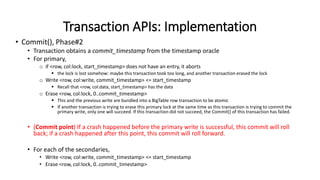

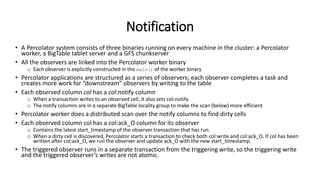

The document summarizes the paper on Google's Percolator, which details a system for large-scale incremental processing using distributed transactions. It describes how Percolator efficiently updates results by applying small independent changes instead of reprocessing entire repositories, addressing the limitations of existing systems like databases and MapReduce. Key components include a timestamp oracle for managing transactions and a notification mechanism for observing data changes, ensuring effective management of large datasets such as Google’s web search index.