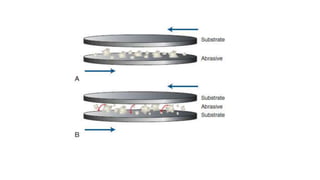

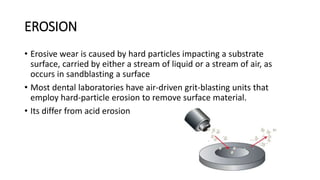

This document discusses materials and processes used for cutting, grinding, finishing and polishing in dentistry. It covers the history of abrasives, applications in dentistry, instrument design principles, benefits of finishing/polishing, biological hazards, and common abrasives like aluminum oxide and diamond. The finishing process involves bulk reduction, contouring, finishing and polishing steps using increasingly finer abrasives to produce a smooth surface. Factors like hardness, grit size, bonded/coated/nonbonded abrasives, and motion type are discussed.