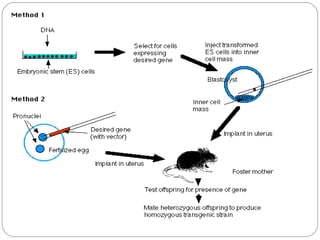

The document provides an overview of animal models in laboratory settings, detailing their definitions, classifications, and applications in biological and medical research. It elaborates on different types of models such as exploratory, explanatory, and predictive, along with specific classifications like induced, spontaneous, transgenic, negative, and orphan disease models. Additionally, it discusses the implications of fidelity and extrapolation in research and the importance of model selection to ensure relevant and translatable results.