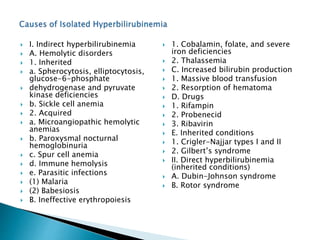

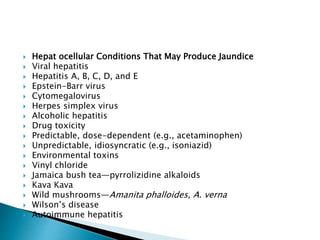

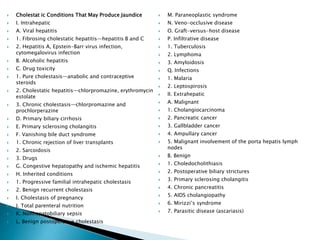

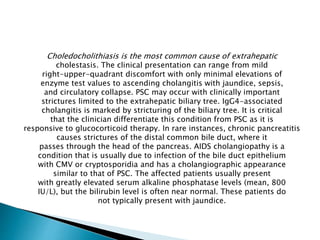

This document summarizes jaundice and hyperbilirubinemia. It describes how jaundice results from the deposition of bilirubin in tissues due to high bilirubin levels in the blood. Bilirubin levels can be estimated by examining the skin and mucous membranes for a yellow color. Higher bilirubin levels result in darker urine. The document then discusses the production, metabolism, and excretion of bilirubin, how liver disease or other issues can cause hyperbilirubinemia, and how to evaluate patients with jaundice.

![Laboratory Tests A battery of tests are helpful in the

initial evaluation

of a patient with unexplained jaundice. These include

total and

direct serum bilirubin measurement with fractionation;

determination

of serum aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and

albumin

concentrations; and prothrombin time tests. Enzyme

tests (alanine

aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase

[AST], and

alkaline phosphatase [ALP]) are helpful in

differentiating between

a hepatocellular process and a cholestatic processA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jaundice-200530210420/85/Jaundice-23-320.jpg)