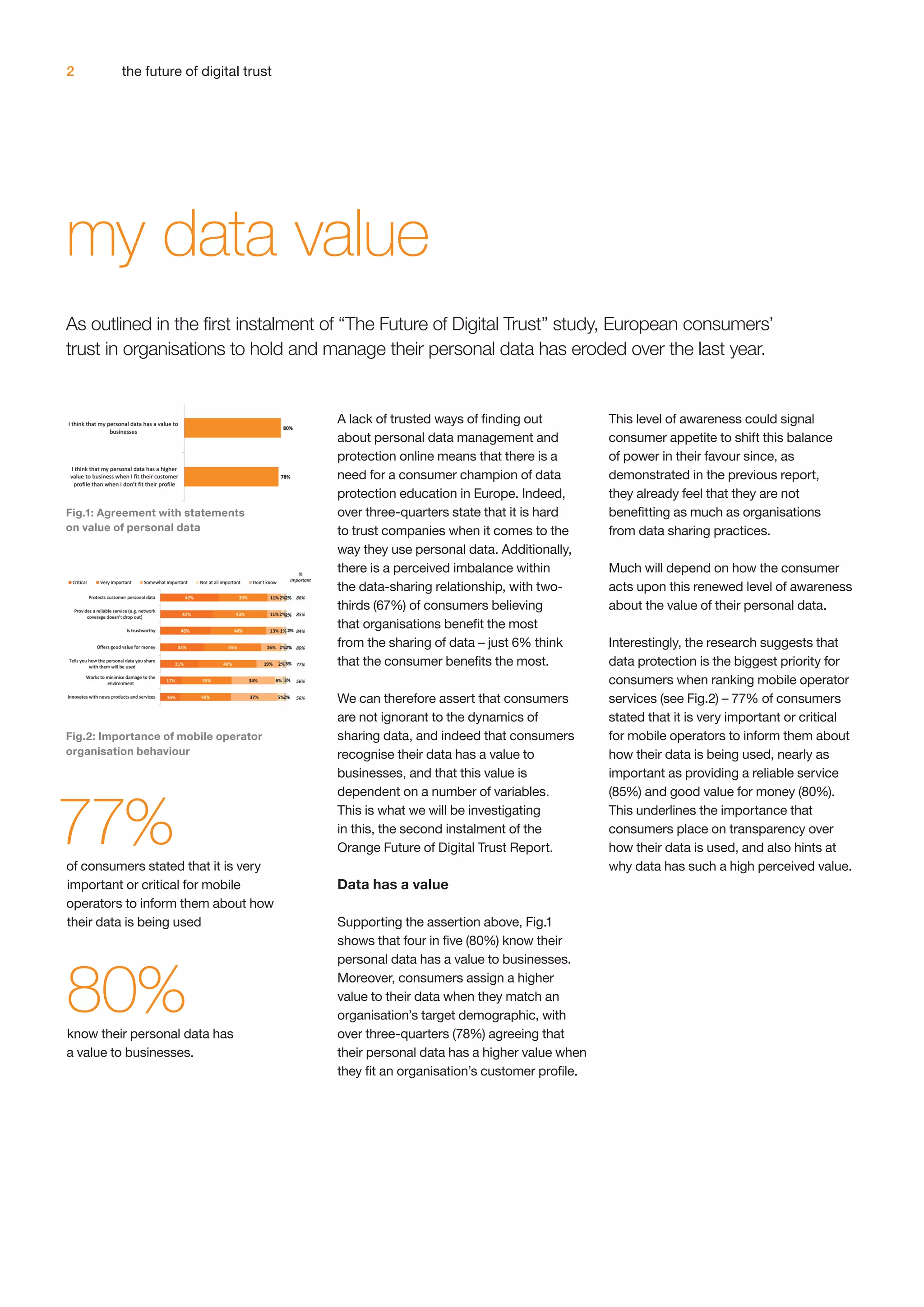

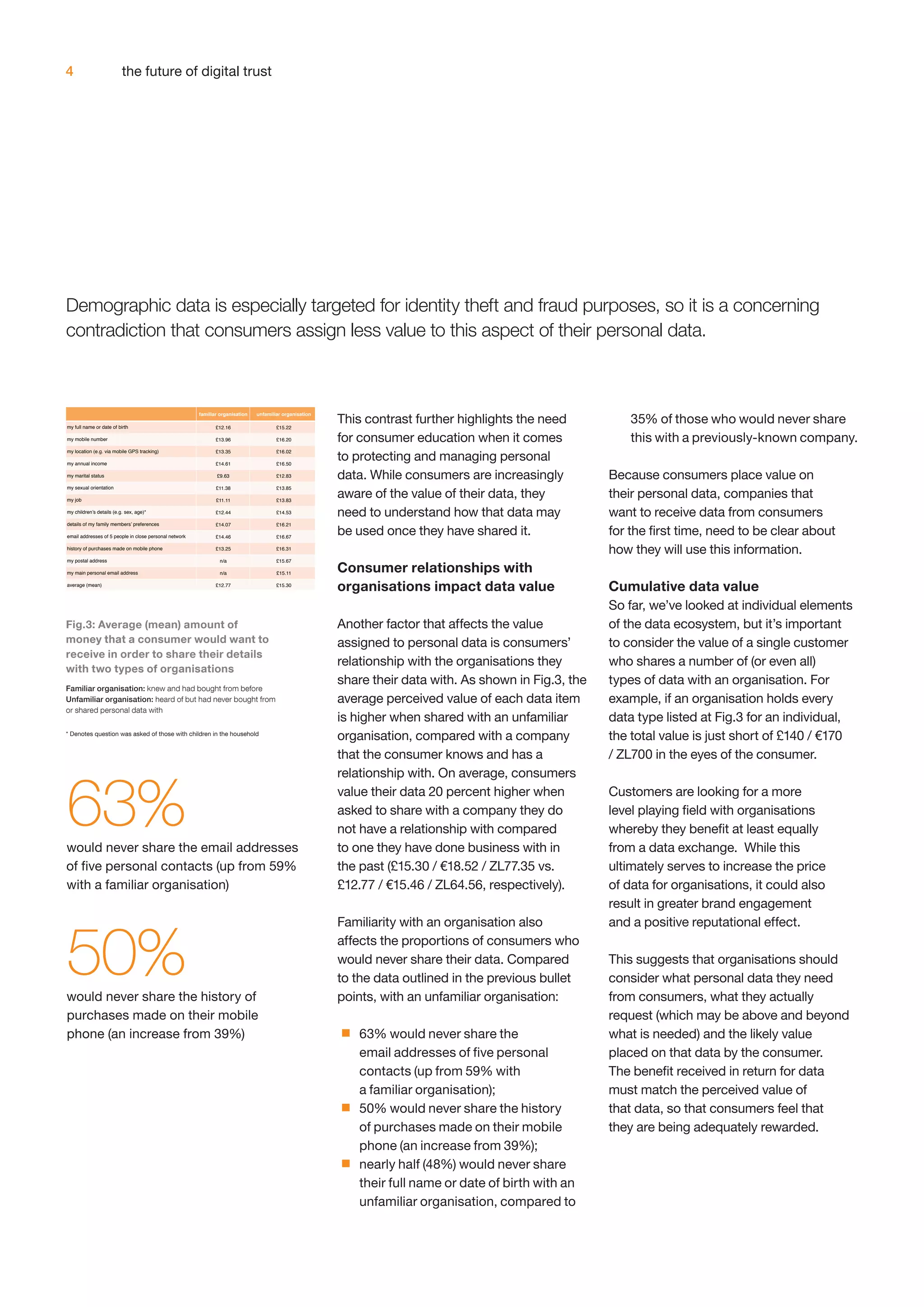

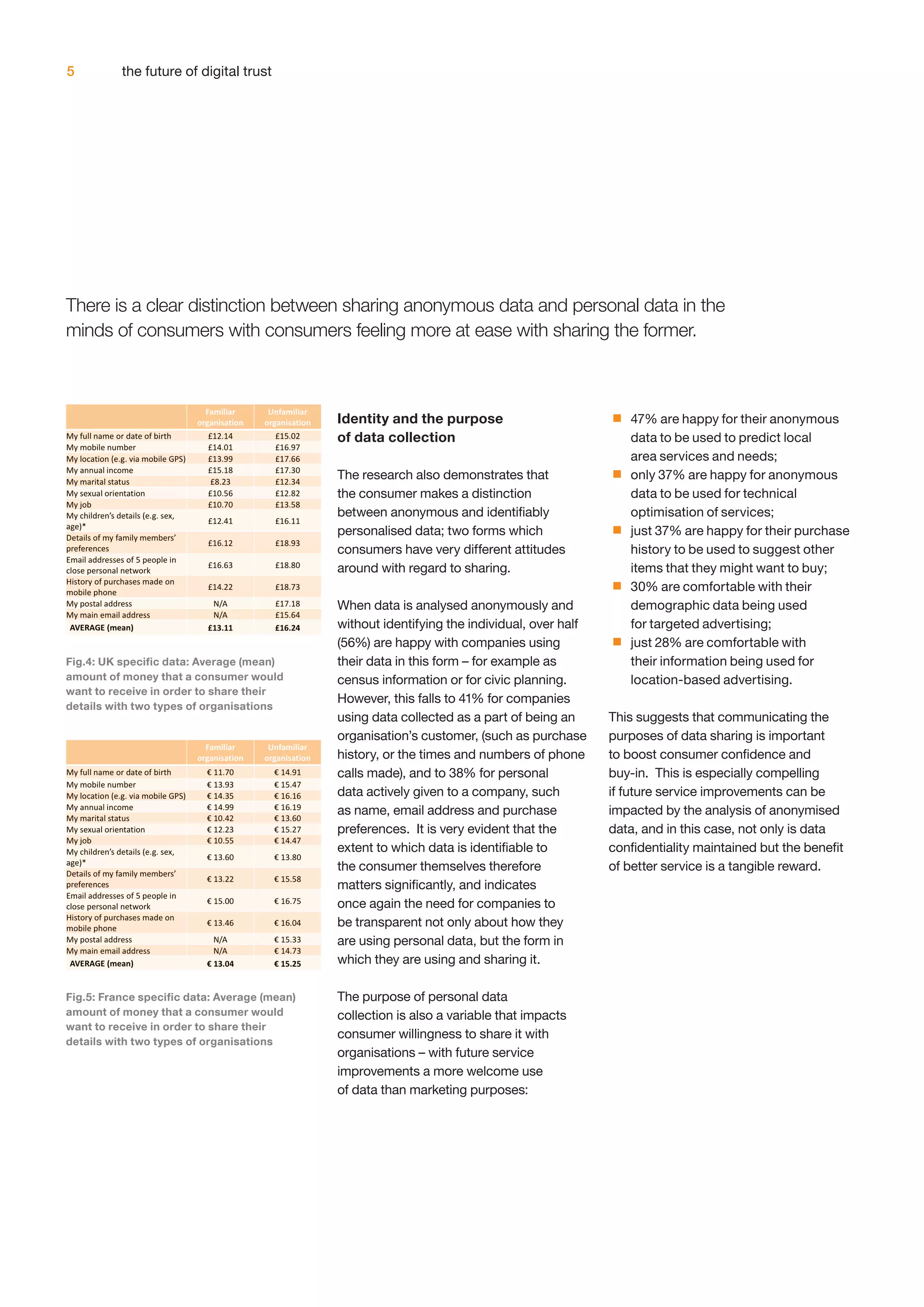

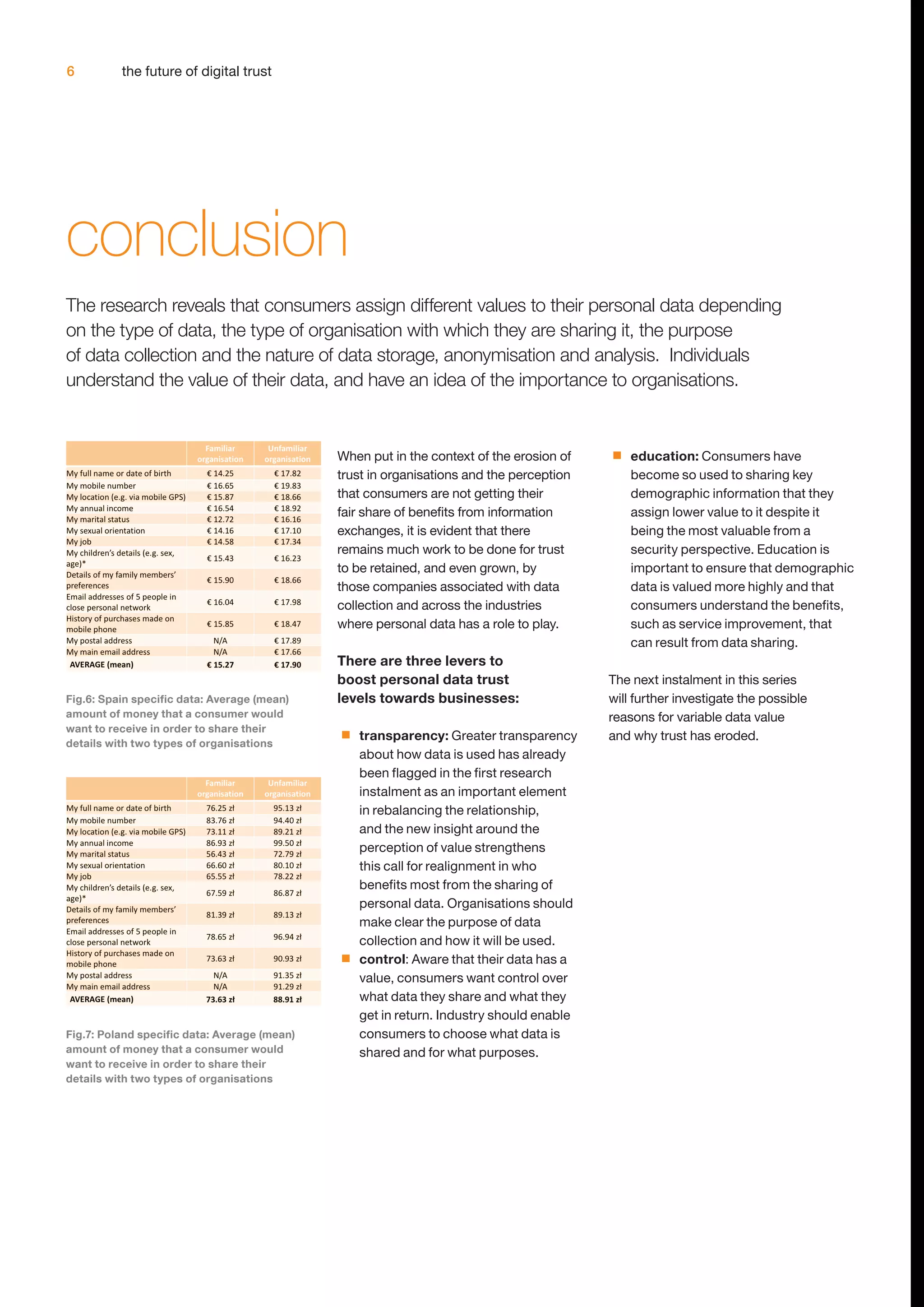

The study reveals that consumer trust in organizations managing personal data has significantly declined, with 75% finding it hard to trust companies regarding data use. While consumers recognize the value of their personal data, their willingness to share it varies based on the type of data and their relationship with the organization, indicating a desire for transparency, control, and education on data management. The findings stress the need for organizations to be transparent about data use and to align the perceived value of data with consumer benefits to rebuild trust.