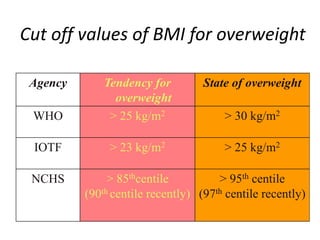

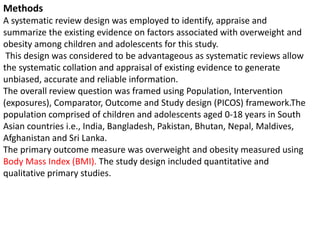

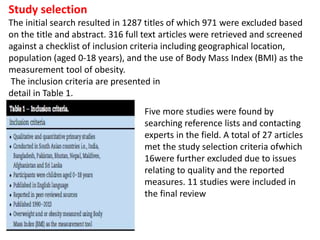

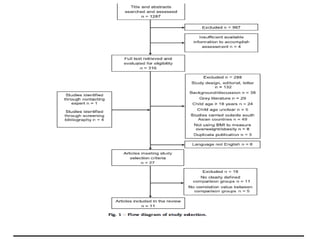

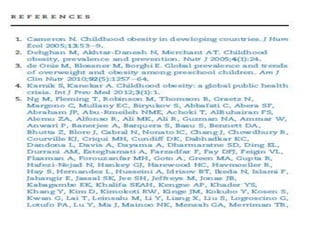

This document summarizes a systematic review of factors associated with childhood overweight and obesity in South Asian countries. The review included 11 studies from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka that used BMI to measure overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. The studies found wide variation in overweight prevalence from 3.1-19.7% and obesity prevalence from 1.2-14.5%. Lack of physical activity was associated with overweight/obesity in most studies, while higher socioeconomic status, urban residence, and consumption of junk food/fast food were also identified as risk factors.