This document provides an overview of software assurance (SwA) initiatives within the US federal government. It discusses how the Department of Homeland Security established the National Cyber Security Division Software Assurance Program to promote software security, integrity, and resiliency. It also describes the development of a common measurement framework to help organizations implement security best practices throughout the software development lifecycle. Finally, it analyzes security risks and mitigation strategies for Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems used in critical infrastructure through examples like the Stuxnet malware.

![SwA and SEC. INITIATIVES 5

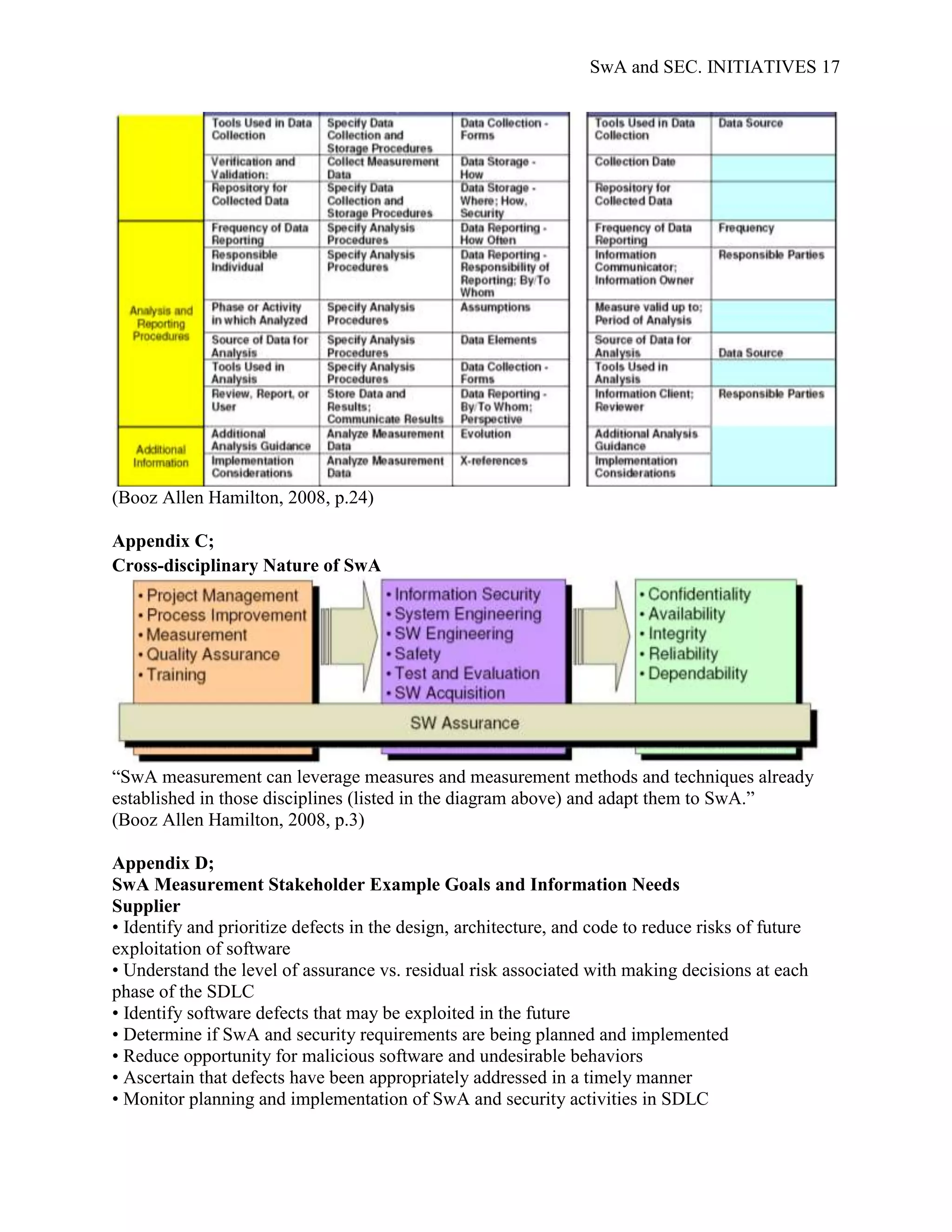

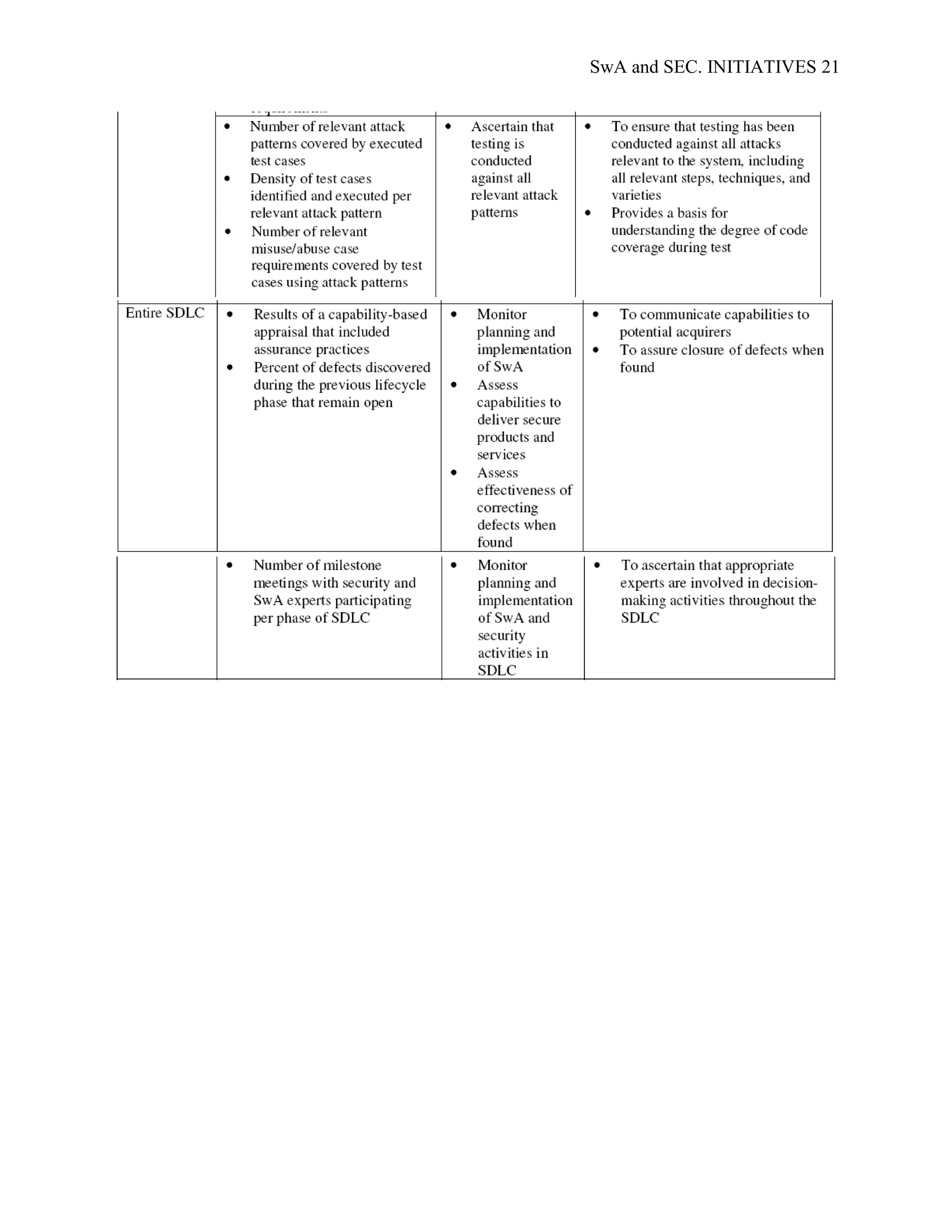

applicable to different stakeholders; Appendix D; SwA Measurement Stakeholder Example

Goals and Information Needs, provides examples of the security and data requirements of

generic SwA stakeholders. Examples of common SwA measurement methodologies, arranged by

stakeholder type, are presented in Appendix E; Example Measures for the Stakeholder Groups.

Once a set of manageable SwA measures have been established they should then be incorporated

into the organization‟s current security evaluation processes. Implemented measures can be

adjusted throughout the SDLC in order to best suit the security and evaluation needs of a project.

Appendix F; Basic Measures Implementation Process, further depicts the basic steps involved in

implementing the measurement framework.

When using the framework, good documentation practices are important to support

consistent and accurate data intake. Reliable data is necessary in order to efficiently use the

measurements for analysis. “Enumerations provide a common language that describes aspects of

SwA, such as weaknesses, vulnerabilities, attacks, and configurations, and by doing so enable

consistent and comparable measures.” (Booz Allen Hamilton, 2008, p.30) Enumerations support

a quantifiable data source therefore enabling more advanced measurements for SwA evaluation;

standard enumerations specific to SwA include Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE),

Common Control Enumeration (CCE), Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE)

[http://cwe.mitre.org/], and Common Attack Pattern Enumeration and Classification (CAPEC)

[http://capec.mitre.org/]. Enumeration measurements should be adapted the organizational goals,

requirements, and SwA needs. Since the framework provides both quantitative and qualitative

measurements it is possible to evaluate security standards and track progress in a consistent and

realistic manner. Once data has been gathered and analyzed, the documented measurements can

be used to justify changes in security policy or protocols as well as in resource allocation. It is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/swaandsec-initiativeslandolfi-120621145709-phpapp01/75/US-Government-Software-Assurance-and-Security-Initiativesi-5-2048.jpg)

![SwA and SEC. INITIATIVES 6

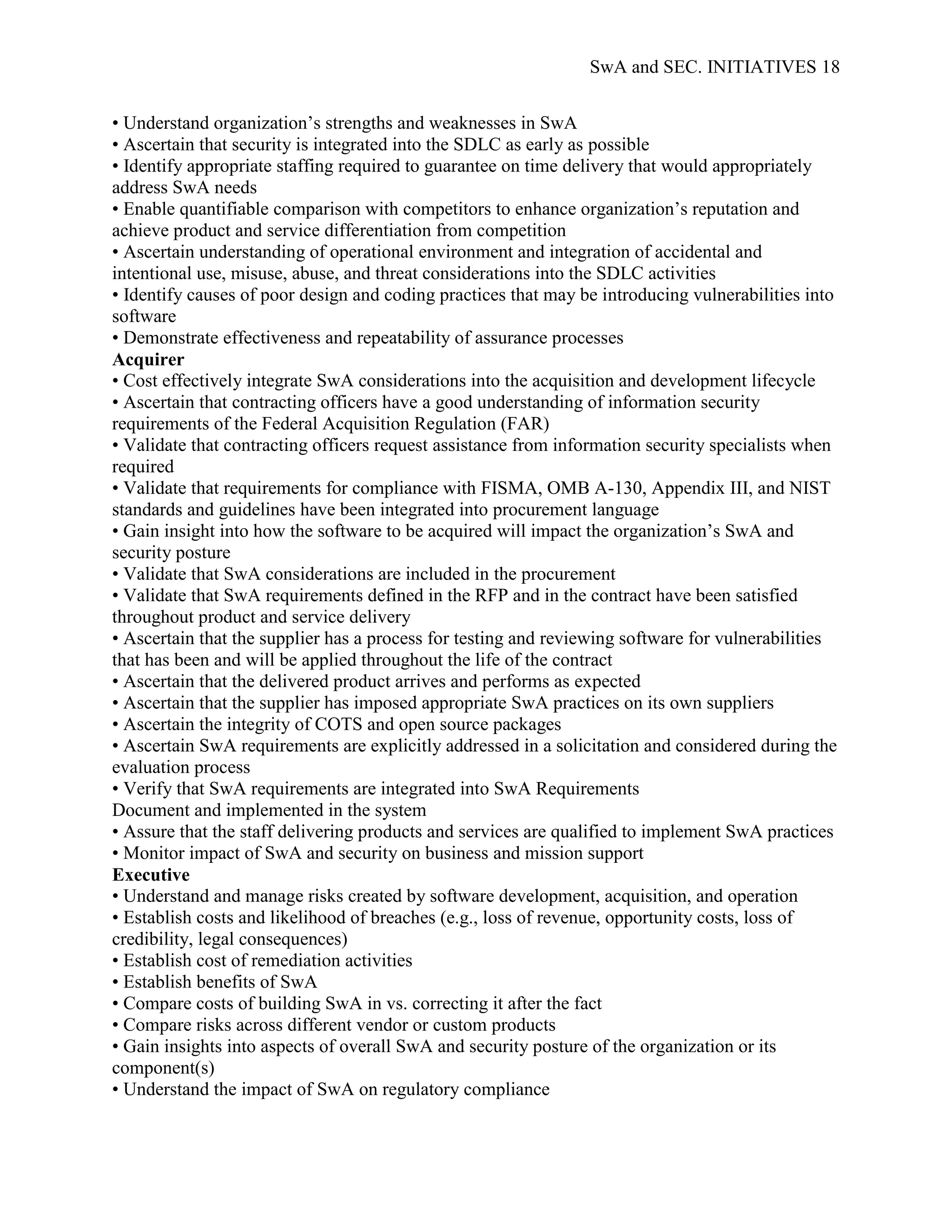

beneficial to incorporate SwA measurements into the budget allocation of a risk management

strategy in order to promote budget implementation designed to best achieve the desired risk

mitigation results.

To be successful SwA measures must be present in all stages of the SDLC including

acquisition and outsourcing, development, lifecycle support, measurement and information

needs. The DHS NCDS initiatives to build security into the SDLC are presented in the process

agnostic approach, specifically as best practice touchpoints resulting in software artifacts.

Appendix G; Process Agnostic Approach exhibits the DHS NCDS recommended SwA and

security touchpoints to incorporate into secure software lifecycle processes. Additional SwA

related documents and resources are available for free downloading via the Department of

Homeland Security National Cyber Security Division website [https://buildsecurityin.us-

cert.gov/swa/].

SwA is becoming increasingly important to national security efforts since the majority of

software dependent services are virtually interconnected. For example, cyber-communication

systems such as Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) are highly vulnerable; the

probability of a cyber-attack on critical infrastructure (CI) is definite. The ability to control CI

functionality makes energy management systems (EMS), such as SCADA, among the most

likely target for an asymmetric attack; unauthorized access to SCADA is a major vulnerability

since these systems basically control the power systems. This type of attack is relatively cheap to

execute and is associated with catastrophic failures and large scale damages. Additionally,

threats to SCADA dependent systems expose the vulnerability of the increasing

interdependencies between CI sectors as well as the SCADA system.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/swaandsec-initiativeslandolfi-120621145709-phpapp01/75/US-Government-Software-Assurance-and-Security-Initiativesi-6-2048.jpg)

![SwA and SEC. INITIATIVES 13

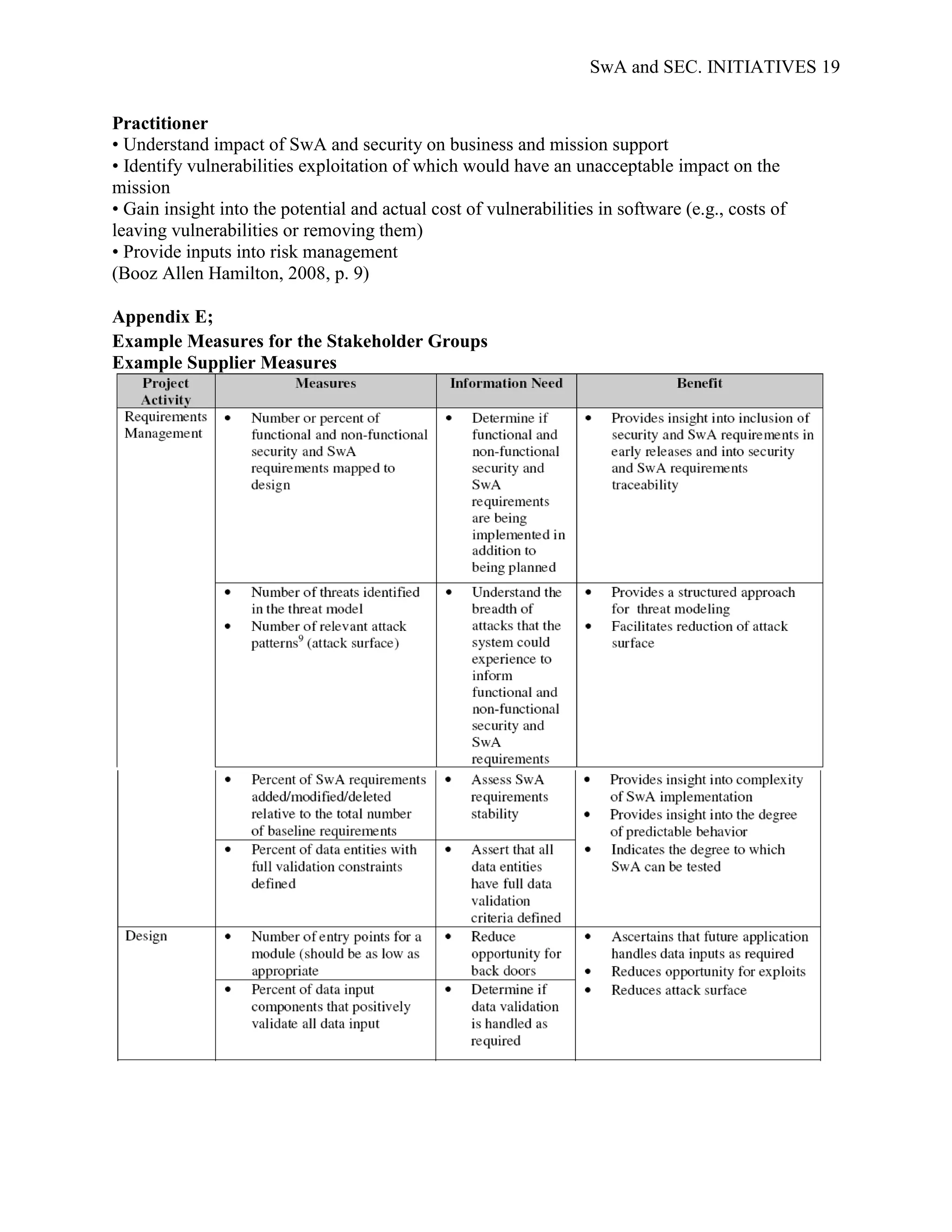

individuals with credential to access to the database containing the seeds used for initializing the

SecurID tokens. See Appendix L for a visual of the various stages of the ATP attack strategy on

RSA. Additionally, the algorithm used to generate the random number from the seed was also

compromised rendering the SecurID tokens vulnerable. Shortly after the RSA attack, "several

large defense contractors" (Diodati, 2011) were attacked and had confidential data removed from

their systems.

RSA utilized the latest in security technology enabling the company's Computer Incident

Response Team to detect and stop the attack quickly, but not quickly enough to stop the attackers

from obtaining confidential data. In RSA's case it was not a lack of technology but instead a lack

of policy on training employees to recognize threats and procedures for non-technical employees

to confirm or report those threats that lead to the data breach. A policy defining the amount of

training employees receive, what types of threats they should be trained to watch for, and ways

for non-technical employees to report suspicious e-mails could have prevented the initial attack.

The RSA case highlights the threats of outsourcing; a client and their operations are dependent

on the security measures of a security technology provider.

Developing, enforcing, and maintaining an applicable and robust security policy is vital

to security efforts of both government and private sectors. In response to increased security

needs and standards, government and private initiatives to support SwA have drastically

increased over the past few years. Numerous guidance programs, assessments, and standards

have been developed by both government and private sectors to address the issue of software

security assurance. Major government and private SwA initiatives are categorized and listed

under Appendix M; further elaboration on the listed initiatives is available at

[http://iac.dtic.mil/iatac/download/security.pdf]. Additionally, the MITRE Corporation, with](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/swaandsec-initiativeslandolfi-120621145709-phpapp01/75/US-Government-Software-Assurance-and-Security-Initiativesi-13-2048.jpg)

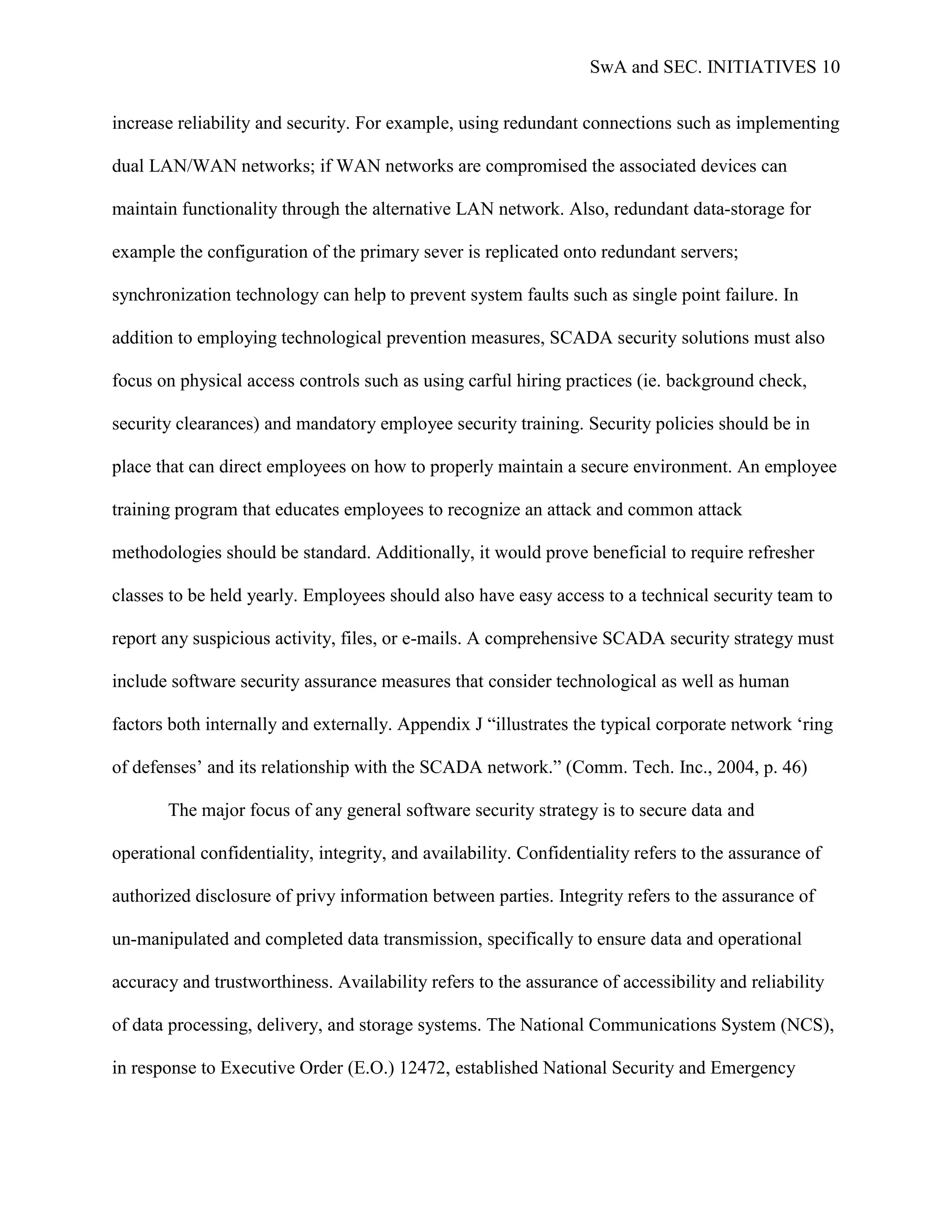

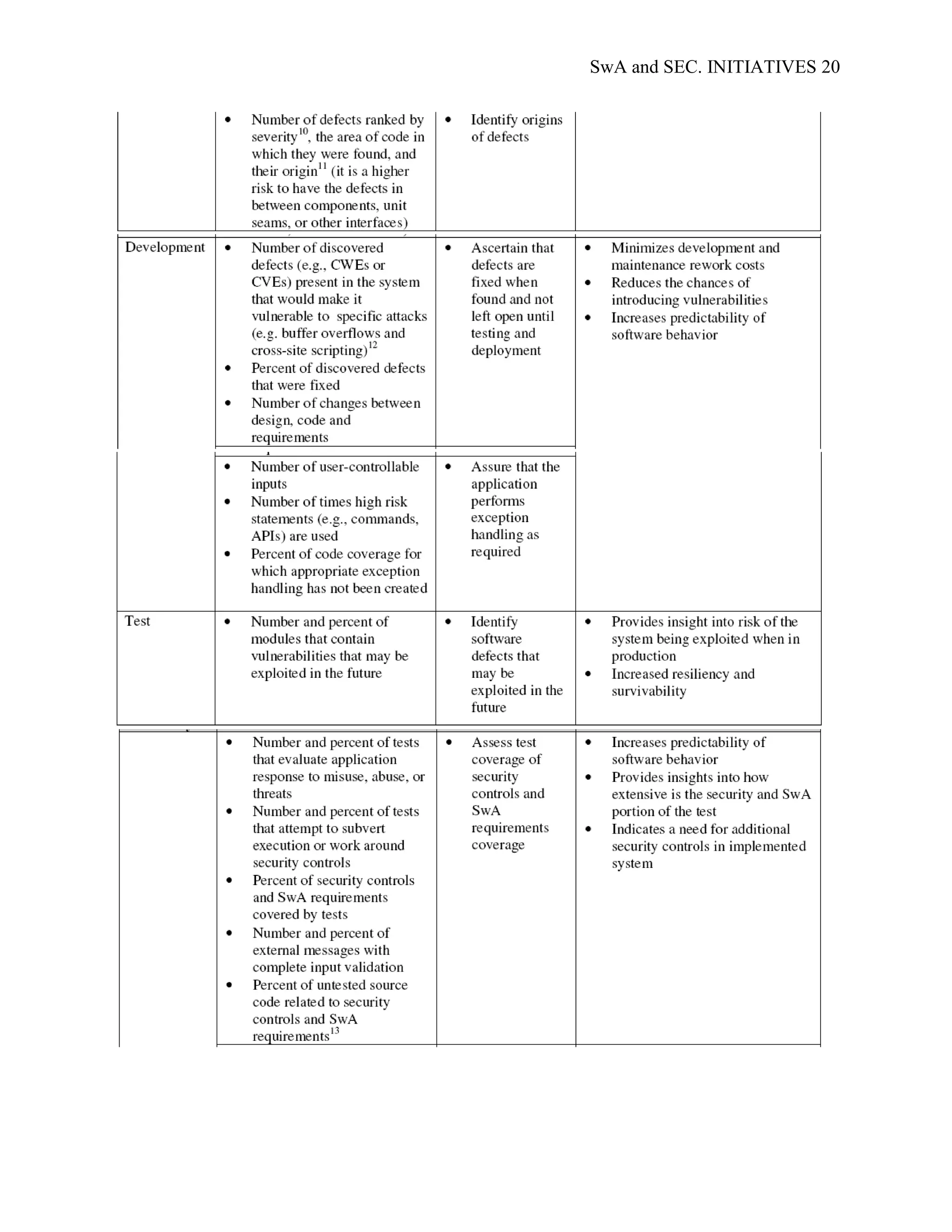

![SwA and SEC. INITIATIVES 14

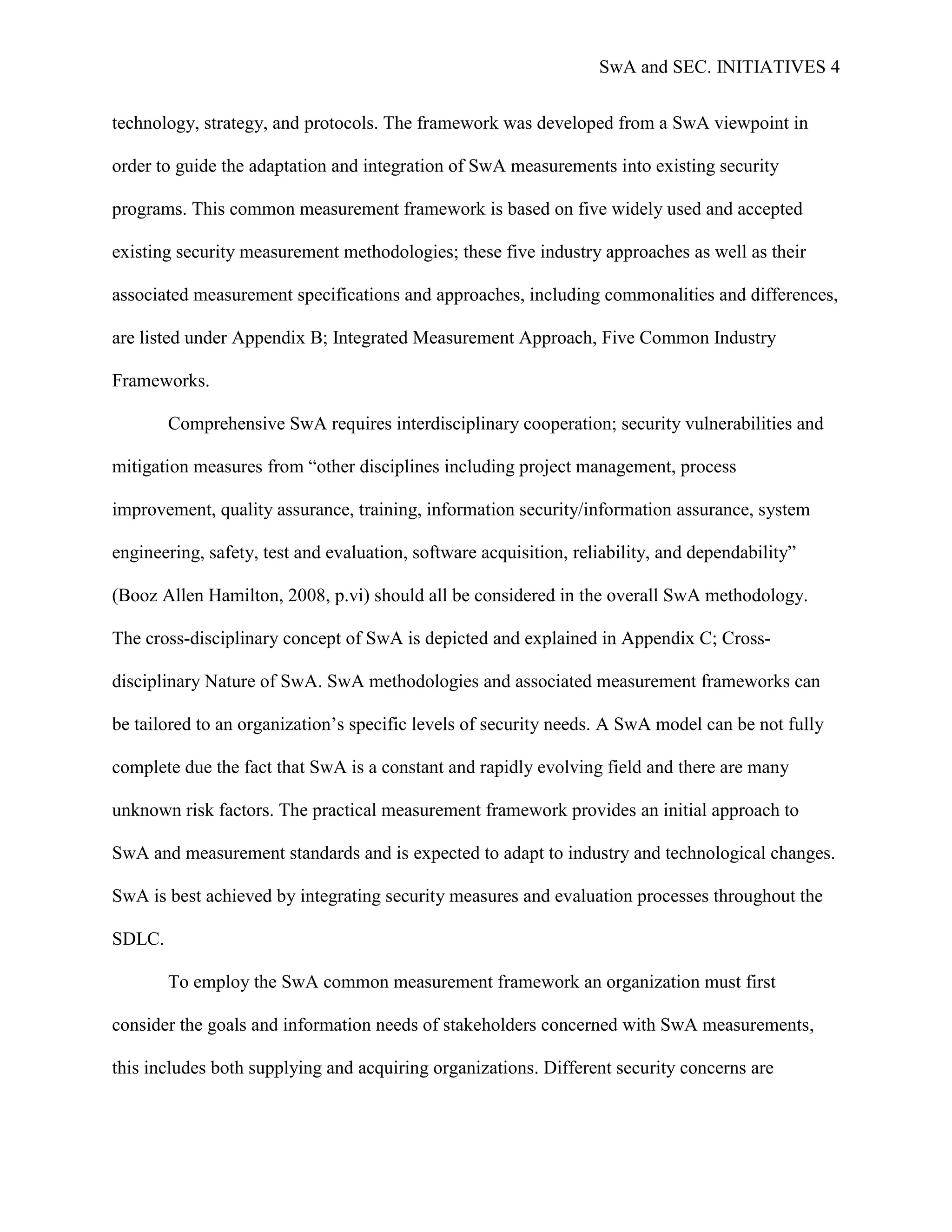

DHS sponsorship, complied a free collection of information security data standards and industry

security initiatives as a service for the secure cyber industry and community; the “Making

Security Measureable” is a living document and is available at

[http://measurablesecurity.mitre.org/list/index.html]. The document lists and elaborates on the

informational building blocks for developing and supporting SwA and security specifically

enumerations (standards), languages (encoding), repositories (storage), and security tools such as

assessment methodologies. No single building block can successfully prevent or mitigate attacks,

but when properly combined together into a comprehensive security plan used throughout the

SDLC they can efficiently support and defend SwA and security initiatives.

References:

Booz Allen Hamilton. (2008, October 1). Practical measurement framework for software

assurance and information security (N. Bartol, Ed.) (Version 1.0). Co-sponsored by

Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security, and National Institute of

Standards and Technology Software Assurance Measurement Working Group website:

https://buildsecurityin.us-cert.gov/swa/downloads/SwA_Measurement.pdf

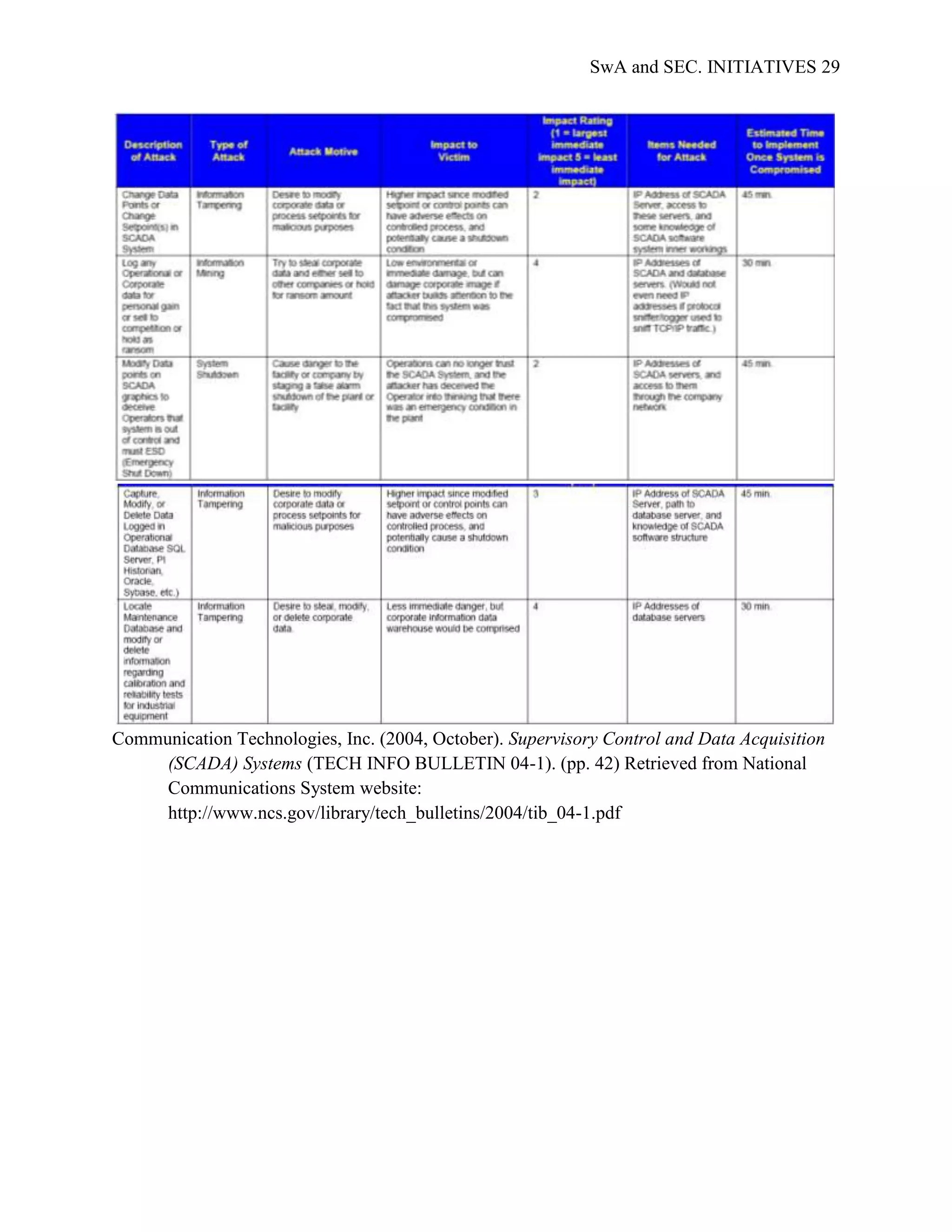

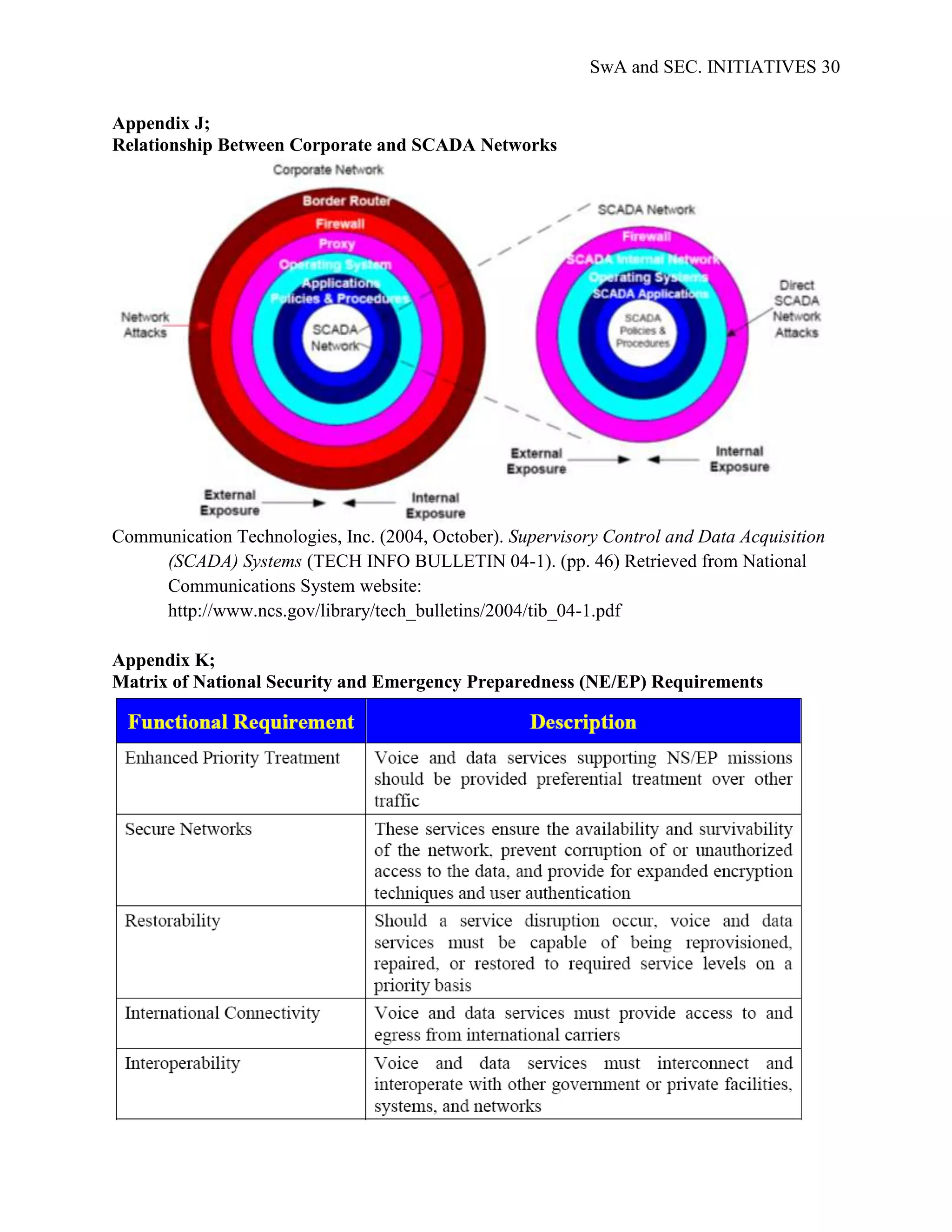

Communication Technologies, Inc. (2004, October). Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition

(SCADA) Systems (TECH INFO BULLETIN 04-1). Retrieved from National

Communications System website:

http://www.ncs.gov/library/tech_bulletins/2004/tib_04-1.pdf

Diodati, M. (2011, June 2). The seed and the damage done: RSA SecurID [Web log post].

Retrieved from Gartner: http://blogs.gartner.com/mark-diodati/2011/06/02/

the-seed-and-the-damage-done-rsa-securid/

Lewis, T. (2006). Critical infrastructure protection in homeland security: defending a

networked nation. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

RSA SecurID. (2011). Securing your future with two-factor authentication. Retrieved from EMC

Corporation website: http://www.rsa.com/node.aspx?id=1156](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/swaandsec-initiativeslandolfi-120621145709-phpapp01/75/US-Government-Software-Assurance-and-Security-Initiativesi-14-2048.jpg)

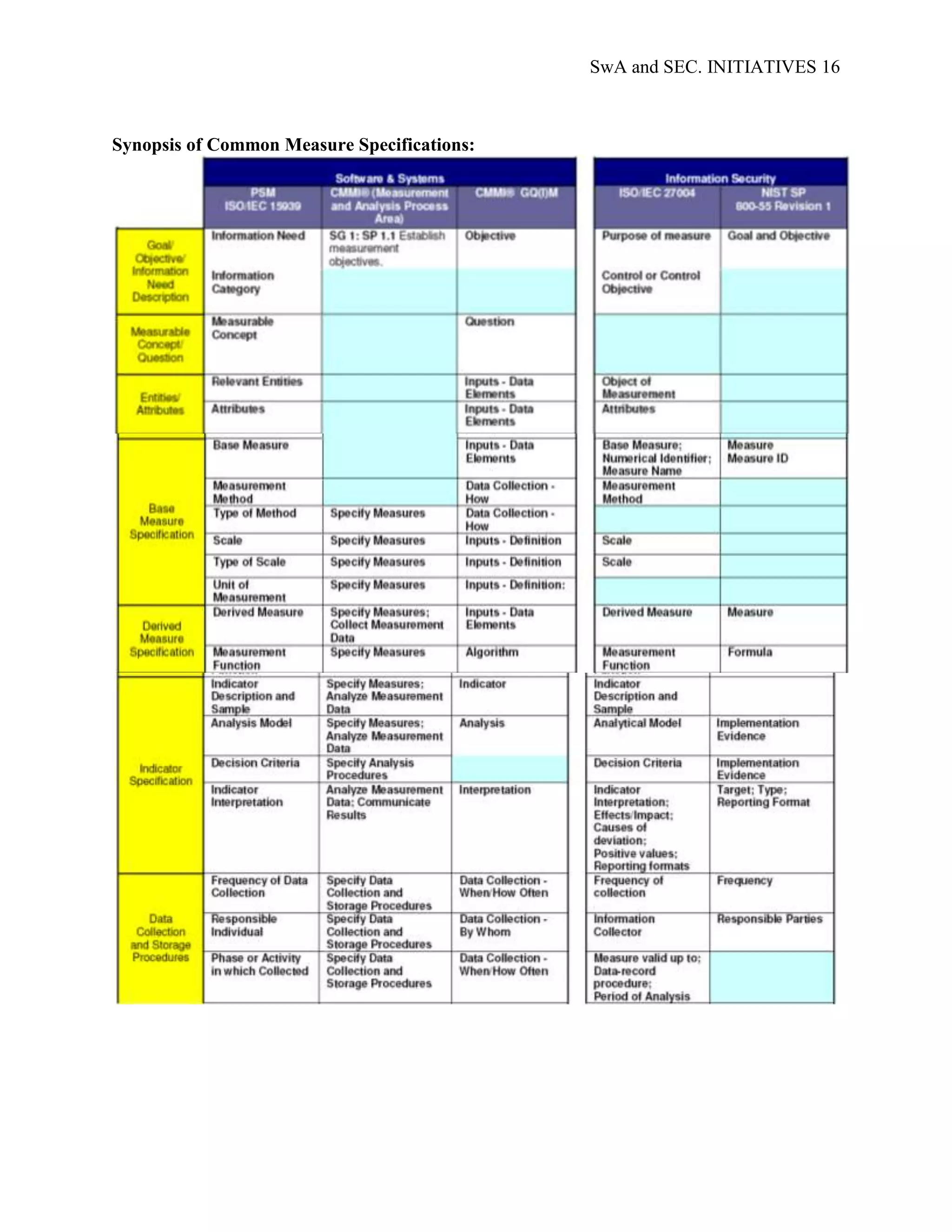

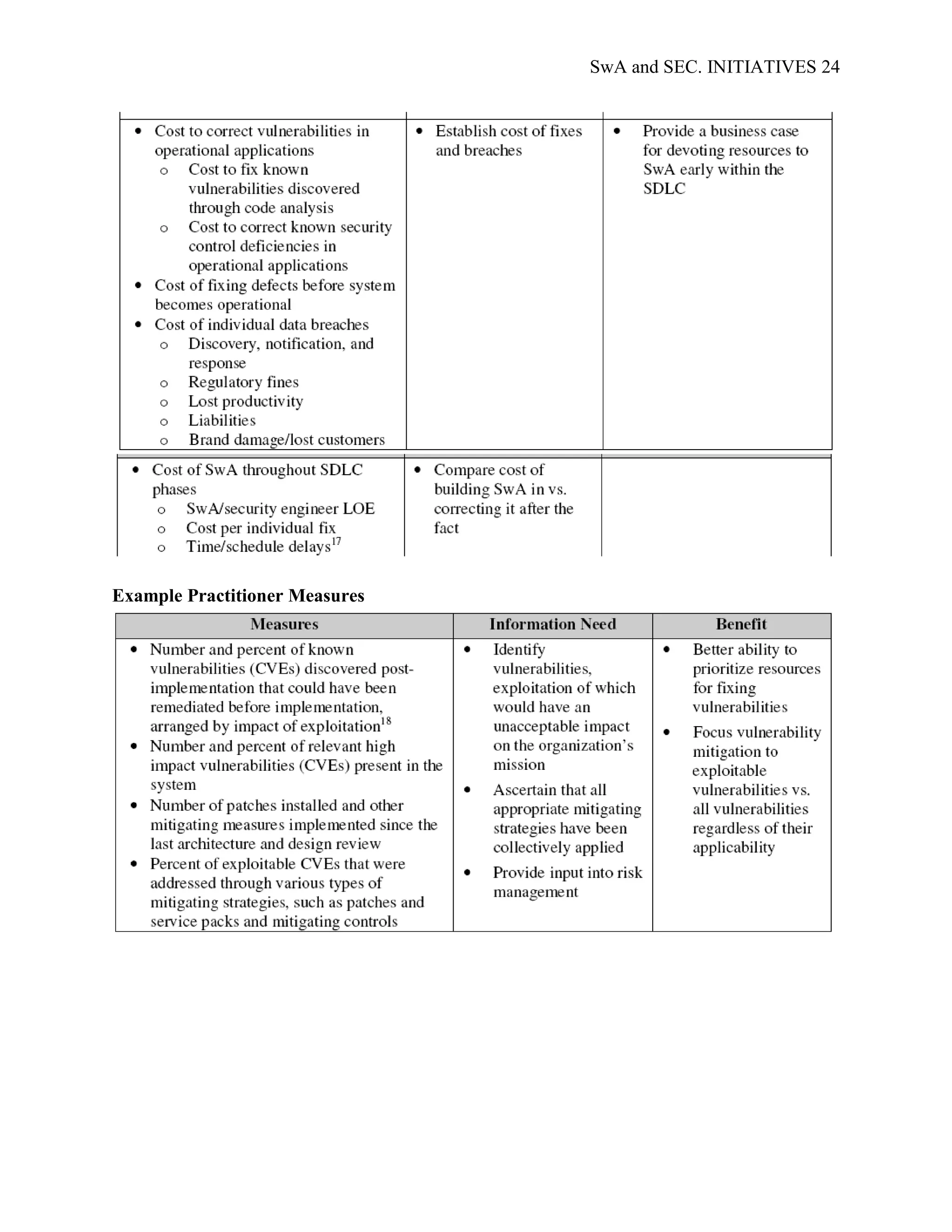

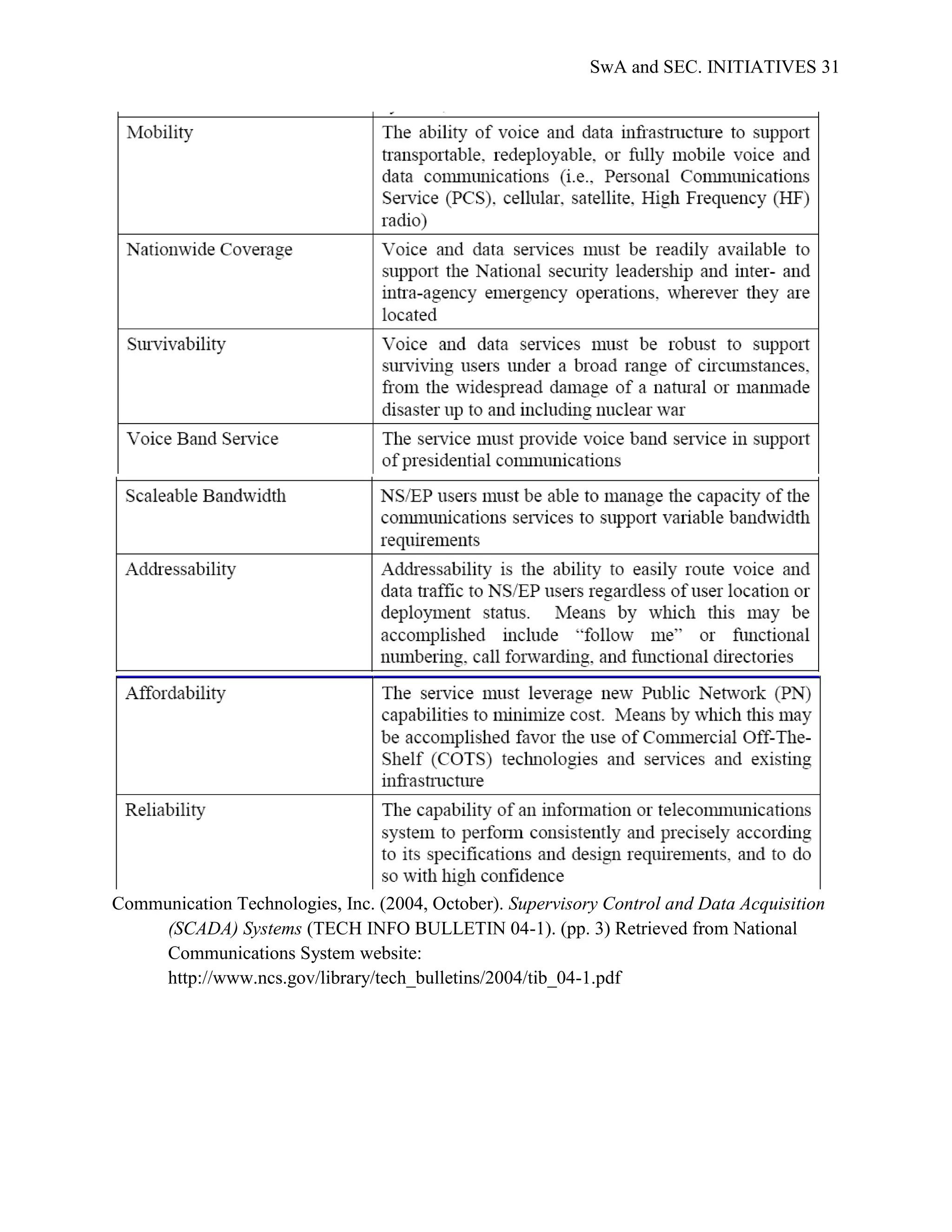

![SwA and SEC. INITIATIVES 32

Appendix L;

The Various Stages of the ATP Attack Strategy on RSA

Rivner, U. (2011, April 1). Anatomy of an attack [Web log post]. Retrieved from RSA:

http://blogs.rsa.com/rivner/anatomy-of-an-attack/

Appendix M;

Software Assurance Initiatives, Activities, and Organizations

US Government Initiatives

o DoD Software Assurance Initiative

Tiger Team Activities (participants; OUSD/AT&L, ASD/NII, NDIA,

AIA, GEIA, OMG)

o The National Security Agency (NSA) Center for Assured Software (CAS)

The Code Assessment Methodology Project (CAMP)

o DoD Anti-Tamper/Software Protection Initiative

o DSB Task Force on Mission Impact of Foreign Influence on DoD Software

o Global Information Grid (GIG) Lite

o NRL The Center for High Assurance Computing Systems (CHACS)

o DISA (CIAE) Application Security Project

o Other DoD Initiatives

DoDIIS Software Assurance Initiative (ESI-3A of DIA)

US Army CECOM Software Vulnerability Assessments and Malicious

Code Analyse

Air Force Application Security Pilot and Software Security Workshop

o DHS Software Assurance Program

Software Assurance Working Groups

Other Products and Activities (US-CERT BuildSecurityIn Portal, Software

Assurance Landscape)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/swaandsec-initiativeslandolfi-120621145709-phpapp01/75/US-Government-Software-Assurance-and-Security-Initiativesi-32-2048.jpg)