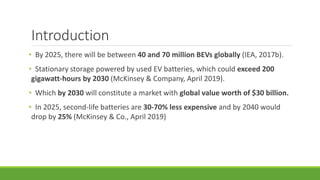

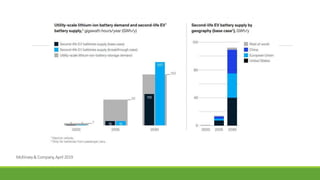

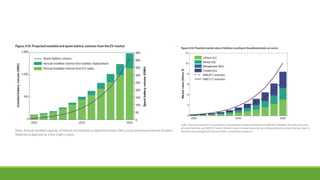

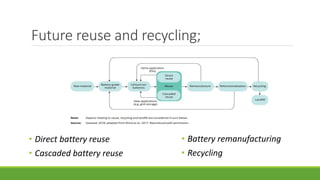

The document discusses the projected growth of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and the challenges associated with their end-of-life processes. It highlights the lack of standardization, immaturity of regulations, and the low current rates of recycling and reuse. Future trends indicate a significant increase in end-of-life vehicles by 2027, alongside a predicted demand for battery materials which can be met through recycling initiatives.