This document discusses various topics related to learner language including:

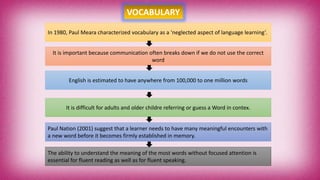

- The errors that second language learners make and what they reveal about the learner's language development.

- Contrastive analysis and error analysis frameworks for understanding learner errors.

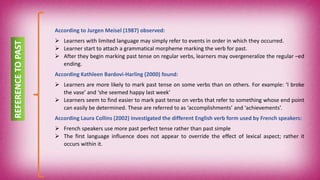

- Developmental sequences that all learners progress through regardless of their background.

- Stages of acquiring grammatical morphemes, negation, and questions.

- Influence of a learner's first language on acquiring features like possessive determiners, relative clauses, and verb tenses in the target language.