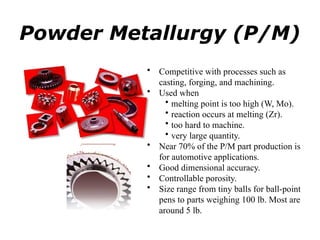

Powder metallurgy (PM) is an ancient and evolving technique for producing metal parts from metallic powders through processes like blending, compaction, and sintering. It offers advantages such as controlled porosity, economical mass production, and the ability to use a wide range of materials, but it also has limitations, including high material and tooling costs. PM is particularly prevalent in automotive applications, with a significant focus on producing reliable, precision components.

![History of Powder

Metallurgy

• IRON Metallurgy >

• How did Man make iron in 3000 BC?

• Did he have furnaces to melt iron air blasts, and

• The reduced material, which would then be

spongy, [ DRI ], used to be hammered to a solid or

to a near solid mass.

• Example: The IRON PILLER at Delhi

• Quite unlikely, then how ???](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/powdermetallurgy1-241109044208-78b9c02e/85/Powder-Metallurgy-1-mechanical-engineering-pptx-11-320.jpg)

![Powder Metallurgy Merits

o The main constituent need not be melted

o The product is porous - [ note : the porosity can be controlled]

o Constituents that do not mix can be used to make composites, each constituent

retaining its individual property

o Near Nett Shape is possible, thereby reducing the post-production costs,

therefore:

Precision parts can be produced

The production can be fully automated, therefore,

Mass production is possible

Production rate is high

Over-head costs are low

Break even point is not too large

Material loss is small

Control can be exercised at every stage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/powdermetallurgy1-241109044208-78b9c02e/85/Powder-Metallurgy-1-mechanical-engineering-pptx-17-320.jpg)

![Powder Metallurgy Disadvantages

o Porous !! Not always desired.

o Large components cannot be produced on

a large scale [Why?]

o Some shapes [such as?] are difficult to be

produced by the conventional p/m route.

• WHATEVER, THE MERITS ARE SO

MANY THAT P/M,

• AS A FORMING TECHNIQUE, IS GAINING

POPULARITY](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/powdermetallurgy1-241109044208-78b9c02e/85/Powder-Metallurgy-1-mechanical-engineering-pptx-18-320.jpg)

![Powder Metallurgy

• An important point that comes out :

• The entire material need not be melted to fuse it.

• The working temperature is well below the melting

point of the major constituent, making it a very

suitable method to work with refractory materials,

such as: W, Mo, Ta, Nb, oxides, carbides, etc.

• It began with Platinum technology about 4

centuries ago … in those days, Platinum, [mp =

1774°C], was "refractory", and could not be

melted.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/powdermetallurgy1-241109044208-78b9c02e/85/Powder-Metallurgy-1-mechanical-engineering-pptx-19-320.jpg)