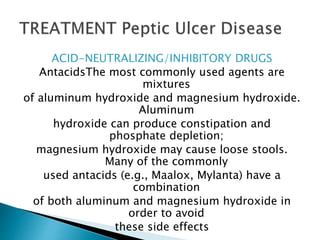

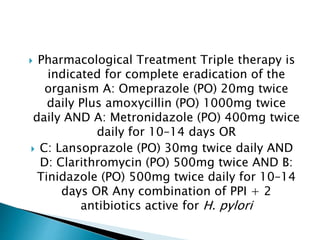

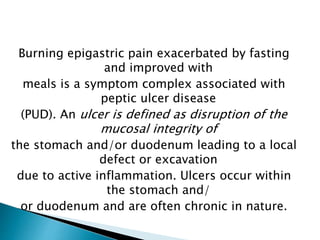

This document discusses peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori infection. It begins by describing the symptoms of peptic ulcer disease and defining ulcers. It then discusses the defenses of the gastric mucosa and factors that can overcome these defenses, leading to ulcer formation. A major section is devoted to describing the pathogenesis of H. pylori infection and how it interacts with host factors to sometimes cause peptic ulcers or gastric cancer. The diagnostic evaluation and treatment of peptic ulcers and H. pylori are also covered.

![PathophysiologyH. pylori infection is virtually

always associated with

a chronic active gastritis, but only 10–15% of

infected individuals

develop frank peptic ulceration. The

pathophysiology of ulcers not associated with

H. pylori or

NSAID ingestion (or the rare Zollinger-Ellison

syndrome [ZES]) is

becoming more relevant as the incidence of H.

pylori is dropping,

particularly in the Western world](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pud-200530211007/85/Pud-11-320.jpg)

![Several biopsy urease

tests have been developed (PyloriTek,

CLOtest, Hpfast, Pronto Dry) that have

a sensitivity and specificity of >90–95%. Several

noninvasive methods for detecting

this organism have been developed.

Three types of studies routinely usedinclude serologic

testing, the 13C- or 14C-urea breath test, and the fecal

H. pylori (Hp) antigen test. Occasionally, specialized

testing such as serum gastrin and gastric

acid analysis or sham feeding may be needed in

individuals with complicated

or refractory PUD (see “Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome [ZES],”

below). Screening for aspirin or NSAIDs (blood or urine)

may also be

necessary in refractory H. pylori–negative PUD patients.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pud-200530211007/85/Pud-23-320.jpg)