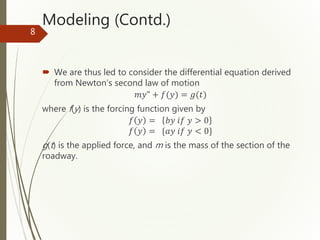

The document summarizes a study analyzing the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Suspension Bridge in 1940. The objectives were to model the collapse mathematically and simulate it in Matlab. The model treats the bridge cables as springs with different stiffness in tension and compression. The simulation shows the amplitude of oscillations increasing over time, contradicting the traditional explanation of resonance causing collapse. It concludes the large oscillations were not due to resonance.

![Modeling (Contd.)

We will assume that m= 1 kg, b= 4 N/m, a=1N/m, and g(t) =

sin(4t) N

Therefore we must solve initial value problem

𝑦" + 4𝑦 = sin 4𝑡 𝑦(0) = 0; 𝑦′(0) = 0.01

After solving above problem, we get the following solution

𝑦 𝑡 = sin 2𝑡 [

1

2

0.01 +

1

3

−

1

6

cos 2𝑡 ]

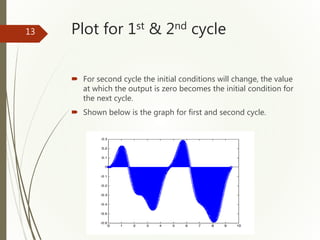

We note that the first positive value of t for which y(t) is again

equal to zero is 𝑡 = 𝝅/2, so above equation holds on [0, 𝝅/2]

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tacomanarrowbridgemath-180129175621/85/Tacoma-narrow-bridge-math-Modeling-9-320.jpg)

![Modeling (Contd.)

After t=𝝅/2, y becomes negative, so we must now solve the new

problem

𝑦" + 𝑦 = sin 4𝑡 𝑦(𝝅/2) = 0; 𝑦′(𝝅/2) = −(0.01 + 2/3)

Proceeding as previous, the solution of above problem is

𝑦 𝑡 = cos 𝑡[ 0.01 +

2

5

−

4

15

sin 𝑡 cos 2𝑡]

We note that the first positive value of t for which y(t) is again equal

to zero is 𝑡 = 3𝝅/2, so above equation holds on [0, 3𝝅/2]

Here our first cycle is completed, for next cycles the derived

problems will remain same but the initial conditions will change,

The first value at which the system is equal to zero is our initial

conditions for next interval.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tacomanarrowbridgemath-180129175621/85/Tacoma-narrow-bridge-math-Modeling-10-320.jpg)