This document provides Kenya's integrated guidelines for tuberculosis, leprosy and lung disease from 2021. It covers approaches to active case finding for tuberculosis, diagnosis and treatment of drug susceptible and drug resistant tuberculosis in adults and children. It also includes guidance on management of latent tuberculosis, tuberculosis infection control, chronic lung diseases including asthma and COPD, as well as leprosy diagnosis and treatment. The guidelines are intended to provide a comprehensive resource for healthcare workers on integrated patient-centered care for tuberculosis, leprosy and lung health in Kenya.

![Integrated Guideline for Tuberculosis,

Leprosy and Lung Disease | 2021

97

The TB-exposed neonate is highly vulnerable and may rapidly progress to symptomatic

and severeTB disease. Symptoms and clinicalsigns ofneonatalTB are usuallynonspecific

and examples are shown in the table below:

Table 4.21: Signs and Symptoms of Neonatal TB

Symptoms Clinical signs

Lethargy Respiratory distress

Fever Non-resolving ‘pneumonia’ or respiratory infection

Poor feeding Hepatosplenomegaly

Low birth weight Lymphadenopathy

Poor weight gain Abdominal distension

Clinical picture of ‘neonatal sepsis’

The diagnosis of TB should be included in the differential diagnosis of a child with

neonatal sepsis, poor response to antimicrobial therapy, congenital infections, and

atypical pneumonia. The most important clue to the diagnosis of neonatal TB is a

maternal history of TB or any contact with a person with a chronic cough.

Clinical evaluation of the infant in the setting of suspected congenital TB should include

TST and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), HIV testing, chest radiograph, lumbar

puncture, cultures (blood and respiratory specimens), and evaluation of the placenta

with histologic examination (including acid-fast bacilli [AFB] staining culture). The TST in

newborns is usually negative, but an IGRA test may be positive in some cases.

4.8.2 Management of the Asymptomatic Neonate Exposed to

Maternal TB

If a neonate is born to a mother with TB or is exposed to a close contact with TB, TB

Preventive Therapy (TPT) should be given for 6 months once TB disease has been ruled

out. BCG can be given 2 weeks after completion of TPT. It is not necessary to separate

the neonate from the mother. However, the mother should be educated on infection

prevention control measures.

Breastfeeding is not contraindicated for a child whose mother has TB

Neonates born to mothers with MDR-TB or XDR-TB should however be referred for TB

screening and management. TPT should not be given. Infection control measures such

as the mother wearing a mask are required to reduce the likelihood of mother to child

transmission of DR TB.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tbguidelines-2021-final-230131152514-1054a7a0/85/TB-Guidelines-2021-Final-pdf-113-320.jpg)

![Integrated Guideline for Tuberculosis,

Leprosy and Lung Disease | 2021

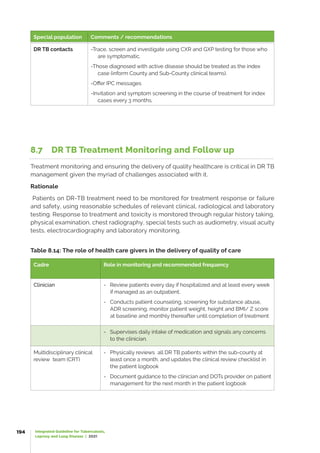

234

Appropriate Disinfectants: Phenolic agents (5% phenolin water or a phenolic disinfectant

product diluted as per label) are excellent disinfectants for cleaning up sputum spills

and for decontaminating equipment and single use items prior to disposal. Fresh

household bleach (5% sodium hypochlorite) diluted 1:10 with water can also be used as

a general disinfectant. Bleach solution works well for cleaning up blood spills; however,

it is somewhat less effective than phenolic agents against TB. It is important that bleach

dilutions be made fresh since it loses potency with time. 70% alcohol is a good agent for

cleaning bench tops.

Safe disposal of infectious waste

After smears have been processed, place all infected materials including closed sputum

containers in a biohazard bag (polyethylene, if available). Discard applicator sticks

used for smearing immediately after use. Since all sputum specimens are considered

potentially infectious, treat all materials in the procedure as contaminated.

Discard specimens by one of the following methods:

•● Incineration

•● Burying

•● Autoclaving

To protect the surrounding population, the laboratory must dispose of waste safely.

Incineration is usually the most practical way for safe destruction of laboratory waste.

If incineration cannot be arranged, discard the waste in a deep pit of at least 1.5-meter

depth. If an autoclave is available, place infected materials inside and follow procedures

for safe and adequate sterilization.

Ventilated Cabinets

Ventilated Cabinets include Laboratory Fume Hoods and Biological Safety Cabinets.

The details of these devices follow.

1. Laboratory Fume Hoods

The least expensive ventilated cabinet for laboratories is the Laboratory Fume Hood.

This type of environmental control is designed for the purpose of worker protection (no

protection of the environment or the product [specimen/ culture]). These devices, like

Biological Safety Cabinets, are designed to minimize worker exposures by controlling

emissions of airborne contaminants (including aerosols) through the following:

• The full or partial enclosure of a potential contaminant source

• The use of airflow velocities to capture and remove airborne contaminants near

their point of generation.

• The use of air pressure relationships that define the direction of airflow into the

cabinet](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tbguidelines-2021-final-230131152514-1054a7a0/85/TB-Guidelines-2021-Final-pdf-250-320.jpg)

![Integrated Guideline for Tuberculosis,

Leprosy and Lung Disease | 2021

290

• Give short course oral prednisone 40mg daily for 7 days if patient has severe

COPD

• High dose (800pg) inhaled corticosteroids are effective in patients with severe

COPD with more than 2 infective exacerbations per year

• Give influenza vaccine yearly and pneumococcal vaccine 5 yearly

• Identify and manage complications. Treat fluid retention with a low dose diuretic.

• Encourage patient to exercise daily e.g. walking, gardening, household chores,

using stairs instead of lifts etc.

• Review patients every 3-6 months if stable.

13.3 Post-Tuberculosis Lung Disease (PTLD)

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.7 billion people are infected

with M. tuberculosis globally and approximately 54 million people survived Tuberculosis

(TB) between 2000 and 2017 alone. Kenya for instance notified 96,478 patients with TB

in 2018 and successfully treated 84% of them. There is increasing evidence of long-

term respiratory complications following TB in a proportion of these patients affecting

their quality of life. For many persons with tuberculosis, a microbiological cure is the

beginning, not the end of their illness.

Post TB Lung Disease (PTLD) is defined as chronic respiratory abnormality with or without

symptoms attributable, at least in part, to previous pulmonary TB.

There is evidence that over 60% of patients still have symptoms after completion

of TB treatment, over 80% have radiological sequalae, over 30% have spirometric

function test abnormalities and over 40% have bronchiectasis (Meghji J, et al 2020

[https:/

/thorax.bmj.com/content/75/3/269]).

Patients with PTLD may present with persistence of symptoms or decline in lung function

despite successful completion of treatment or cure.

Patients presenting with respiratory complaints and have recently completed

TB treatment (and who may be erroneously considered as TB relapse) should

be thoroughly evaluated for post-TB lung disease and/ or other forms of lung

conditions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tbguidelines-2021-final-230131152514-1054a7a0/85/TB-Guidelines-2021-Final-pdf-306-320.jpg)

![Integrated Guideline for Tuberculosis,

Leprosy and Lung Disease | 2021

299

Table 13.13: Signs and Symptoms of Aspergillosis

Type of illness Signs / symptoms Predisposing condition

Allergic reaction

(allergic

bronchopulmonary

aspergillosis)

●• Fever

●• A cough that may bring up blood

or plugs of mucus

●• Worsening asthma

Develops in asthma or cystic

fibrosis

Aspergilloma ●• Normal initially

●• A cough that often brings up

blood (haemoptysis)

●• Wheezing

●• Shortness of breath

●• Unintentional weight loss

●• Fatigue

Emphysema, tuberculosis or

advanced sarcoidosis,

Invasive aspergillosis

(Most severe form and

fatal)

Signs and symptoms depend on

which organs are affected, Generally:

• Fever and chills

• A cough that brings up blood

(haemoptysis)

• Shortness of breath

• Chest or joint pain

• Headaches or eye symptoms

• Skin lesions

In people whose immune systems

are weakened as a result of

cancer chemotherapy, bone

marrow transplantation or a

disease of the immune system to

the brain, heart, kidneys or skin

Table 13.14 Diagnosis of Aspergillosis

Diagnostic spectrum

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

(ABPA)

Invasive aspergillosis

(Chronic necrotizing

Aspergillus pneumonia)

Aspergilloma

Laboratory testing

Major:

Blood: CBC for Eosinophilia.

-Skin test - positive result for A. fumigatus

-Marked elevation of the serum

immunoglobulin E (IgE) level to greater than

1000 IU/dL

- Aspergillus Precipitin test: positive

results for Aspergillus precipitins (primarily

immunoglobulin G [IgG], but also

immunoglobulin A [IgA] and immunoglobulin

M [IgM])

Demonstration of the

organism in sputum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tbguidelines-2021-final-230131152514-1054a7a0/85/TB-Guidelines-2021-Final-pdf-315-320.jpg)