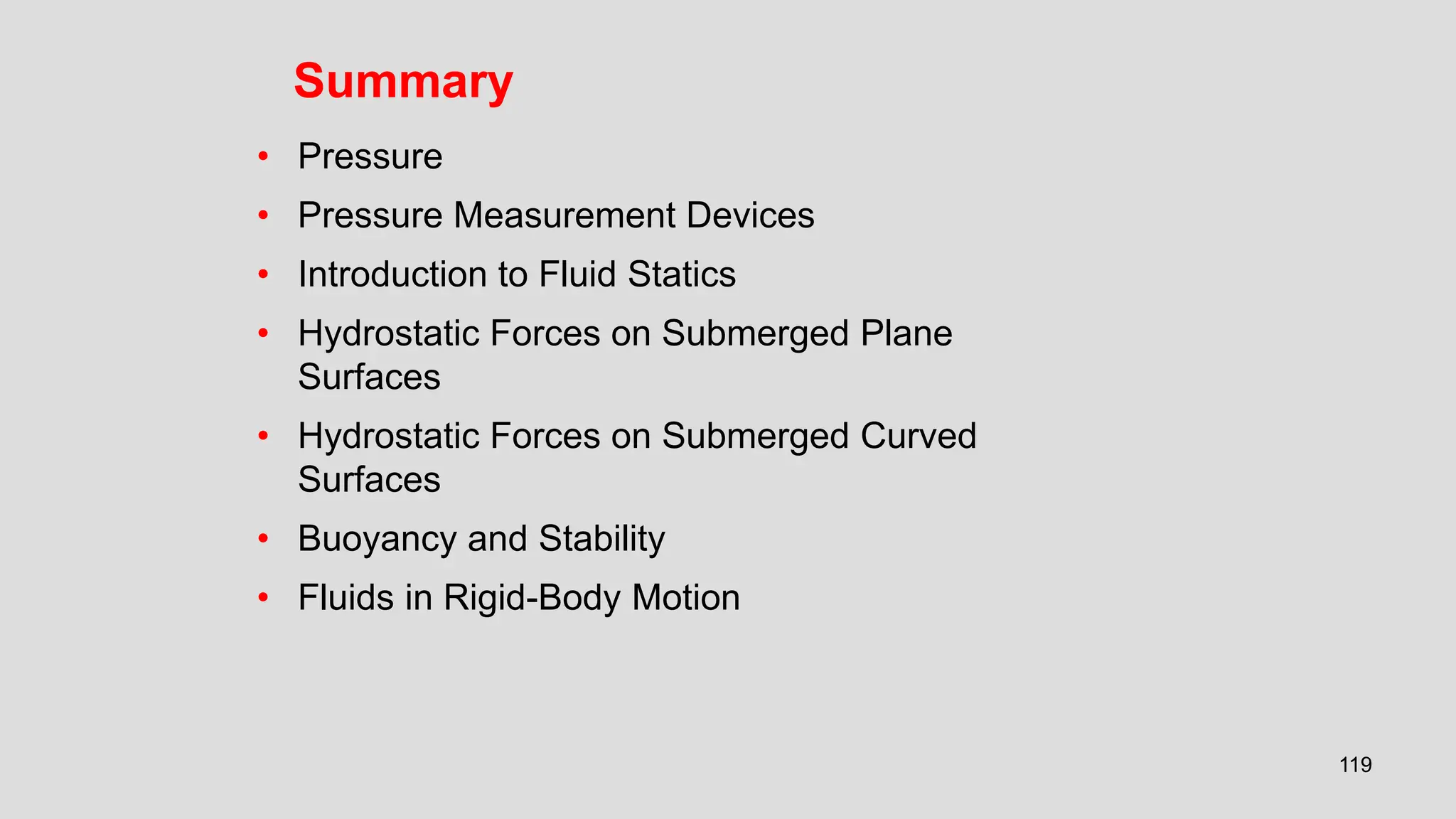

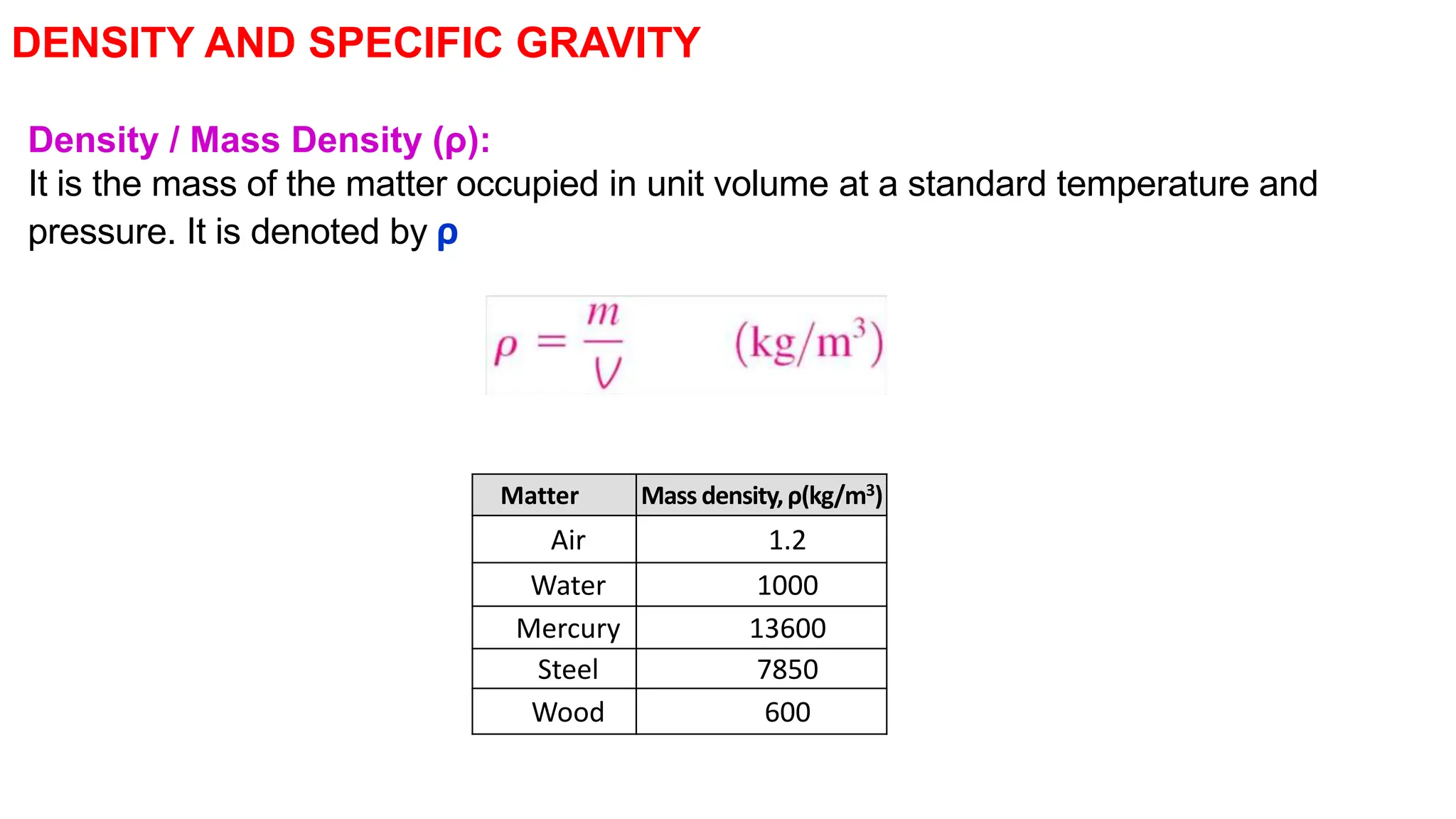

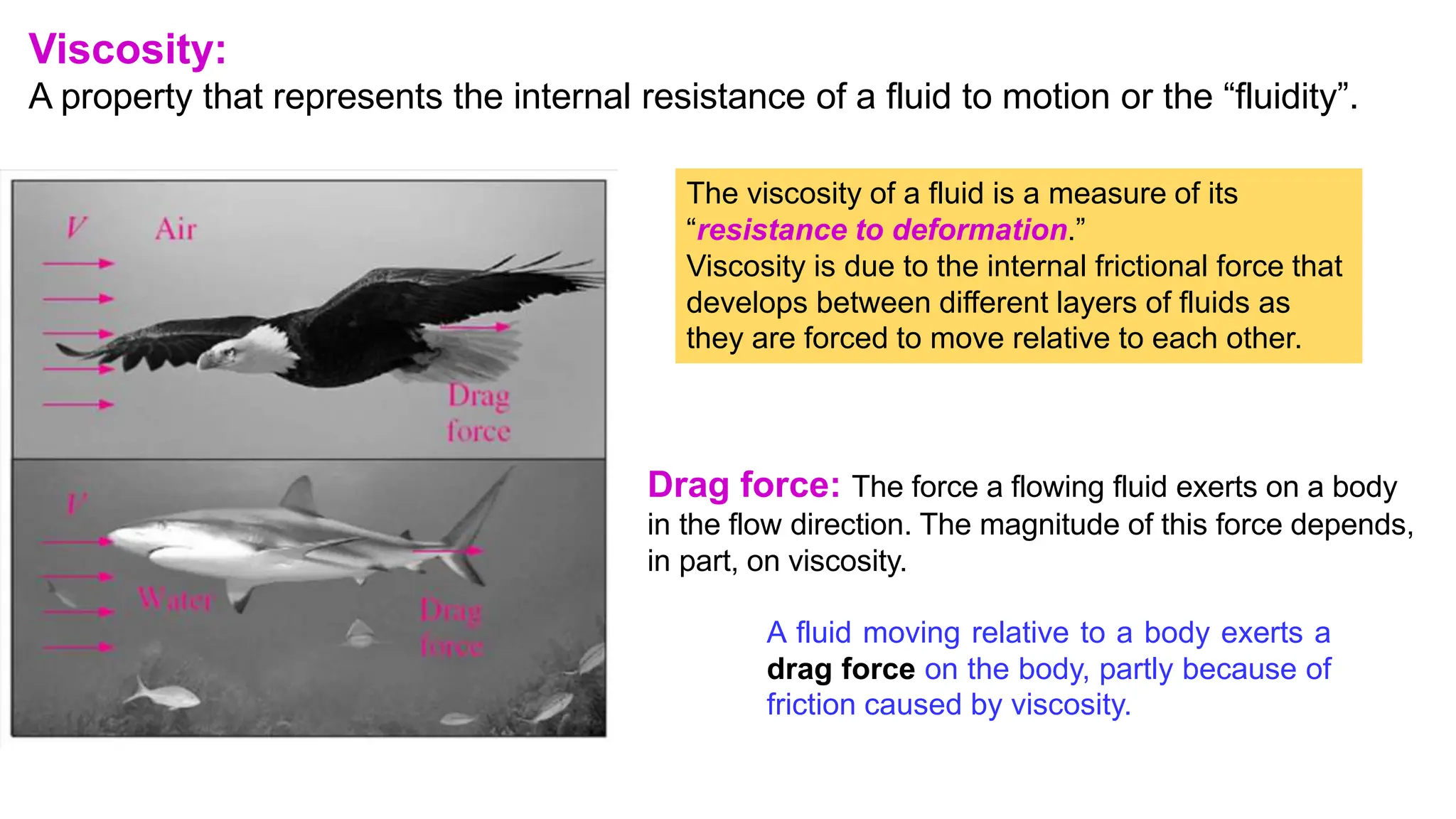

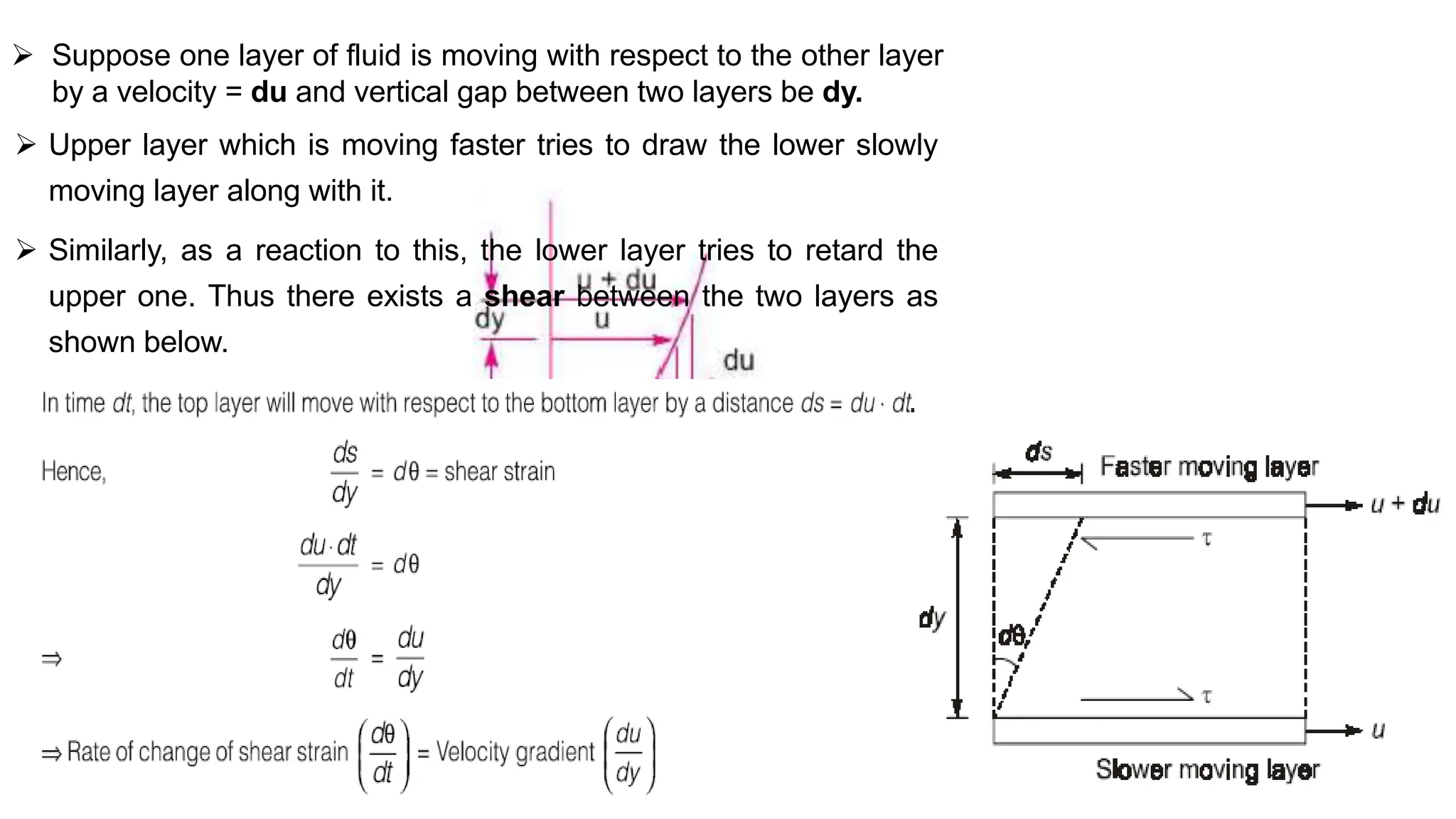

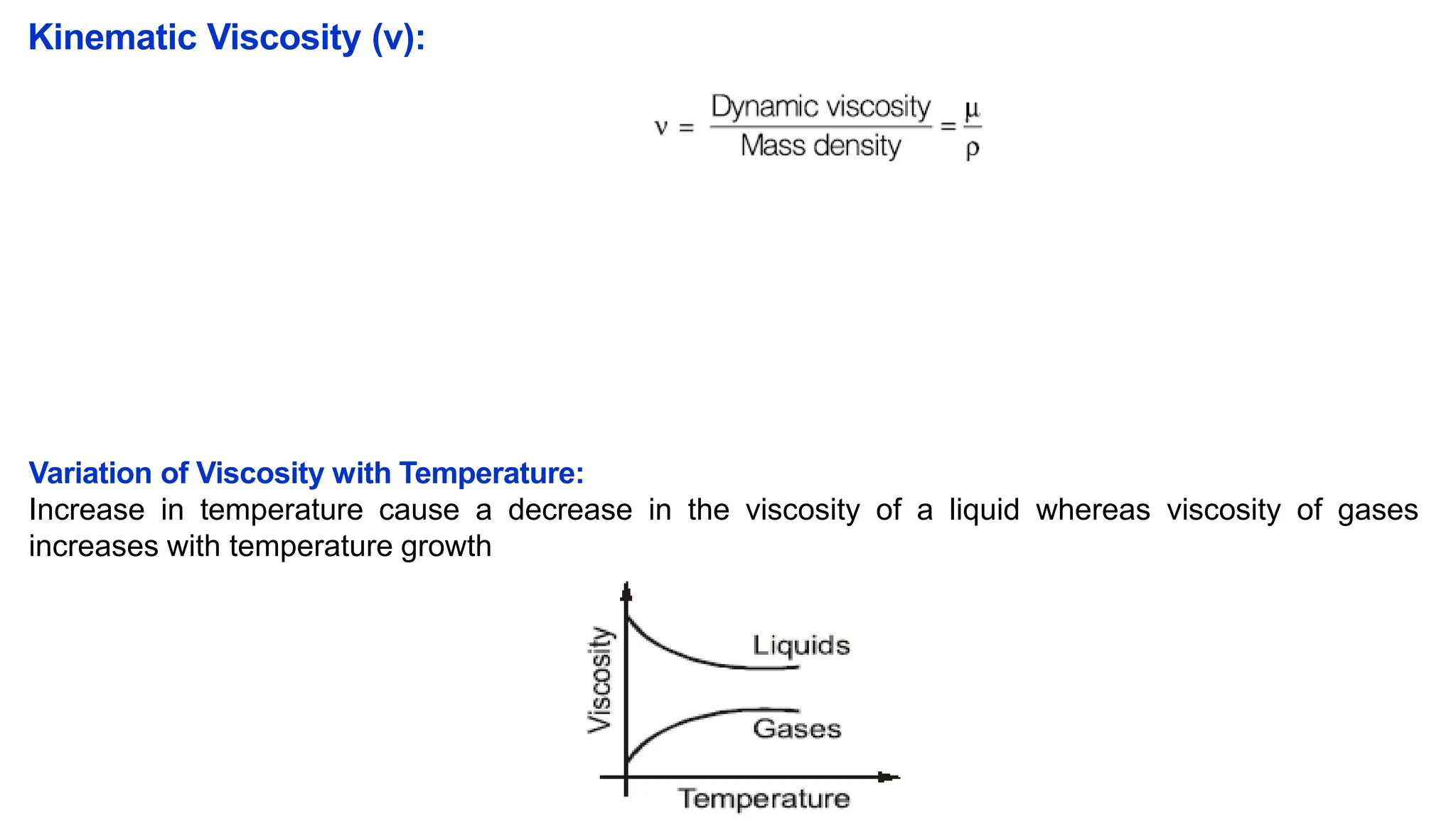

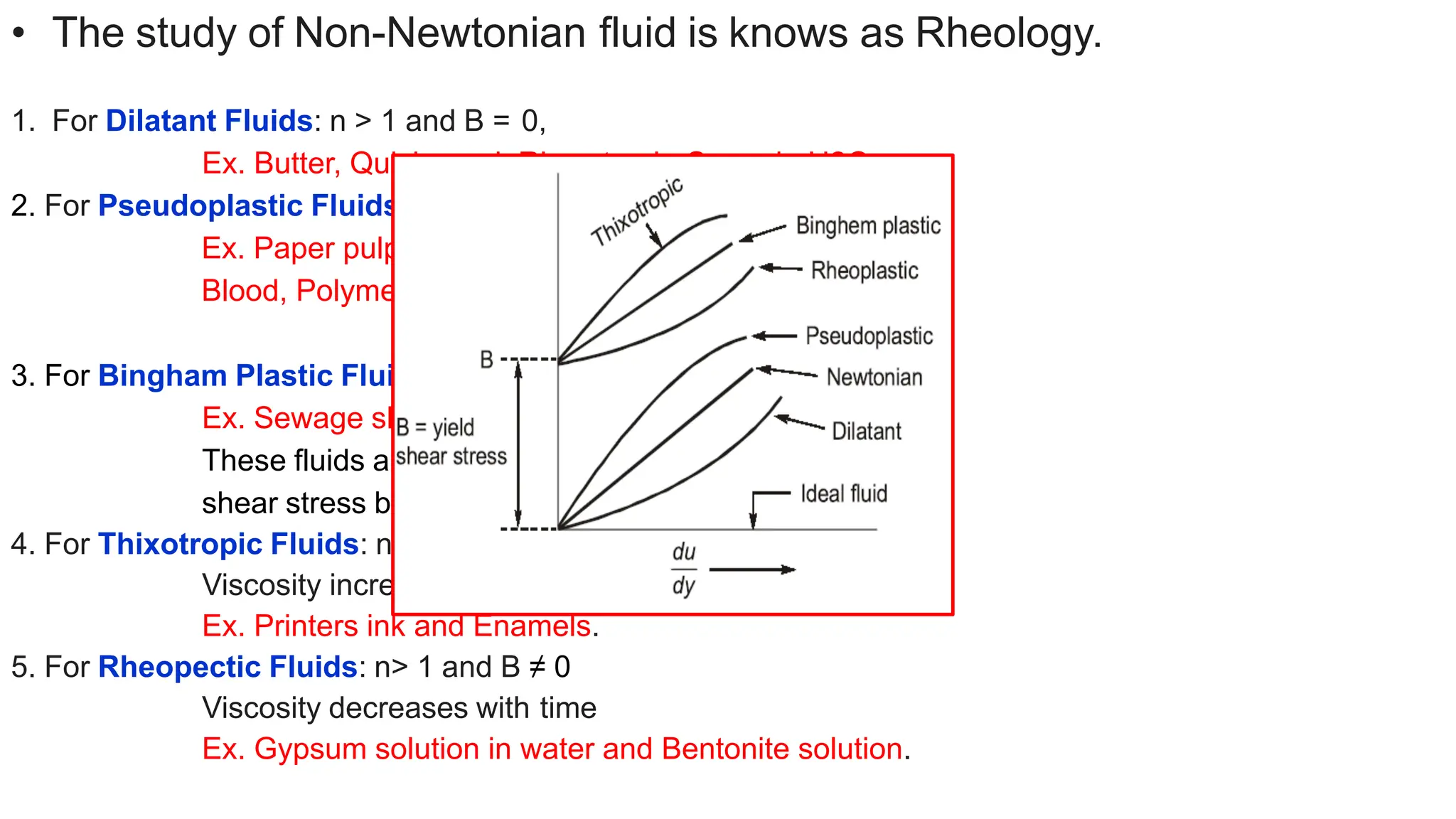

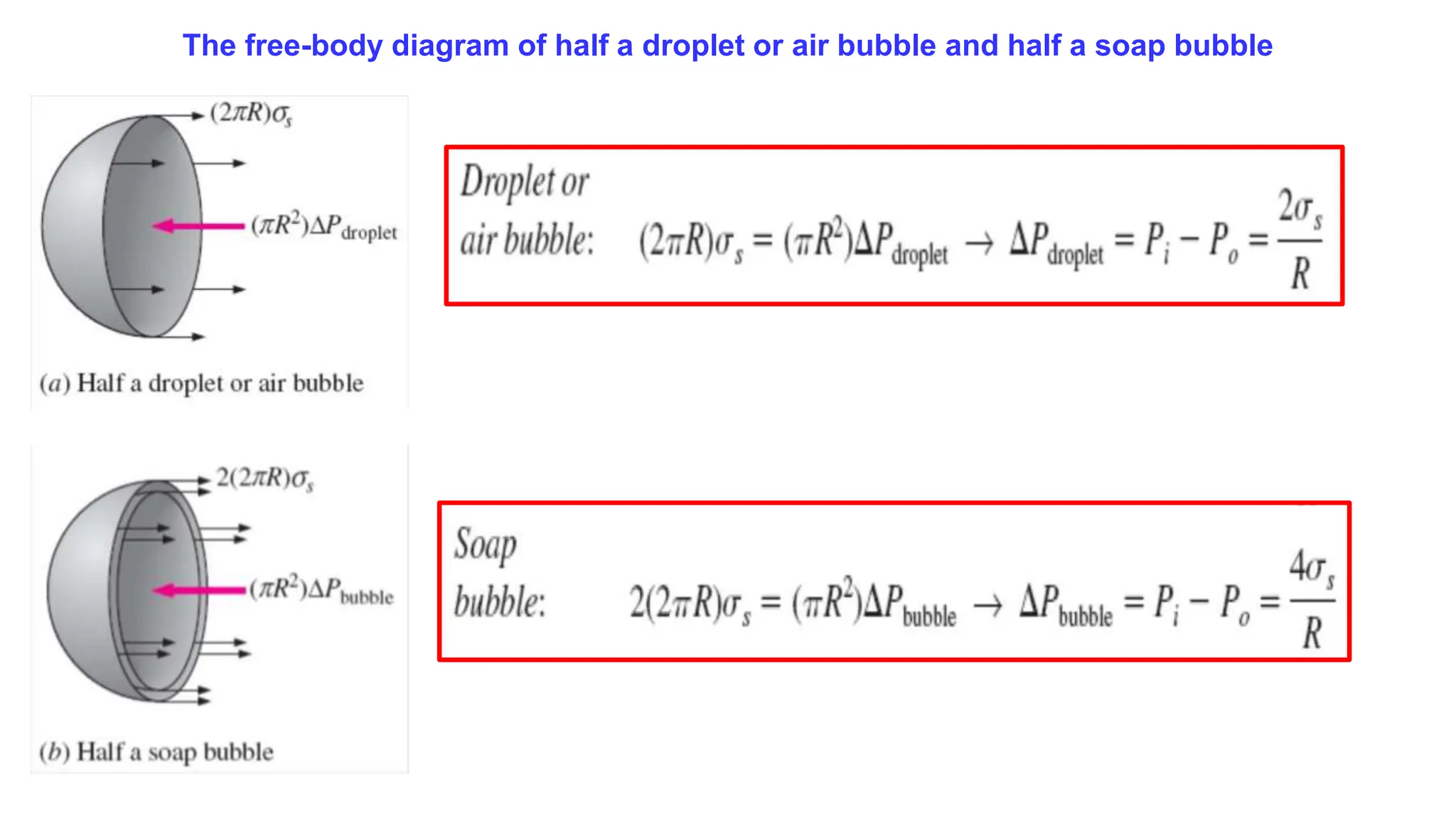

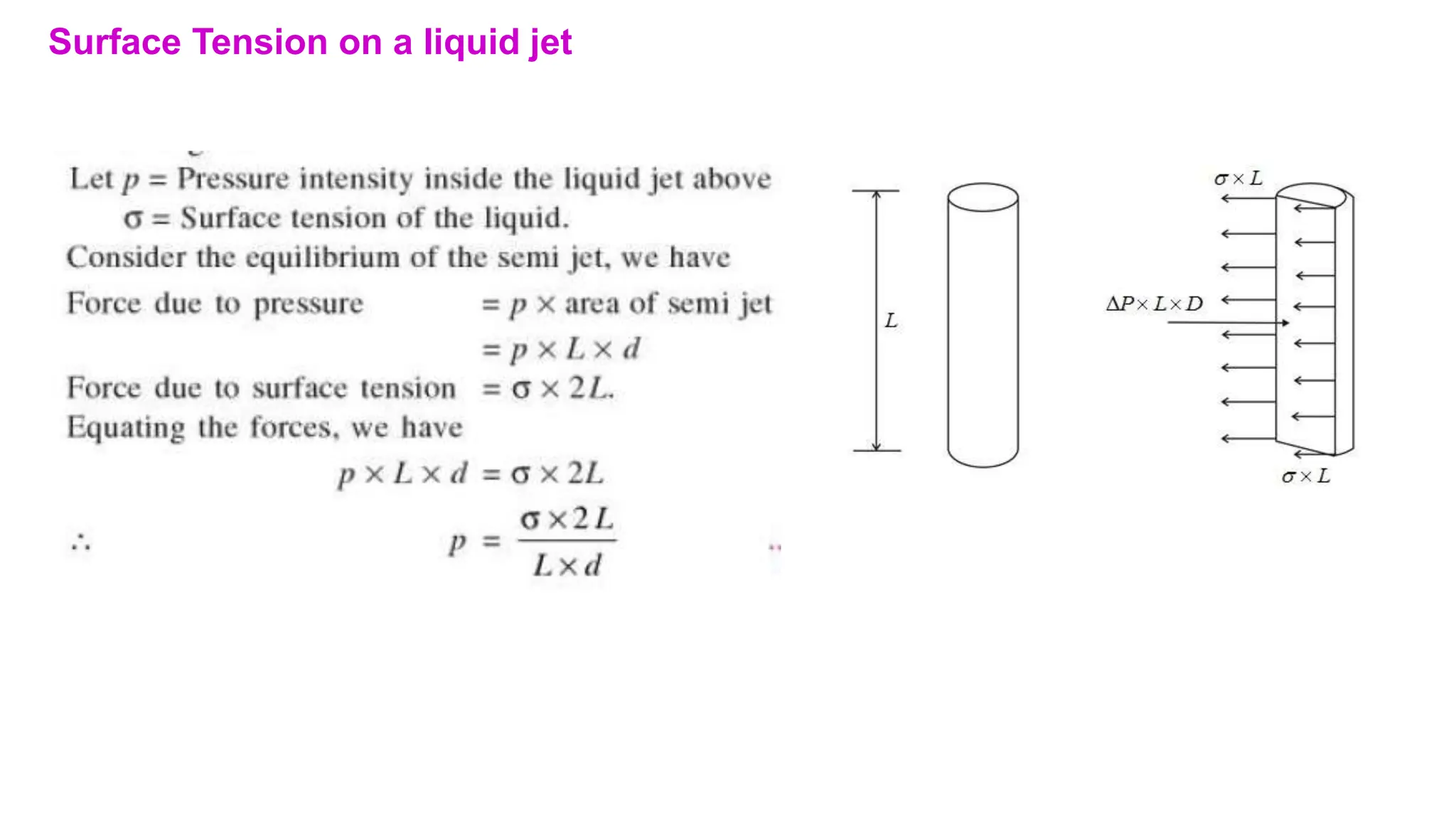

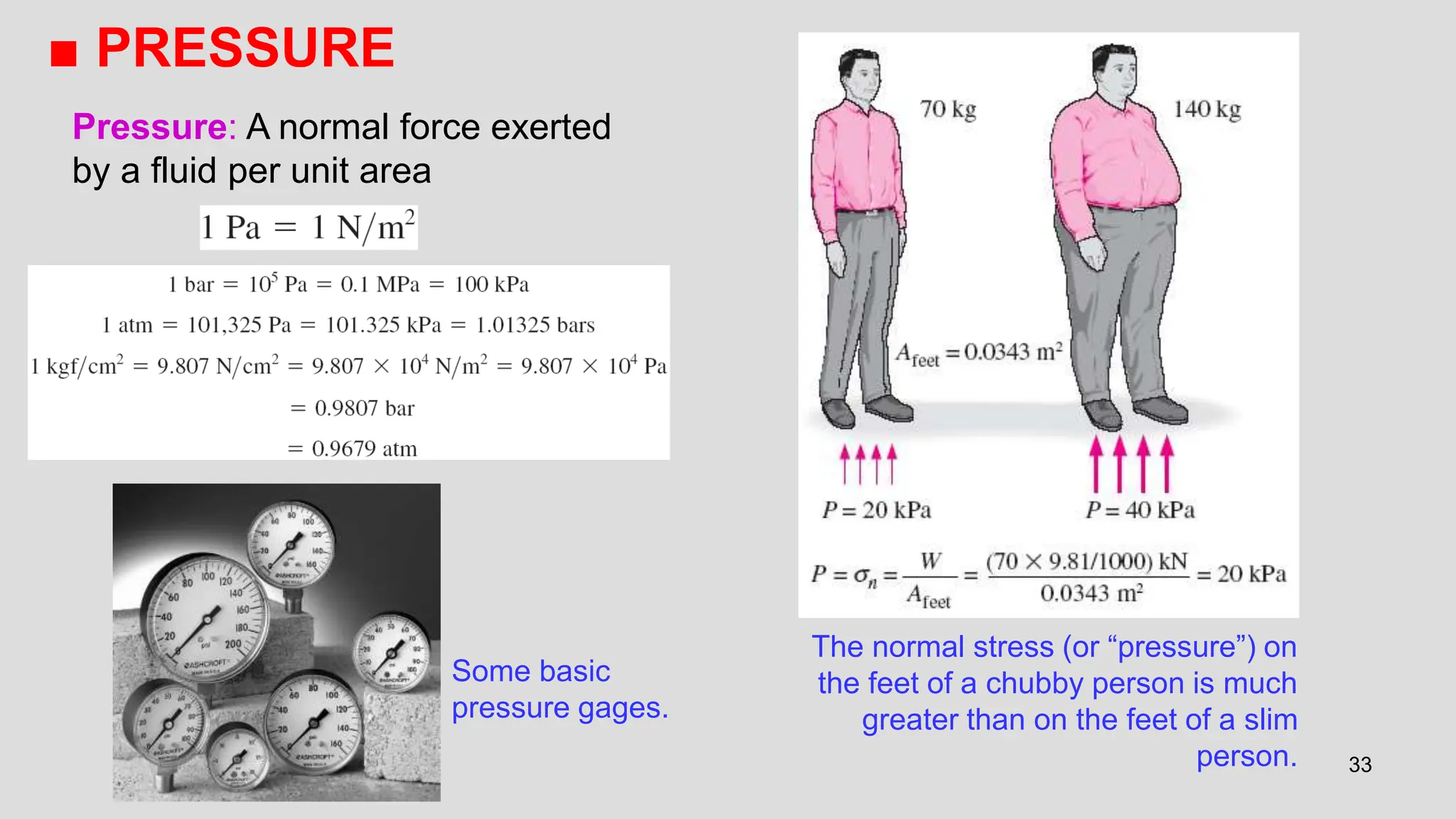

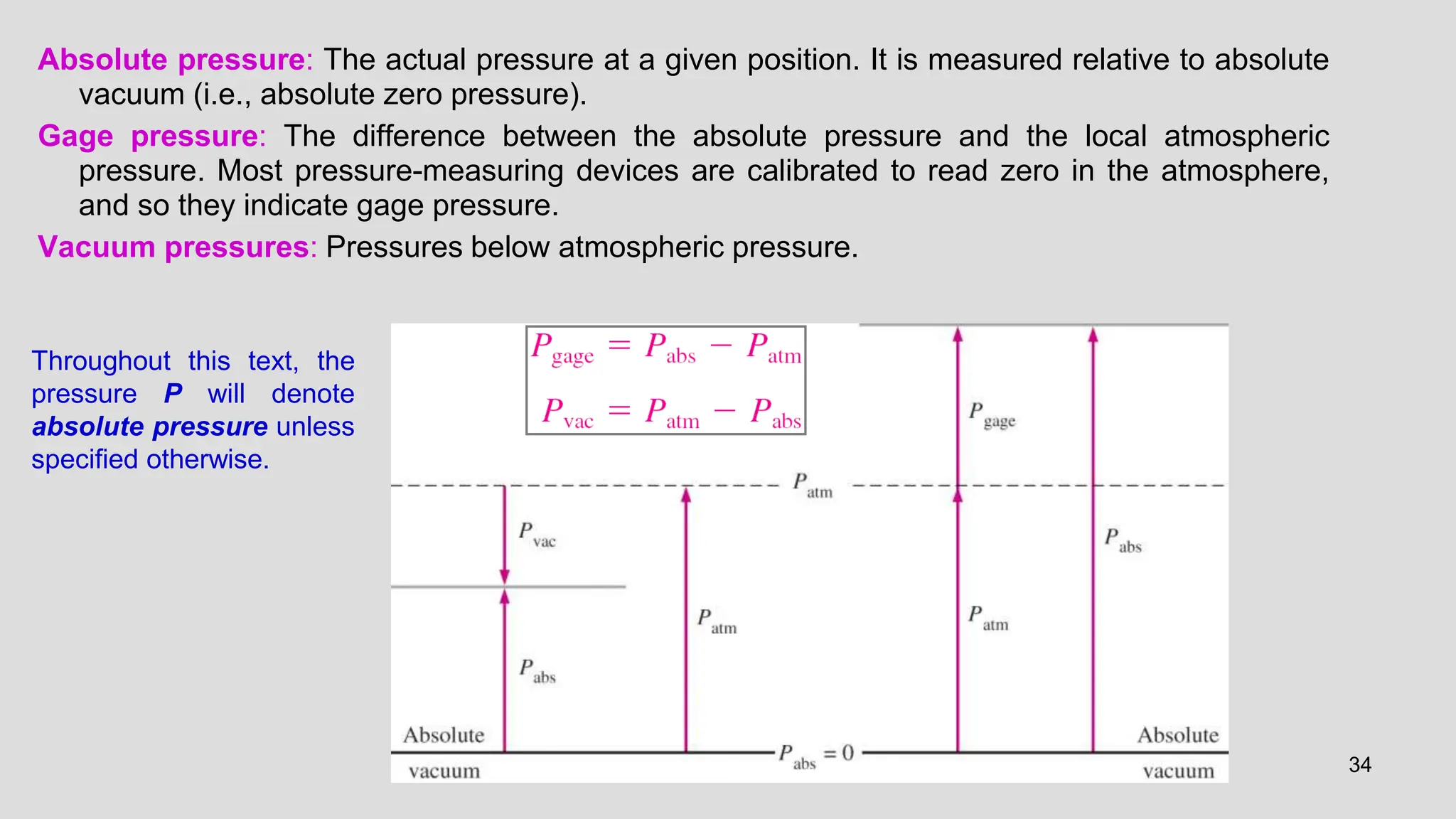

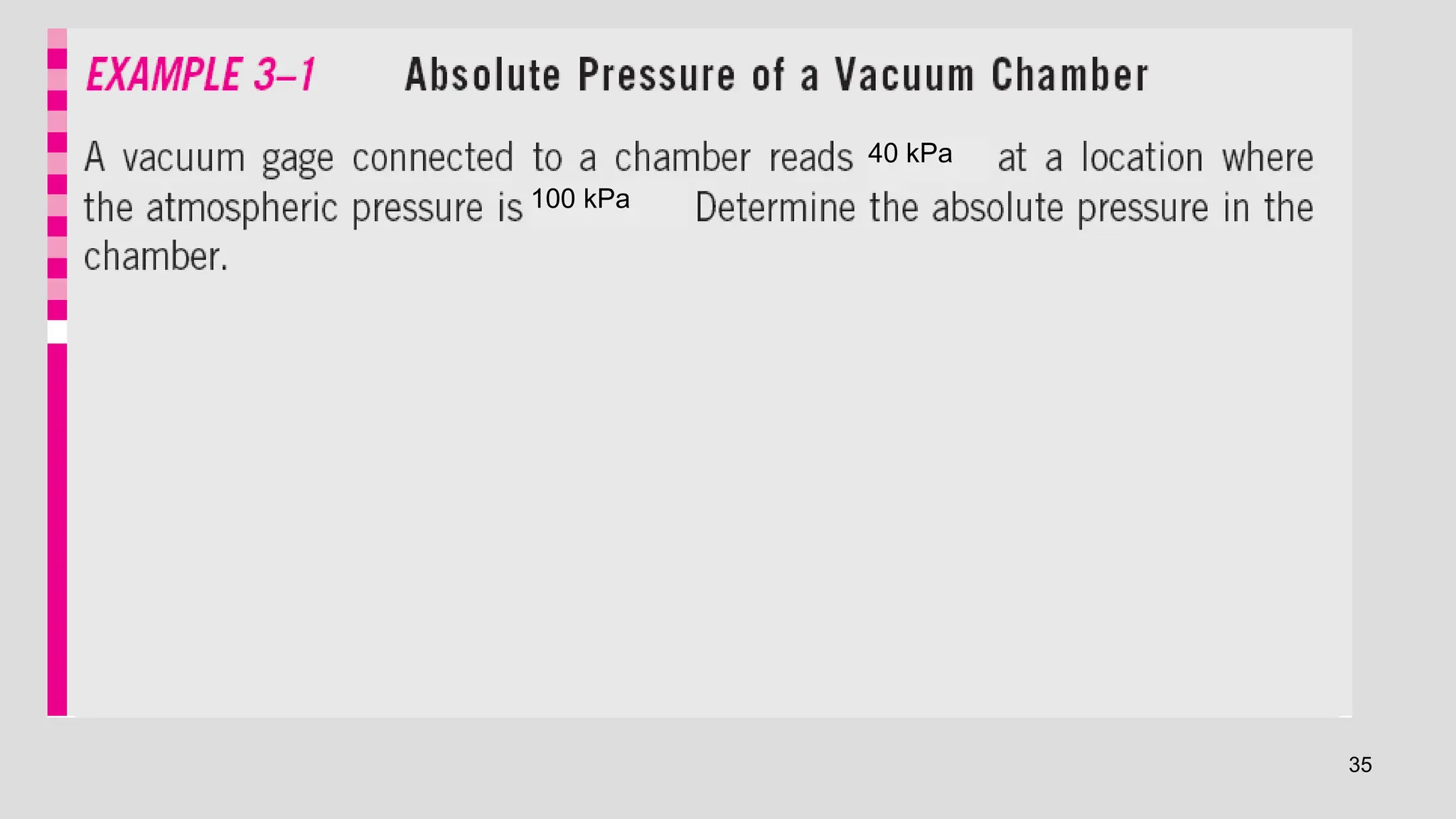

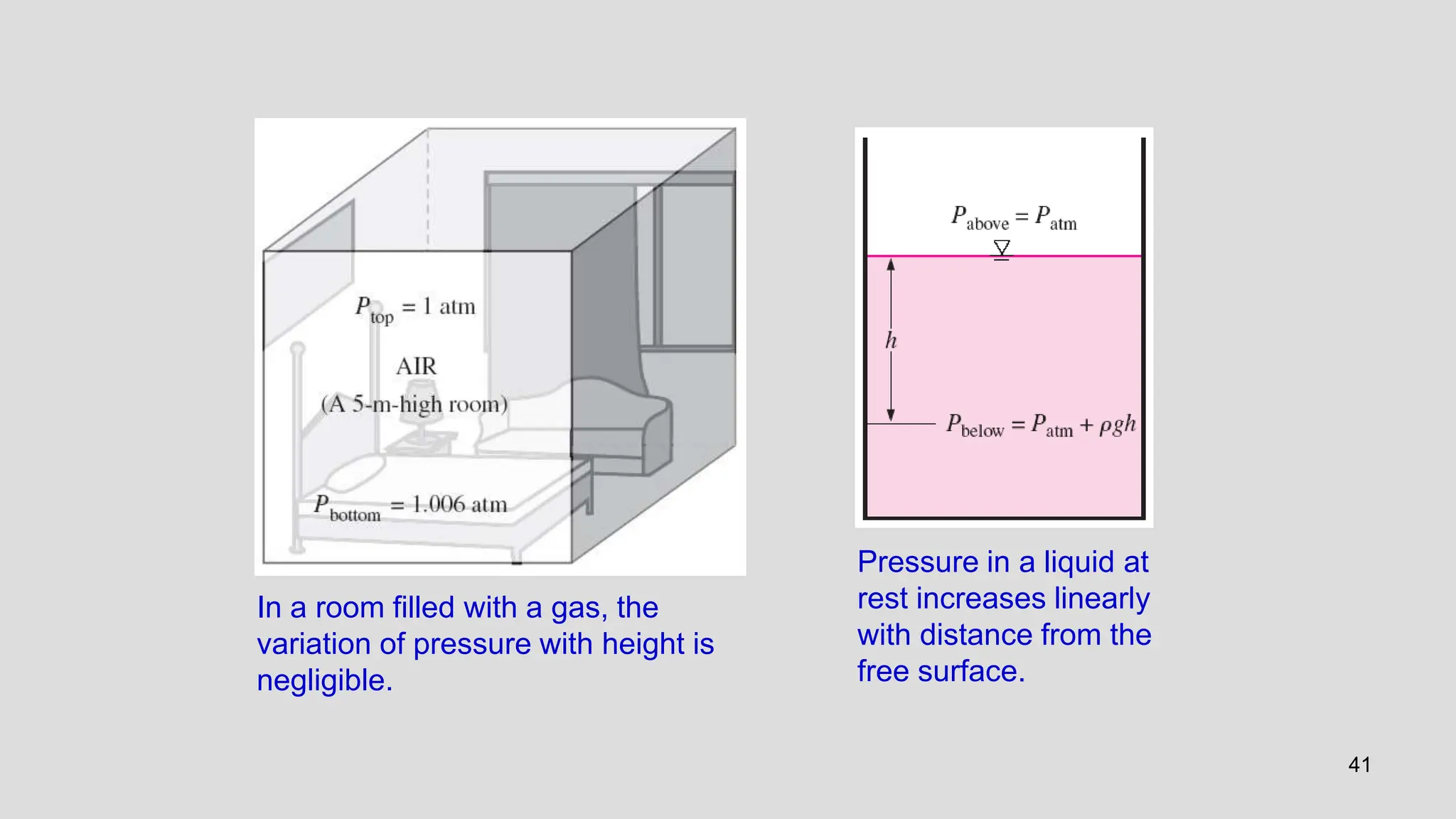

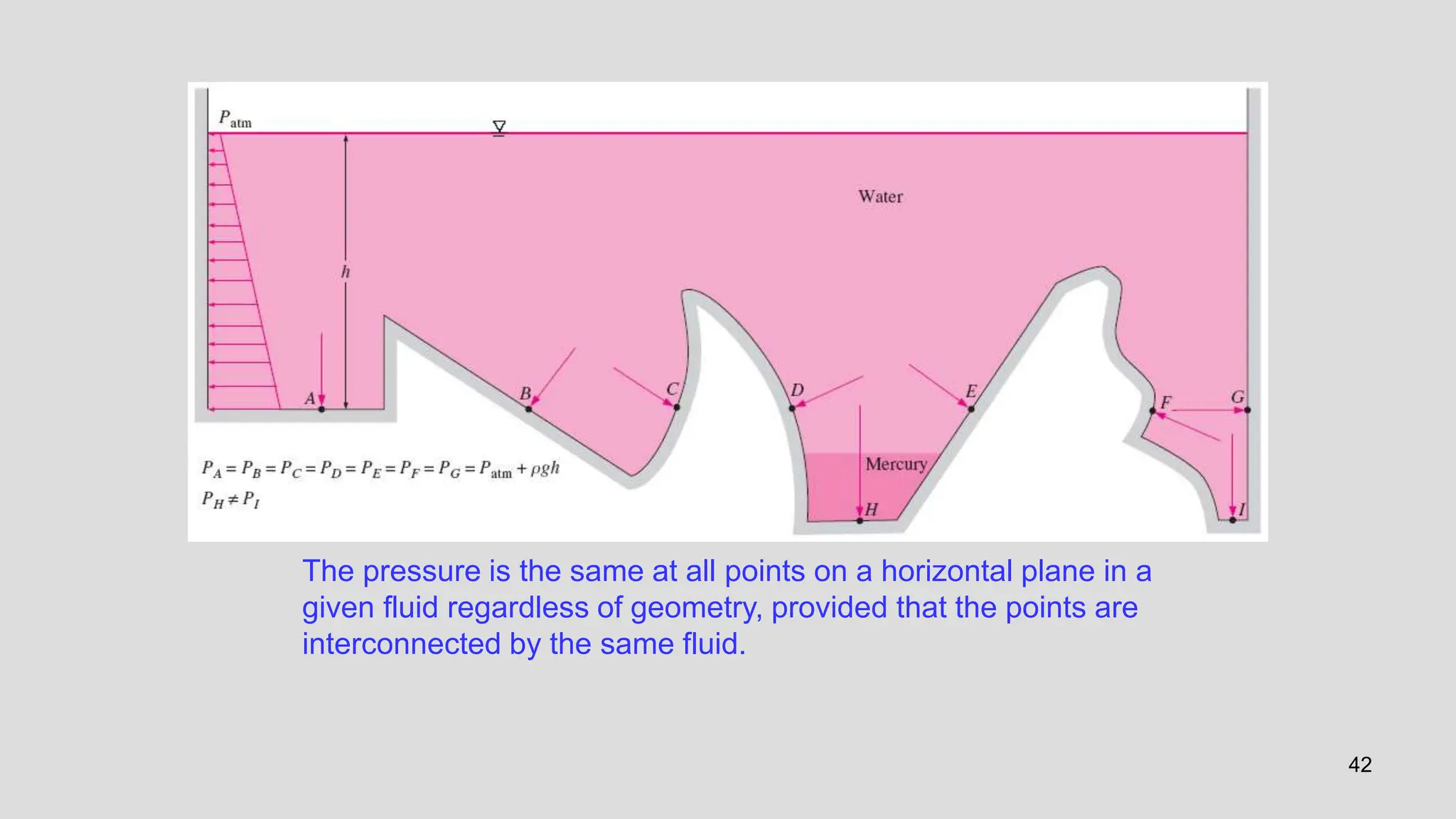

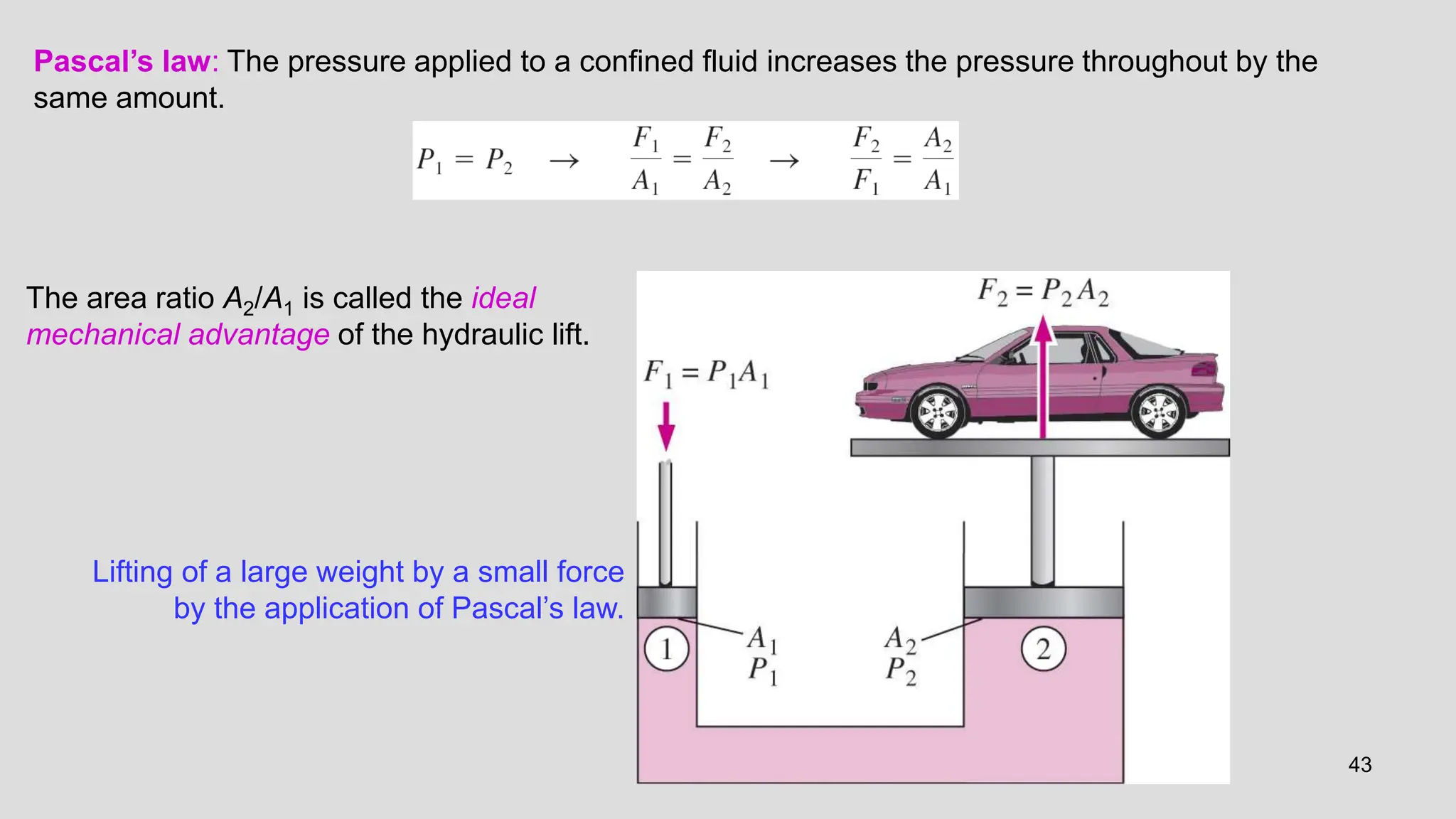

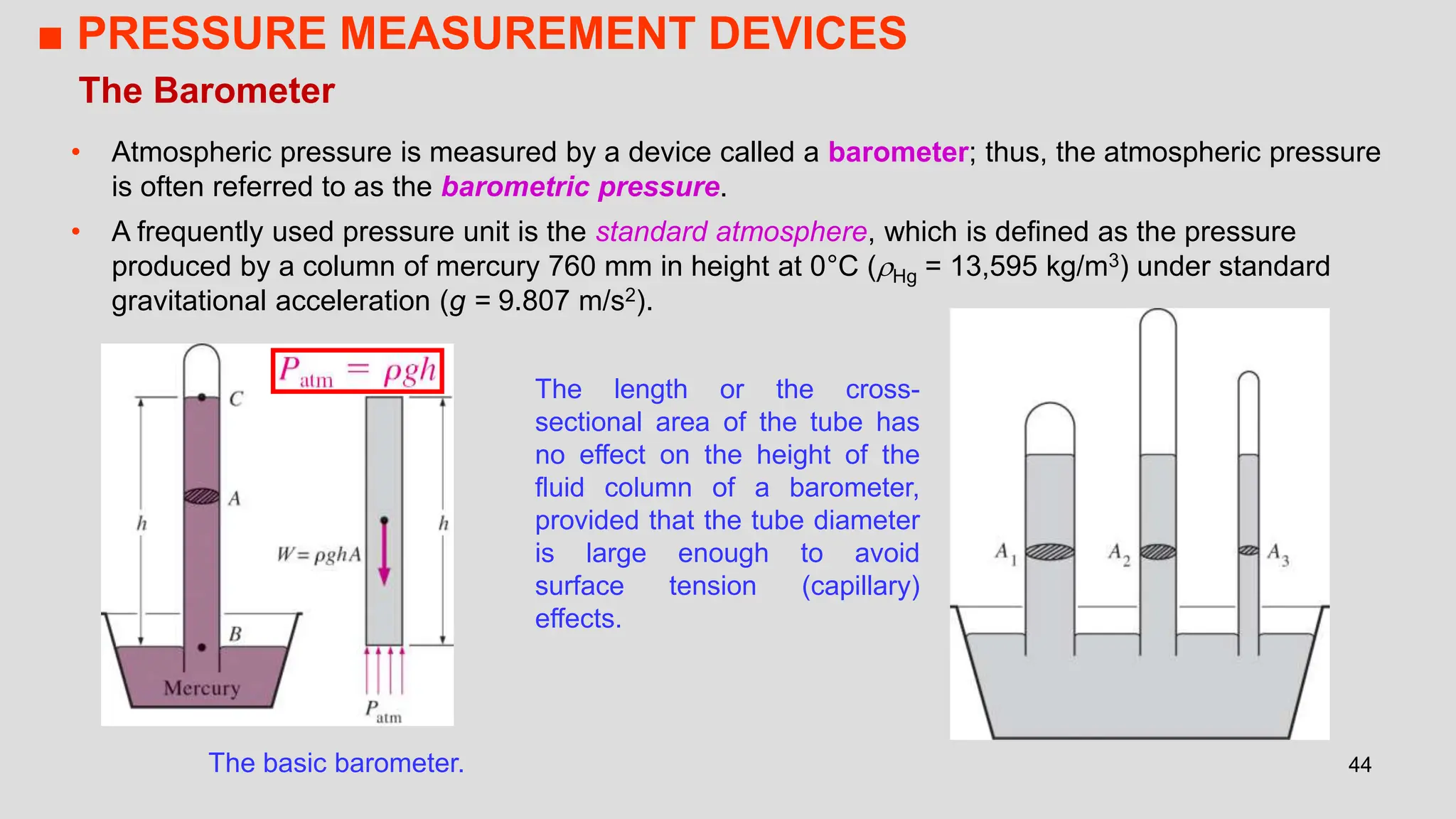

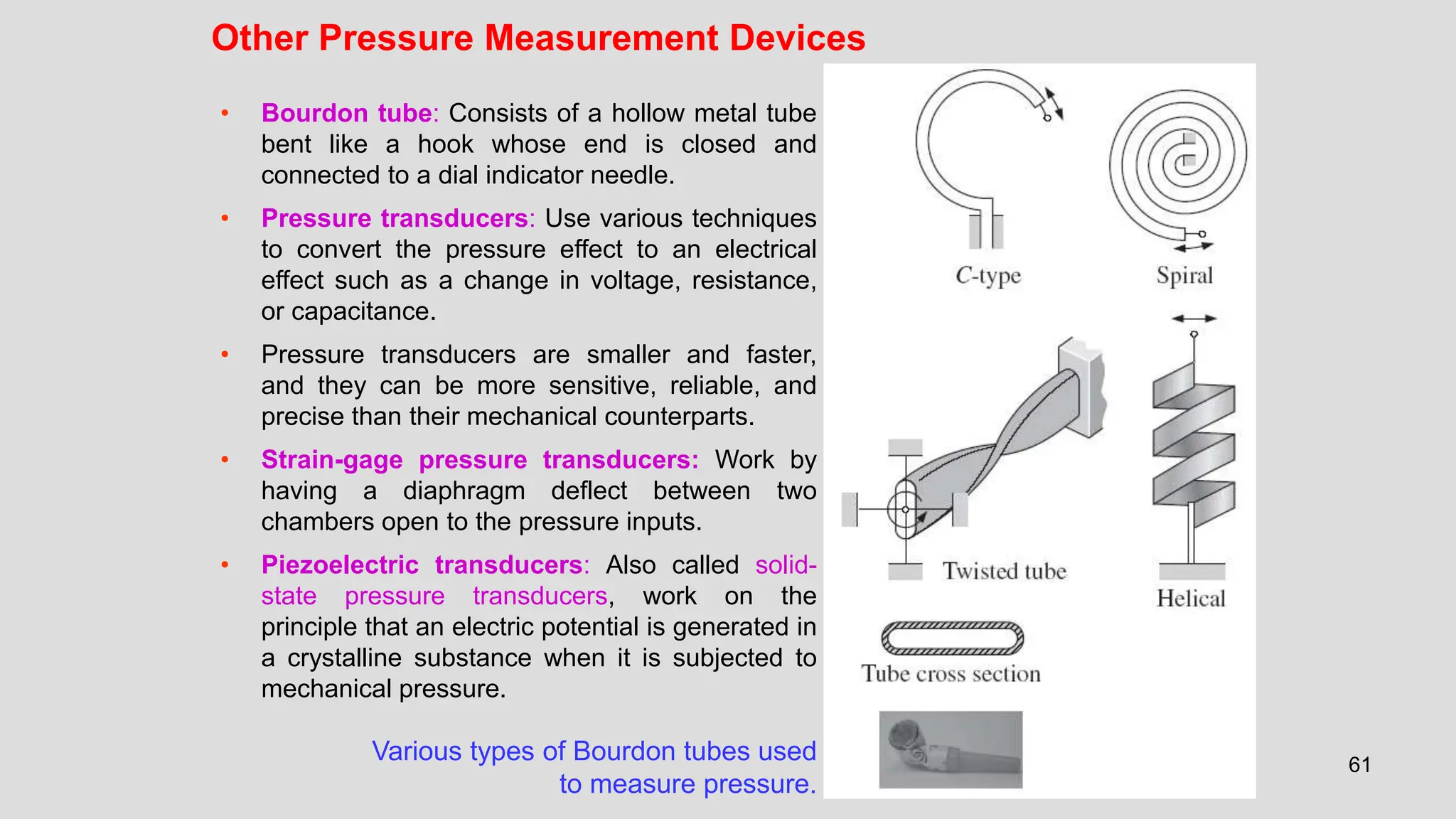

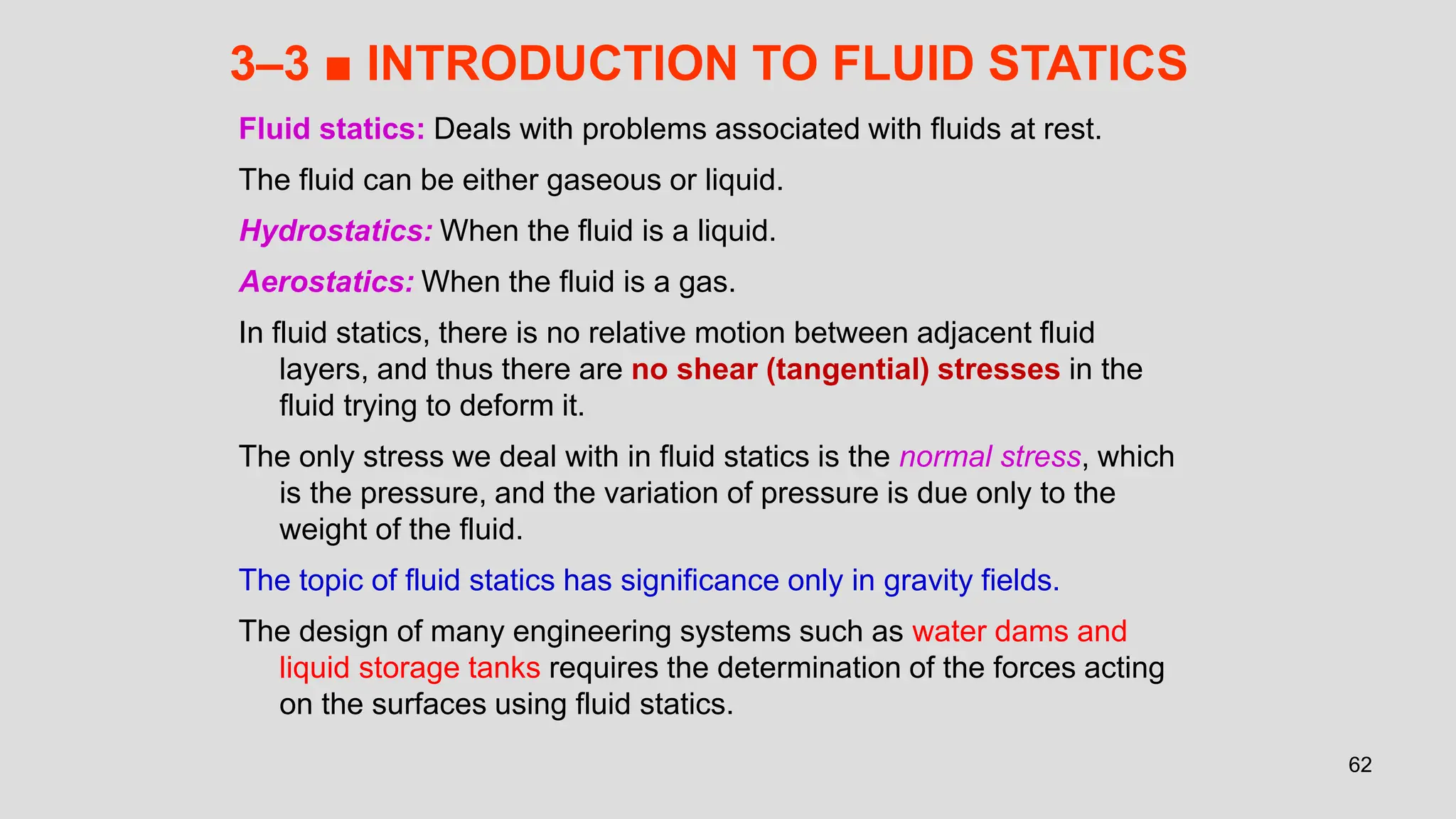

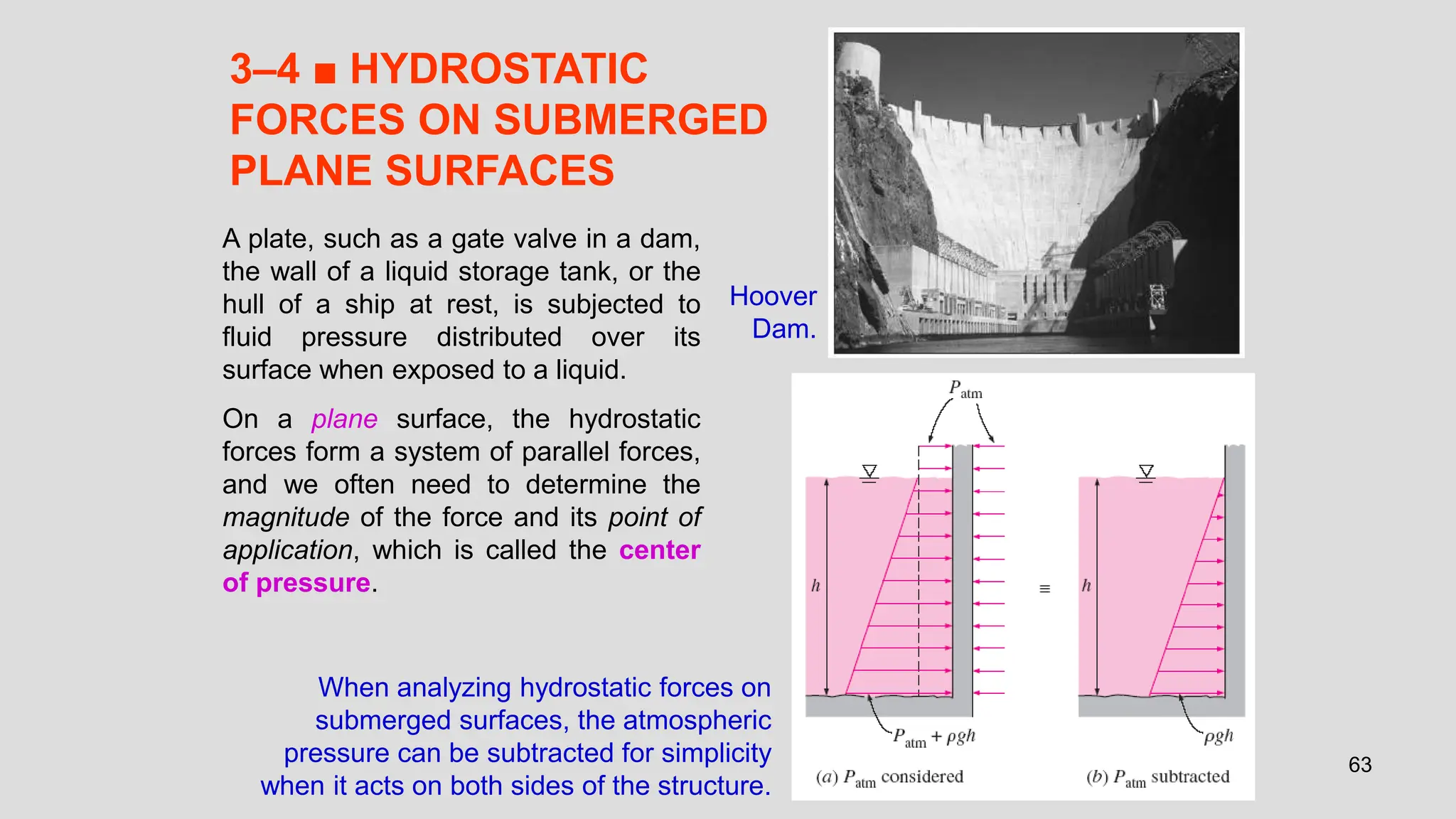

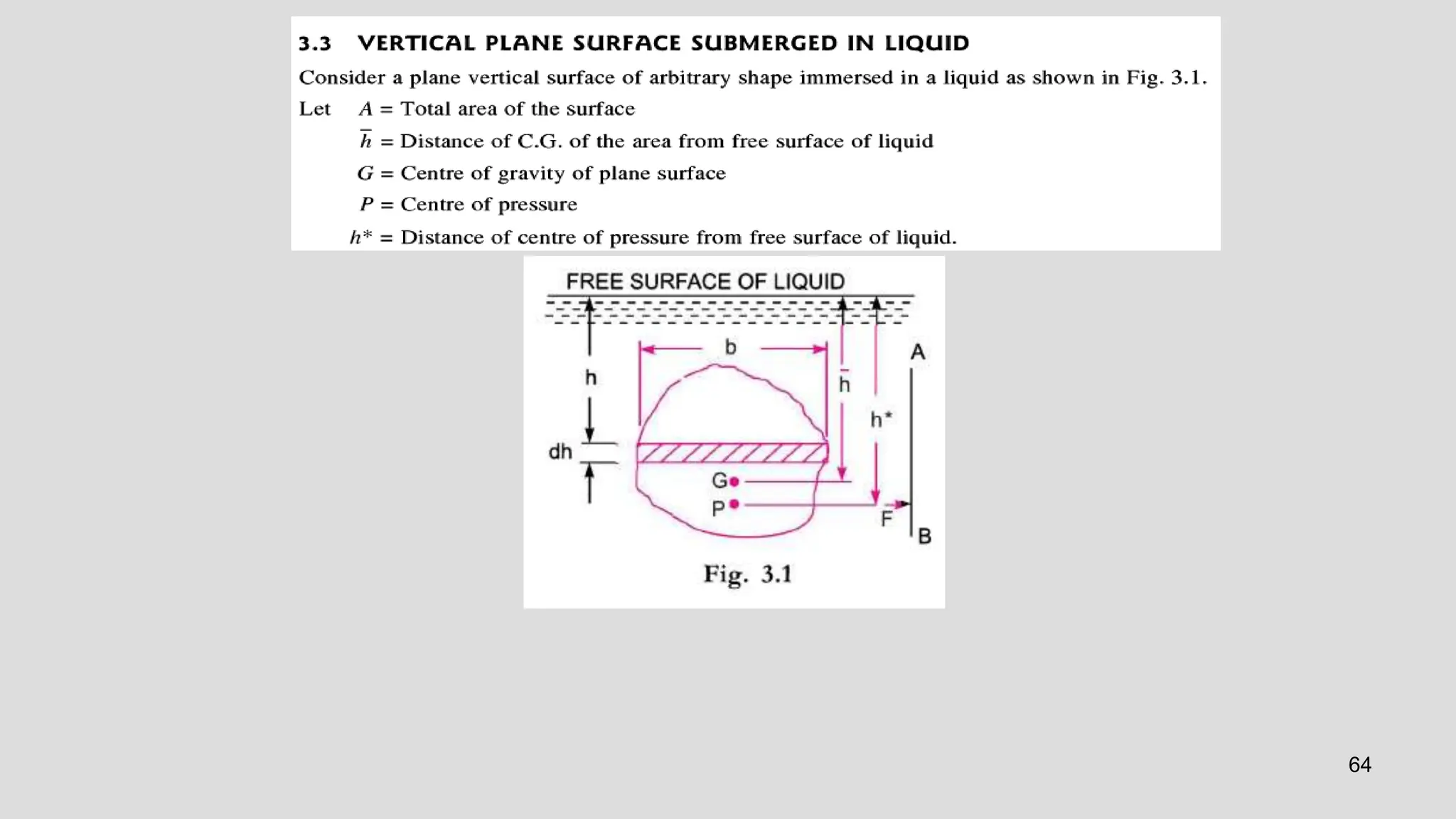

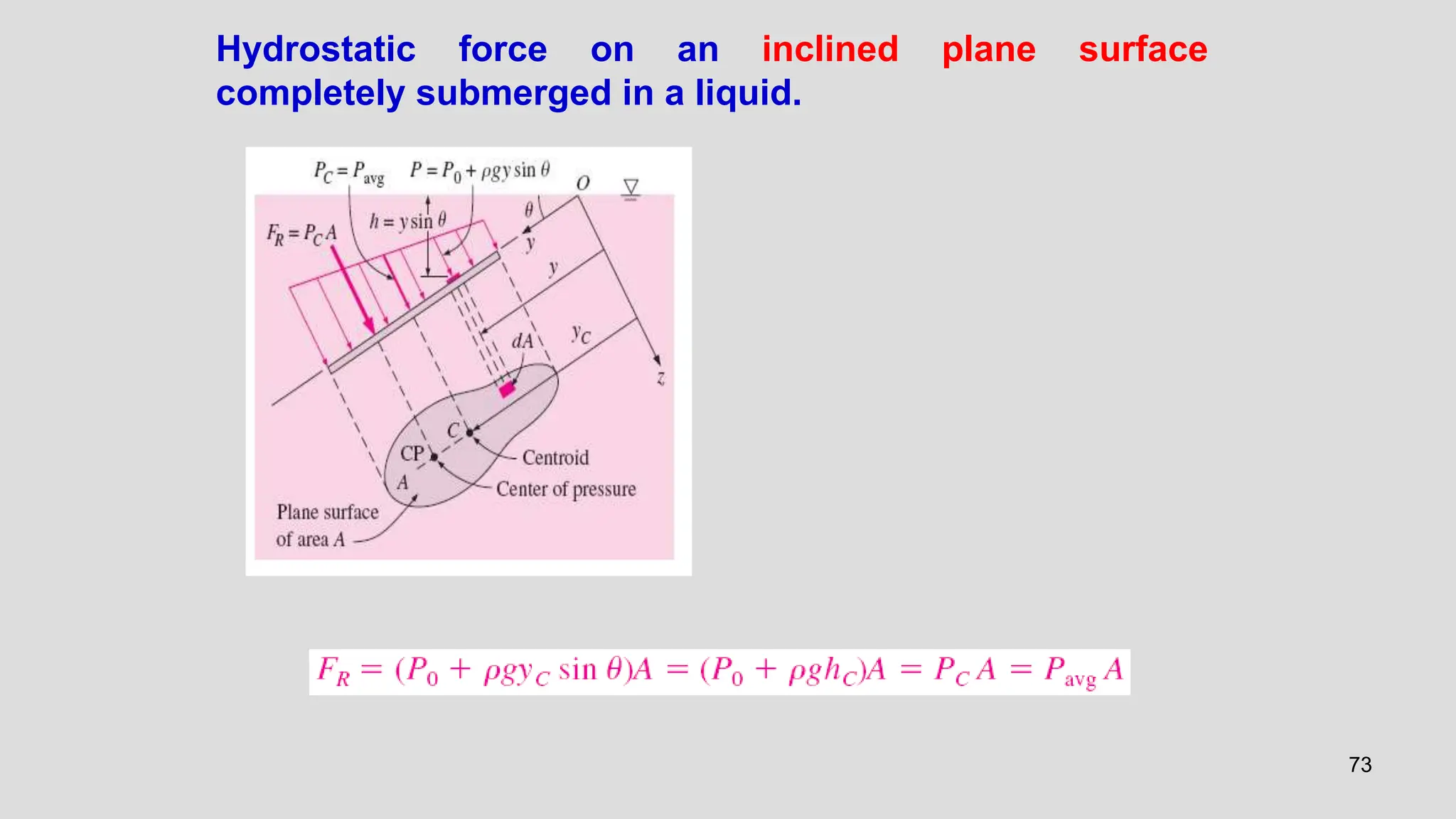

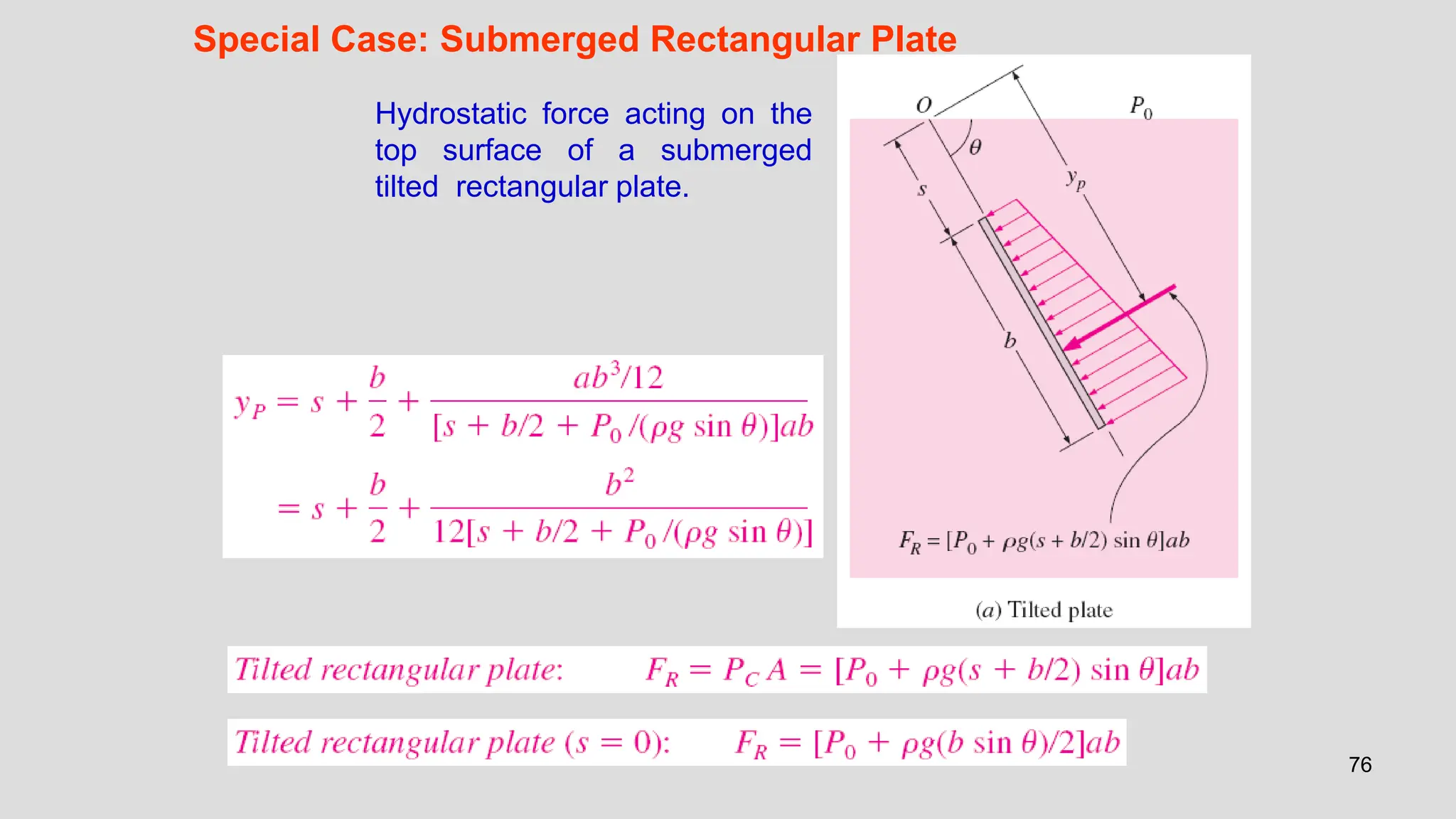

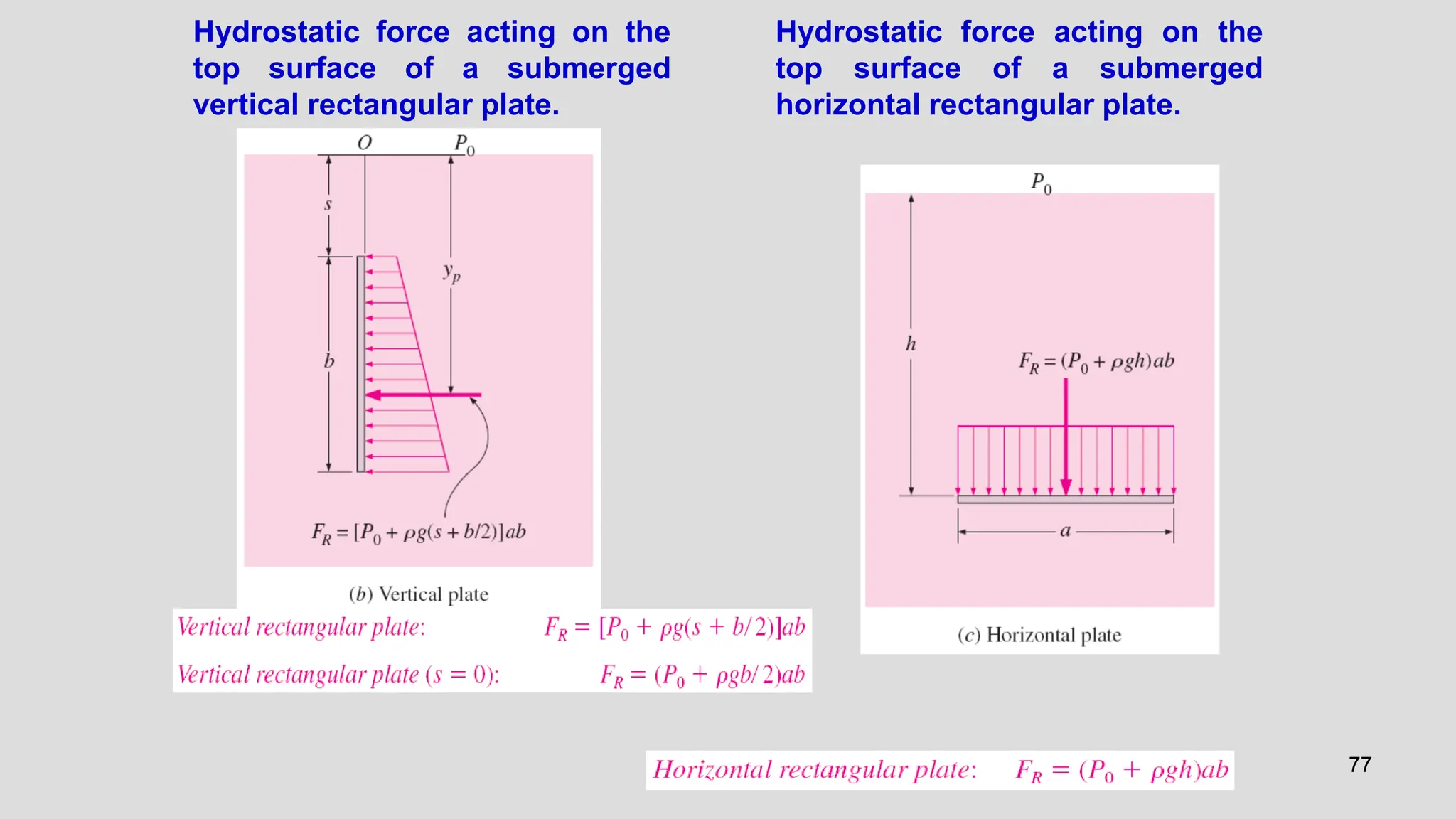

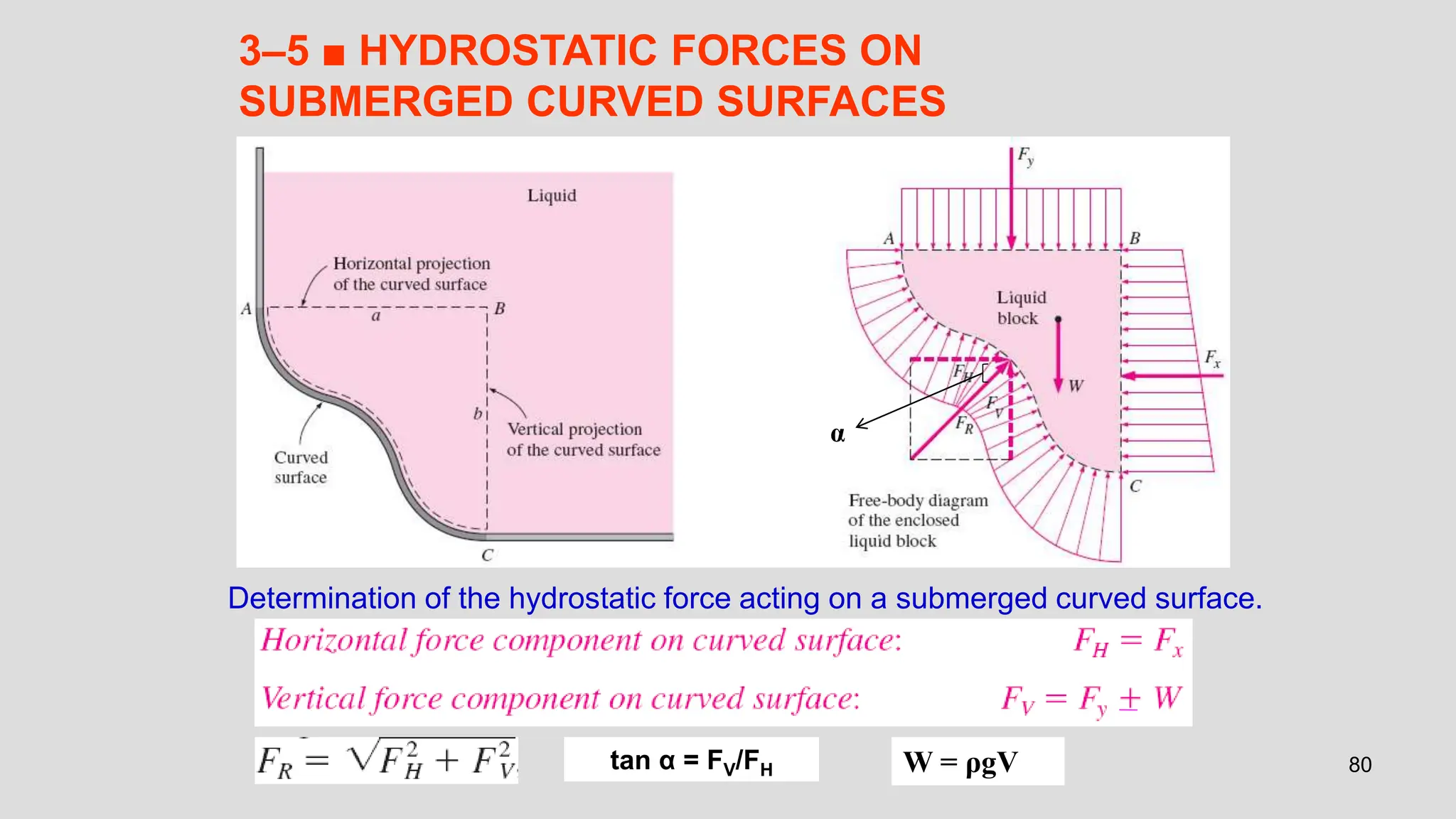

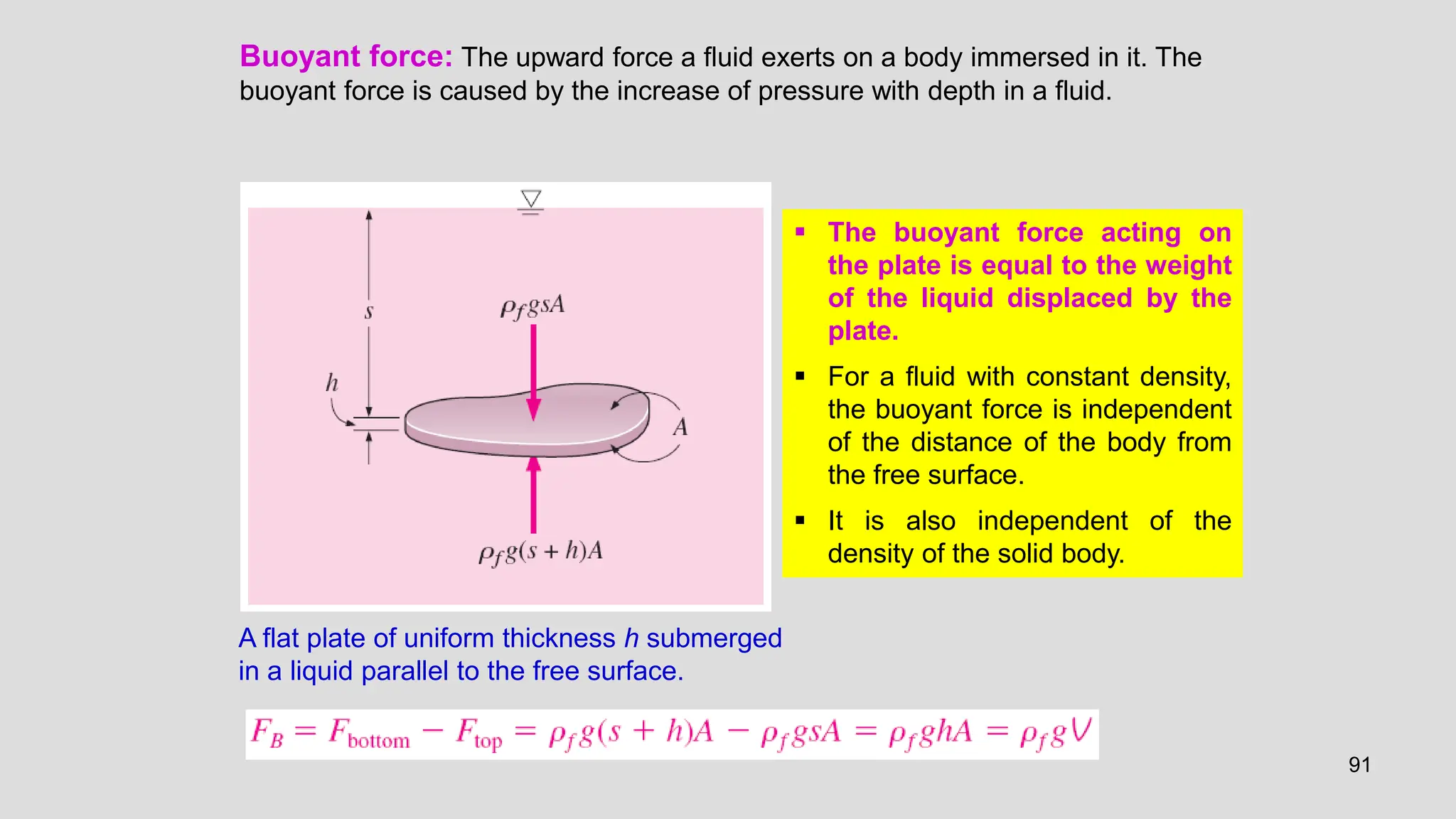

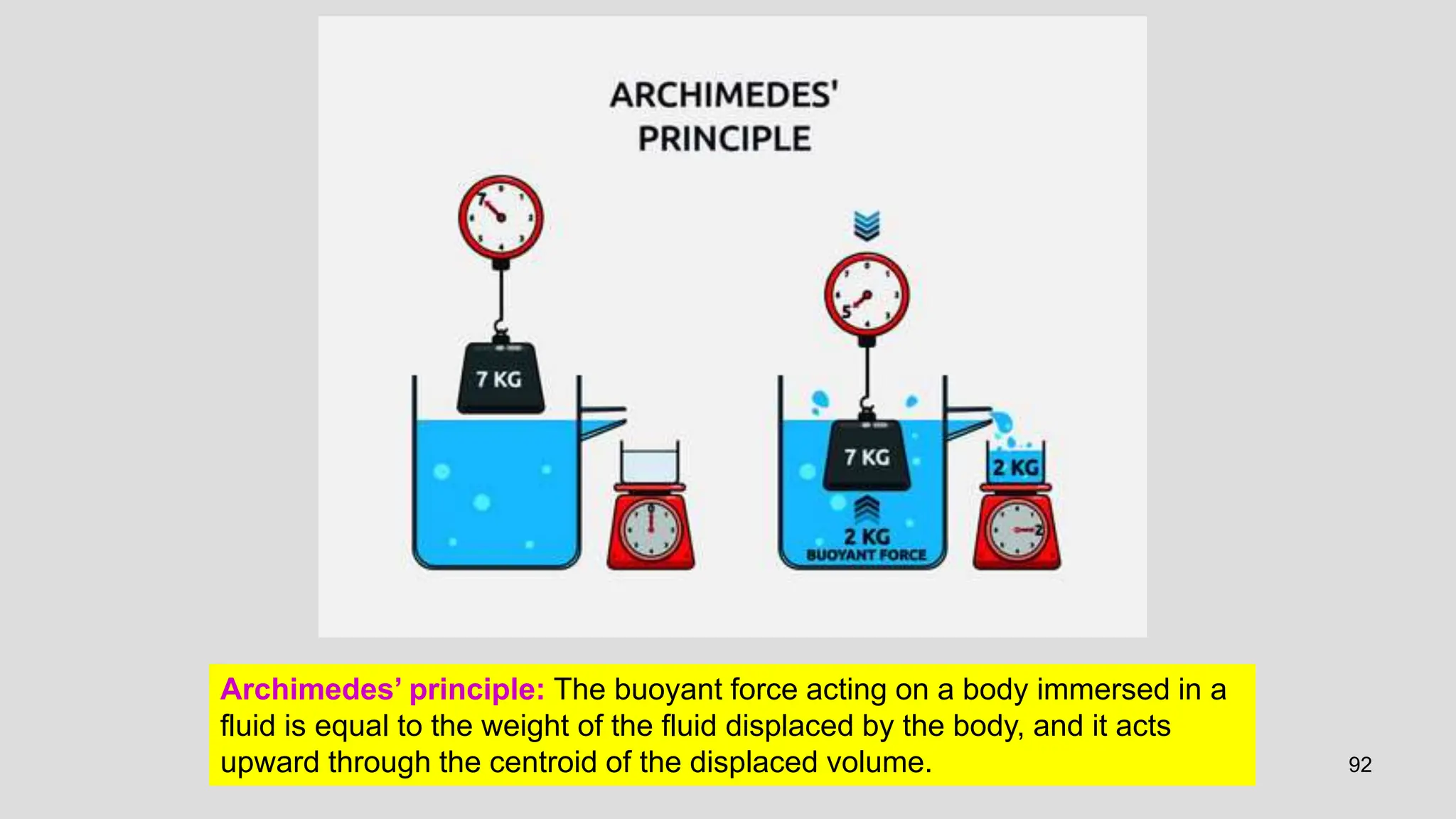

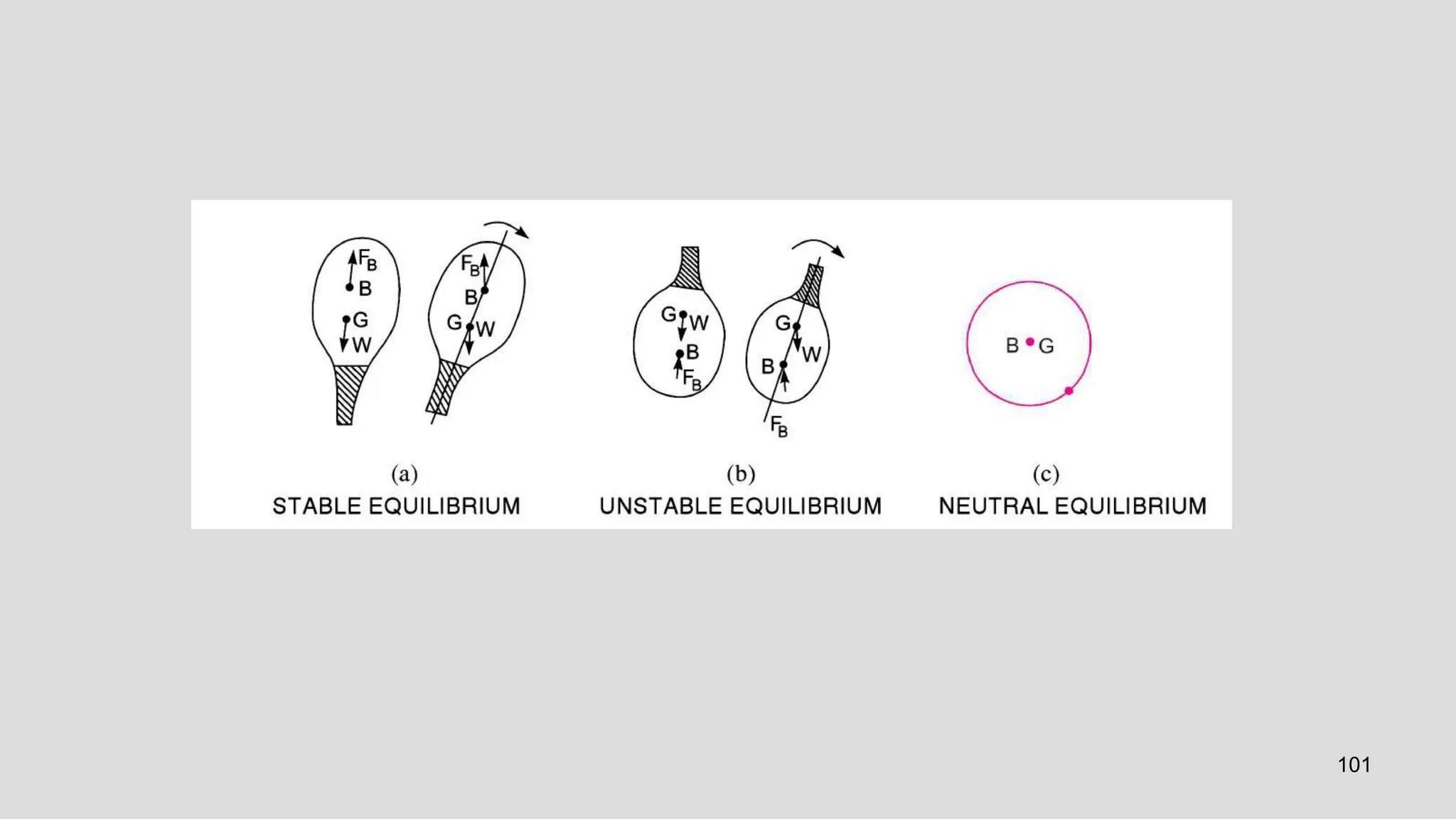

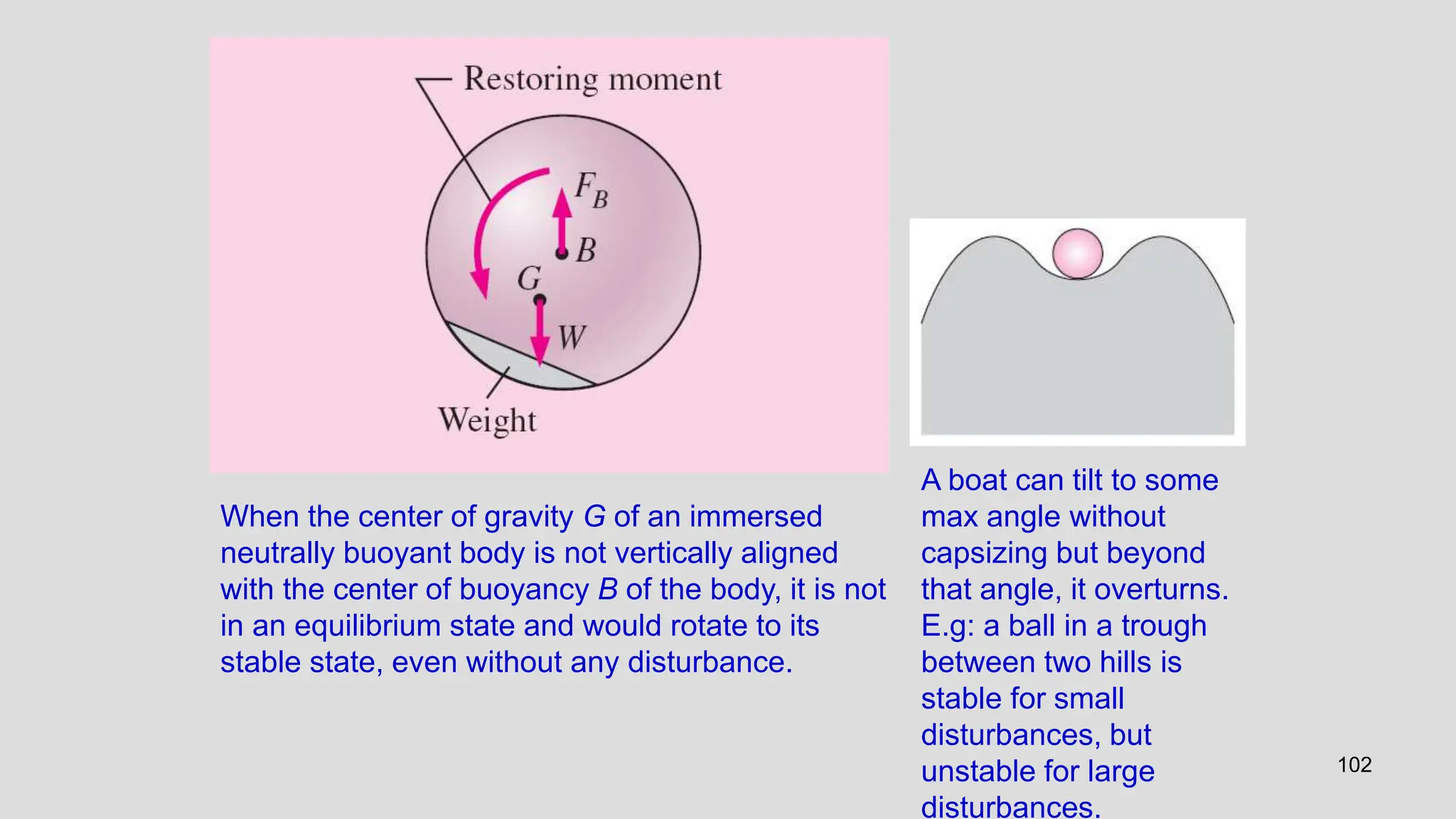

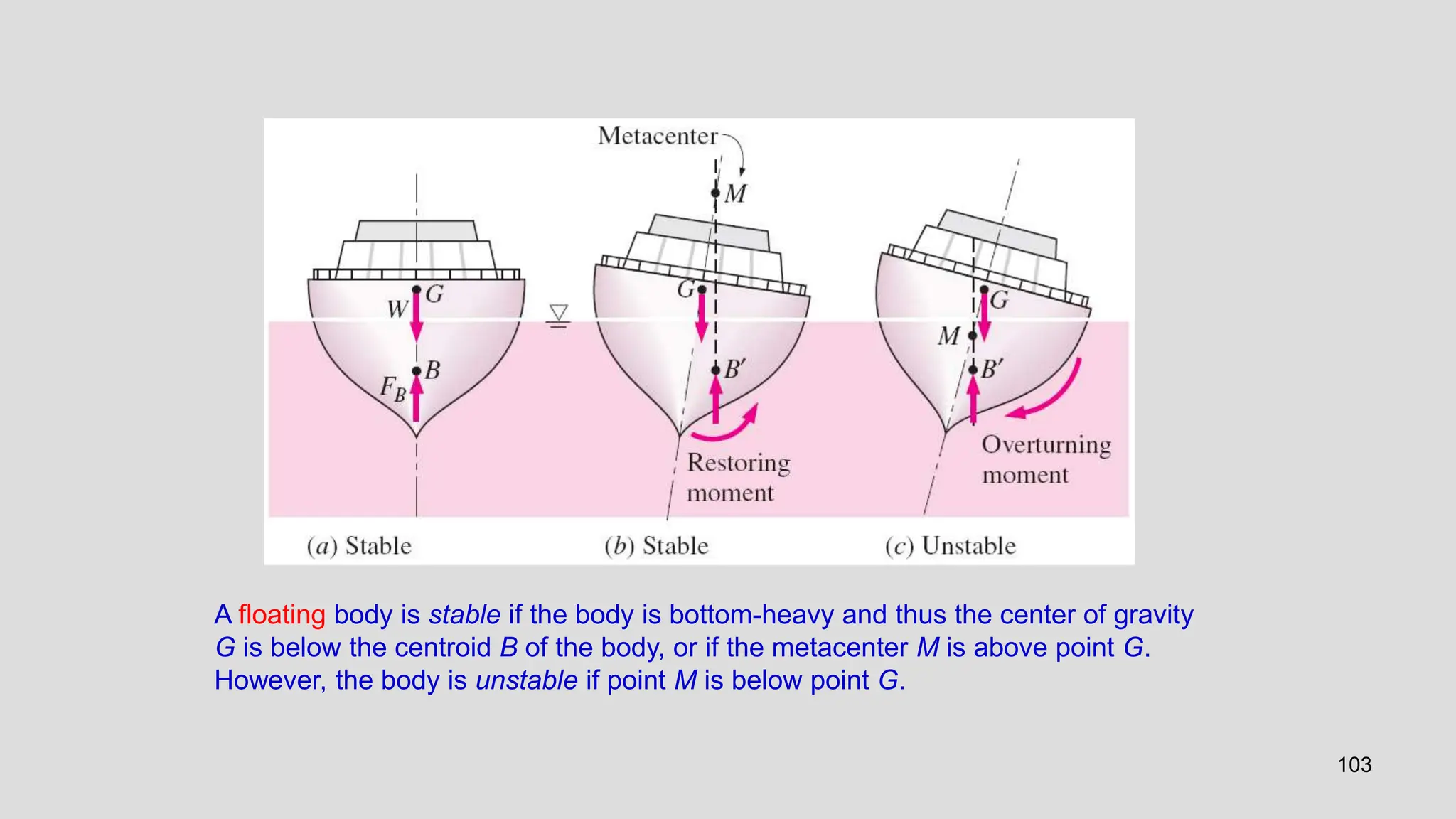

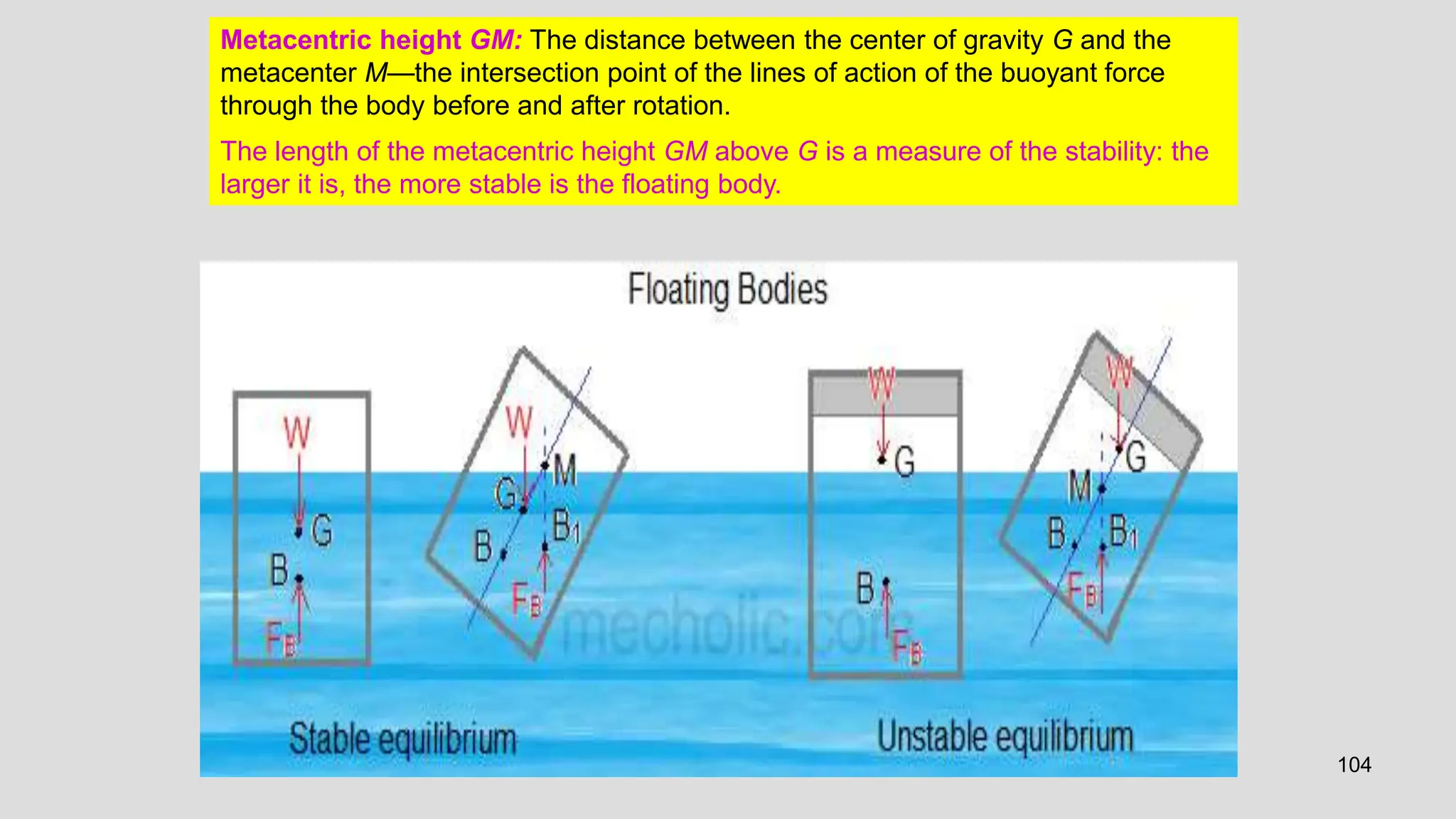

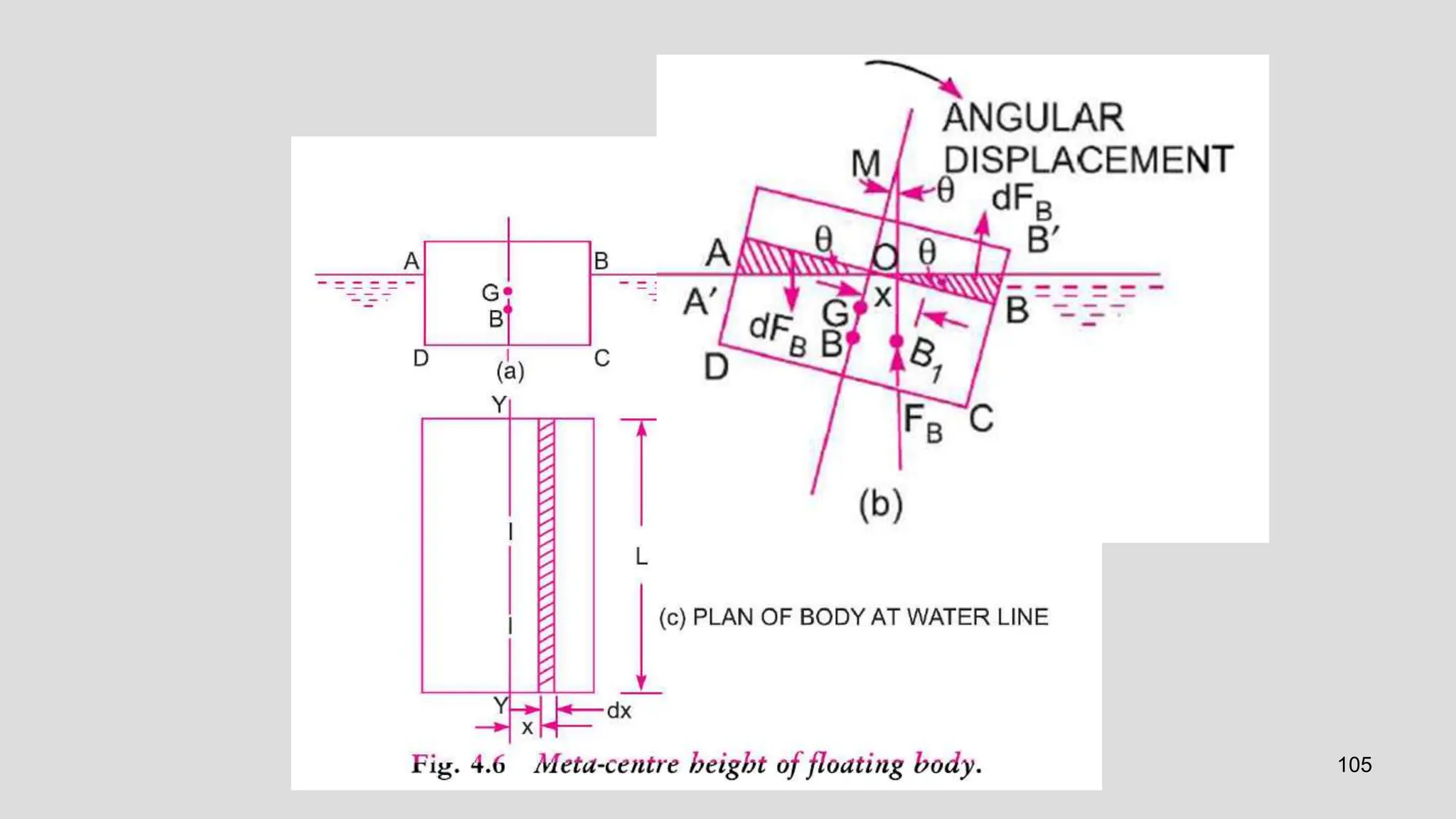

This document covers the properties of fluids, focusing on fluid statics, pressure measurement, density, viscosity, and surface tension. It discusses intensive vs extensive properties, the continuum assumption, drag force, and fluid behavior under shear stress, detailing Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids. Additionally, it explains buoyancy, Archimedes' principle, hydrostatic forces on submerged surfaces, and stability analysis of floating bodies.

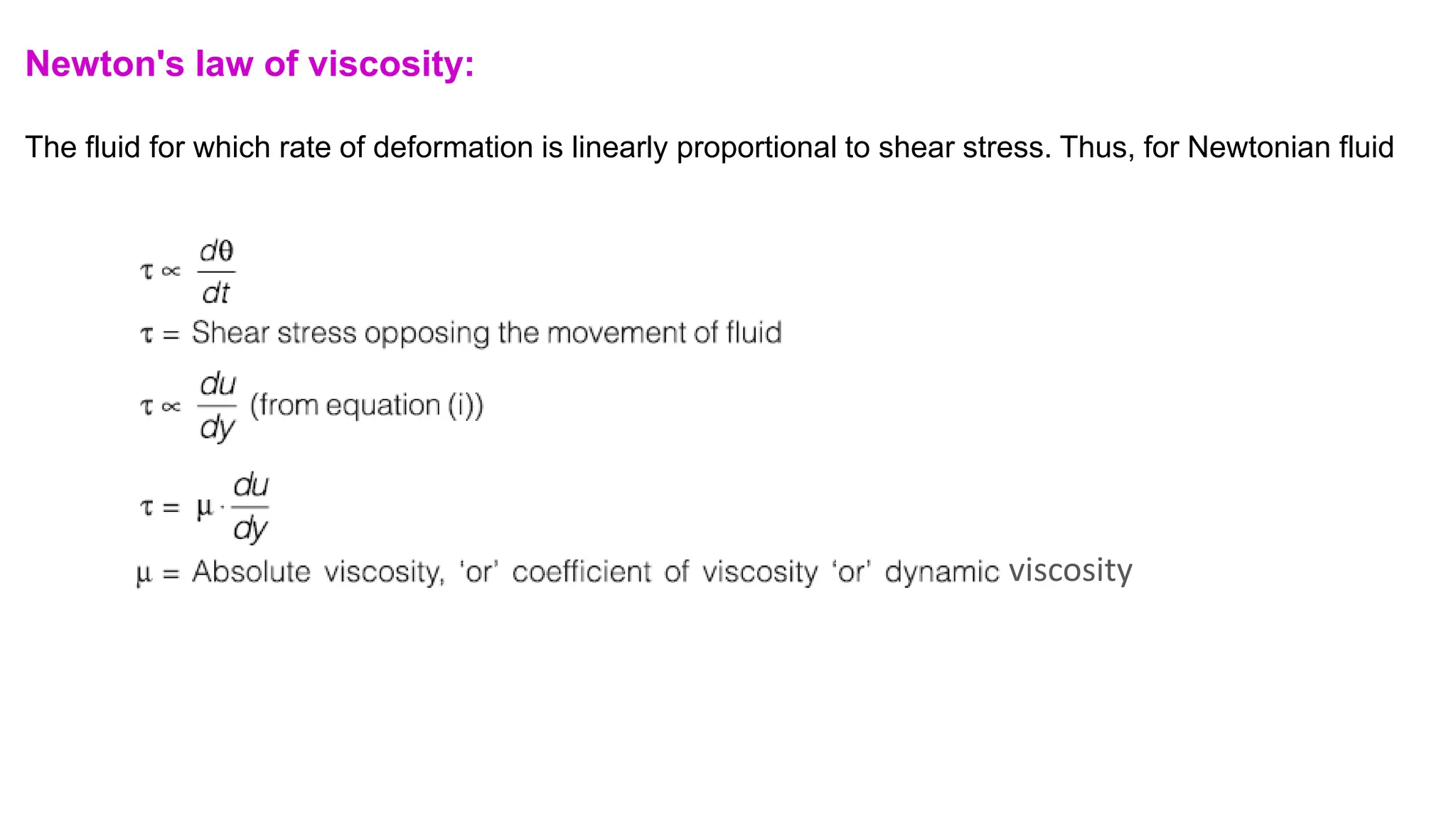

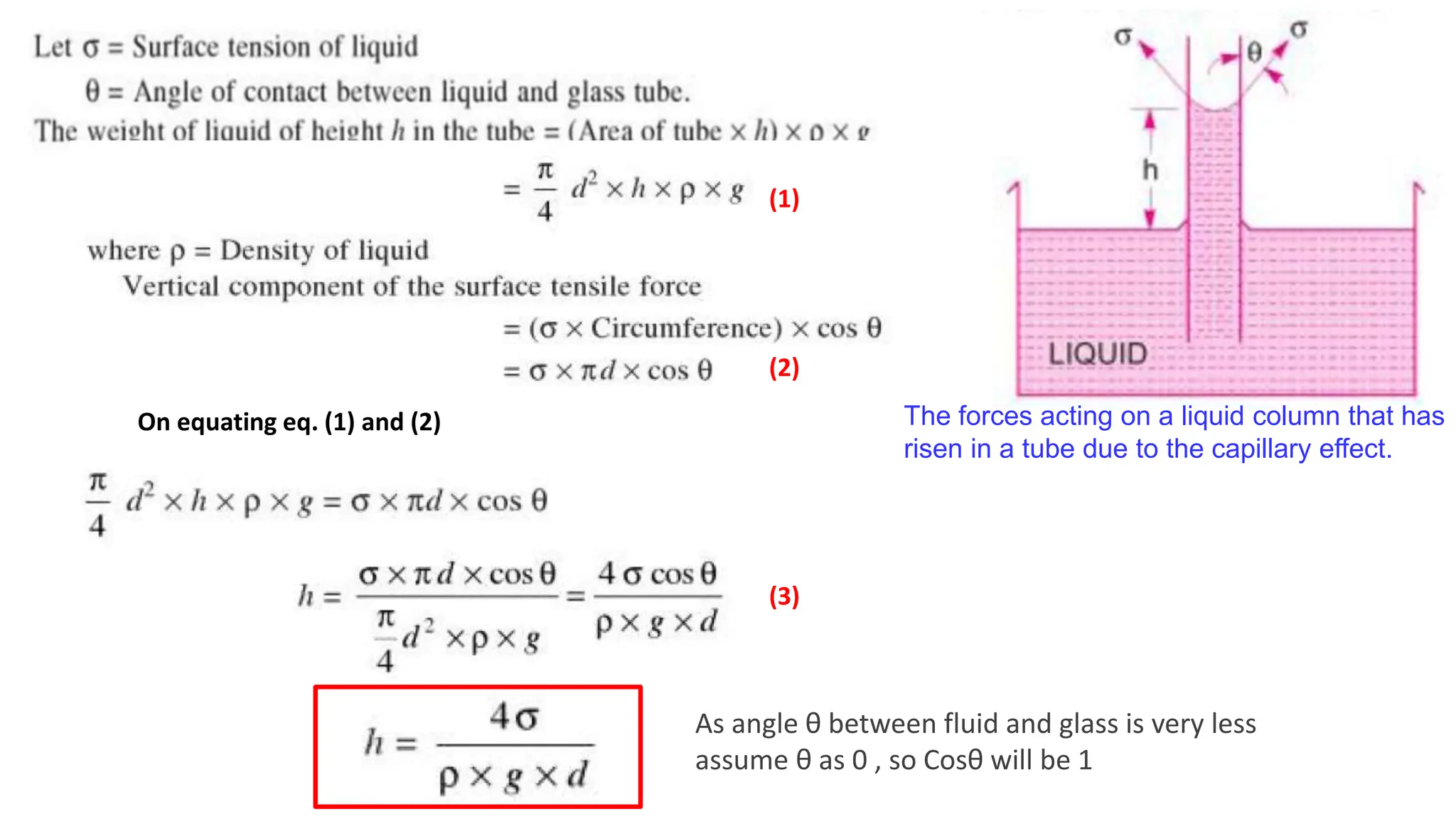

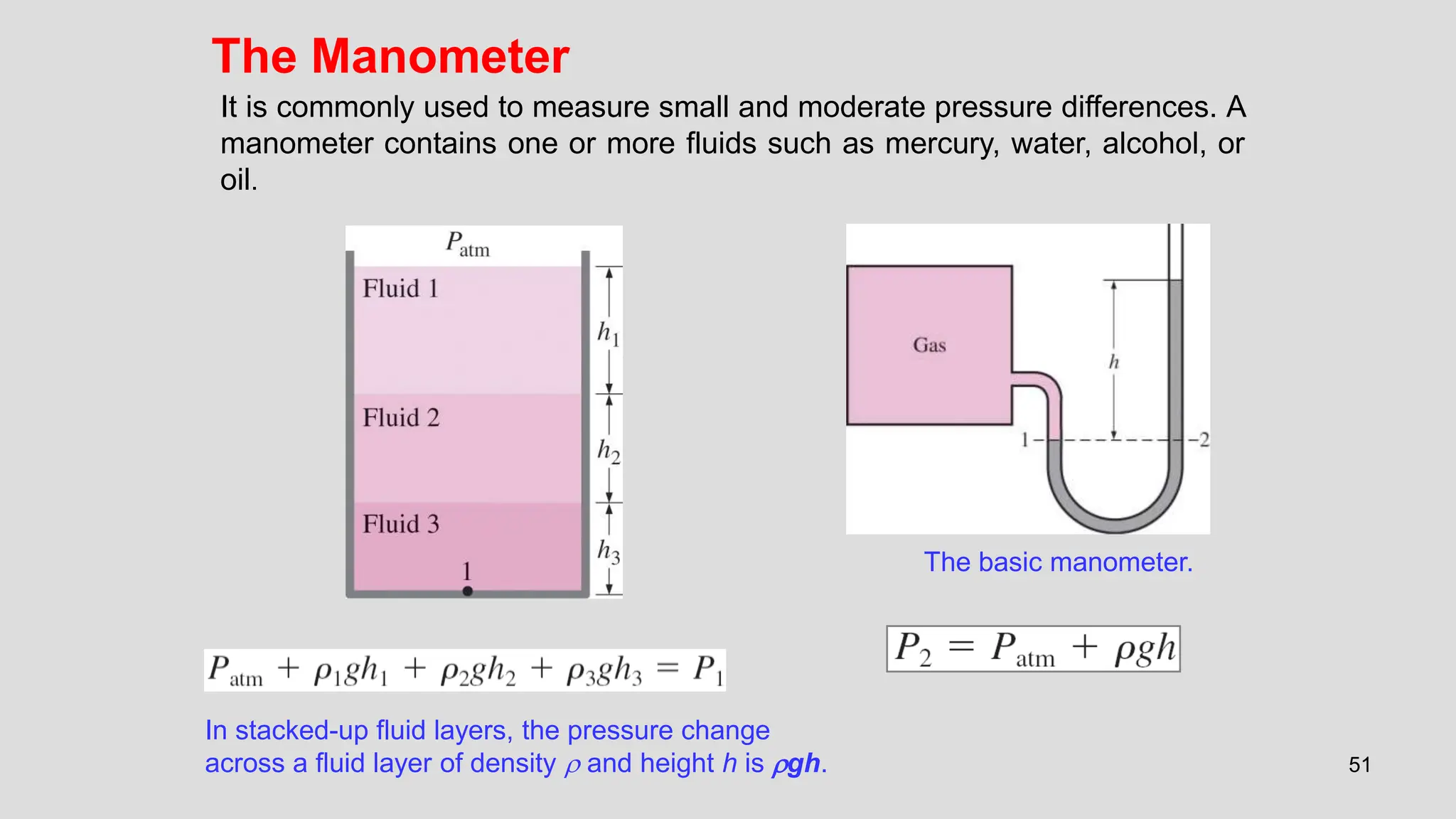

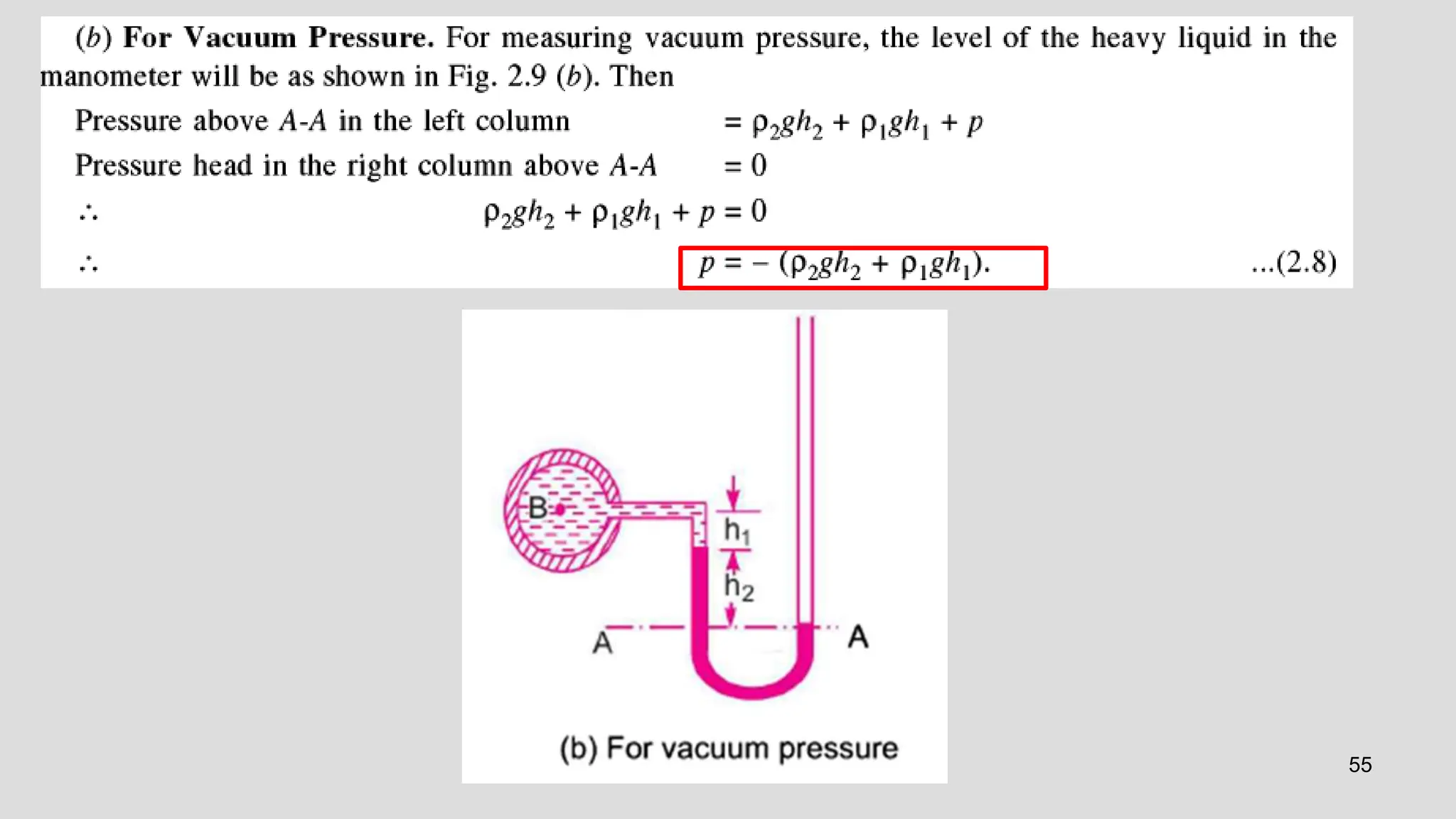

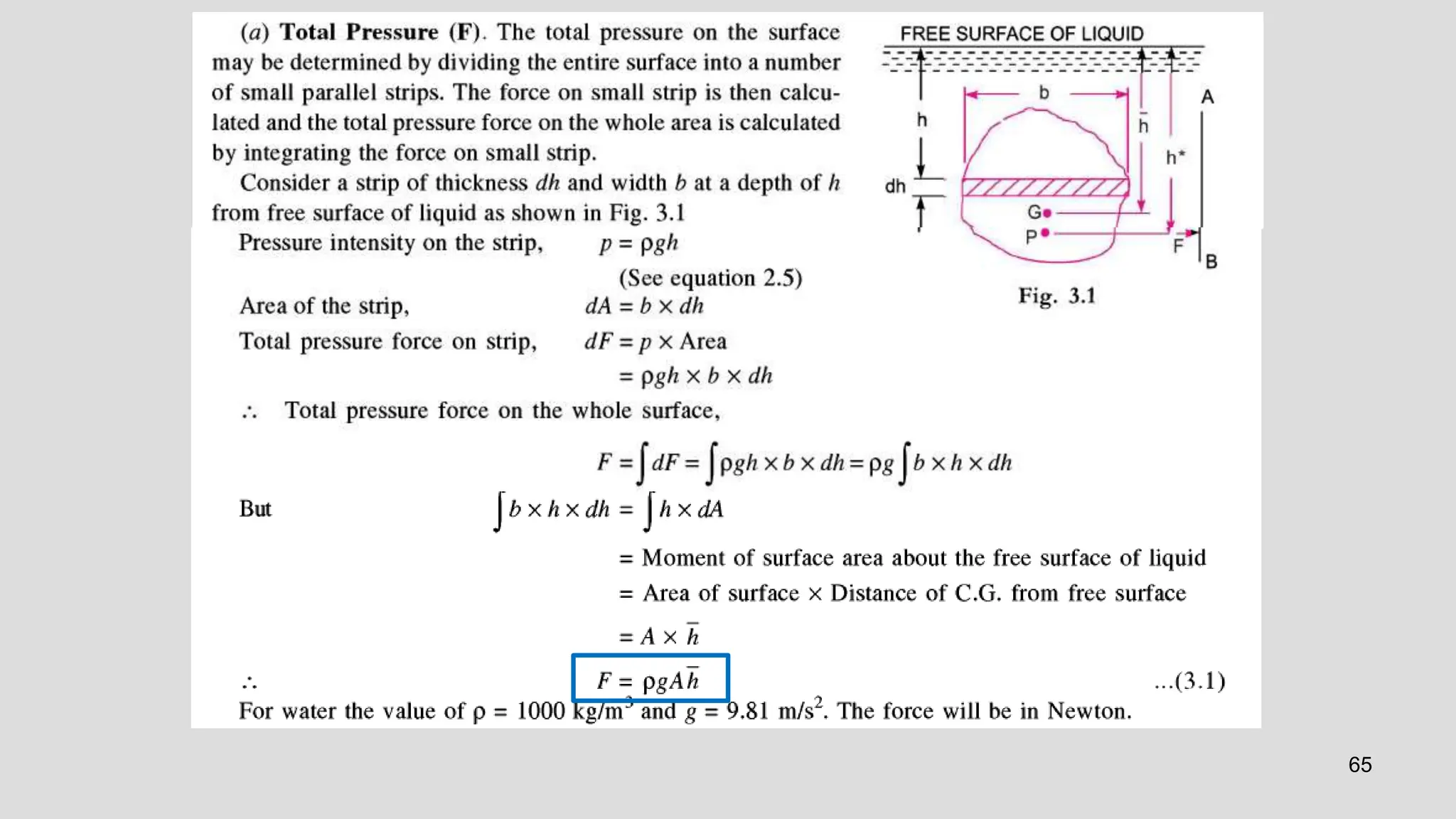

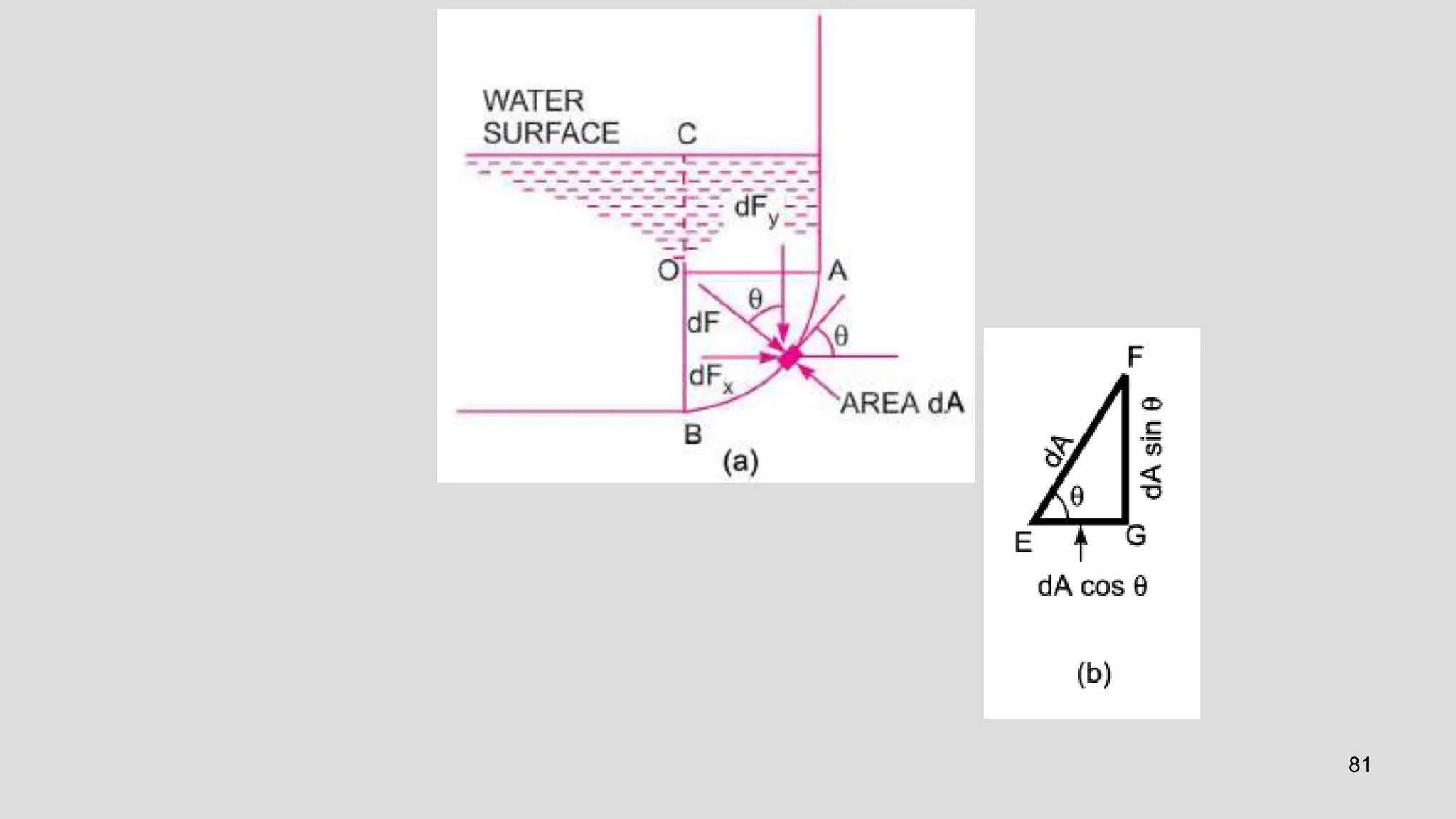

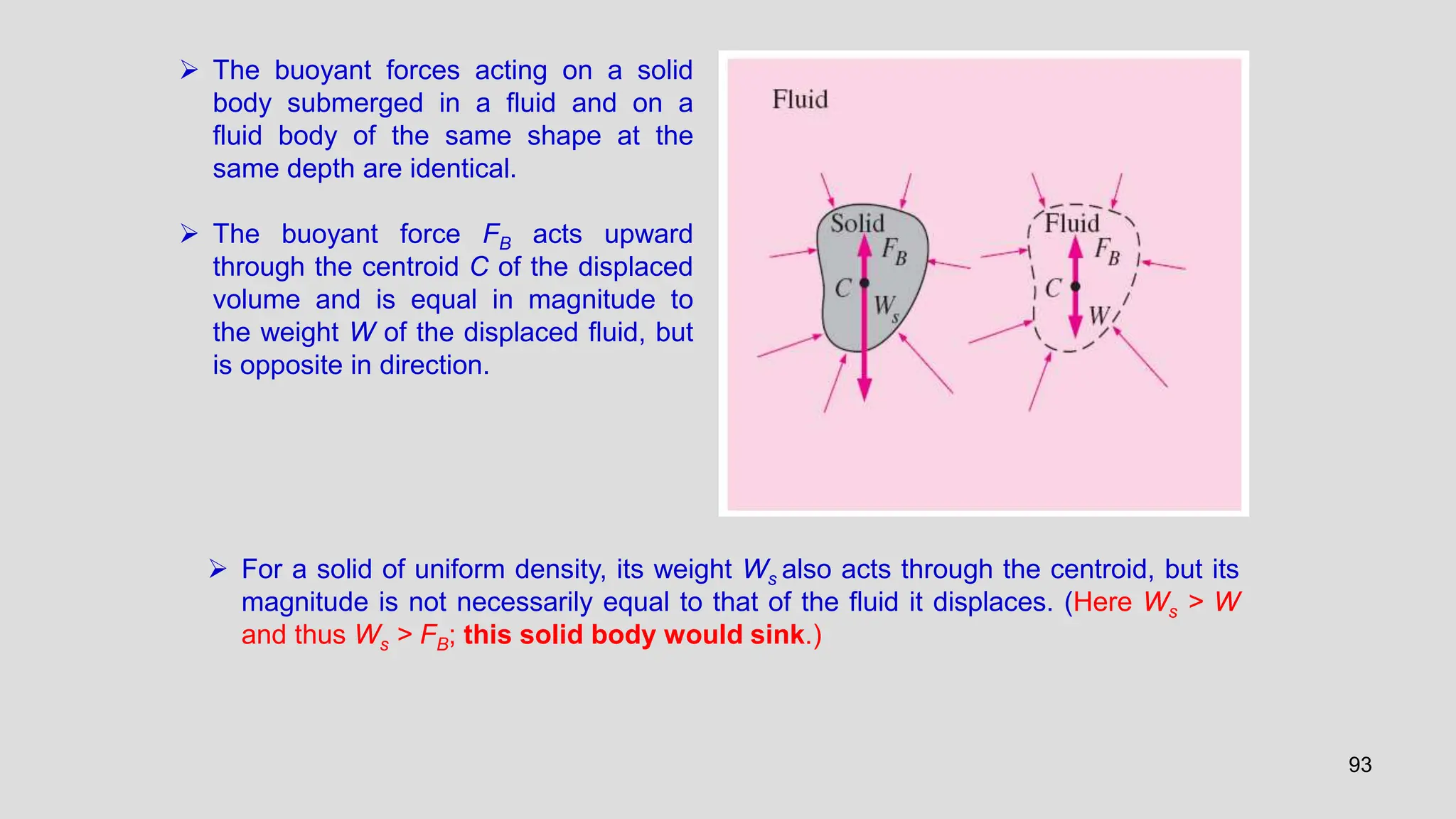

![SURFACE TENSION

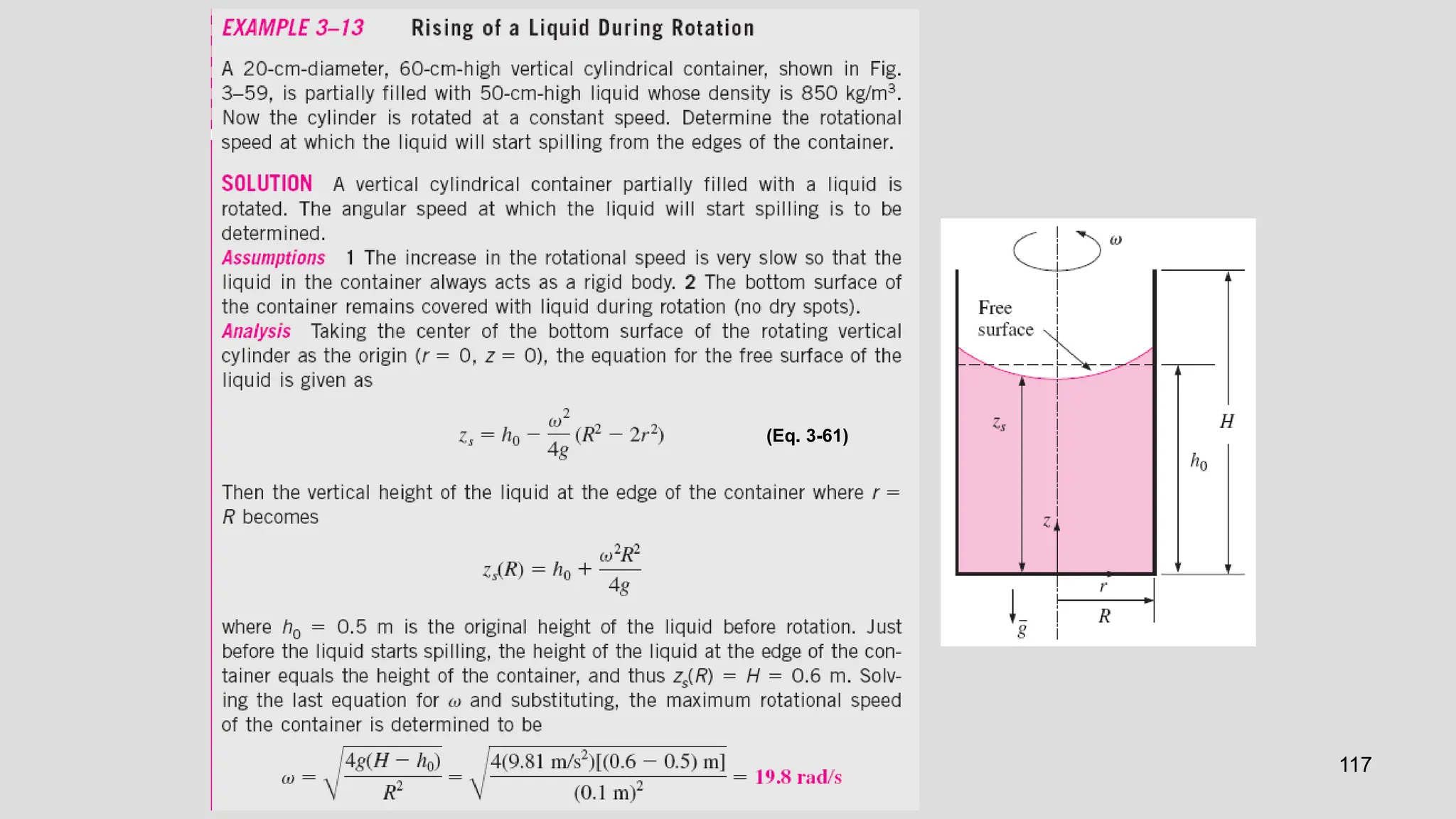

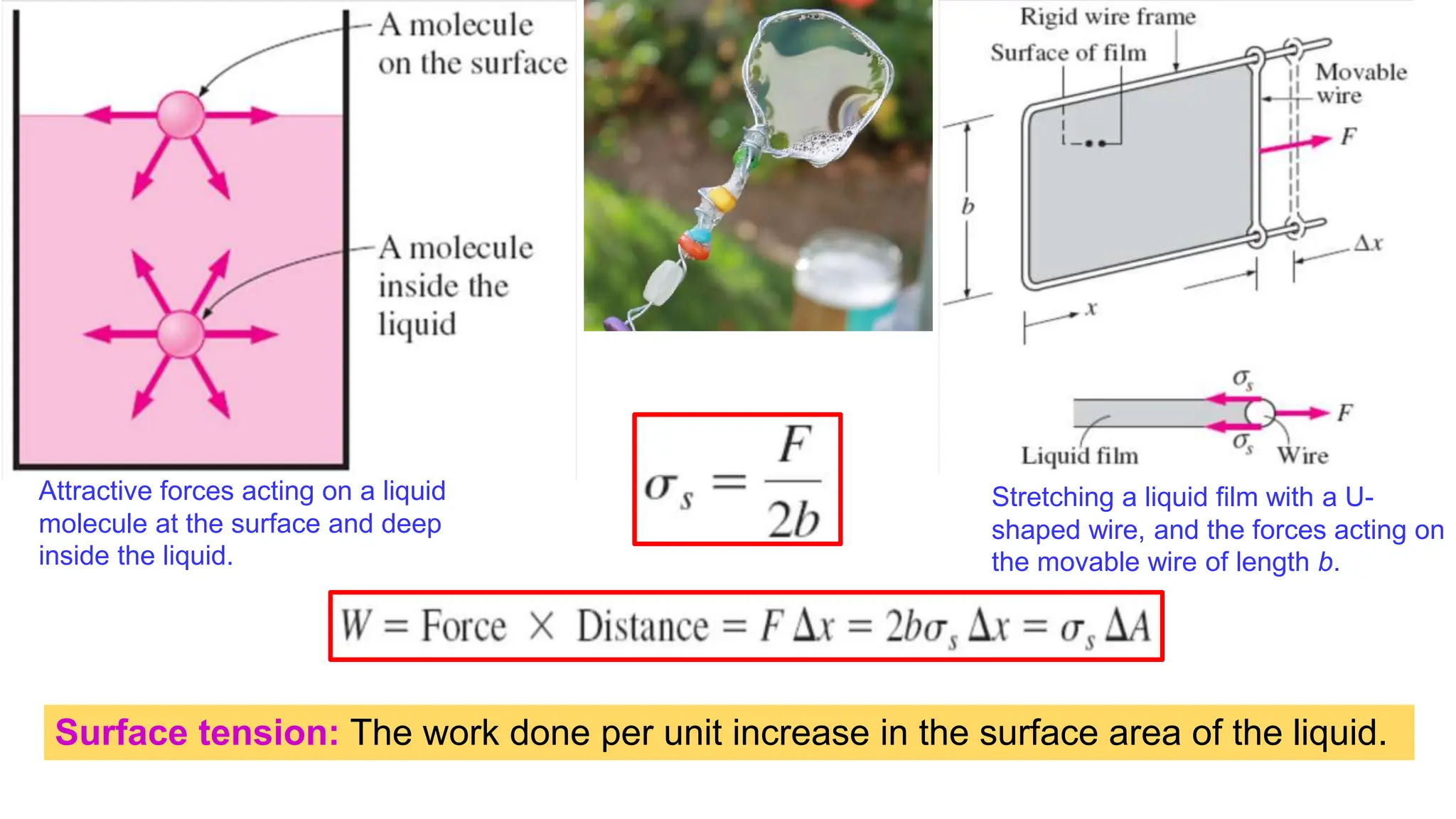

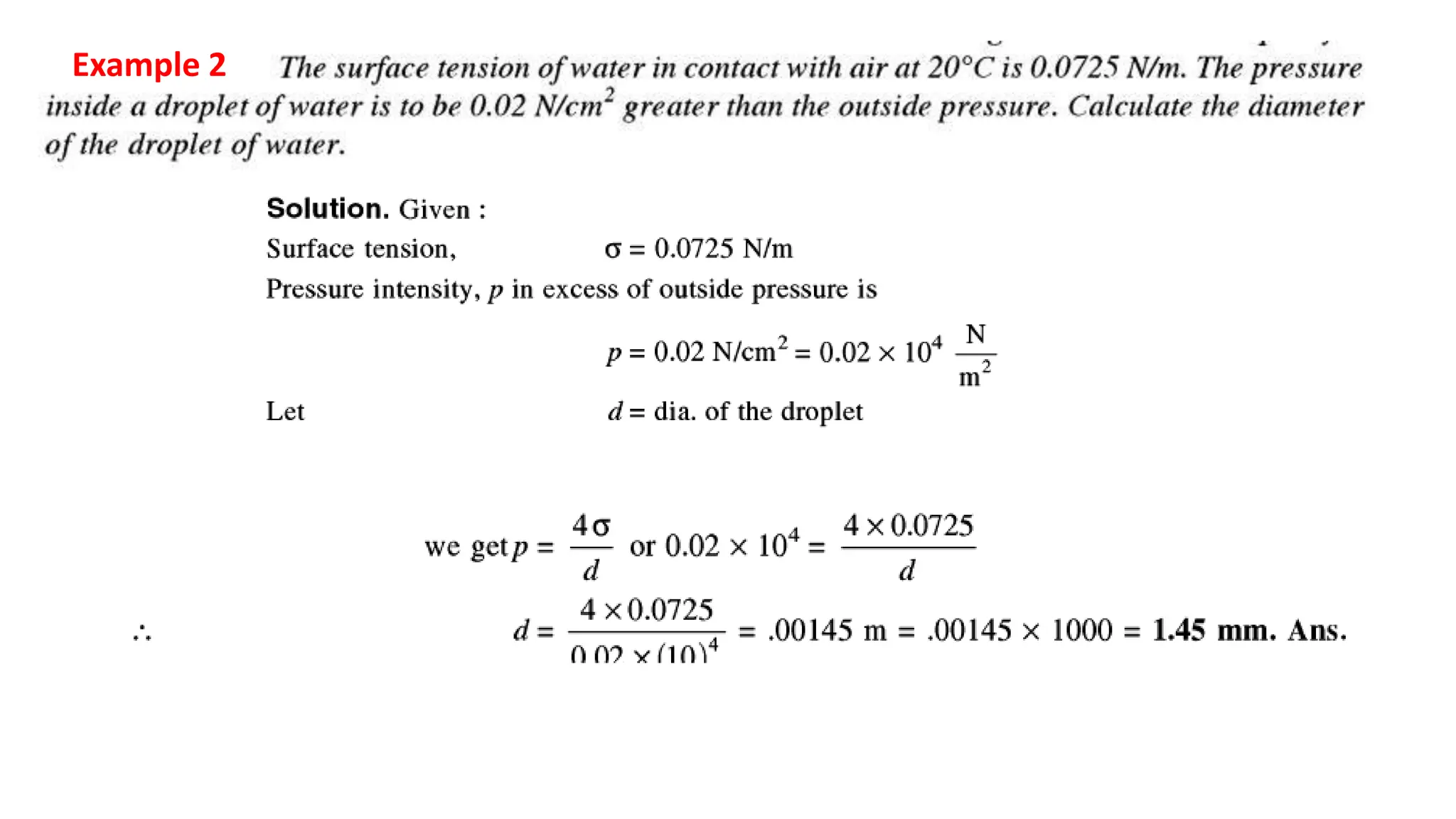

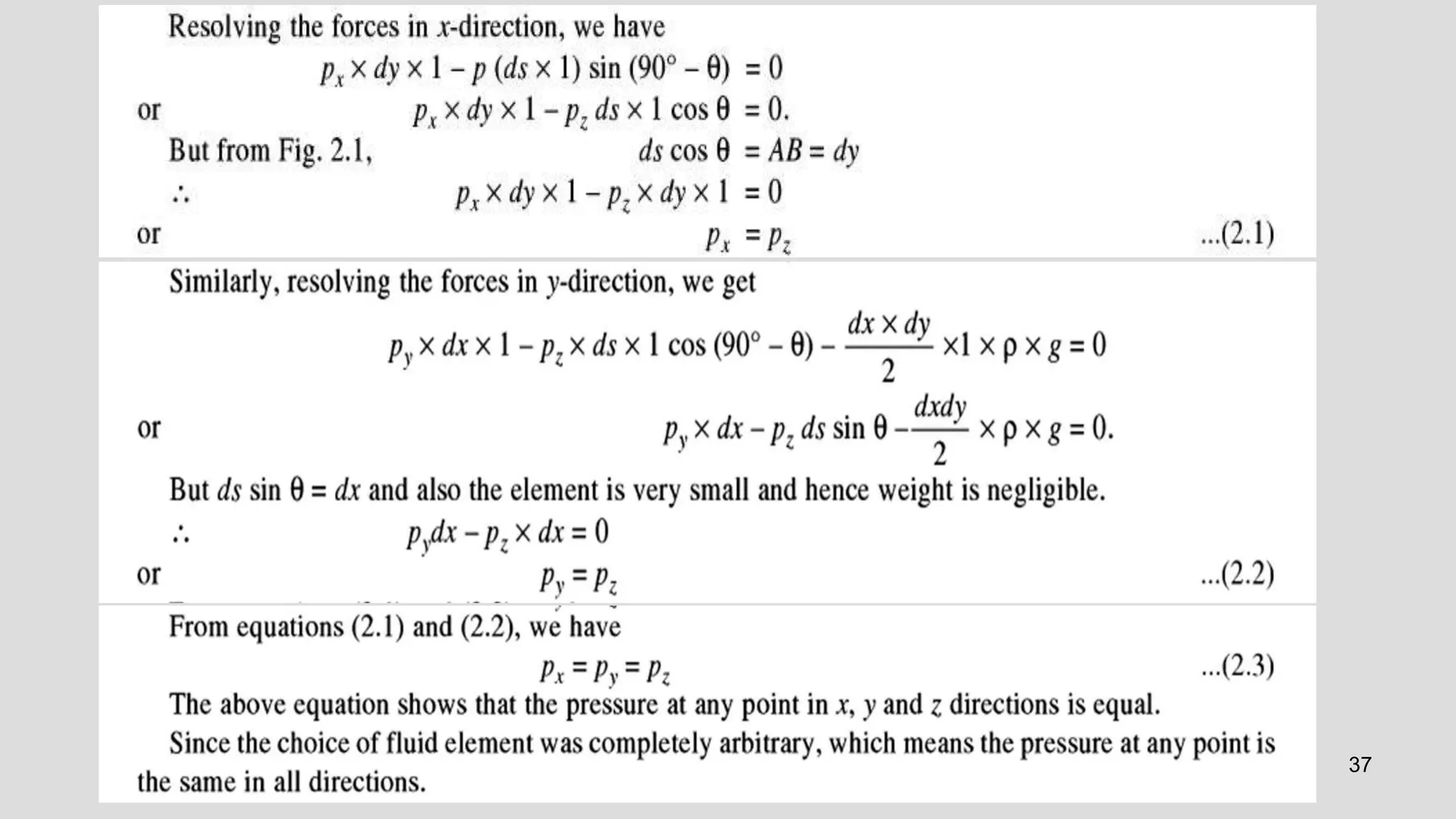

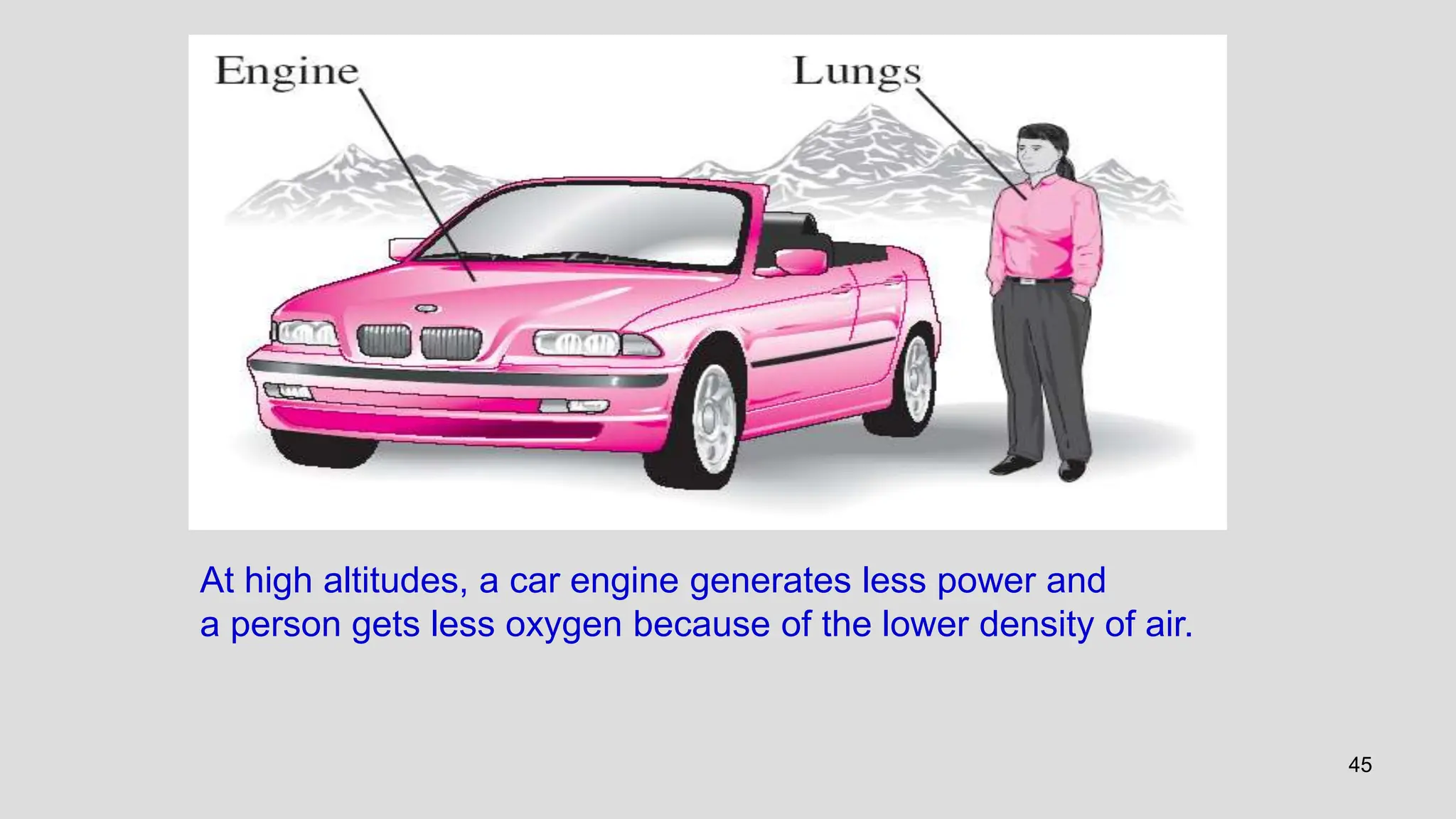

• Liquid droplets behave like small balloons filled

with the liquid on a solid surface, and the surface

of the liquid acts like a stretched elastic

membrane under tension.

• The pulling force that causes this tension acts

parallel to the surface and is due to the attractive

forces between the molecules of the liquid.

• The magnitude of this force per unit length is

called surface tension (or coefficient of surface

tension) and is usually expressed in the unit N/m.

• This effect is also called surface energy [per unit

area] and is expressed in the equivalent unit of

N.m/m2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit1fm-240617160839-927f971f/75/Properties-of-Fluids-Fluid-Statics-Pressure-Measurement-19-2048.jpg)

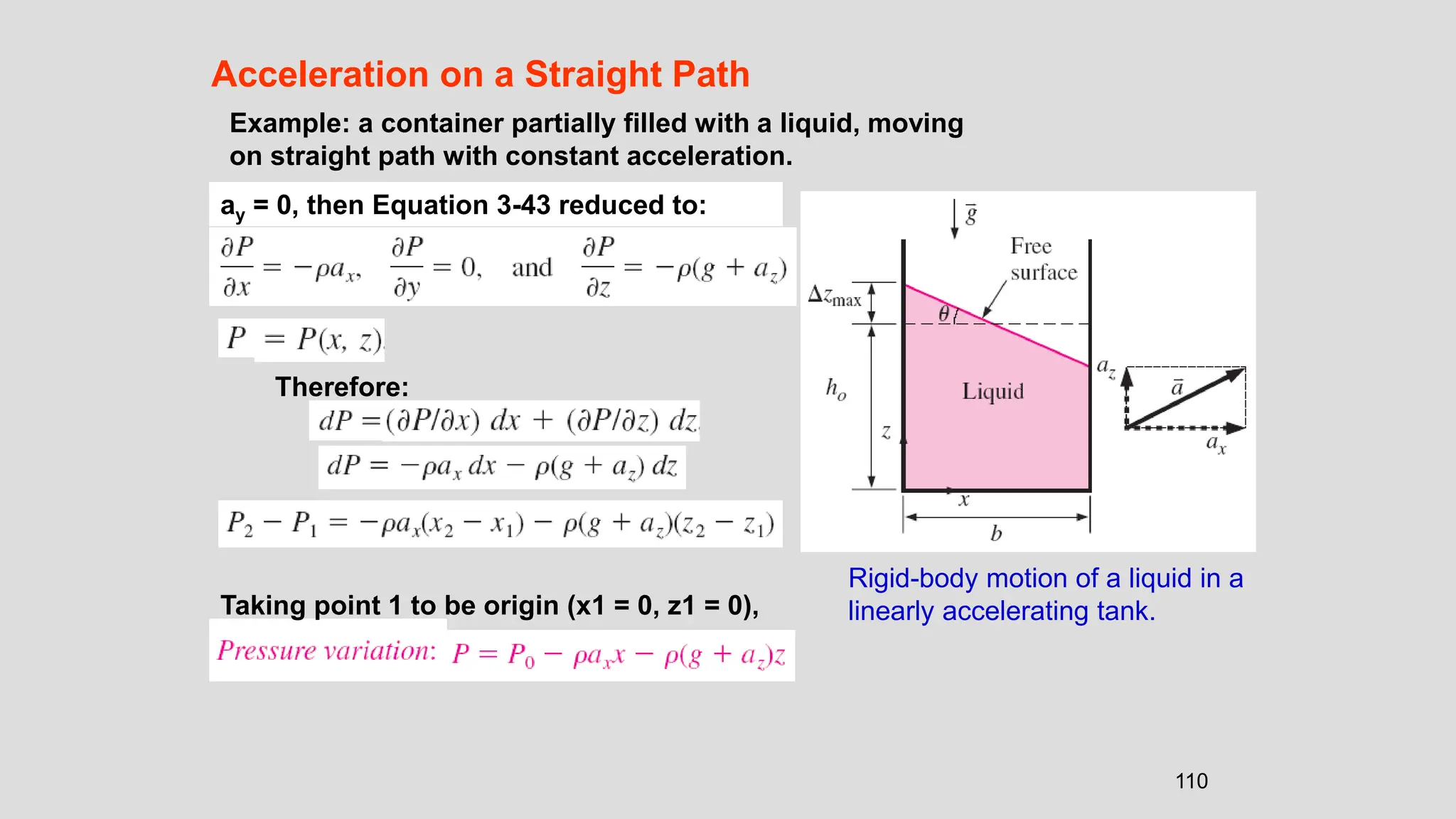

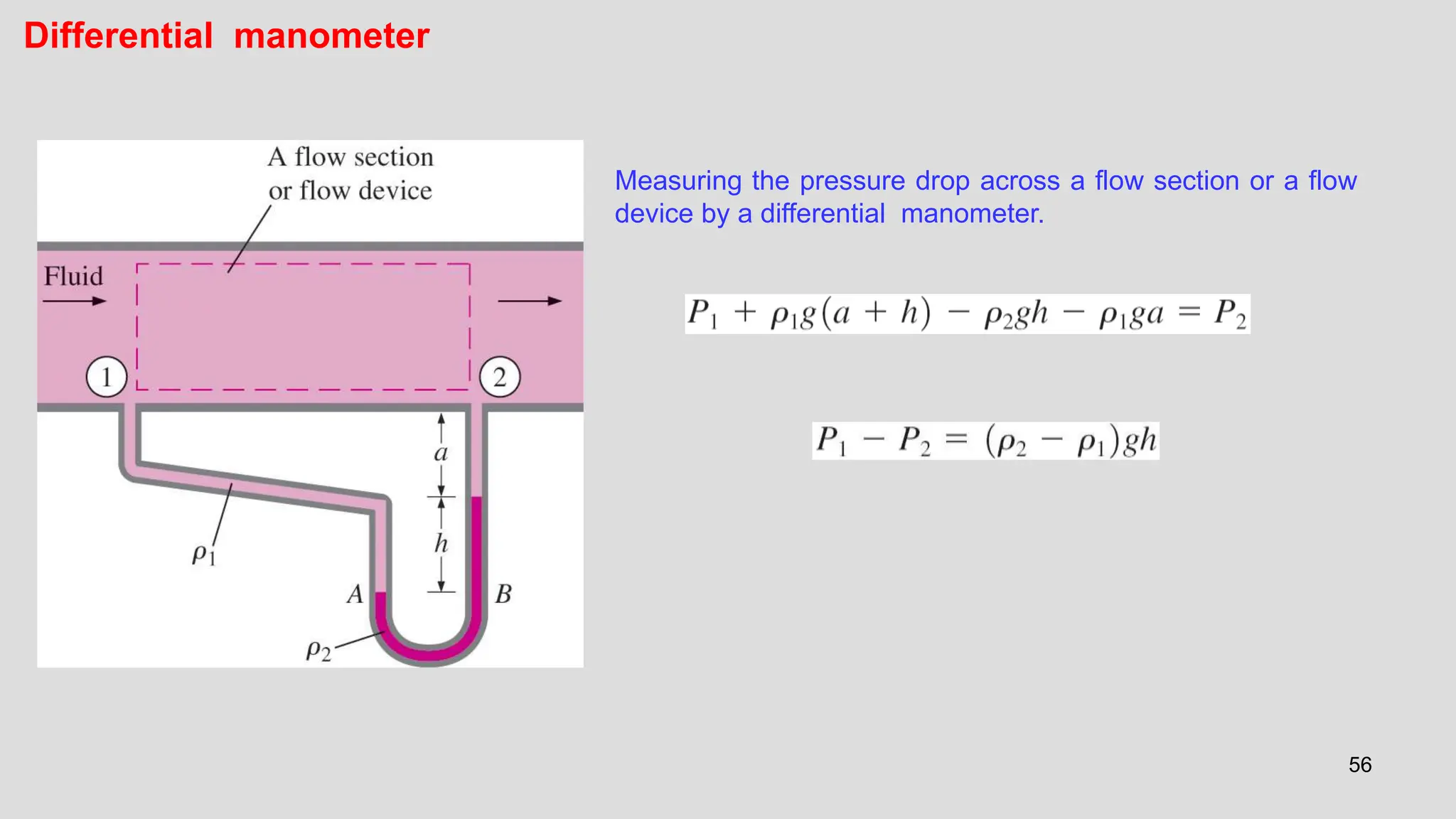

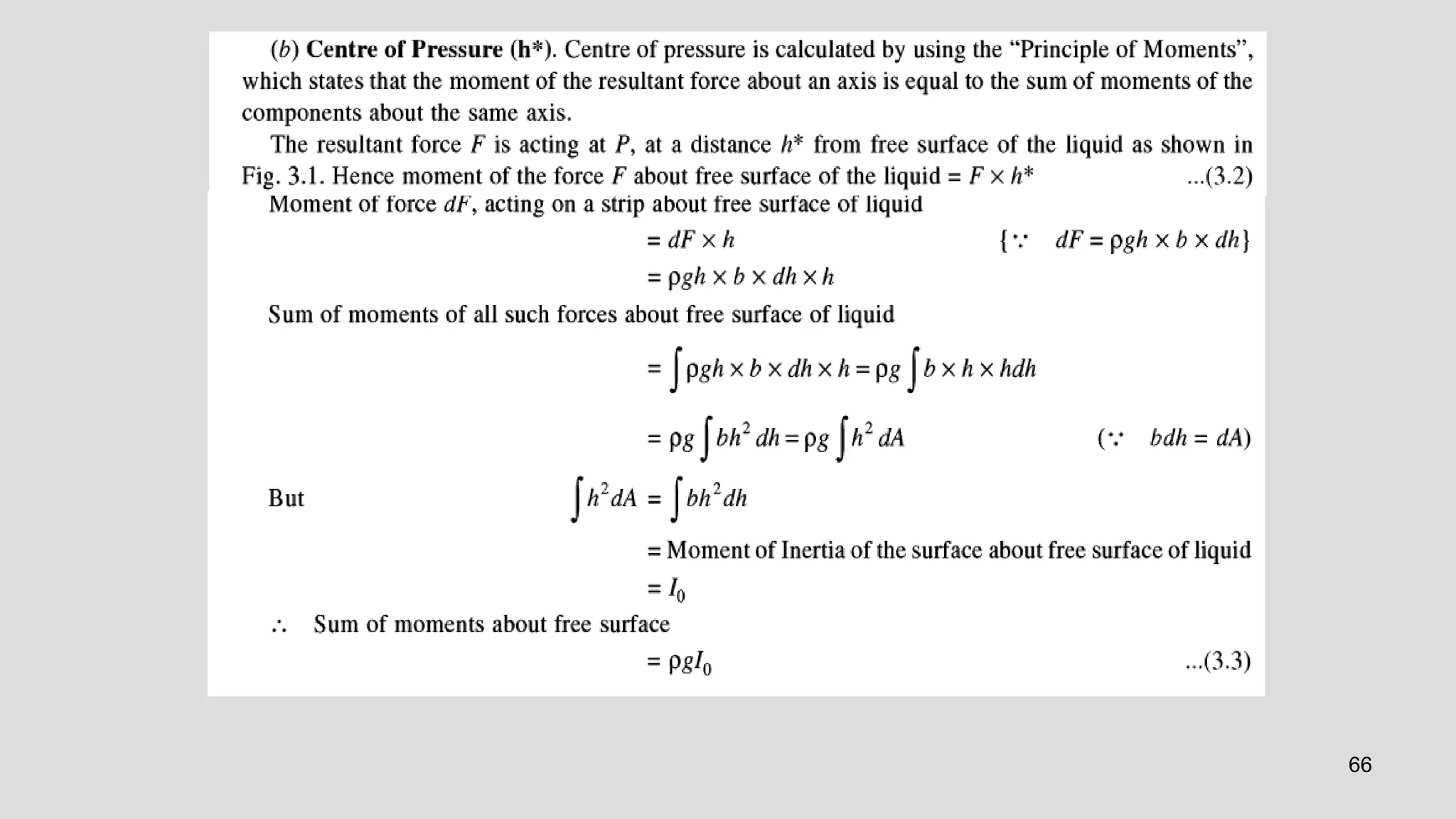

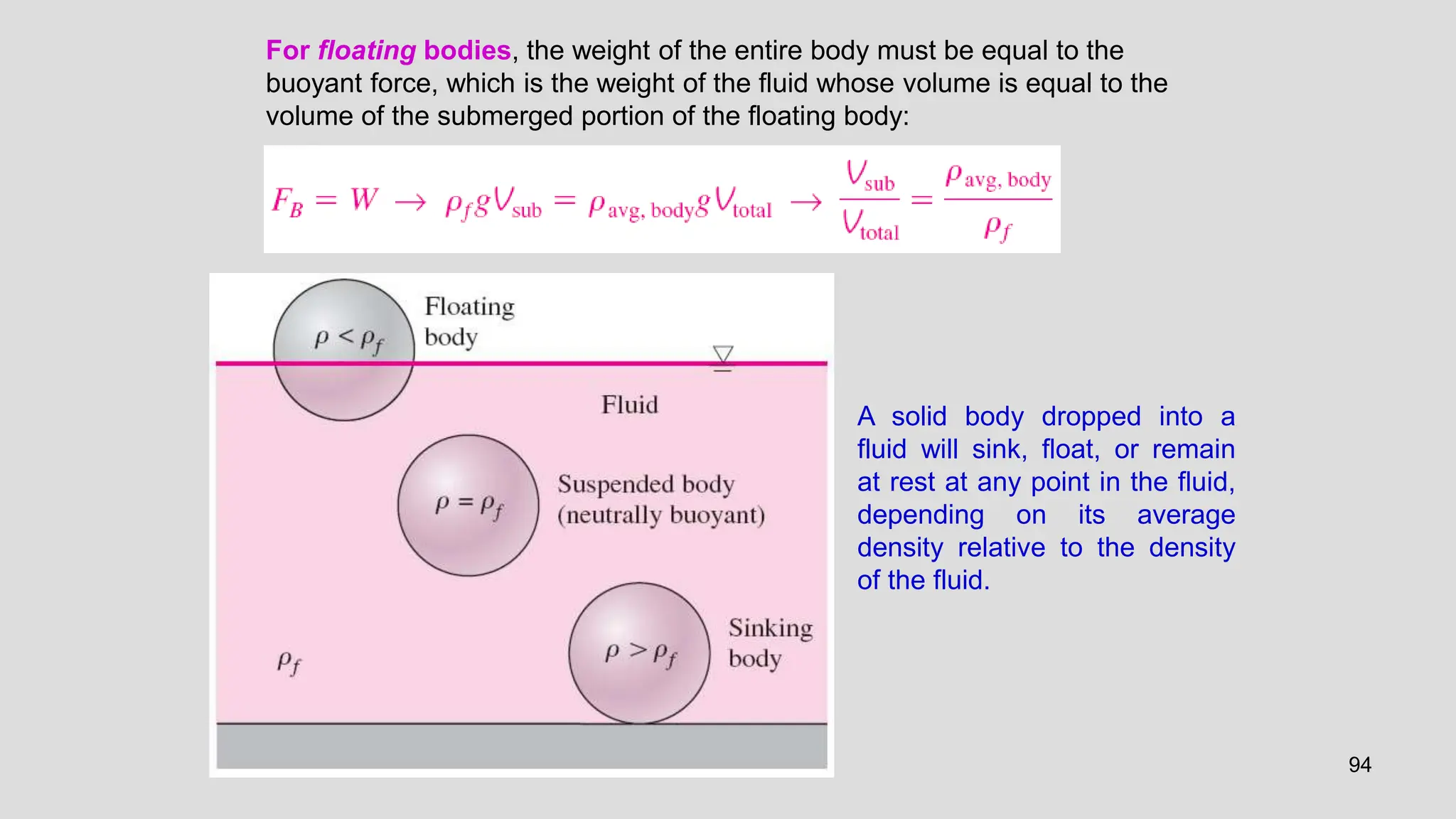

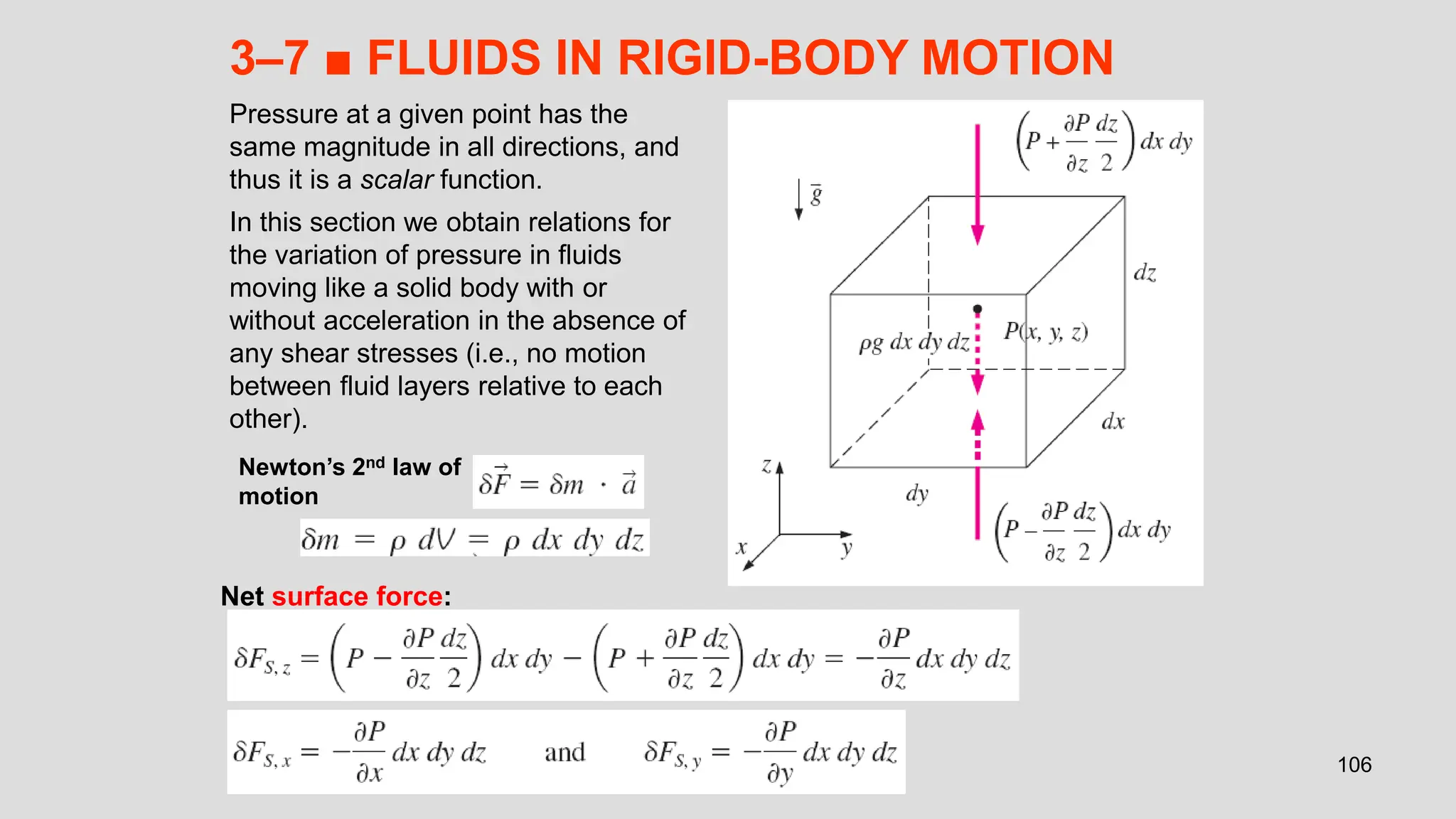

![108

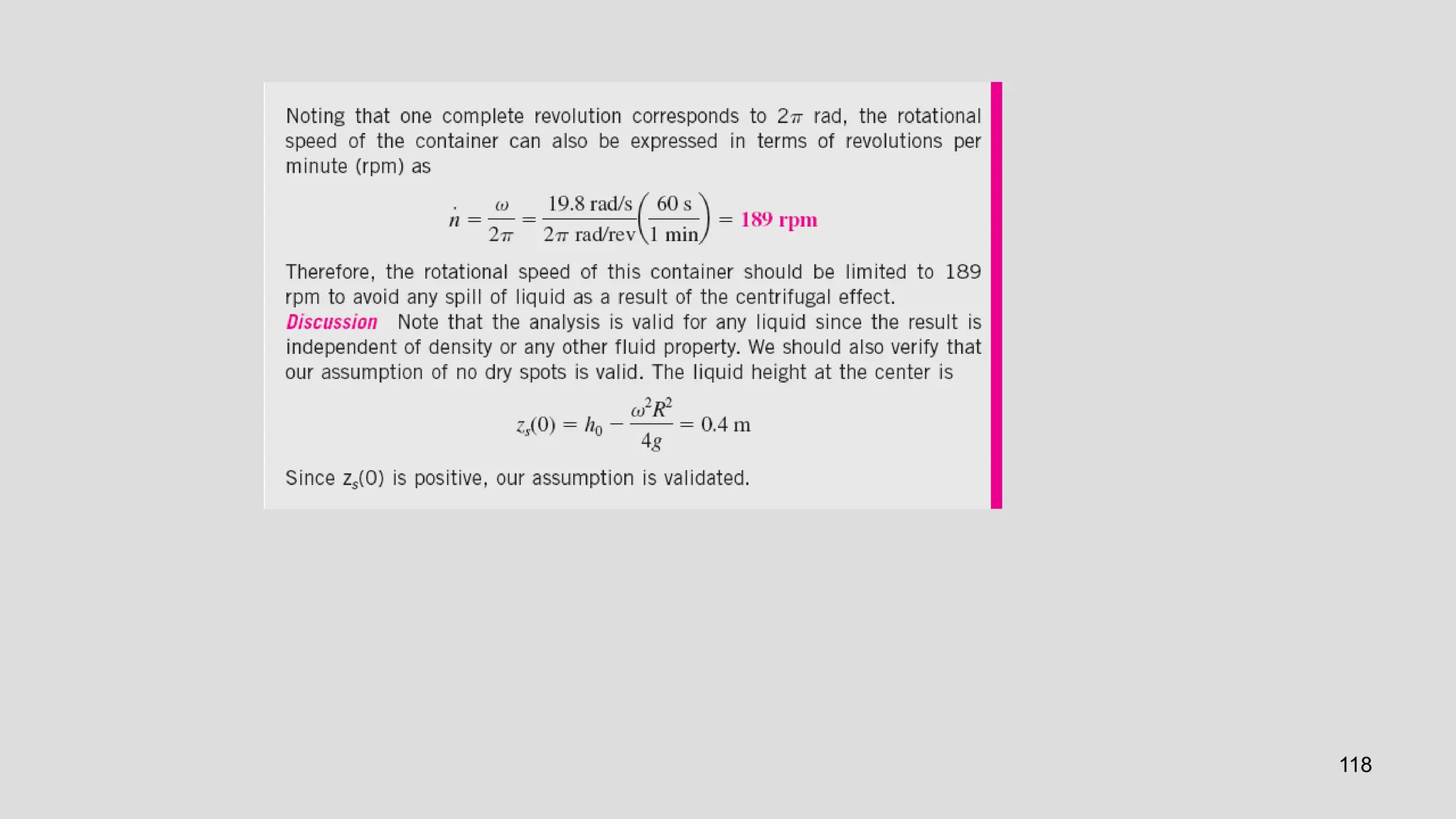

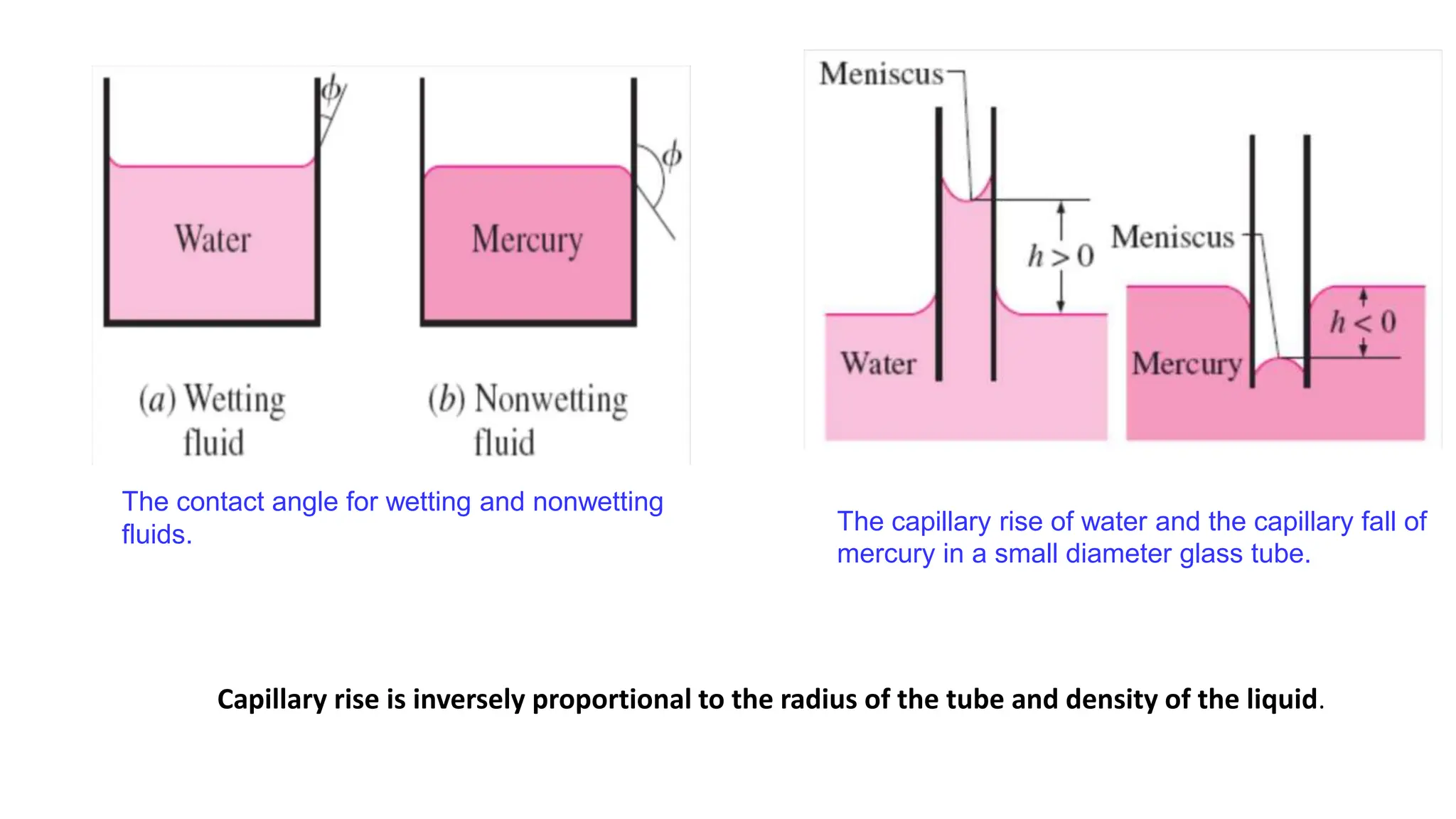

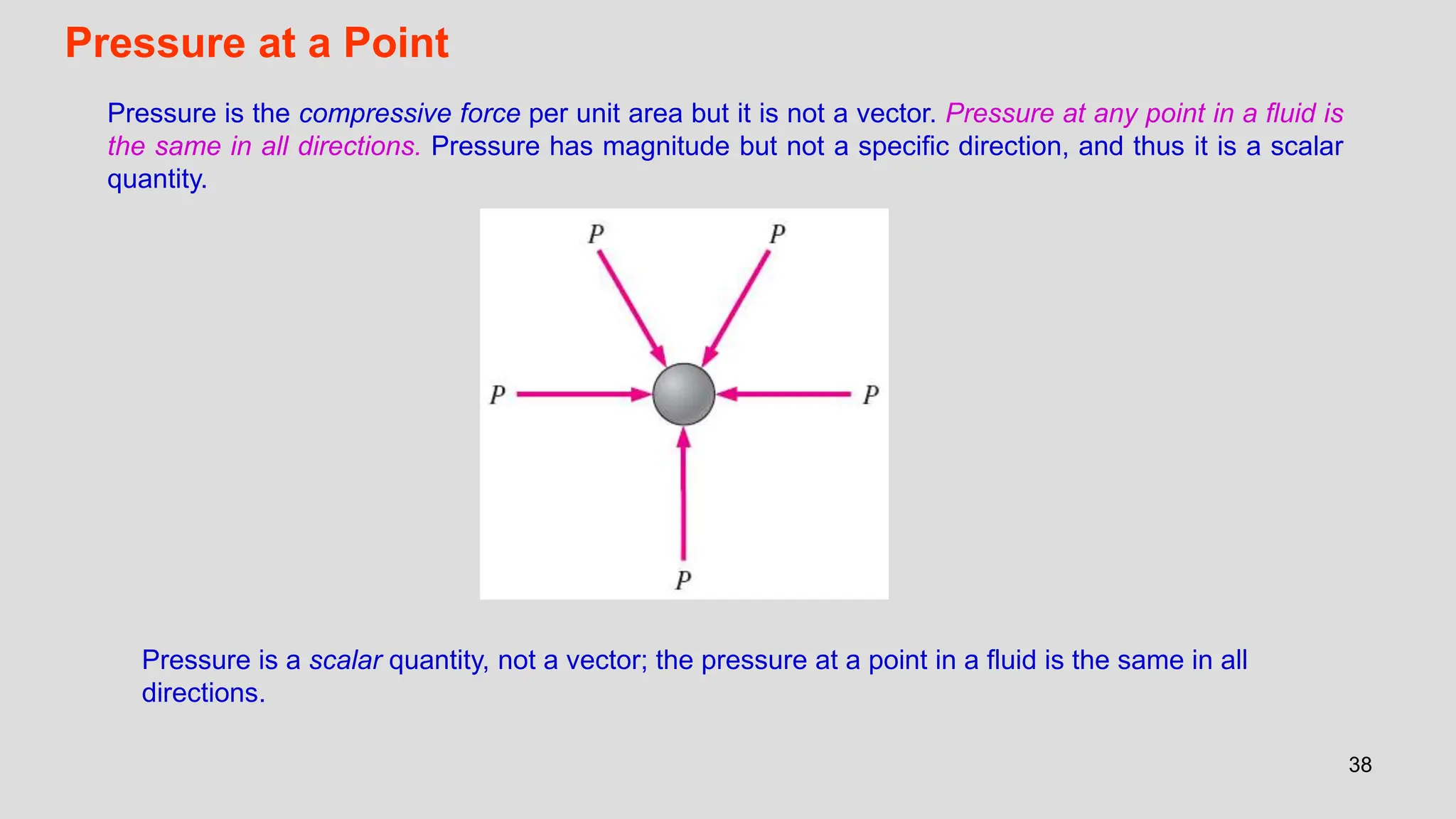

Special Case 1: Fluids at Rest

For fluids at rest or moving on a straight path at constant velocity, all

components of acceleration are zero, and the relations reduce to

The pressure remains constant in any horizontal direction (P is

independent of x and y) and varies only in the vertical direction as

a result of gravity [and thus P = P(z)]. These relations are

applicable for both compressible and incompressible fluids.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit1fm-240617160839-927f971f/75/Properties-of-Fluids-Fluid-Statics-Pressure-Measurement-92-2048.jpg)