The document discusses using guided natural language and requirement boilerplates to elicit requirements in a semi-formal way that allows both humans and machines to build on their strengths, with guided natural language using defined terms to structure free text requirements and boilerplates providing a structured template to capture requirements in a consistent format. This hybrid approach aims to automate requirements elicitation and analysis as much as possible while still allowing for natural language to incorporate the human strengths in conceptualizing and communicating requirements.

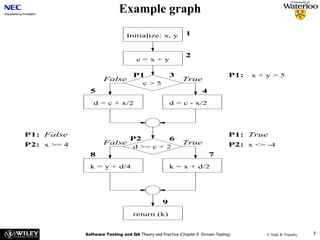

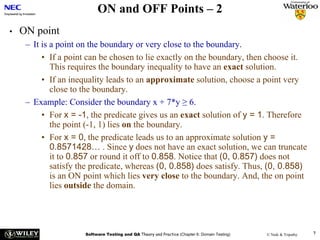

![Footprints – 1 Footprints – 2

E.g. scenario A uses 10 methods in class CAboutDlg Only classes are registered – e.g scenario [s3] uses

and 3 methods in Csettings Dlg classes C, J, R and U

Footprints – 3 Footprints – 4

Some problems: Based on the footprint table, we can make a

requirements-to-class trace table

• There might be scenarios that do not cover any

requirement – e.g. [s3]

• There are scenarios that belong to several

requirements, e.g. [s9]

Such scenarios will get separate rows in the trace

matrix and will be marked with an F (Fixed) or a P

(Probable), depending on how sure we are that a

certain class belongs to this scenario.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-30-320.jpg)

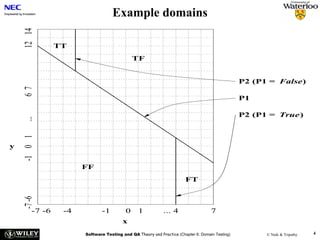

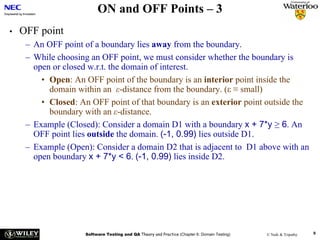

![Basic scenario pattern ‐ BSP

PreCondition == true / {Set activation time}

IsTimeout == true / [report fail]

Check for Check

precondition post-condition

PostCondition == true / [report success]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-242-320.jpg)

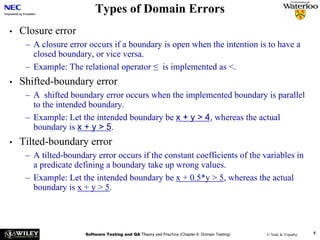

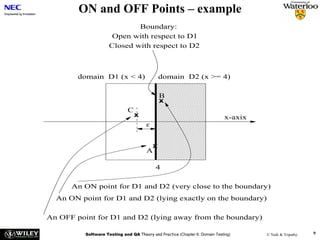

![Key‐event service pattern ‐ KSP

KeyEventOccurred / [SetActivationTime]

Check

precondition

PreCondition == true

Check for key Check

event post-condition

IsTimeout == true / [report fail]

PostCondition == true / [report success]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-244-320.jpg)

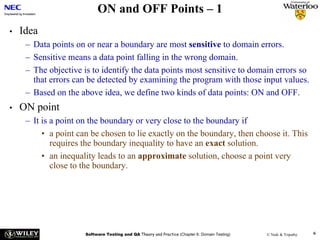

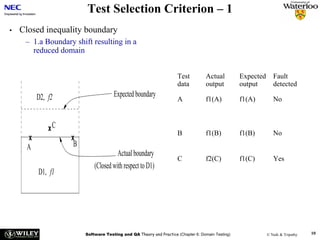

![Timed key‐event service pattern ‐ TKSP

KeyEventOccurred / [SetActivationTime]

Check

precondition

PreCondition == true

DurationExpired /

[report not exercised]

Check for key Check

event post-condition

IsTimeout == true / [report fail]

PostCondition == true / [report success]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-246-320.jpg)

![Round‐trip tree – small example

A

a[p1] / w

A B

a[p1] / w

B A

b[p2] / u

C

b[p2] / u

C

A B A ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-259-320.jpg)

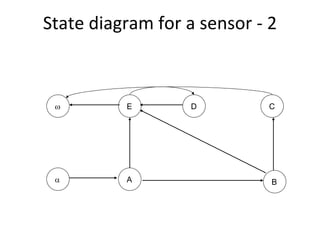

![Transitions

Each transition in a state diagram has the form

trigger‐signature [guard] / activity. All parts are

optional

• trigger‐signature: usually a single event that

triggers a potential change of state.

• guard: a Boolean condition that must be true

for the transition to take place.

• activity: an action that is performed during

the transition.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-260-320.jpg)

![Test description – 2

ID Start Event Condition Reaction New

state state

1 constructor - - A

2 A a p1 w C

3 C b p2 u A

a[p1] / w

A

A B

B A

b[p2] / u

C

a[p1] / w

b[p2] / u

C A B A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-262-320.jpg)

![Sneak path test description

ID Start Event Condition Reaction New

state state

1 constructor - - A

Error

2 A c p1 A

message

Error

3 A a p1 - false A

message

a[p1] / w

A

a[p1] / w

A B

b[p2] / u

a[p1] / w

C B A

b[p2] / u b[p2] / u

C A B A ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-264-320.jpg)

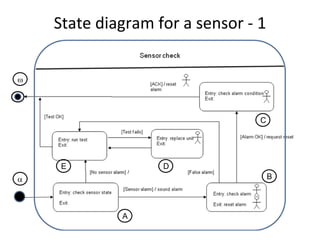

![Sensor round‐trip path tree

A

[no sensor alarm] / test [sensor alarm] / sound alarm

E B

[false alarm] / test [alarm OK / request reset]

[test fails] / replace

[test OK]

E

C

D

[test fails] / replace [ACK] / reset

/ test [test OK]

D

E

/ test

E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-267-320.jpg)

![Example

byte[] readFile() throws IOException {

...

final InputStream is = new FileInputStream(…);

...

while((offset < bytes.length) &&

(numRead = is.read(bytes,offset,(bytes.length-offset))) >=0)

offset += numRead;

...

is.close();

return bytes;

}

What could go wrong with this code?

• new FileInputStream() can throw FileNotFoundException

• InputStream.read() can throw IOException and

IndexOutOfBoundsException and can return -1 for end of file

• is.close() can throw IOException](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-394-320.jpg)

![Code containing array references

Code segment. The array b has 10 elements

i = x + 3;

IF b[i] <=5 THEN ,,,

ELSE …

We need three predicates:

b[x + 3] <= 5 – the original predicate

• x + 3 >= 1 – not below lower bound

• x + 3 <= 10 – not above upper bound](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-437-320.jpg)

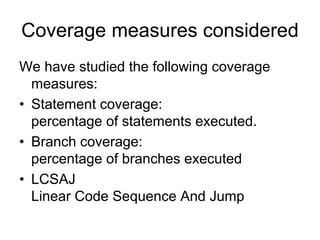

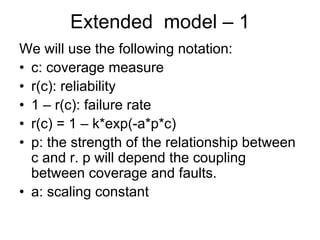

![Model – 1

We will use the following notation:

• c: a coverage measure

• r(c): reliability

• 1 – r(c): failure rate

• r(c) = 1 – k*exp(-b*c)

Thus, we also have that

ln[1 – r(c)] = ln(k) – b*c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-467-320.jpg)

![Model – 2

The equation ln[1 – r(c)] = ln(k) – b*c is of

the same type as Y = α*X + β.

We can thus use linear regression to

estimate the parameters k and b by doing

as follows:

1.Use linear regression to estimate α and β

2.We then have

– k = exp(α)

– b=-β](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-468-320.jpg)

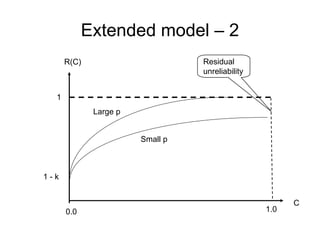

![Extended model - comments

The following relation holds:

ln[1 – r(c)] = ln(k) – a*p*c

• Strong coupling between coverage and

faults will increase the effect of test

coverage on the reliability.

• Weak coupling will create a residual gap

for reliability that cannot be fixed by more

testing, only by increasing the coupling

factor p – thus changing the usage

pattern.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-479-320.jpg)

If we use the expression on the previous

slide to eliminate C(n) we get

N 0 N (n) 1

1

N0 k ( nf ) p 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-482-320.jpg)

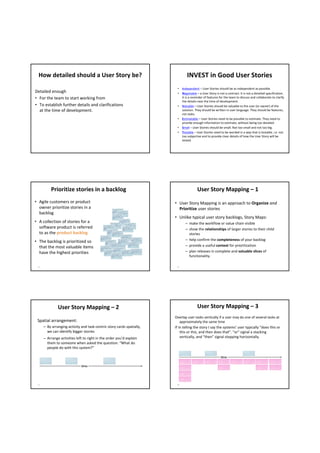

![User Story Cards have 3 parts User Story Template – 1

1. Description ‐ A written description of the user story for planning ‐ As a [user role] I want to [goal]

purposes and as a reminder so I can [reason]

- As a [type of user] I want to [perform some task] so

2. Conversation ‐ A section for capturing further information about the that I can [reach some goal]

user story and details of any conversations

3. Confirmation ‐ A section to convey what tests will be carried out to

confirm the user story is complete and working as expected Example:

• As a registered user I want to log in

so I can access subscriber‐only content

User Story Template – 2 User Story Description

Steps:

• Who (user role) • Start with a title.

• Add a concise description using the templates.

• What (goal) • Add other relevant notes, specifications, or sketches

• Why (reason) • Before building software write acceptance criteria

• gives clarity as to why a feature is useful

(how do we know when we’re done?)

• can influence how a feature should function

• can give you ideas for other useful features

that support the user's goals

Example: Front of Card Example: Back of Card](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-504-320.jpg)

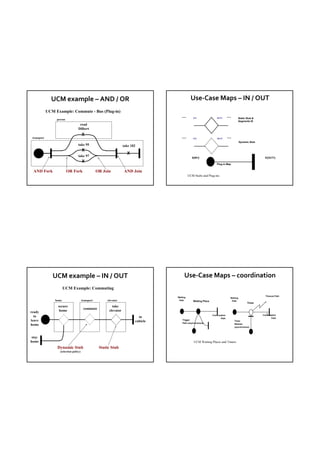

![Use-Case Maps Use-Case Maps – path

Definition: A visual representation of the requirements Start

Point

Path End

Point

of a system, using a precisely defined set of symbols for

responsibilities, system components, and sequences.

… … Responsibility

Links behavior and structure in an explicit and visual

way … … Direction Arrow

UCM paths: Architectural entities that describe causal … … Timestamp Point

relationships between responsibilities, which are bound … …

to underlying organizational structures of abstract Failure Point

components. … …

Shared Responsibility

UCM paths are intended to bridge the gap between UCM Path Elements

requirements (use cases) and detailed design

TDT 4242 TDT 4242

Use Case Maps example - path Use‐Case Maps – AND / OR

Mainly consist of path elements and components

UCM Example: Commuting OR-Fork

& Guarding … …

Conditions

[C1] OR-Join

home transport elevator [C2]

… … … …

secure take [C3]

ready

home

commute

elevator … …

to in

leave X X X

cubicle … …

home AND-Fork AND-Join

… … … …

… …

Basic Path Responsibility Point Component UCM Forks and Joins

(from circle to bar) (generic)

TDT 4242](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-517-320.jpg)

![Use Case Map Use Case Maps – example 1

Dynamic Structures

Contains pre‐conditions

Generic UCM Example or triggering causes

slot A Slot bars

representing

create create (component)

start post‐conditions

+

+ or

path traces through a system resulting effects

pool A move out of objects to explain a causal

slot B sequence, leaving behind a

+ visual signature.

move into move into

copy Pool Example of Use Case map • causal chains of responsibilities

- (component) (crosses, representing actions,

tasks, or functions to be

destroy pool B performed)

- • Responsibilities are normally

• A component is responsible to perform the action, task, or

bound to component when the

end function represented by the responsibility.

destroy cross is inside the component

• Start points may have preconditions attached, while

Dynamic Responsibilities and Dynamic Components responsibilities and end points can have post-conditions.

TDT 4242

Use Case Maps – example

The influence of chosen elements User

[not requested]

[moving]

moving

The elements we choose to include in our door close

motor up

model will decide the use case map but will below

decide on

direction motor down

above

not necessarily influence the actions needed. [stationary]

[requested]

The following examples are meant to in

elevator

add to list

motor

no requests stop

illustrate this. door

[more requests] open

Two elements are always needed: [else]

door

closing-delay

remove

at requested from list

User – requesting service floor

Arrival sensor – indicates when the elevator The elevator control system case study is adapted from Hassan

Arrival Sensor

Gomaa's Designing Concurrent, Distributed, And Real-Time

arrives at the chosen floor. Applications with UML (p459-462), copyright Hassan Gomaa 2001,

published by Addison Wesley. Used with permission.

approaching

floor

Select Destination](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-519-320.jpg)

![Model 1 – scheduler Model 1 – Use Case Map

User Scheduler

User Scheduler Arrival Sensor down [requested] Arrival Sensor

up [not requested]

[not requested] [requested] moving approaching

approaching select floor

down floor

up at floor elevator

select moving

at floor elevator below already Elevator

Elevator above add to on list

list decide on door

direction close

below in [on list]

above elevator

add to [else]

list stationary-

in at requested memory motor

elevator floor up

motor

door down

closing-delay

at requested remove from list

floor remove from list

motor Service Personnel

switch on motor

stop stop

door open Arch. Alternative (I) door open

Model 2 – scheduler and status & plan Model 2 – Use Case Map

User

User Scheduler Status & Plan

Status & Plan down

up Scheduler [not requested] [requested]

select [not requested] [requested] Arrival Sensor

down elevator select Arrival Sensor

up elevator Elev. Control

at floor

already approaching

Elev. Mgr Elev. Control on list moving floor

at floor below Elev. Mgr

above [on list]

Elevator

decide on Elevator

in direction

below [else] door

elevator close

above Status & Plan Status & Plan

stationary-

add to memory

in list

elevator add to at requested

door motor

list floor

closing- up

motor

delay down

remove

from list

at requested remove

floor from list motor Service Personnel

stop switch on

motor

stop

Service Personnel

switch on door open Arch. Alternative (II) door open](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-520-320.jpg)

![Requirements

and

Testing

TDT

4242

Exercise

1:

Consider

the

following

goals

in

an

Adaptive

Cruise

Control

system

for

vehicles

stated

below:

a) Identify

the

combination

of

sub-‐goals

that

would

jointly

contribute

to

each

of

the

goals.

b) Build

a

refinement

graph

showing

low-‐level

and

high-‐level

goals,

requirements,

assumptions,

domain

properties

and

associated

agents.

Hint:

Identify

behavioural

goals

and

soft

goals.

Identify

functional

and

non-‐functional

goals.

Goal

acc:

control

basis

Source

[ISO15622]

Description

When ACC is active, vehicle speed shall be controlled automatically either to

• maintain

time

gap

to

a

forward

vehicle,

or

to

• maintain

the

set

speed

whichever speed is lower.

Goal

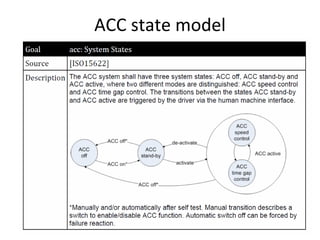

acc:

System

States

Source

[ISO15622]

Description

The ACC system shall have three system states: ACC off, ACC stand-by and

ACC active, where two different modes are distinguished: ACC speed control

and ACC time gap control. The transitions between the states ACC stand-by

and ACC active are triggered by the driver via the human machine interface.

*Manually and/or automatically after self test. Manual transition describes a

switch to enable/disable ACC function. Automatic switch off can be forced by

failure reaction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-686-320.jpg)

![Goal

acc:

control

preceding

vehicle

Source

[ISO15622]

Description

In case of several preceding vehicles, the preceding vehicle to be followed

shall be selected automatically.

Goal

acc:

functional

types

Source

[ISO15622]

Description

The ACC shall support a range of types:

1. Type

1a:

manual

clutch

operation

2. Type

1b:

no

manual

clutch

operation,

no

active

brake

control

3. Type

2a:

manual

clutch

operation,

active

brake

control

4. Type

2b:

active

brake

control

Notes:

1. To

be

completed

in

week

4

2. Need

to

understand

ISO

15622

–

Transport

information

and

control

systems:

Adaptive

Cruise

Control

Systems

–

performance

requirements

and

test

procedures.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-687-320.jpg)

![Side 2 av 11

Introduction

In this exam you can score a maximum of 70 points. The rest of the total possible score of 100

points for the semester comes from the compulsory exercises.

If you feel that any of the problems require information that you do not find in the text, then

you should

• Document the necessary assumptions

• Explain why you need them

Your answers should be brief and to the point.

Problem 1 – Requirements engineering (20 points)

Toga Islands airspace is divided into four zones (centres), and each zone is divided into

sectors. Also within each zone are portions of airspace, about 50 miles (80.5 km) in diameter,

called TRACON (Terminal Radar Approach CONtrol) airspaces. Within each TRACON

airspace there is a number of airports, each of which has its own airspace with a 5-mile (8-

km) radius.

For jet powered airliners flying within Toga airspace, the cruising altitudes typically vary

between approximately 25,000 feet and 40,000 feet. All other engines are only allowed to fly

at a cruising altitude below 25,000 feet. Allowable cruising altitude is dependent on the speed

of the aircraft.

Consider the goal model fragment of an air traffic control system for Toga Islands in the

diagram in appendix 1. The parent goal roughly states that aircraft routes should be

sufficiently separated. The refinement is intended to produce sub-goals for continually

separating routes based on different kinds of conflicts that can rise among routes. The goal

Achieve[RouteConflictsPredicted] roughly states that the air traffic control system should be

able to predict route conflicts associated with aircraft flying within Toga airspace.

1a –– 15 points

1. Identify the parent goal of the goal Maintain[SufficientRouteSeparation].

Maintain[SafeFlight] is considered to be the right answer. With logical reasons, marks

should also be given for answers such as: Achive[RouteOptimisation]

Maintain[RouteEfficiency]

2. Based on the description provided above, identify two refinement nodes from the sub-goal

Achieve[RouteConflictsPredicted].

Ideally it is expected that students will use the parameters in the description above (zone,

sector, airport_airspace, cruising_altitute, type_of_engine, speed_of_aircraft) to derive

subgoal, concrete requirement, design constraint or an expectation. Example:

• Maintain[WorstCaseConflictDistance] (sub-goal)

• Achieve[CompareSpeedofAircraft if same zone and same cruising_altitude] (concrete

requirement)

• Achieve[CompareEngineType if same sector and cruising_altitude] (concrete

requirement)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-699-320.jpg)

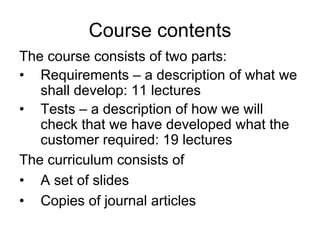

![Side 6 av 11

α

A

cancelled

term started

ω B

class ended

student dropped

[size > 0]

B C

closed

student dropped

[size = 0]

ω ω

ID Start state Event Condition Result New state

1 α Constructor - - Α

2 A Cancelled - - ω

3 A Term started - - B

4 B Student dropped Size = 0 - ω

5 D Student dropped Size > 0 - B

Note that the table is just an example – it is not complete.

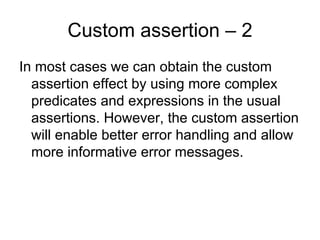

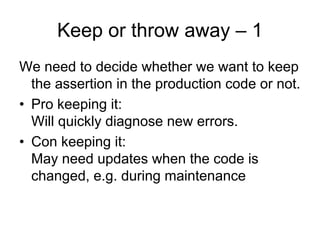

Problem 3 – Testing management (30 points)

Our company has a large amount of expertise on testing. Thus, testing other companies’

products has become a major source of income for us. Our testers are especially good at using

all types of assertions during testing.

A large company that specializes in development of software for industrial automation has put

a large test job out for tender. The code will be developed in Java. The test job contains the

following activities:

• Testing of all classes before integration. Unit testing of individual methods has already

been done

• Integrating and testing the subsystems

• Testing the total system, consisting of all the subsystems integrated.

• Construct the first version and necessary infrastructure for a regression test.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tdt4242-110828132951-phpapp02/85/Tdt4242-703-320.jpg)