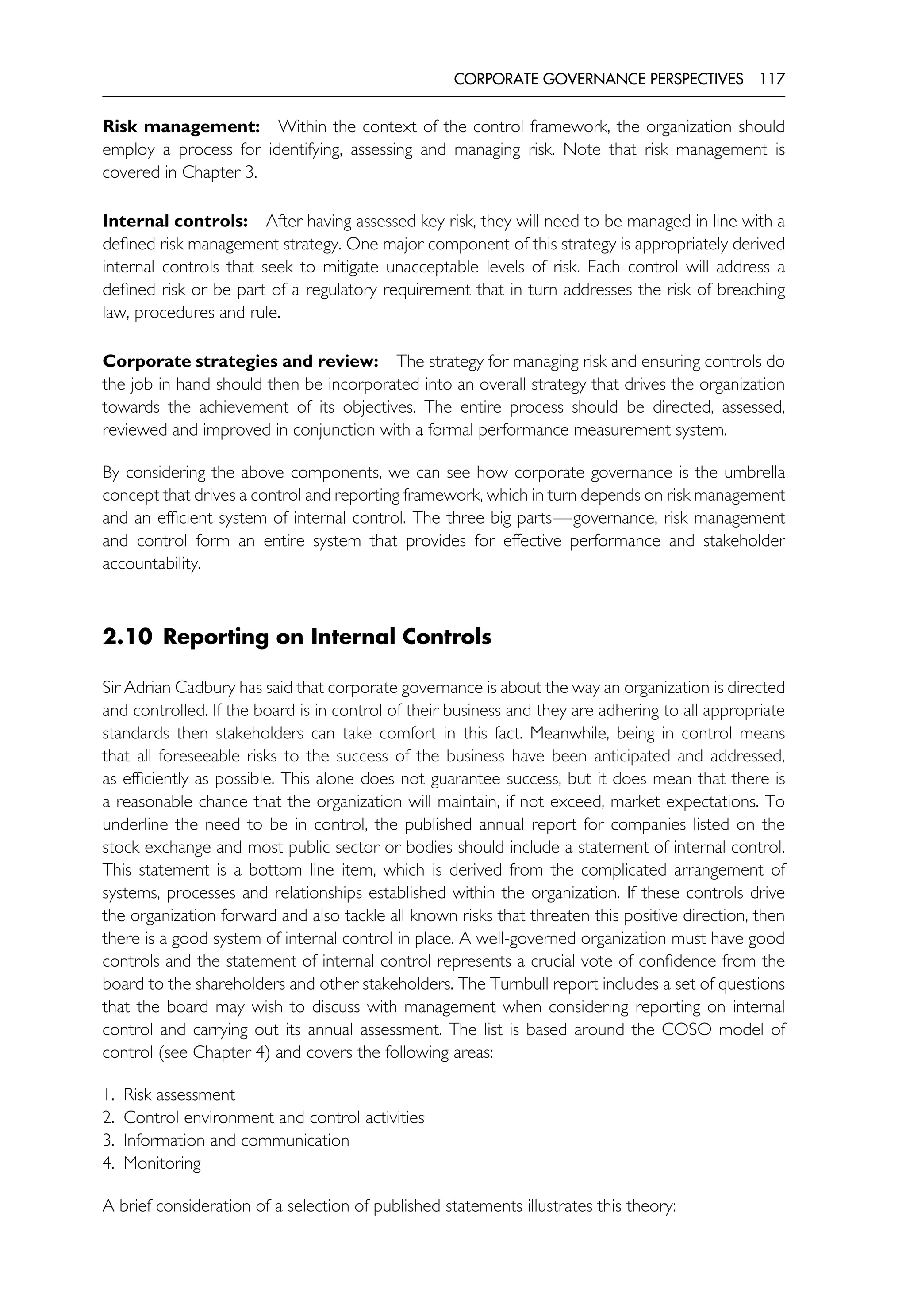

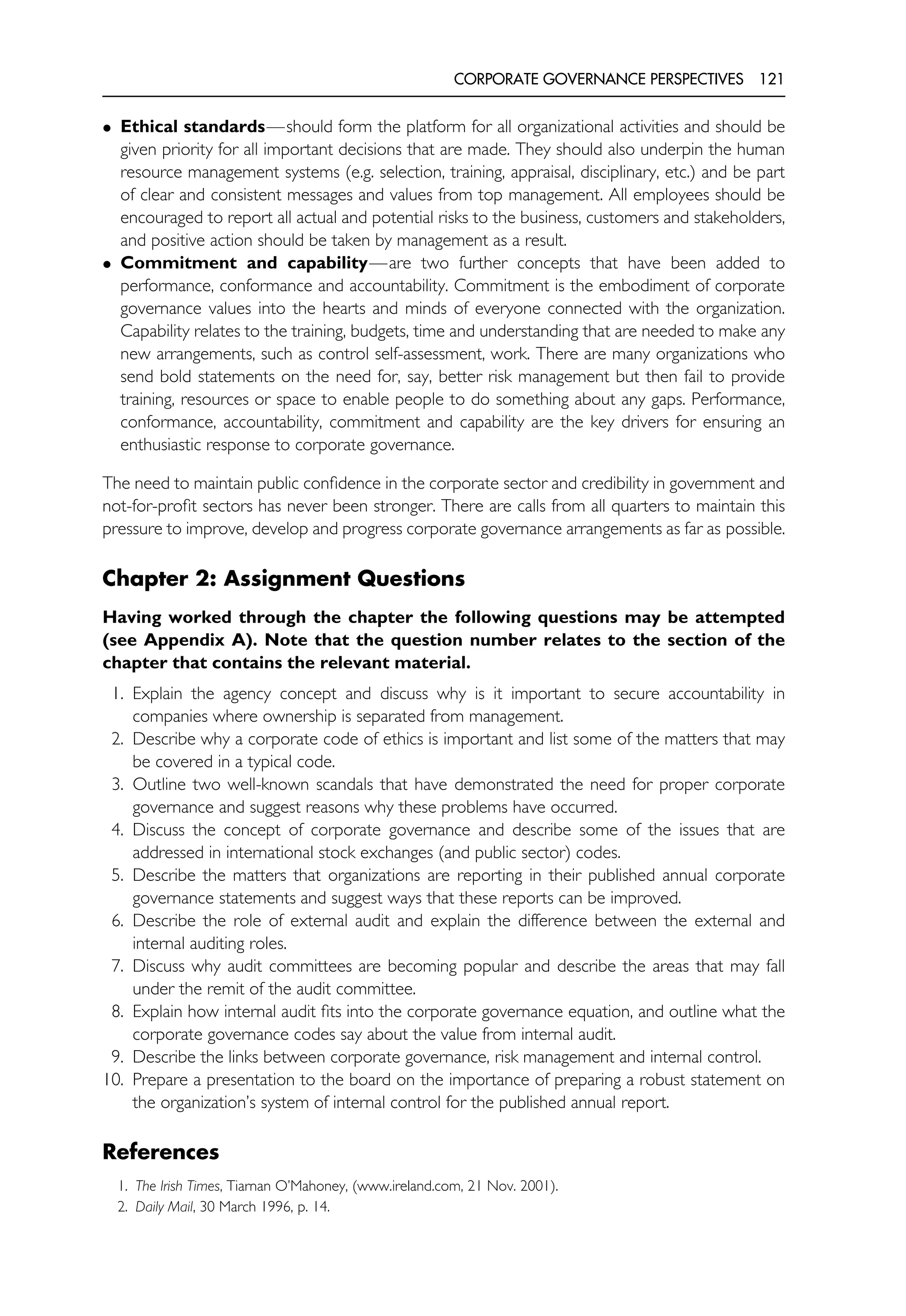

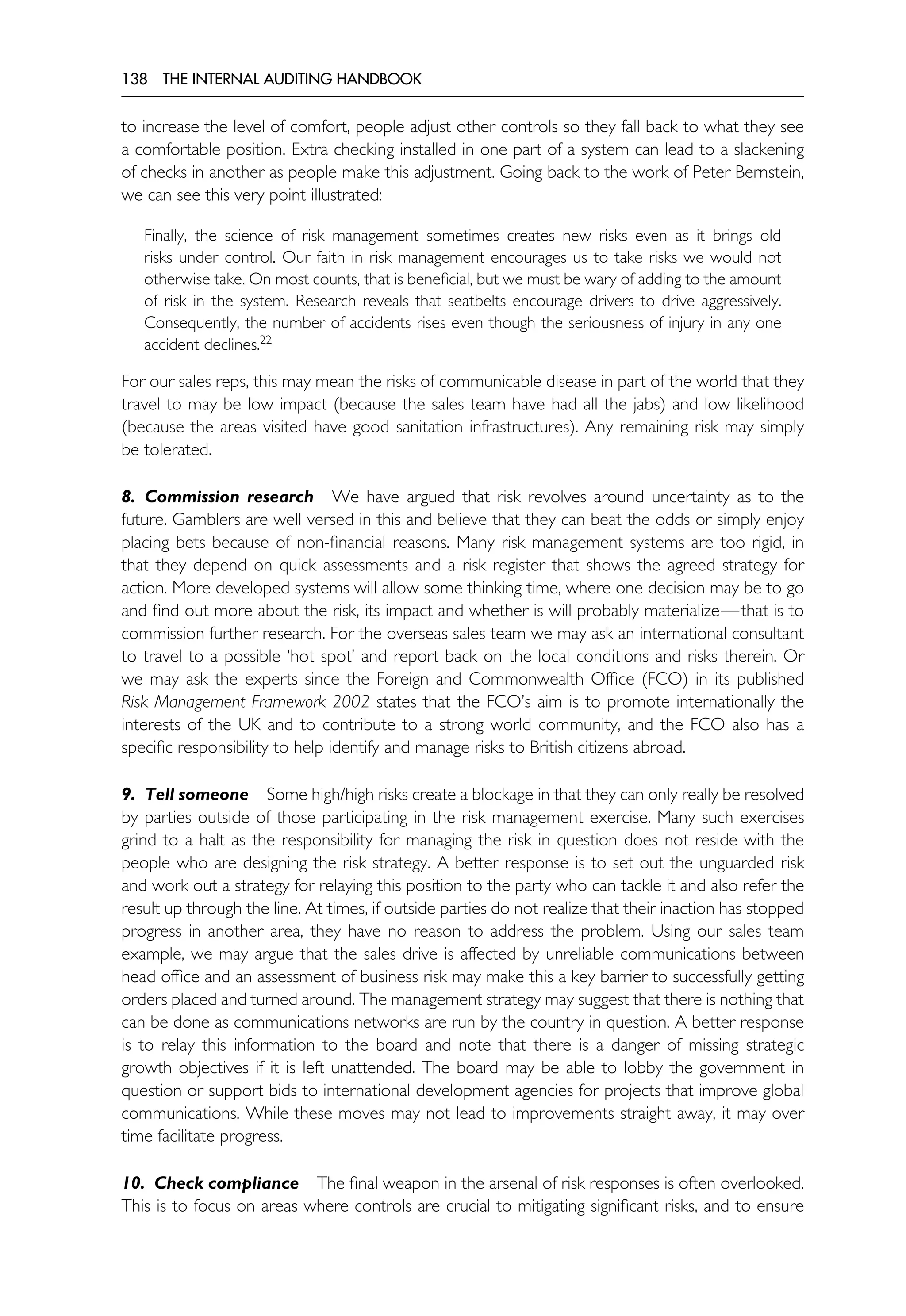

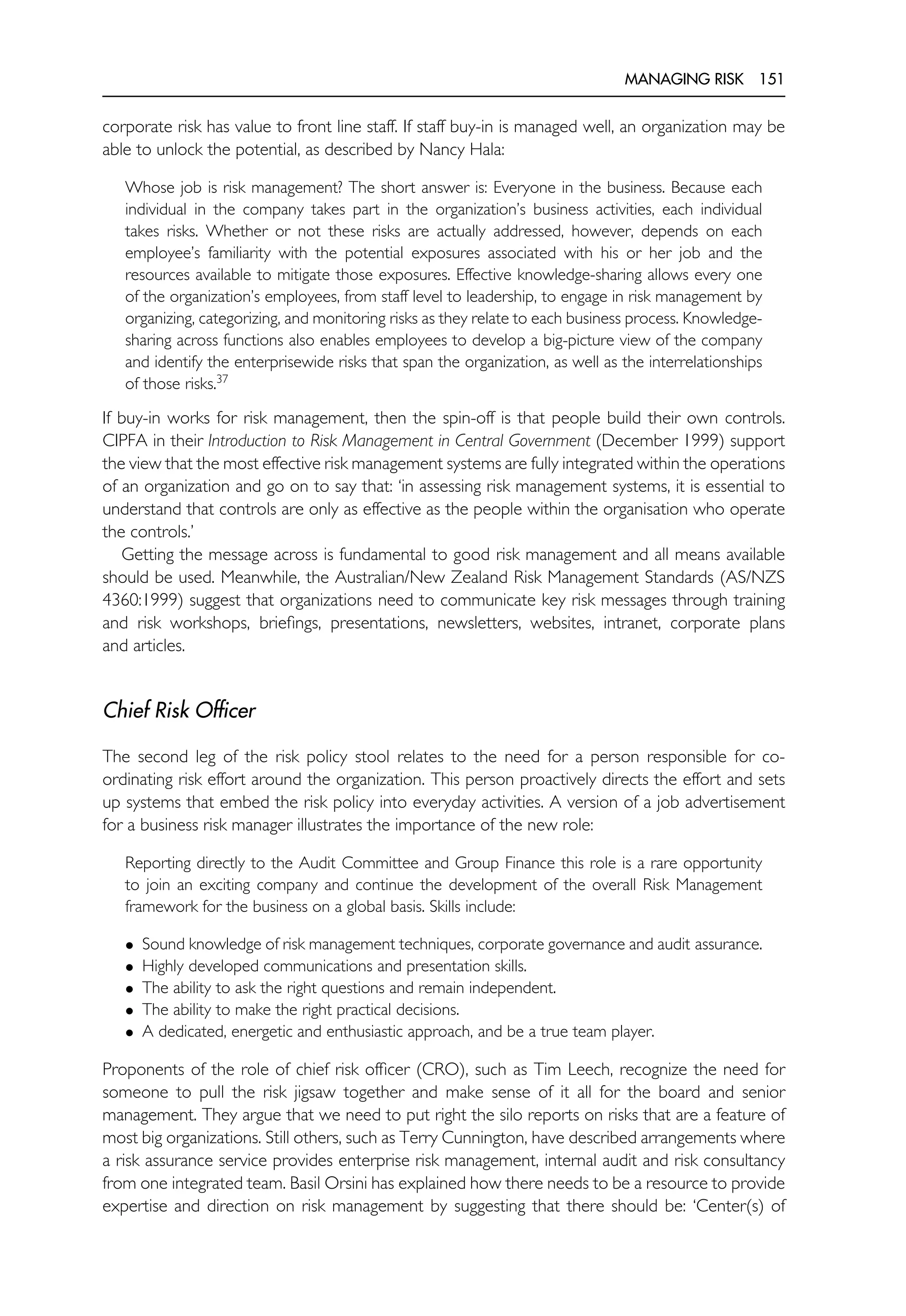

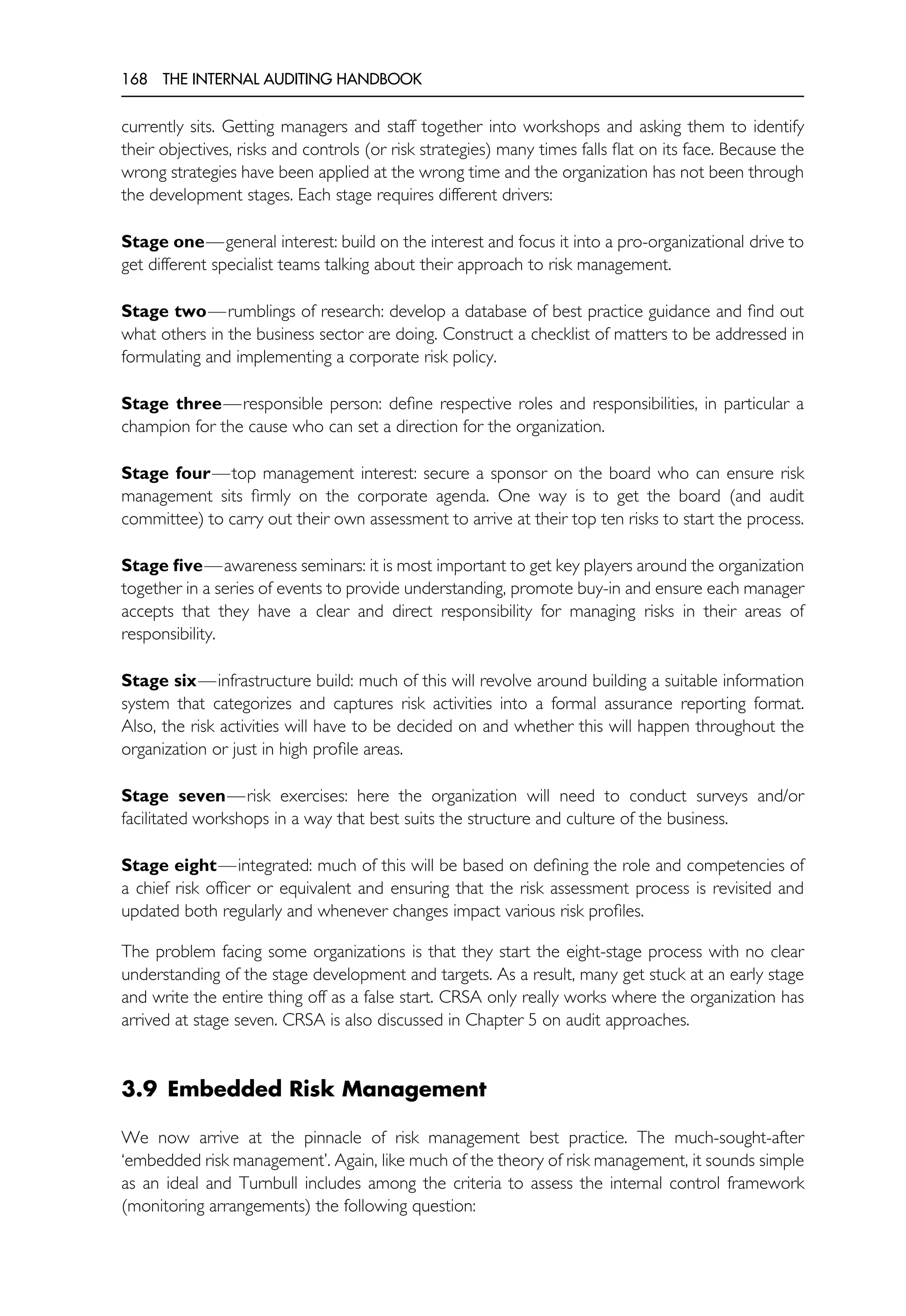

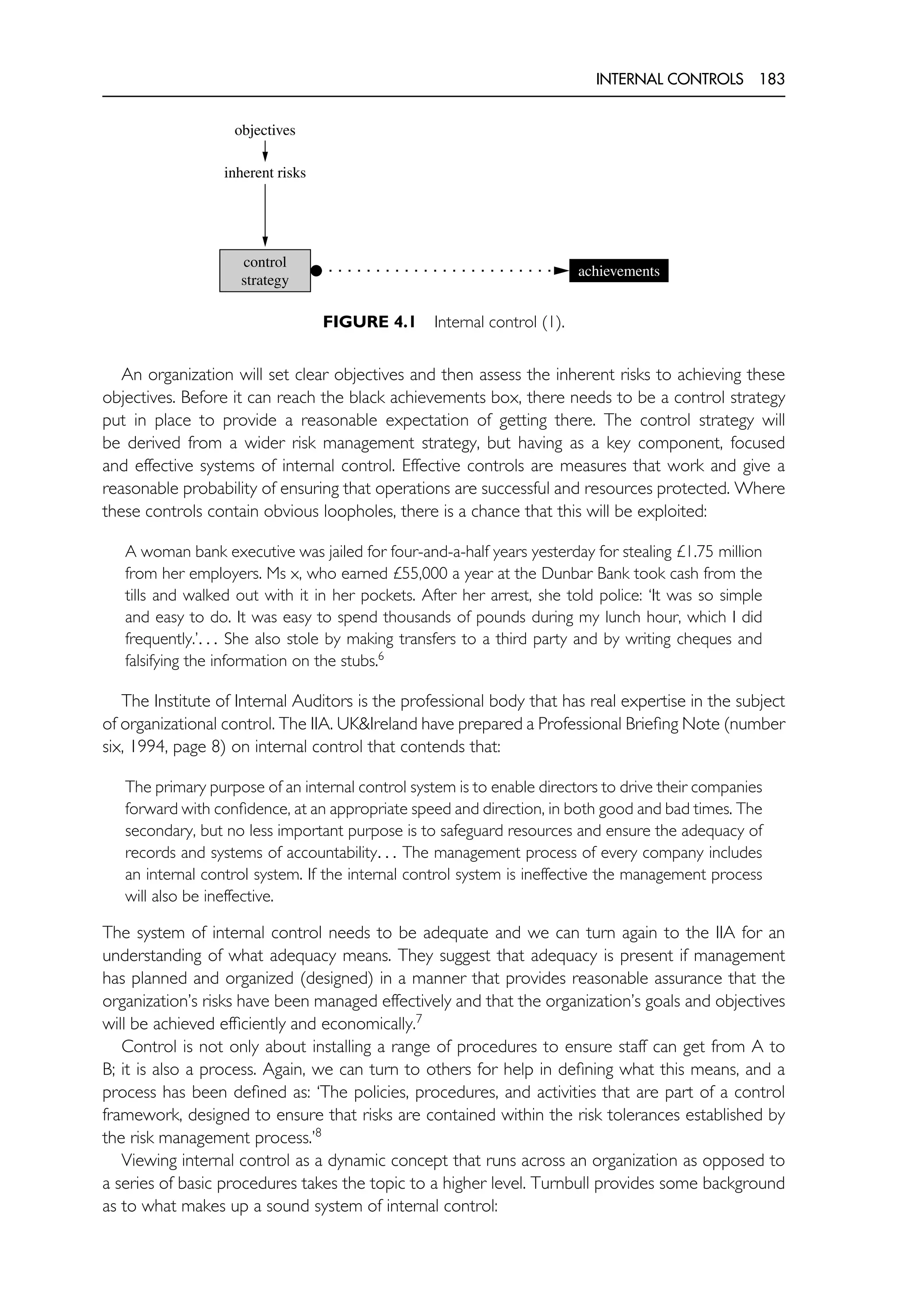

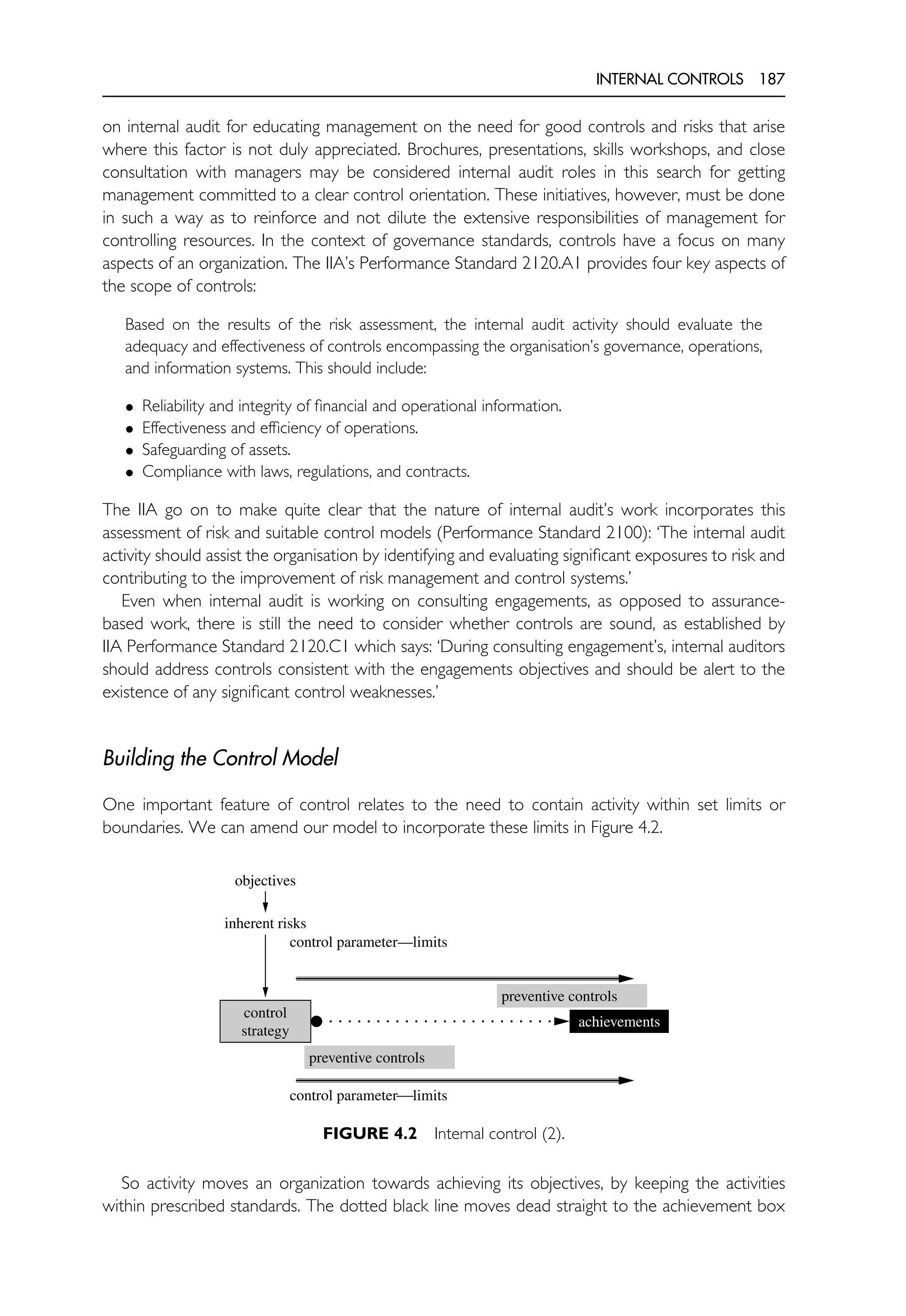

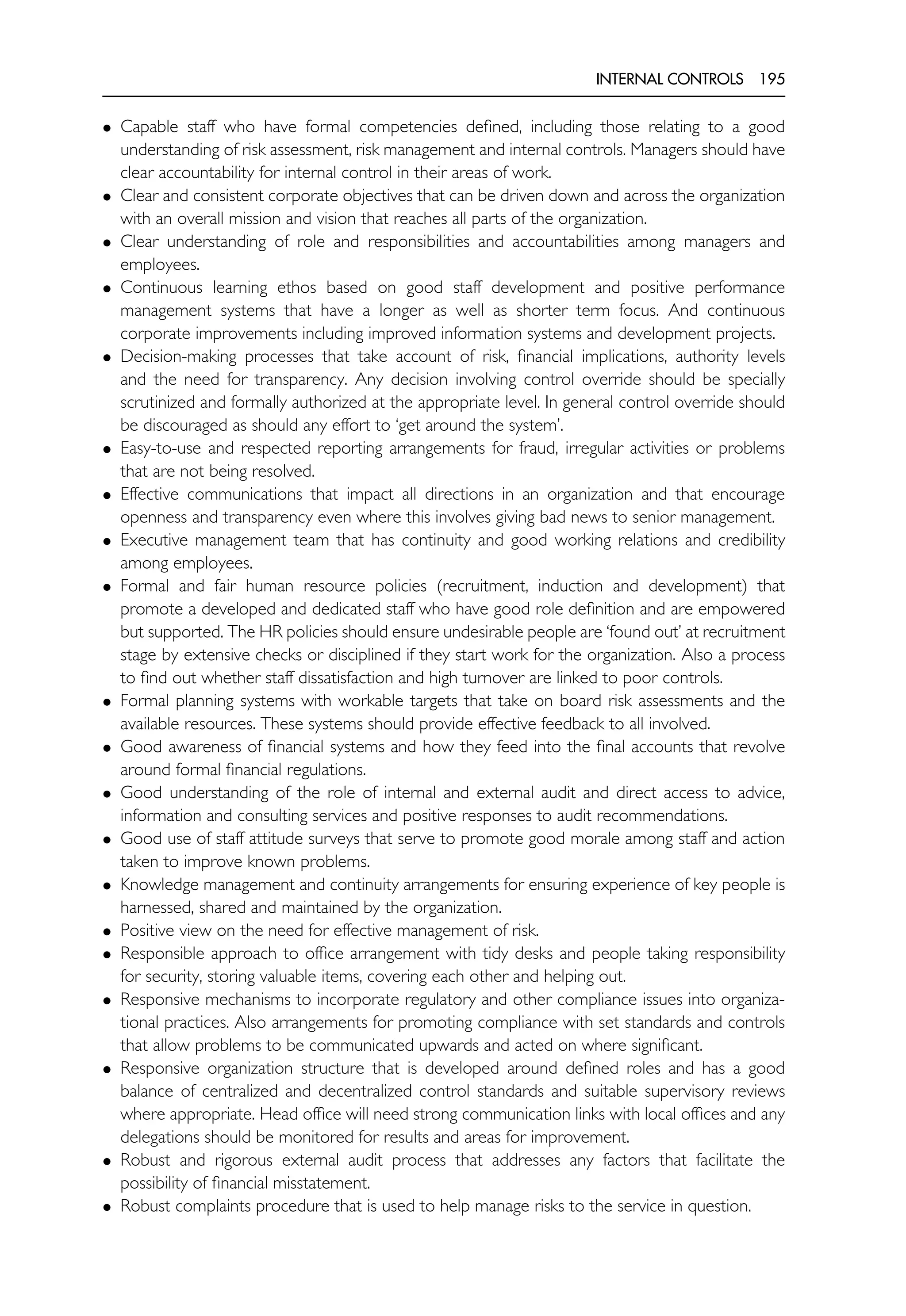

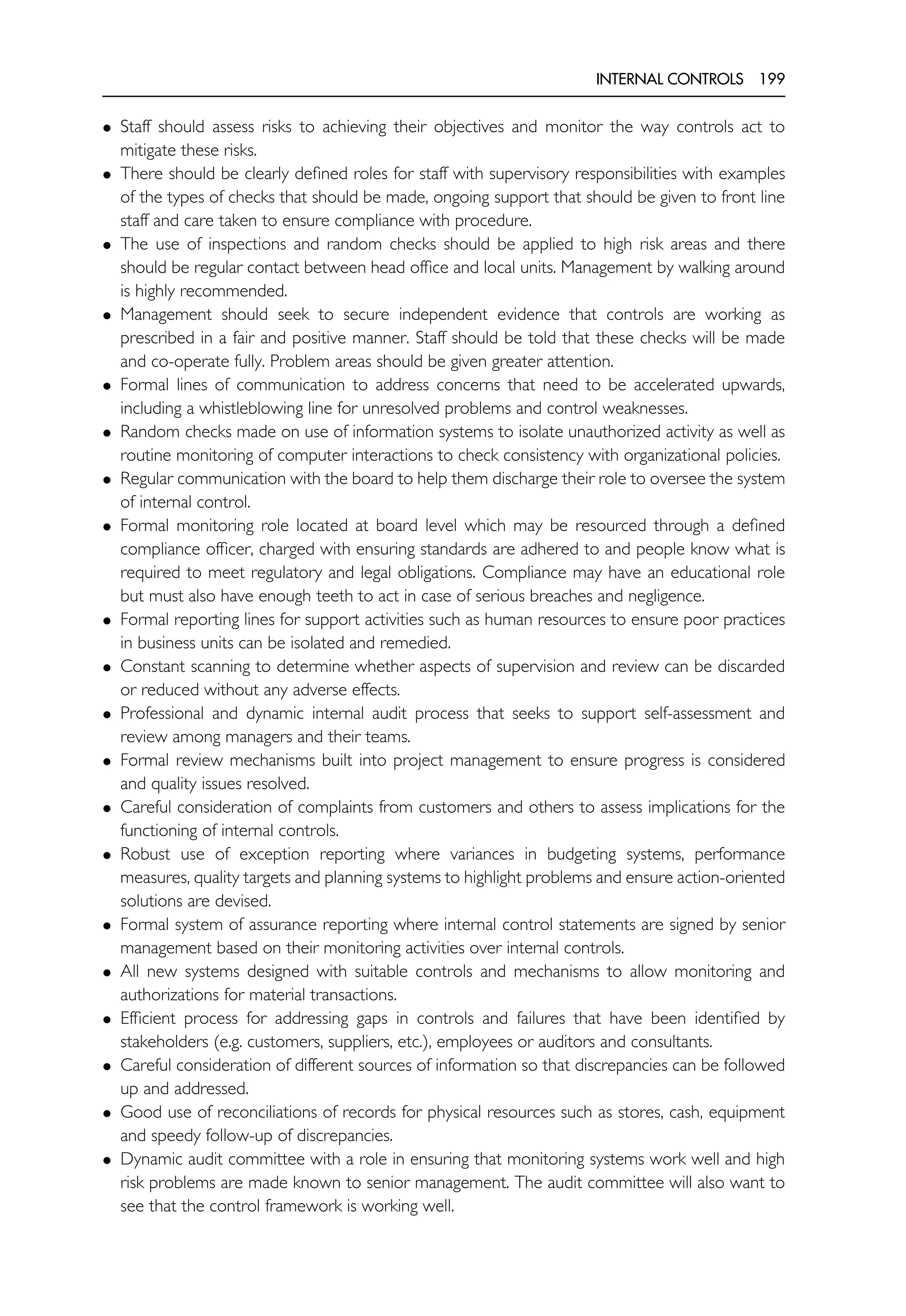

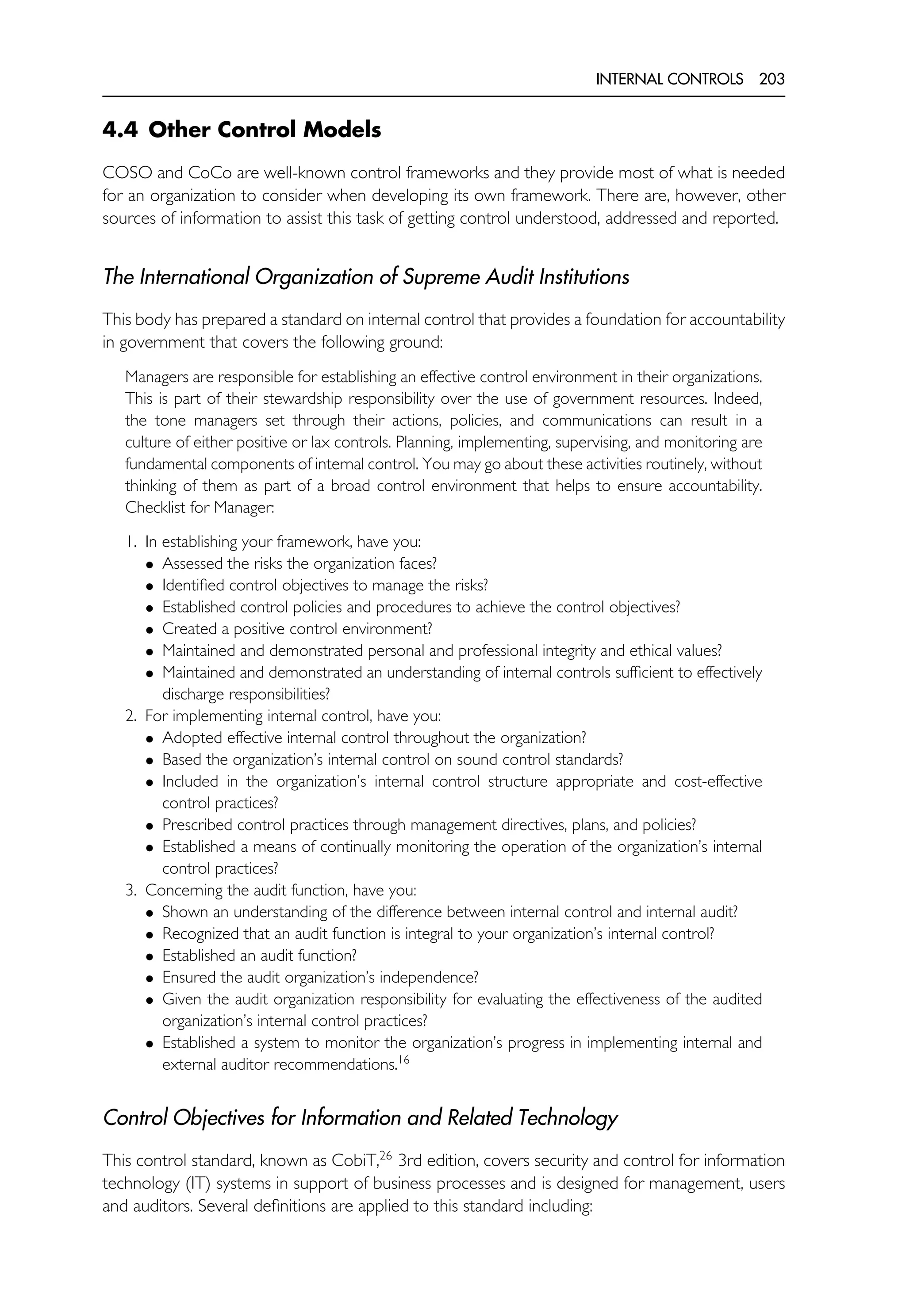

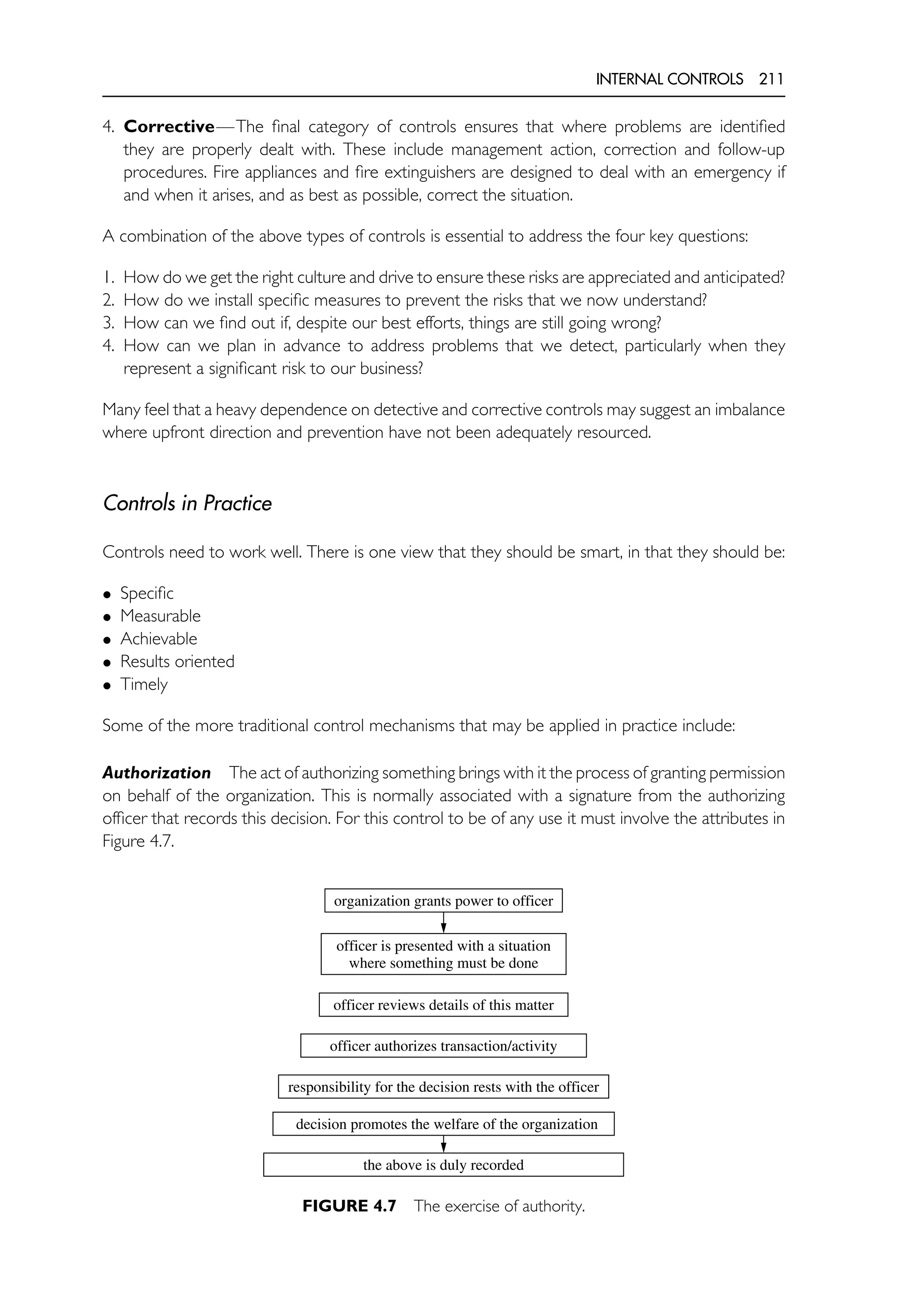

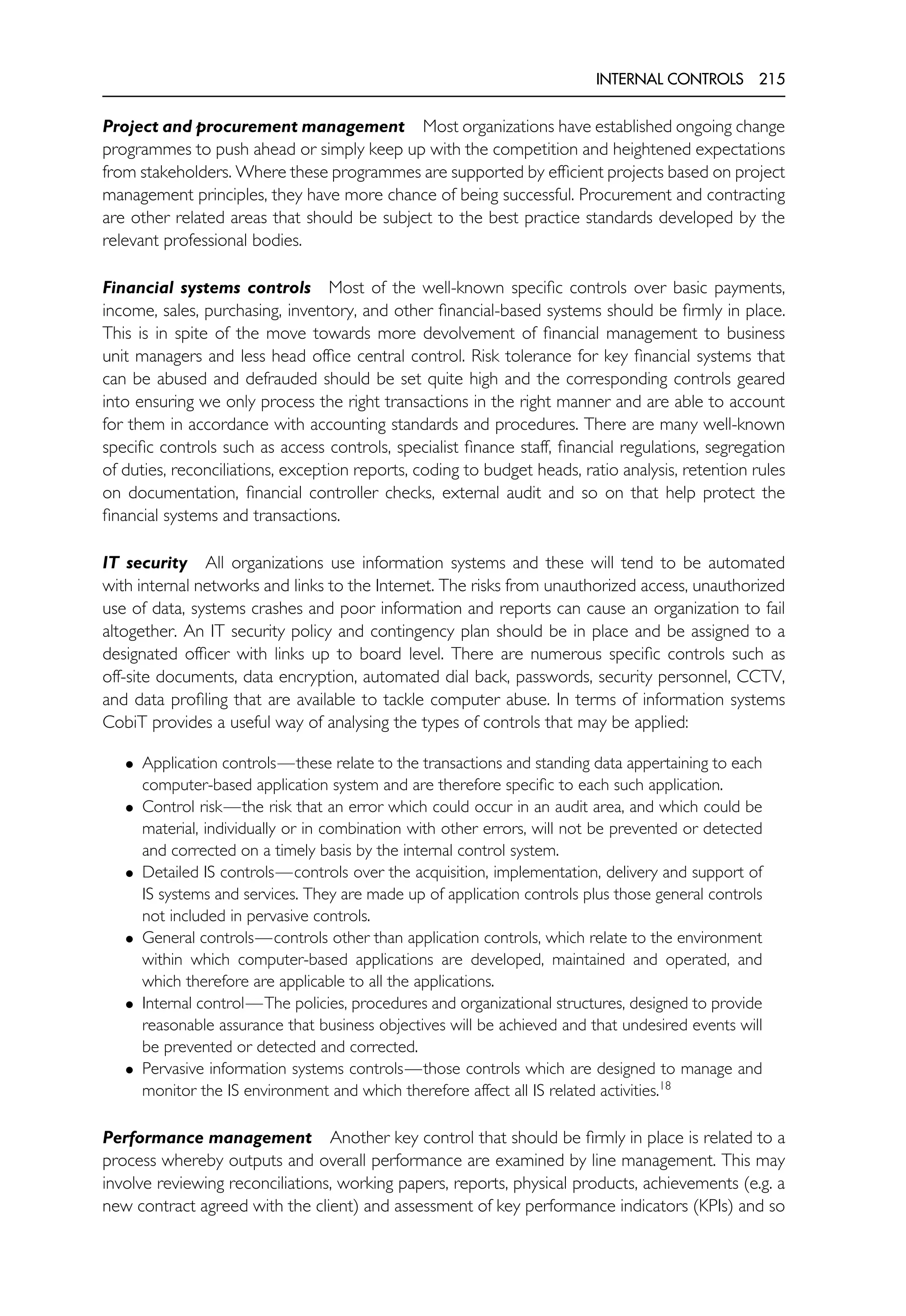

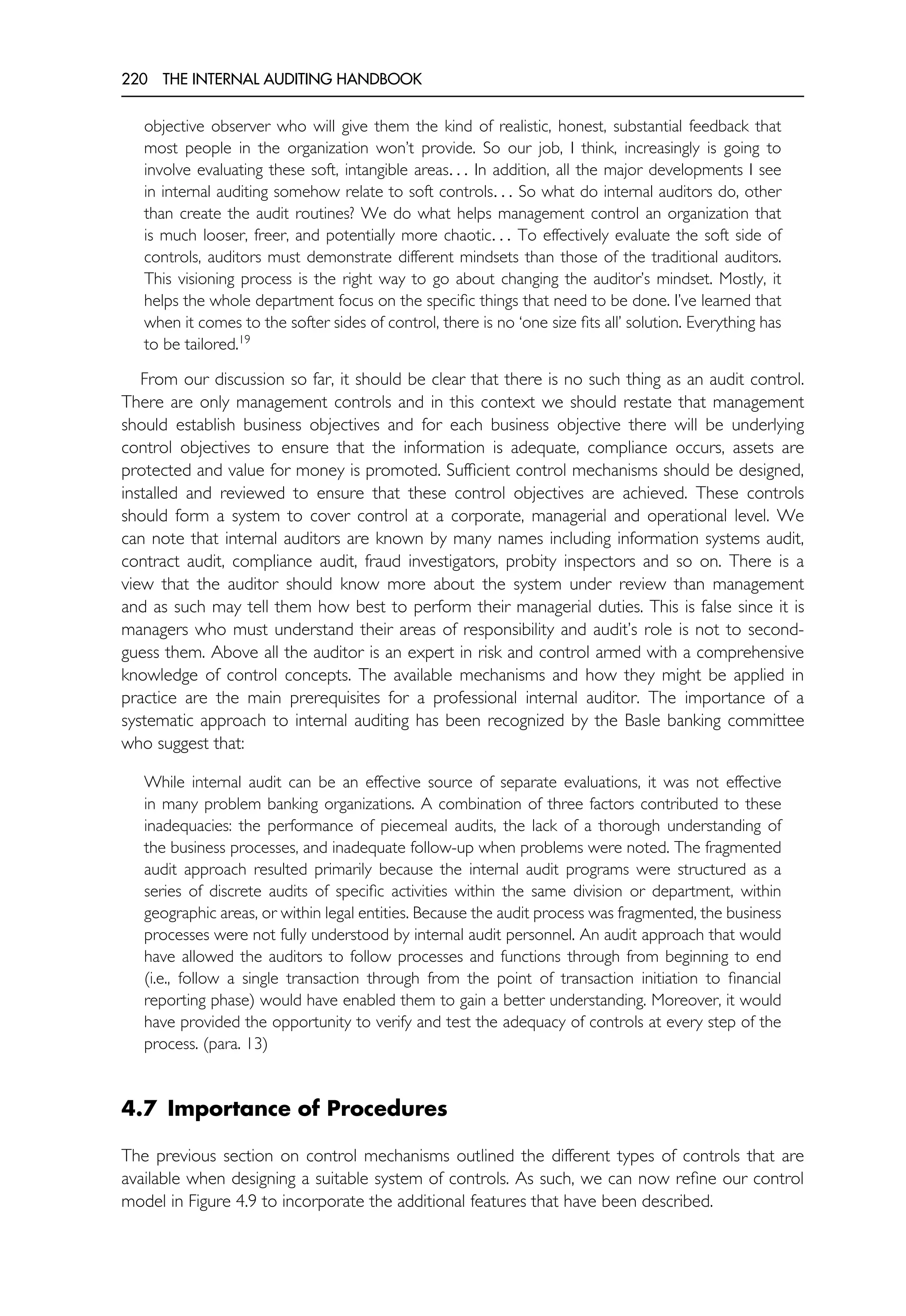

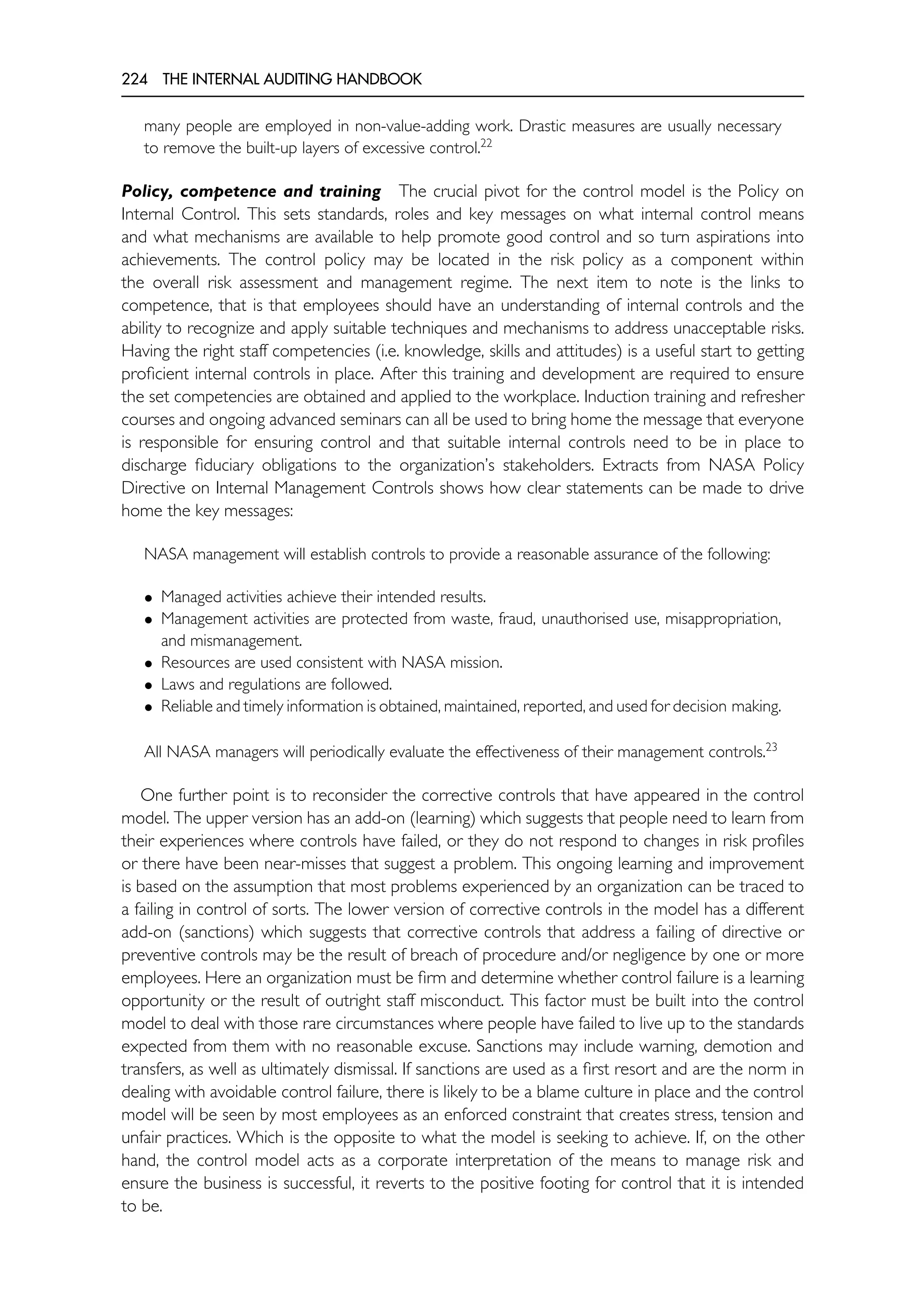

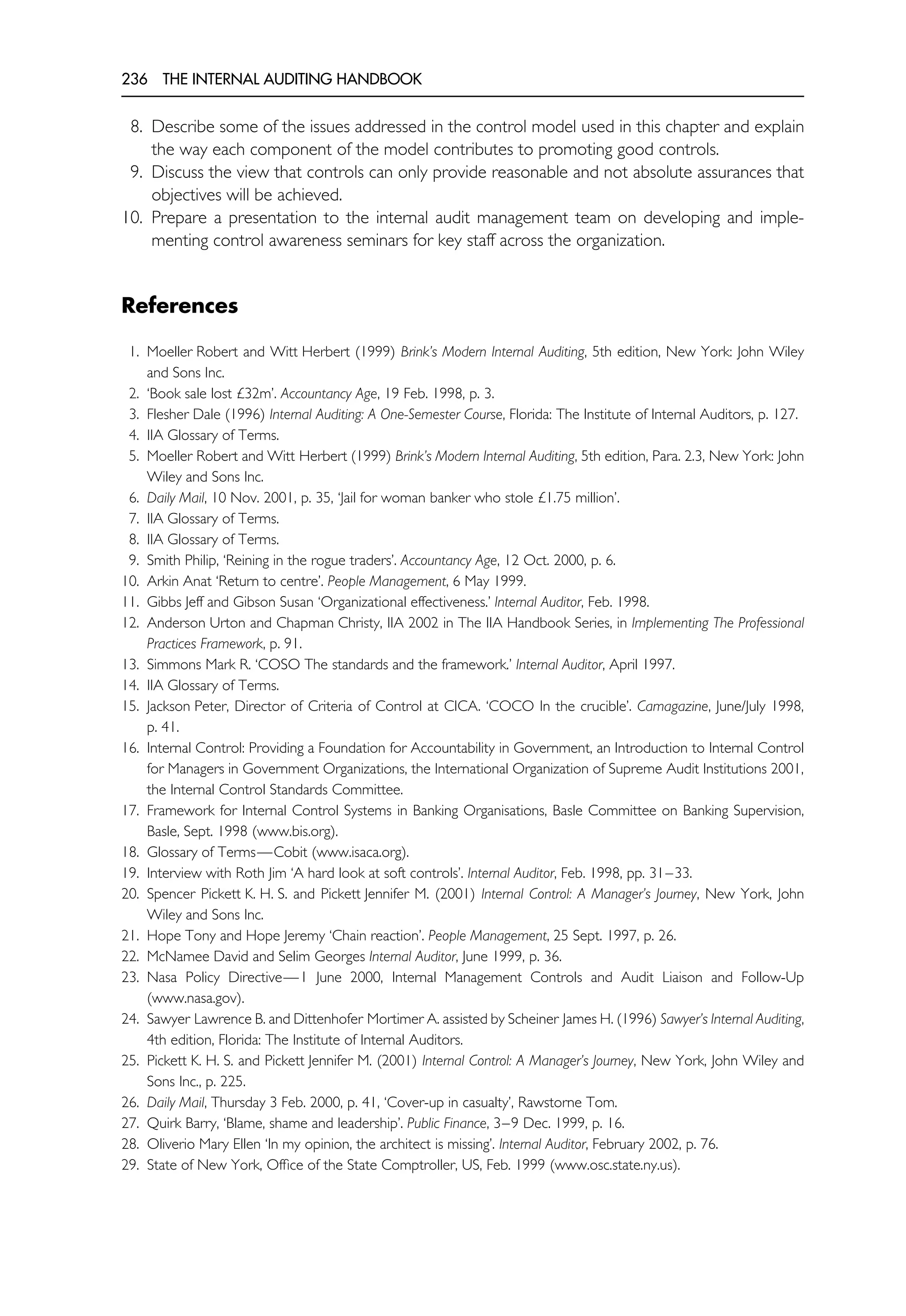

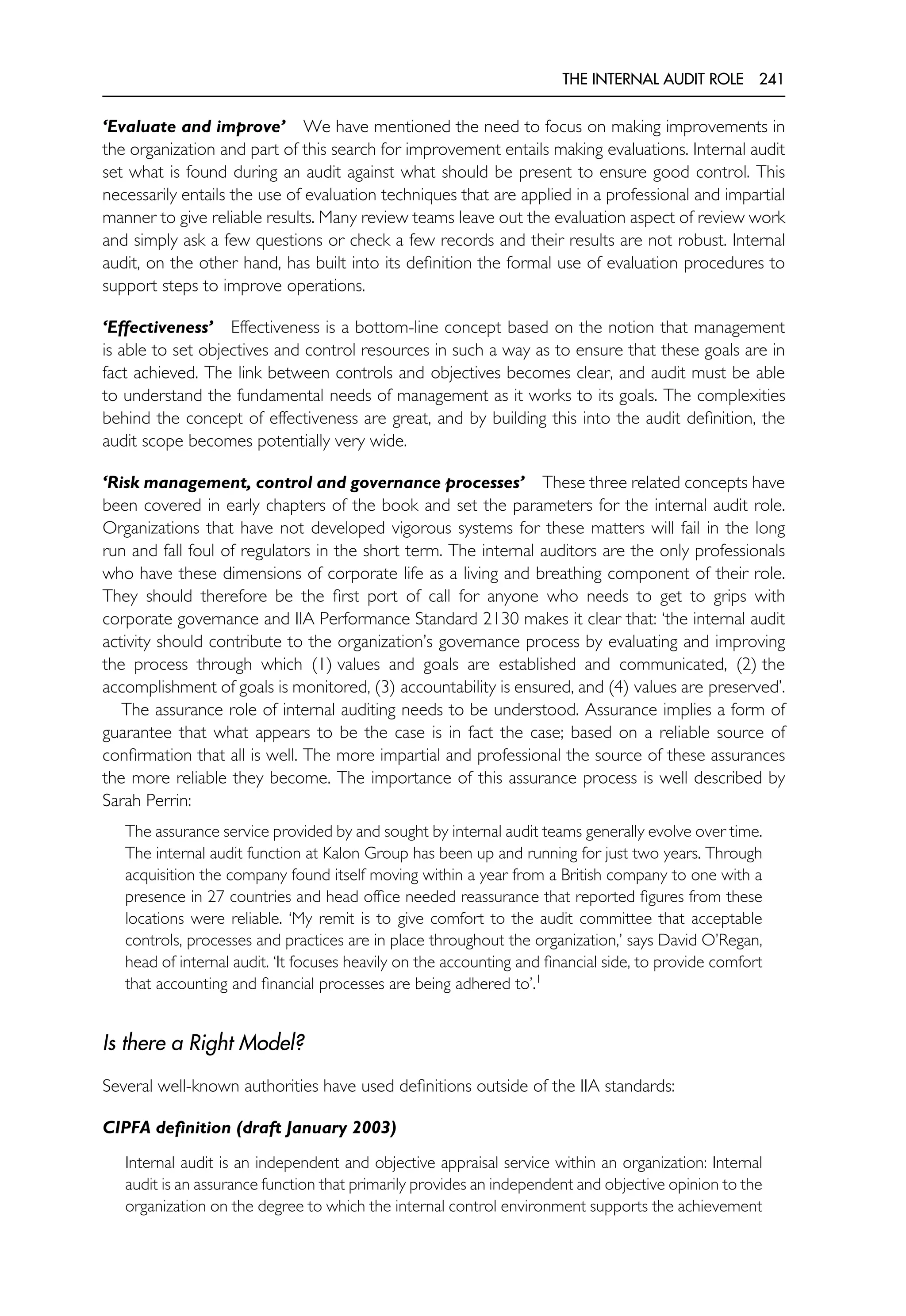

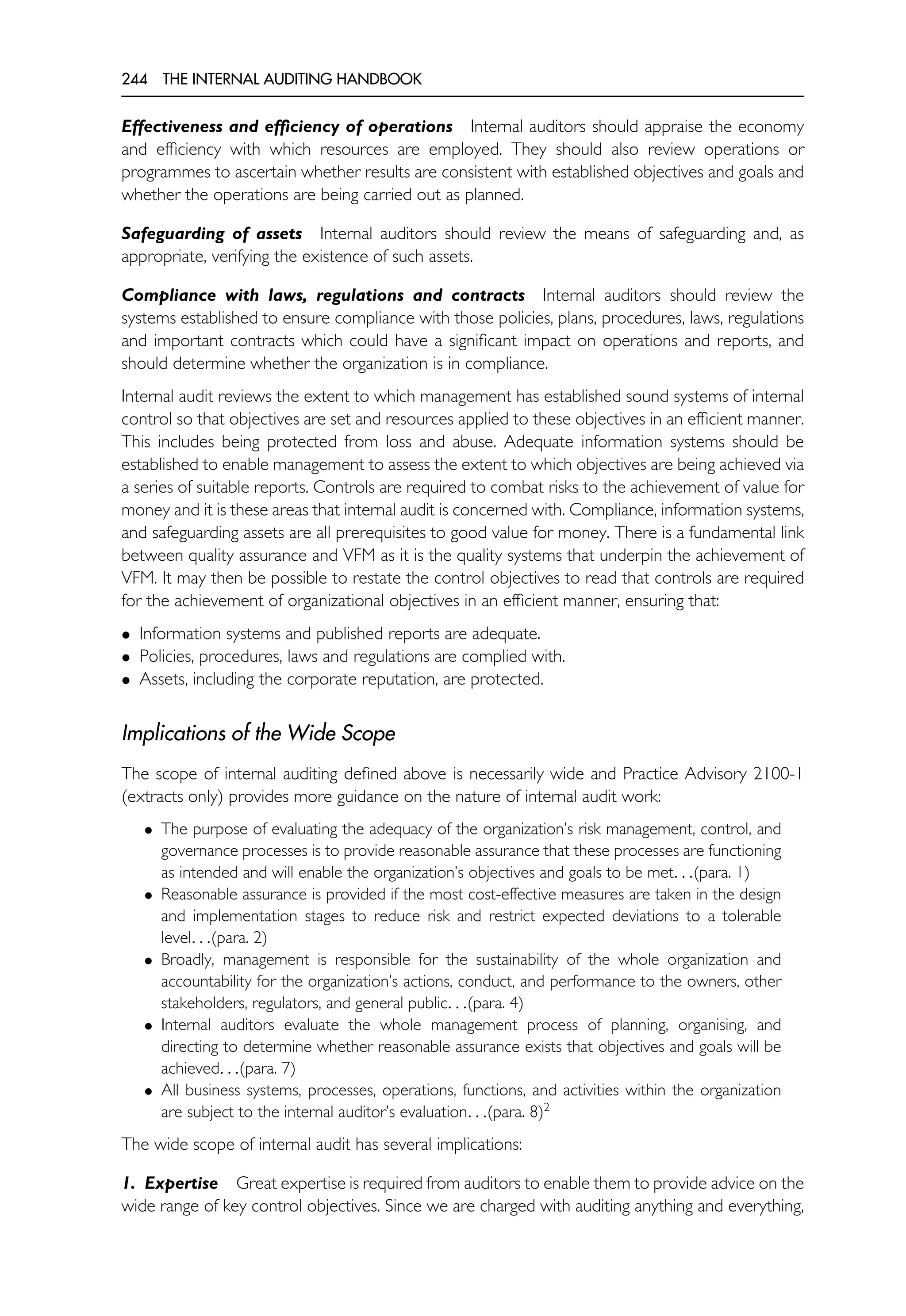

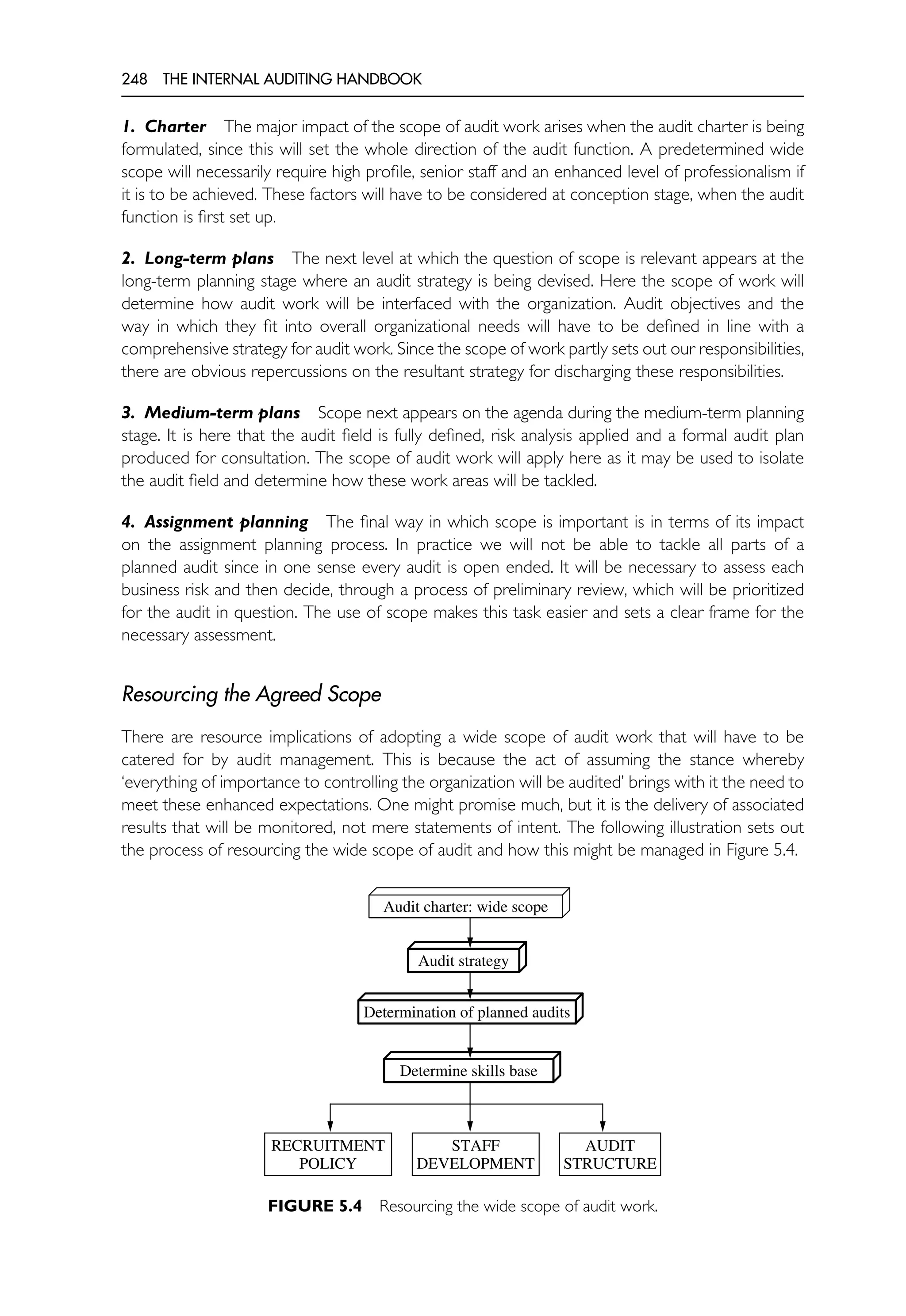

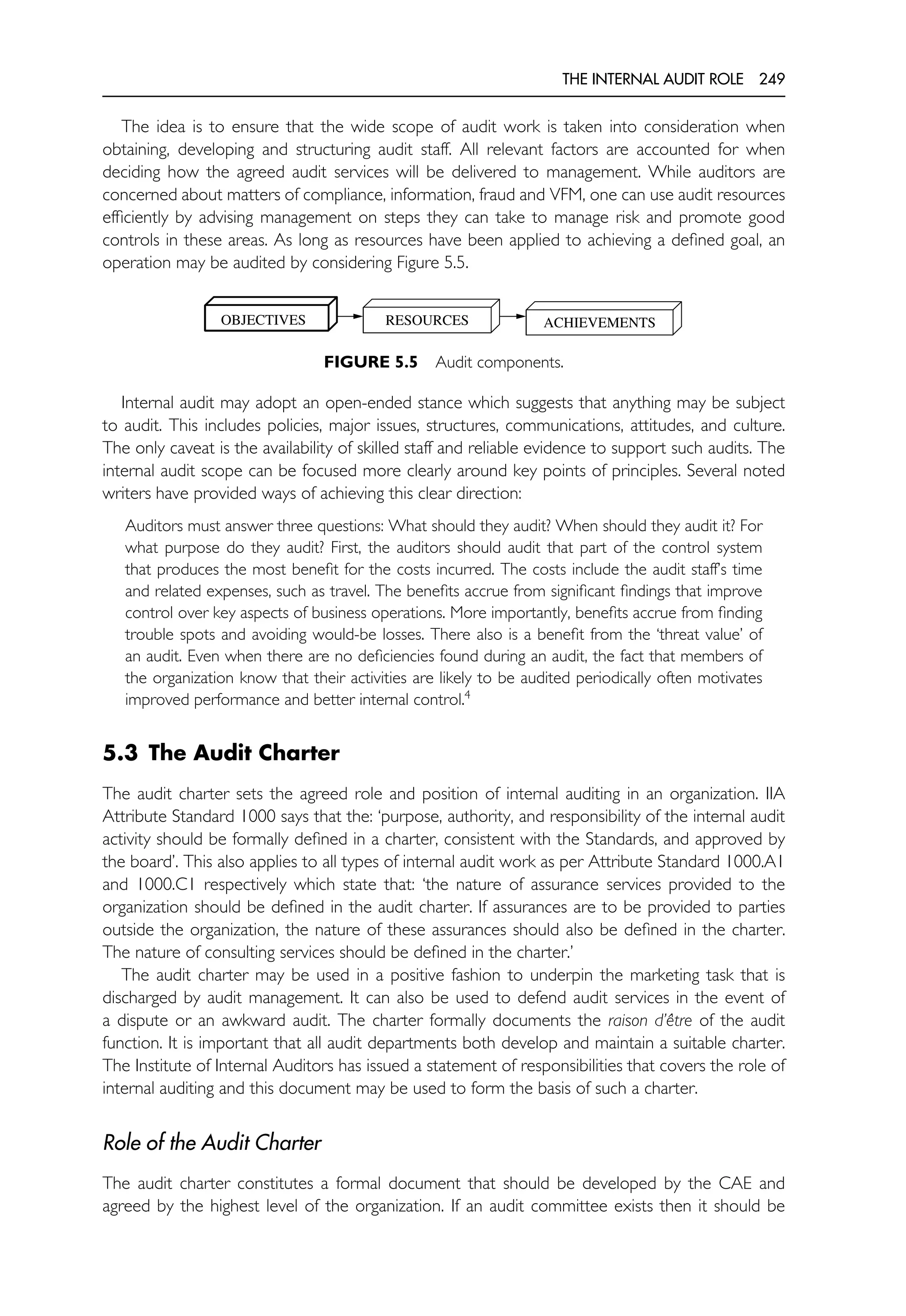

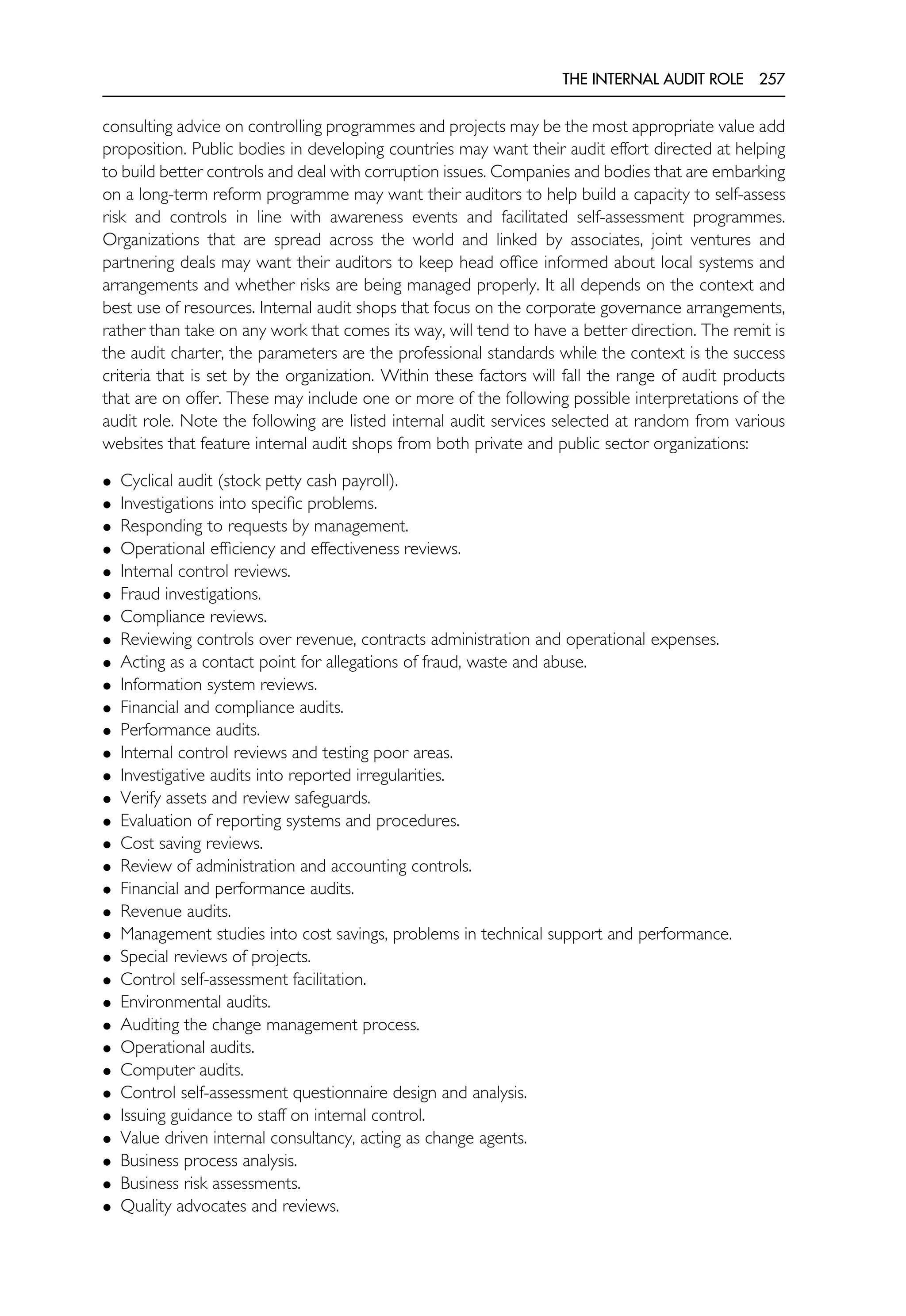

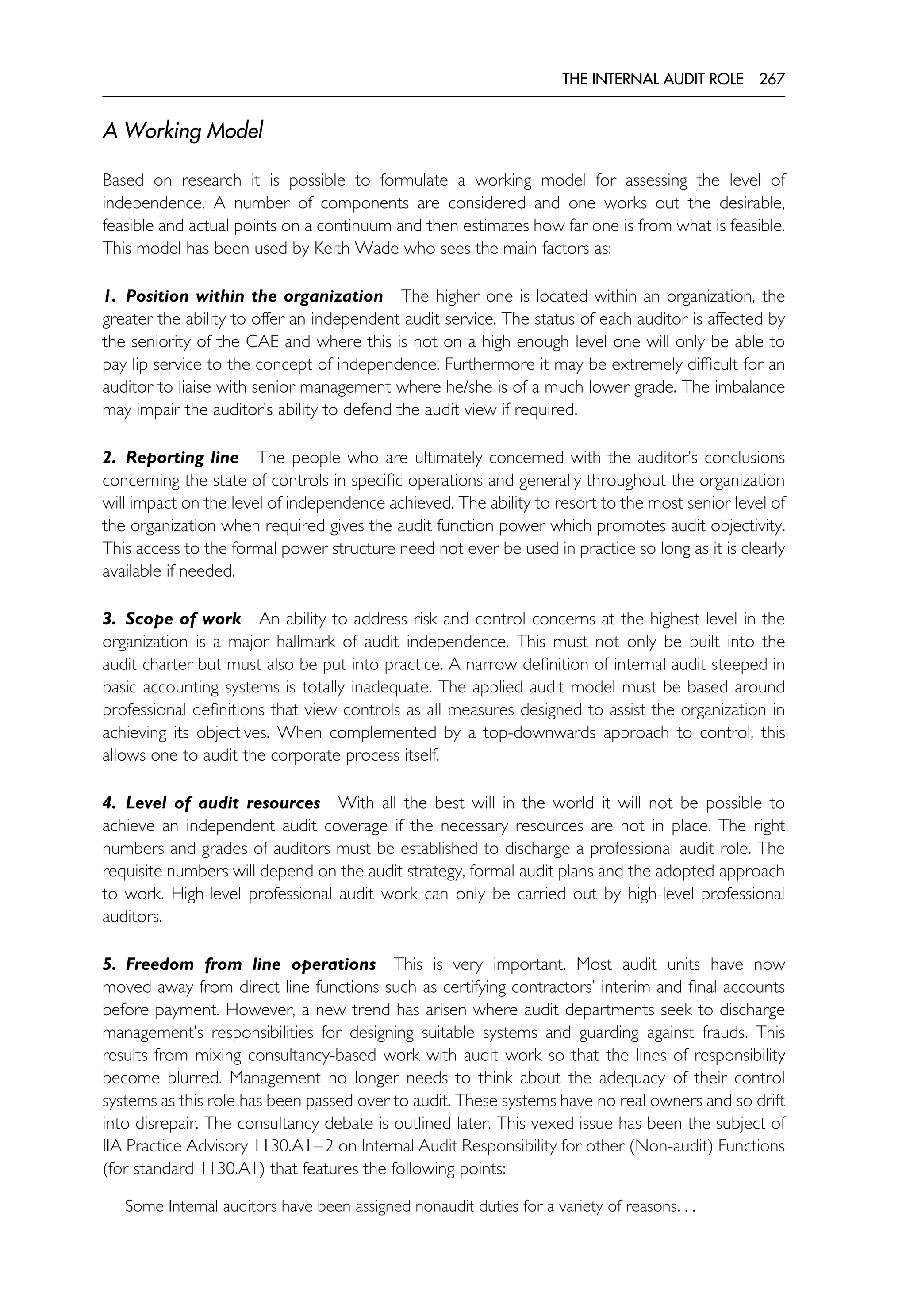

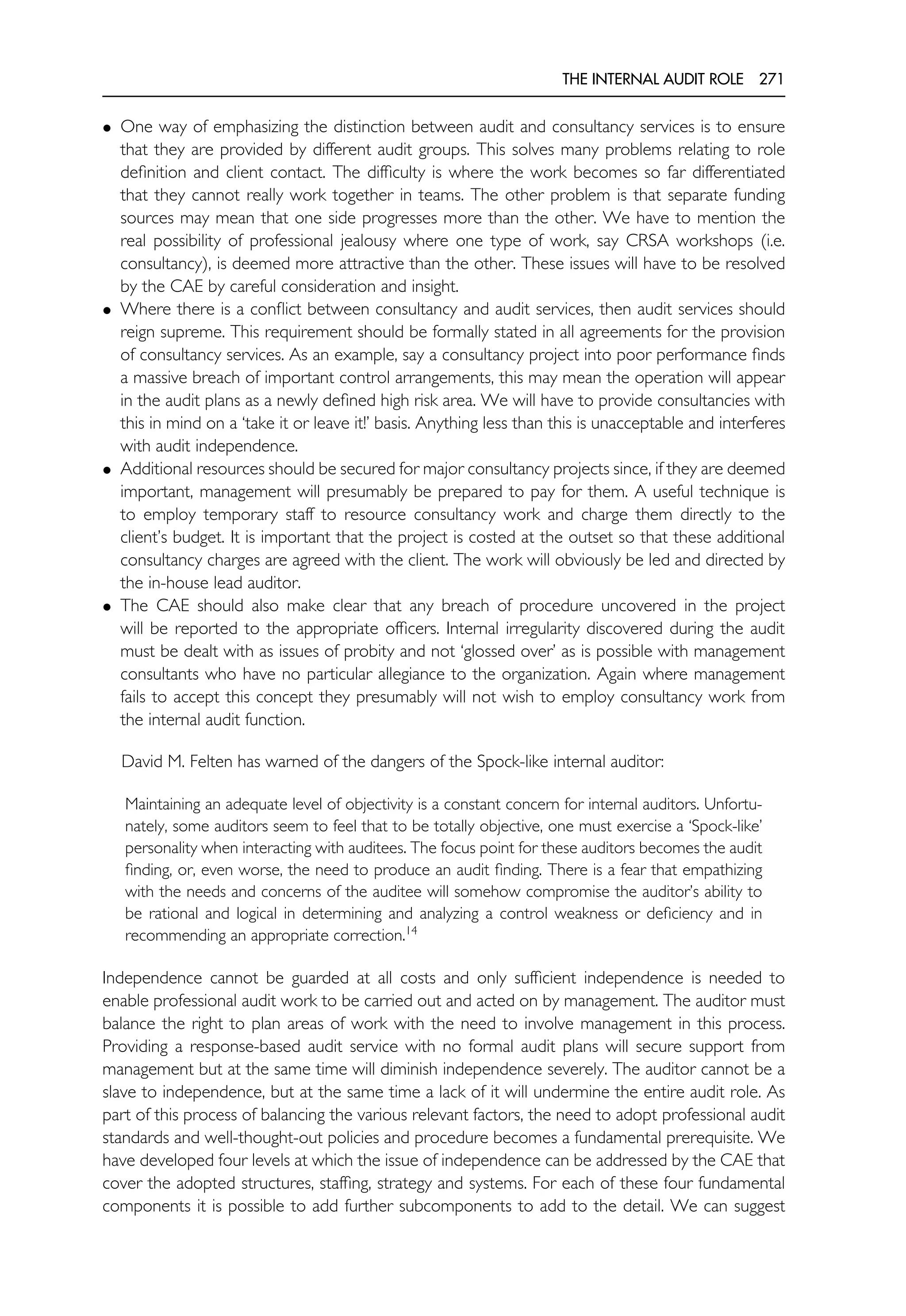

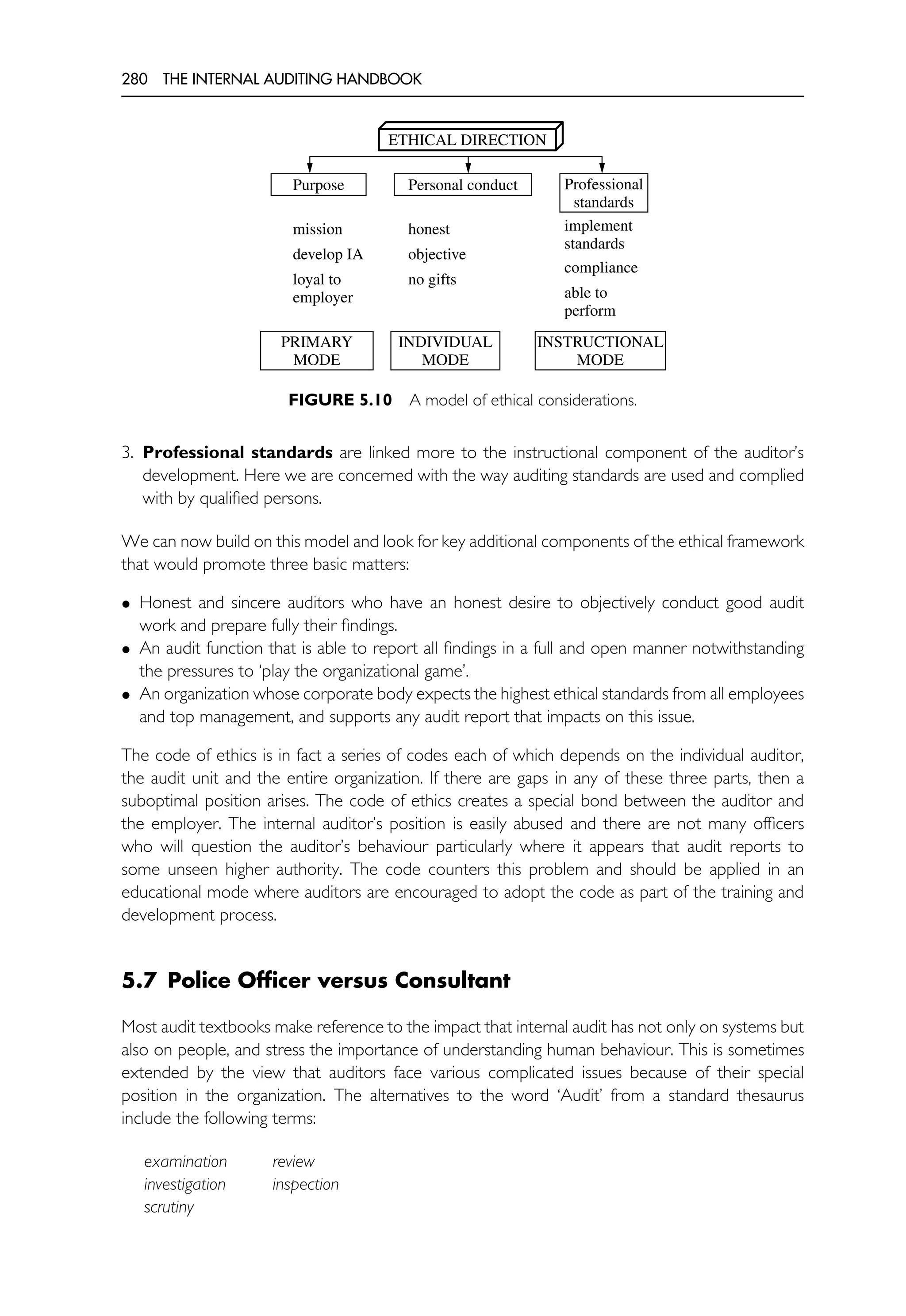

1. Traditional tick and check Many auditors are seen as checkers who spend their time

ticking thousands of documents and records. In this way management may treat the auditor as

someone who has an extremely limited role that requires little skill and professionalism. At the

extreme, managers may view audit staff with disdain and greet their presence with what can only

be termed ridicule. This position can account for the strained atmosphere that many an auditor

has faced when meeting with client managers at the outset of an audit. The perception that

operational management is very busy doing important work while the auditor is simply checking

some of the basic accounting data that relates to the area can create a great imbalance. This sets

the auditor at a disadvantage from day one of the audit. Where the auditor is only concerned

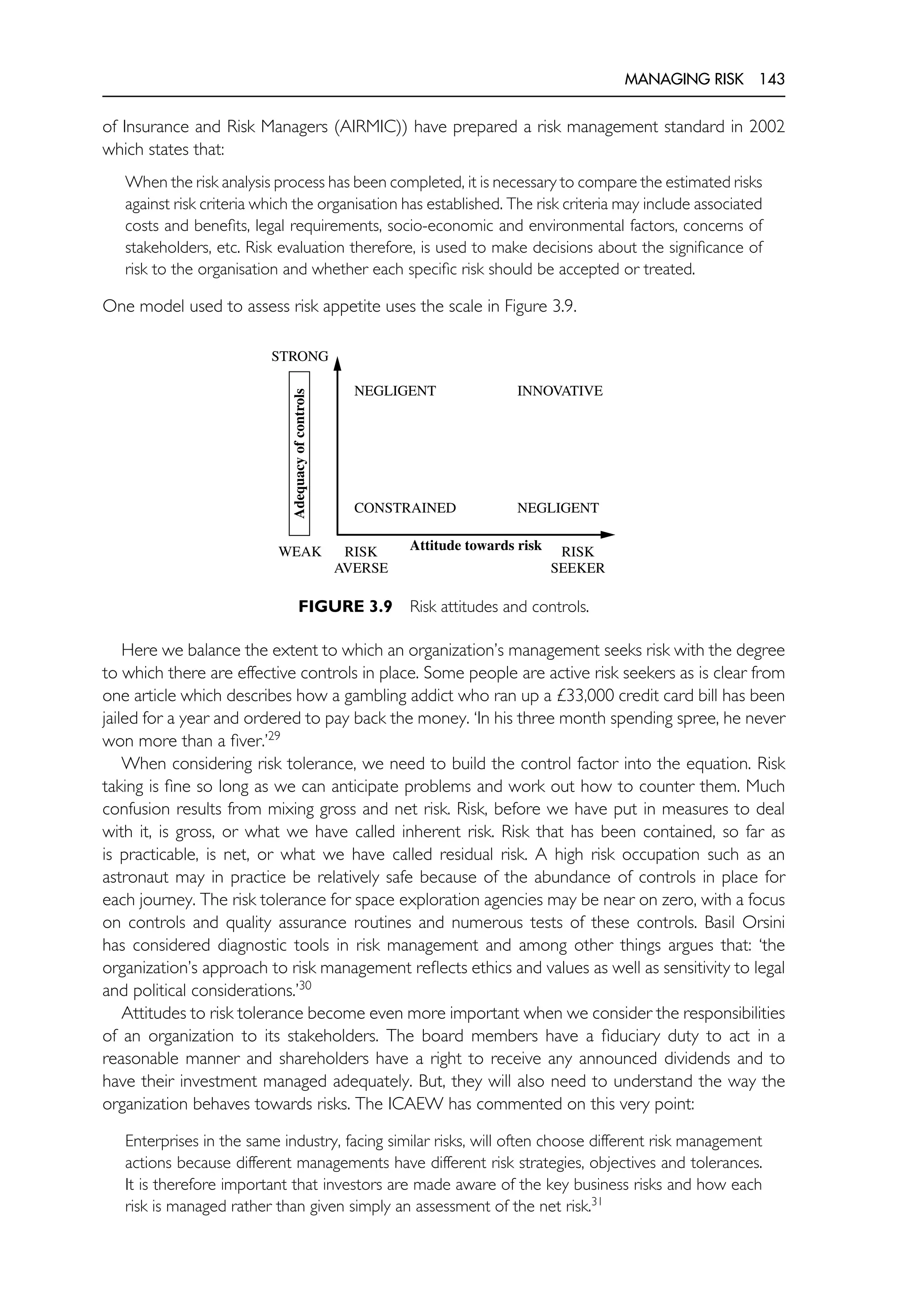

with detailed testing programmes then this view is actually reinforced (see Figure 5.12).

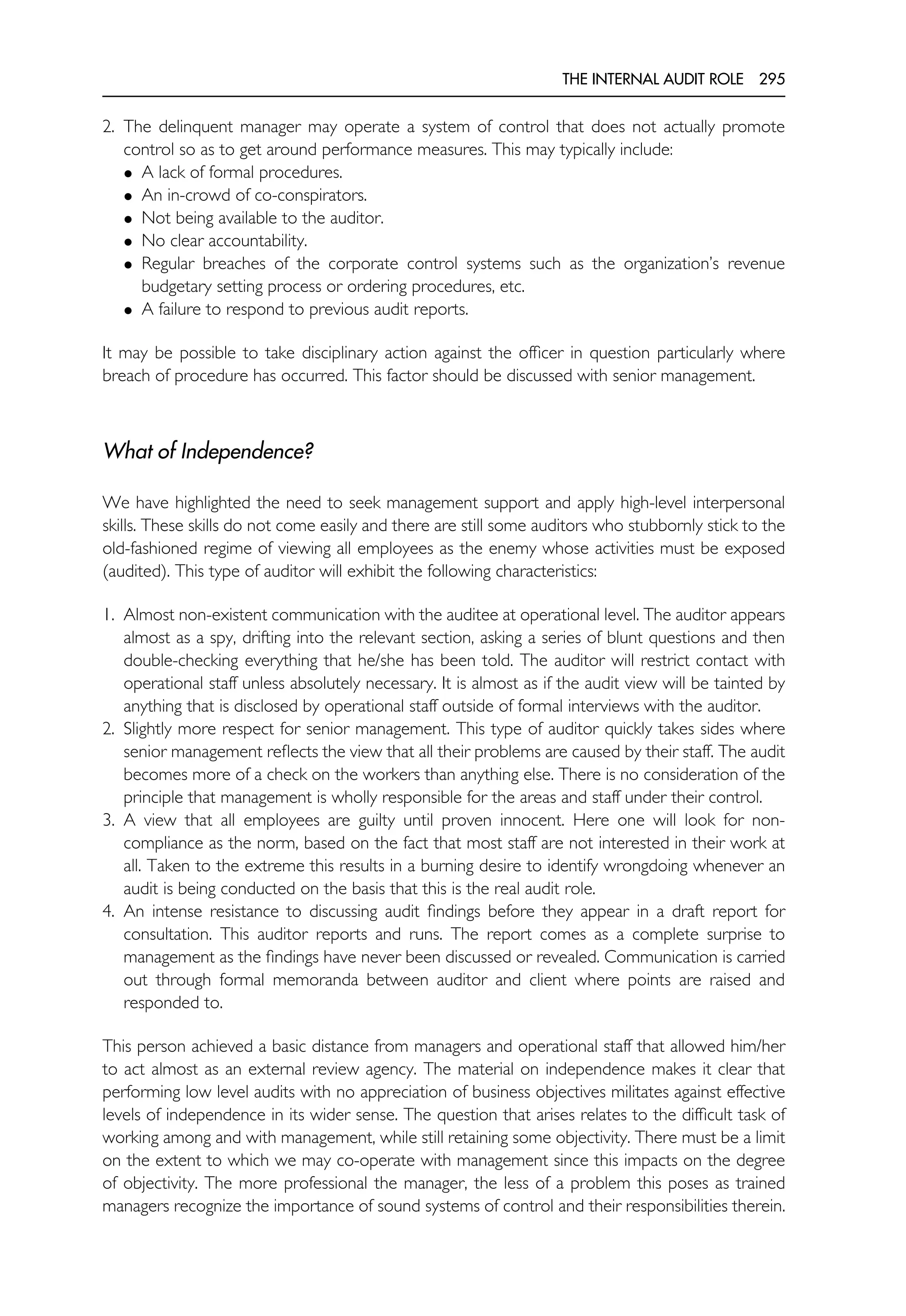

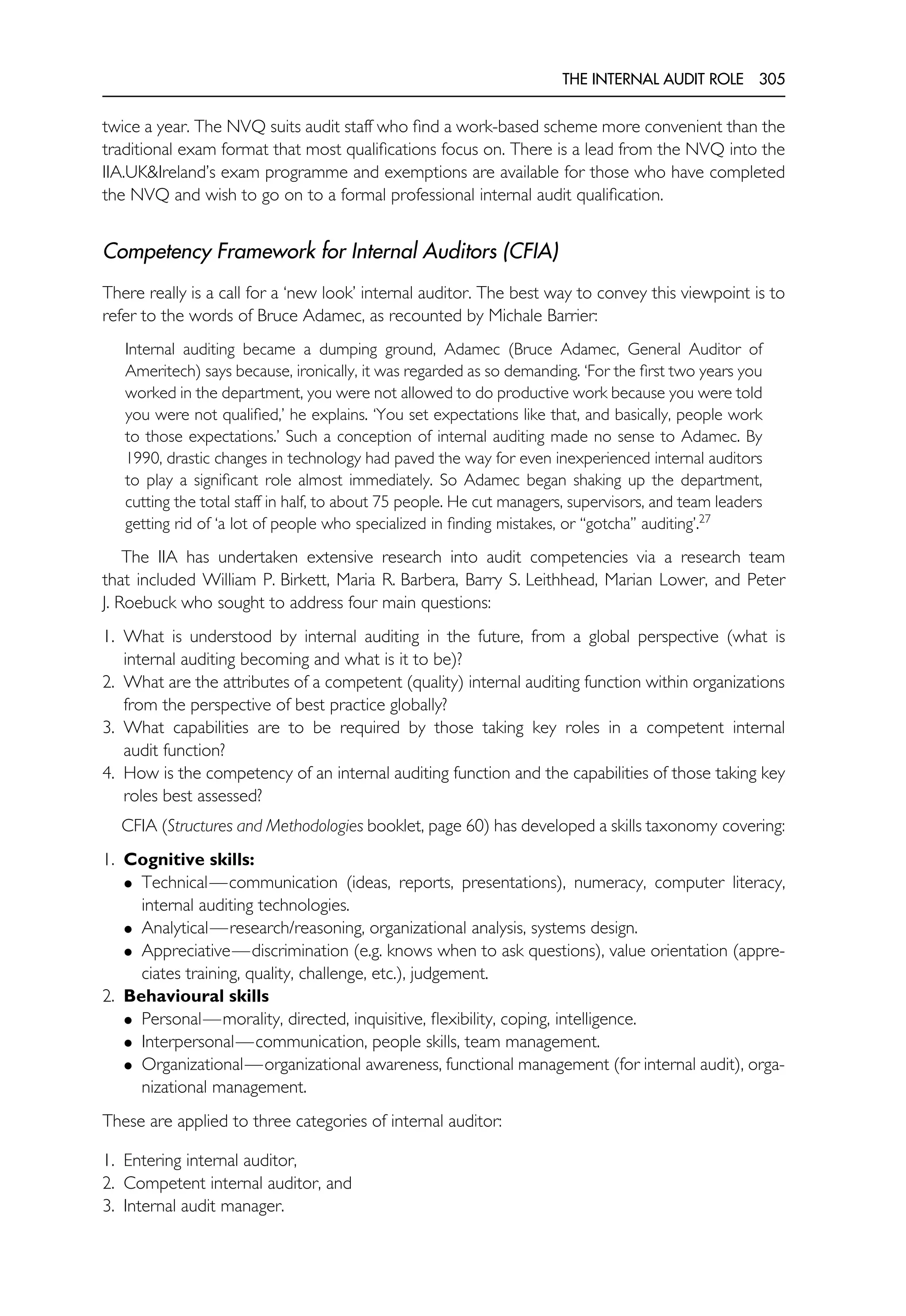

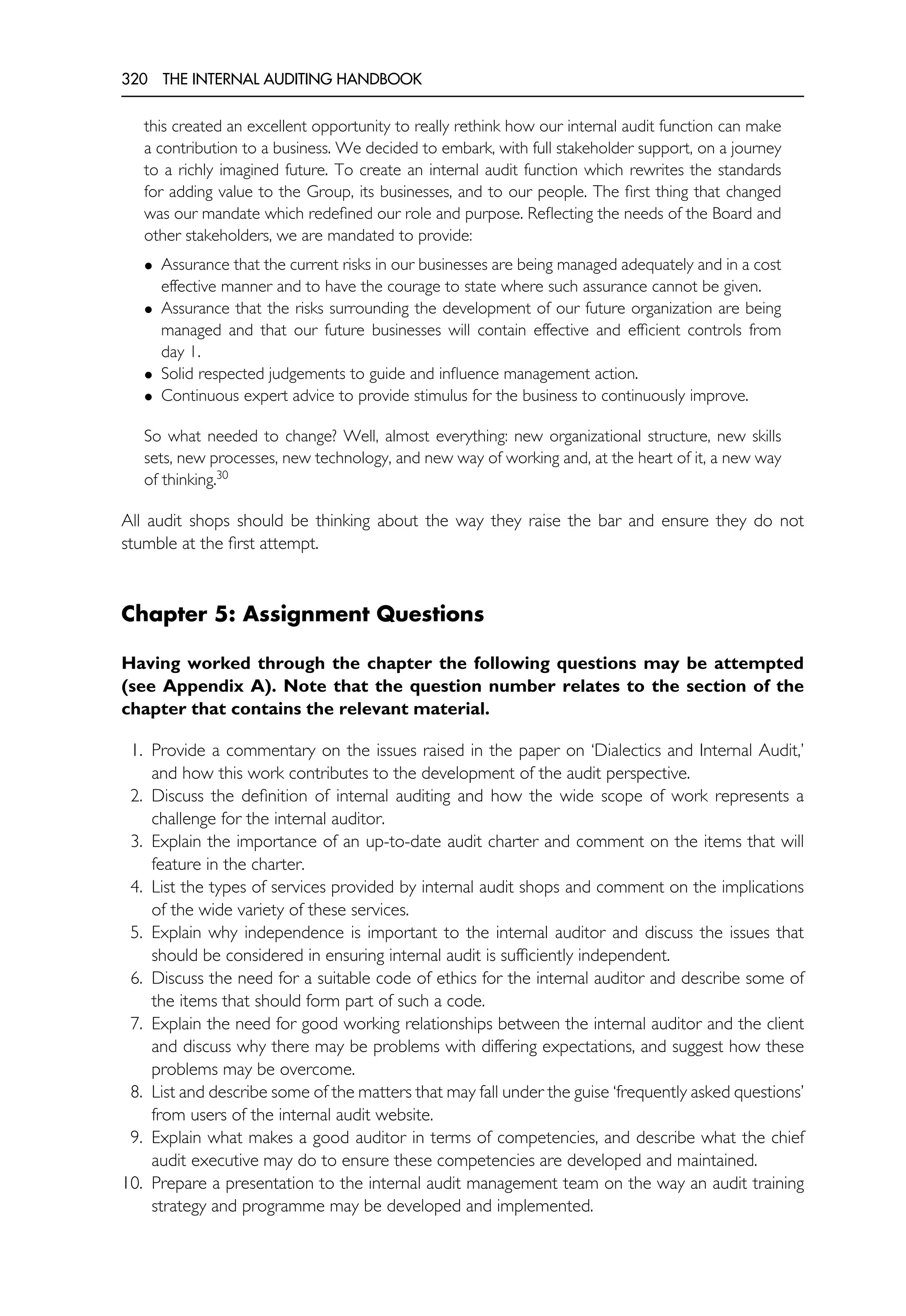

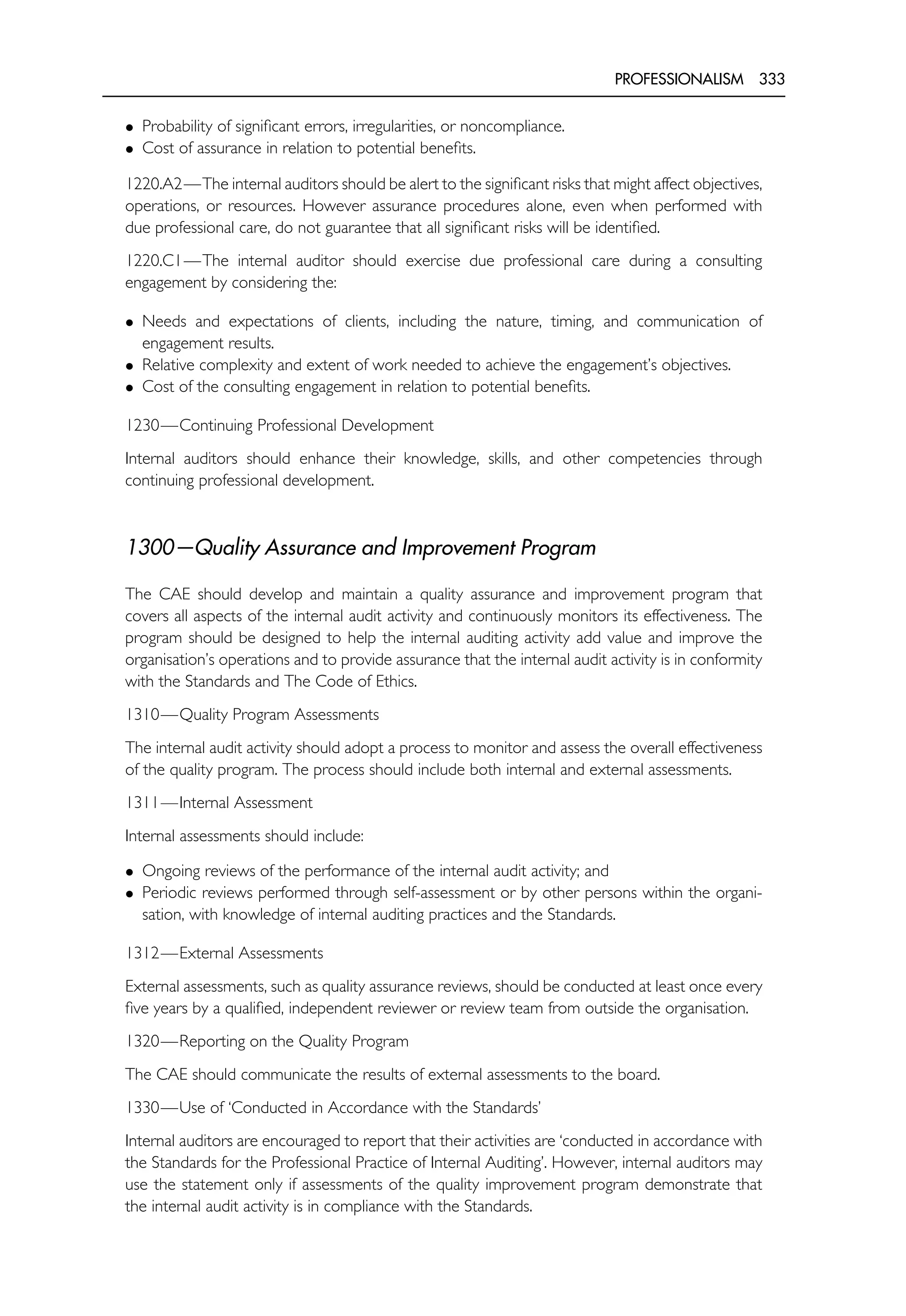

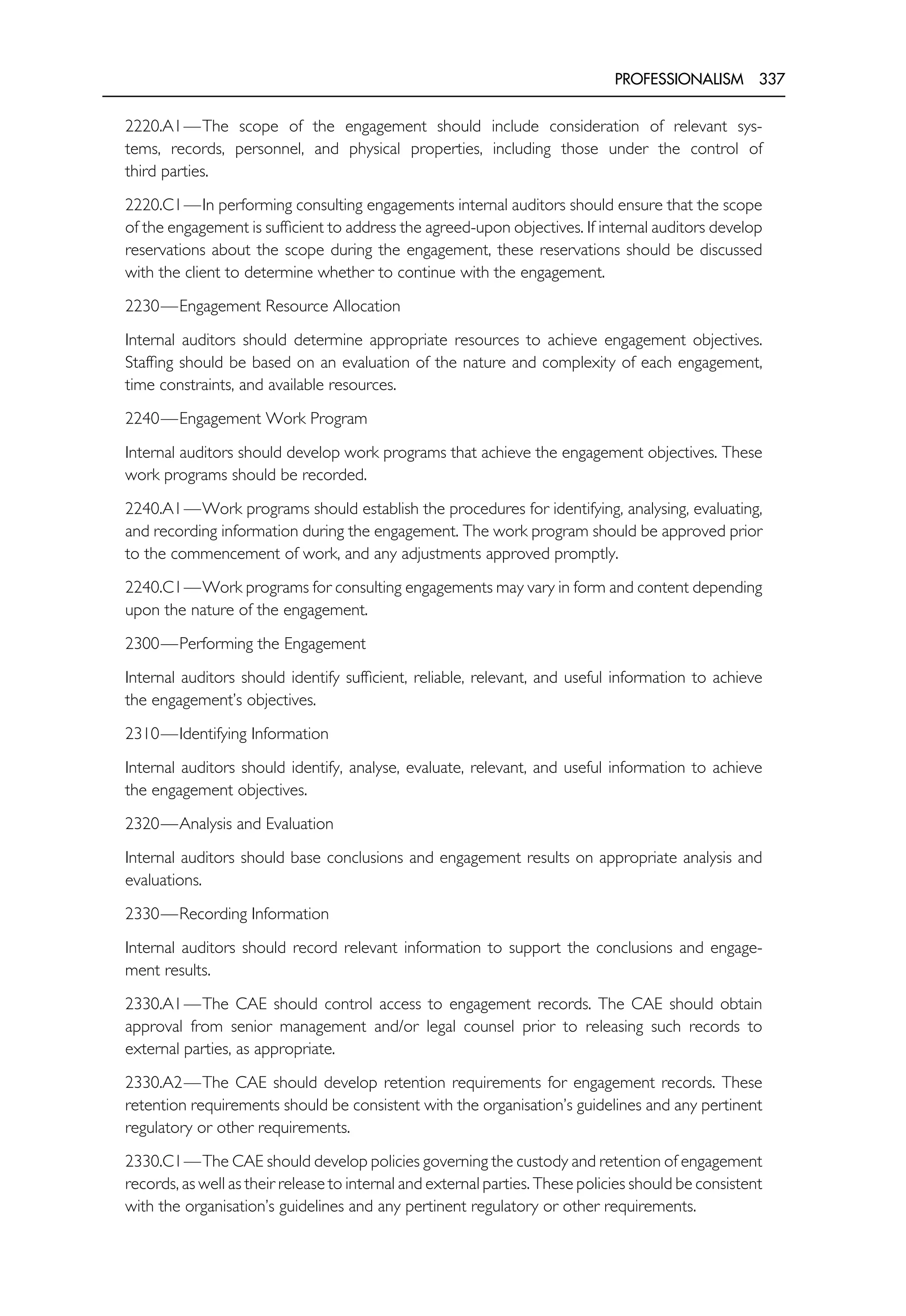

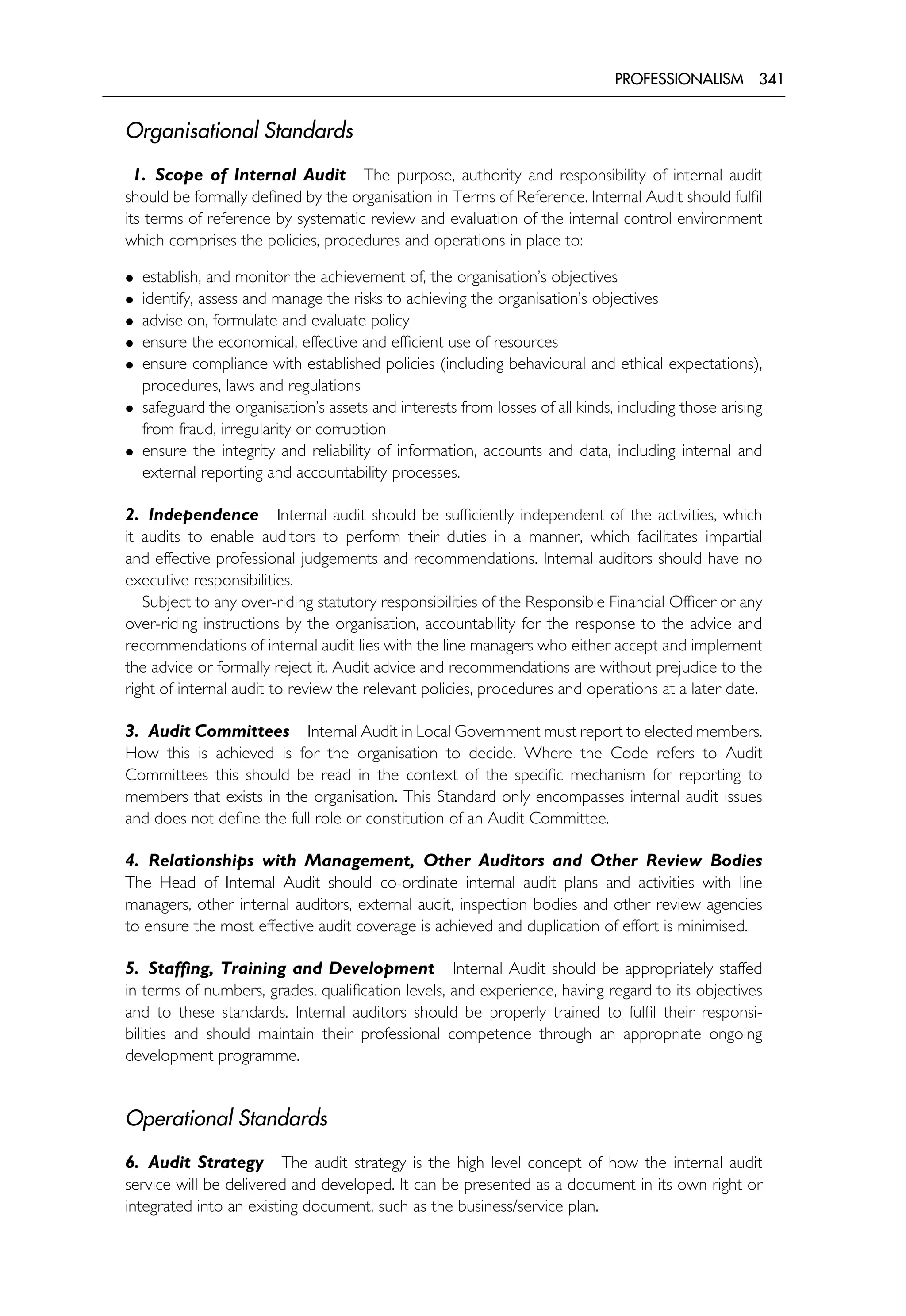

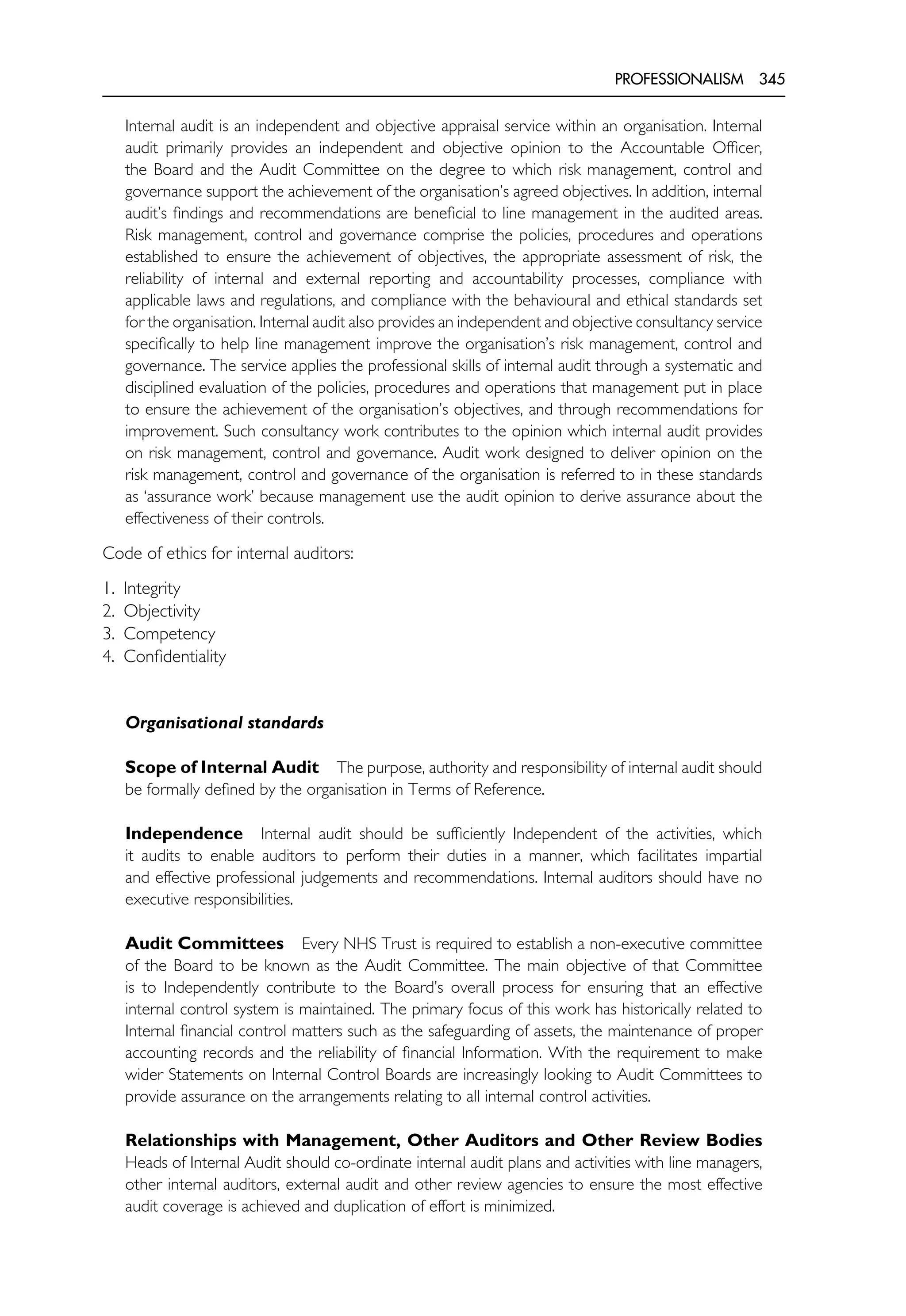

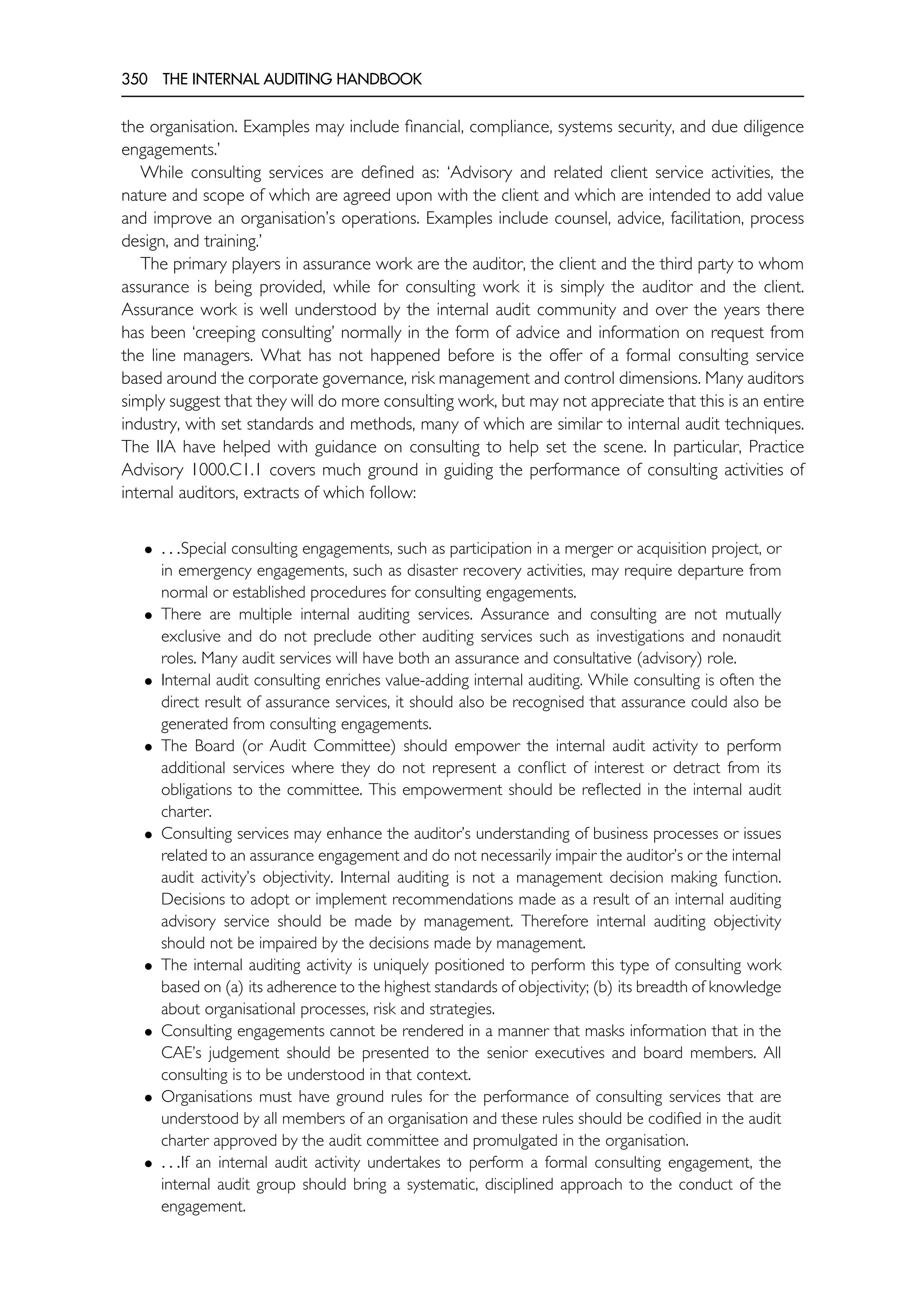

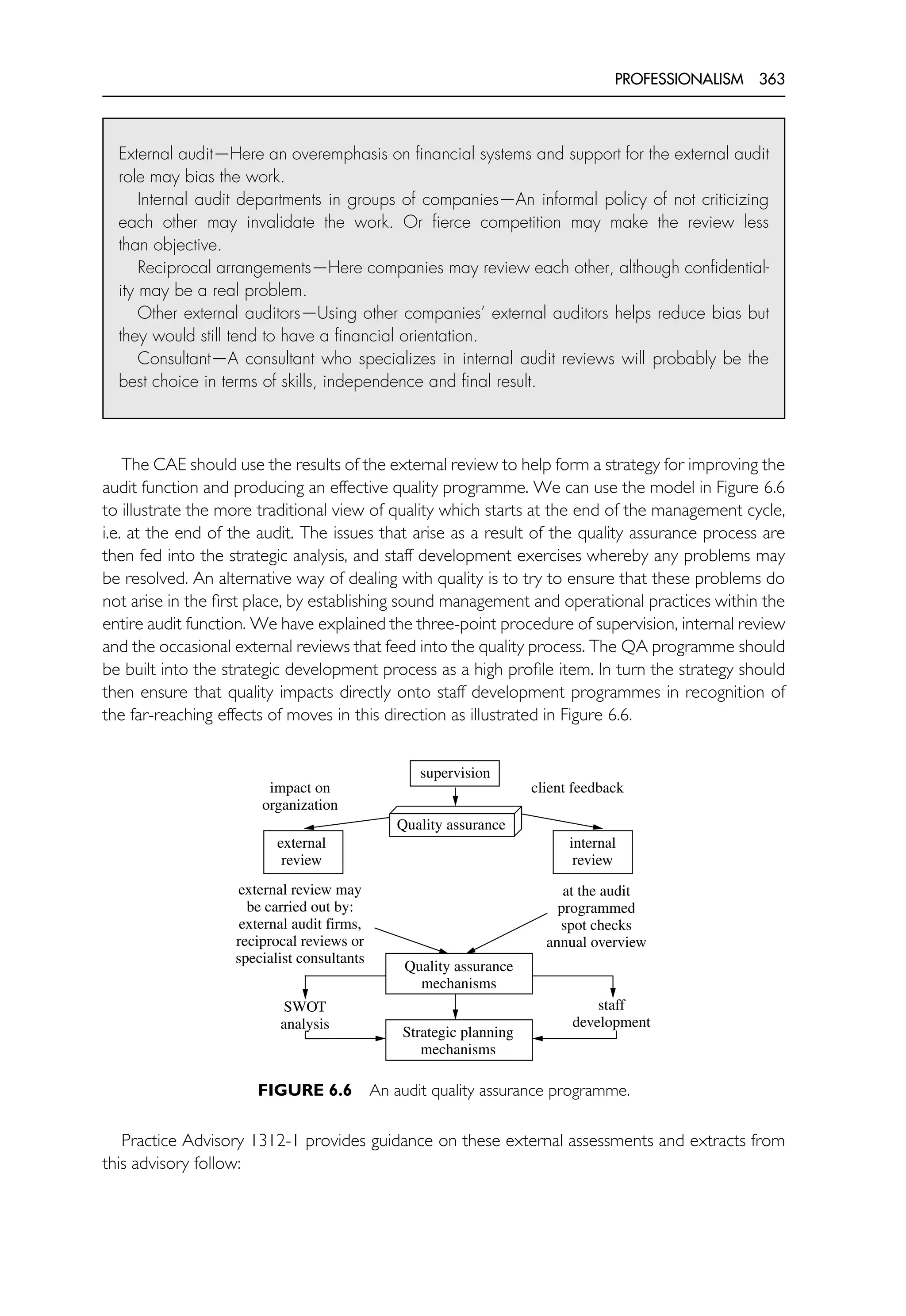

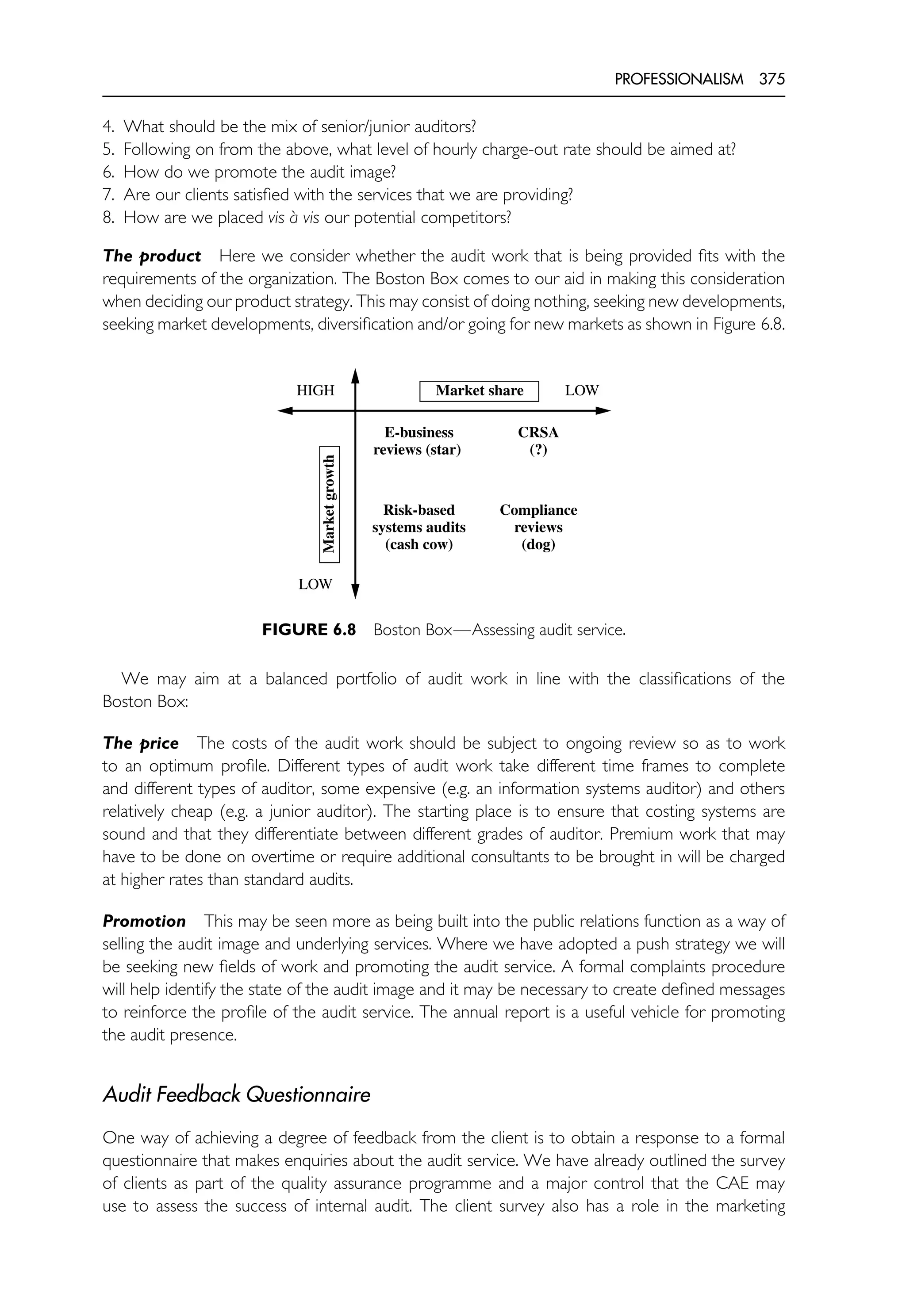

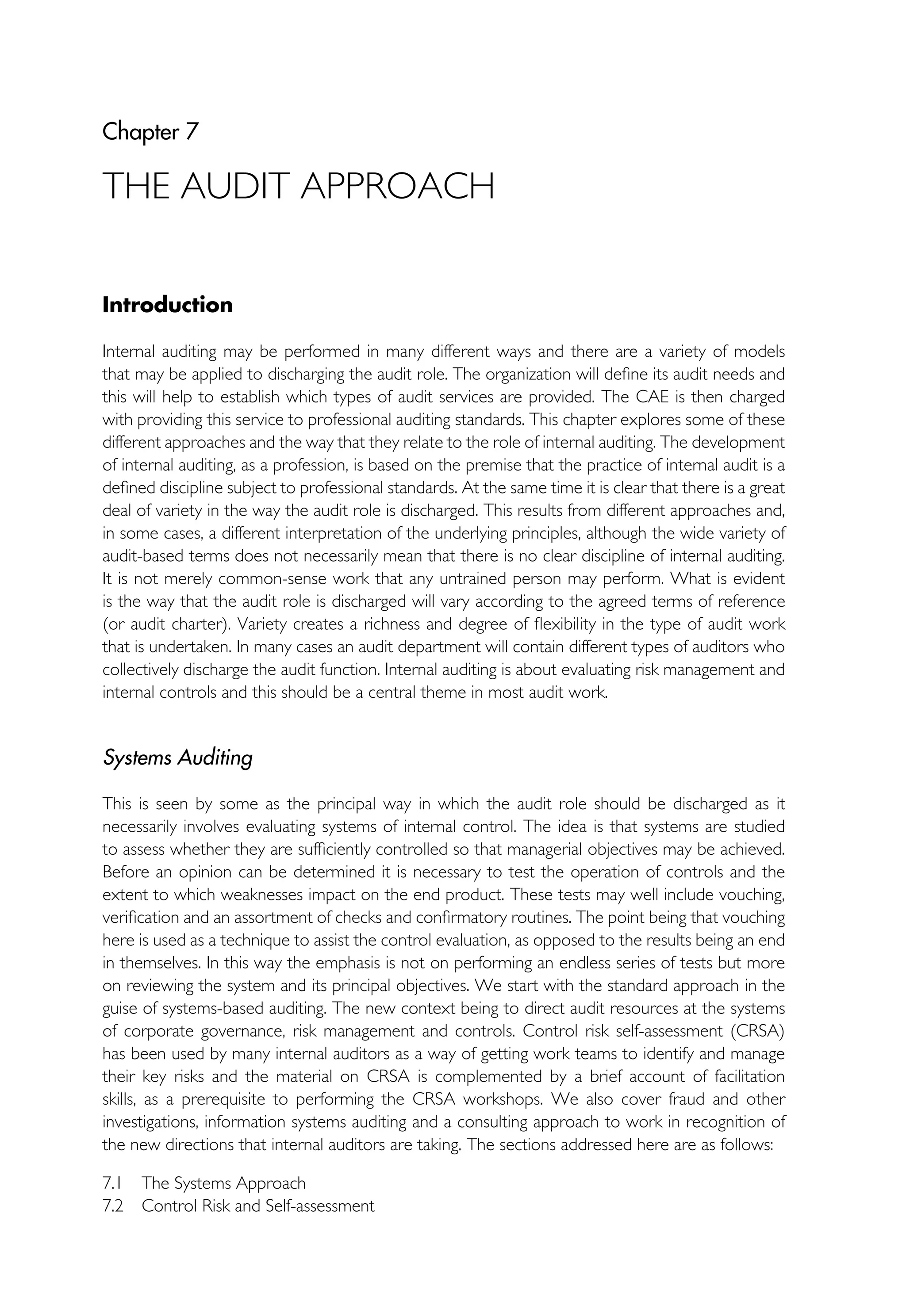

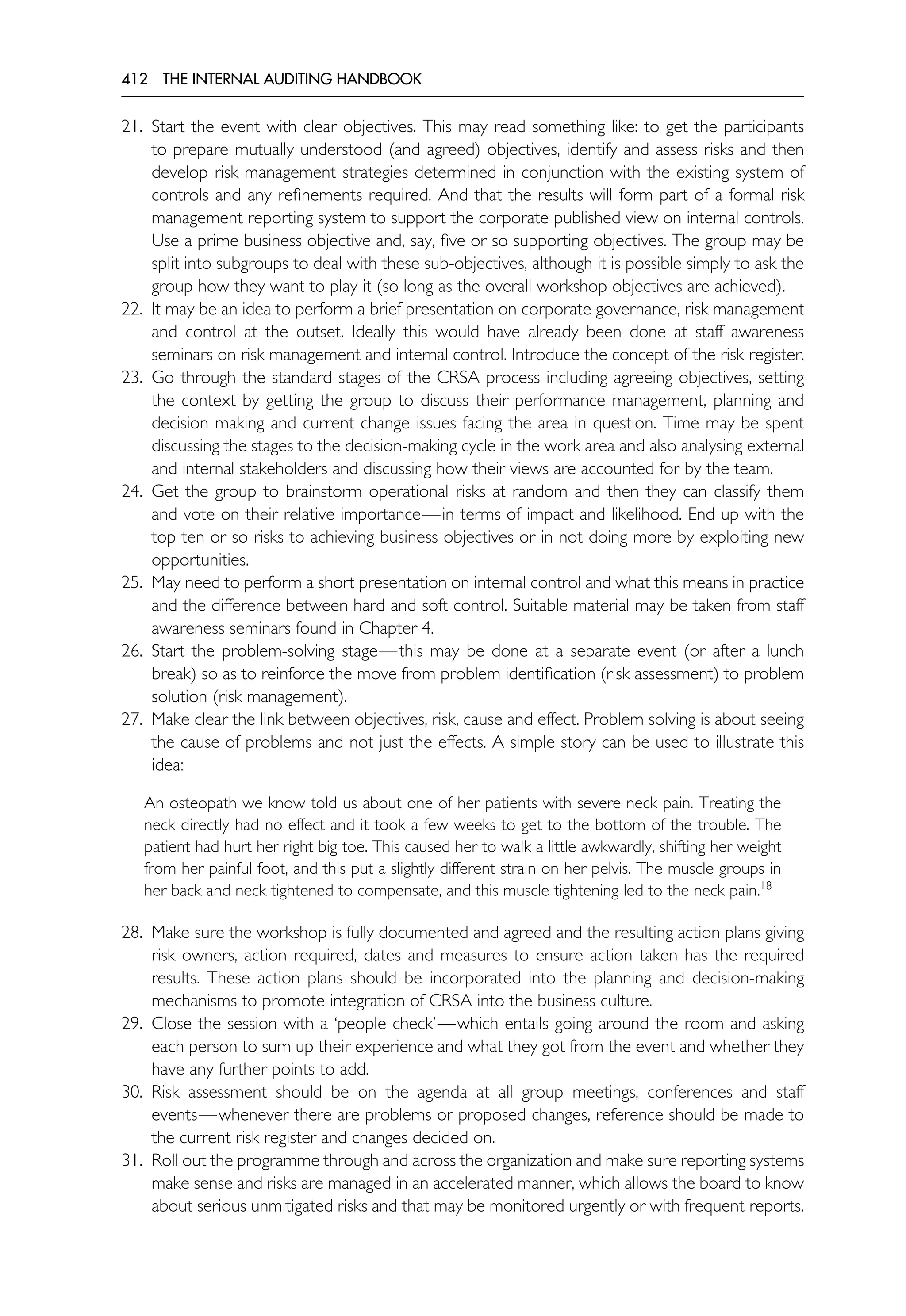

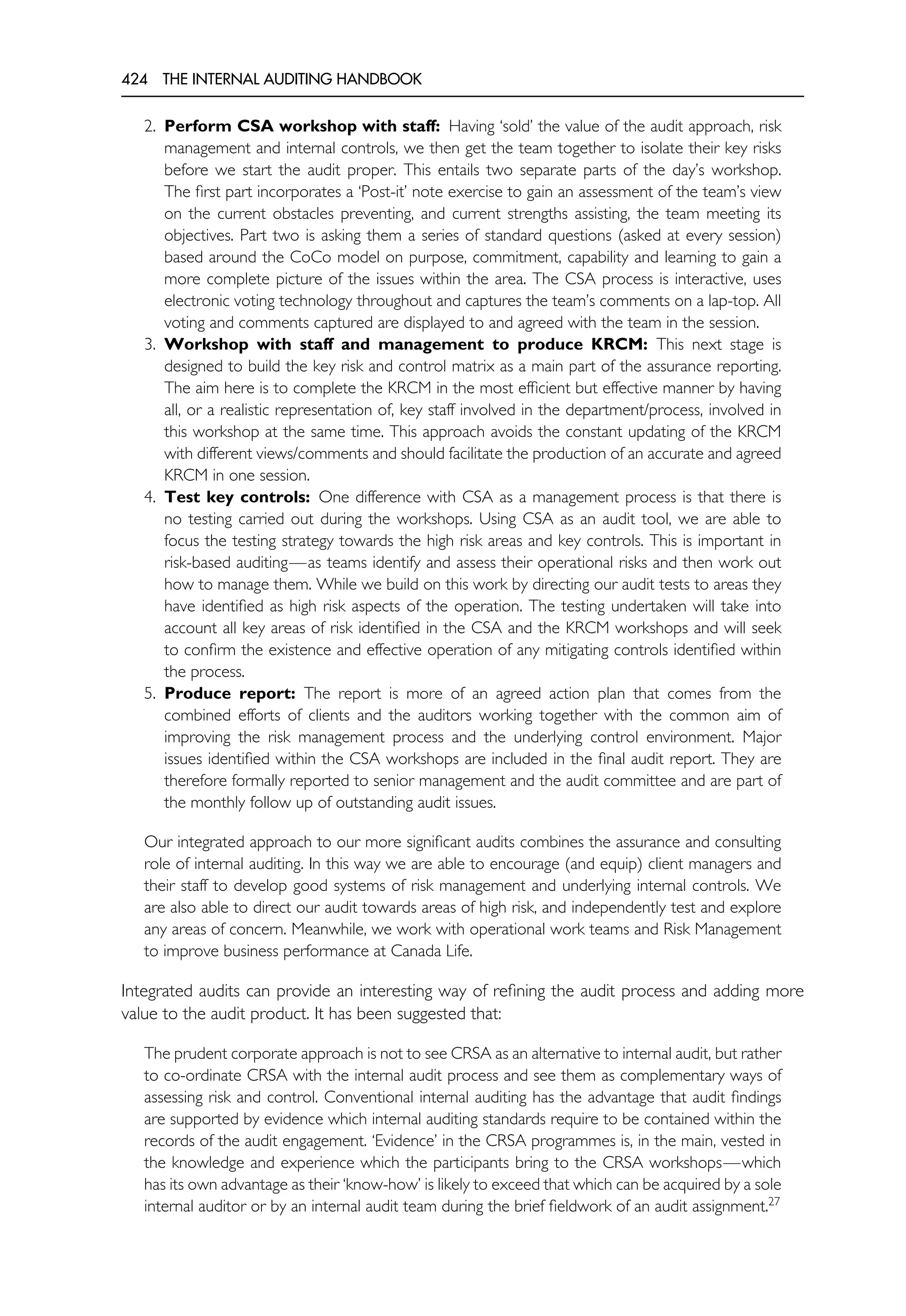

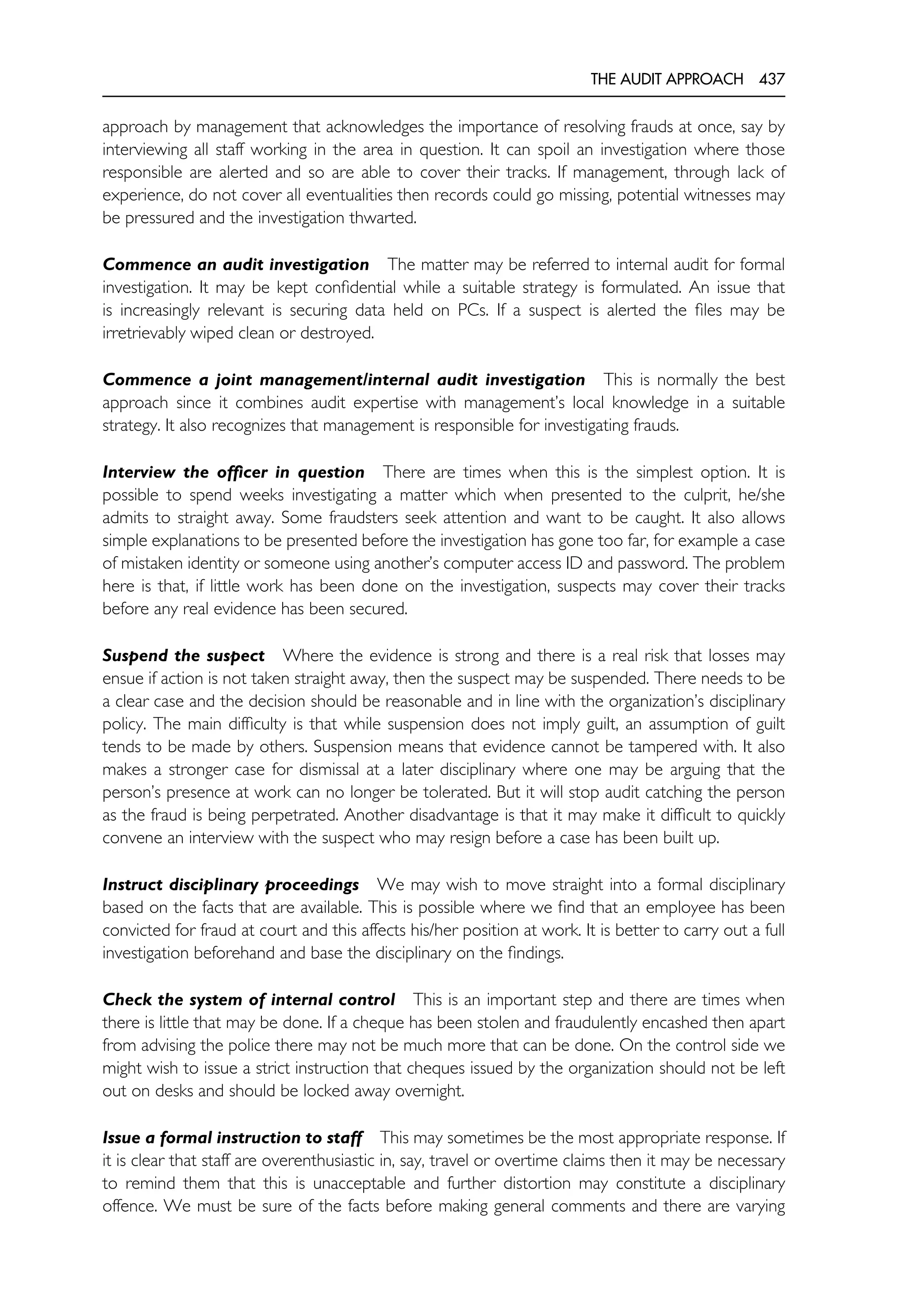

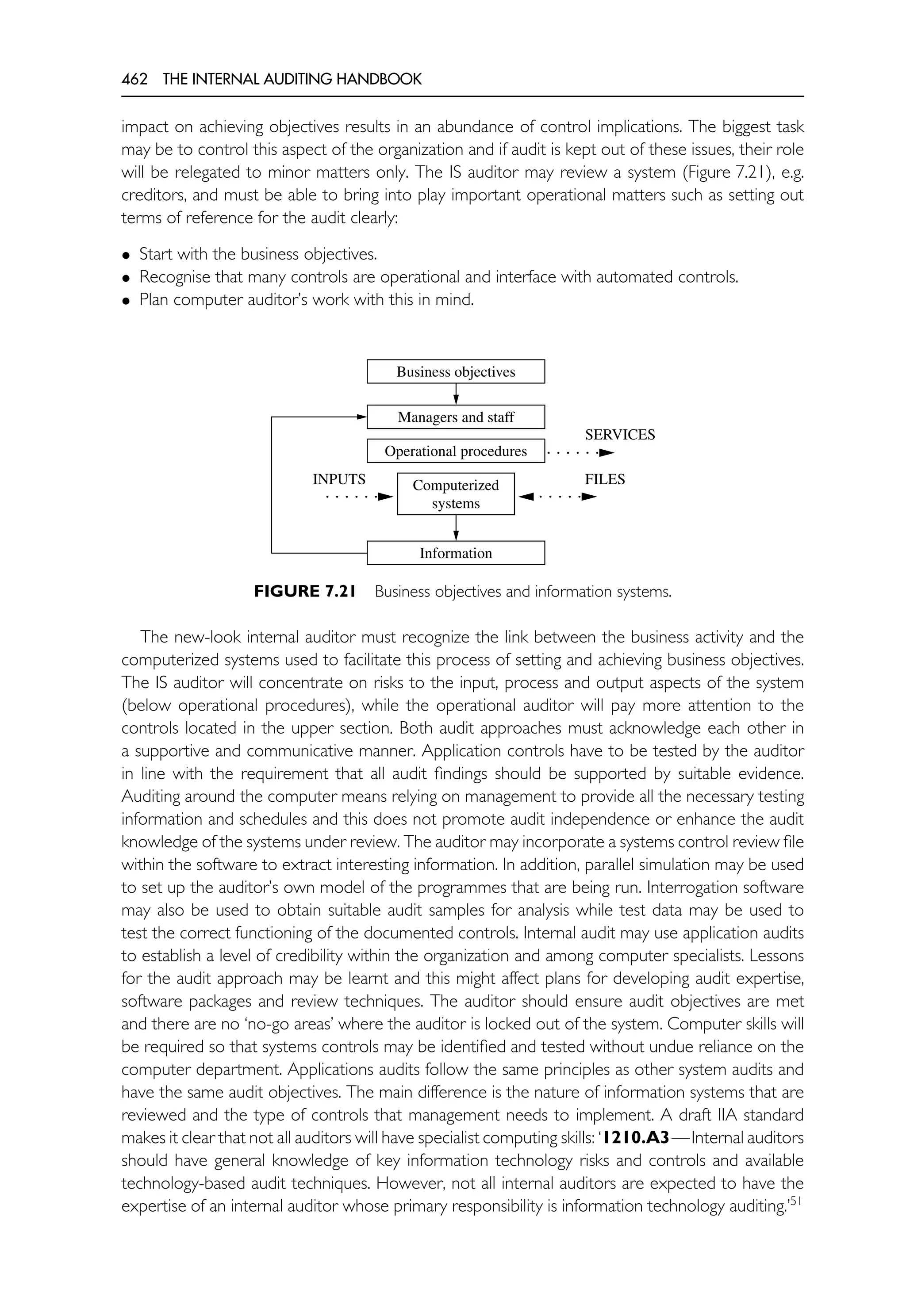

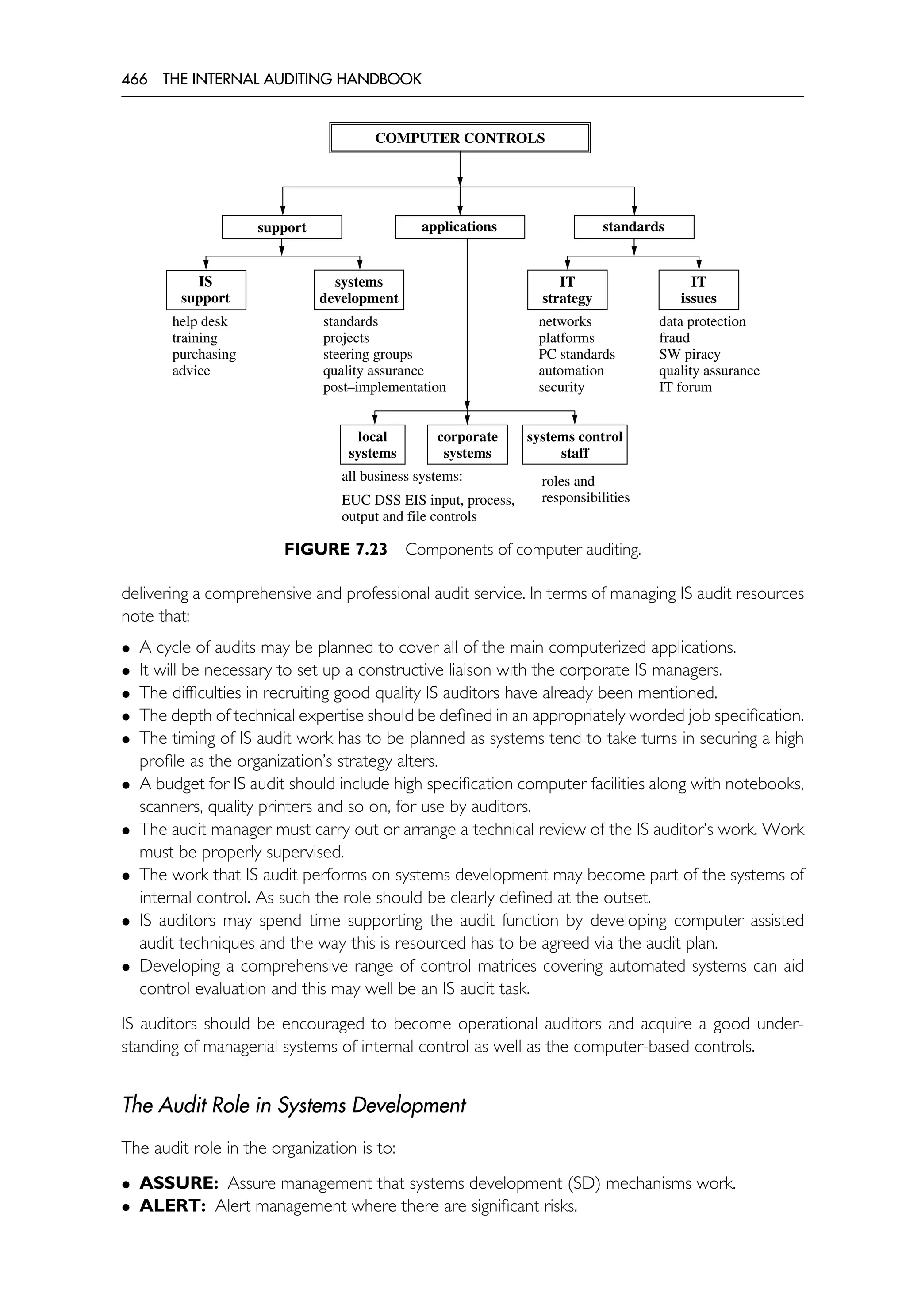

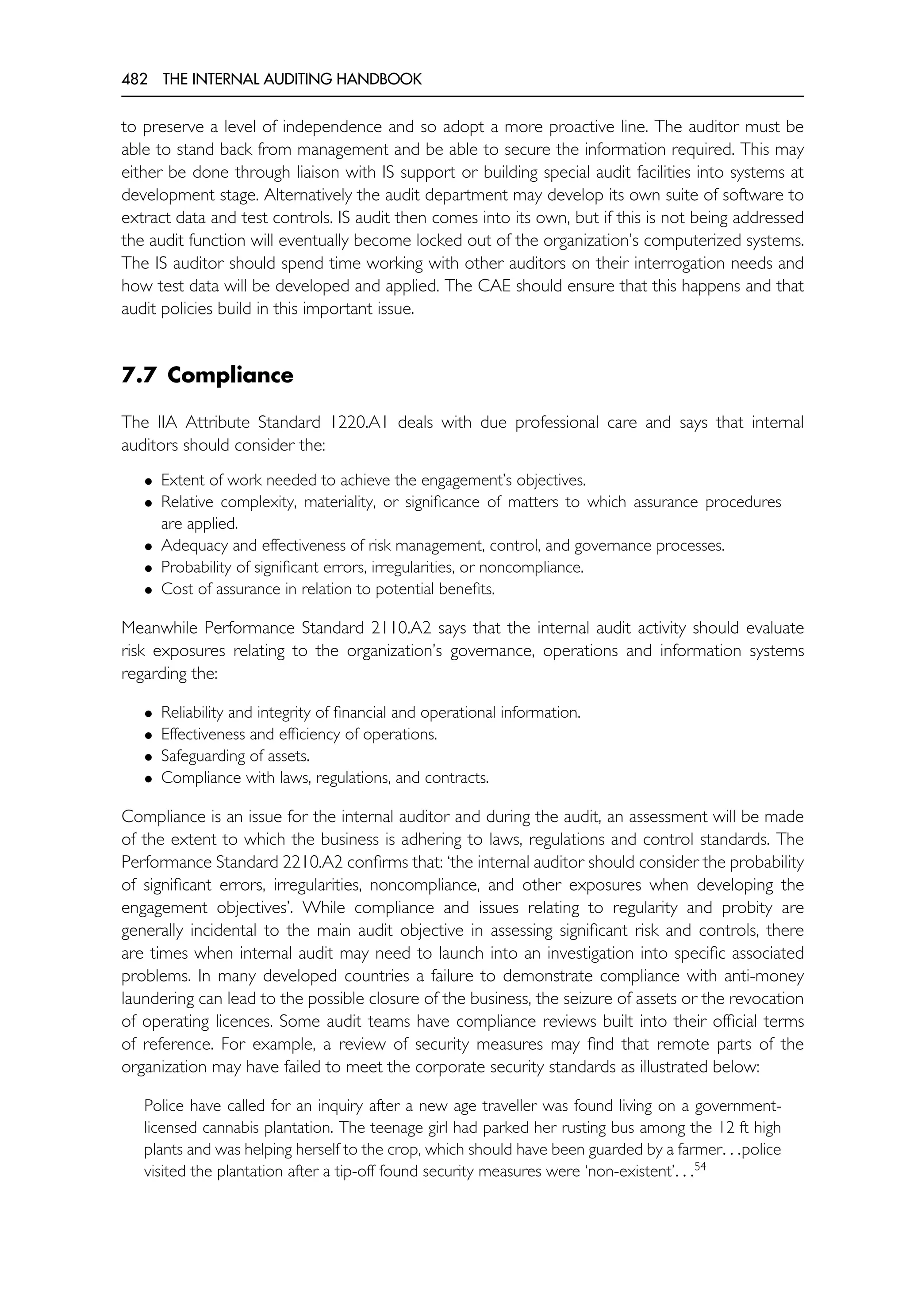

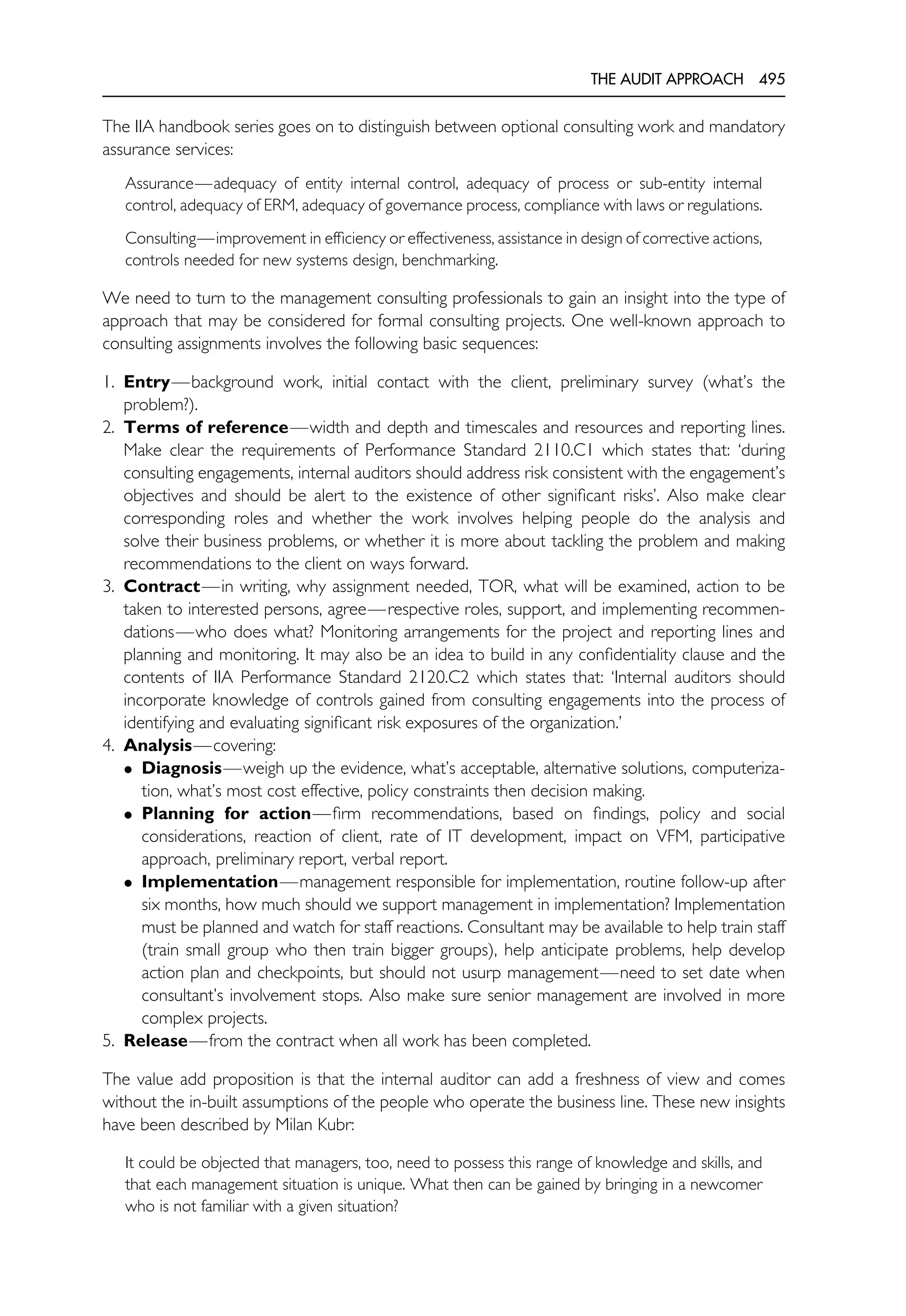

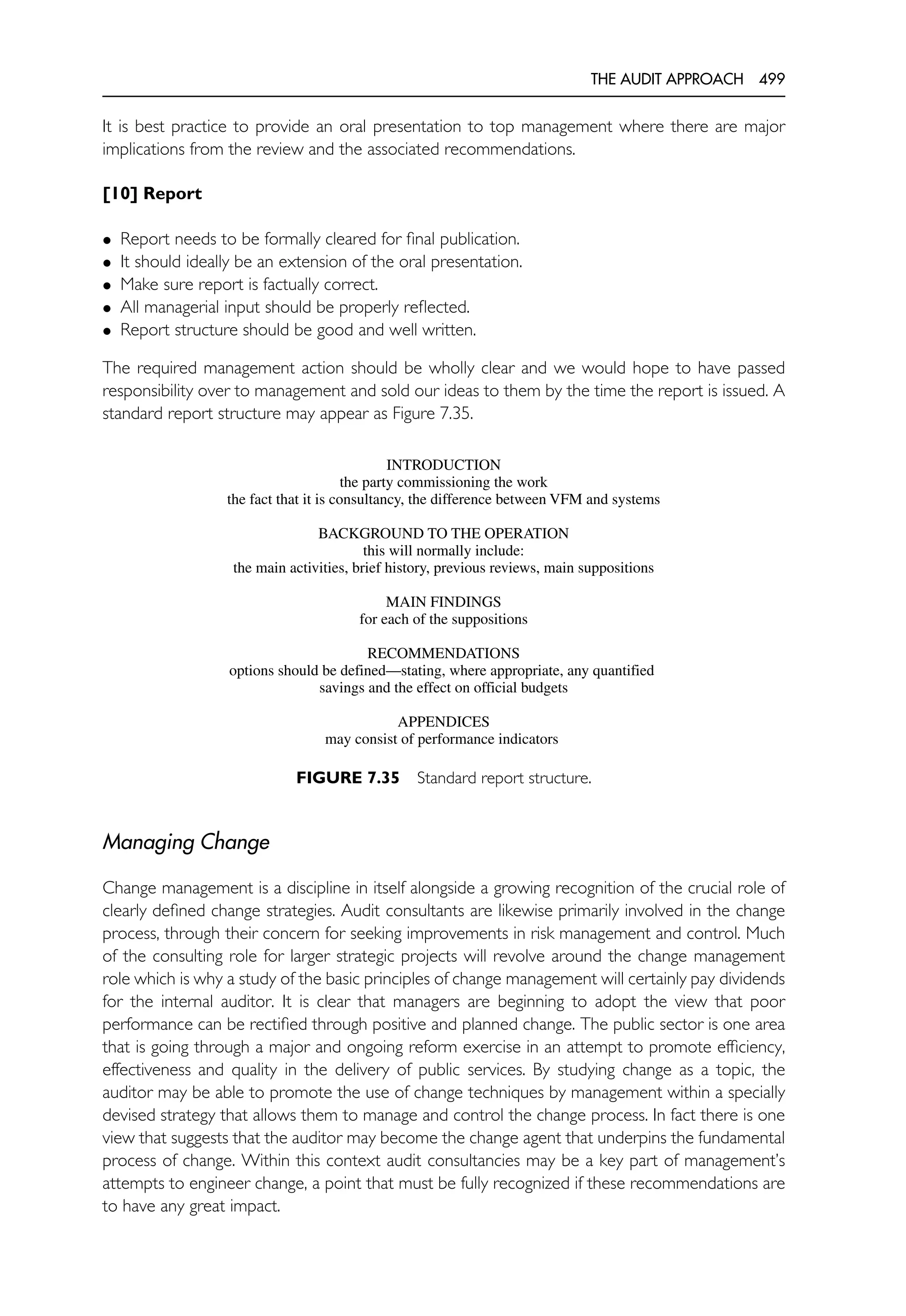

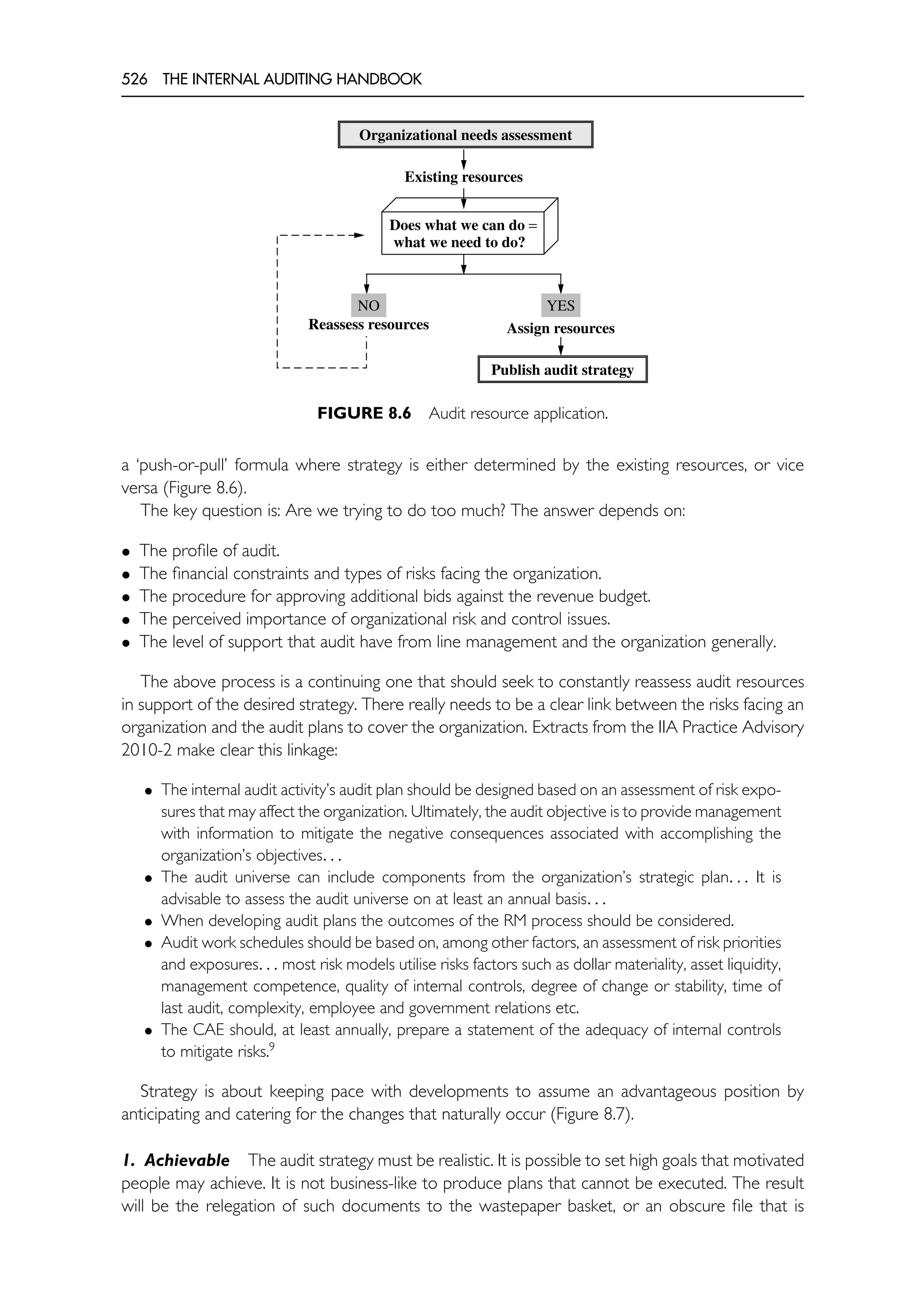

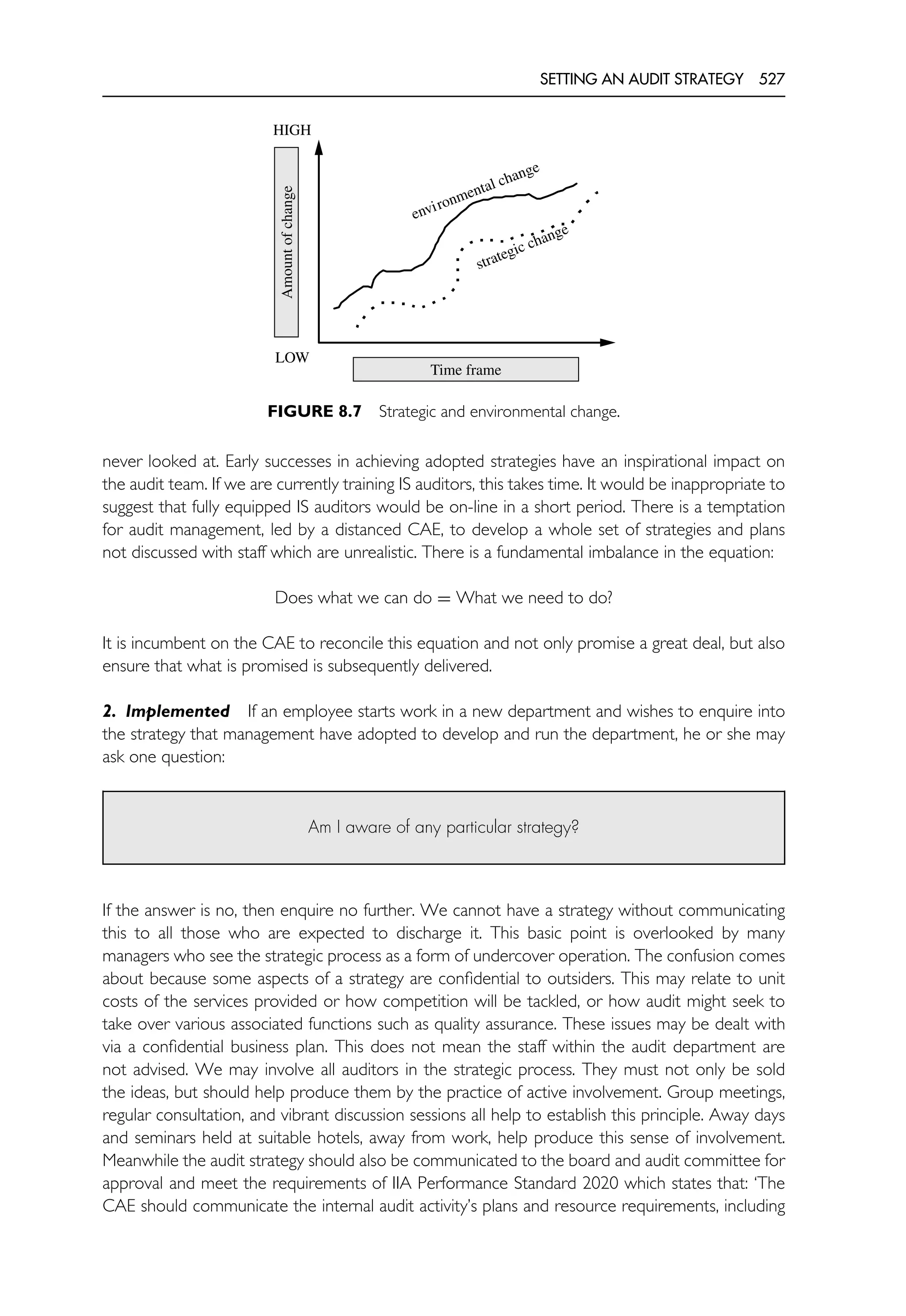

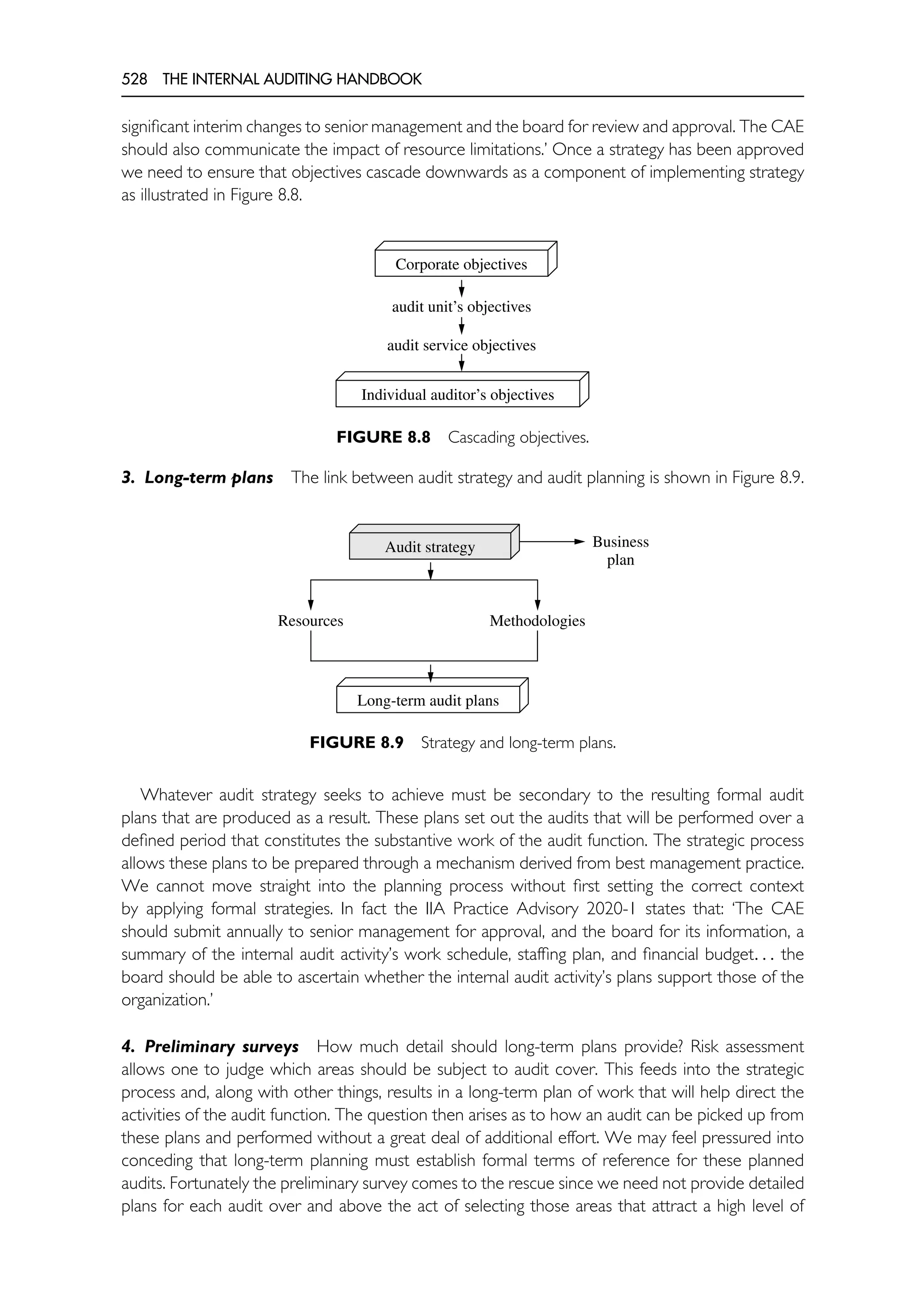

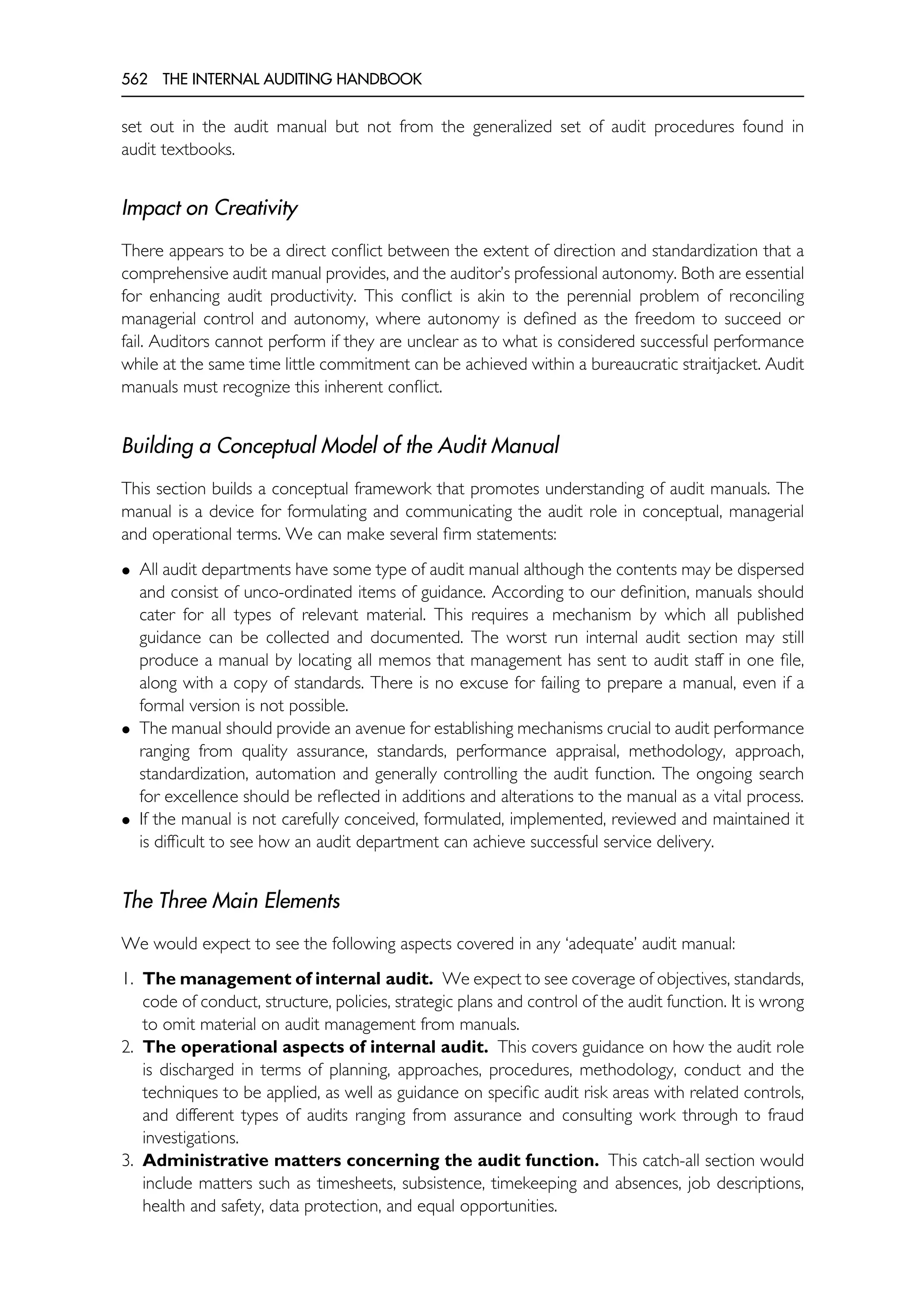

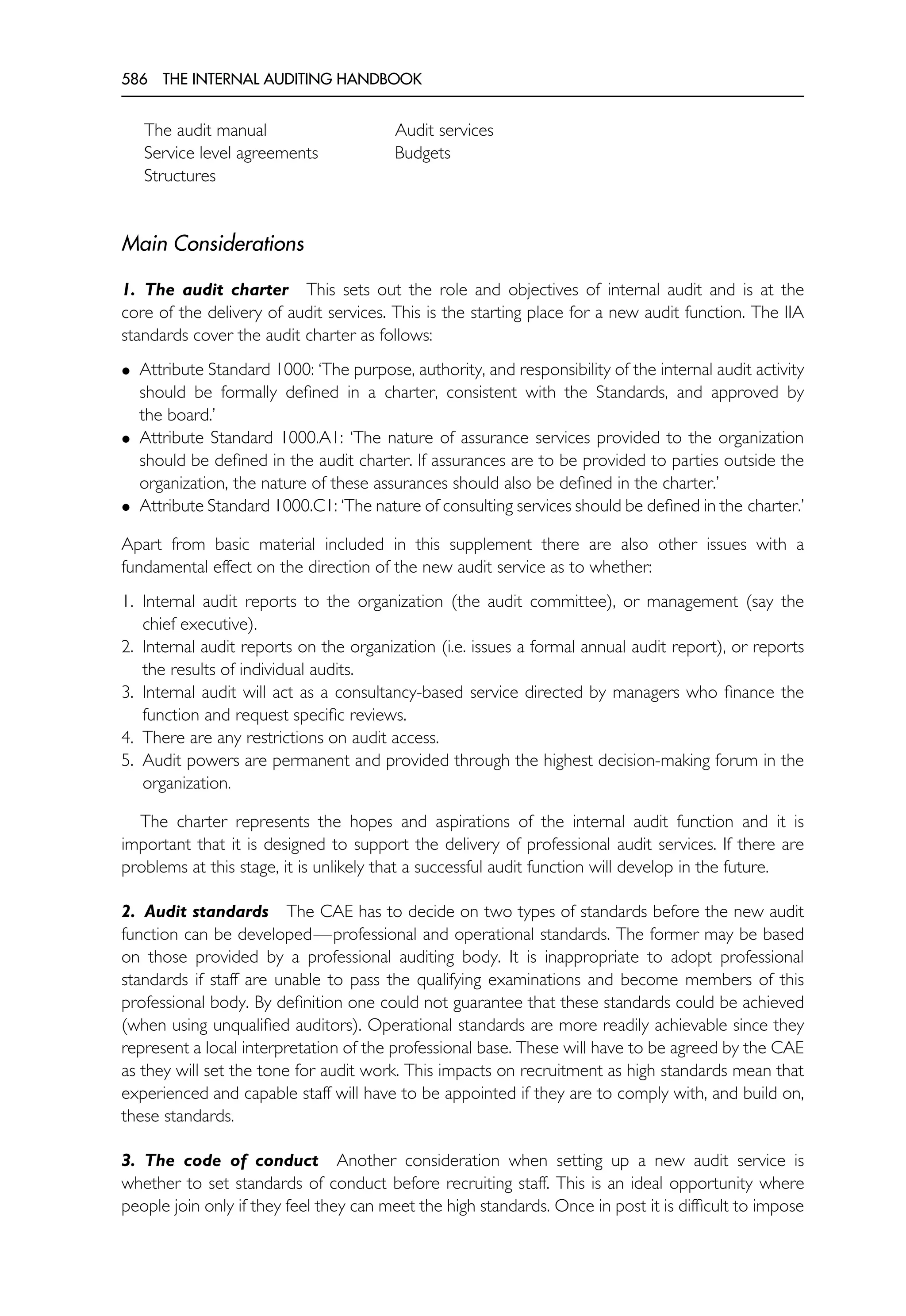

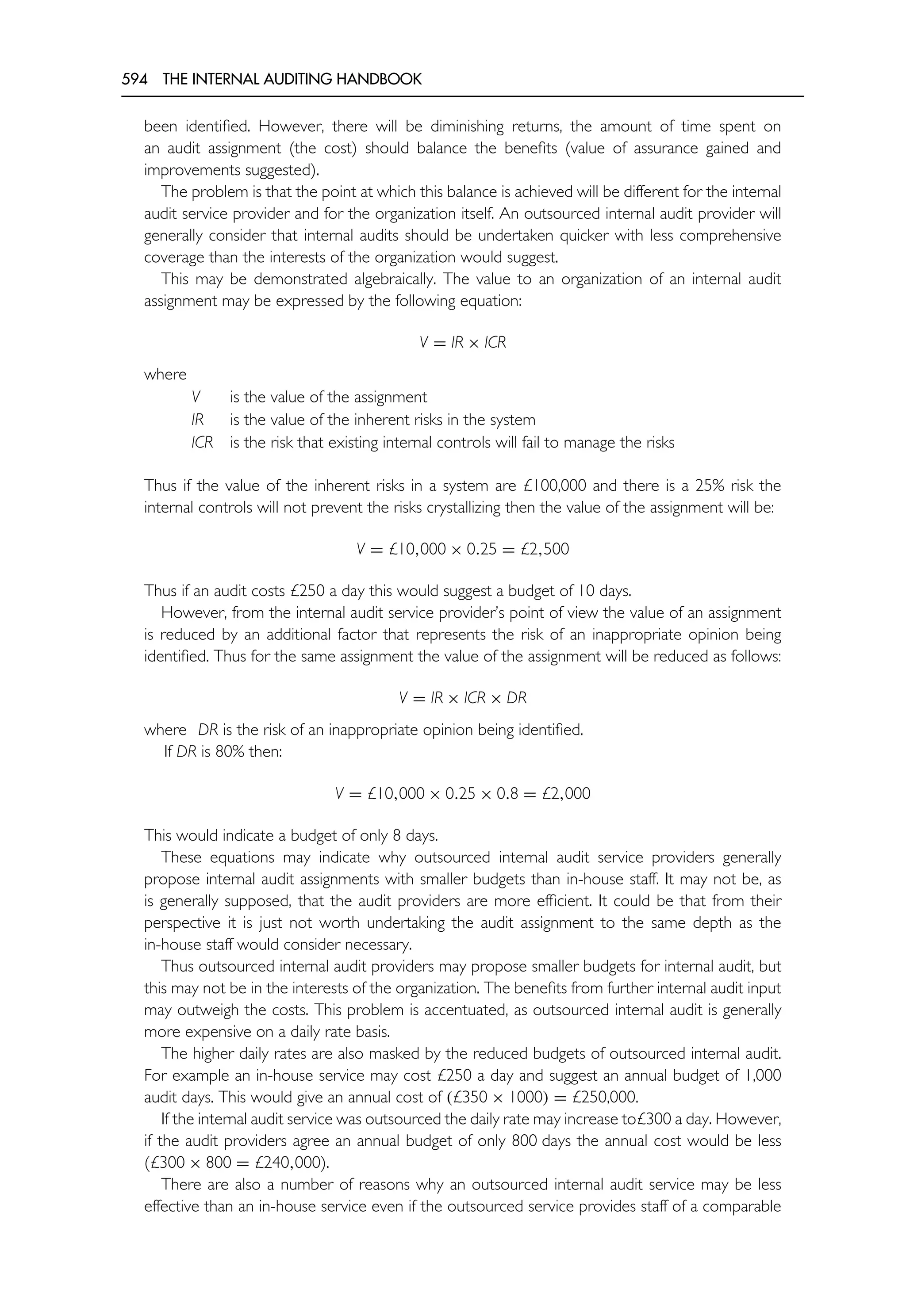

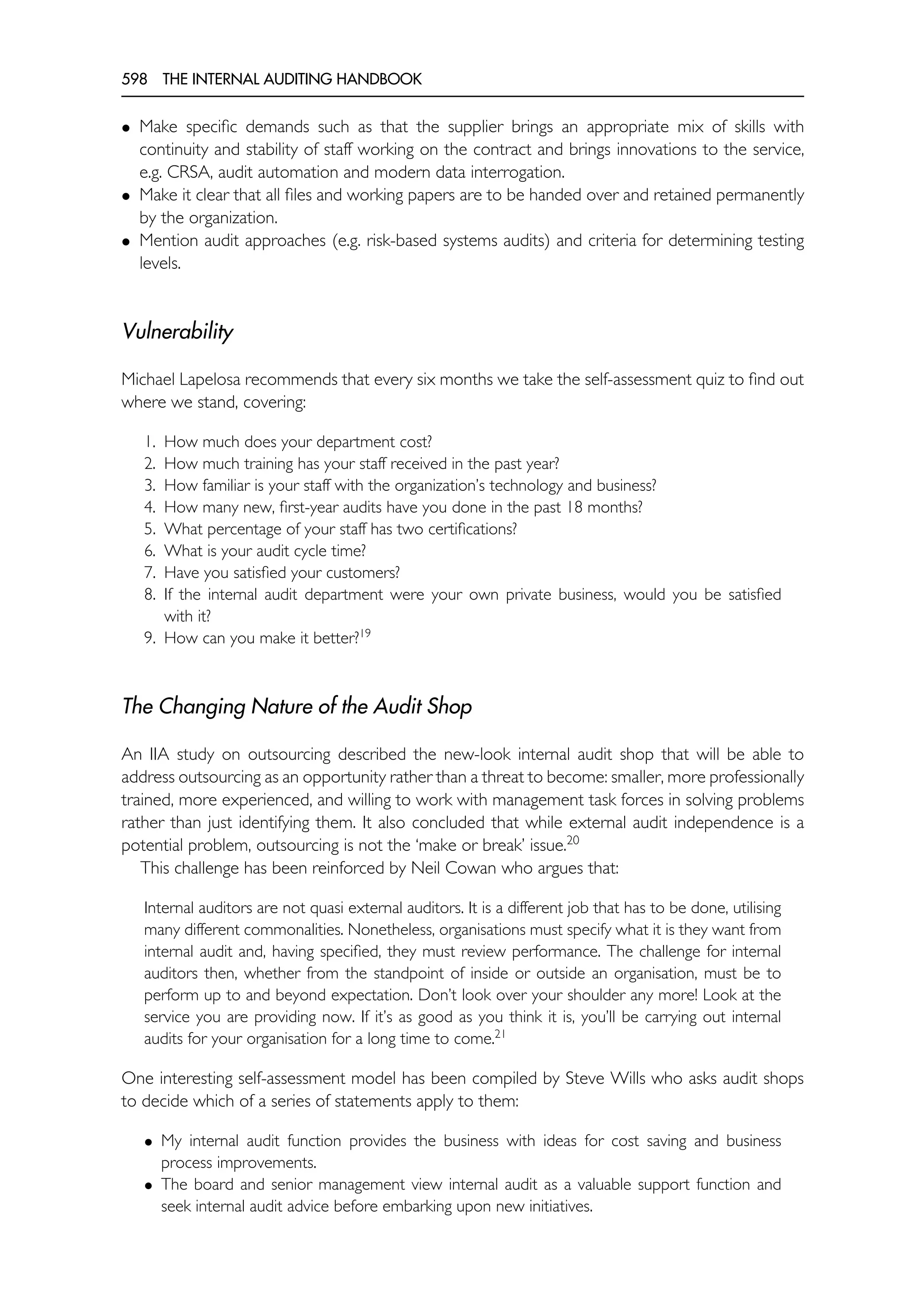

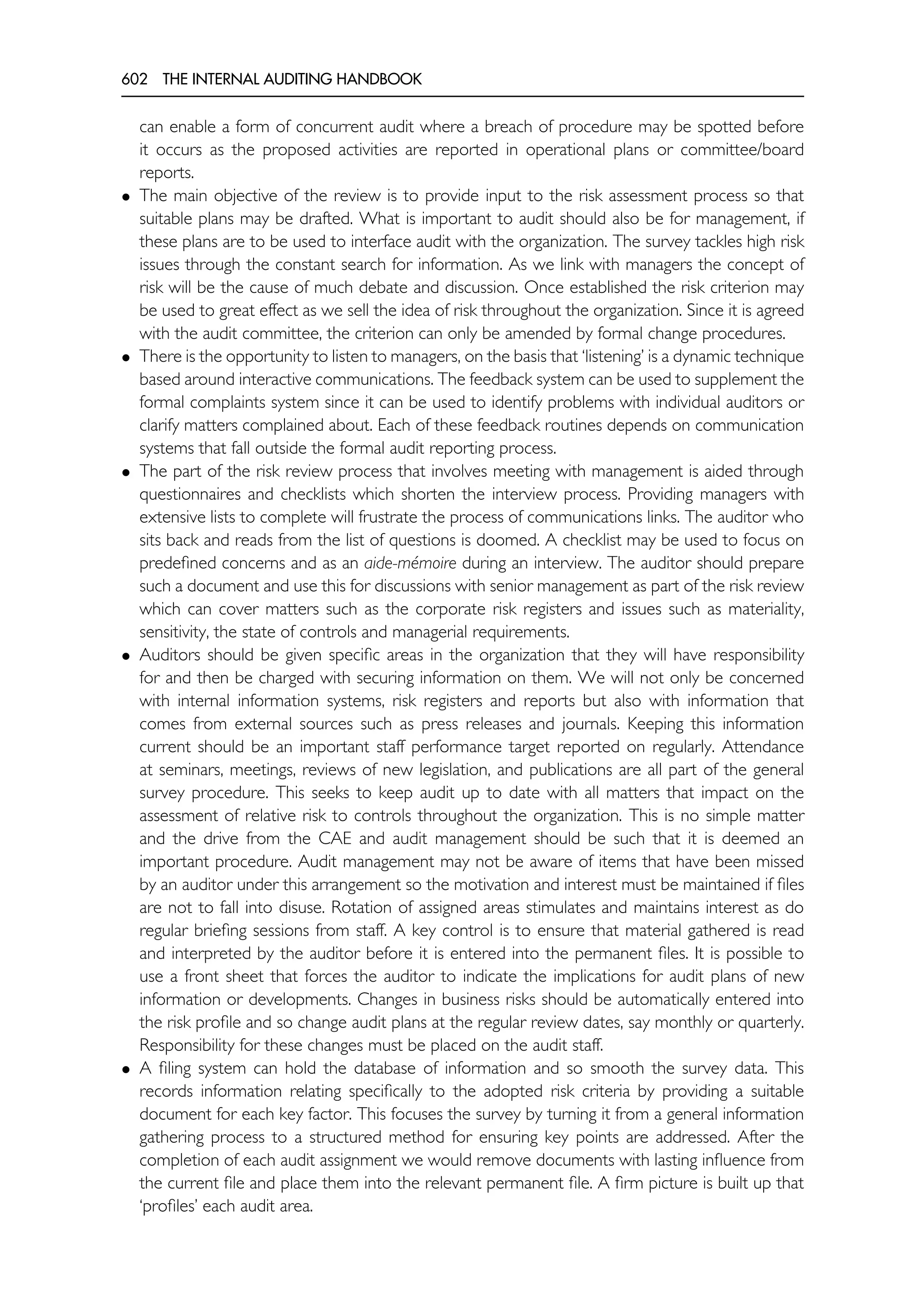

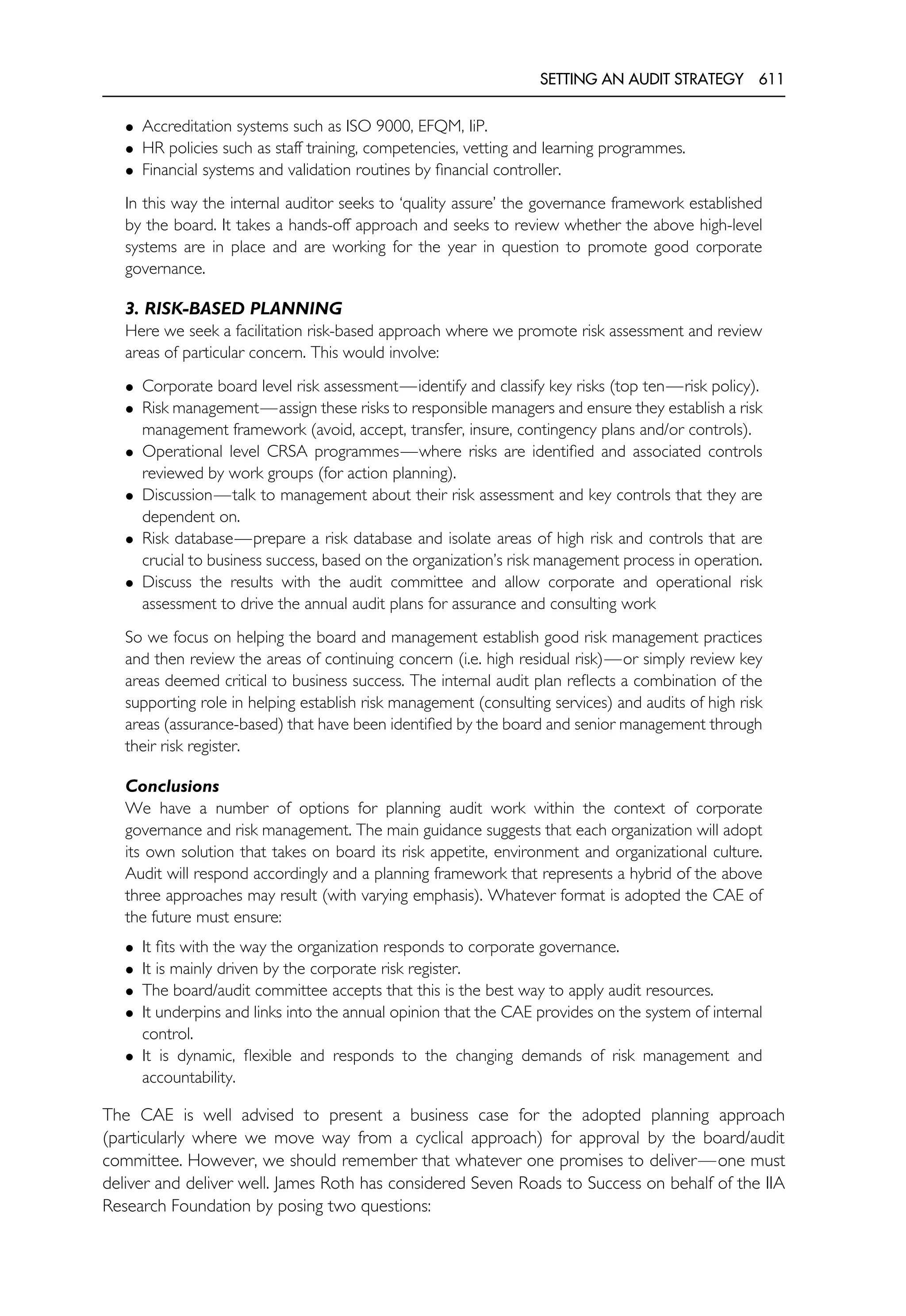

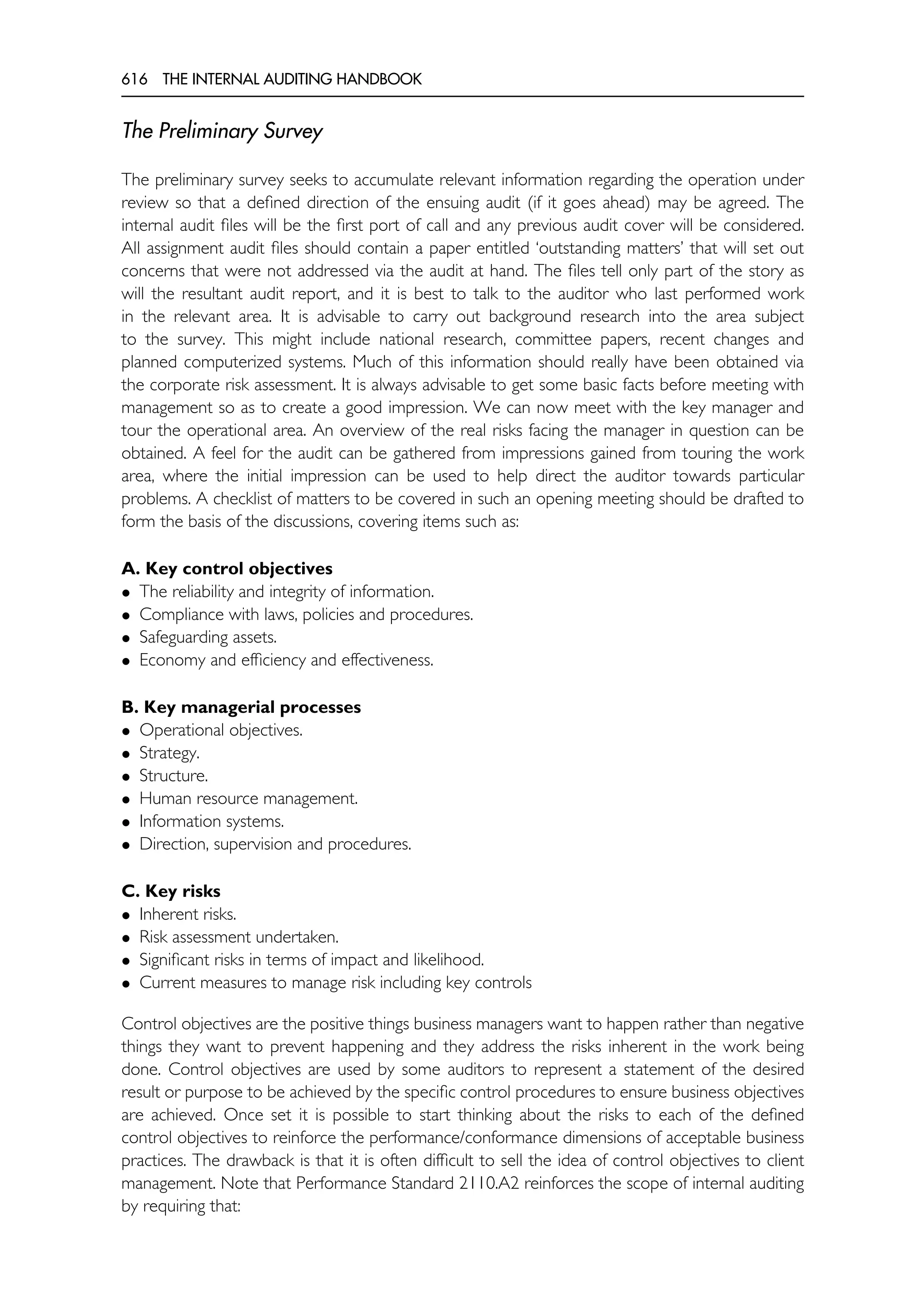

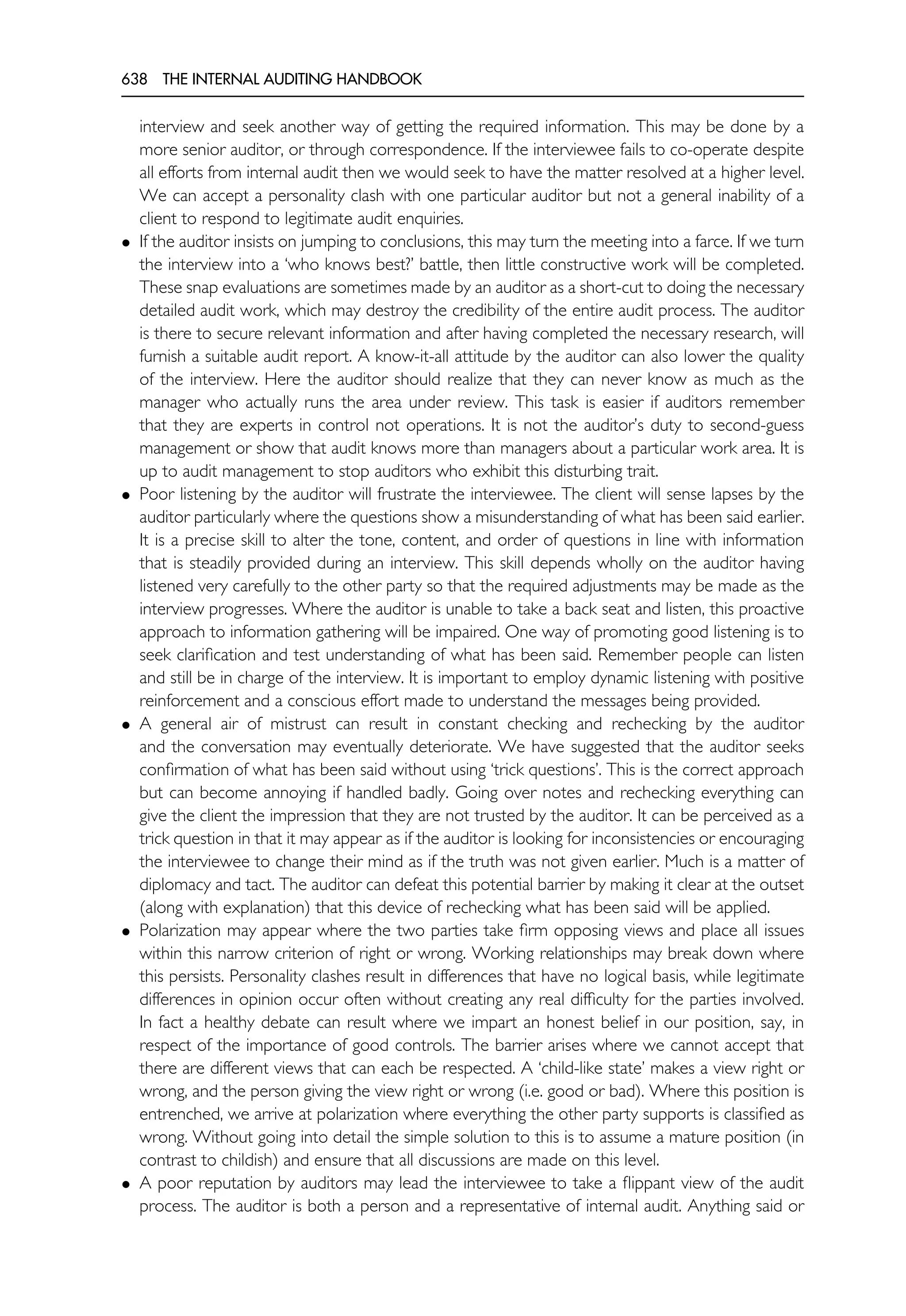

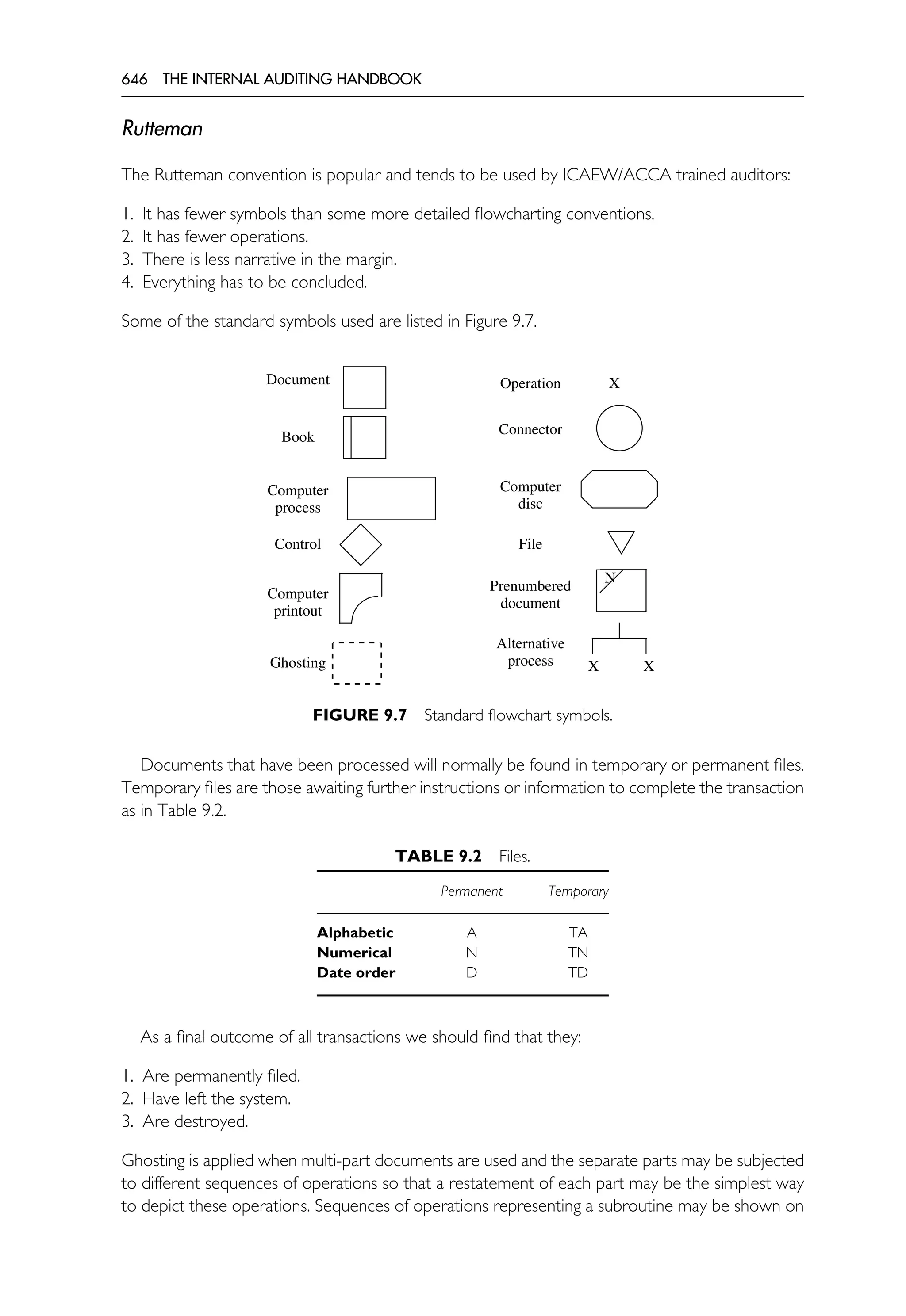

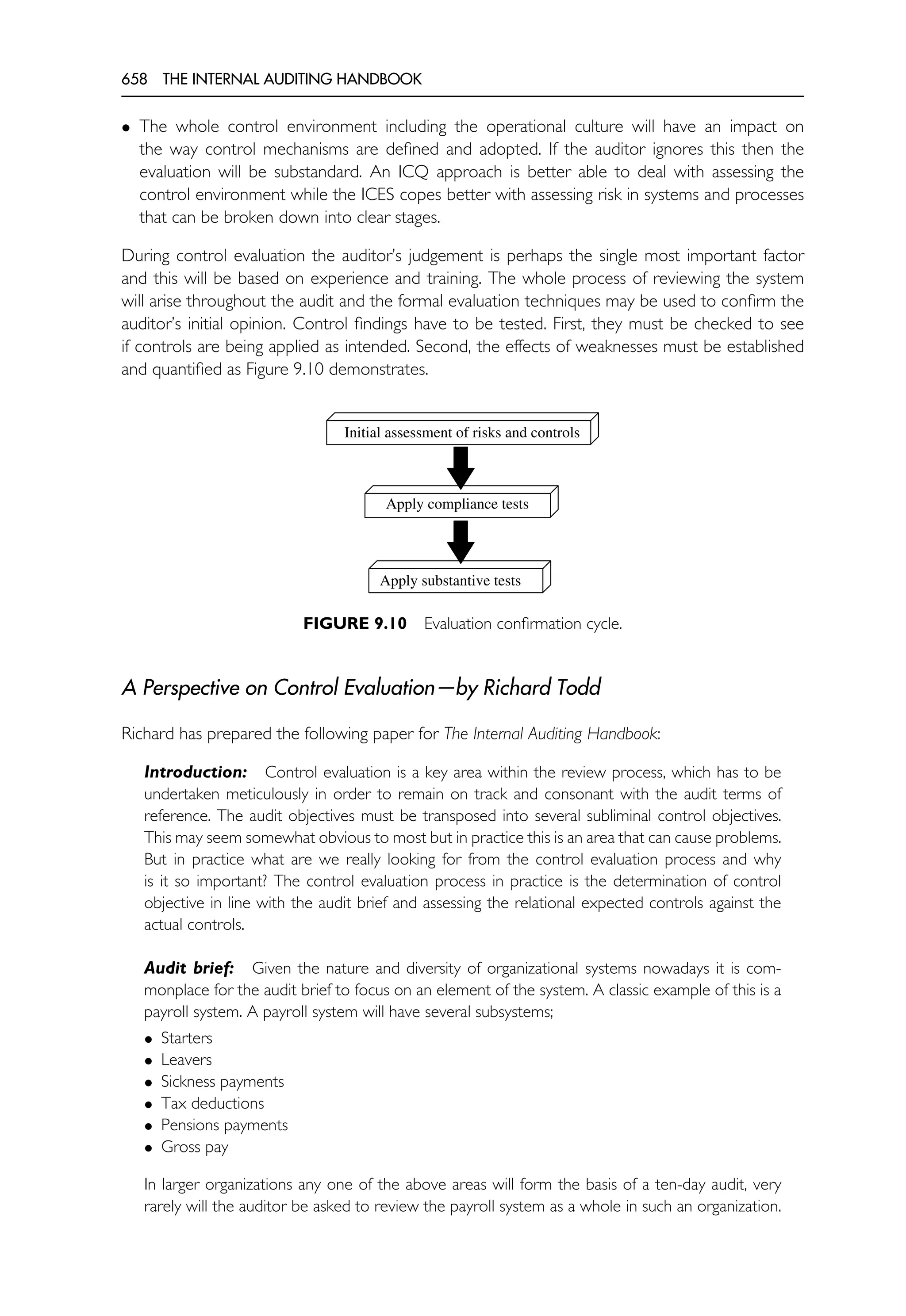

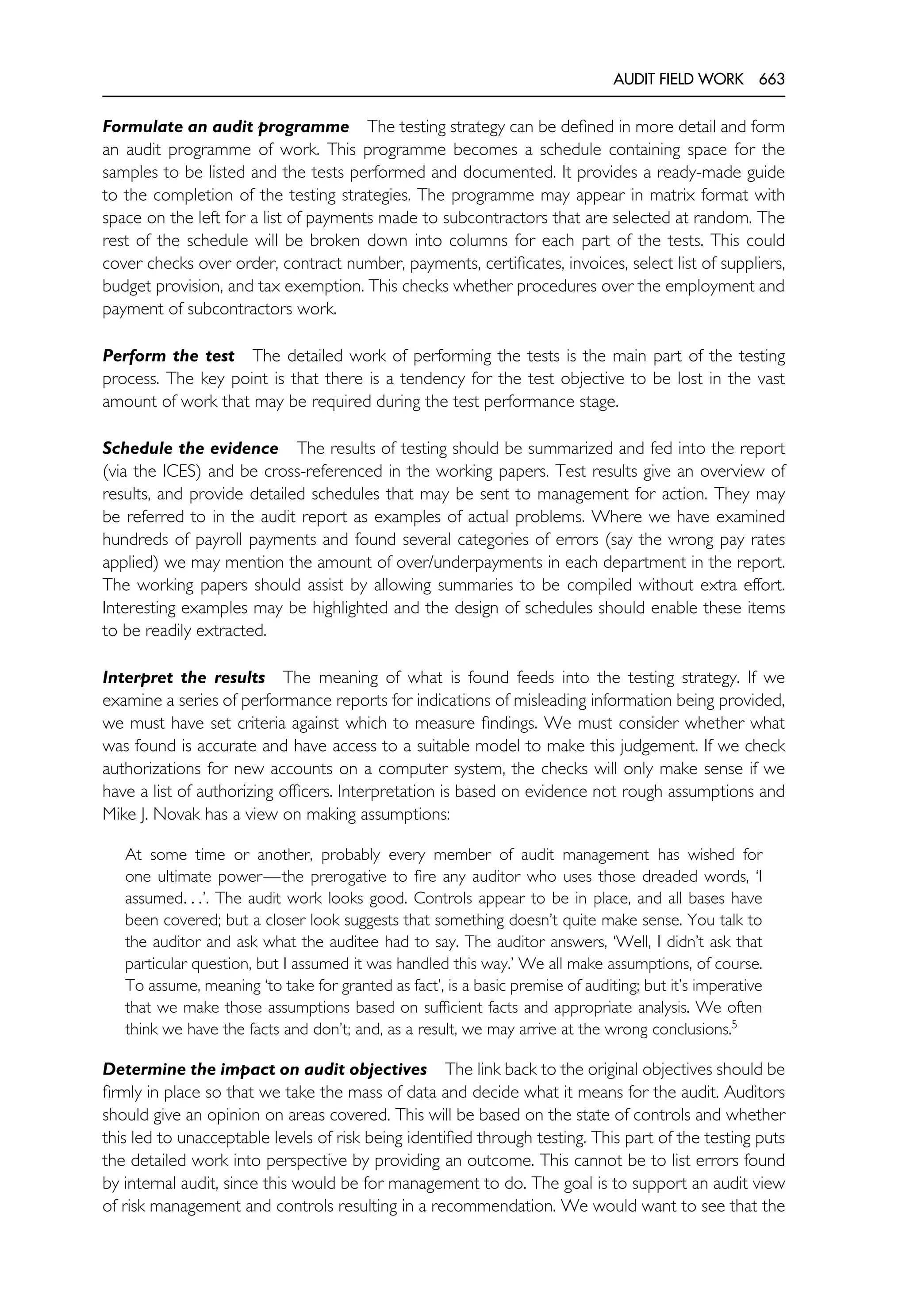

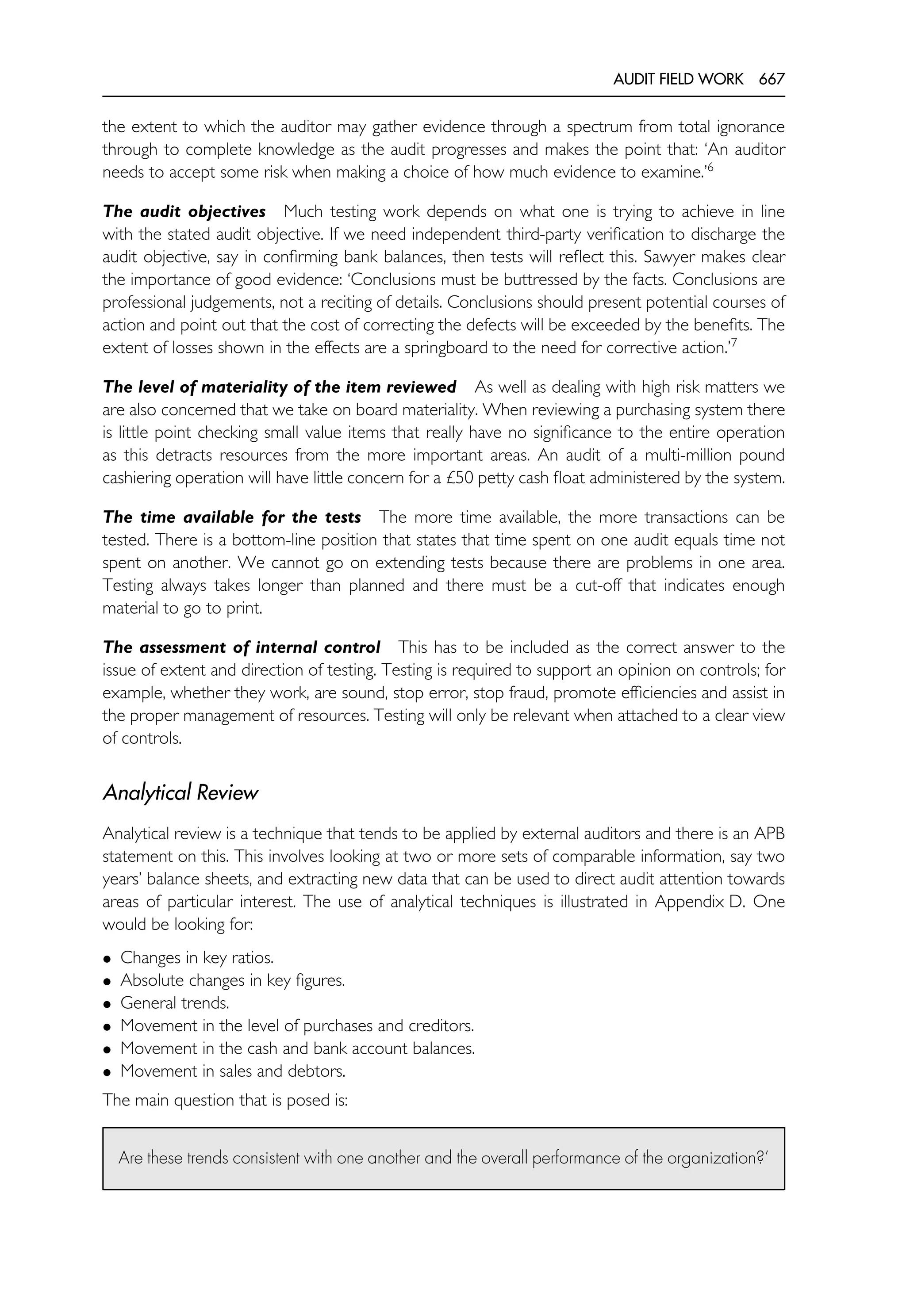

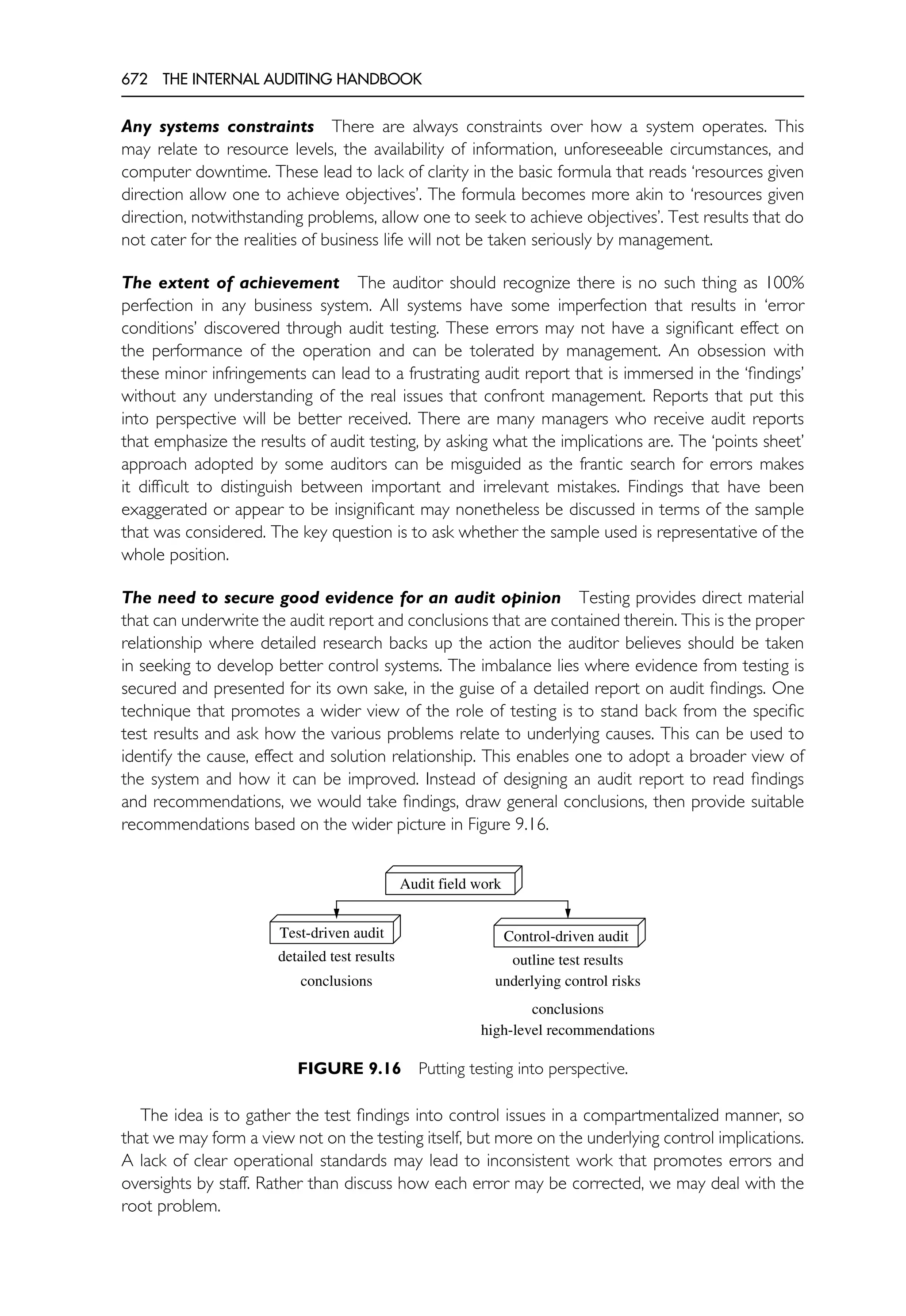

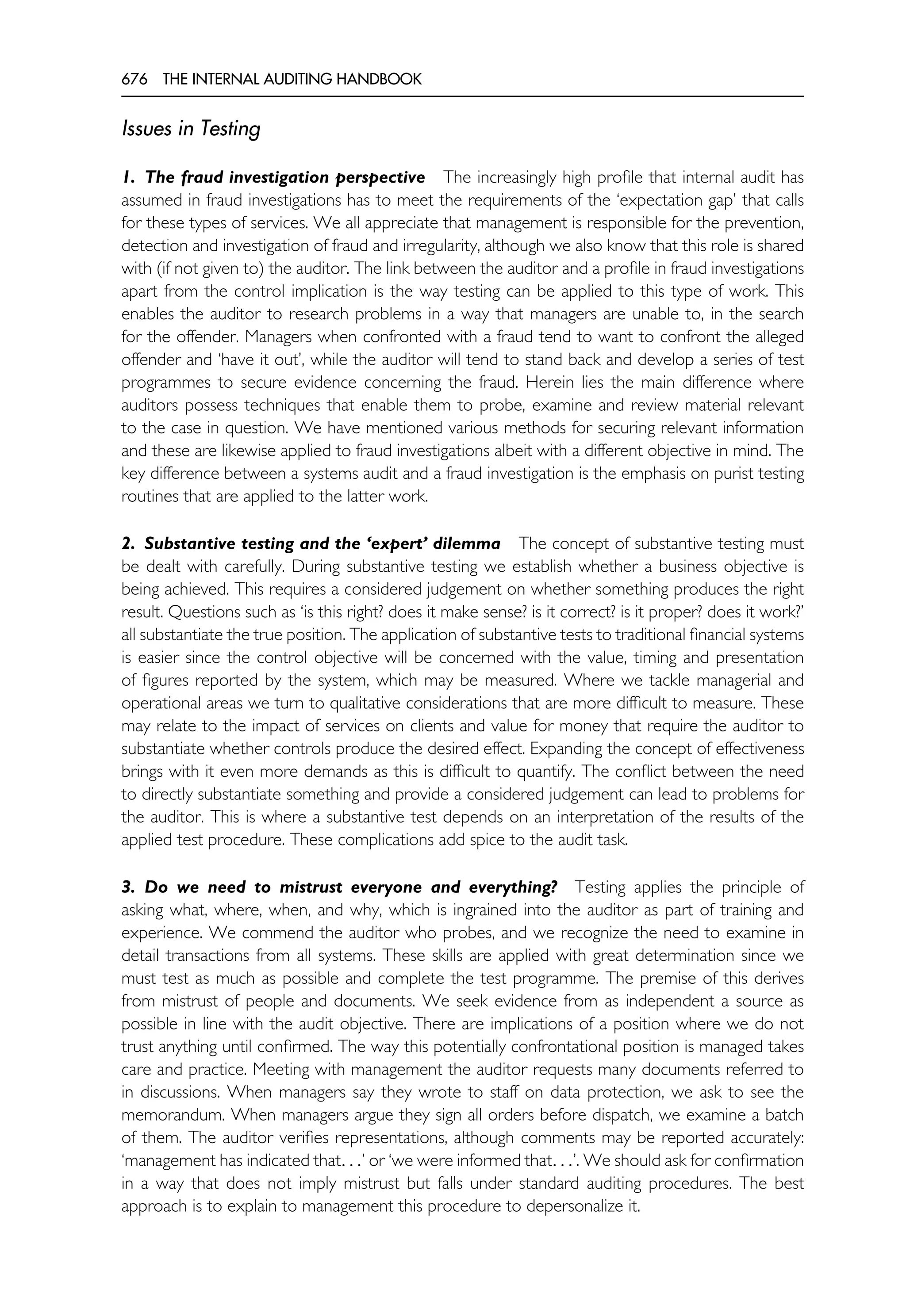

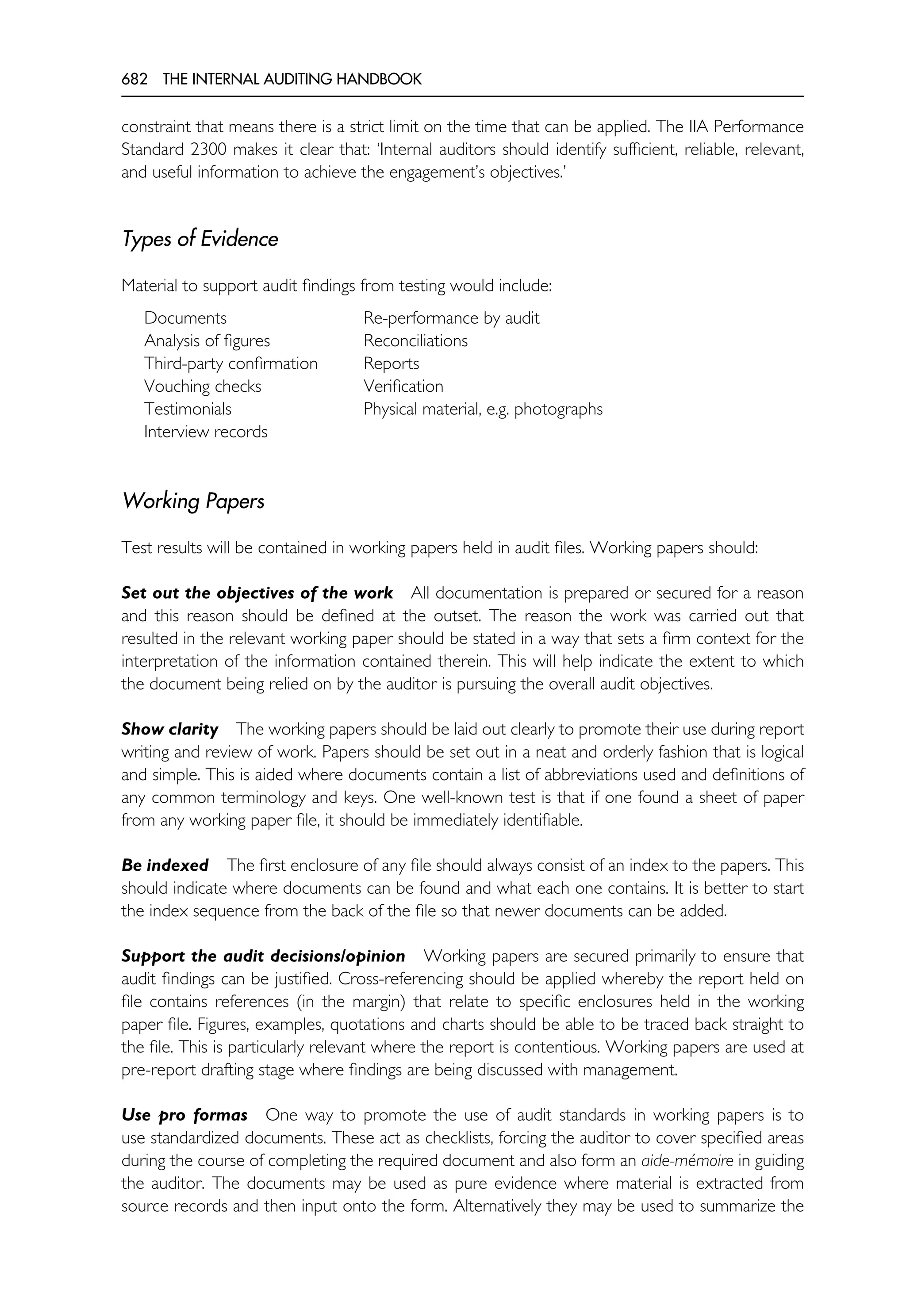

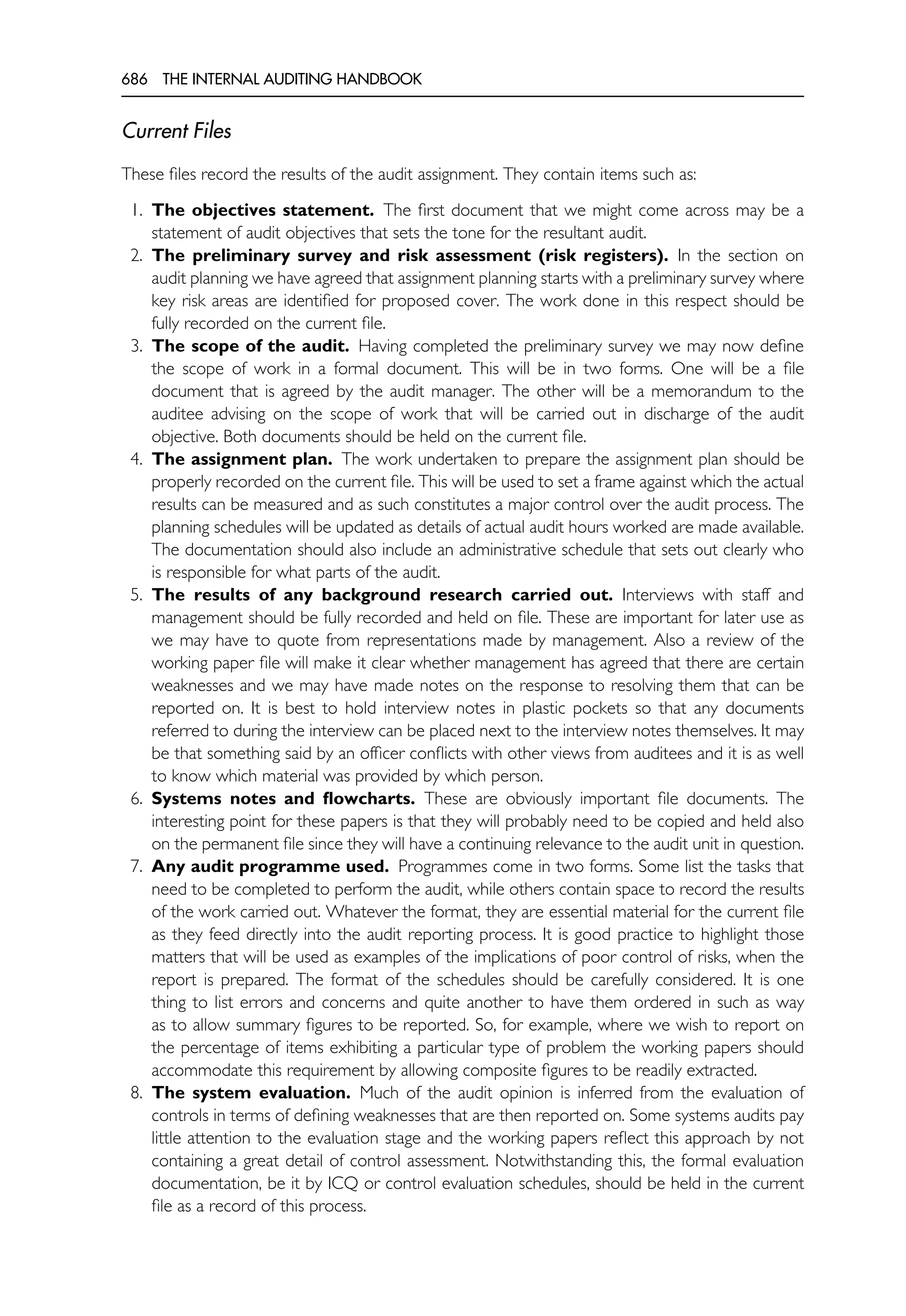

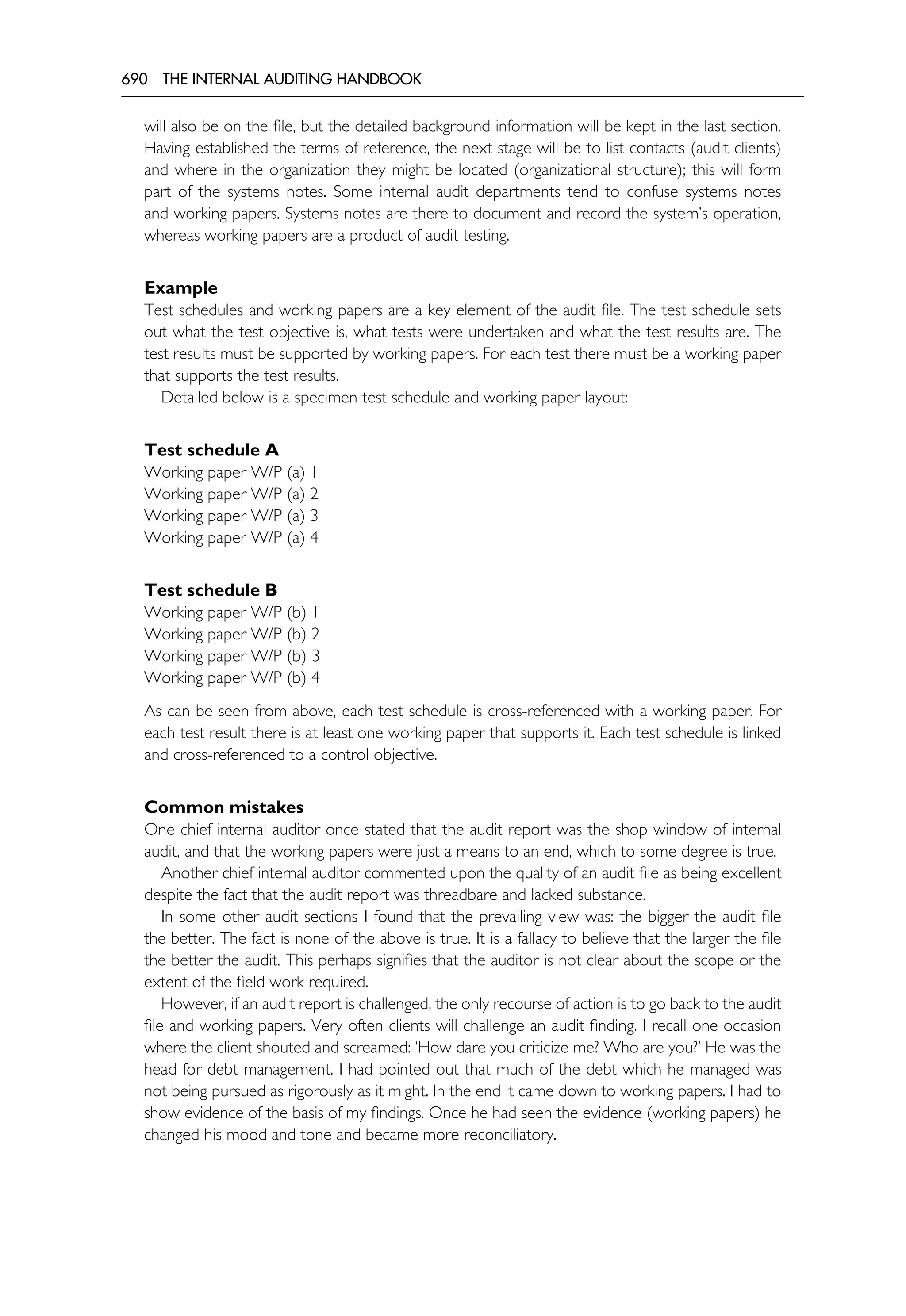

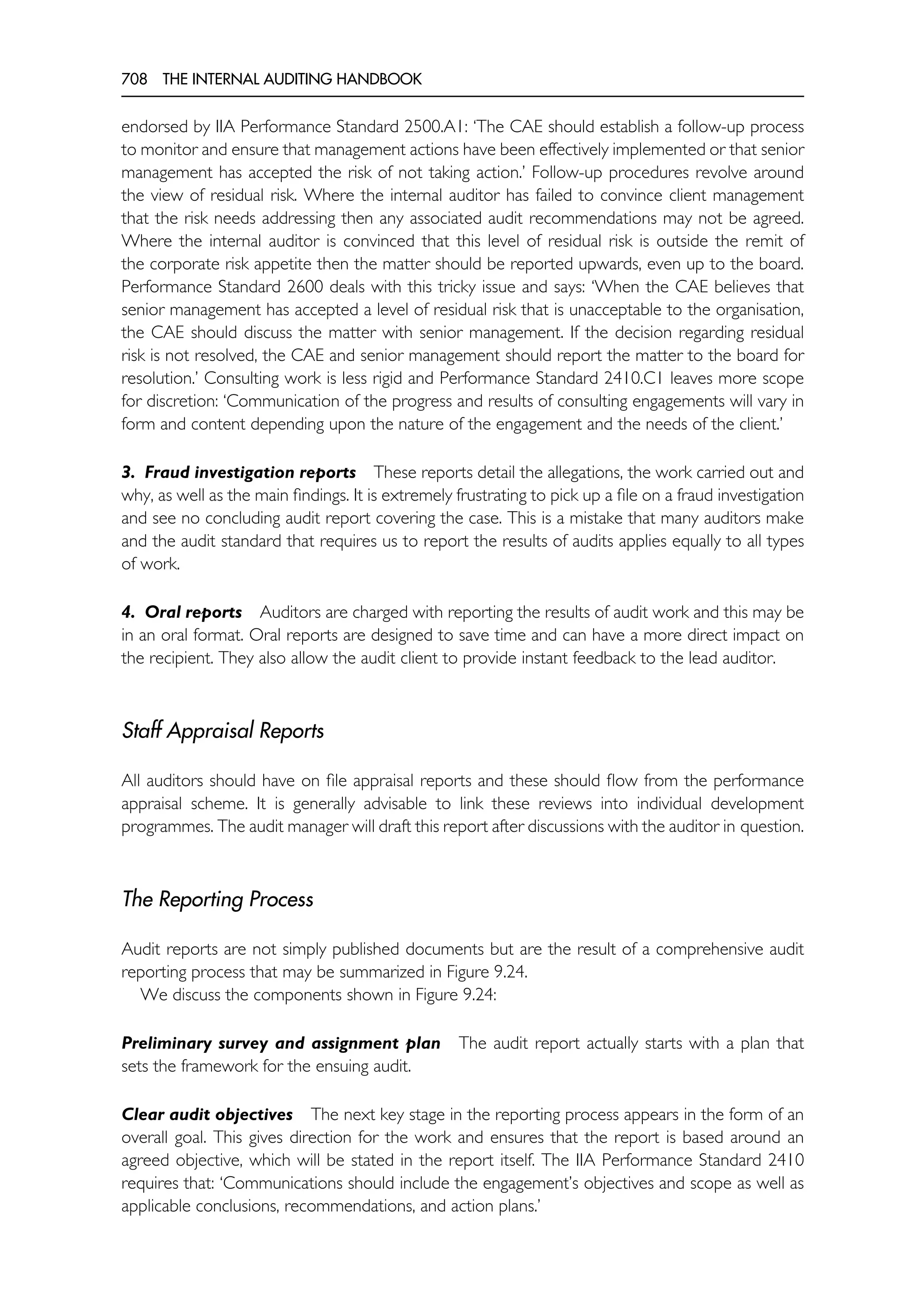

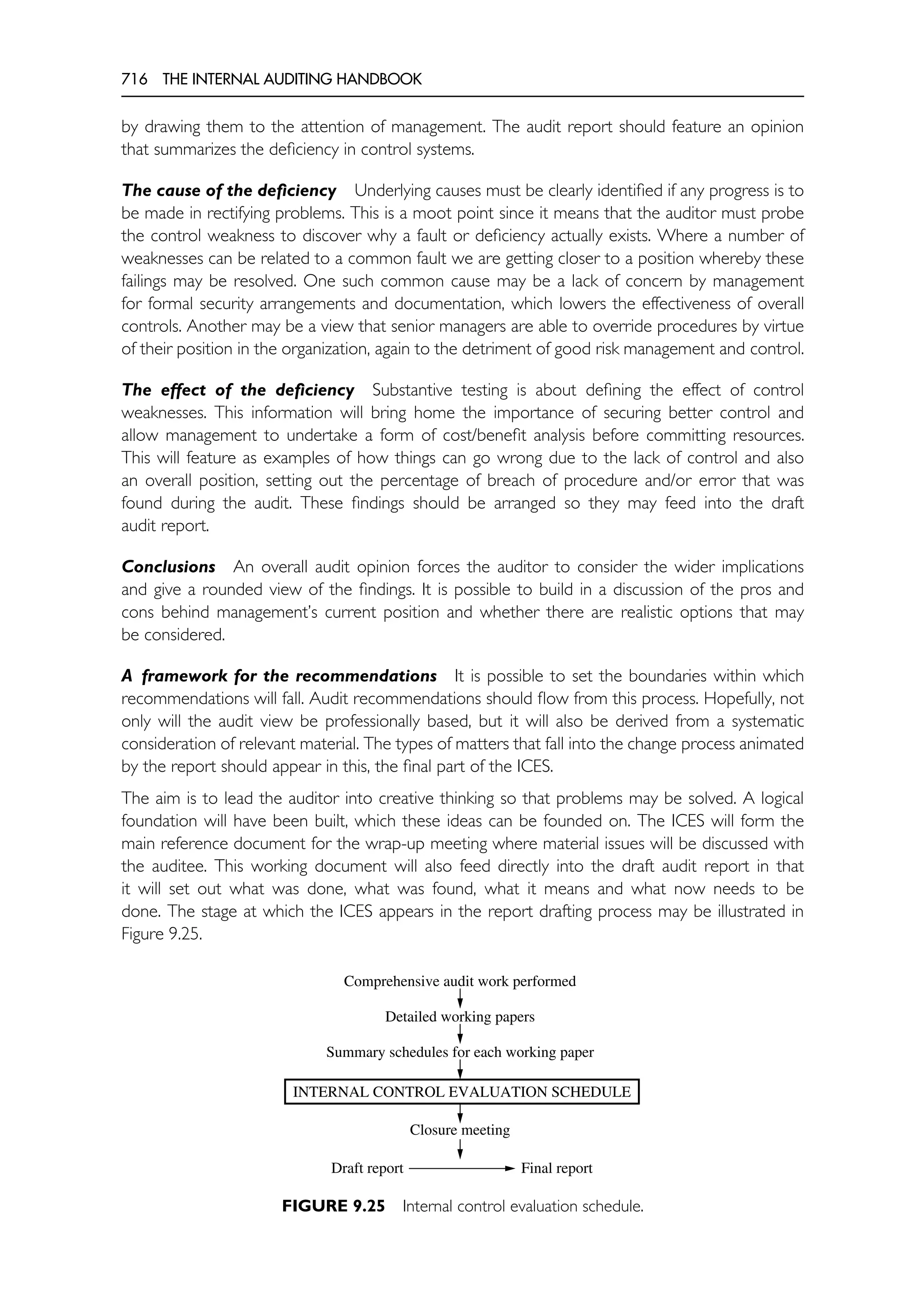

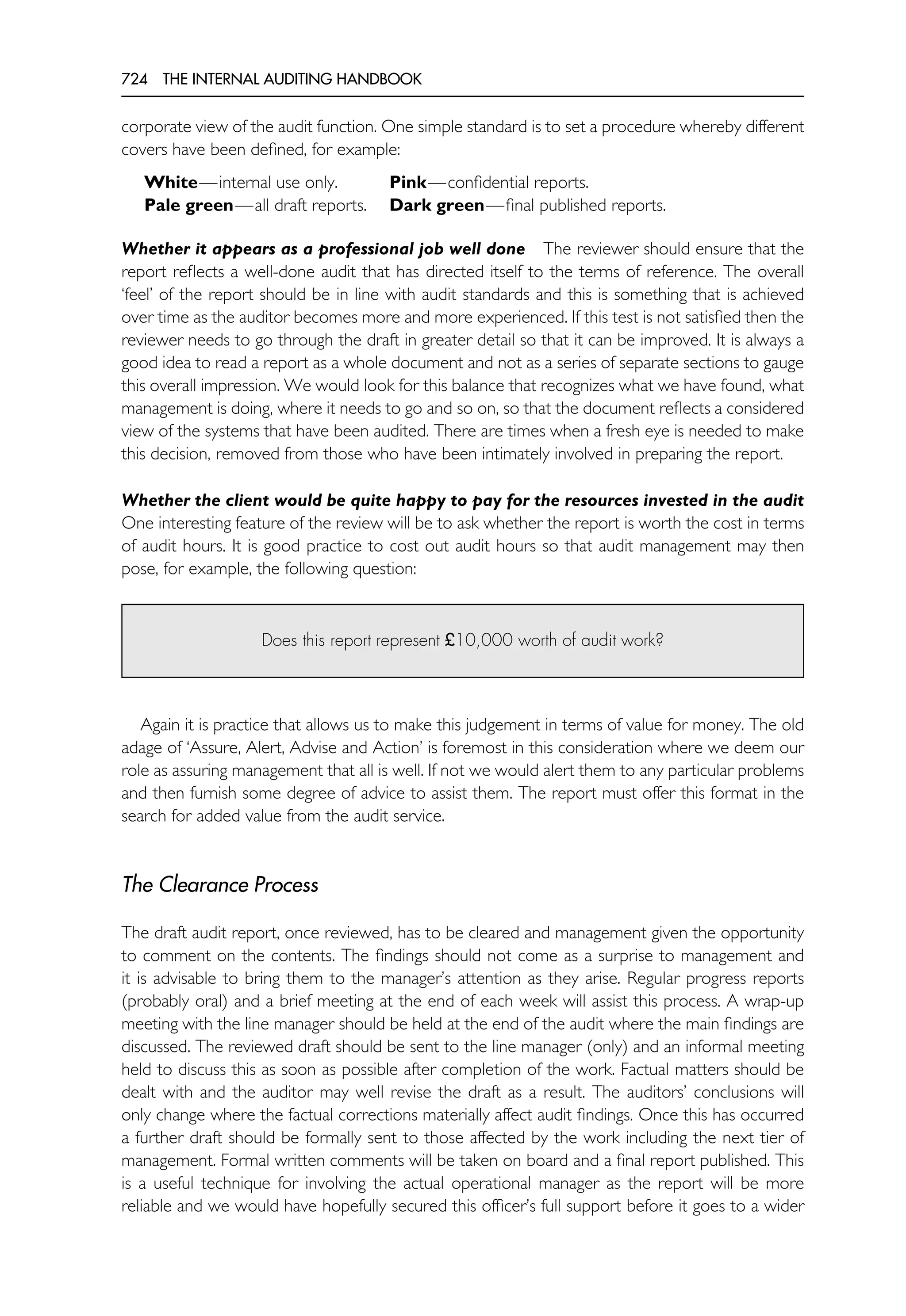

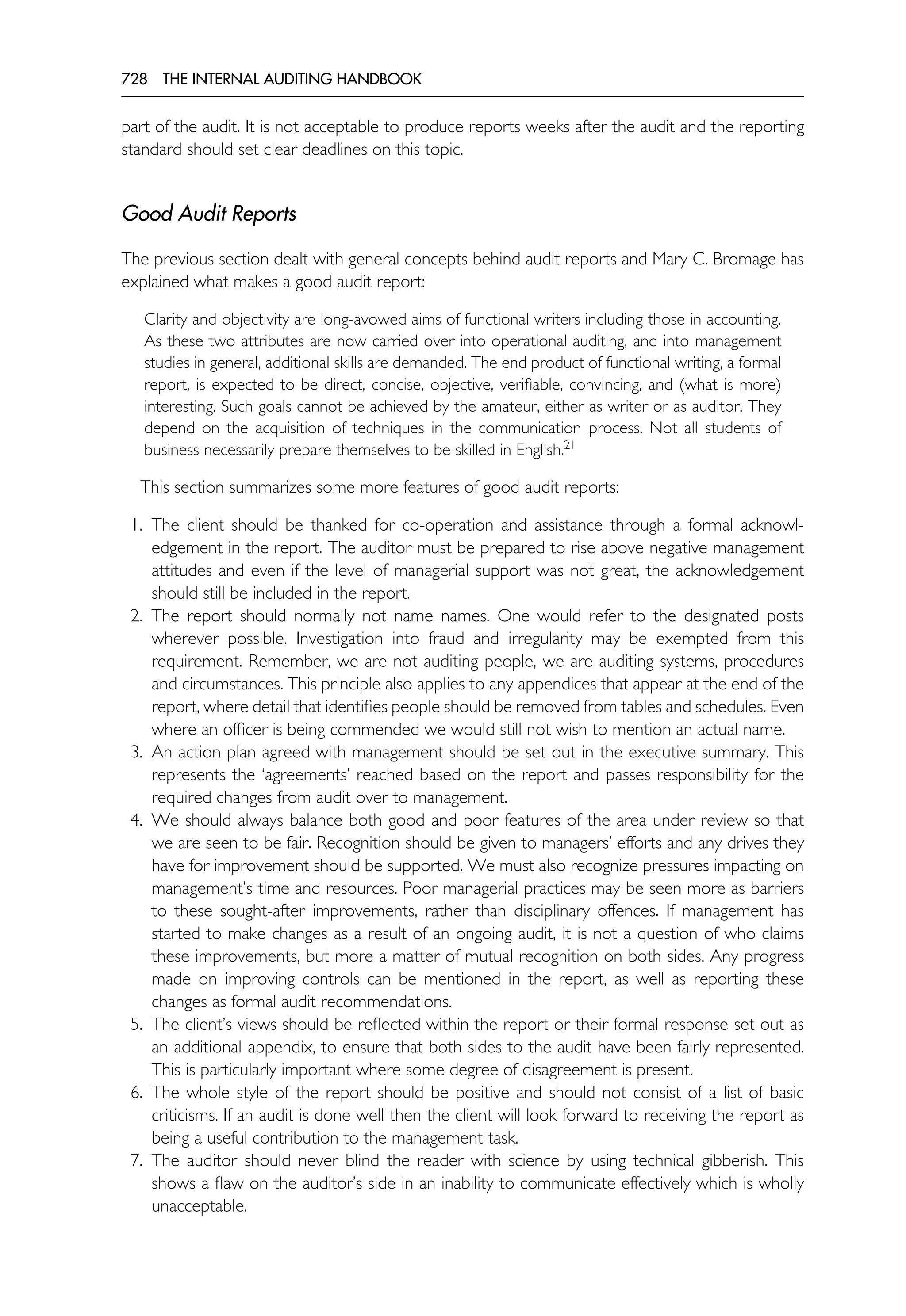

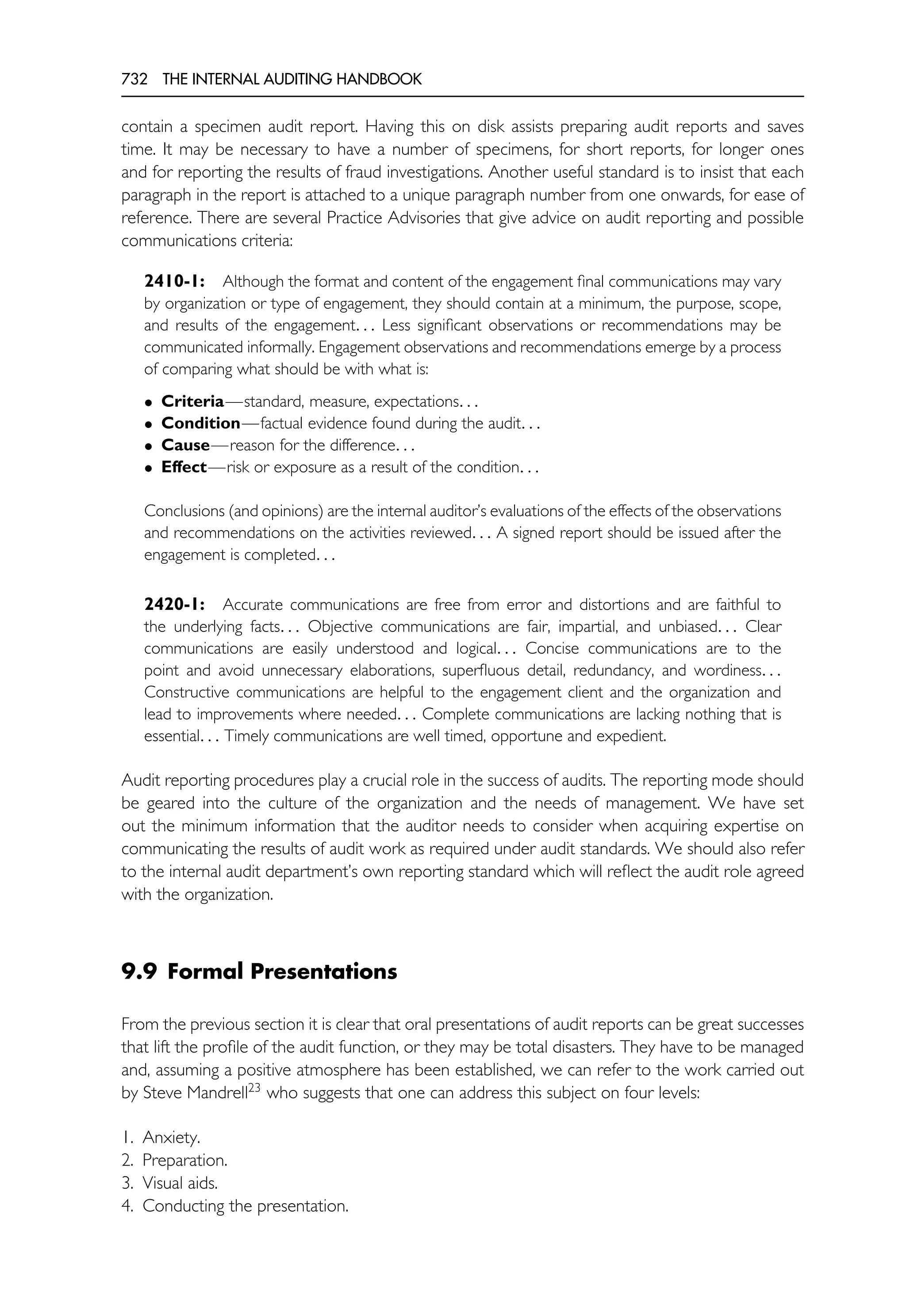

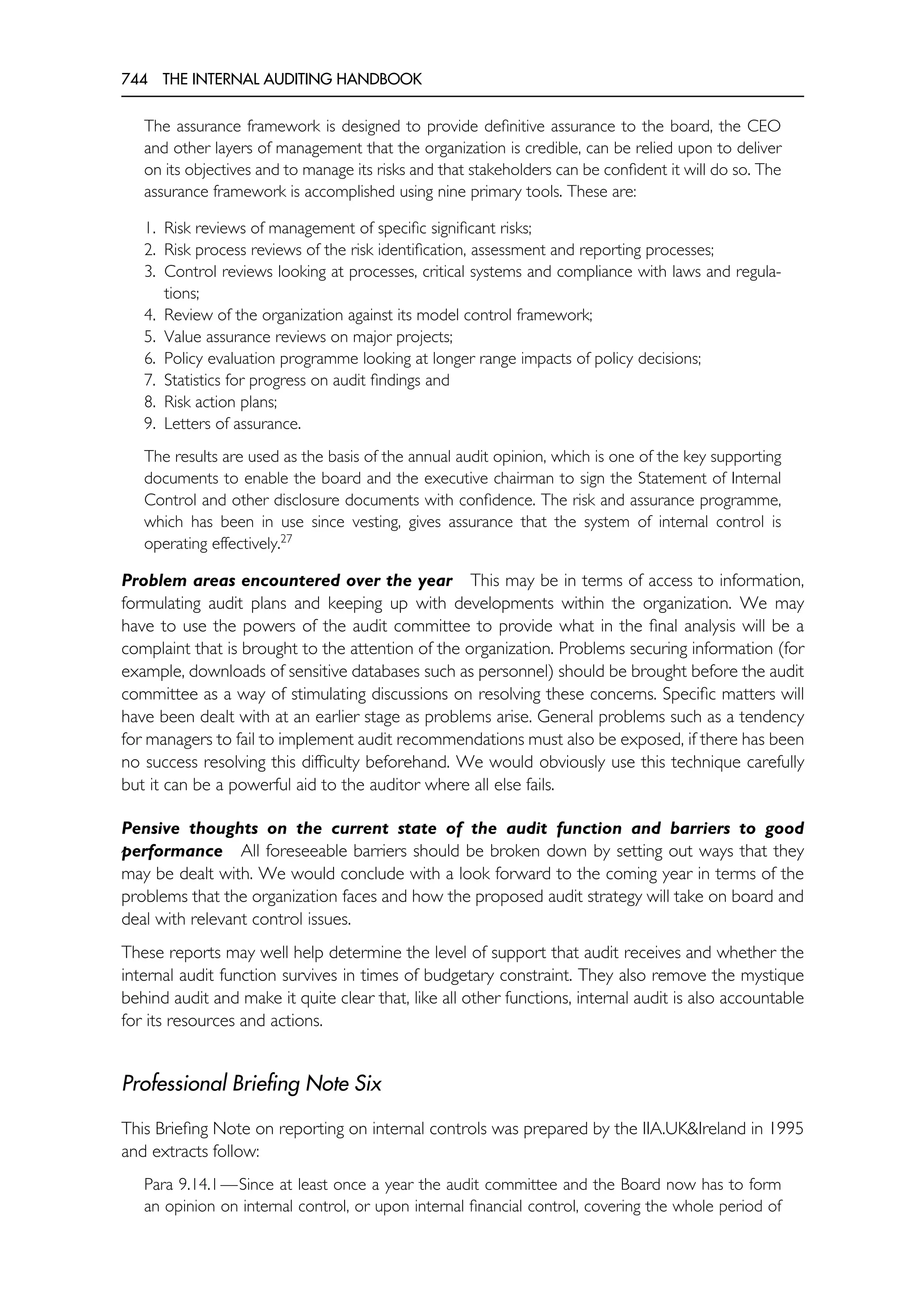

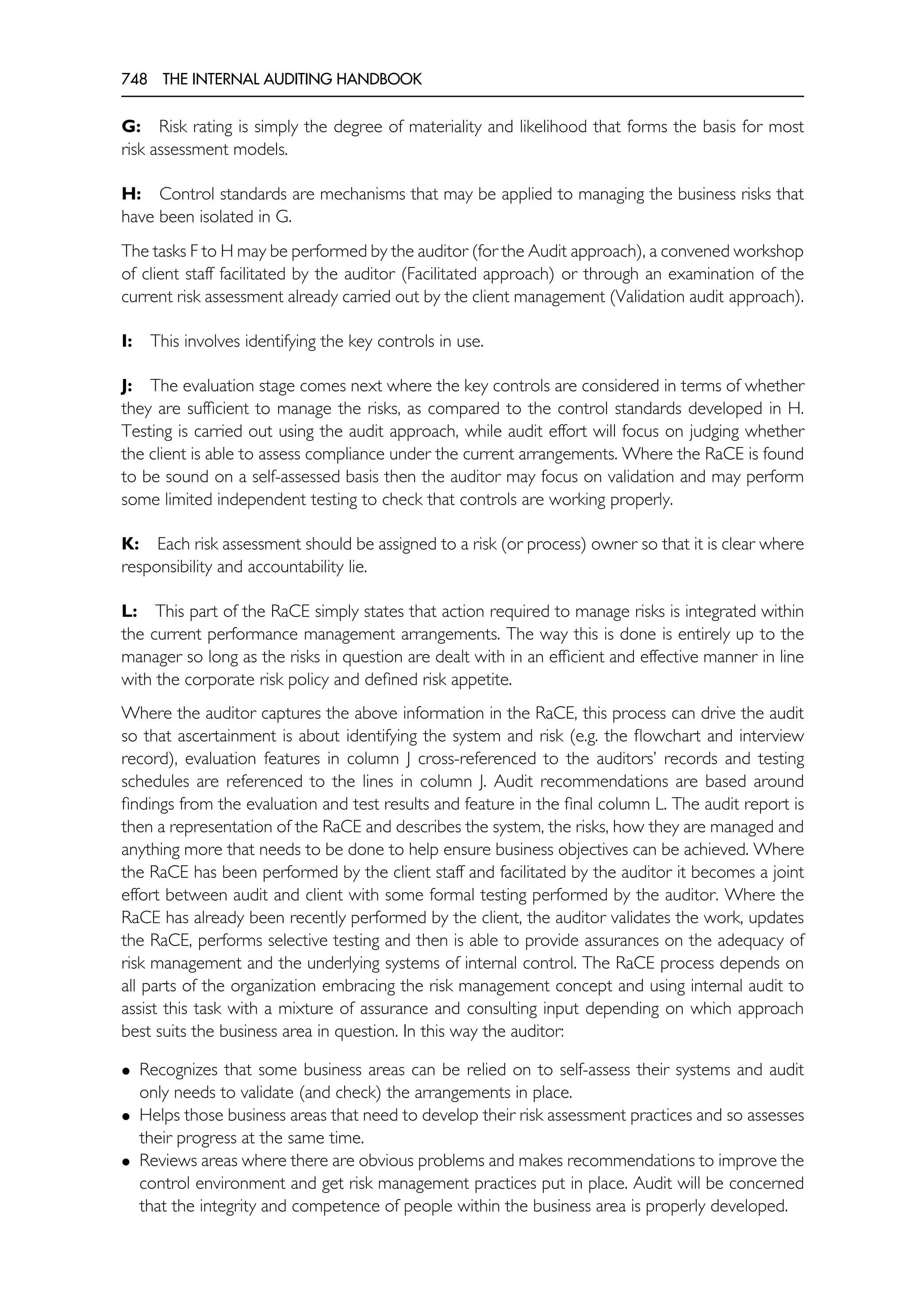

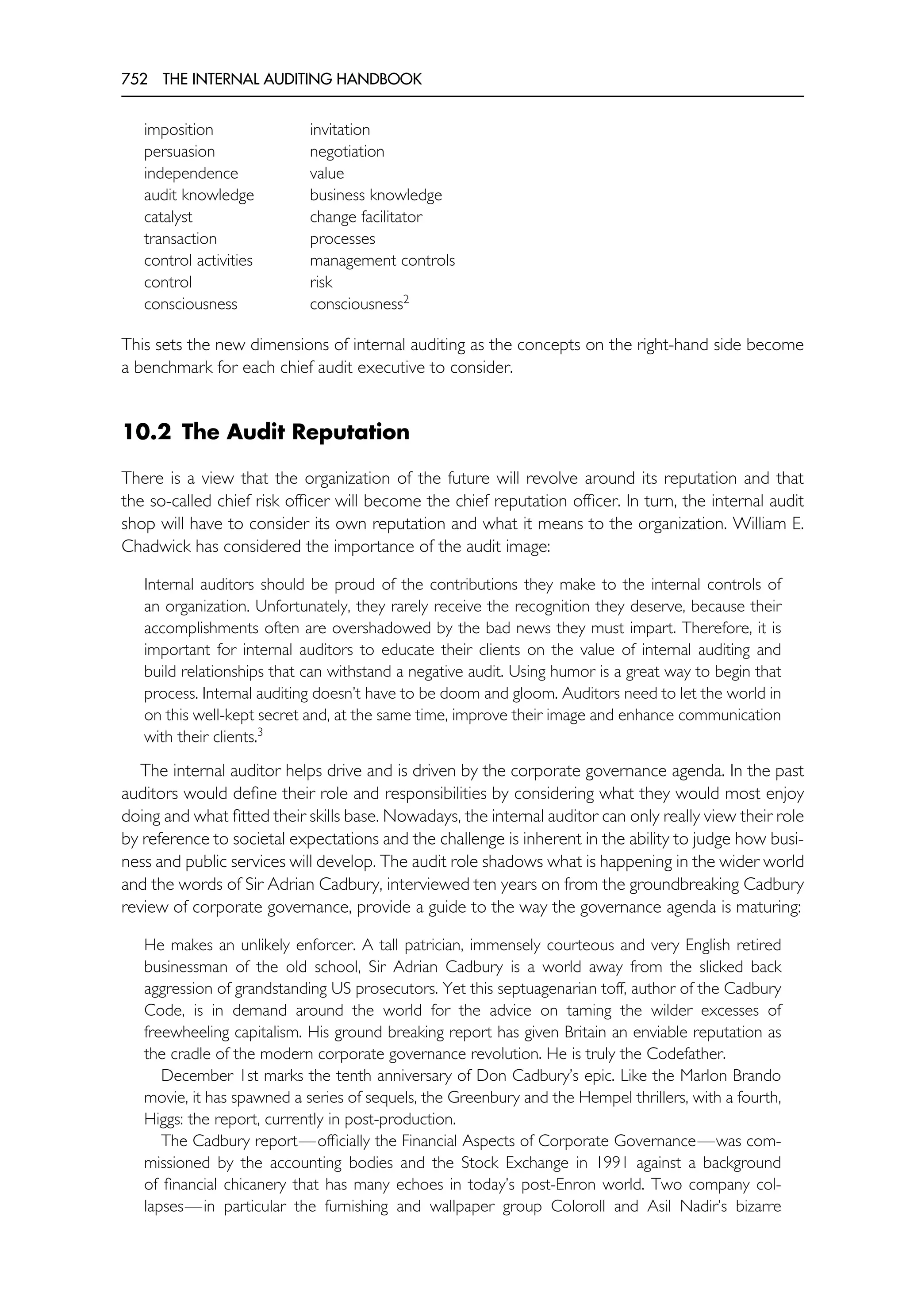

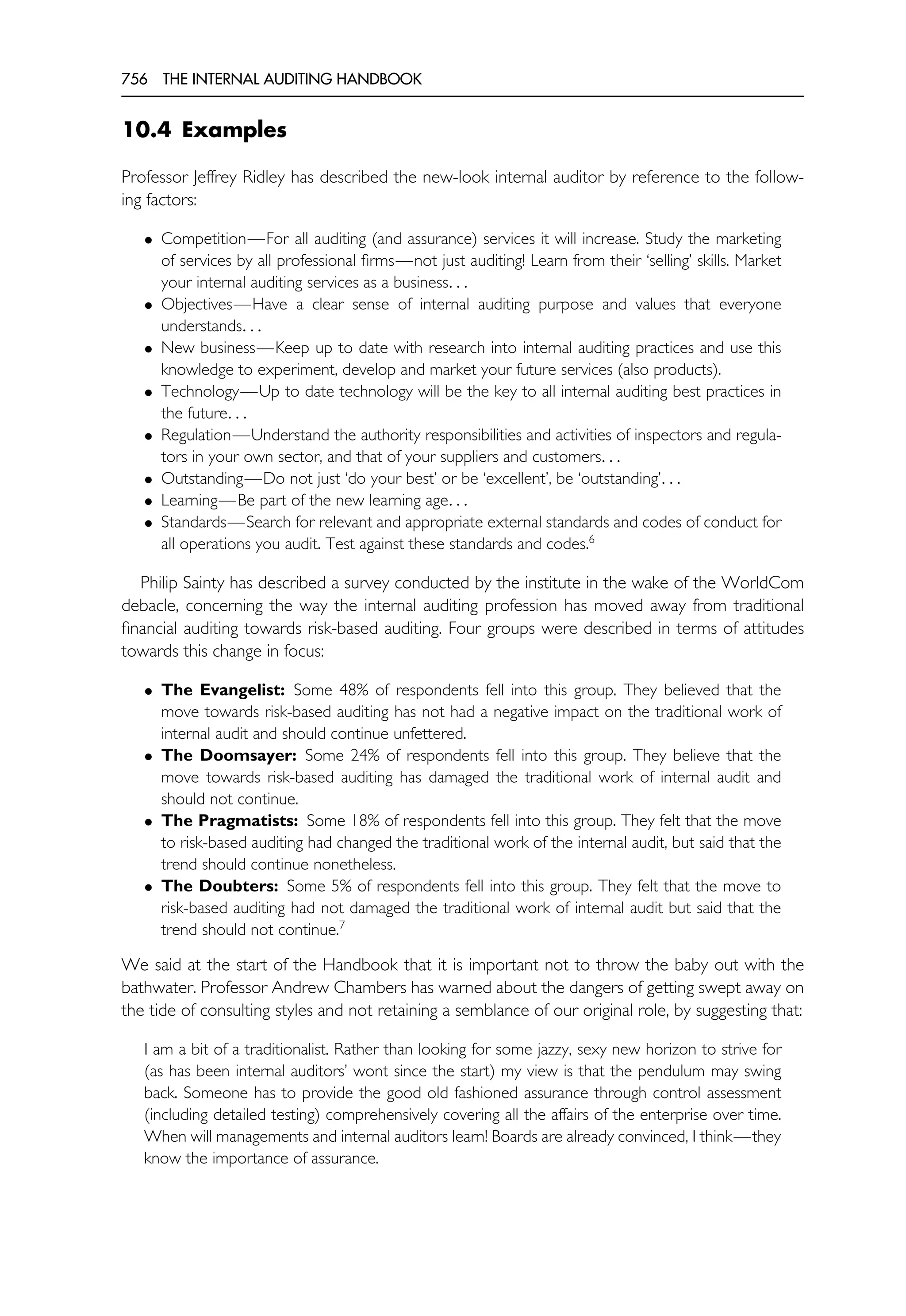

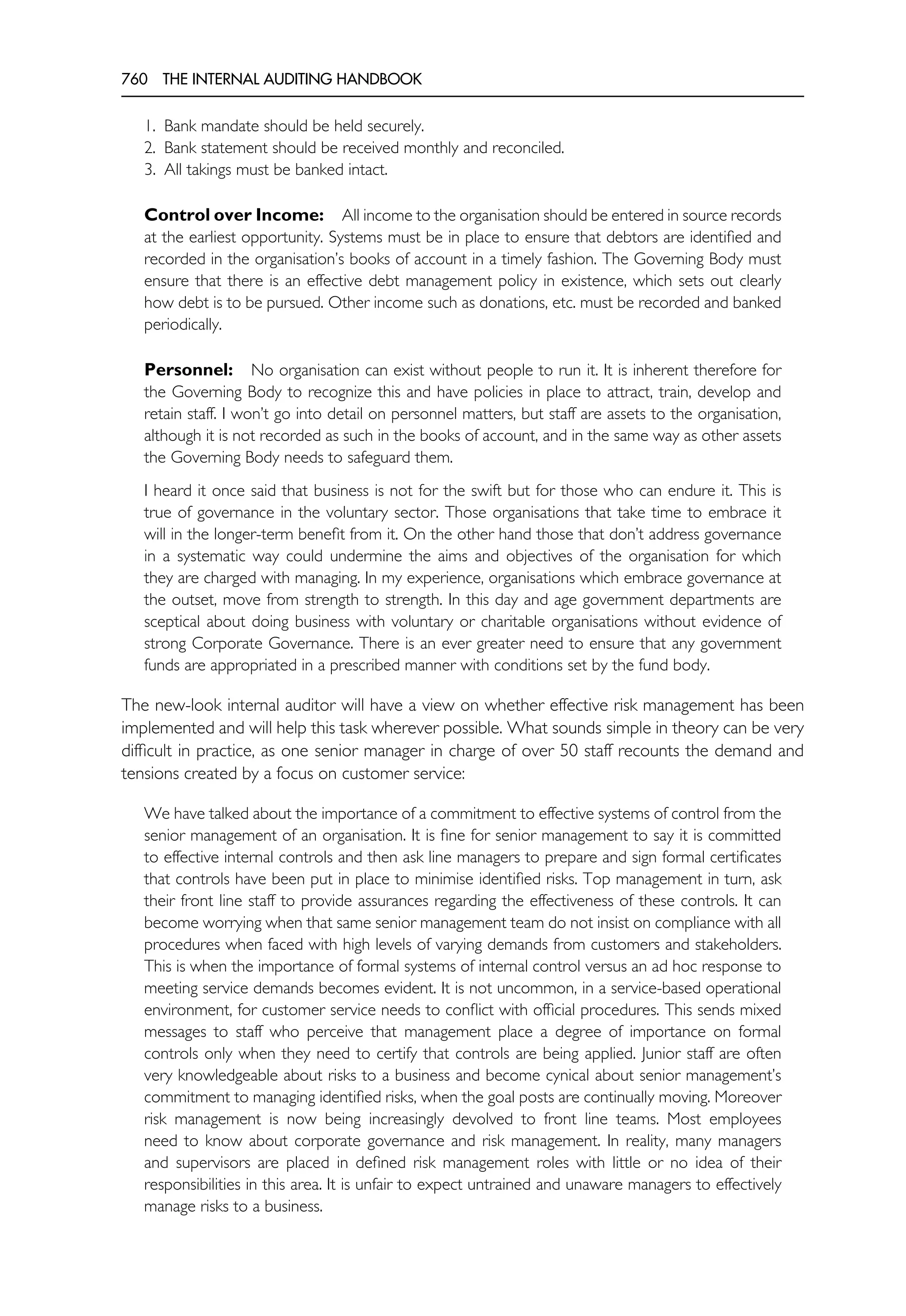

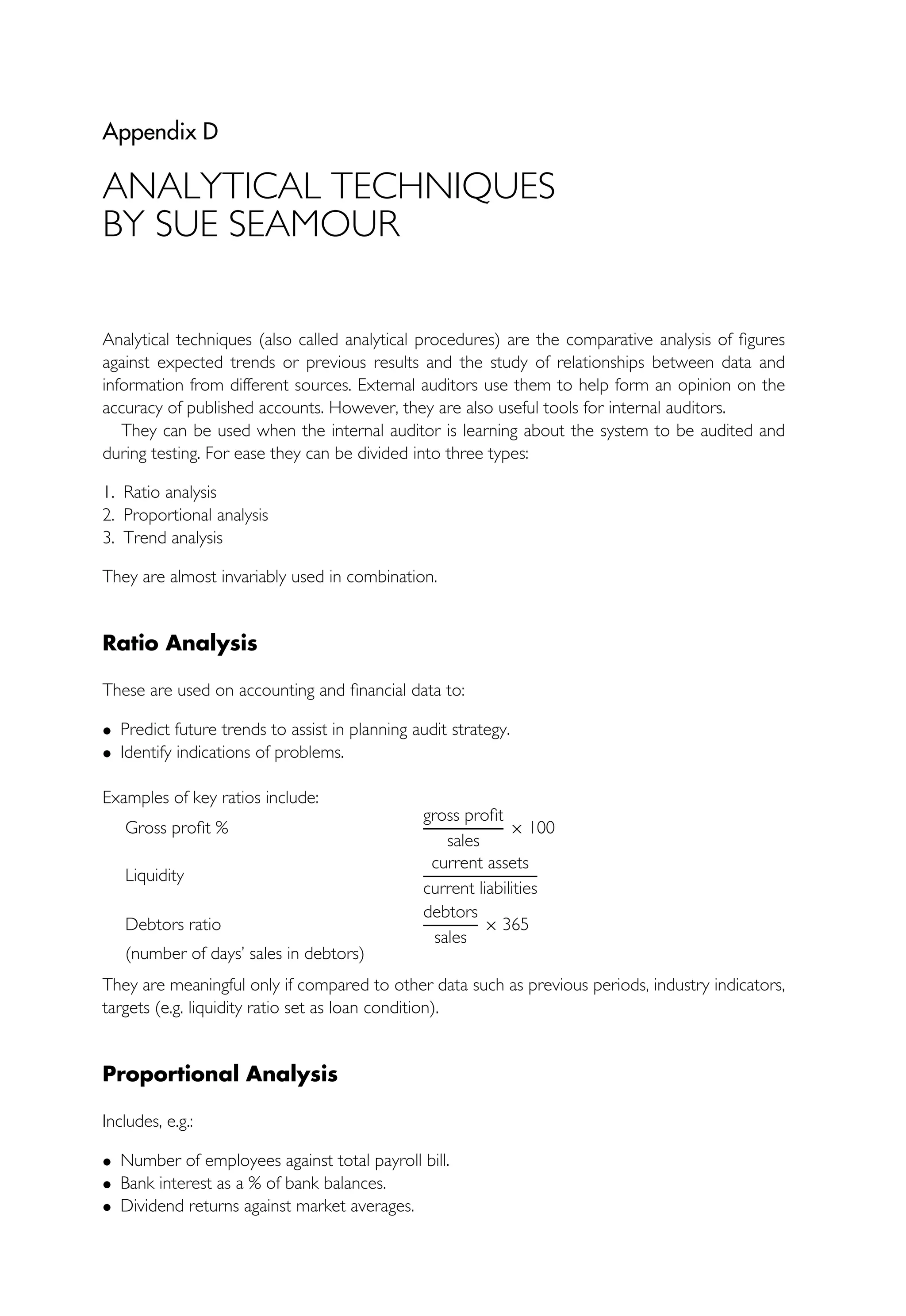

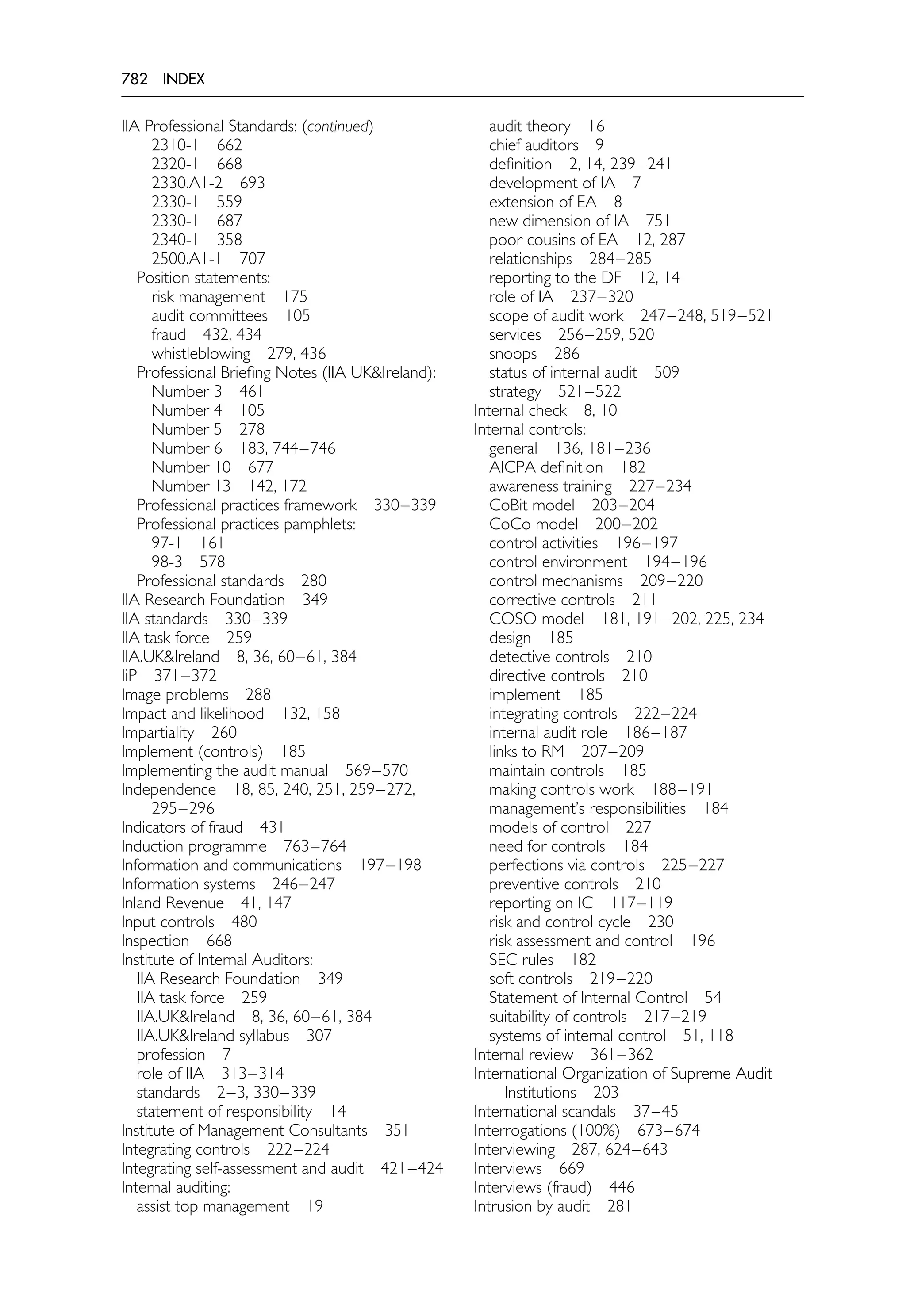

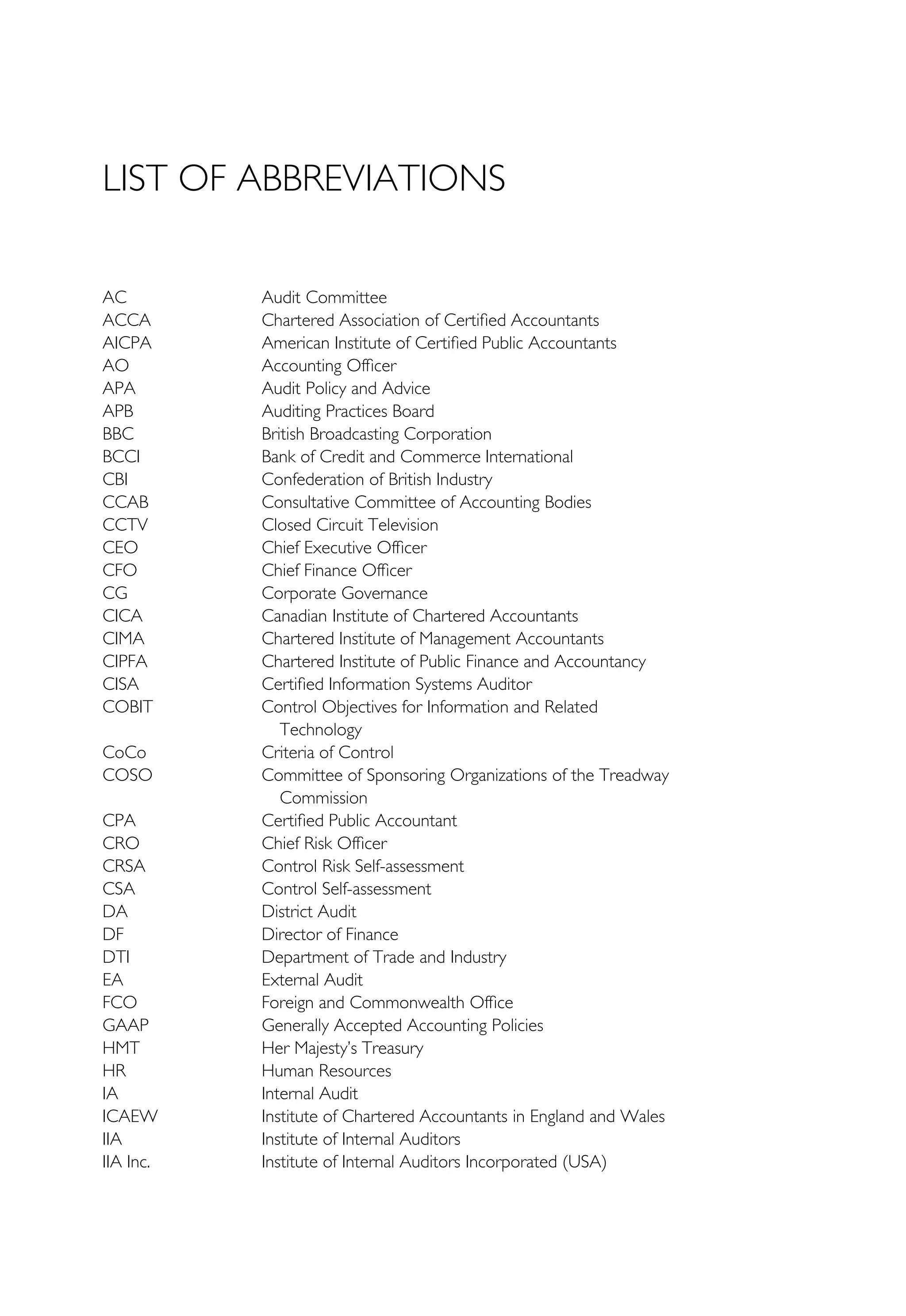

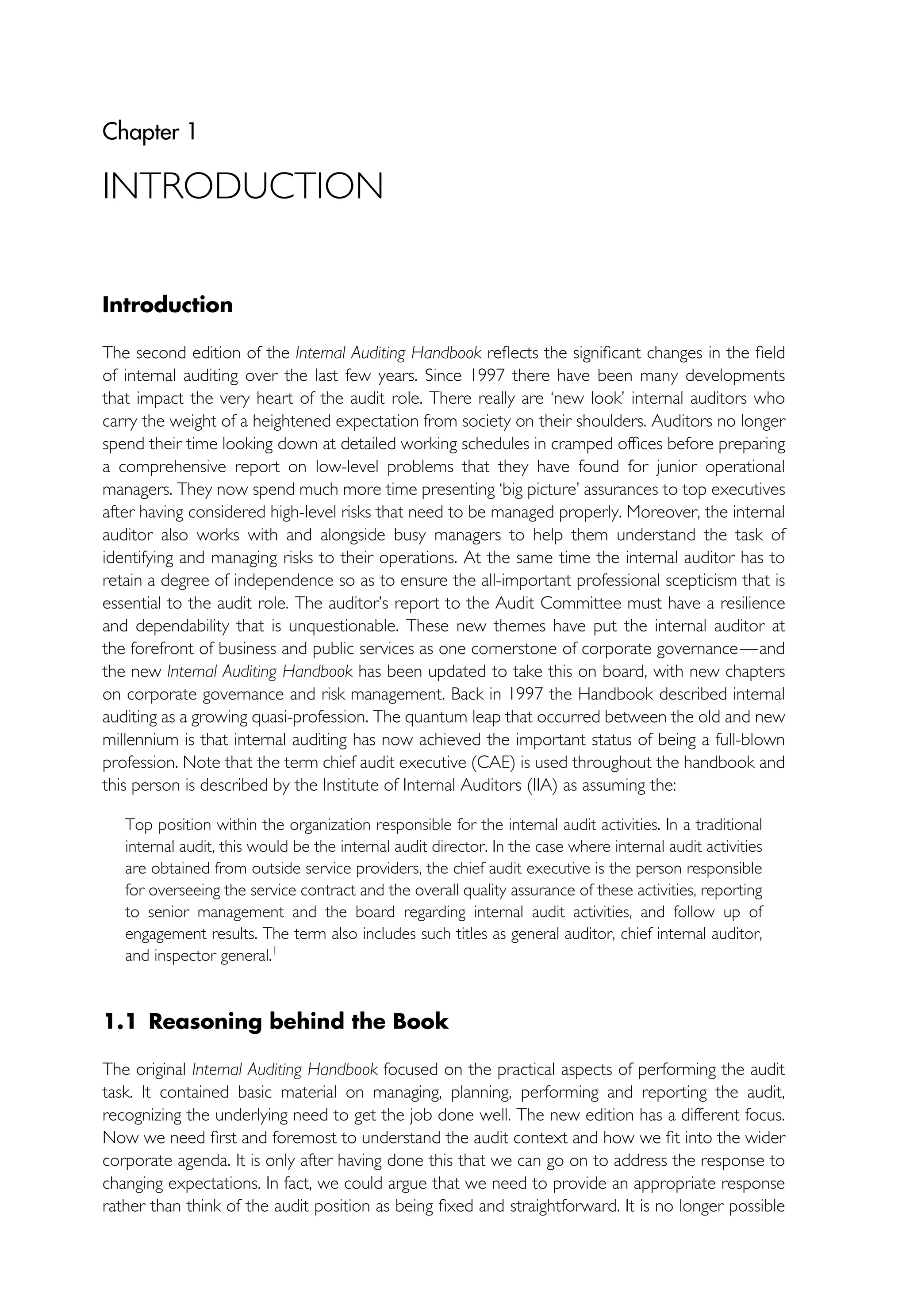

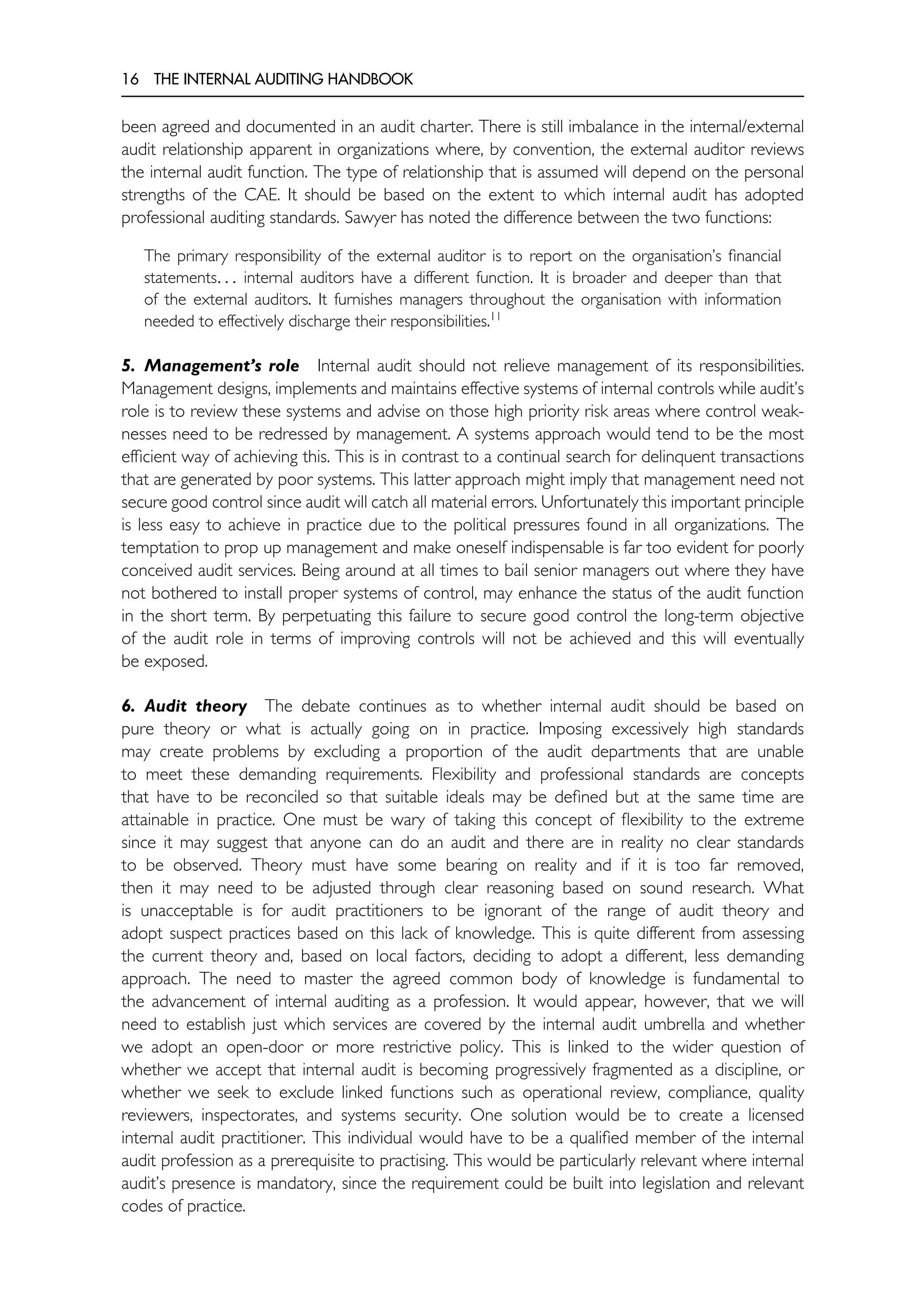

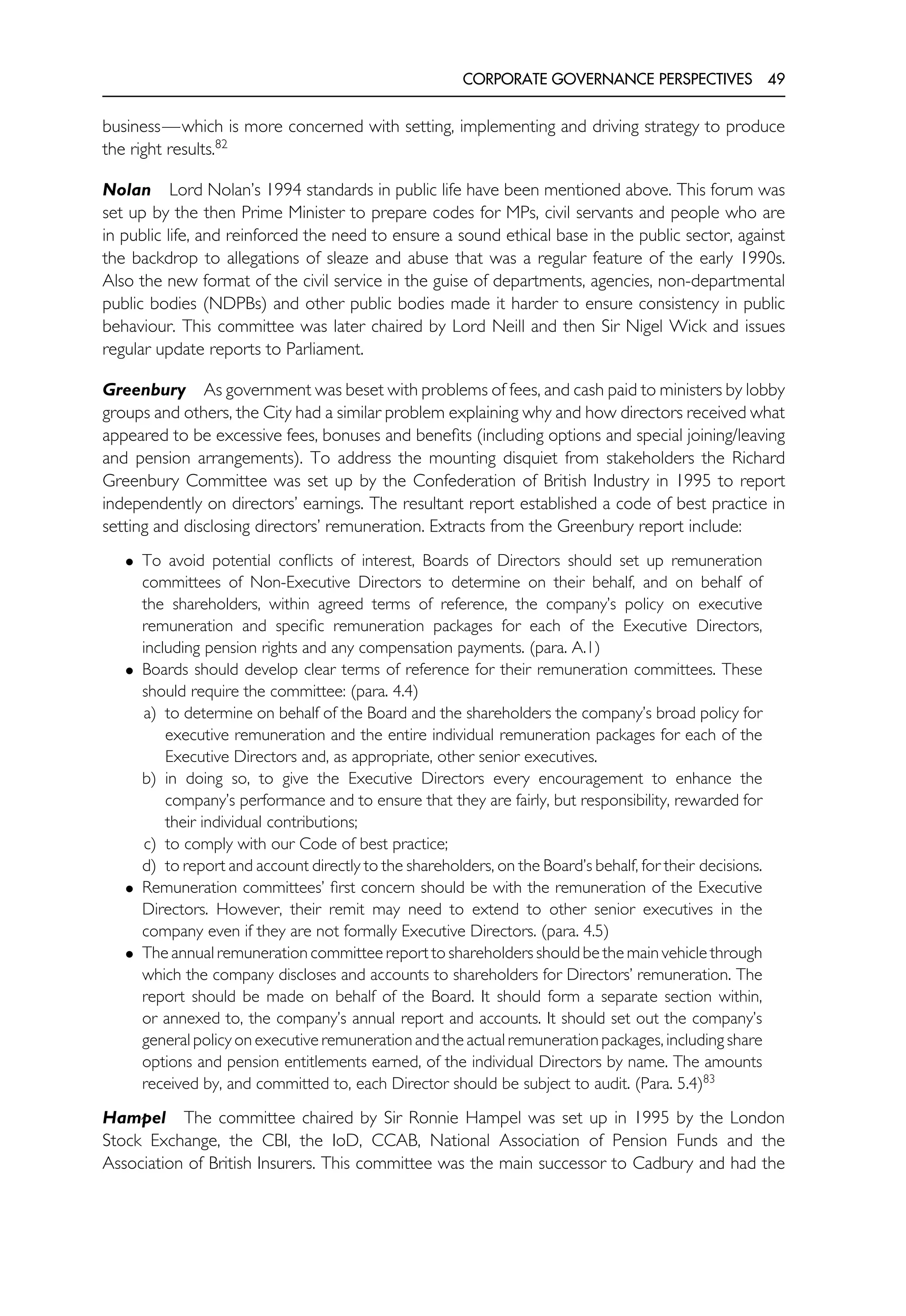

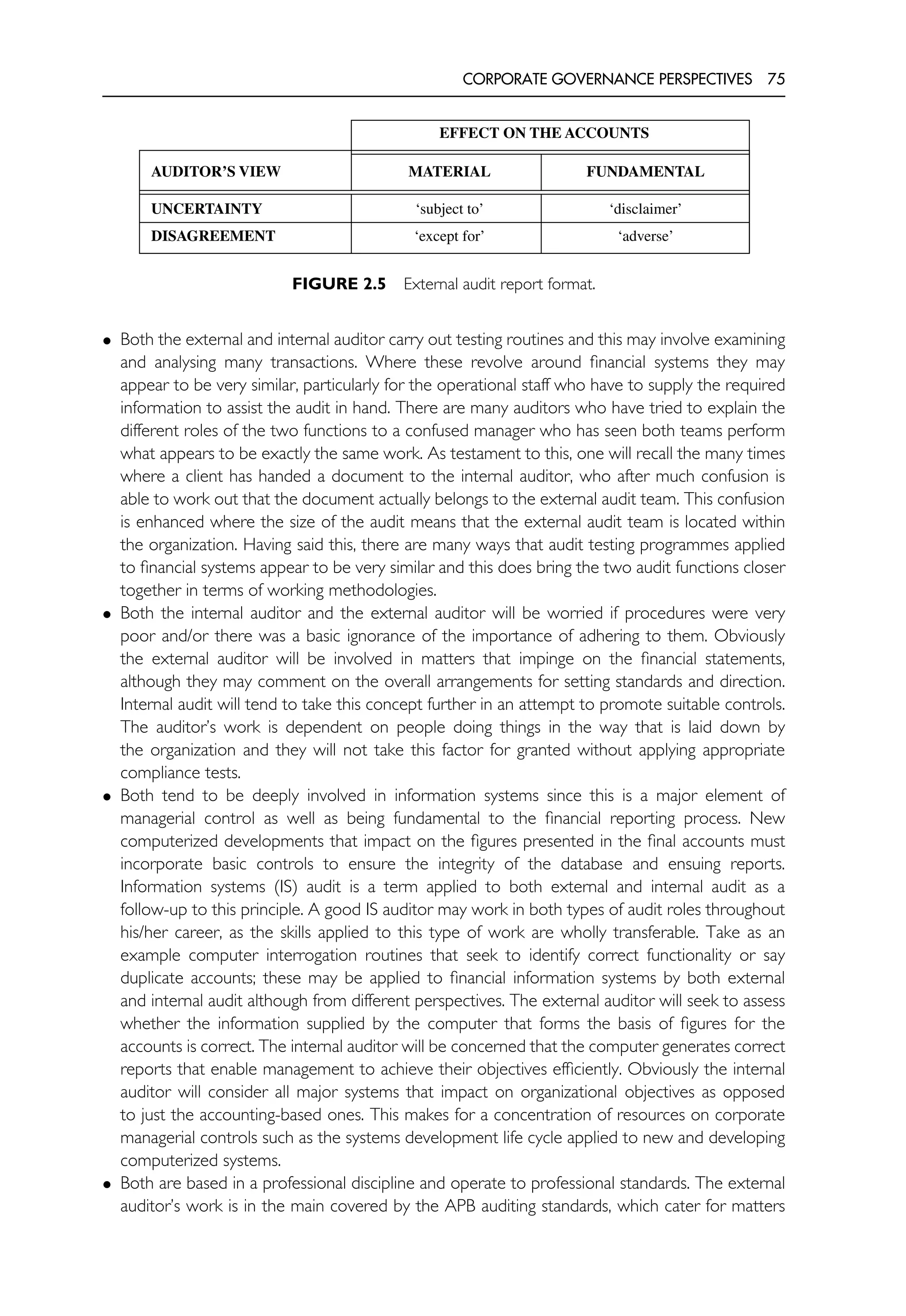

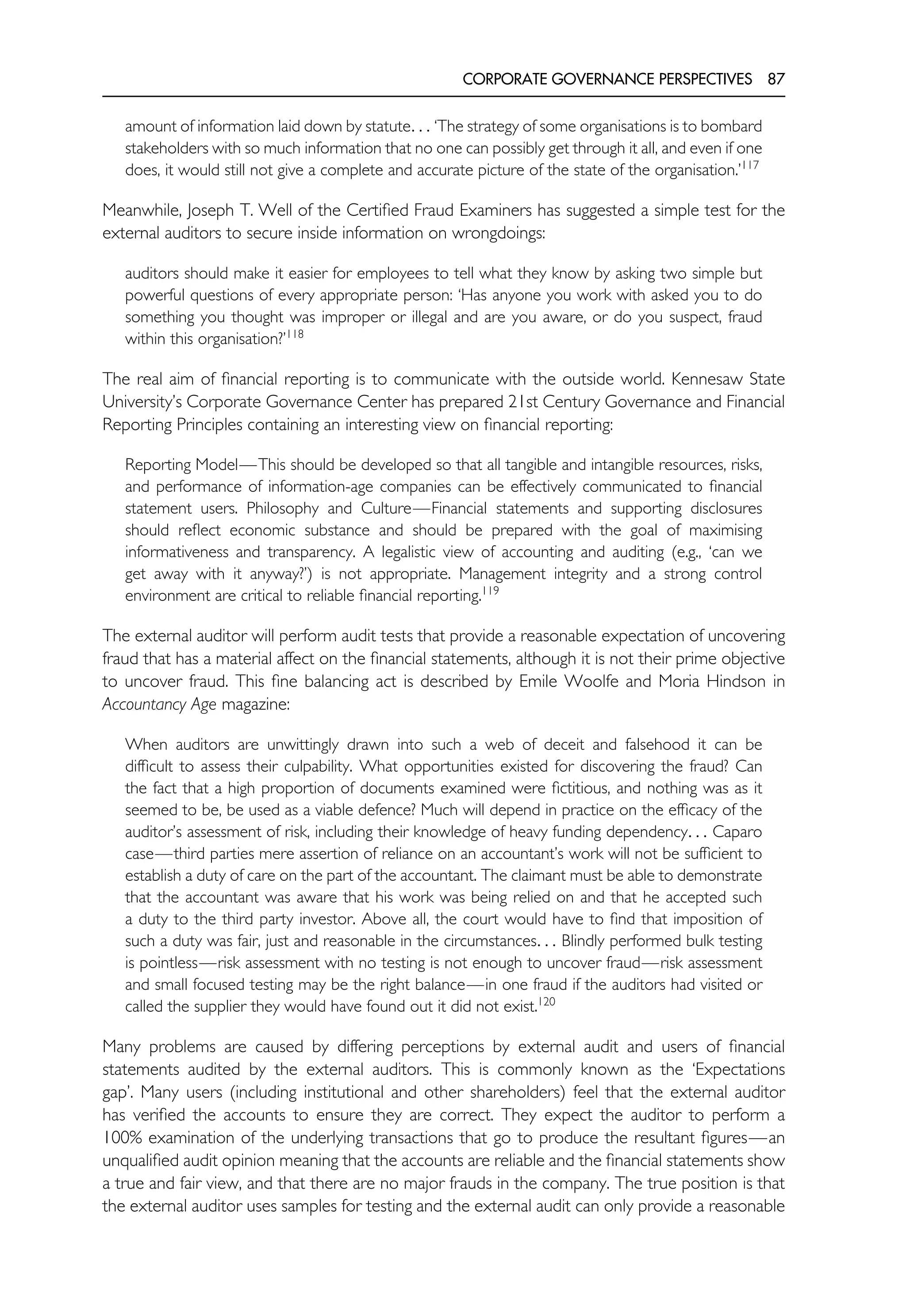

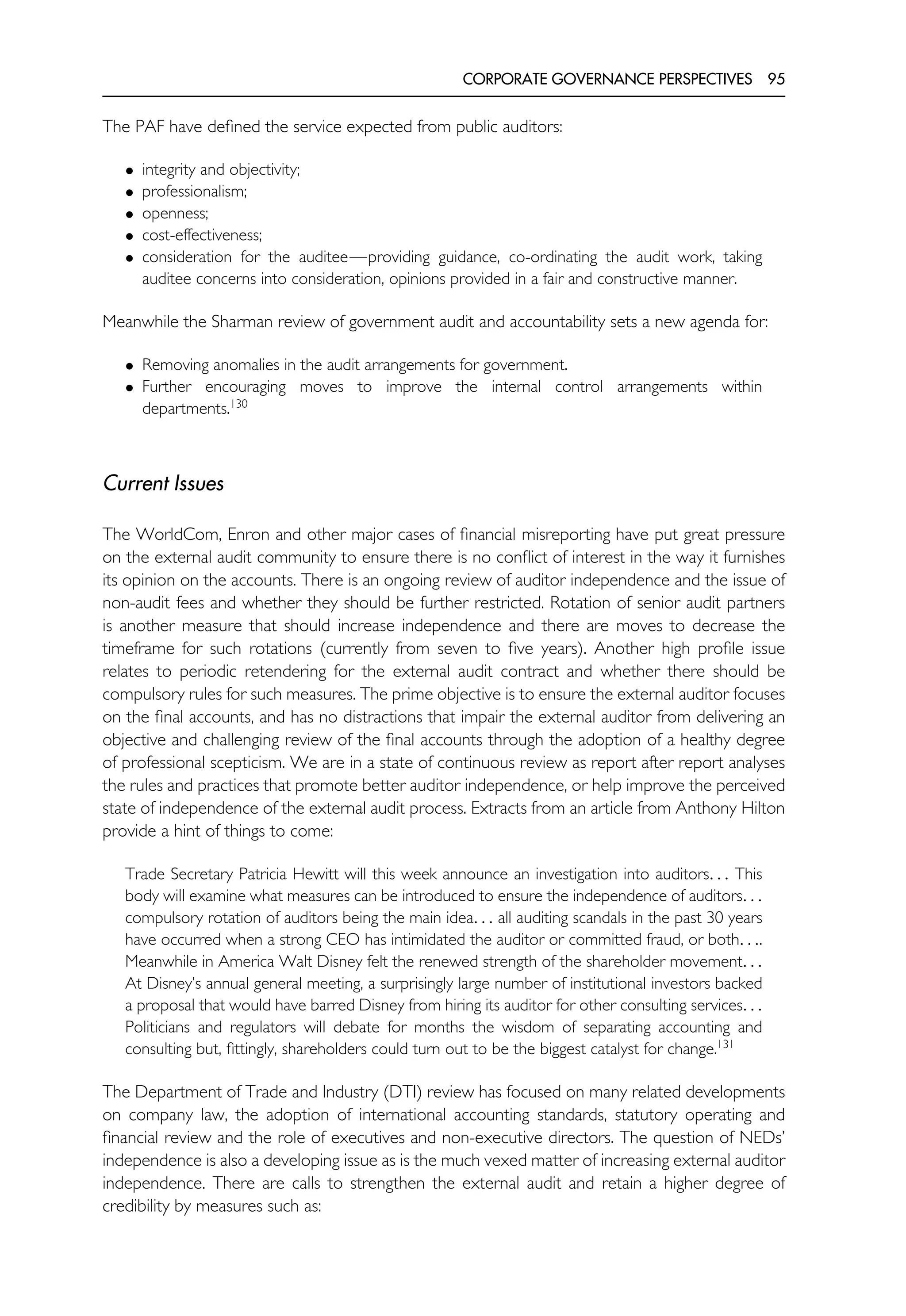

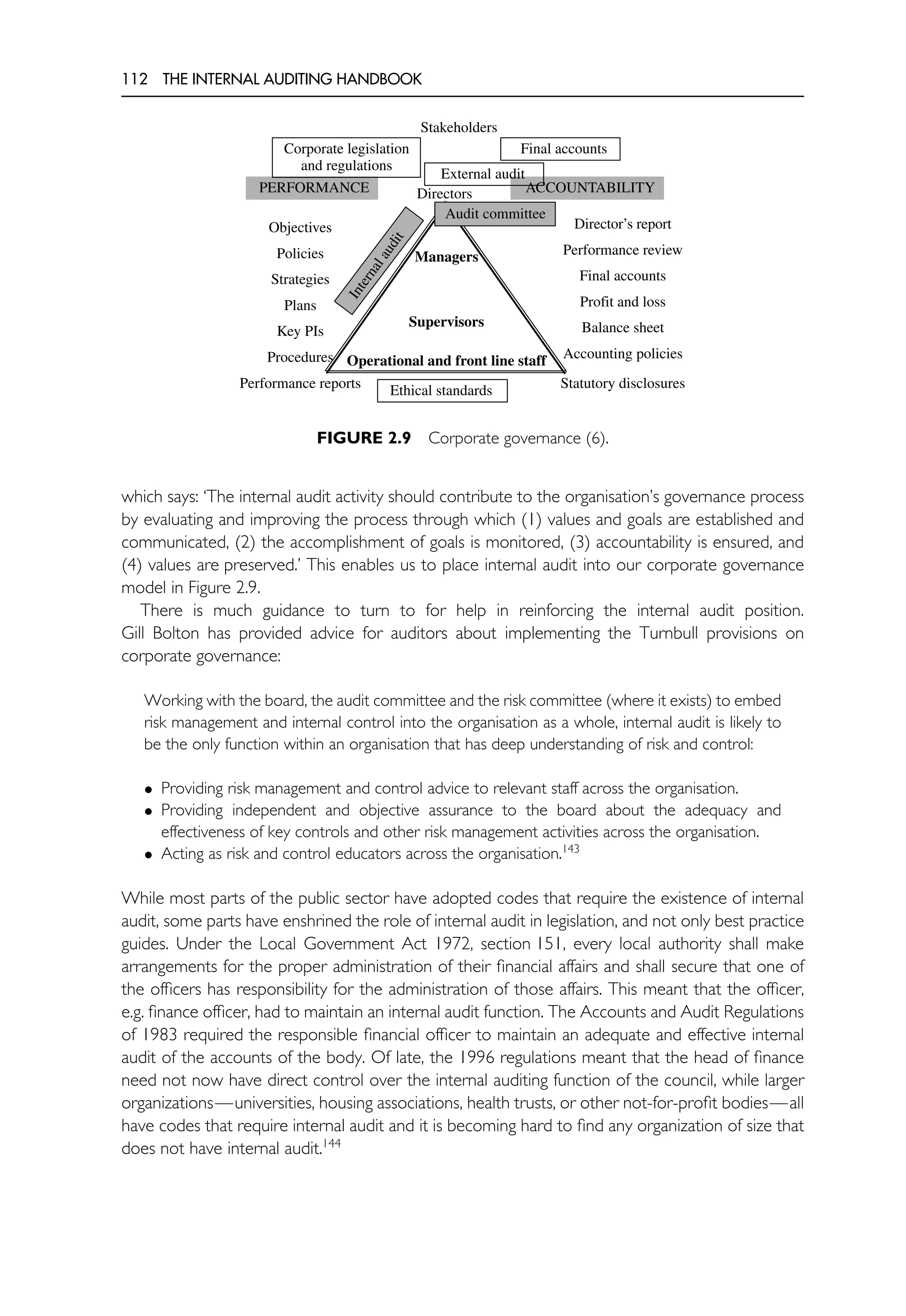

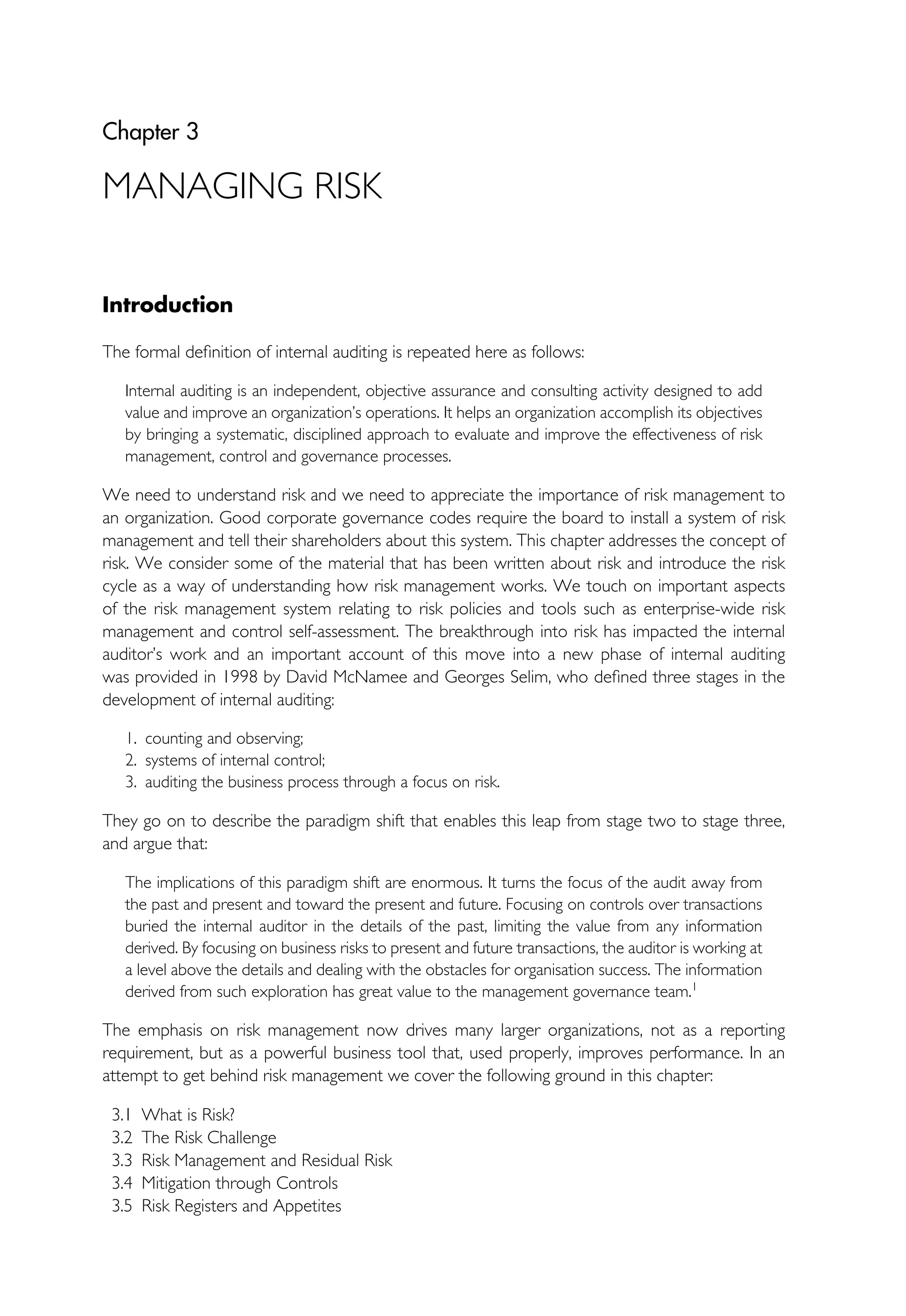

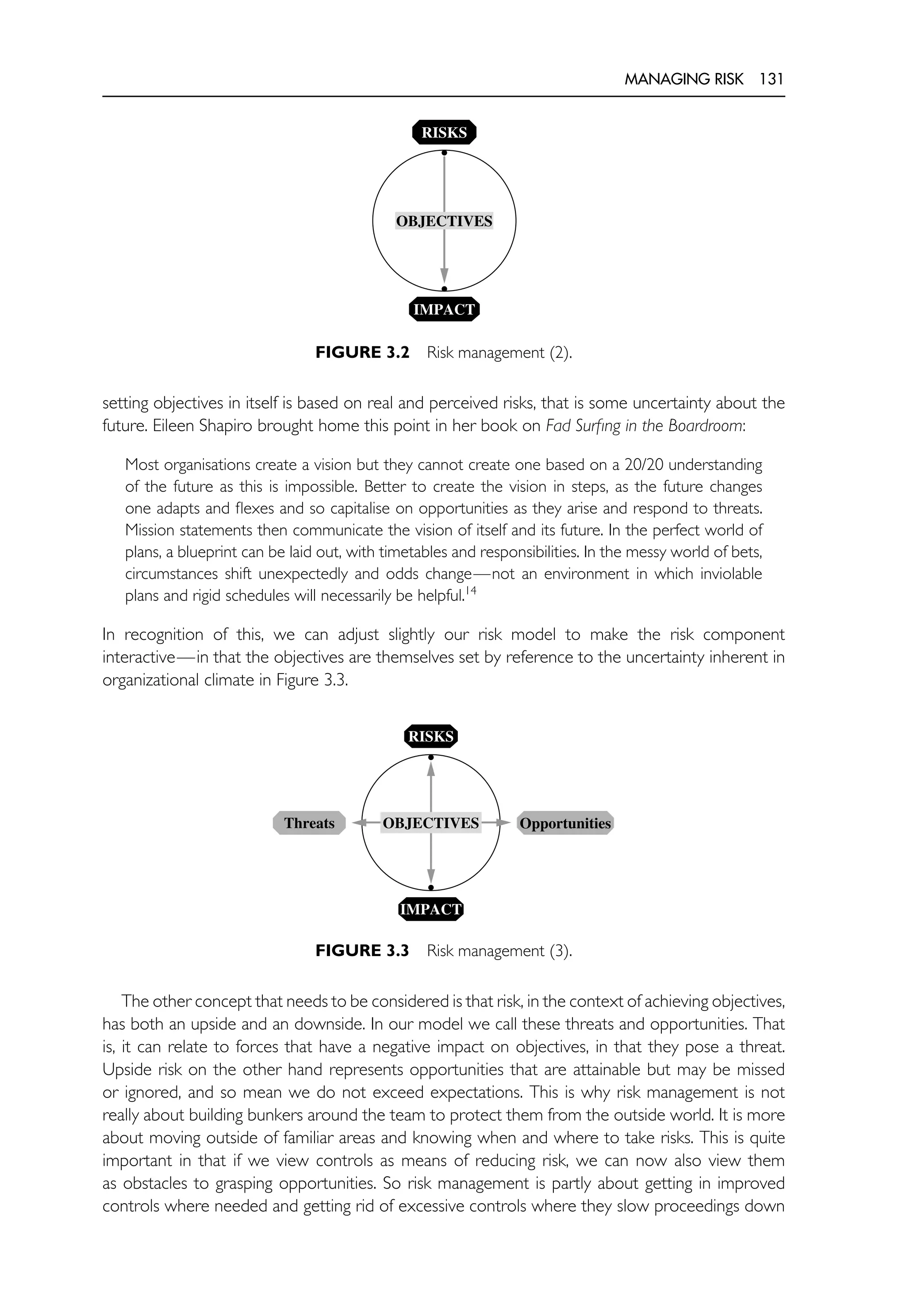

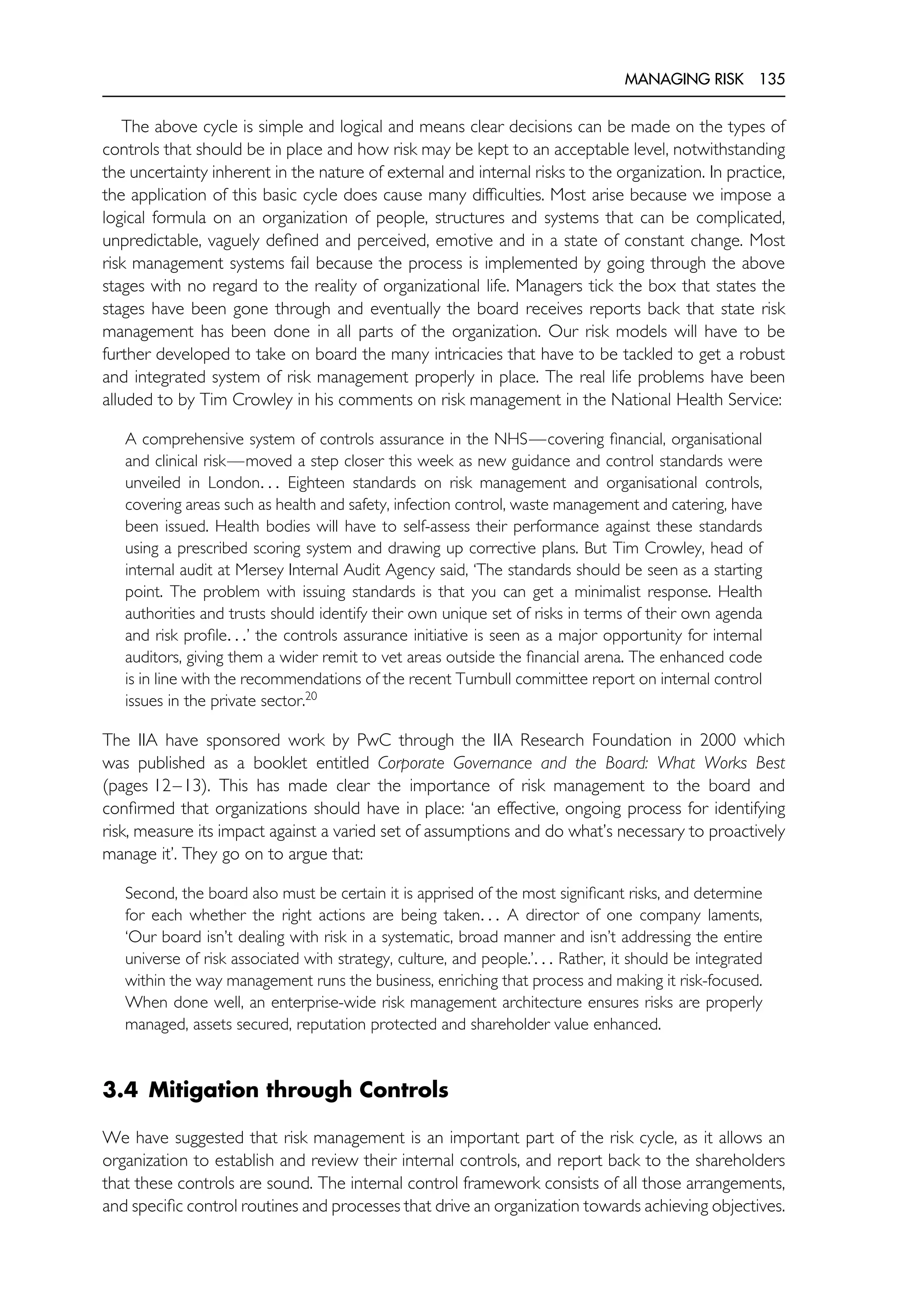

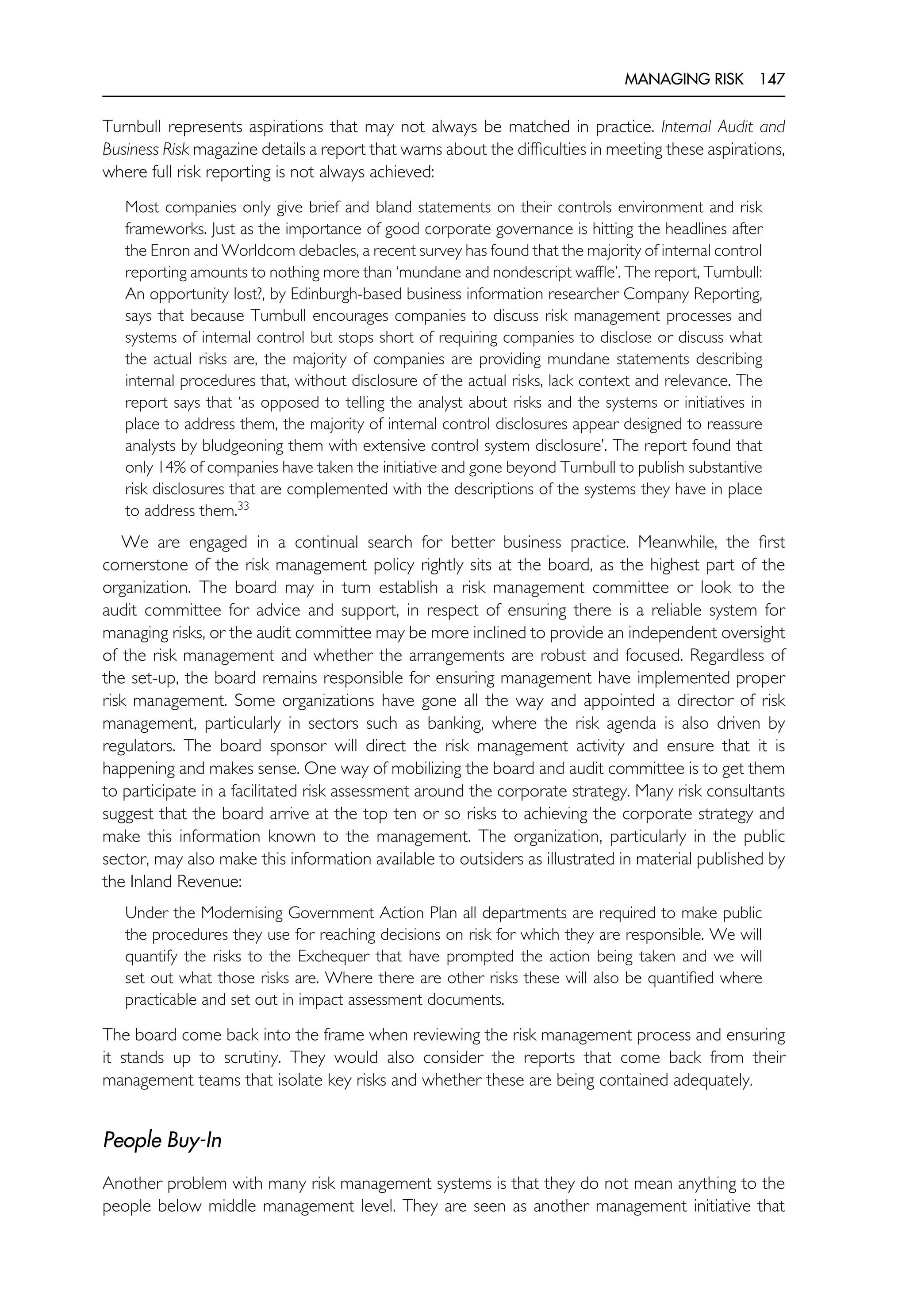

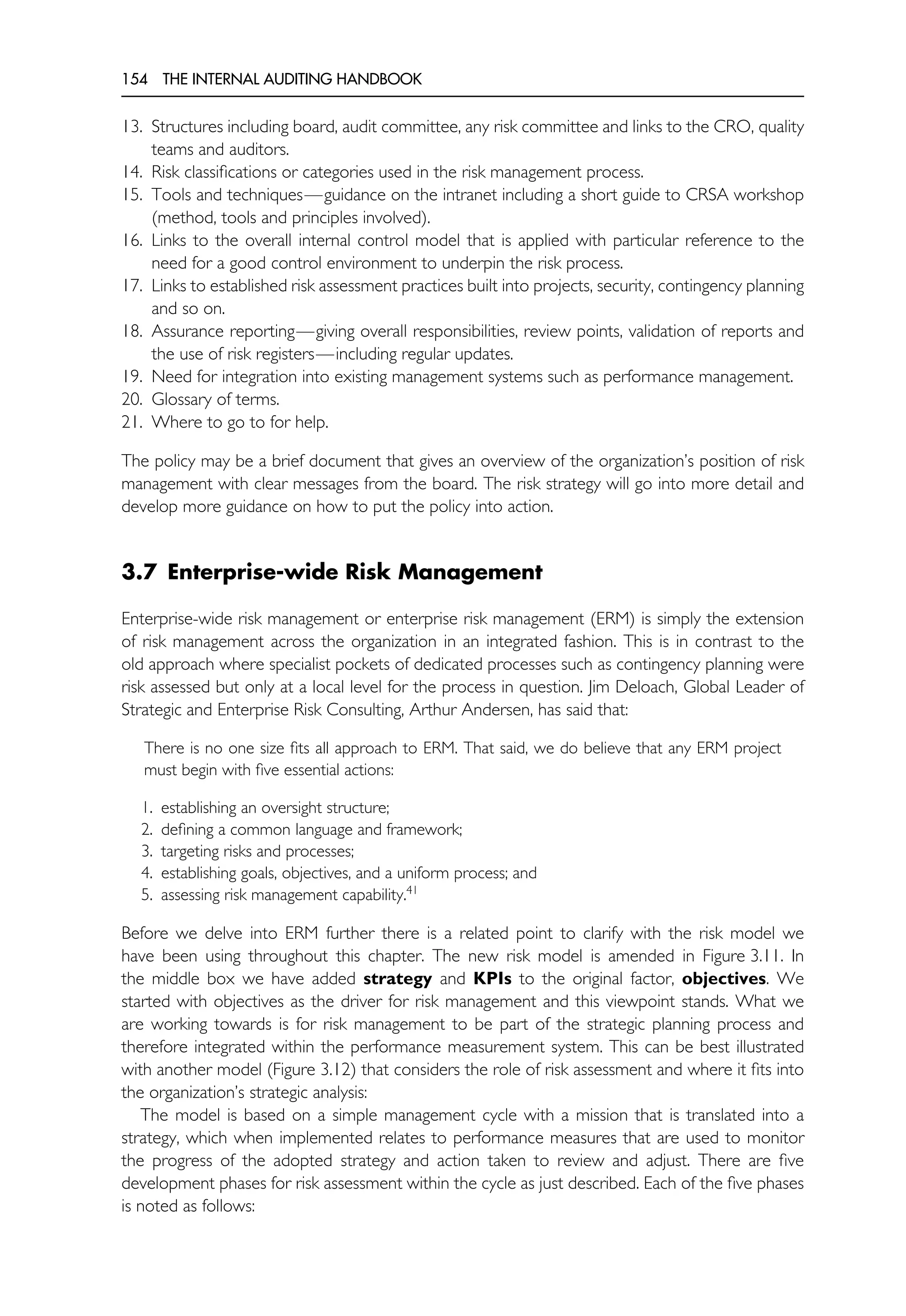

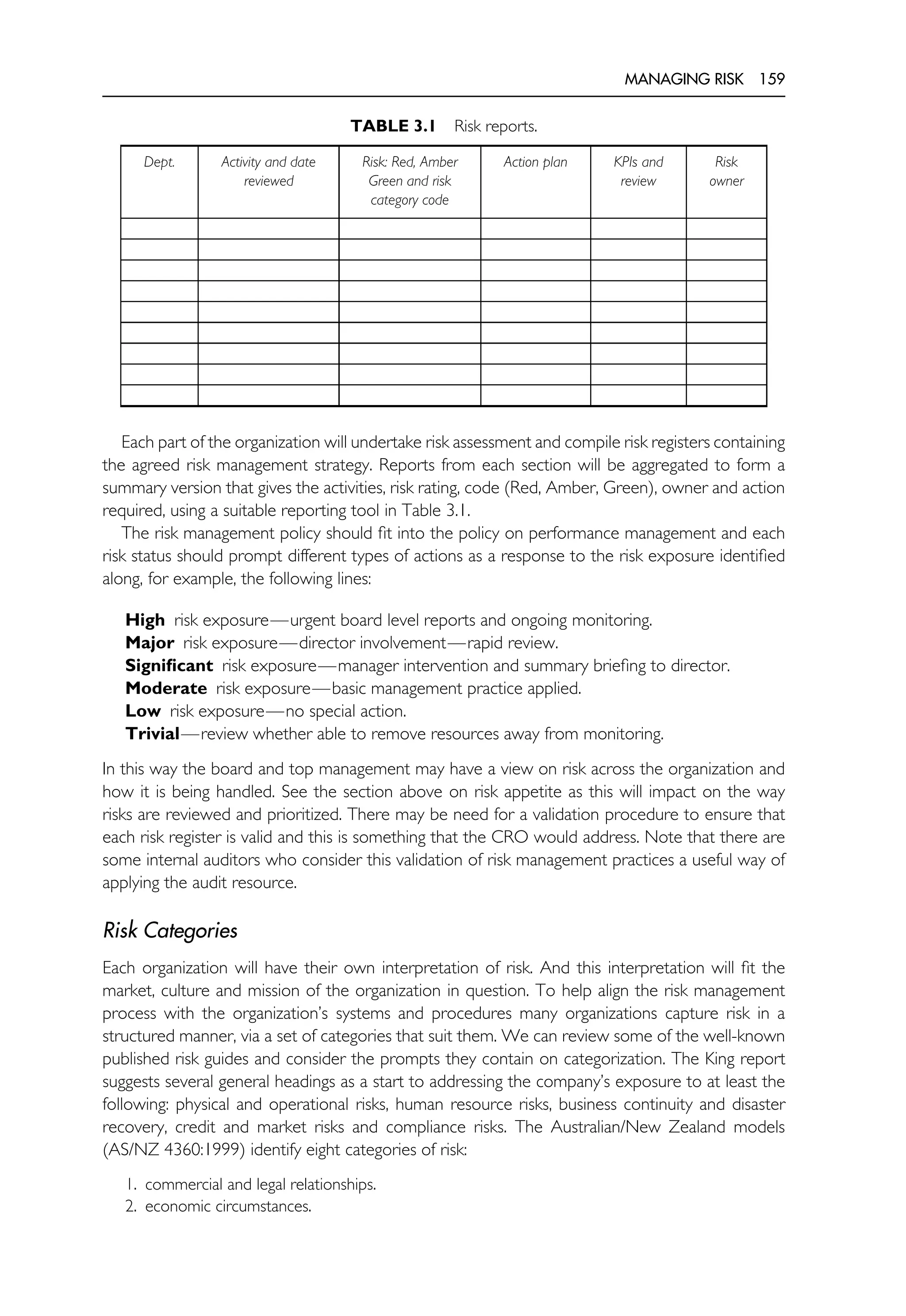

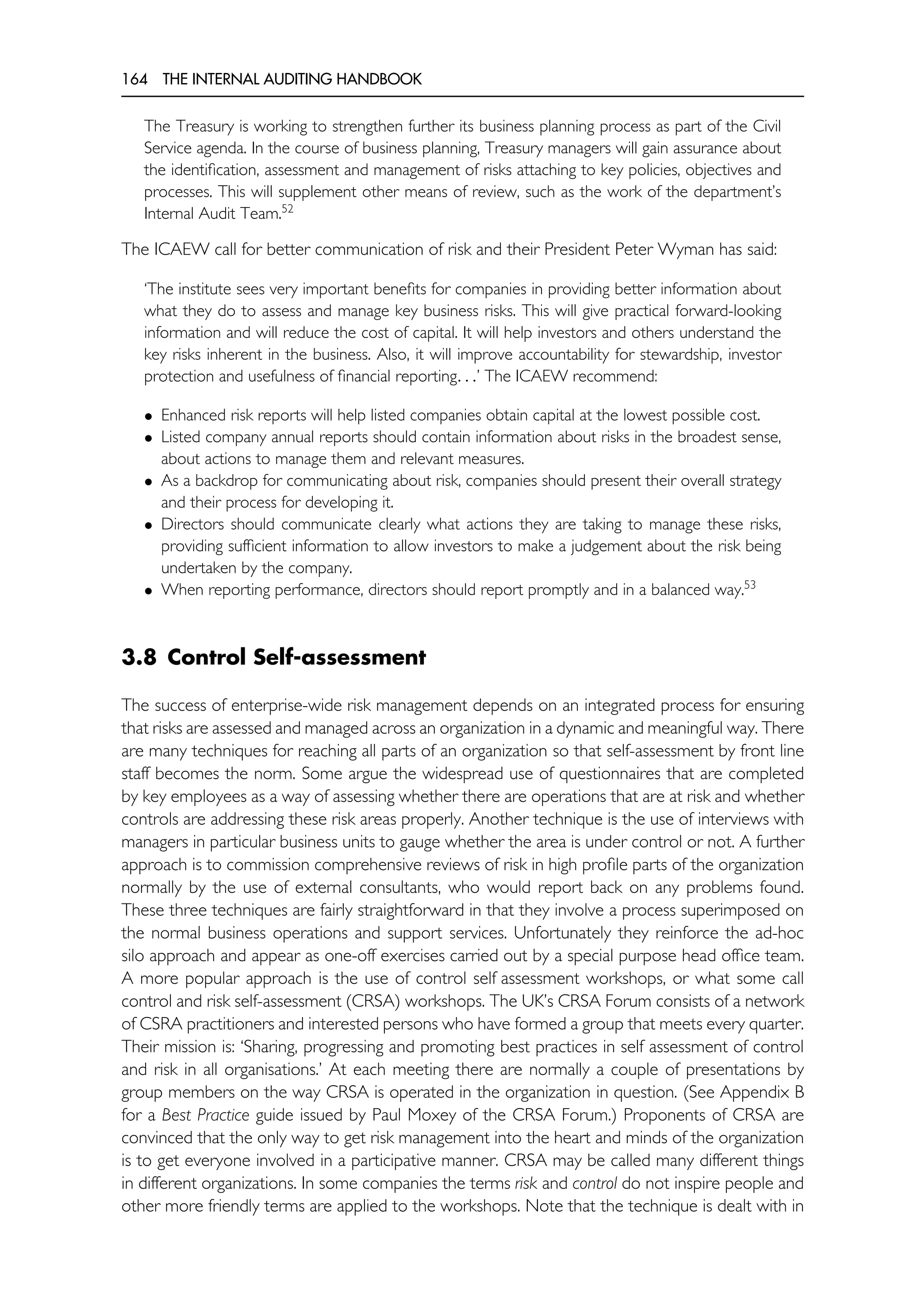

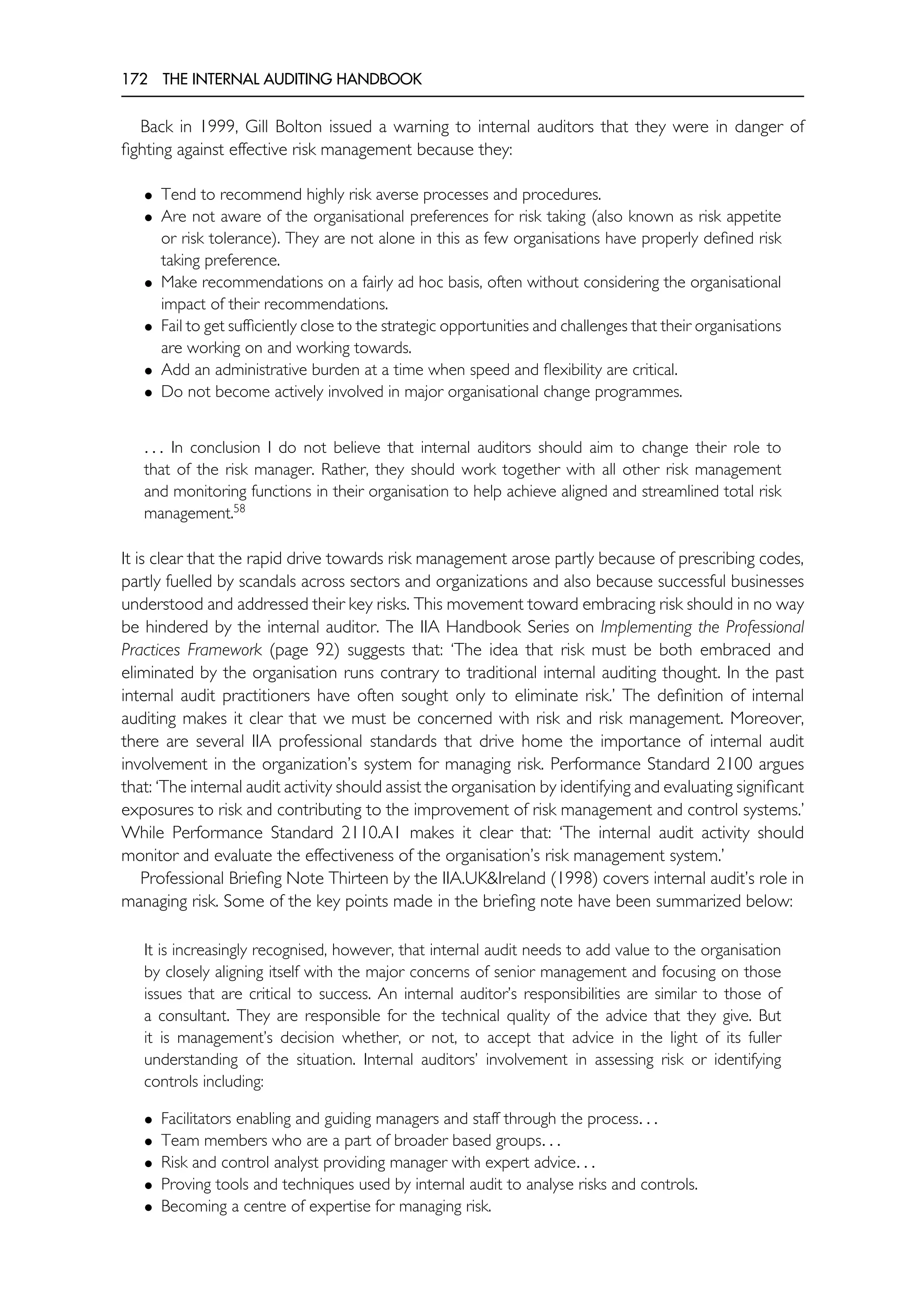

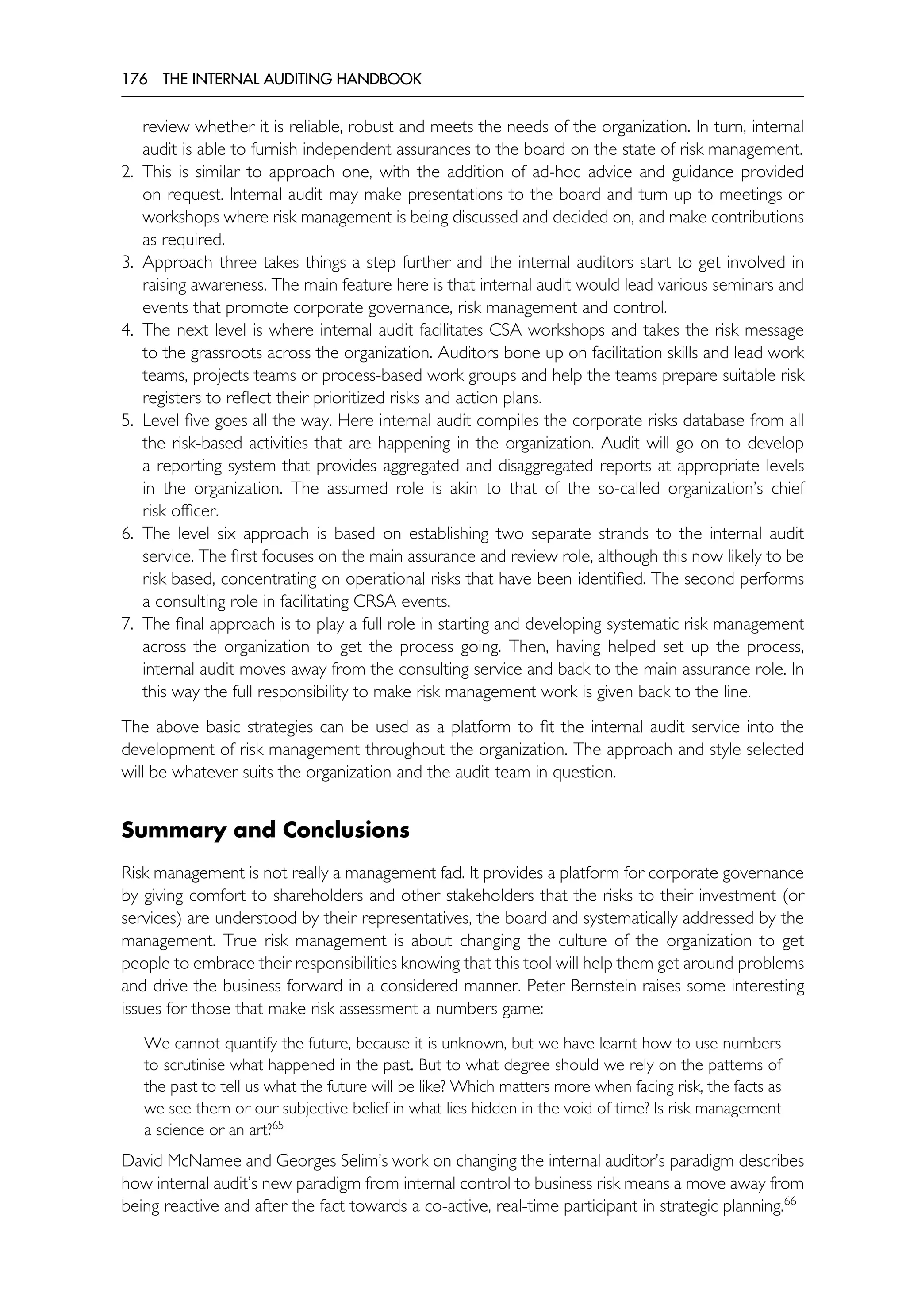

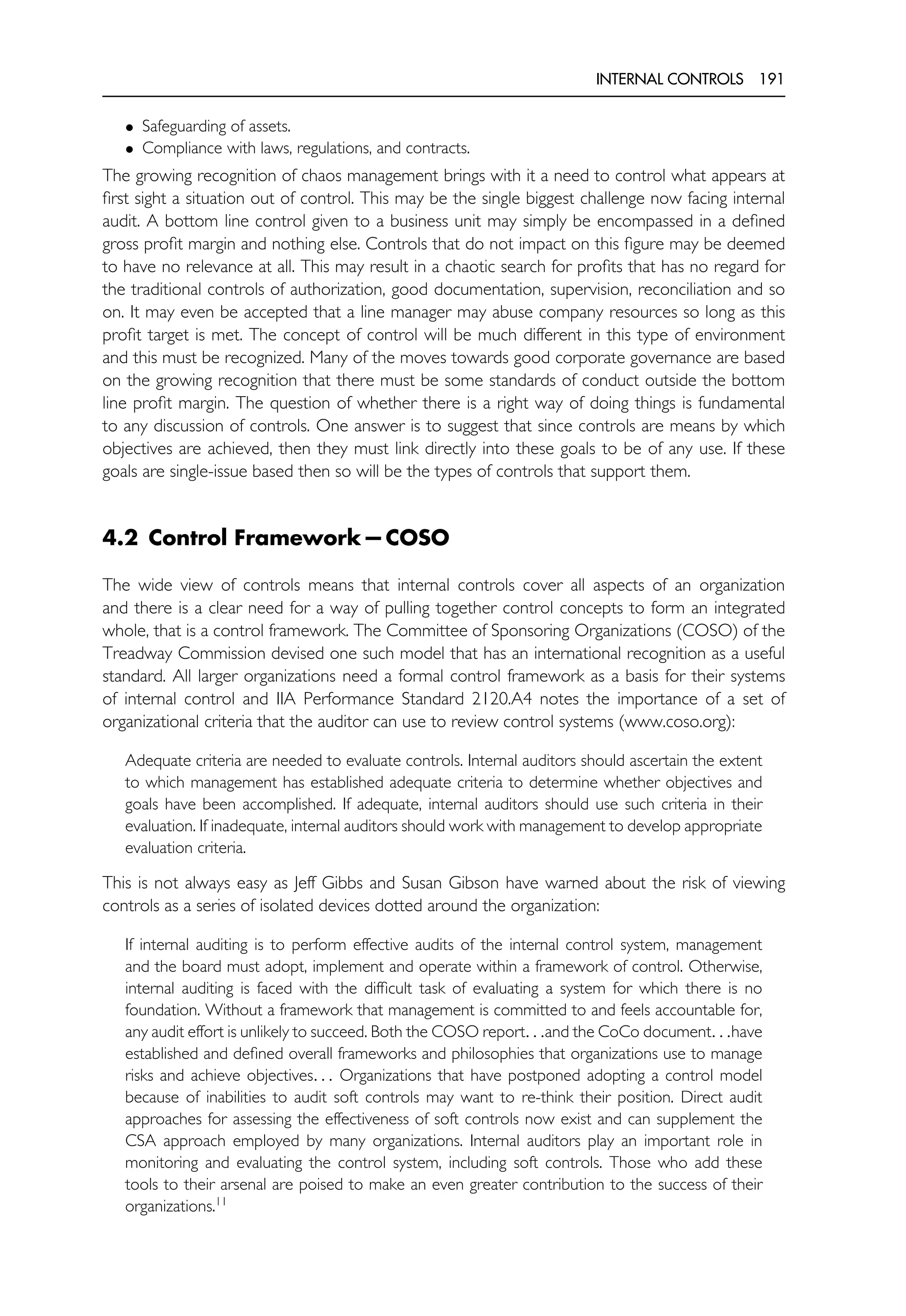

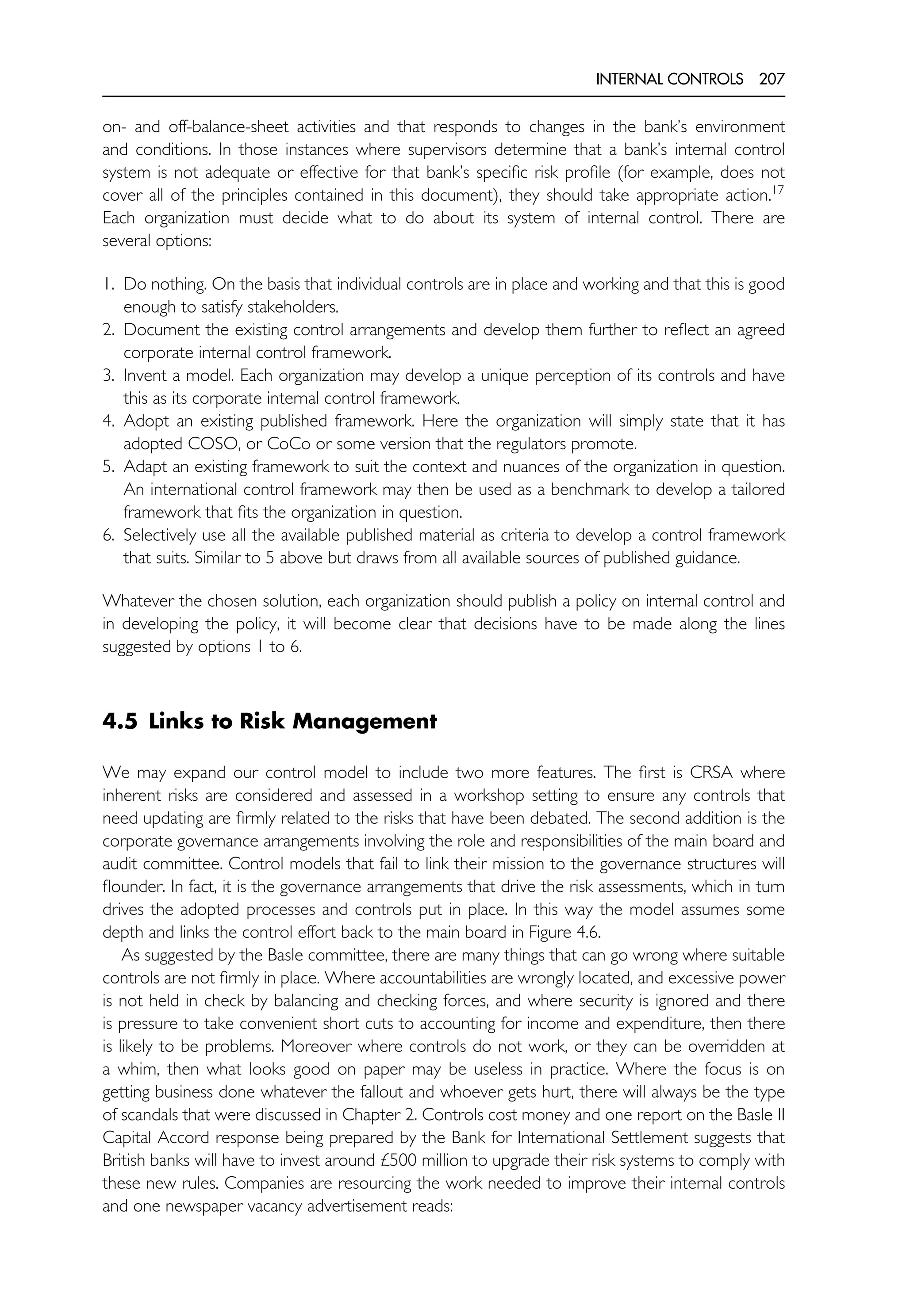

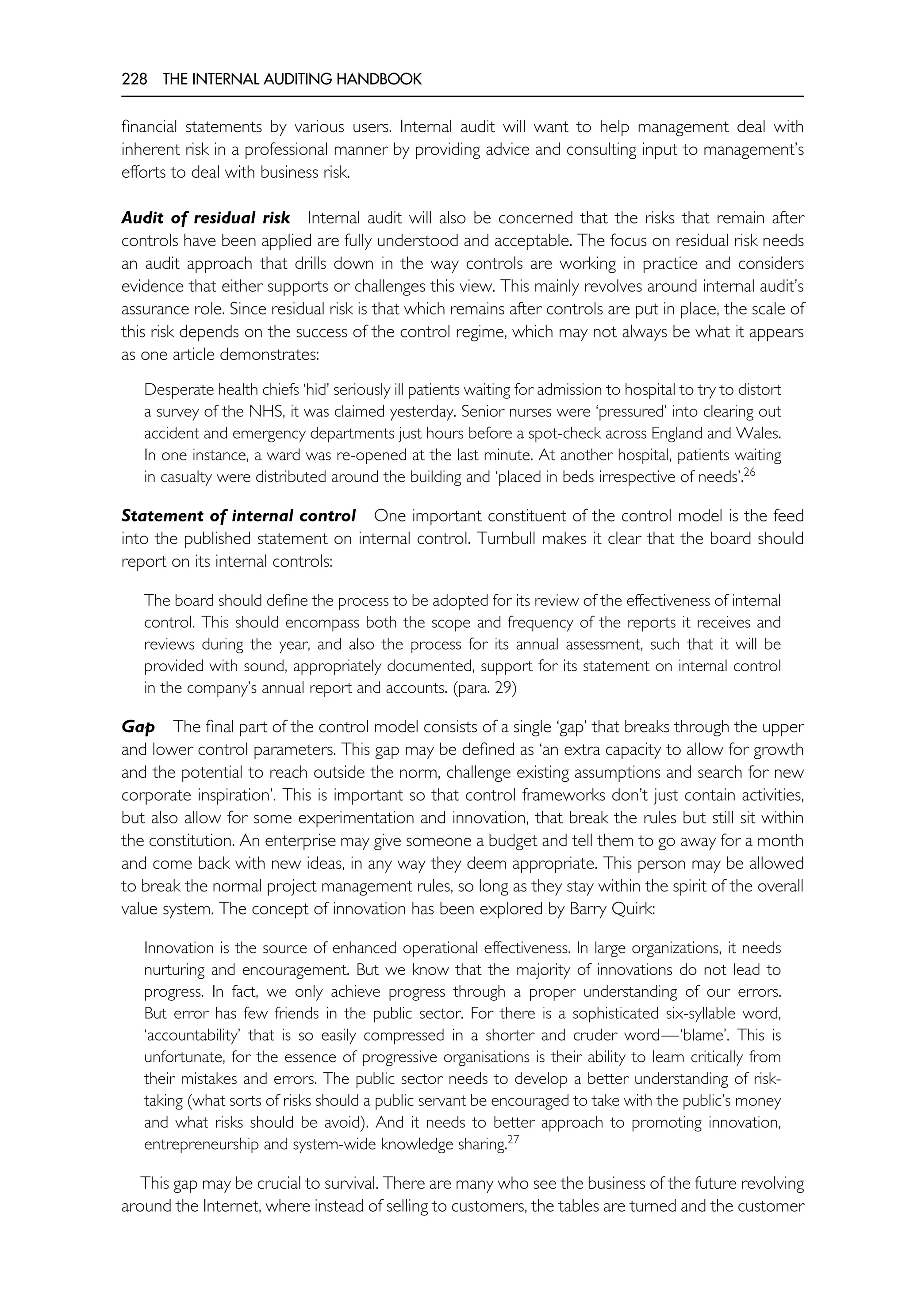

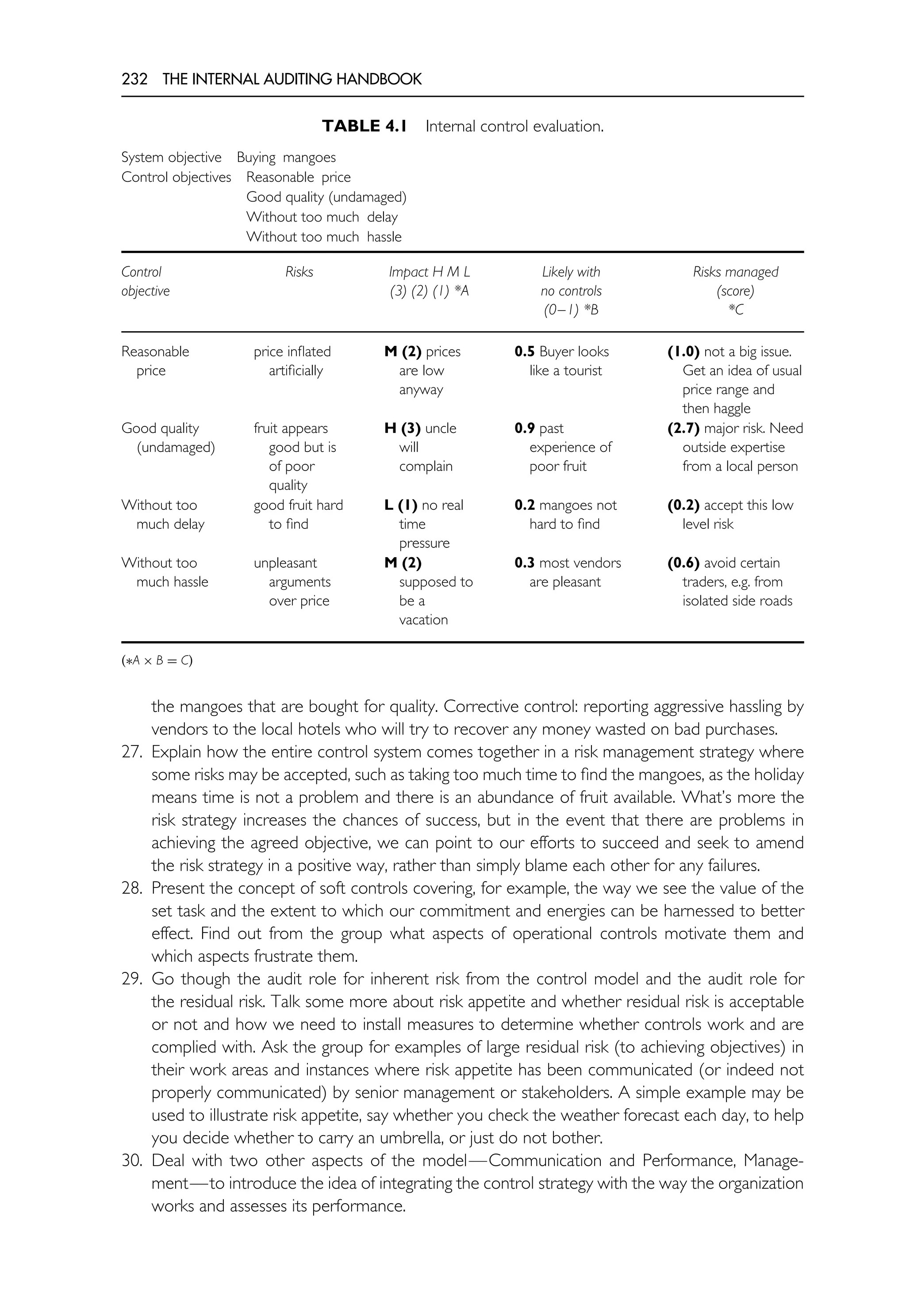

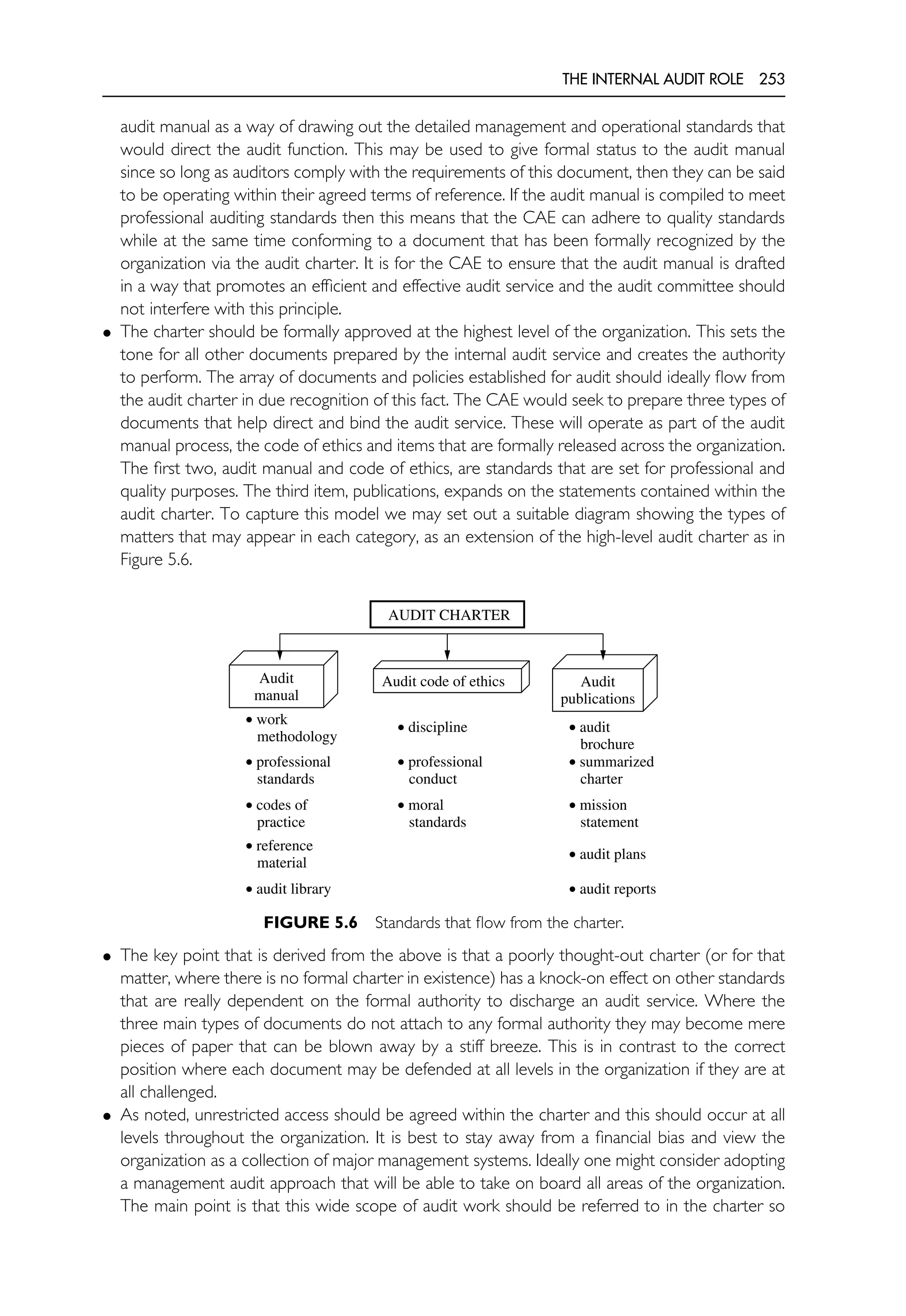

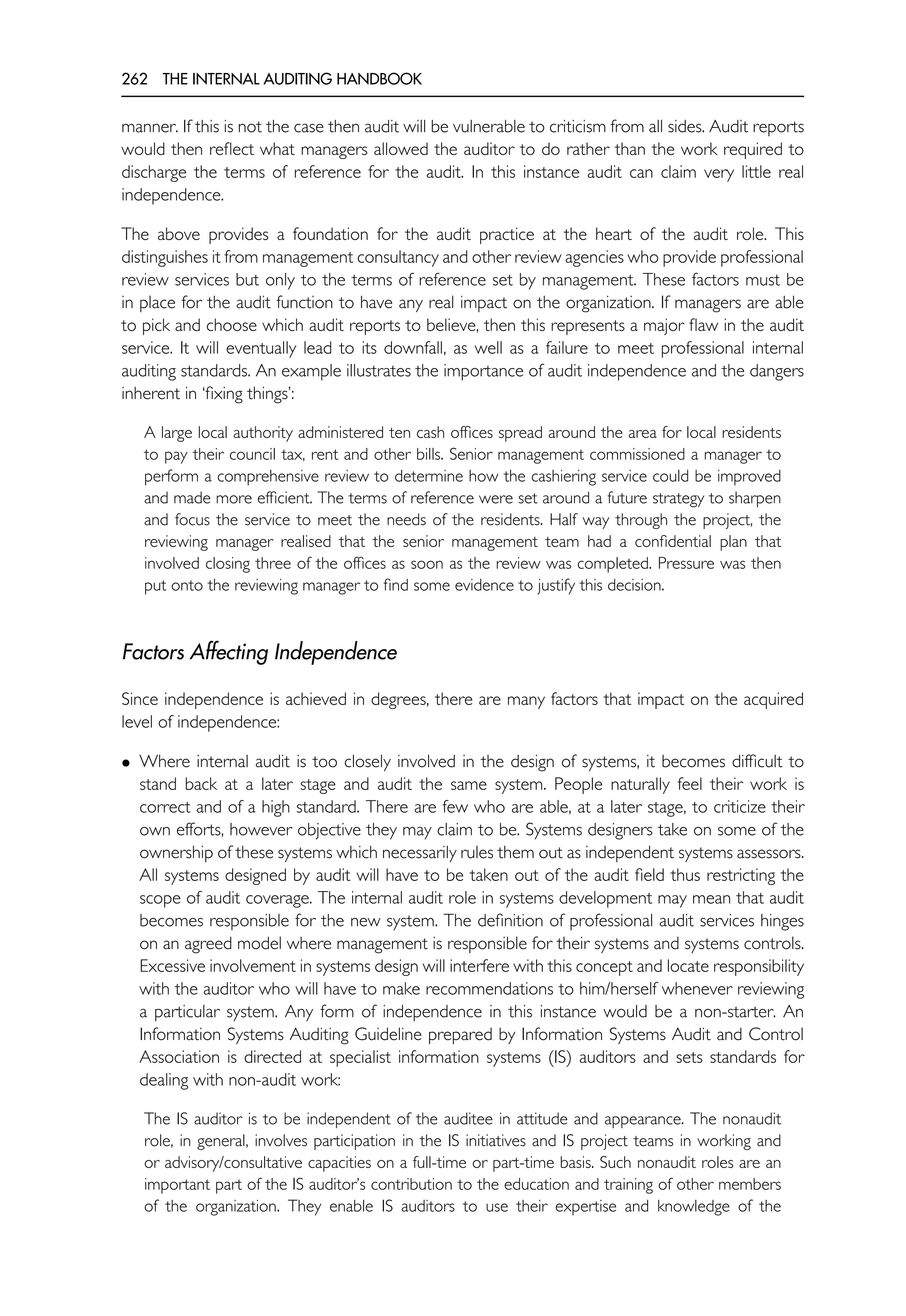

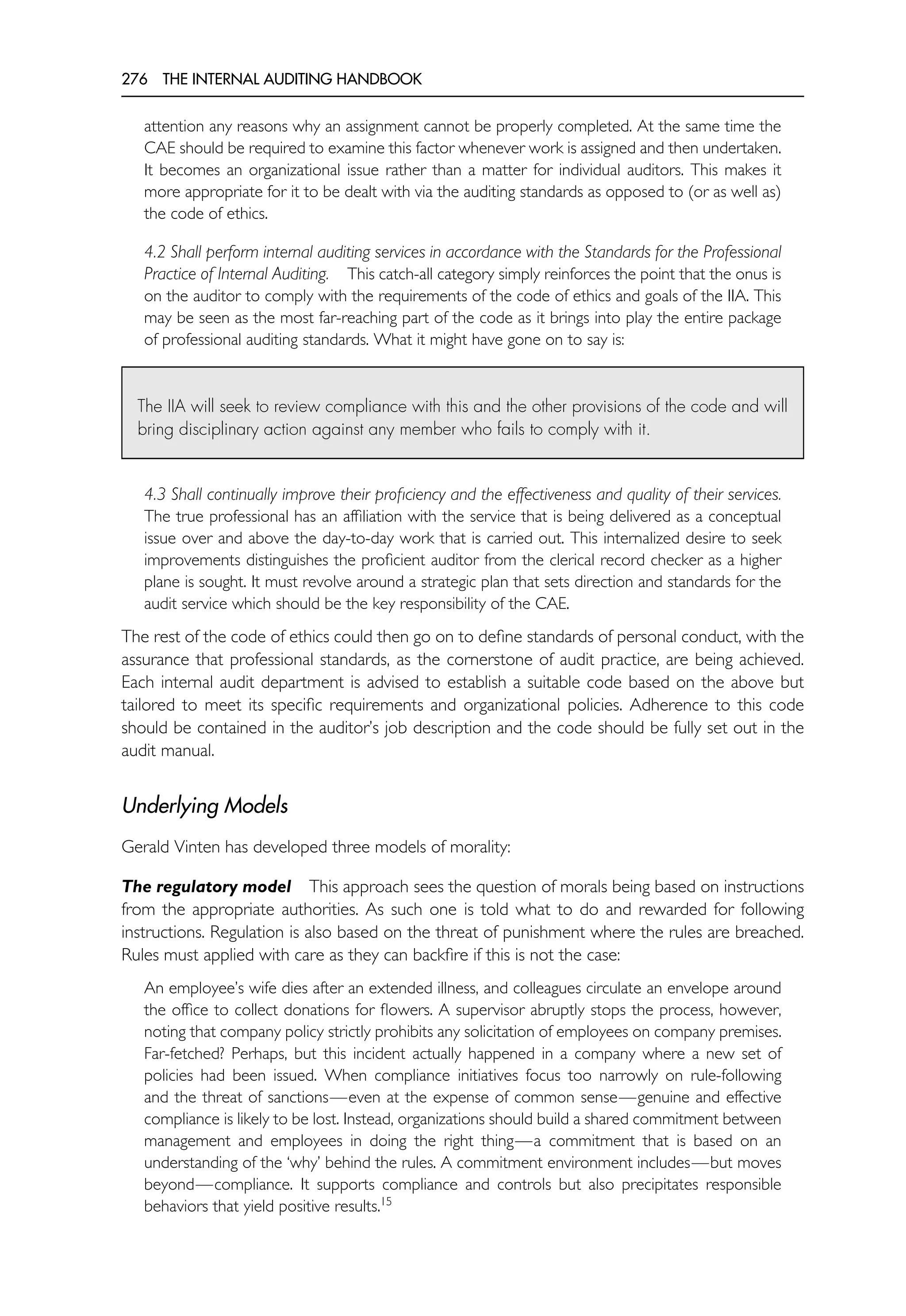

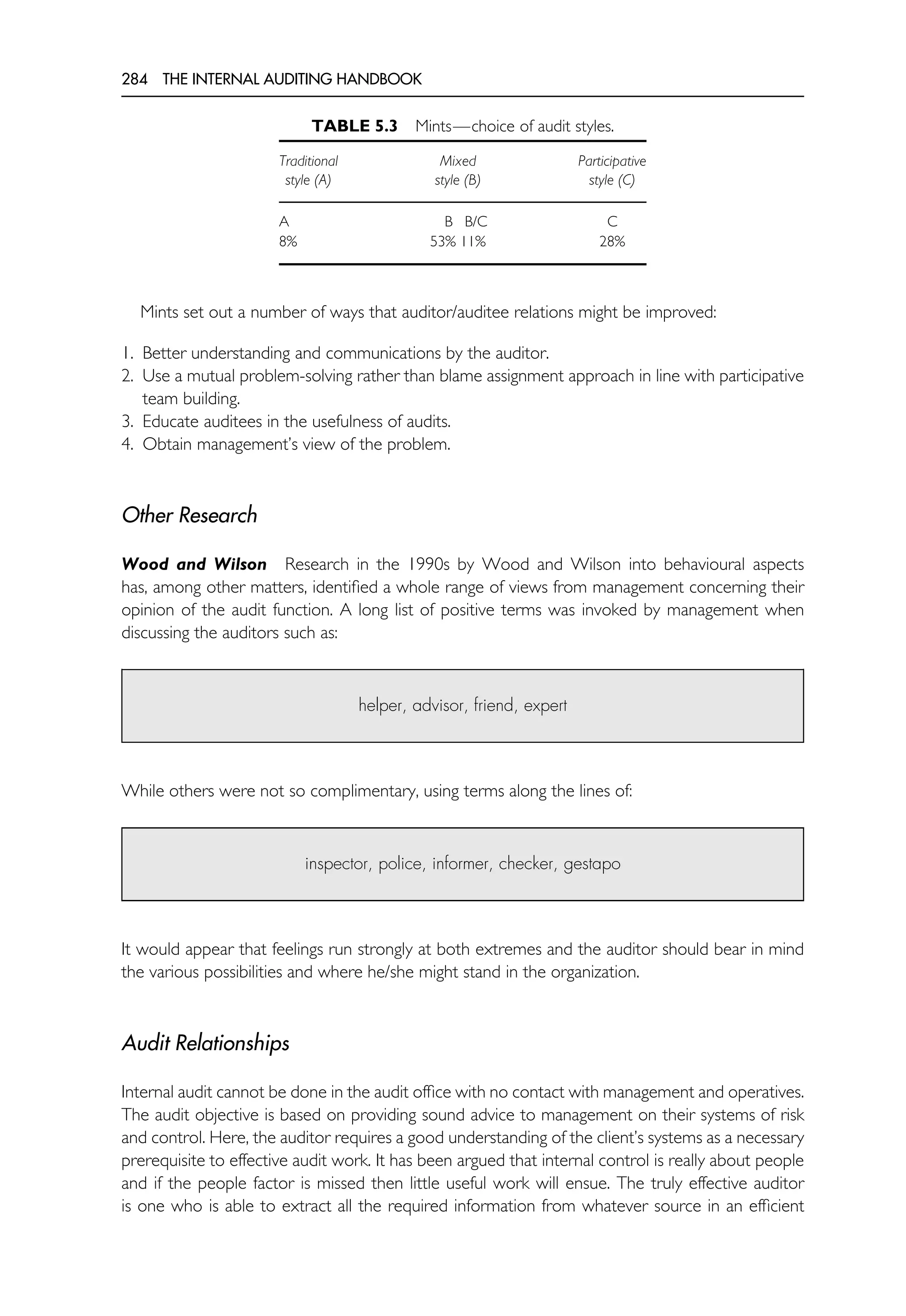

The auditor may aim to work at level [C], i.e. deal with controls over the operation and ensure

that these are adequate and adhered to. Work geared towards the operation itself [B] will take

the auditor to a higher level since an understanding of the operational processes provides the

foundation for a better audit. The management techniques [A] applied by senior officers act as

the ultimate control in any system. Work at this level will pay great dividends. [D] represents the

lowest level of audit work and if this approach is adopted, then, in contrast, it will reinforce the

low esteem in which the auditor is held by management. Ticking and checking cannot justify the

auditor’s claim to professionalism.

2. The audit snoop Line management and the various operatives may resent the audit as being

mainly based on management’s wishes to spy on them using audit staff for this unsavoury task.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/theinternalauditinghandbook-220527125740-de0fa305/75/The-Internal-Auditing-Handbook-pdf-299-2048.jpg)

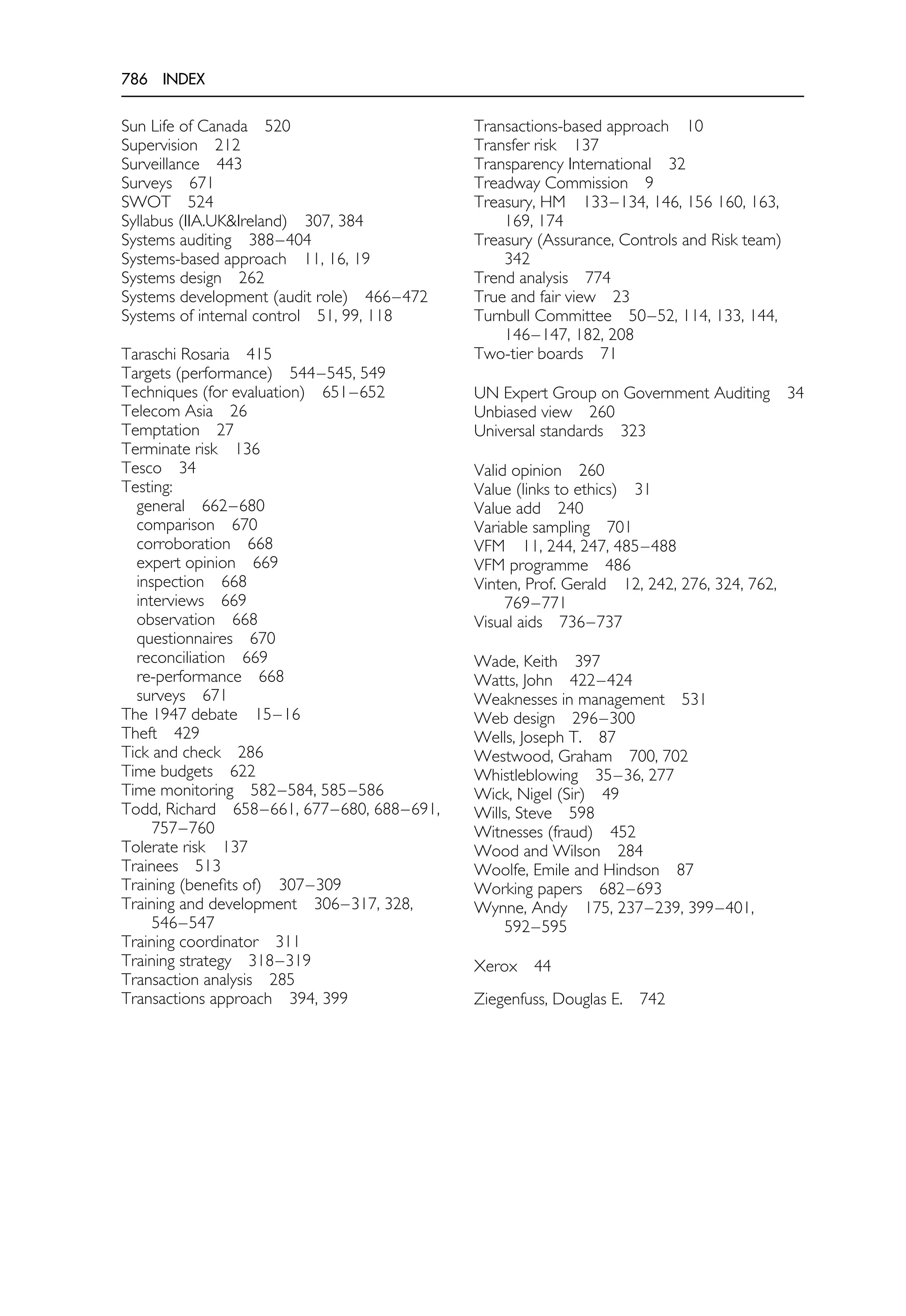

![THE INTERNAL AUDIT ROLE 287

Management of

the operation

AUDIT INPUT: [A]

The operation

AUDIT INPUT: [B]

AUDIT INPUT: [C]

Controls over

the operation

Information generated

by the operation

AUDIT INPUT: [D]

FIGURE 5.12 The implications of traditional tick and check.

It is management’s job to establish suitable controls over the areas that they are responsible for.

This includes installing information systems that provide feedback on the way staff are performing

so that corrective action may be taken whenever necessary. It is not acceptable for managers

simply to ignore this responsibility and rely on the annual internal audit to obtain information on

what their staff are doing. This is an incorrect interpretation of both management’s and audit’s

roles. The result is an arrangement whereby auditors are rightly seen as spies. Falling into this

trap damages the audit reputation which, if continued, may become irretrievable. Where internal

audit has not adopted this ill-conceived stance, then reliance may be given to staff at all levels in

the area under review that audit are not acting as moles. The response in this case is to explain

that audit reviews controls, not people; where people act as a control it is their role and not their

behaviour that is being considered. This technique cannot be applied where we do in fact act as

undercover agents for management.

3. Role of audit There are audits that are undertaken and completed with a final report

issued some time after the event that have little meaning to the operatives affected by the

work. Many see internal audit as part of the internal control that is centred on extensive testing

routines. Where the auditor cannot explain the precise audit objectives it may be seen more

as a punishment than a constructive exercise to assist management. This creates a mystique

surrounding the audit role that may be fostered by an uncommunicative internal auditor.

4. Interviewing An audit interview may be a highly pressurized event for a more junior

member of staff and if the auditor fails to recognize this, many barriers to communications may

arise. The attitude of the auditor may be a crucial factor in determining whether the interview is

successful or not. Audit objectives must be met but at the same time if the client’s expectations

are not satisfied (say in terms of clear explanations of the audit process) then the interviewee will

be dissatisfied.

5. Audit committee The relationship with the audit committee is a factor in the success of

the audit function. The committee constitutes a principal audit client, although the real support

for audit comes from middle management who run the systems on a day-to-day basis. Bearing

this in mind, the CAE will need to apply all his/her communications skills in forming a professional

platform for the audit role.

6. Poor cousin of external audit Where the internal auditors merely support the external

audit function, the relationship may leave little scope for professional development. Any prospec-

tive CAE should establish the precise position before accepting a new appointment and ensure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/theinternalauditinghandbook-220527125740-de0fa305/75/The-Internal-Auditing-Handbook-pdf-300-2048.jpg)