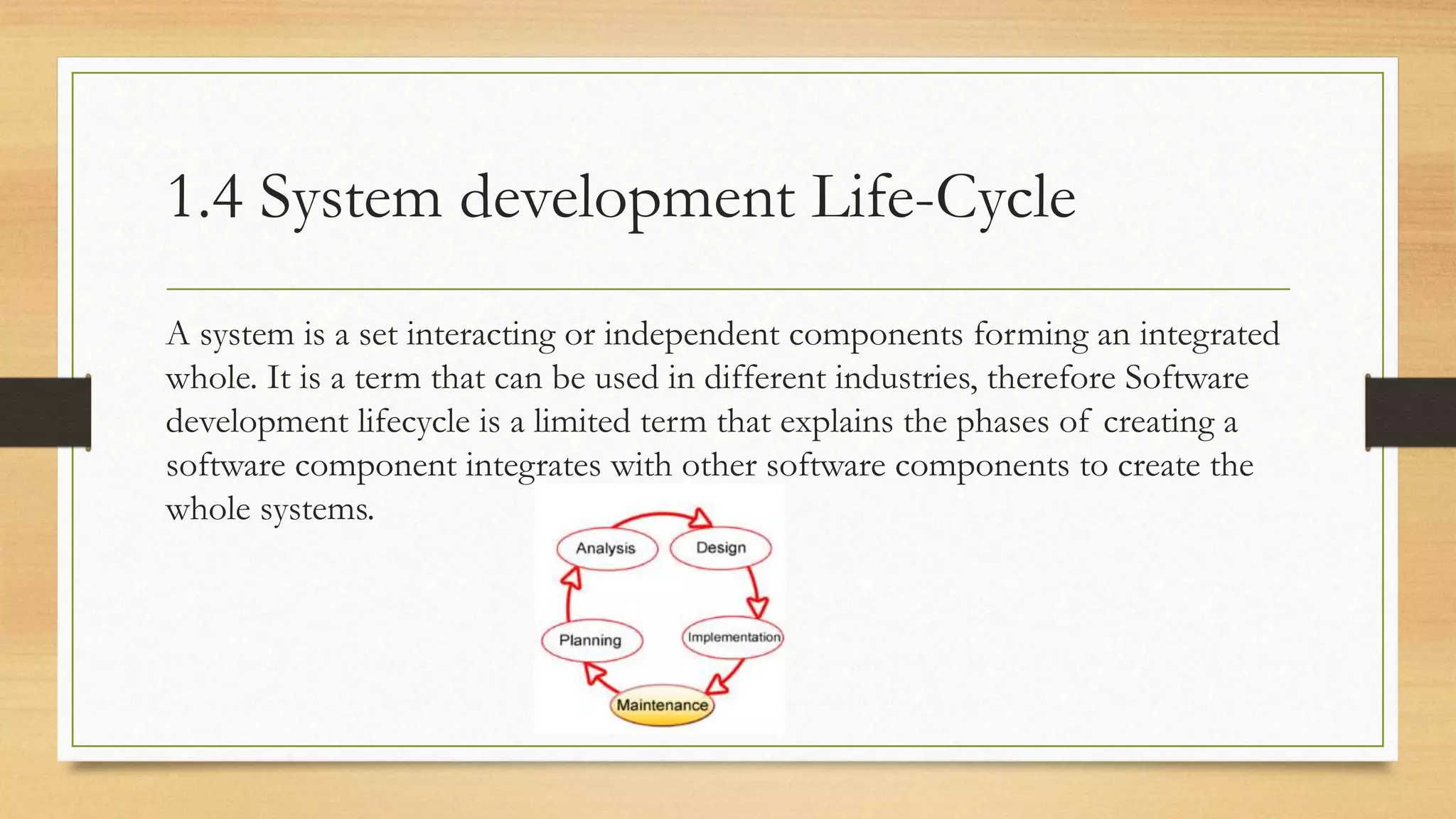

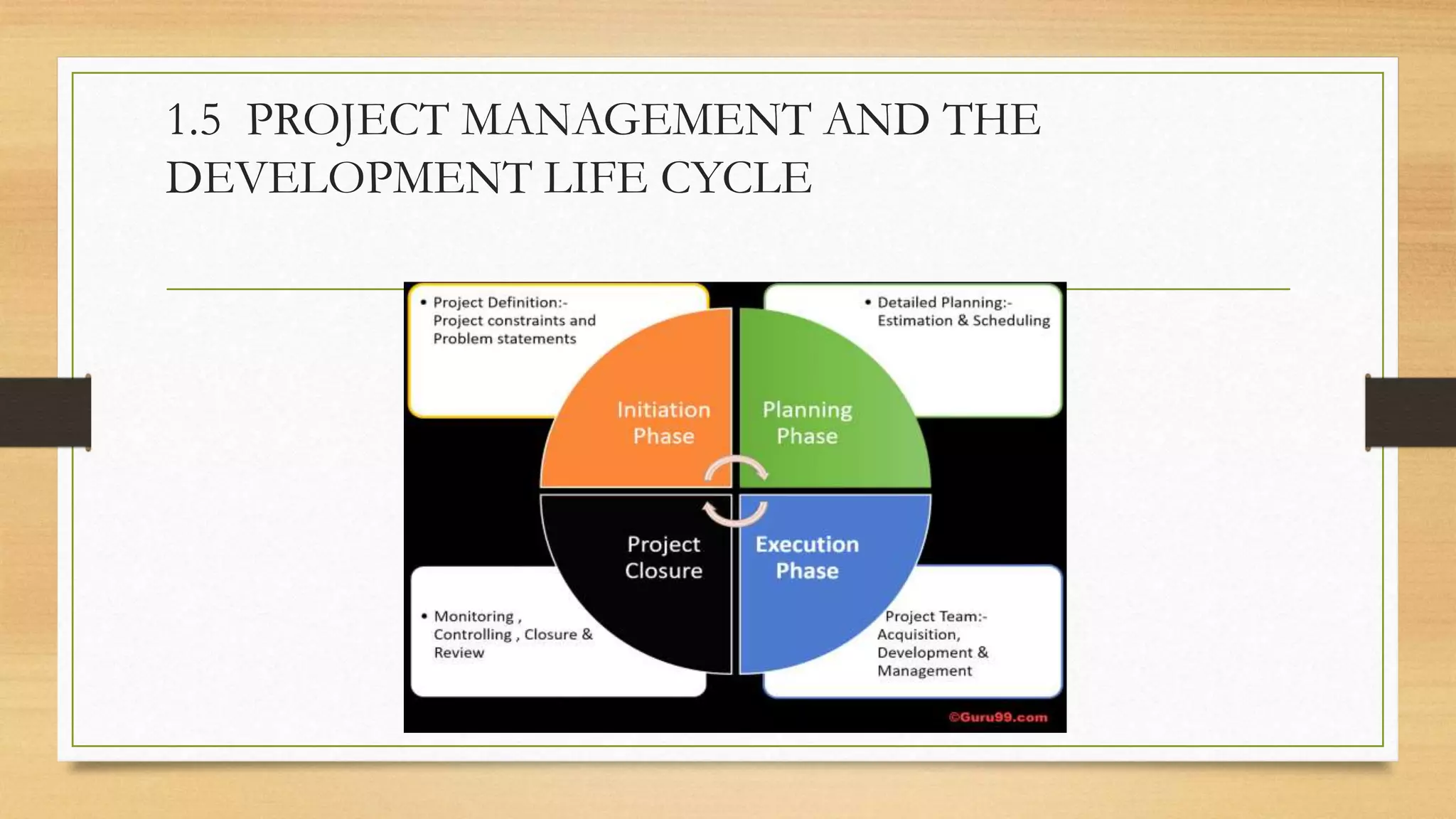

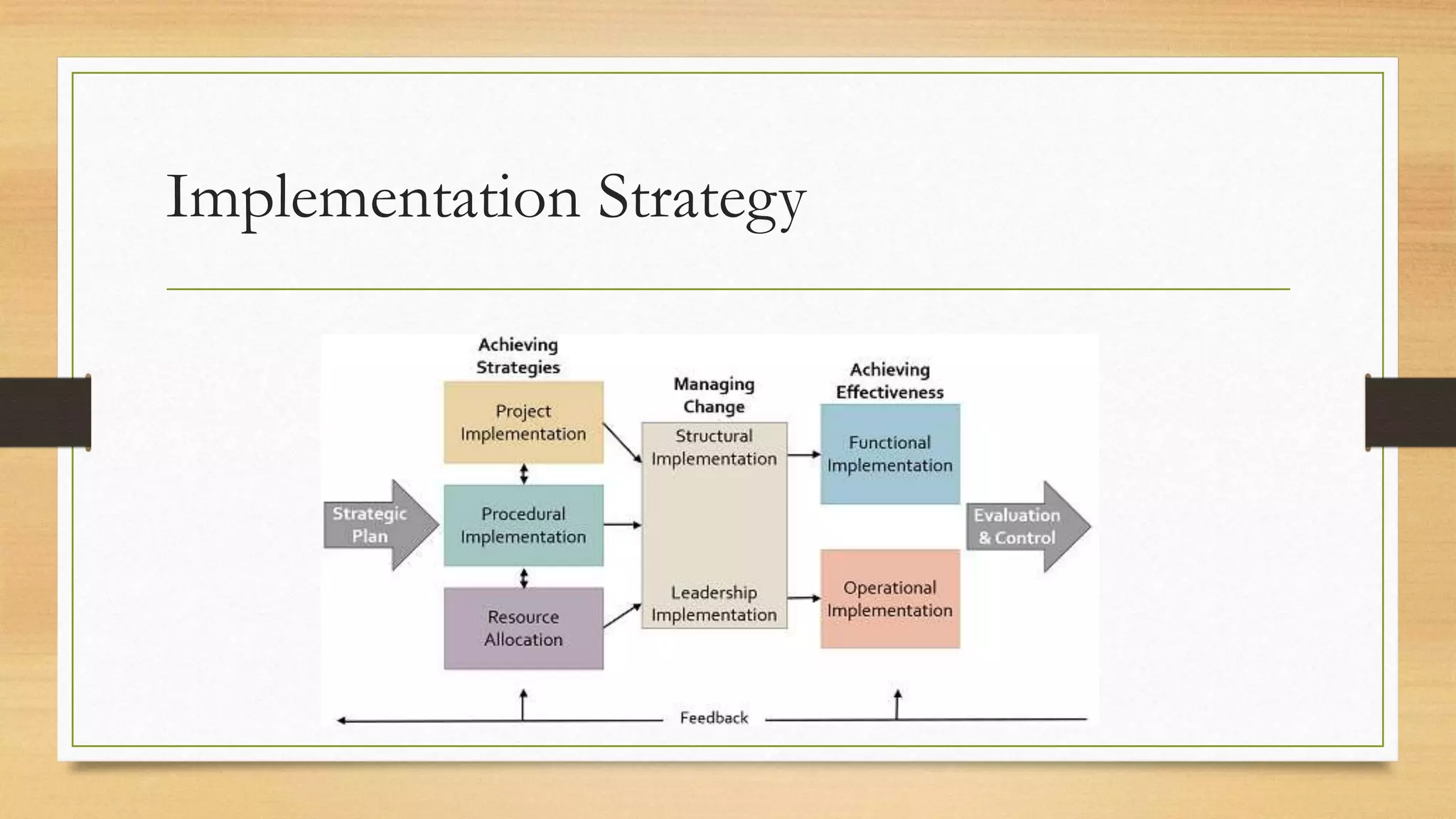

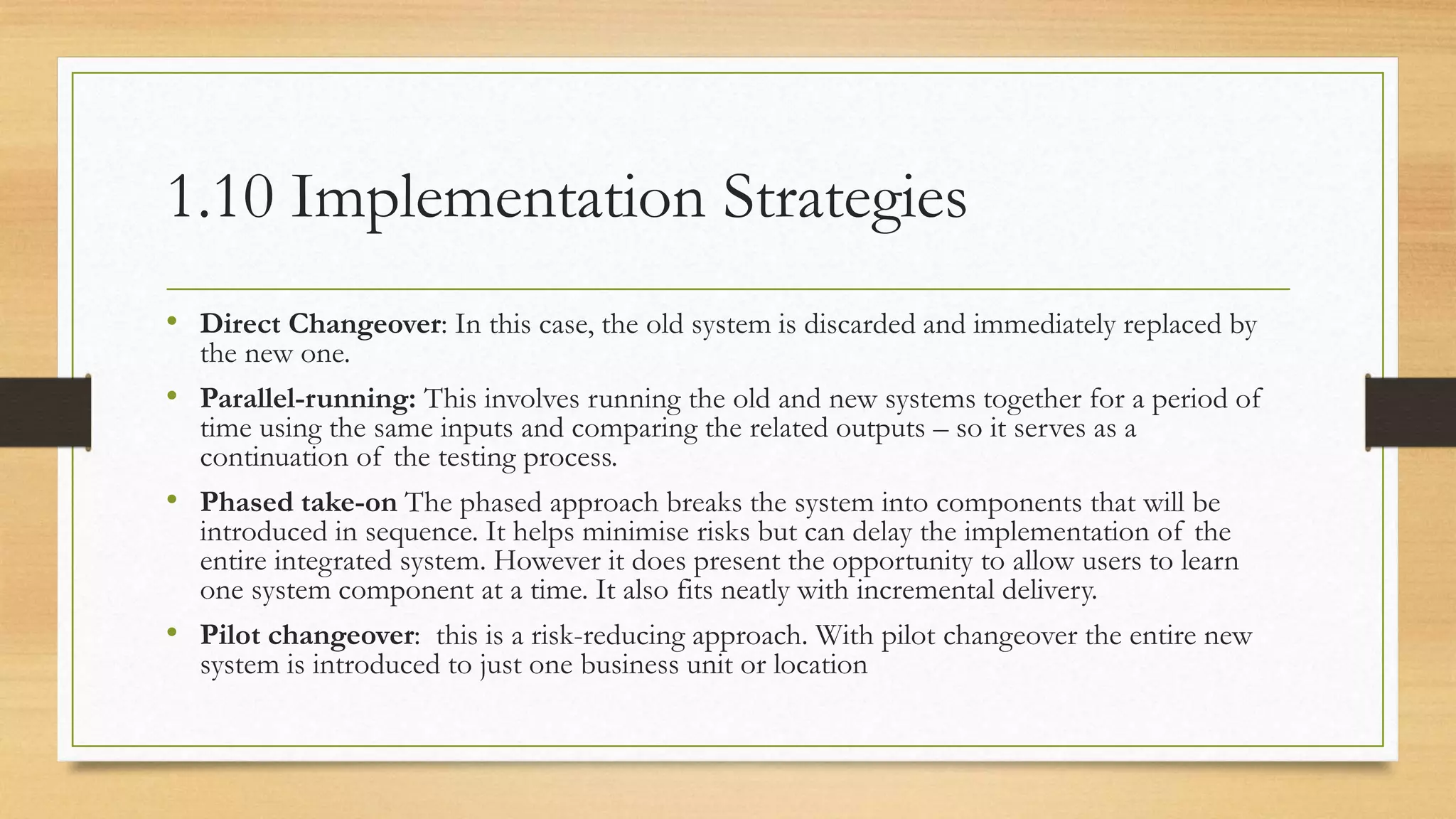

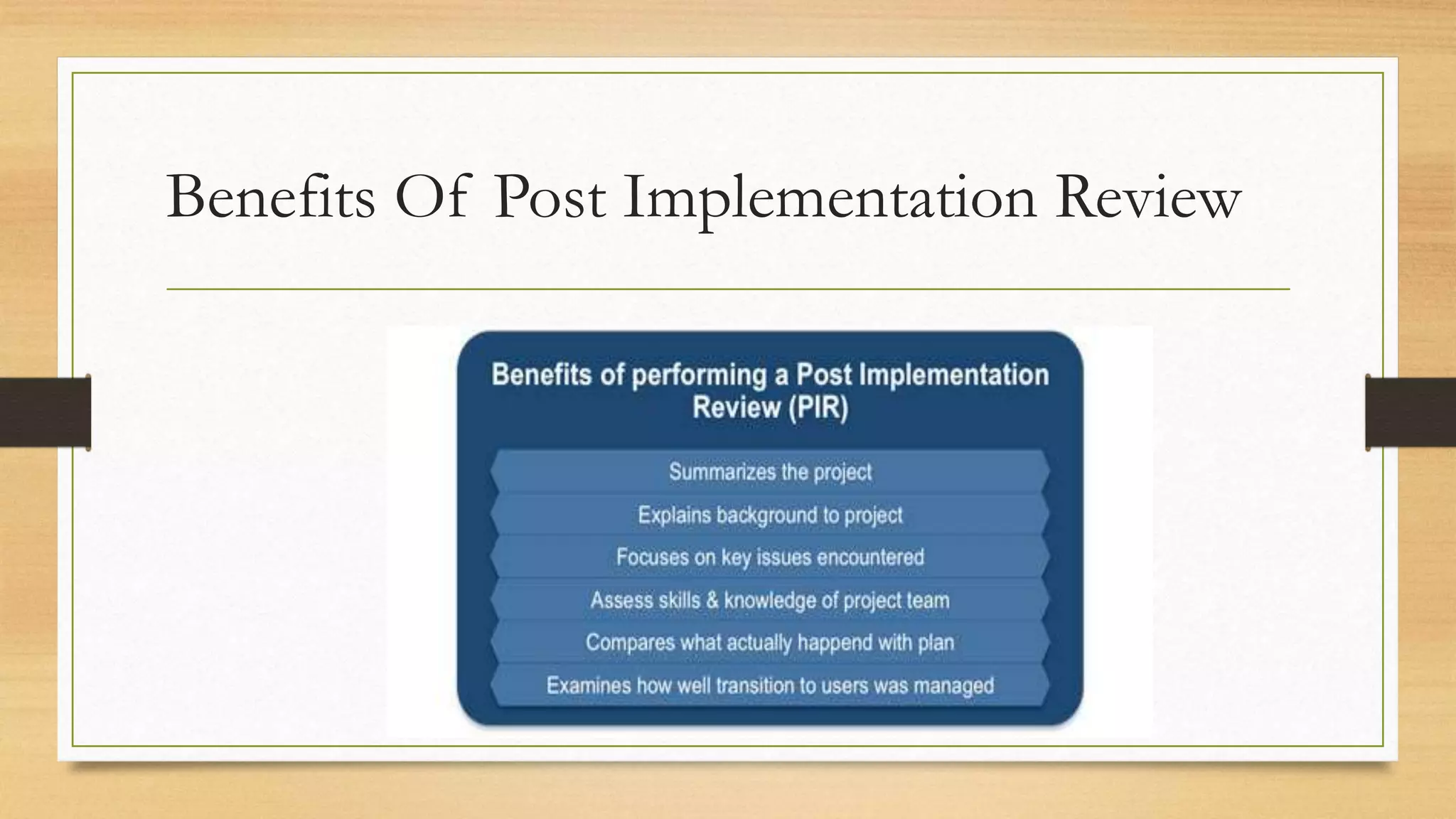

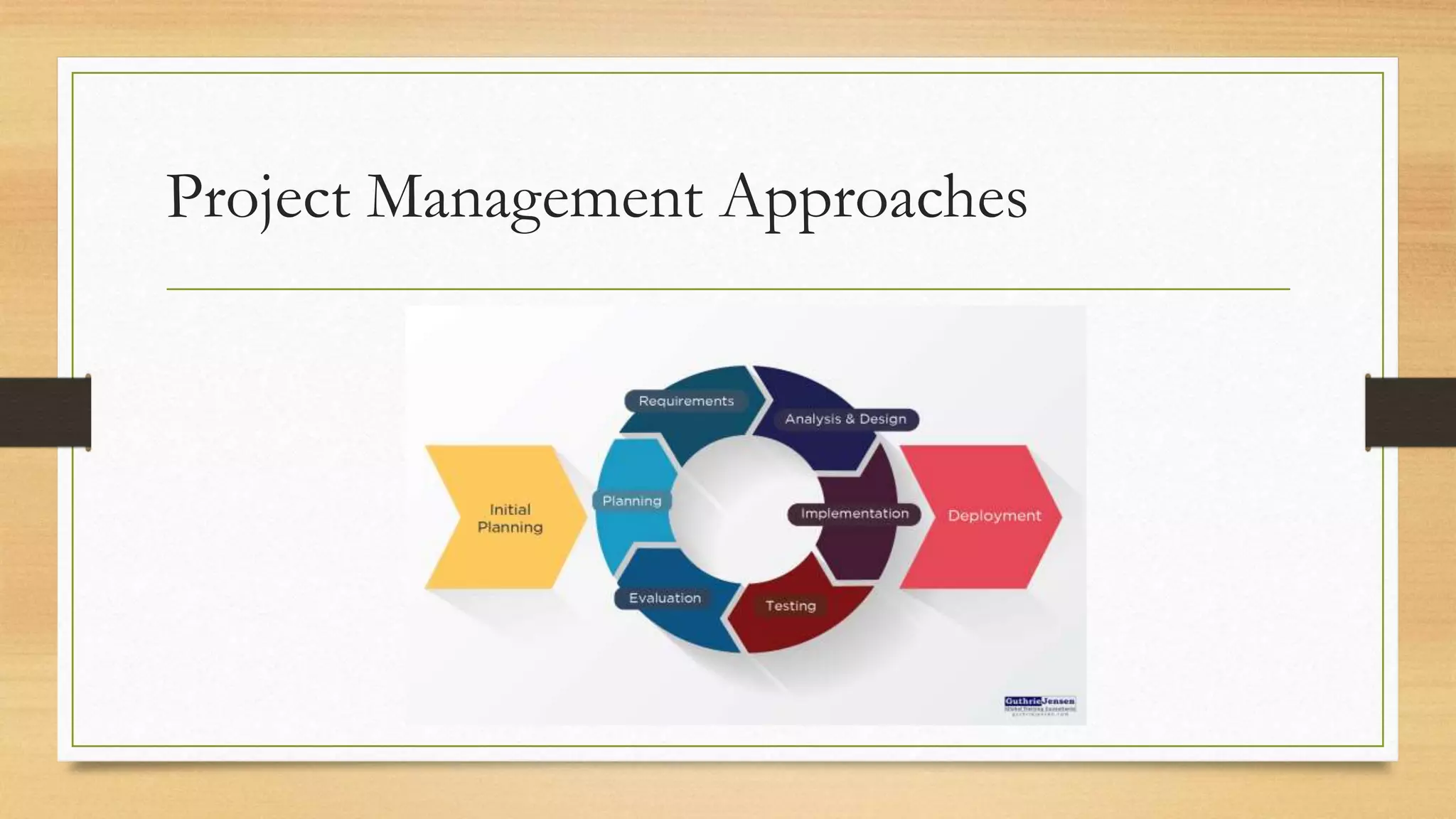

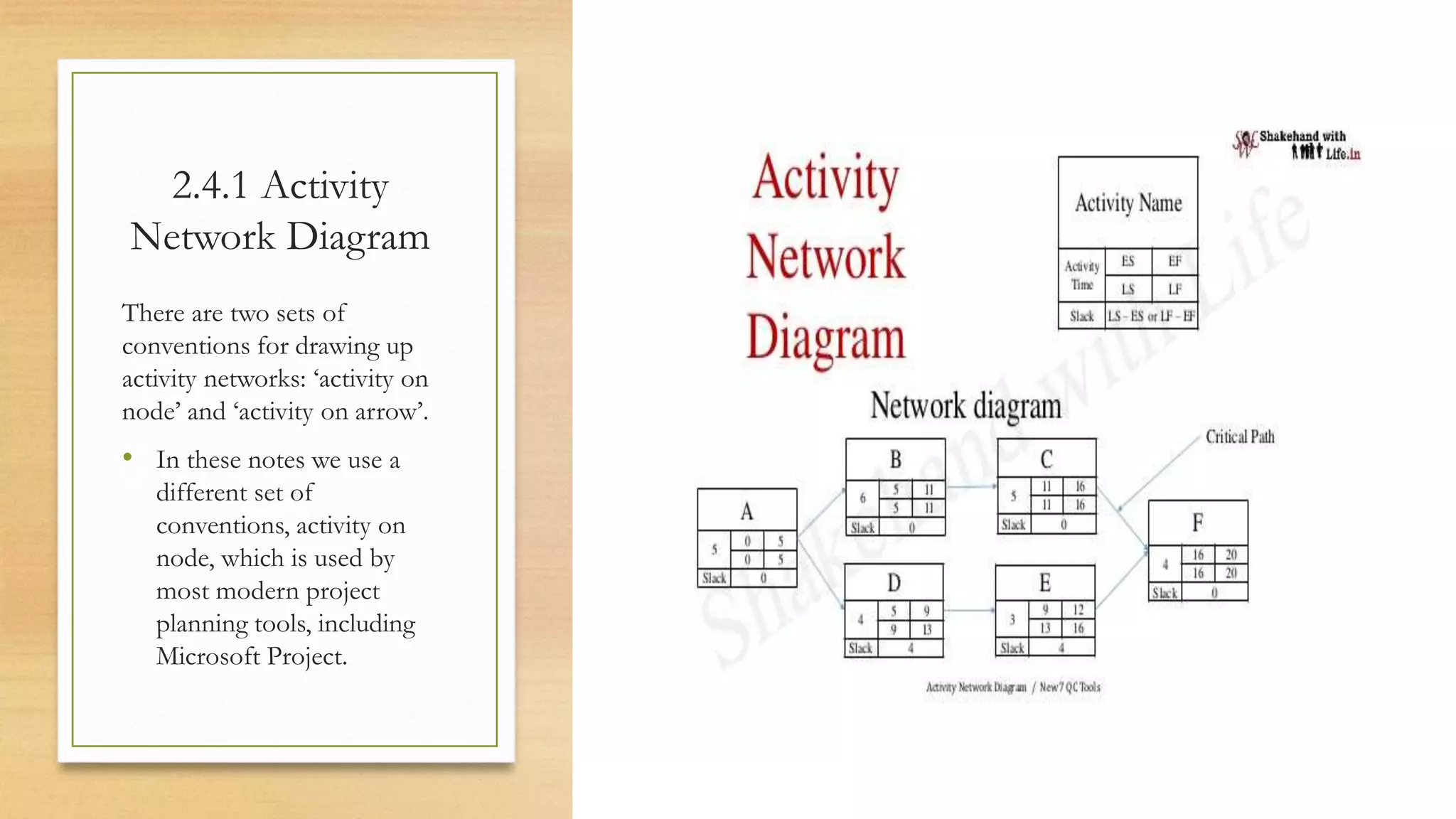

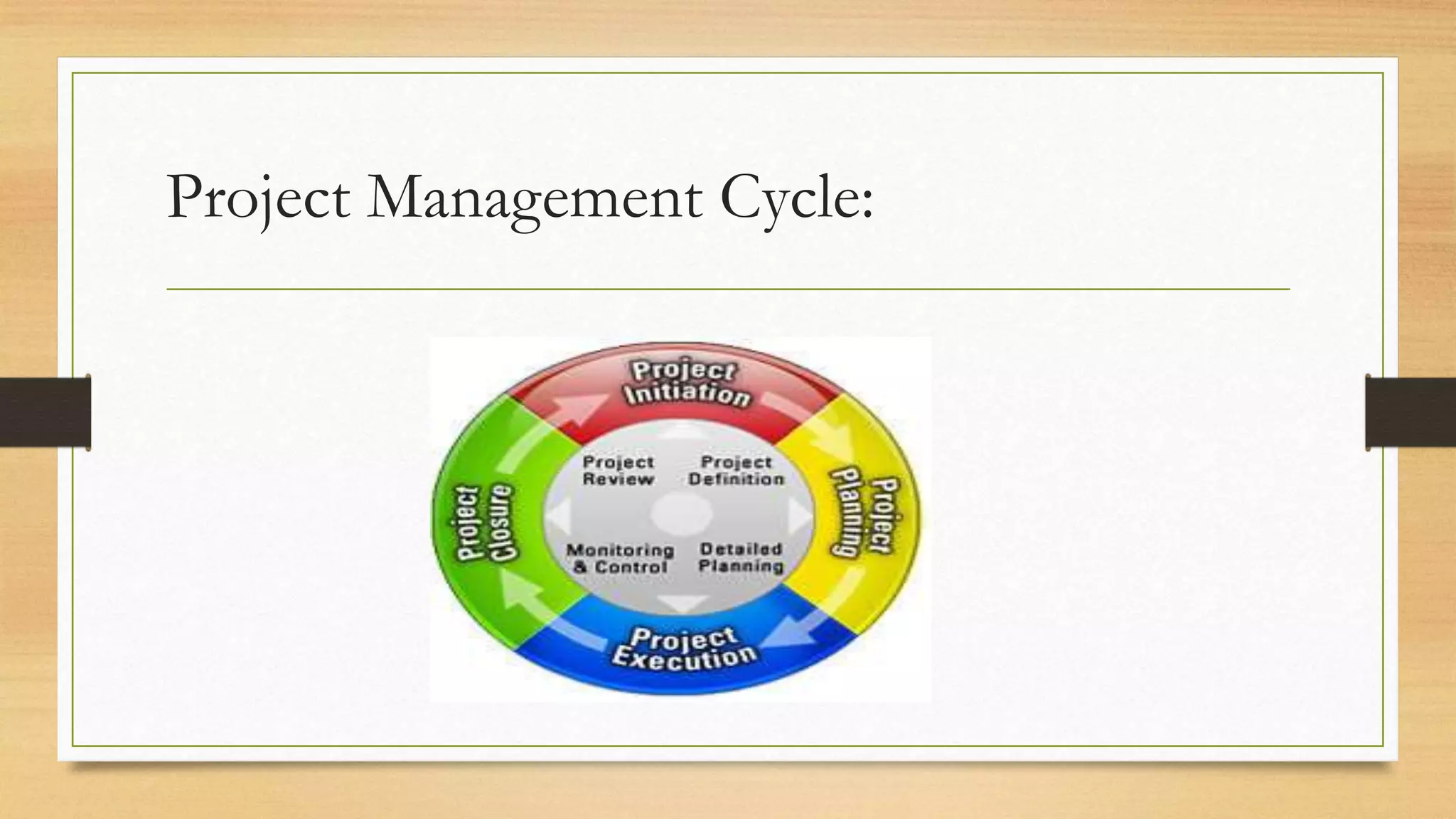

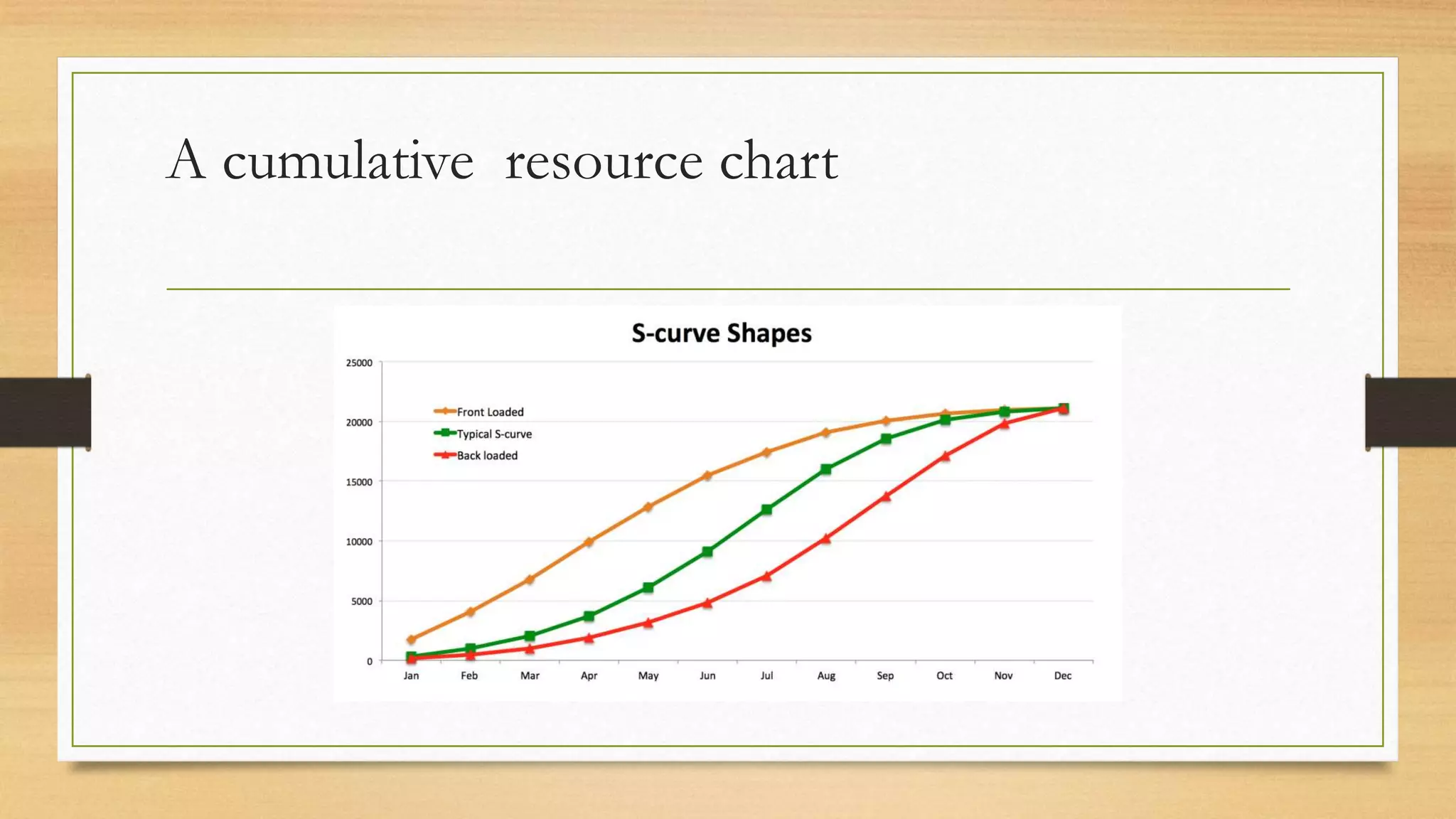

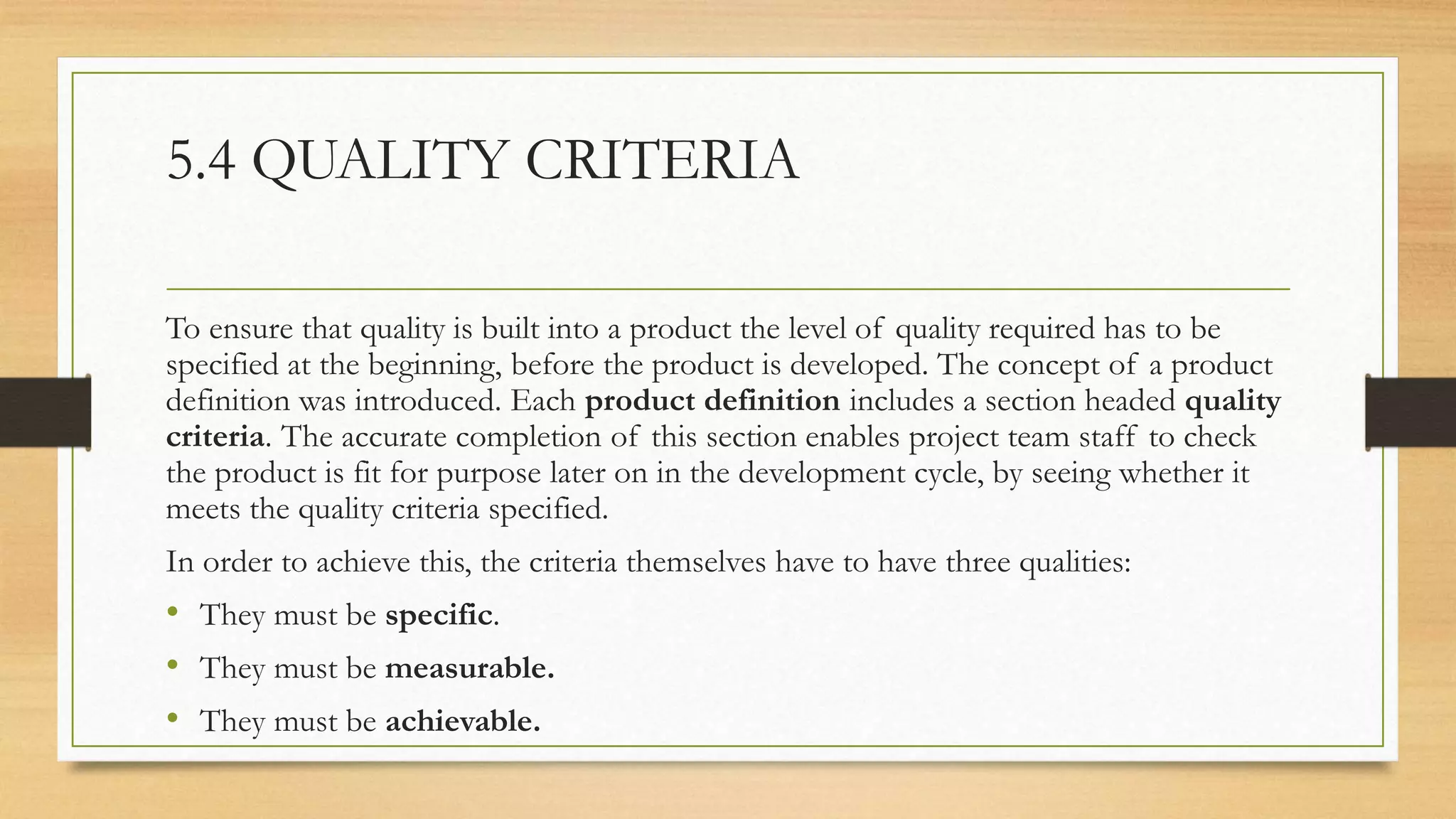

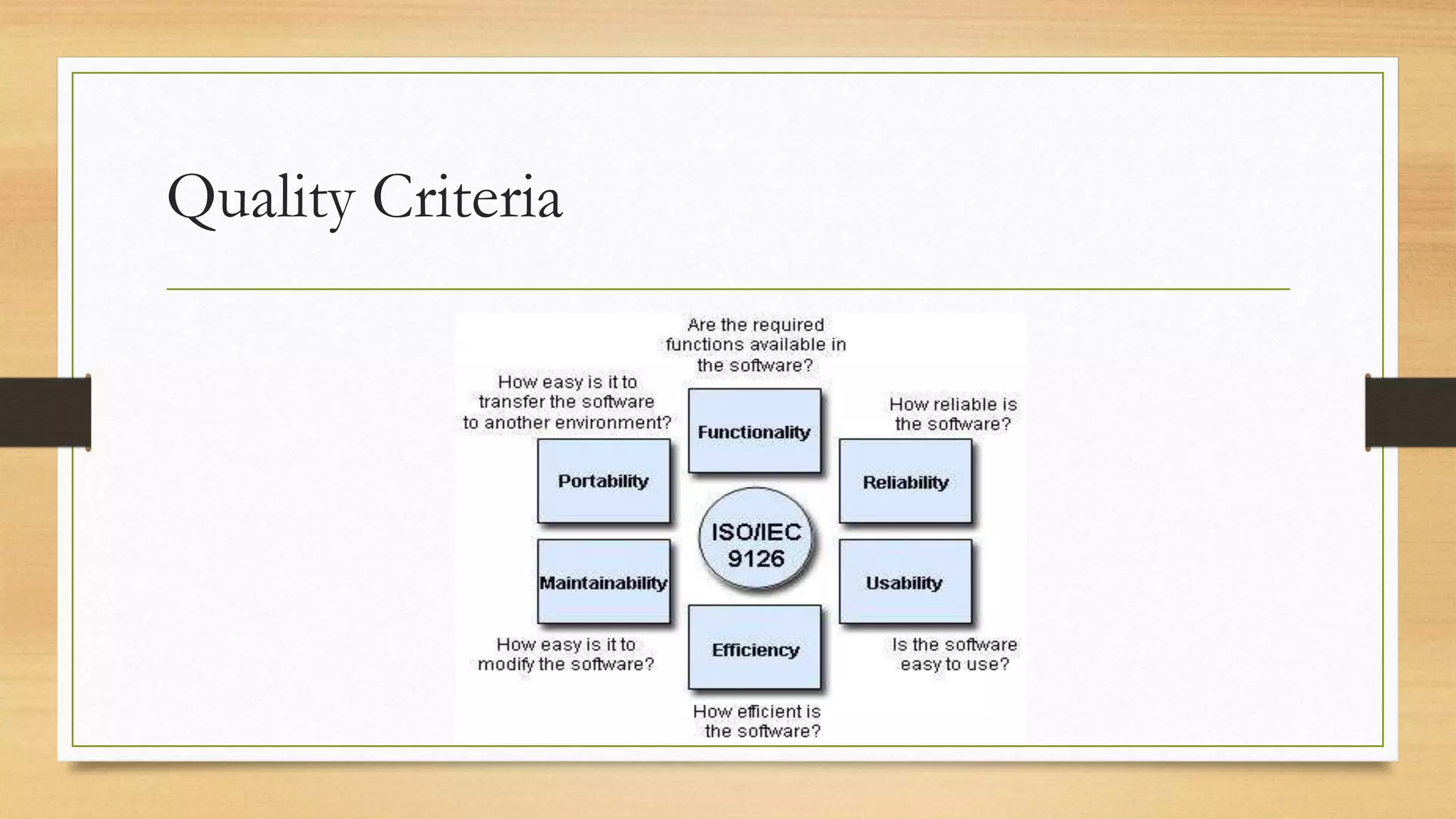

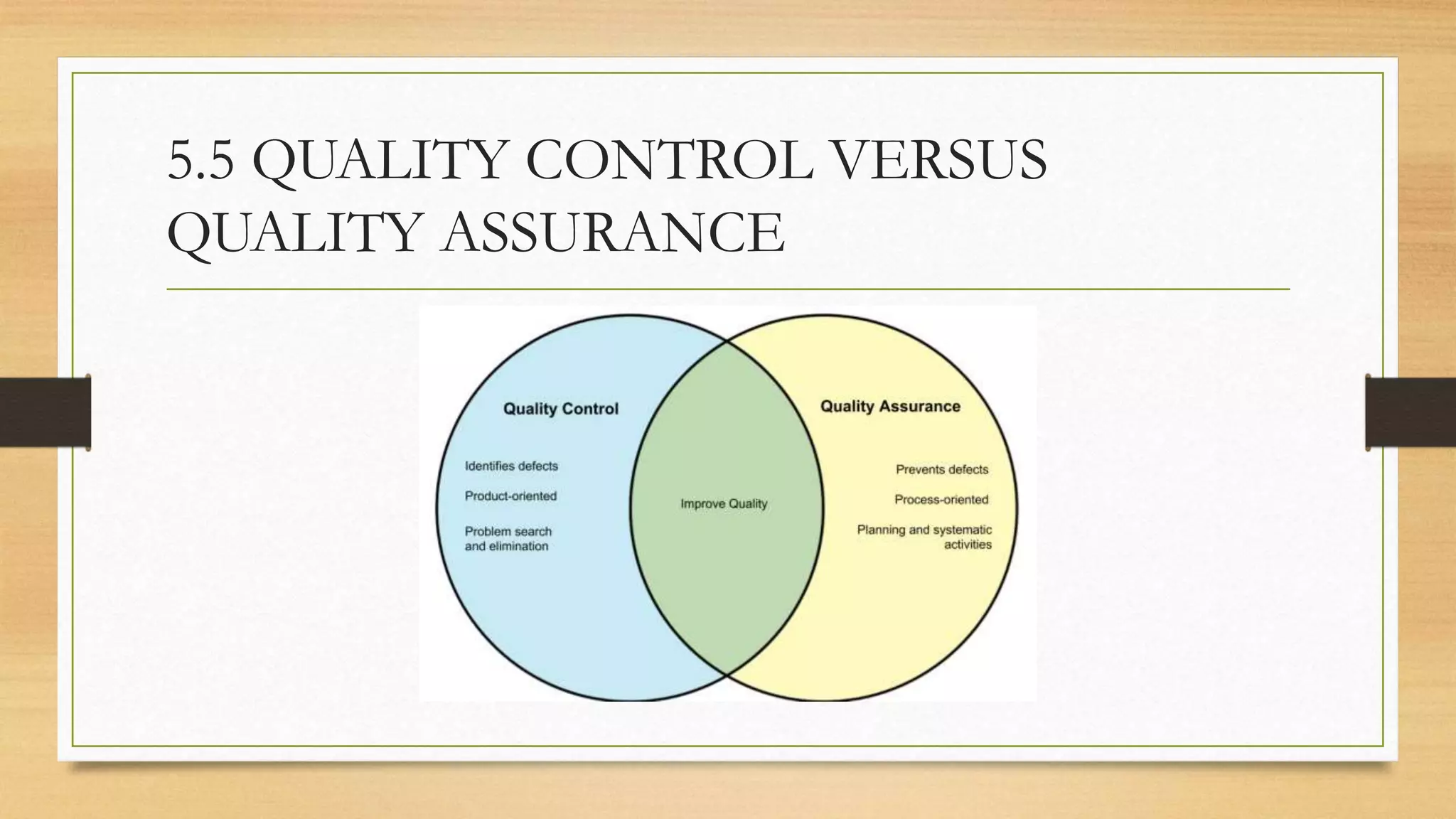

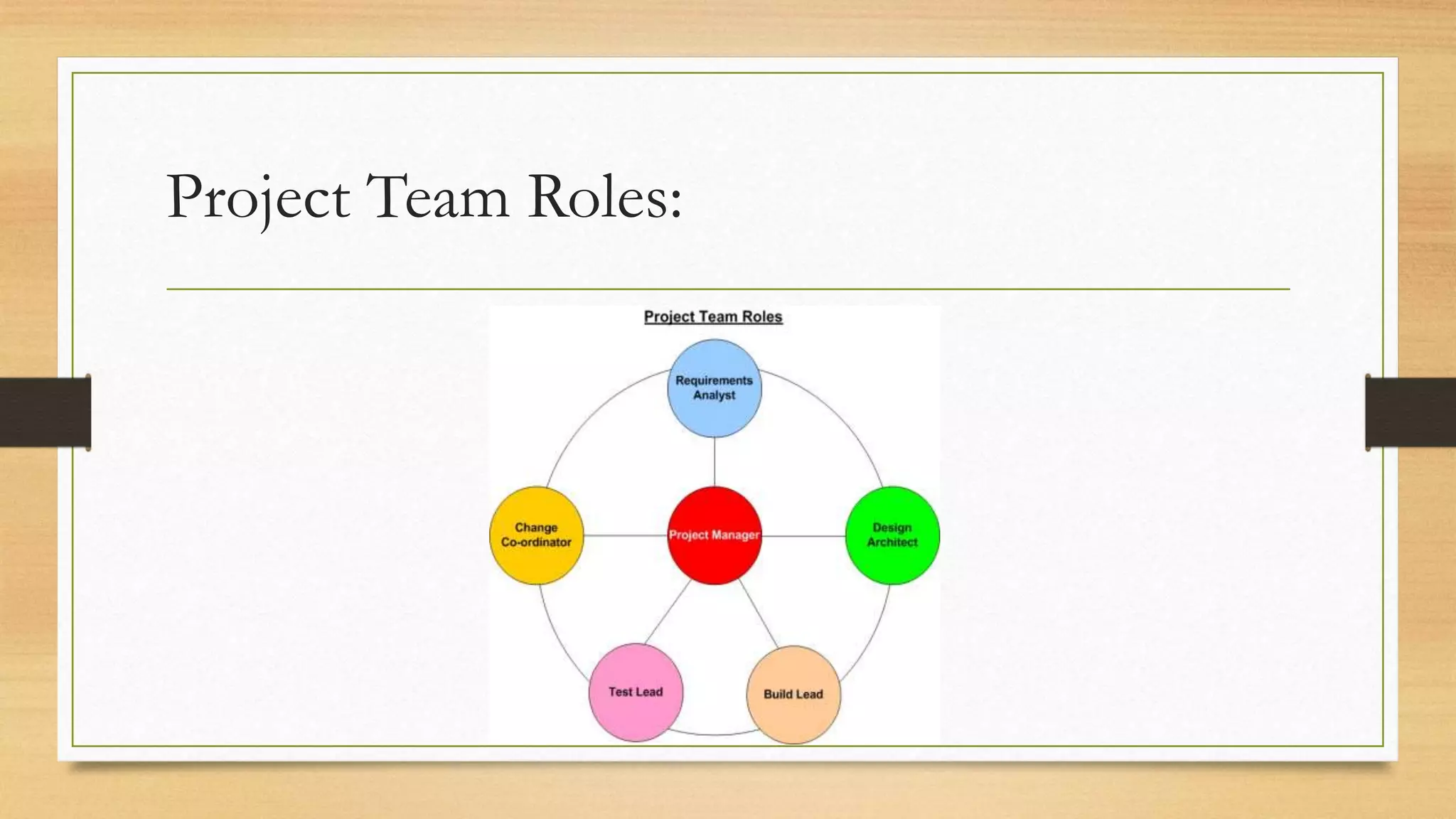

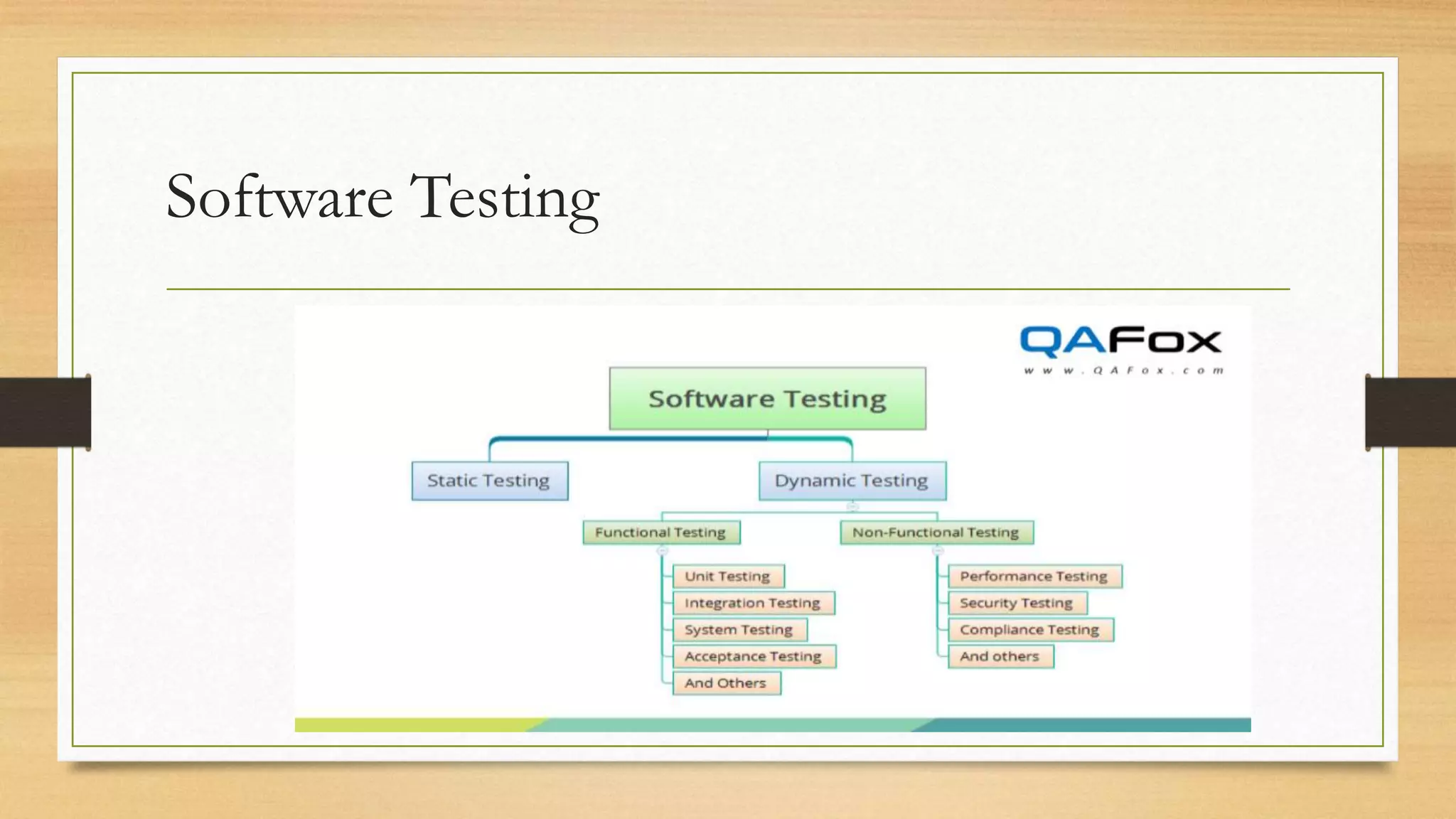

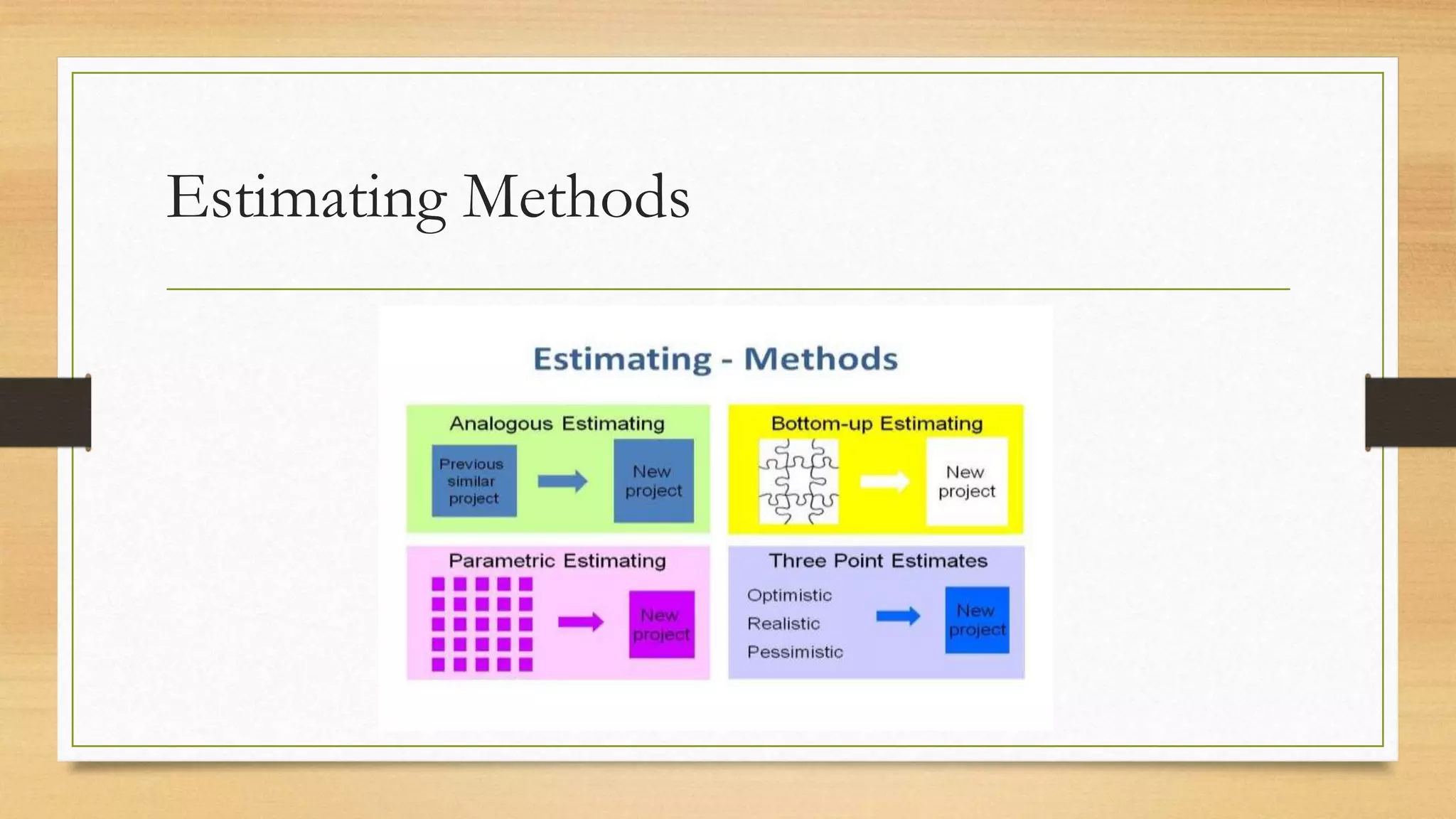

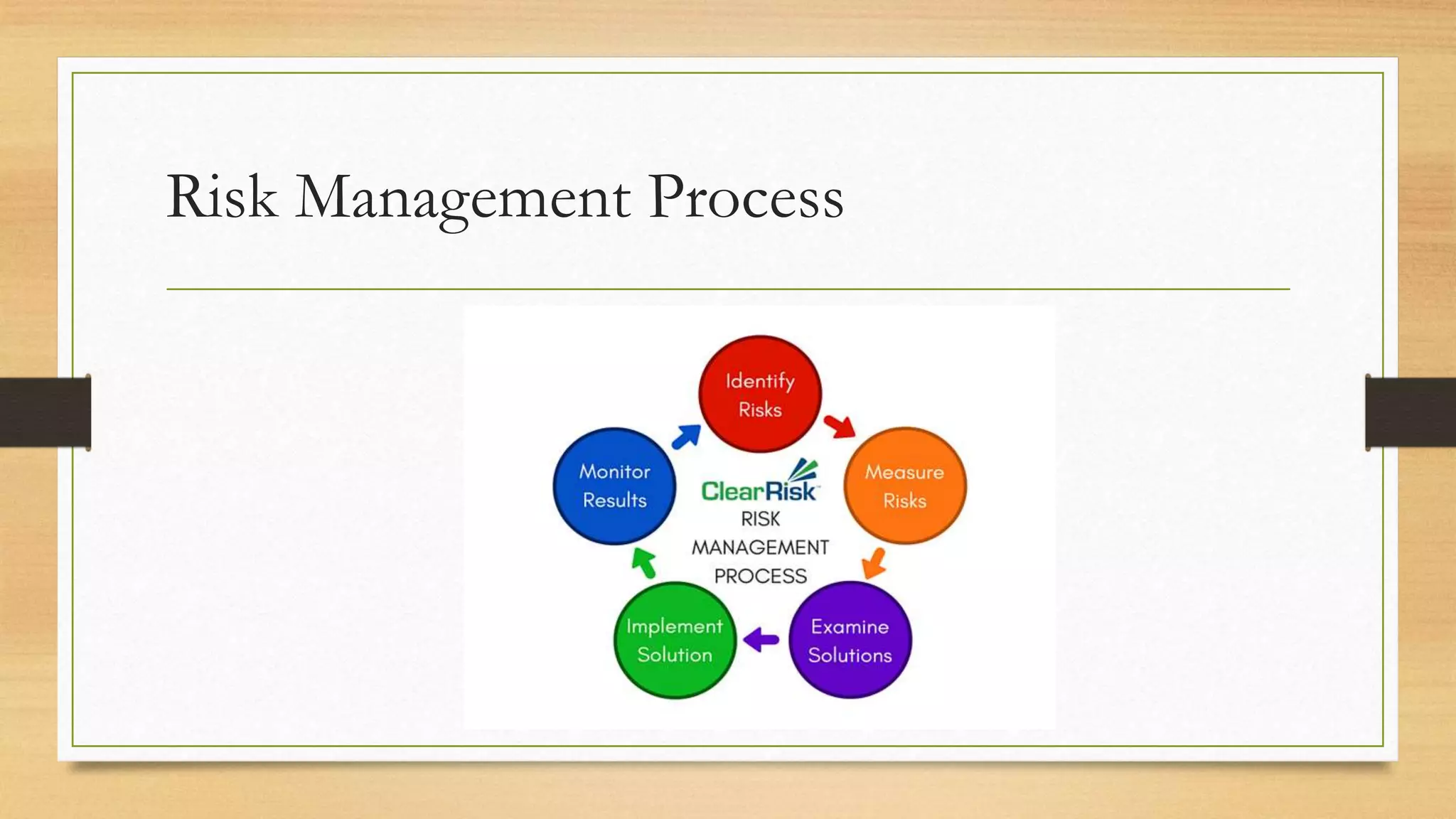

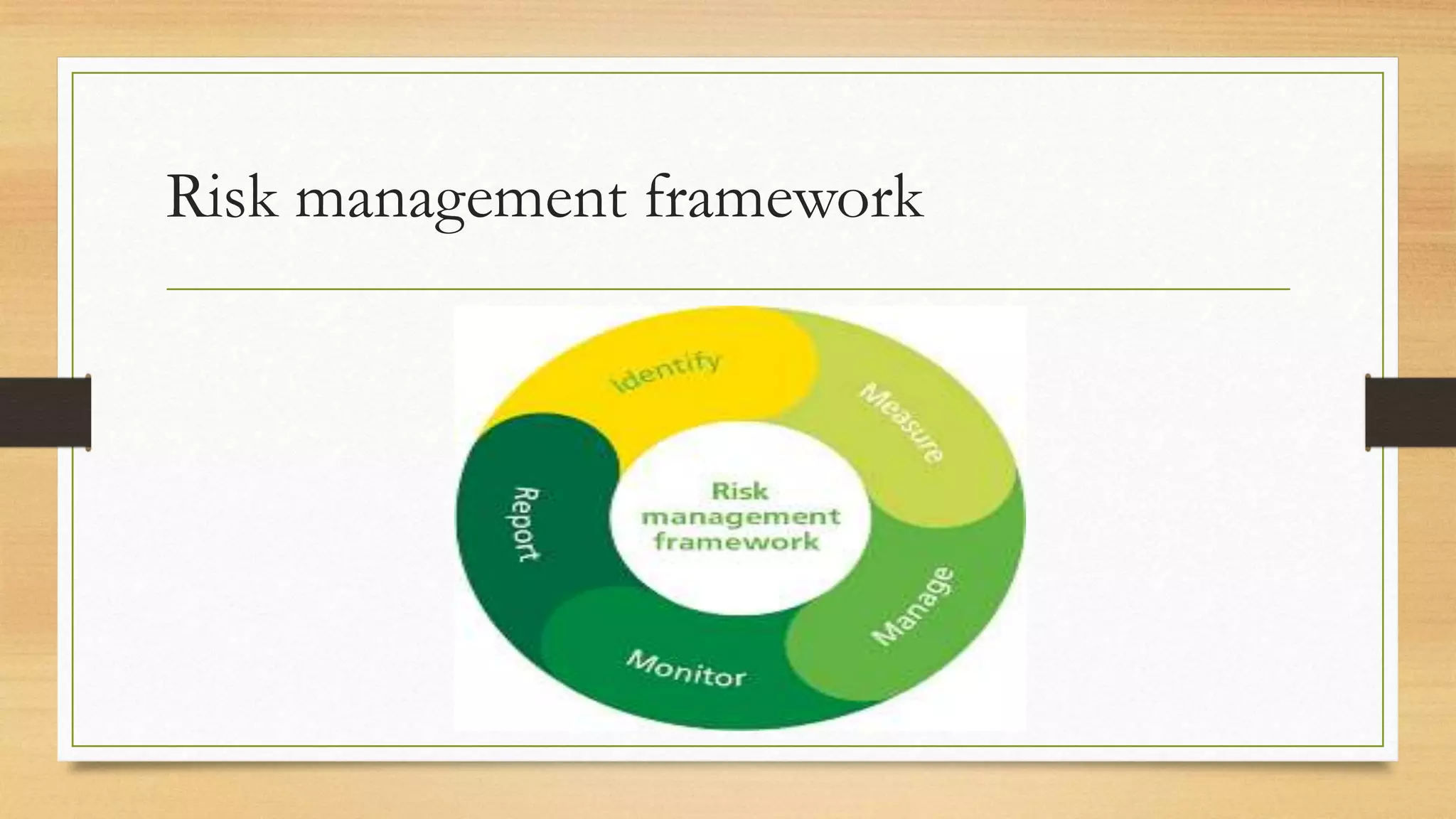

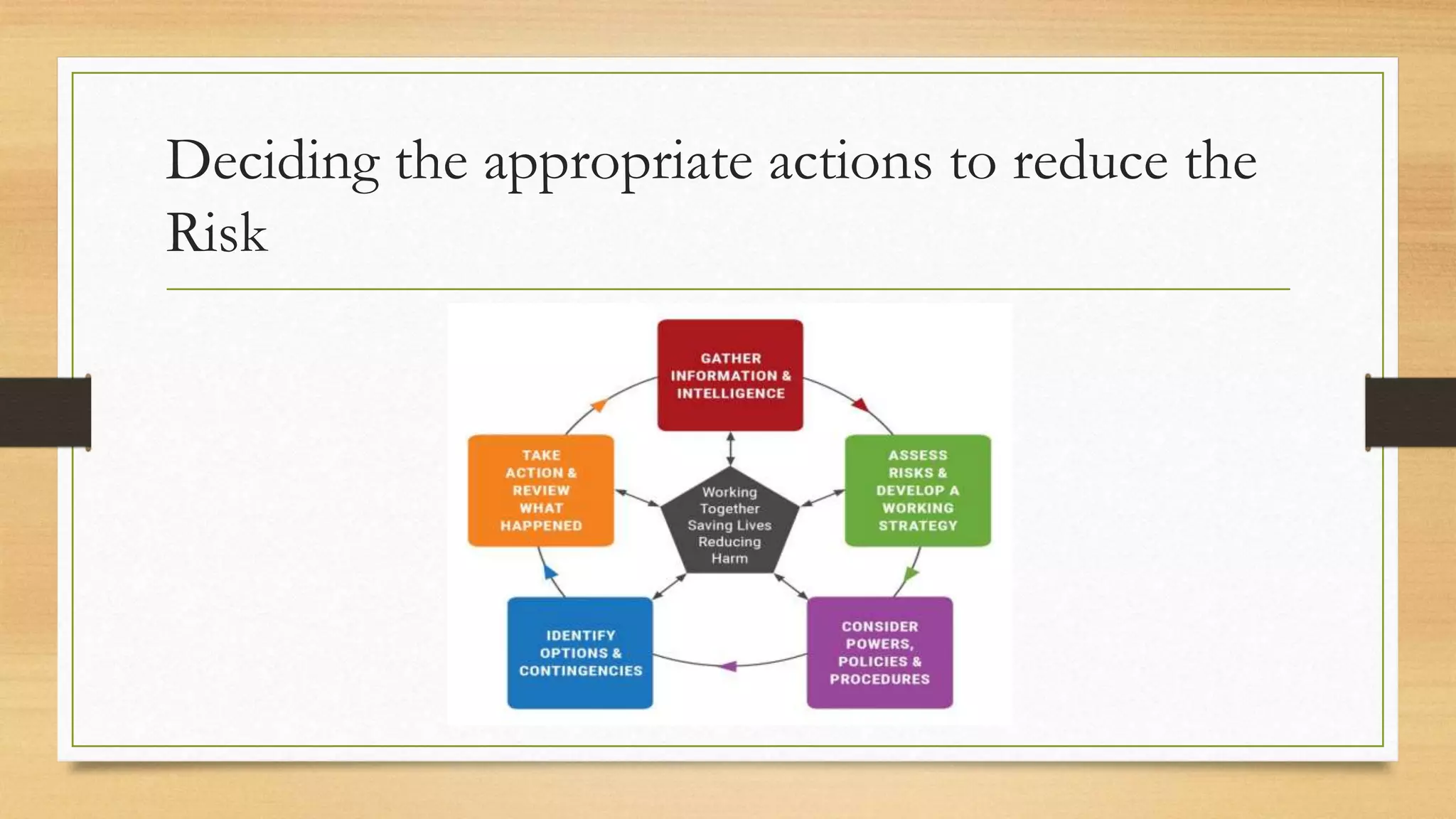

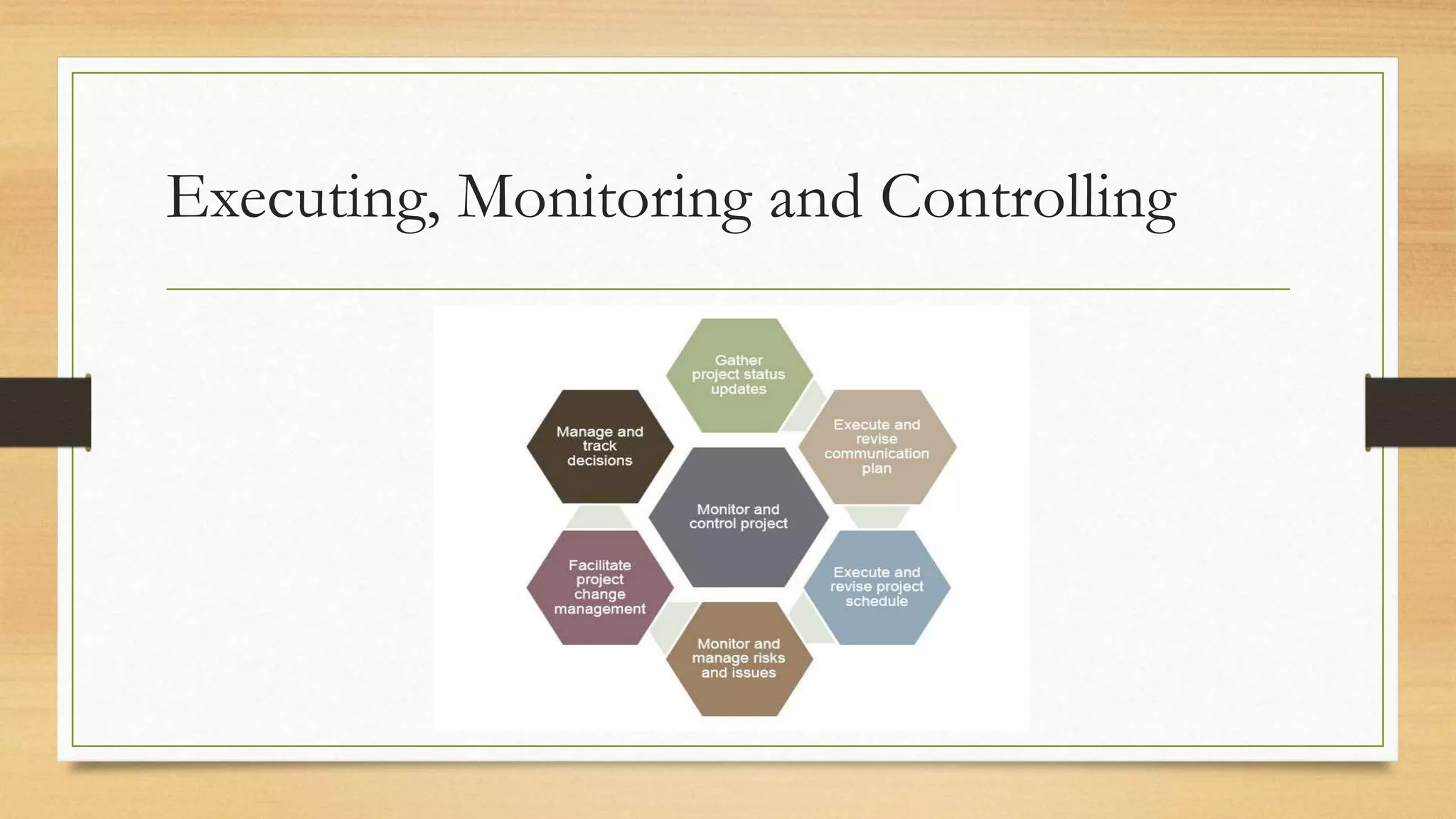

This document provides an overview of project management for IT-related projects. It discusses key topics such as project planning, monitoring and control, change management, quality, estimating, risk management, and project organization. It also describes the typical system development life cycle used for IT projects, including initiation, planning, analysis, design, implementation, maintenance, and review. Project success relies on elements like clear responsibilities, objectives, control processes, change procedures, reporting, and communication. The document emphasizes the importance of planning, monitoring, control, and addressing issues, changes, risks, and stakeholder needs throughout the project life cycle.