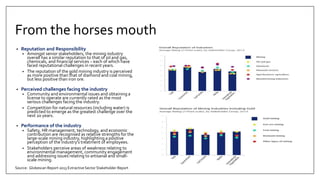

The document discusses the challenges that mining companies face in effectively engaging with stakeholders. It provides evidence that poor stakeholder relations have negatively impacted production at mines. Common mistakes made by companies include inadequate risk assessments, not involving stakeholders in engagement processes, and a lack of strategic engagement across the project lifecycle. Effective stakeholder engagement requires identifying the right stakeholders, choosing appropriate engagement activities, dedicating sufficient resources, and establishing clear rules of engagement. It also discusses considerations for including marginalized groups and handling opponents. Overall, the key message is that stakeholder engagement is complex and critical for mining project success but often done poorly.