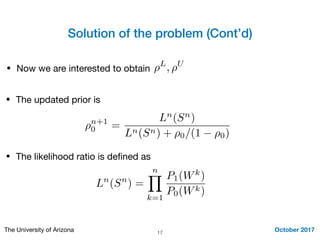

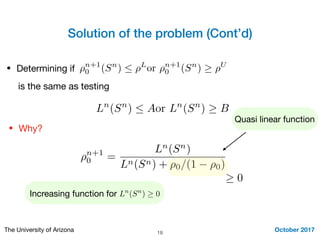

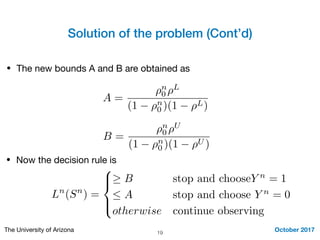

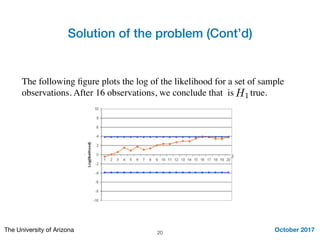

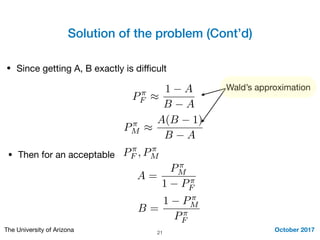

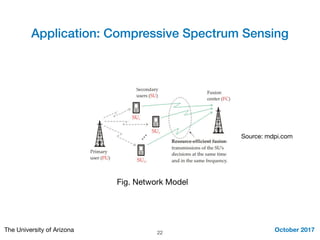

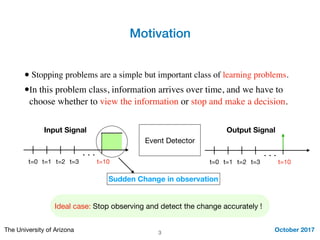

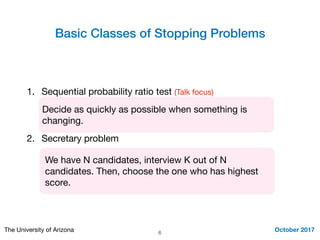

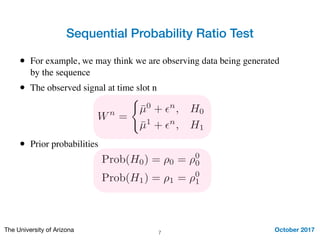

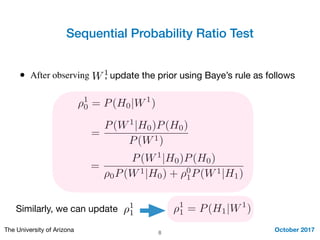

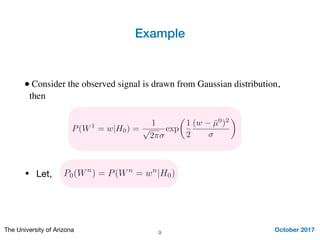

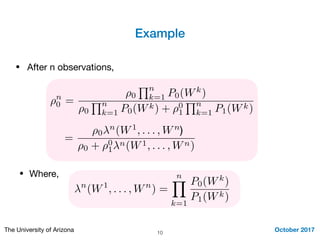

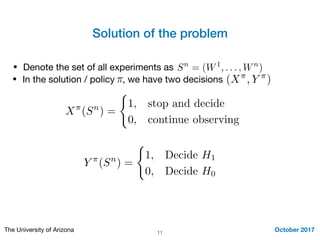

This document summarizes Mohamed Seif's work on stopping problems. It introduces stopping problems, which involve choosing when to stop collecting information and make a decision. It then provides preliminaries on hypothesis testing. The main focus is on the sequential probability ratio test, which sequentially updates probabilities based on likelihood ratios of observations. Thresholds are used to determine when to stop observing and make a decision. The sequential probability ratio test is applied to the problem of compressive spectrum sensing in wireless networks.

![Solution of the problem (Cont’d)

October 2017The University of Arizona 12

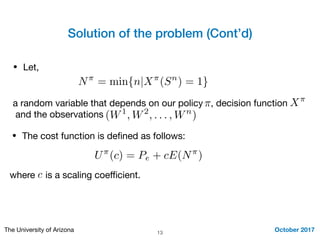

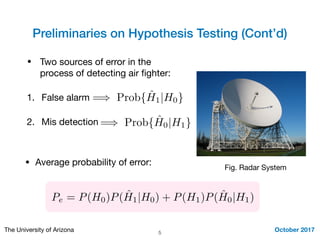

• Two sources of error can happen:

1. False alarm: stop and conclude H1

but the true is the null hypothesis H0

2. Mis detection: we did not pick up

any change, i.e., concludeH0 but

H1the alternative hypothesis is true

P⇡

F = E [Y ⇡

(Sn

|H0)]

P⇡

M = E [1 Y ⇡

(Sn

|H1)]

Pe = (1 ⇢0)P⇡

F + ⇢0P⇡

M

• Average probability of error:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/siework-171017203613/85/Stopping-Problems-12-320.jpg)