- The document examines flaws in the experimental design and methodology of the paper "Debunking the Myths of Influence Maximization: A Benchmarking Study".

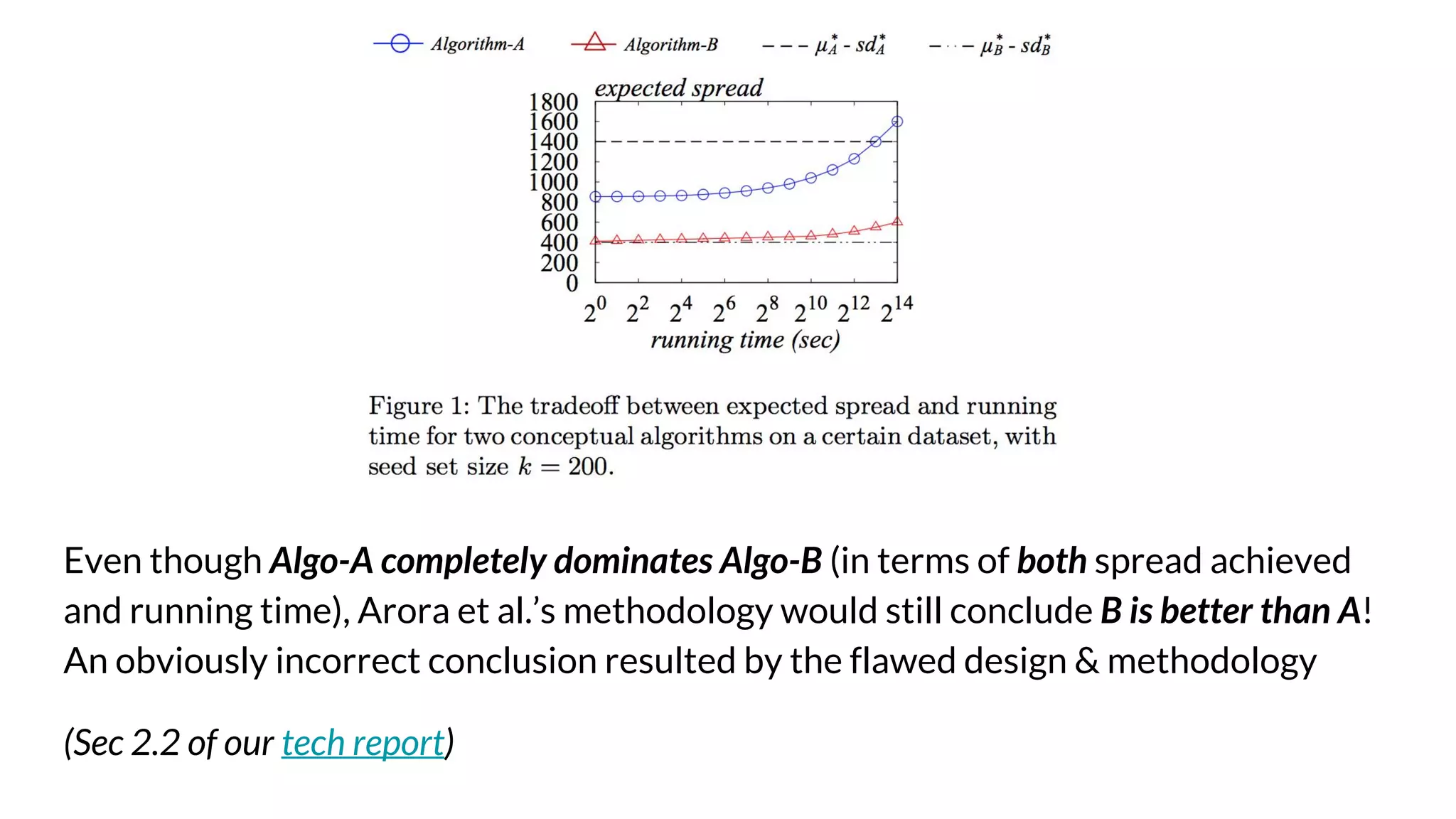

- It identifies fundamental flaws that lead to incorrect conclusions, such as algorithms being held to different standards of optimality.

- It also finds unreproducible and critical experiments used to determine benchmarking parameters, and refutes over 10 misclaims made about previous influence maximization algorithms.

![Background & Overview

● “Debunking the Myths of Influence Maximization: A Benchmarking Study” [1] is a

SIGMOD 2017 paper by Arora, Galhotra, and Ranu. That paper:

○ undertakes a benchmarking performance study on the problem of Influence

Maximization

○ claims to unearth and debunks many “myths” around Influence Maximization

research over the years

● Our article (https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.05144 ):

○ examines fundamental flaws of their experimental design & methodology

○ points out unreproducible result in critical experiments

○ refutes 11 mis-claims in [1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-2-2048.jpg)

![Our goals and contributions

● Objectively, critically, and thoroughly review Arora et al. [1]

● Identify fundamental flaws in [1]’s experimental design/methodology, which:

○ fails to understand the trade-off between efficiency and solution quality

○ when generalized, leads to obviously incorrect conclusions such as the

Chebyshev’s inequality is better than Chernoff bound

● Identify unreproducible, but critical experiments which are used to determine

benchmarking parameters. By design, this has serious implications of the

correctness of all experiments in Arora et al. [1]

● Refute 11 mis-claims by Arora et al. [1] on previously published papers,

including then state-of-the-art approximation algorithms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-3-2048.jpg)

![Flawed Design & Methodology

● Arora et al.’s design question: “How long does it take for each algorithm to

reach its ‘near-optimal’ empirical accuracy”

● Their experimental design/methodology is:

○ For each influence maximization Algorithm-A,

○ Identify a parameter p that controls the trade-off between running time and spread

achieved.

○ Choose value p* for the parameter, such that in a given “reasonable time limit” T (not

defined in [1]), Algorithm-A can achieve its best spread.

○ Compare all algorithms’ running time at their each individual p*.

● This is a flawed methodology that will lead to scientifically incorrect results (see

next few slides)

(Sec 2.2 of our tech report)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-6-2048.jpg)

![Misclaims related to IMM algorithm [3]

and TIM+ algorithm [2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-12-2048.jpg)

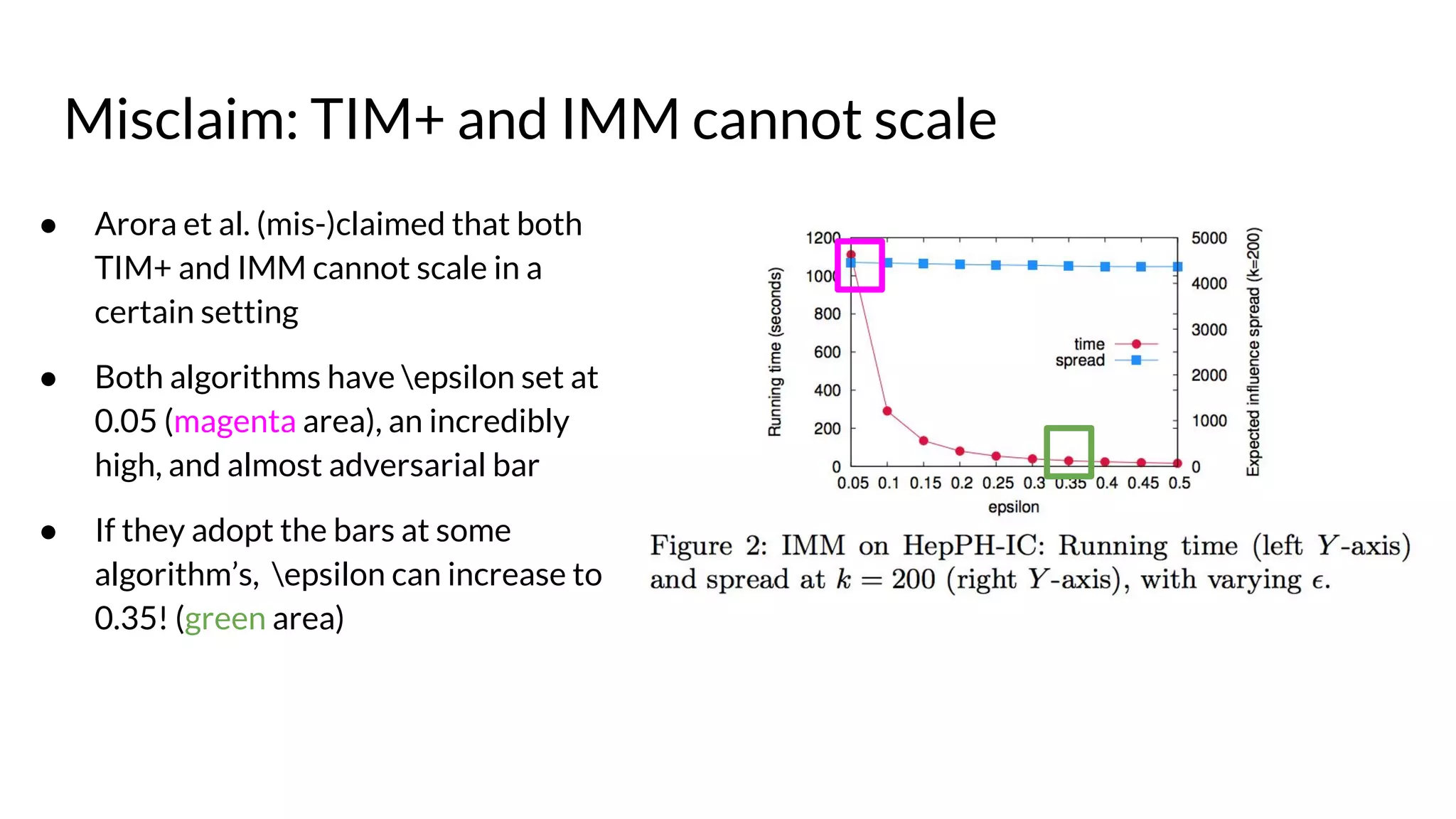

![TIM+ and IMM algorithms

● Both are fast and highly scalable (1-1/e-epsilon)-approximation algorithms

○ Underlying methodology: Sampling reverse-reachable set for seed selection

● IMM improves upon TIM+ by using martingale theory to draw much fewer

samples, for any given epsilon (i.e., same worst-case performance guarantee)

● Both papers [2][3] showed that very small epsilon (< 0.1) increases running time

a lot but does not further improve quality too much (i.e., the trade-off at that

point isn’t worth it)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-13-2048.jpg)

![● Running time (left Y-axis) sharply

decreases as epsilon goes up.

● Solution quality (right Y-axis) is

only marginally affected.

● E.g., epsilon at 0.05 vs. 0.5, the

running time difference is 68x, but

accuracy difference is only 2.1%.

● Quite similar trend for TIM+

● See original papers [2][3] for

details.

Efficiency & quality tradeoff for IMM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-14-2048.jpg)

![Misclaims related to SimPath [4]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-17-2048.jpg)

![Mis-claims based on infinite loops

● Arora et al [1] stated that the SimPath algorithm [4] fails to finish on two

datasets after 2400 hours (100 days), using code released by authors of [4].

● Our attempts to reproduce found that SimPath finishes within 8.6 and 667

minutes respectively on those two datasets (UBC server)

○ 8.6 minutes = 0.006% of 2400 hours

○ 667 minutes = 0.463% of 2400 hours

● Reasons for discrepancies: Arora et al. [1] failed to preprocess datasets

correctly as per the source code released by [4], and ran into infinite loops and

got stuck for 100 days

(Sec 3.2 of our tech report)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-18-2048.jpg)

![More mis-claims on SimPath

● Misclaim: LDAG [5] is better than SimPath on “LT-uniform” model

● Refutation: The two datasets where Arora et al. stuck in infinite loops happen

to be prepared according to “LT-uniform” model. This is a corollary of the

previous misclaim

● Misclaim: LDAG is overall better than SimPath

● Refutation: This is a blanket statement contradicting experimental results:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-19-2048.jpg)

![“EaSyIM [6] is one of the best IM algorithm”

● Arora et al. recommends that EaSyIM heuristic [6] as one of the best IM

algorithms, comparable to IMM and TIM+

○ EaSyIM [6] and this SIGMOD paper [1] share two co-authors: Arora, Galhotra

● However, their own Table 3 (see below) illustrates EaSyIM is not scalable at all,

providing a refutation to this misleading claim

○ In both WC and LT settings, EaSyIM failed to finish on 3 largest datasets after 40 hours, while

IMM and TIM finished on all datasets. In IC setting, it failed on 2 largest datasets](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-21-2048.jpg)

![“EaSyIM is Most Memory-Efficient”

● Misclaim: EaSyIM [6] is the “most-memory efficient” algorithm

● Their justification: EaSyIM only stores a scalar-value per each node in graph

● Refutation: A meaningless statement that ignores the trade-off between

memory consumption and quality of solution:

○ E.g., many more advanced algorithms such as IMM [3] and TIM+ [2] utilizes more

memory to achieve better solutions

○ The same “one scalar per node” argument can be used for arguing that a naive algorithm that

randomly select k seeds is the most memory efficient, but is this useful at all?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-22-2048.jpg)

![Conclusions and Key Takeaways

● Our technical report critically reviews the SIGMOD benchmarking paper by

Arora et al. [1], claiming to debunk “myths” of influence maximization research

● We found that Arora et al. [1] is riddled with problematic issues, including:

○ ill-designed and flawed experimental methodology

○ unreproducible results in critical experiments

○ more than 10 mis-claims on a variety of previously published algorithms

○ misleading conclusions in support of an unscalable heuristic (EaSyIM)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-23-2048.jpg)

![References

[1]. A. Arora, S. Galhotra, and S. Ranu. Debunking the myths of influence maximization: An in-depth

benchmarking study. In SIGMOD 2017.

[2]. Y. Tang, X. Xiao, and Y. Shi. Influence maximization: near-optimal time complexity meets practical

efficiency. In SIGMOD, pages 75–86, 2014.

[3]. Y. Tang, Y. Shi, and X. Xiao. Influence maximization in near-linear time: a martingale approach. In

SIGMOD, pages 1539–1554, 2015.

[4]. A. Goyal, W. Lu, and L. V. S. Lakshmanan. SimPath: An efficient algorithm for influence maximization

under the linear threshold model. In ICDM, pages 211–220, 2011.

[5]. W. Chen, Y. Yuan, and L. Zhang. Scalable influence maximization in social networks under the linear

threshold model. In ICDM, pages 88–97, 2010.

[6]. S. Galhotra, A. Arora, and S. Roy. Holistic influence maximization: Combining scalability and efficiency

with opinion-aware models. In SIGMOD, pages 743–758, 2016.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/refutations-170523045334/75/Refutations-on-Debunking-the-Myths-of-Influence-Maximization-An-In-Depth-Benchmarking-Study-24-2048.jpg)