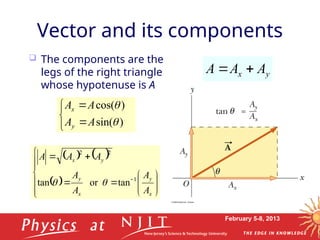

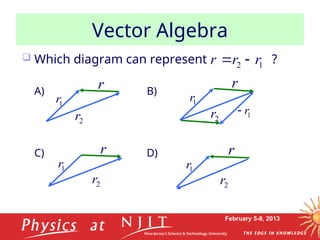

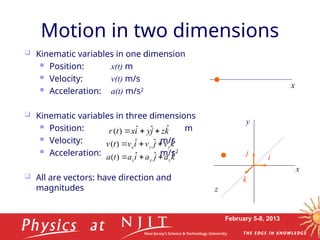

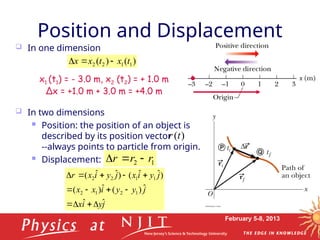

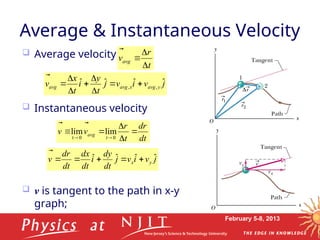

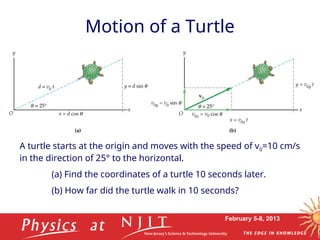

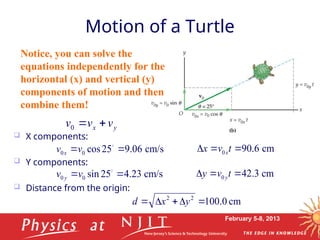

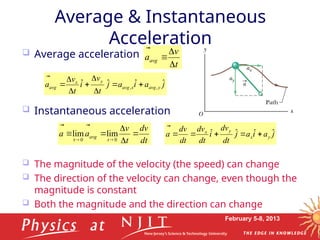

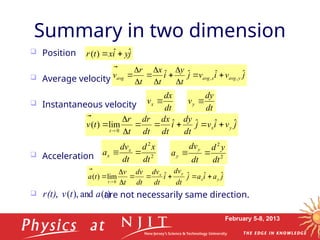

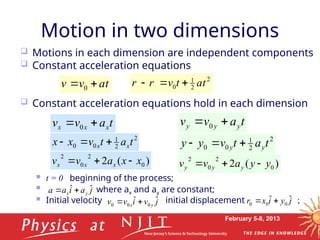

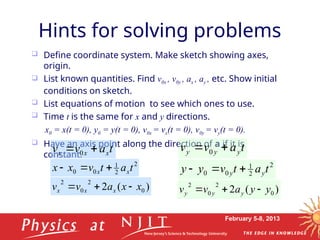

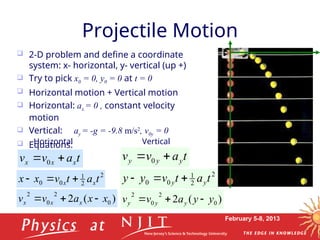

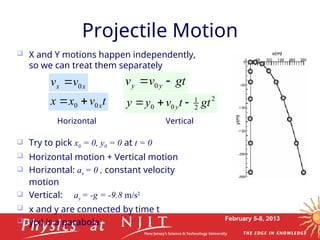

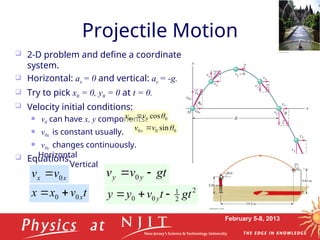

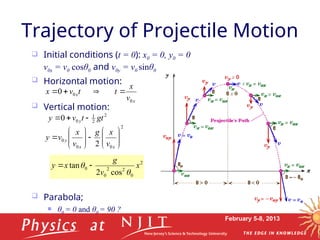

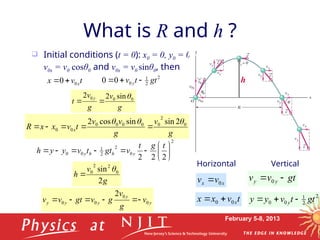

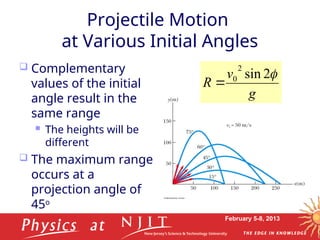

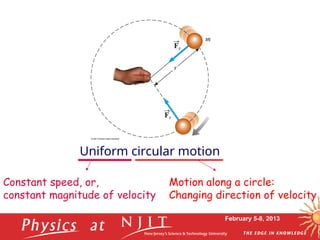

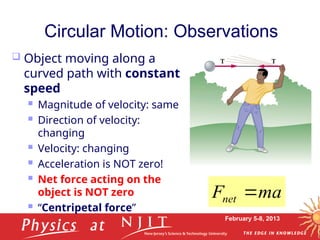

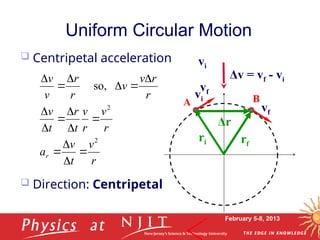

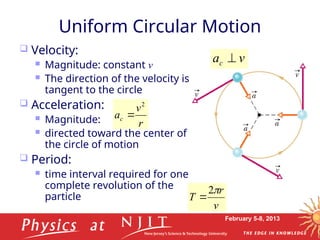

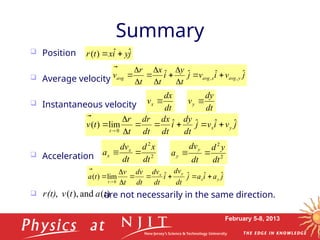

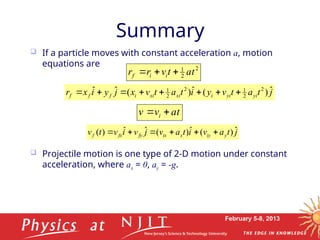

This document covers Lecture 3 of a physics course on mechanics, focusing on motion in two dimensions. Key topics include vectors, vector algebra, projectile motion, uniform circular motion, and relations of average and instantaneous velocity and acceleration. The lecture elaborates on kinematic variables and various equations governing motion in two-dimensional space.