The document discusses specification-based testing techniques, focusing on equivalence partitioning, boundary value analysis, decision tables, state transition testing, and use case testing. It explains how each technique aids in systematic test case design and identifies potential ambiguities and defects in specifications. The use of decision tables and state transition testing is highlighted for their effectiveness in handling complex business rules and finite state systems, respectively.

![Equivalence partitioning and boundary value

analysis

Equivalence partitioning (EP) is a good all-round specification-based black-bo

x technique. It can be applied at any level of testing and is often a good techniq

ue to use first. It is a common sense approach to testing, so much so that most

testers practise it informally even though they may not realize it. However, while

it is better to use the technique informally than not at all, it is much better to use

the technique in a formal way to attain the full benefits that it can deliver. This te

chnique will be found in most testing books, including [Myers, 1979] and [Copel

and, 2003].

The idea behind the technique is to divide (i.e. to partition) a set of test conditio

ns into groups or sets that can be considered the same (i.e. the system should

handle them equivalently), hence 'equivalence partitioning'. Equivalence partiti

ons are also known as equivalence classes – the two terms mean exactly the s

ame thing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/specificationbasedorblackboxtechniques-171202085802/75/Specification-based-or-black-box-techniques-3-2048.jpg)

![Decision table testing

Why use decision tables?

The techniques of equivalence partitioning and boundary value analysis are often

applied to specific situations or inputs. However, if different combinations of inputs result in d

ifferent actions being taken, this can be more difficult to show using equivalence partitioning

and boundary value analysis, which tend to be more focused on the user interface. The othe

r two specification-based techniques, decision tables and state transition testing are more fo

cused on business logic or business rules.

A decision table is a good way to deal with combinations of things (e.g. inputs).

This technique is sometimes also referred to as a 'cause-effect' table. The reason for this is t

hat there is an associated logic diagramming technique called 'cause-effect graphing' which

was sometimes used to help derive the decision table (Myers describes this as a combinator

ial logic network [Myers, 1979]). However, most people find it more useful just to use the tabl

e described in [Copeland, 2003].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/specificationbasedorblackboxtechniques-171202085802/75/Specification-based-or-black-box-techniques-5-2048.jpg)

![Decision table testing

Decision tables aid the systematic selection of effective test cases and can hav

e the beneficial side-effect of finding problems and ambiguities in the specificat

ion. It is a technique that works well in conjunction with equivalence partitionin

g. The combination of conditions explored may be combinations of equivalenc

e partitions.

In addition to decision tables, there are other techniques that deal wit

h testing combinations of things: pairwise testing and orthogonal arrays. These

are described in [Copeland, 2003]. Another source of techniques is [Pol et al.,

2001]. Decision tables and cause-effect graphing are described in [BS7925-2],

including designing tests and measuring coverage.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/specificationbasedorblackboxtechniques-171202085802/75/Specification-based-or-black-box-techniques-7-2048.jpg)

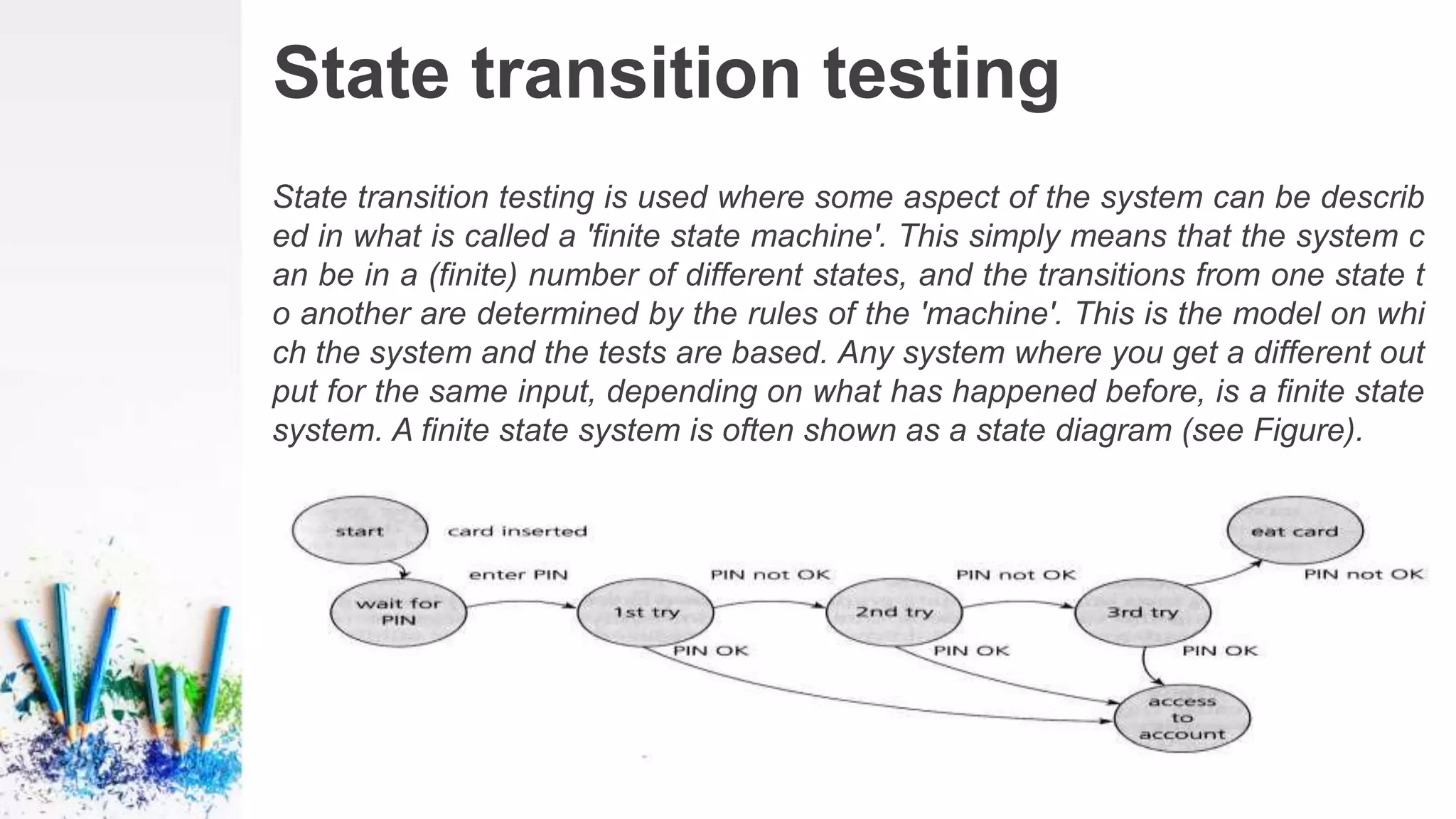

![State transition testing

Decision tables aid the systematic selection of effective test cases and can have

the beneficial side-effect of finding problems and ambiguities in the specification.

It is a technique that works well in conjunction with equivalence partitioning. The

combination of conditions explored may be combinations of equivalence partition

s.

In addition to decision tables, there are other techniques that deal with t

esting combinations of things: pairwise testing and orthogonal arrays. These are

described in [Copeland, 2003]. Another source of techniques is [Pol et al., 2001].

Decision tables and cause-effect graphing are described in [BS7925-2], including

designing tests and measuring coverage.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/specificationbasedorblackboxtechniques-171202085802/75/Specification-based-or-black-box-techniques-9-2048.jpg)

![Use case testing

Use case testing is a technique that helps us identify test cases that exercise the whole s

ystem on a transaction by transaction basis from start to finish. They are described by Iva

r Jacobson in his book Object-Oriented Software Engineering: A Use Case Driven Approa

ch [Jacobson, 1992].

A use case is a description of a particular use of the system by an actor (a use

r of the system). Each use case describes the interactions the actor has with the system i

n order to achieve a specific task (or, at least, produce something of value to the user). A

ctors are generally people but they may also be other systems. Use cases are a sequenc

e of steps that describe the interactions between the actor and the system.

Use cases are defined in terms of the actor, not the system, describing what th

e actor does and what the actor sees rather than what inputs the system expects and wh

at the system'outputs. They often use the language and terms of the business rather than

technical terms, especially when the actor is a business user. They serve as the foundatio

n for developing test cases mostly at the system and acceptance testing levels.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/specificationbasedorblackboxtechniques-171202085802/75/Specification-based-or-black-box-techniques-10-2048.jpg)