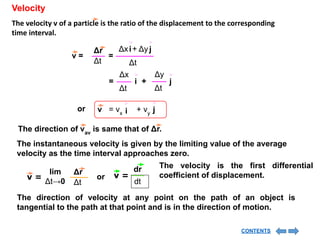

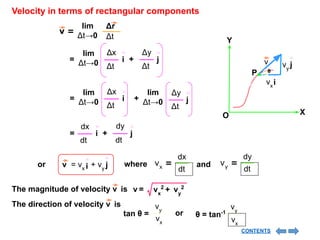

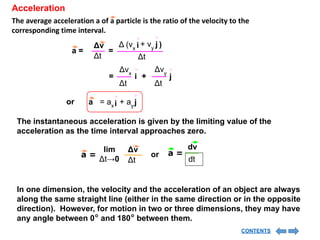

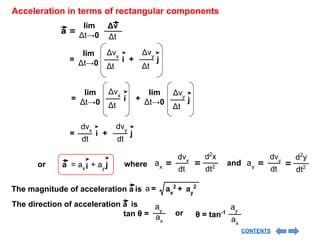

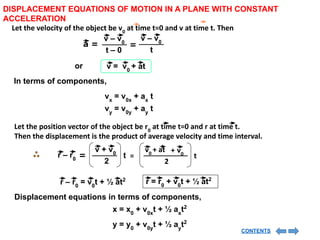

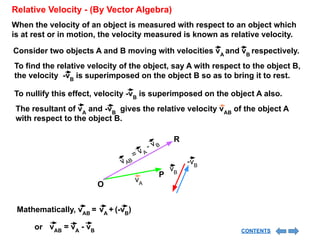

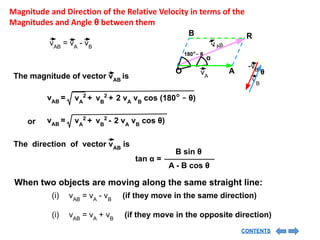

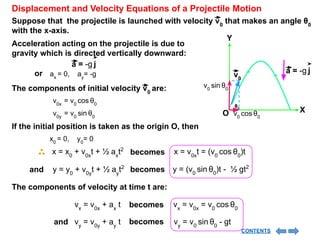

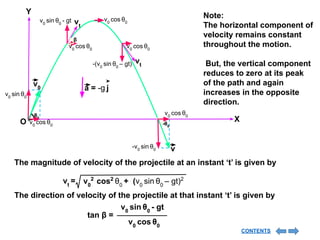

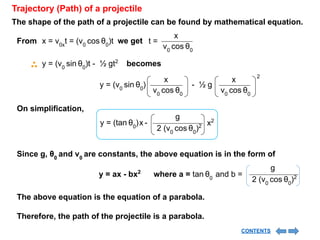

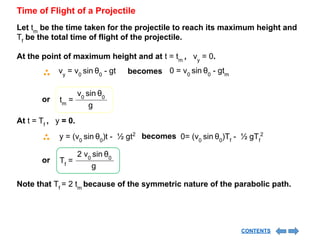

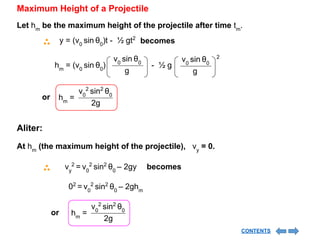

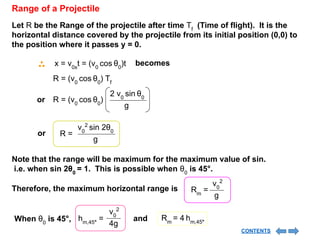

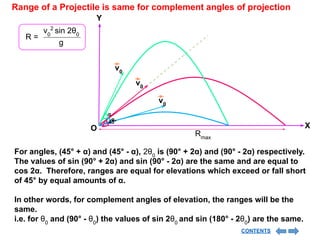

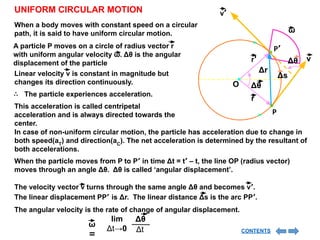

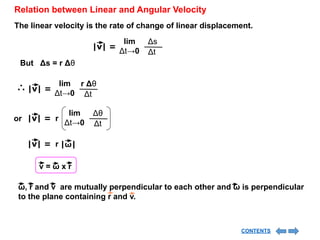

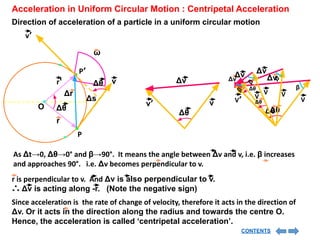

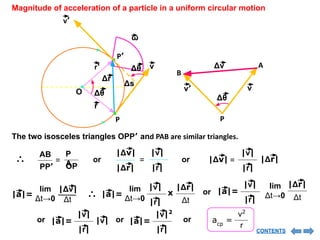

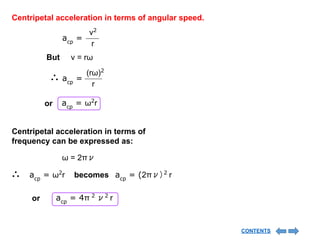

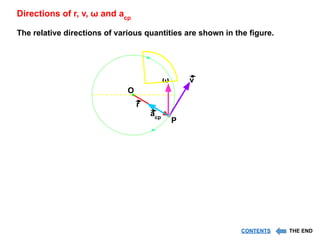

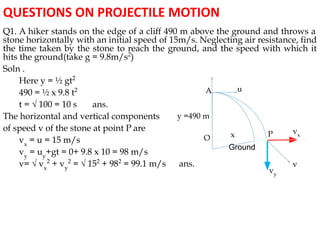

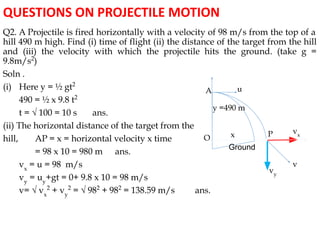

This document discusses motion in a plane and uniform circular motion. It covers topics like position and displacement vectors, velocity, acceleration, projectile motion, and equations of motion with constant acceleration. Projectile motion involves horizontal and vertical components. The trajectory of a projectile is a parabola. Equations are provided for time of flight, maximum height, and range of a projectile. Uniform circular motion requires centripetal acceleration towards the center to maintain a constant speed along the circular path.