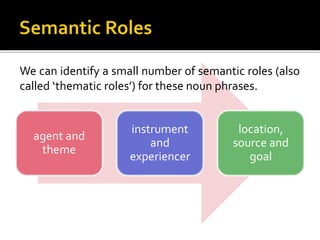

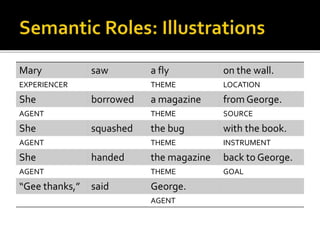

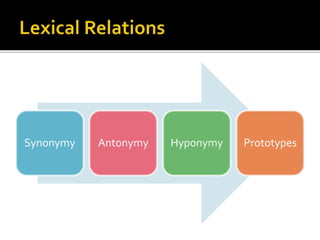

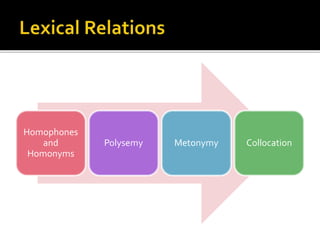

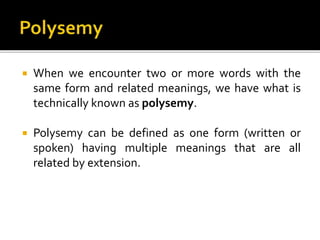

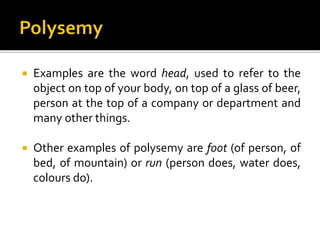

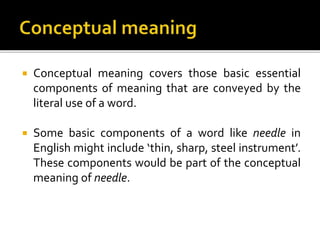

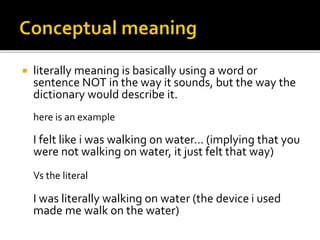

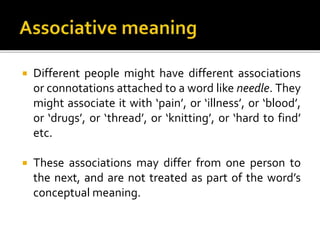

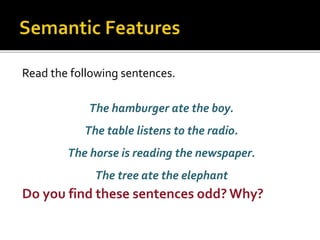

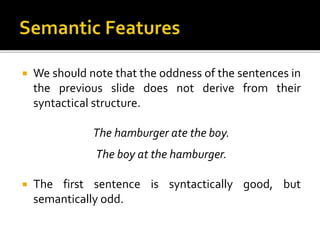

This document discusses various linguistic concepts related to semantics, or the study of meaning. It defines semantics and linguistic semantics, and explains how semantics analyzes meaning based on conventional definitions rather than subjective interpretations. It also discusses conceptual meaning, literal meaning, associative meanings, and how poets and authors play with meanings. Finally, it explores several semantic analysis approaches, including semantic features, semantic roles, and lexical relationships like synonymy, antonymy, and hyponymy.

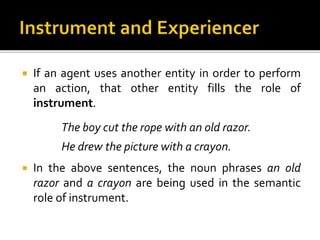

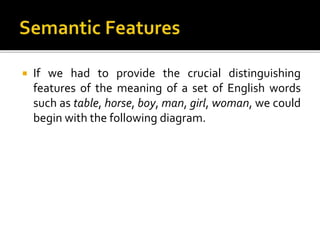

![ From a feature analysis like this, we can say that at

least part of the meaning of the word girl in English

involves the elements [+human, +female, -adult].

We can also characterize the feature that is crucially

required in a noun in order for it to appear as the

subject of a particular verb, supplementing the

syntactic analysis along with semantic features.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6809806-221122033026-1638f125/85/Semantics-ppt-18-320.jpg)

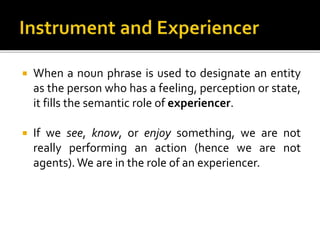

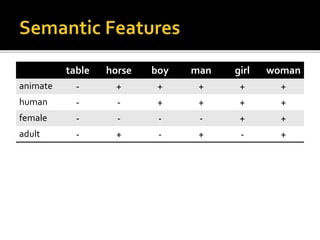

![The ___________________is reading the newspaper.

N [+ human]

This approach gives us the ability to predict which

nouns make this sentence semantically odd.

Some examples would be table, horse and

hamburger, because none of them have the required

feature [+ human].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6809806-221122033026-1638f125/85/Semantics-ppt-19-320.jpg)