This document provides an overview of preparing to switch from Windows to Mac. Some key points:

- Reasons for switching include Mac stability, lack of viruses, ease of use, attractive software and details, and Apple's current success.

- Challenges include the work of switching habits, Macs sometimes seeming harder to use due to fewer resources than Windows, and connecting to Windows networks can be tricky.

- Tips for addressing challenges include slowing down during the transition, taking advantage of Apple Stores and Genius Bars for help, forming user groups, and realizing Macs typically need less support. Connectivity issues are a pain but Apple works to enable compatibility.

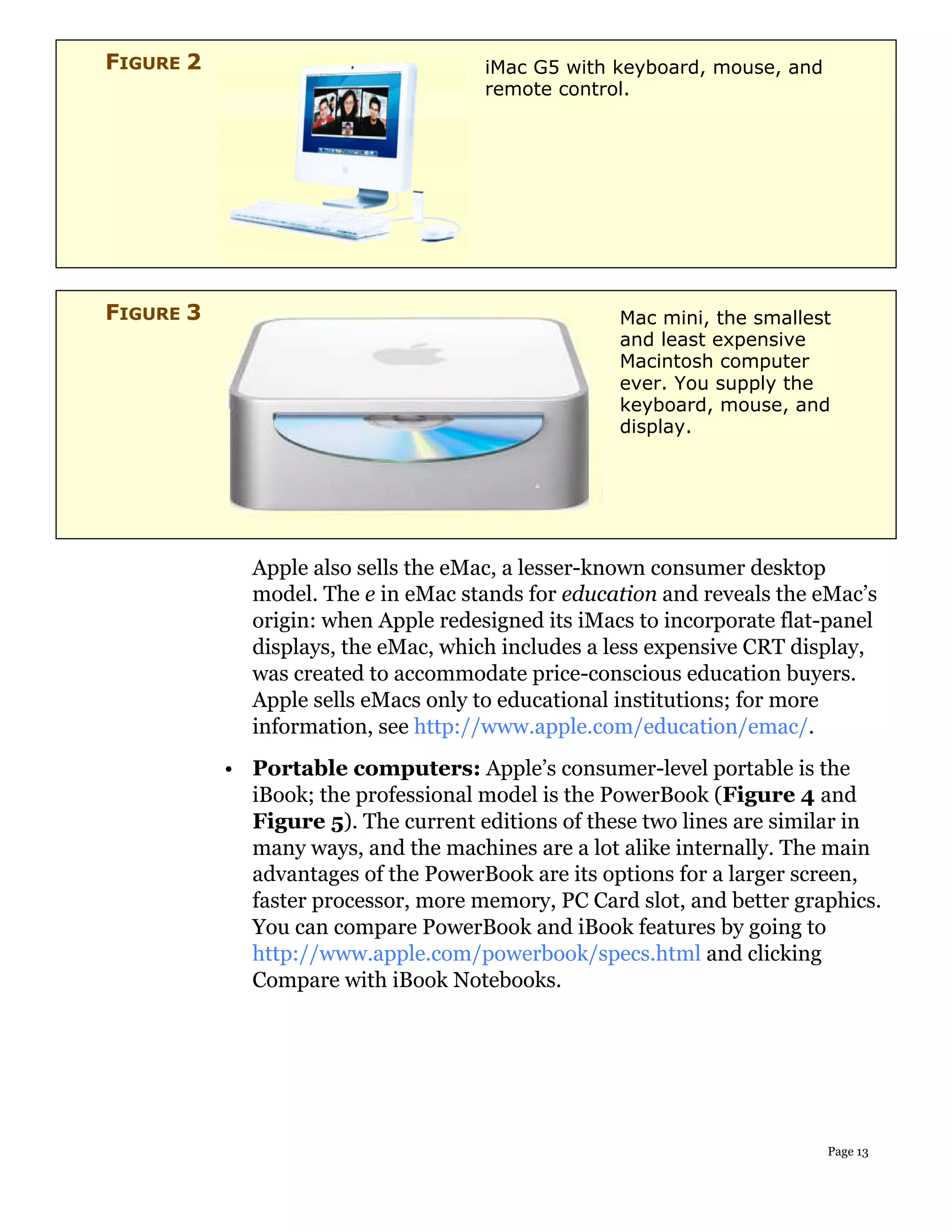

![FIGURE 4 The PowerBook is avail-

able in various screen

sizes: 12-, 15-, and 17-

inch. It includes nifty

features such as a backlit

keyboard and a trackpad

that can be used for

scrolling.

FIGURE 5 The iBook is the Power-

Book’s less expensive

cousin. It lacks a few of

the PowerBook’s features

and is available only in

12- and 14-inch screen

sizes, but it can cost

substantially less.

NOTE Although this general description of Apple’s Macintosh lines is

correct as of November 2005, Apple is always making new stuff, so

the product line is bound to change in the future. In particular, with

Apple’s transition to Intel processors just around the corner (see the

sidebar Switching to Intel), big changes might be afoot. (I don’t know

anything about Apple’s plans for new Macs, and [almost] nobody else

does either. Apple loves to surprise everyone and is notorious for its

secrecy. Of course, this vacuum of official information leads to a

flood of speculation and rumors about what Apple is up to. Rumor-

mongering is a popular pastime among Macintosh fans.)

For detailed information about selecting the right Mac for you,

I suggest that you read Take Control of Buying a Mac

(http://www.takecontrolbooks.com/buying-mac.html).

Page 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/takecontrolofswitchingtothemac1-0-100824141137-phpapp02/75/Take-control-of-switching-to-the-MAC-14-2048.jpg)