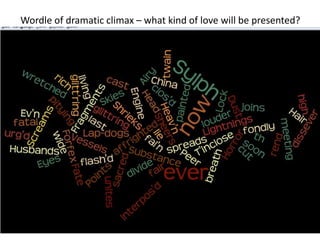

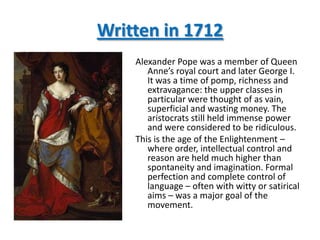

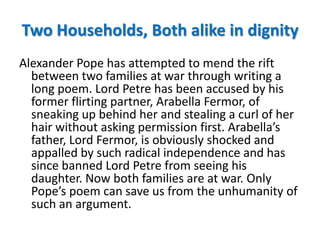

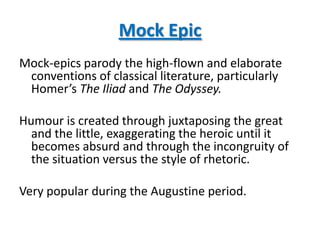

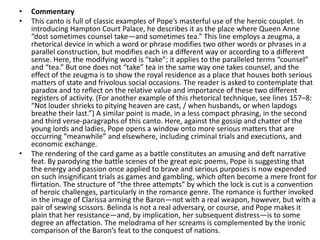

This passage summarizes key elements of Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock, including its use of mock-epic conventions to satirize trivial aspects of aristocratic society. Pope employs techniques like zeugmas to highlight contradictions between serious matters of state and frivolous social occasions. The card game is portrayed as a heroic battle, parodying epic poems and suggesting passion once used for serious purposes is now wasted on insignificant games. Belinda's distress is implied to be somewhat affected as well.