, Phonological systems are rule-governed; that is, they operat.docx

- 1. , Phonological systems are rule-governed; that is, they operate according to certain rules and are : manifested as patterns.The word used for individual speech sounds is phones, and the study of the ; characteristics, or features, of phones of all languages is called phonetics (Yule, 2010). Although the I focus is on the English sound system, it is important to note that each language is systematic in its patterning, and that although similarities exist across all languages, differences abound. Phonology The study of the sound system of languages, called phonology, helps teachers understand many challenges English learners (ELs) face, both in hearing and producing the sounds of a new language. This knowledge also assists teachers in diagnosing errors second language (L2) readers typically make when reading aloud and in predicting how this affects comprehension, accuracy, and fluency. This section is fundamental to an understanding of linguistics because it introduces a number of important concepts that are revisited at other levels of language. The first section is on the basic con- cepts of phonology; the second is about the consonants of English; the third provides an overview of the English vowels; and the fourth is about suprasegmentals, the phonological phenomena affecting pronunciation at word and phrasal levels. An examination of the learning processes involved when

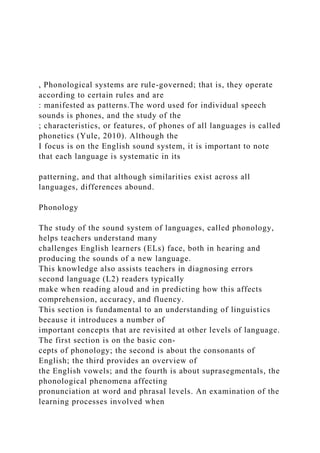

- 2. a learner encounters a new language is presented along with activities to support educators and students in discovering the characteristics of how the sound systems function, as well as ways to apply knowledge of phonology to help students overcome difficulties. See Figure 5.1. g "i,': .§ ~ _;; Sounds l--- --L-..-. ~ ~'------........-' = j _;; ..... = = "' @ Intonation Word stress Rhythm Features of connected speech Figure S.1. Phonology.

- 3. -[ill- A uniYersal concept across languages is the phone, or sound, as represe:-.?.:: ::-- .:. ..=~ o:::- 0::.~er 5;-::-.::... "- between brackets, such as [p ]. Note that [pl between brackets represents ti-.E s.:::. ~ 2..:'".i ~~ 'p ' in si.-.~ quotation marks represents the letter. The concept of phone is a uni·ersal o:-.e: a _e::cr or other syrr.x_ in brackets indicates thatit is part ofa system that includes all the world's languages. The Intemationa.. Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) includes all these phones using a unique symbol for each sound. The sound of [p] in English actually has three different variants, the aspirated [p] in 'pit', fr.:c unaspirated [p] in 'shopping' and the unreleased [p] in 'stop'. Even though English has these ya::- ants, called allophones, of [p ], they are still the same phoneme. That is, the same symbol is used.::- represent all the variants of [p] for English. A phoneme is represented by a symbol that includes L possible variants (allophones) of a particular sound in a particular language, and is written ben..,·ee:- slashes, as in / p /. Aspiration of a sound involves the accompaniment of a puffofair on the sounc. :: onset. You can detect this by putting your finger in front of your lips when starting to say 'pif. =: you say the word 'pit' twice, once with aspirated /p/ and once with unaspirated /p/, the meani:; of the word does not change. However, in Hindi and Arabic there are two [p] phonemes becauE-c

- 4. speakers produce both aspirated and unaspirated sounds in the same environment, and they can:- · be used interchangeably. They are different at the phonemic level. Other languages, such as Korea:- do not make a distinction between [p] and [f], so there would be only one phoneme represent::-; those Korean allophones. A specific instance of phonemic difference is in Spanish, which has r - /r/ phonemes, one written as 'r', and the other as 'rr', as in 'pero', 'but', and 'perro', 'dog' . As y~ - can see, a phonemic difference indicates a meaning difference at the word level. The concepts of -etic and -emic are important for teachers to understand because they are used.= the fields ofboth anthropology and linguistics; both fields contribute crucially to the teaching of :.a.:-- guages. The term -etic refers to universal characteristics of languages or cultures, while -emic r~e:- to language- or culture-specific characteristics. The whole idea of universal properties of languat~ and cultures is a powerful one; within the bounds of our own cultural and linguistic cocoons, · = often assume that our way of experiencing the world is universal, and are often surprised wz we learn that it is not. When non-native English speakers cannot hear or produce the 'th' sounc: = 'three', and produce 'tree' or 'free', we may wonder why they do not say 'three', which is so sim;· - The fact is that 'th' is quite rare across the world's languages, so it is no wonder that ELs have c._:- ficulty with this pronunciation. At the word/concept level where culture and language meet, it is surprising to learn that :-.a- ther Vietnamese nor Swahili has the generic word 'aunt'. In

- 5. addition, mother's sister, father 's sis:2: uncle's wife, and so on must all be referred to by different words; the relationships and roles des.:.;- nated by these different words are culturally determined. This will be addressed in the section::.- semantics. In becoming more aware of the needs of ELs in the classroom, educators should prep~- themselves to be surprised rather than judgmental, for what they say and do can be a cons-z..- source of wonder and learning for the whole class. Systematicity of English Consonants In this overview of sounds and the rules that underlie them, consonants are examined. Eng·:.- consonants are formed by affecting the passage of air through the vocal tract in various ways. -:-- chart in Figure 5.2 provides information on the following: the place of articulation for each soc from front to back in the mouth, the pairing of sounds via their voicing properties, and whether ::...: passing through the vocal tract stops or continues. In studying the chart, note that most consonant phonemes are represented by letters of = alphabet, while other symbols represent sounds that are written with two letters. For the systerr. · be useful and clear, a symbol must uniquely represent only one phoneme. A key word below e=--· non-alphabetic symbol on the chart helps to identify the sound it represents. 67 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language

- 6. English Consonanis Manner Bilabial Labio- hlter- Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal Place <lental dental+ Stop /pl - top /ti -two /kl - carVoiceless /bl - bee !di-do /g/- goVoiced Nasal /ml-me /n/-no /rj/- ring Voiced only Flicative /fl -fun /e /- /s/ - so I f / - shoe /h/have Voiceless lltick /vi- vote lzl - zooVoiced /of - /3/visionthe Affticate ltfl- watc/1Voiceless Voiced Id!, /- joy Glide lwl why /j/-yes /wi/ Voiced only Liquid /I/ love Voiced only /r/ rot Figure S.2. The consonant system of the English Language Pause and Reflect 1. With a partner, produce each sound to become more familiar with the overall system.

- 7. 2. English sounds are produced using three articulators: the lips, teeth, and tongue. Consult the chart to identify which articulators are used to produce each phoneme. 3. The place of articulation from front to back in the vocal tract is where an articulator touches a location in the mouth. As you pronounce each sound again, try to describe its point of articulation. 4. Compare the labels of the place of articulation on the chart in Figure 5.2 with the positions in the vocal tract shown in Figure 5.3 . It, d, s, z, I, n I [ j, z, tj, d, y, r ] Ik, g, IJ ] [ p, b, m, w] [ A] [ f, v ] Labiodental Alveolar ridge: alveolars Alveopalatal ~'i:f~::d--- [ h ] Glottis: glottals I ? l

- 8. Velum: velars Uvula: uvulars Pharnyx: pharnygeals Esophagus Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) -"- Figure 5.3. Organs of Speech Production. From Why TESOL? Theories & Issues in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages in K-12 Classrooms by Ariza et al. Copyright© 2010 by Kendall Hunt Publishing Company. Reprinted by permission. It is important to note that all English phonemes, except for / h /, are made in the area from the lips to the velum. But each language has a different system of phonemes, some more, some less :han those of English. For example, Arabic speakers produce uvular, pharyngeal, laryngeal, and glottal sounds. So, you can imagine how difficult it is for English learners of Arabic to master such sounds. 1. Look at the voiced and voiceless pairs on the chart in Figure 5.4. Produce each voiced sound in the pair first, placing your index finger across your 'voice box' and trying to feel the vocal cords vibrate. 2. Now produce the voiceless member of each pair and note that there is no

- 9. vibration. Word-Initial Word-Medial Word-Final -:oiced zap phasing buzz ~. ·oiceless ~ap fa.!:,;ing bu~ Figure S.4. Voiced/Voiceless Pairs. The chart, along with Figure 5.2, illustrates that voicing is an extremely important feature of English. Except for nasals, /r/, /1/, /w/, /y/, and /h/, all consonants in the language occur in voiced a.~d ,·oiceless pairs, which is not a universal feature of languages in general. The voicing feature of -=:.nglish is so prominent that voicing contrasts occur in word- initial, word-medial, and word-final ;ositions, as shown in Figure 5.4 for the phonemes /z/ and /s/. Note that English spelling often ciscures the realities of sound similarities. 69 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Althoughmany languages have voicing pairs word-initially, several such as Spanish andGerman devoice consonants word-finally. Thus, Spanish- and German- speaking ELs tend to pronounce 'pig' as 'pick', 'cab' as 'cap', and 'fuzz' as 'fuss'. The process of devoicing in L2 learning is one kind of transfer or interference from a first language (Ll).

- 10. ~ 1. Locate the pairs (lbIpI, I diti, and I glkl). Do they stop the airflow, or continue it? 2. Locate the other pairs, called fricatives, and answer the same question. ~ Another important aspect of the English consonant system is how airflow is impeded. Stops completely do so, while fricatives obstruct the air flow, but allow it to continue. As you studied the chart and pronounced the various sounds, you might have noticed that the three pairs of stops were interspersed with pairs of fricatives. The pair lbIpI is produced in the mouth very close to IvI fl and Idltl is close to ltJId3I and also to lzlsl. Speakers of some languages have difficulty hearing and producing the difference between the lbl in 'cab' and the IvI in 'calve'. Although Spanish has both lbI and IvI phonemes, they may both be pronounced the same, namely as bilabial fricatives, where the sound is produced with air passing between the lips instead of stopping. The words 'very' and 'berry' are often pronounced almost identically by Spanish speakers. (It should be noted that generalizations made aboutvarious languages are not always accurate for all dialects of a language.) Speakers of some languages spoken in Ethiopia, as well as Korean, have difficulty with the IpIfI distinction. A Ethiopian friend once reported that his student from a rural area told him, "Flease, Sir, I am foor. I have no any money." A further example is that French speakers, who lack the voiced 'th' sound in their language, are likely to say' /zisl for 'this'; speakers of some West African languages might say 'dat' for 'that'; and speakers of yet another language

- 11. might say 'tree' for 'three'. As noted above, the two sounds that represent English 'th' are uncommon among the world's languages and so ELs will produce sounds from their own collection of phonemes that are closest to the English sounds. Thus, a second kind of Ll transfer, or interference, may occur for speakers whose languages lack the phonemic contrasts across the stopIfricative divide that English has. Pause and Reflect 1. One pair of sounds, /d3/- /tJ/ (as in 'jerry' and 'cherry') are stop/continuants (called affri- cates); /d3/ starts with /d/ and ends with /3/; /tJ/ starts with /t/ and ends with /f/. Look at the nasals and explain why they are placed where they are. Can you speculate why there are no nasals in the fricative columns? 2. Where do you find the semi-vowels (also called glides) on the chart in Figure 5.2? 70 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) The two affricate sounds can be difficult for non-native English speakers. For example, many Spanish speakers have difficulty distinguishing between /tJ/ and /J/ ('cherry' and 'sherry') in all environments, and between /d3/ and /tJ/ word finally ('badge' and 'batch'). These sounds may also be late-learned by English Ll children during language development. In fact, some other Eng-

- 12. lish sounds are difficult for both children and L2 learners. Nasals are found only in the stop columns in English and they are produced in the same manner as their counterparts, but with the impeding of air through the nasal passage. When that passage is blocked, as with a cold or a pinched nose, the voiced stop is produced, "by dose is all plugged up." Some Spanish speakers may have difficulty producing /m/ word- finally, either omitting it ("My nay is_.") or substituting with /n/ or /11./ ("Hong Depot") . In consulting an IPA chart you will find that there are languages in the world with nasal fricatives. Can you produce any of them? Each semi-vowel and liquid is shown on the chart in Figure 5.2 in the column beneath its place of articulation. It might seem quite odd to see /1/ placed in the /dz/tf/ column until you experi- ment a bit and find that it is formed by touching the tongue tip at the alveolar ridge, although it could also be formed further forward or further back (Try it!). Speakers from Taiwan may produce /1/ for / oI as in 'raler' for 'rather'. Speakers of some dialects of English produce a palatalized /1/, touching the blade of the tongue at the palate rather than using the tongue tip. It might also seem strange to see /w/ in the bilabial column. But when /w/ is formed, as in 'wonder', the lips are round, thus, a bilabial sound. On the other hand, /y/, formed in the palatal area, has vowel-like properties as /w/ does. The two sounds are vowel-like because the airflow is not impeded in their production as with stops and fricatives.

- 13. Both L2 learners and English speaking children have difficulty with liquids and semi-vowels (glides). Thus, a second type of learning process results in developmental phenomena. Examples of both developmental and Ll transfer errors with liquids and glides are shown in the chart in Figure 5.5. English Ll Development (and L2 Leaming) L2 Leaming /r/ vs /w/ rabbit ➔ wabbit /1/ vs /r/ rice ➔ lice Japanese, Korean, and some East and Central African languages /1/ vs /w/ (line, wine) / lait/, /wait/ or / ait/ /wI vs /v/Wine ➔ vine Farsi (Iran) & Dari (Afghanistan) /f/ vs /wh/ fuji ➔ whuji /y/ vs /j/ yet ➔ jet Spanish /w/ vs / gw/ wet ➔ gwet Figure S.S. Developmental and Ll Transfer Errors. Minimal Pairs: Listening and Speaking When a learner has difficulty producing an English sound, an experienced teacher analyzes the error in comparison to the target pronunciation. For example a

- 14. student may say "I want a baby 'pick/JI instead of 1pig1 because in the Ll voicing of consonants does not occur word-finally. The words 'pig and pick' constitute a minimal pair, which consists of two words having two minimally contrastive sounds in the same position in a word. In the pig/pick example the word-final sounds are formed in the same place, and are both stops; they differ only minimally-in voicing. Figure 5.6 portrays pairs of words that do not constitute minimal pairs. 71 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language pick/pill The word-final sounds are not produced at the same location in the mouth and differ in terms of voicing. Also, /kl is a stop and /1/ is a continuant. trip/dip Although / t/ and / d/ are minimally contrastive, there is an extra sound, /r/. fight/night Rhyming words are not necessarily considered minimal pairs. Though they are both continuants, / f/ and / n/ differ in terms of manner (nasal vs fricative) and place of articulation. crutch/ grouch The velar stops/g/ and /k/ are minimally contrastive, but the vowel difference indicates not one contrast, but two.

- 15. Figure S.6. Non-Minimal Pairs Pause and Reflect 1. Study the pairs of words in Figure 5.7, say them aloud, and underline pairs that are mini- mally contrastive. Remember, only one contrast in the same position in both words constitutes a minimal pair. Don't be fooled by spelling. For example, the words in the first pair do not use the same spelling pattern, but they do constitute a minimal pair. buy/pie fan/vat catch/ glitch Sue/zoo rush/rouge bank/bag lip/lib than/thin tan/Dan fuss/fuzz cheap/jeep red/rent half/halve gum/come veal/feel puck/pug Figure S.7. Identifying Minimal Pairs in English. To listen to speakers of many different languages reading the same passage in English, go to this website: www.accent.gmu.edu, click on browse; click on any language, then find the list of speakers reading the same short paragraph. 2. In pairs or small groups, identify errors you heard and create minimal pairs to help the speaker(s) hear the difference between the two sounds. Consider consulting the consonant chart or your personal experiences in listening to Els

- 16. to complete this activity. There are two ways to assist Els with new sounds, through listening activities and visual pres- entations. A teacher begins with a listening, a minimal pair drill, which helps students hear the differ- ence between two sounds as in the case of the learner who says 'pick' for 'pig'. The teacher presents two minimally contrastive words orally so that the learner(s) can hear the difference. Figure 5.8 shows how to conduct a minimal pair drill to help Els distinguish between the sound /z/ and /s/. Once students can hear the differences, they are ready to say the words. You can use your hands, videos, or drawings of the vocal tract to demonstrate. Avoid drawing attention to your own mouth, as there may be taboos about doing so. There are numerous websites with lists of minimal pairs for teaching the sounds. Visit the ESOl website for suggestions. www.accent.gmu.edu - 72 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) Teacher: Student(s): Listen carefully as I say two words that sound similar, 'zap and sap'. (Do not show the words in writing.) Say slowly: They do not repeat, Zap, zap, zap, sap, sap, sap, listen only.

- 17. Zap,sap,zap,sap,zap,sap (Do not vary the intonation pattern as some will focus on tonal distinctions). When I say zap, put up one finger. When I say 'sap' put up two fingers. Say the words randomly and watch as students Students show fingers as show fingers, directed. ending the drill when students comply consistently. Do the same drill, but with the sounds in final or medial position: 'buzz, bus; phasing, facing.' Figure S.8. Leading a Minimal Pair Drill. The Systematicity ofEnglish Vowels Vowels are produced with no airflow obstruction, but always involve the tongue and vocal folds in their production. Among the simplest vowel systems is found in some dialects of Arabic, with only three vowels. Spanish has five, a very common pattern. 1. Study the five-vowel system chart in Figure 5.9 with the Arabic vowels shown in boldface type, as they are produced by moving the tongue in the mouth. Vowels change according to the vertical and horizontal position of the tongue in the mouth. ~ ~

- 18. 2. The Spanish vowel phonemes are pronounced as follows: /i/, as in 'neat', /e/, pronounced halfway between the vowels sounds in 'net' and 'Nate', /a/ as in 'not', /u/ as in 'newt', and/o/ pronounced halfway between the vowel sounds in 'note' and 'naught'. Pronounce the vowels and notice how your tongue position changes slightly as you move from front to back, then high to low in your mouth. Note that the labels represent the tongue positions. Tongue Front Central Back Position Tongue Height High Ii/ /ul lu/ Mid /e/ / of Low la/ Figure S.9. The Three-Vowel System of Arabic and Five-Vowel System of Spanish It should be noted that both systems are symmetrical. It is rare to find asymmetrical vowel sys- tems in languages. Just as you learned about consonants, you can see that vowels usually pattern in pairs. When examining the English vowel system, there is greater complexity but, still with vowels

- 19. 73 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals ofApplied Linguistics: Communication through Language in pairs, the distinction is between a tense or a lax tongue, as seen in Figure 5.10. For ELs who speak languages with few vowels, such as Spanish, there is considerable transfer of the system from the Ll, and this is often carried into late stage L2 development, even fossilized (permanently fixed) in late learners. However, for speakers of languages having many different vowel sounds, such as Vietnamese, English vowels present fewer problems. Those speakers are already attuned to distin- guishing subtle differences across their own vowel systems. Tongue Front Central Back Position Tongue Height Tongue Height Tense Lax Lax Tense High /i/ 'neat' / I/ 'knit'I /u/ 'nook' /u/ 'newt'

- 20. High Mid /ey/ 'Nate' /el 'net /A/ 'nut' hi 'naught' /ow/ 'note' Mid hi 'about' /£/ 'gnat' Low /a/ Low 'not' Figure S.1 0. The Vowel System of English. You have probably already noticed that the /r_/ sound in 'gnat' lacks a partner. Similarly, /a/ as in 'not' stands alone. Because the chart distorts the actual shape of the mouth, as you can see in the vocal tract diagram in Figure 5.3, the larger space in the high front

- 21. and central areas can simply accommo- date more sounds than can the central and low back space, thus the asymmetry of the system. What makes English vowels difficult to focus on is that speakers of different regional or social dialects produce diphthongs rather than simple vowels in some contexts, or they produce simple sounds rather than diphthongs in other contexts. For example, many speakers from Brooklyn in New York City produce / u"/ instead of hi in 'coffee'; speakers of some Southern dialects produce / a/ instead of / ay / in 'sight'. Of course, dialect differences are even more profound across the English-speaking world ofBritain, Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. But speak- ers of English as their first language exist in many of the former colonies in Africa and Asia as well; thus, this greatly expands the possibilities of standard pronunciation across the English language. The concept of World Englishes was developed by Braj Kachru (1990, 2006), who argues that the notion of a 'standard' dialect of English must be expanded beyond the core English-speaking area. Suprasegmentals Phonemes are not the only focus of interest in the field of linguistics. Tone, intonation, pitch, length, and stress, called suprasegmentals, are other properties ofpronunciation that affect accent and other communication difficulties experienced by ELs. According to Hudson (2000) these sound qualities occur, not at the phonetic level, but "spread over more than one phone" (26). Also called prosodic phenomena, these are length, stress, and pitch.

- 22. 74 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) Pause and Reflect 1. Now study the vowel system of English with its tense and lax vowel pairs, simple vowels, and diphthongs in Figure 5.10. 2. As you do so, note the key words in each position; say each word and listen to the very subtle difference between the two phonemes in each tense/lax pair. 3. Holding one hand, palm up, and pretending that it is your tongue, relax it, then tense it a few times. Pronounce the two words in each tense and lax pair as you relax and tense your hand. This kinesthetic activity is an effective way in helping Els feel the difference between the two sounds. Phonemes Minimal Pairs Examples /ii neat feel, teach, meat, cede, people, receive, believe, /I/ knit sit, mix, pick, film, rid, build /ey/ Nate bait, rate, plain, may, weigh, favor bait, rate, plain, may, /e/ net weigh, favor bet, said, rent, fence, bread

- 23. /El /a/ /u/ gnat not newt tack, sap, fan, magic mop, father, calm, sock, Tom, jolly luke, tune, fruit, room, blue, fool, tour, move, do, two, blew /u/ /owl nook note look, put, foot vote, poll, coat, broke, holy, so, sew, Roman, sold, though, low, beau hi naught caught, song, crawl, fought, ball, paw Figure 5.11. The Pronunciation and Spelling of English Vowels and Diphthongs. 75 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics:

- 24. Communication through Language Phonemes Minimal Pairs Examples /A/ nut sun, luck, mother, enough, rung hi/ noise toy, moist, Freud, foyle /aw/ noun round, house, cow, now /ai/ night fight, kind, mine, type, sign, fry, buy /ar/ narc farm, park, sorry, heart, /Ar/ nerd clerk, bird, learn, worry, first, hurt /or/ norm storm, for, tore, born, boar Figure 5.11. The Pronunciation and Spelling of English Vowels and Diphthongs. (Continued) Pause and Reflect 1. The chart in Figure 5. 11 illustrates the system, the key words as minimal pairs, and other words having the same vowel phonemes as each key word. Pronounce each of the words again, and note the additional diphthongs and the words influenced by /r/. Note the move- ment of the tongue from one position to another as you produce the diphthongs. 2. Discuss with a partner or in a small group the reading, listening, and speaking difficulties you might expect Els to face given both the subtle tense/lax differences and the spelling

- 25. variations. 3. Devise ways to help Els confront the realities of learning English pronunciation of vowels, using your knowledge of the specific difficulties experienced by l 1 speakers of languages you know. Phone lengthening can be a natural occurrence, demonstrated by the words 'hat' and 'had'. If you say these two words one after the other a few times, you will notice that the vowel sound is slightly longer in 'had'. The same occurs with'cab'/'cap','fuss'/'fuzz', 'half'/ 'halve' and 'bag'/'back'. As you may have discovered, this subtle lengthening occurs when the final consonant is voiced. In some lan- guages however, there is a phonemic difference between 'short' and 'long' vowel sounds. For exam- ple, in Swahili there is a phonemic difference between the words 'choo' (toilet), and 'cho' (a locative 76 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) particle within a verb). Vowel length produces a difference in meaning, though the vowel is produceci in the same place in the mouth in both words. ELs who speak languages having the lengthening fea- ture might be taught to use lengthening, a case of positive transfer, if they have difficulties with word- final devoicing. As American teachers well know, the terms short and long vowels refer to differences in sound, not actual vowel length, so they will need to help their ELs understand the difference.

- 26. Stress, "the intensity or loudness of the airstream" (27), occurs at the syllable level. In the fol- lowing three-syllable English words the stress occurs on different syllables in each one: Canada (1s: aroma (2nd), disappear (3rd ). The underlying rules of syllable stress are complex and can be difficU:.: to master. Many languages of the world have more regular stress patterns, such as Spanish where stress on most words is on the next-to-the-last syllable. Other languages, such as Japanese, haYc minimal syllable stress. For such speakers, learning the various possible stress patterns of Eng~ can be a daunting undertaking. "Pitch is the frequency of vibration of the vocal folds" (27). More frequent vibrations produce 2. higher pitch. Patterns of frequencies at the phrasal or sentence level are called intonation. In Eng- lish, falling intonation sentence-finally is often associated with statements, rising intonation wit:- yes/no questions. Saying the same phrase such as "we don't" using several different intonatio:- patterns results in subtle meaning differences. The rising and falling intonation patterns of Eng~ statements and questions are not universal; so, ELs benefit from some direct teaching of these pa:- tems. Tonal languages are those where a difference in pitch on a vowel in a syllable represents a:- altogether different phoneme. Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, Lao, and some African and Scandanavia:- languages are tonal languages. Vietnamese, a mono-syllabic tone language, has a high tone, a lo, -

- 27. tone, a falling tone, and a contour (rising/falling) tone. Changing the tone of a syllable produces c. difference in meaning. In Mandarin Chinese, the word 'ma' means scold when pronounced with c. falling tone, and 'hemp' when pronounced with a rising tone. Speakers of tone languages may bE able to transfer their sensitivity to tones to learning English intonation patterns. Phonology and Second Language (L2) Learning In sum, monolingual children acquiring their first language (Ll ) are capable of mastering any soun~ of any language; they are not born with the sounds of their parents, but rather with the capacity tr- acquire those sounds. We use the term acquire to refer to subconscious learning. Children are no: really taught language; they 'pick it up' from the linguistic environment of their homes. If childre::'. grow up in a bilingual or trilingual environment, they acquire all the sounds of the languages the:- hear and begin to speak. If children are in the environment of a new language in school, for example they will experience interference or transfer from the home language at first. But because the br~ of children before puberty are quite flexible, they generally lose their accents early in the language learning process. If individuals meet a new language after the age of puberty, however, it is quite likely that first language effects will occur in the way they speak the new language. Spanish speak~ learning English, for example, may have difficulty producing the difference between the / i/ in 'bee: and the /I/ in 'bit, orbetween the initial sounds in'cherry' and 'sherry'. They will almost always haYE

- 28. an accent from the Ll, although over time the accent may move closer to that of a native speaker o: the target language. Morphology As was discussed in the phonology section, languages have sound systems and these systems arE uniquely language-specific, but sounds themselves are not associated with meaning. Morpholo~ is the study of words and word forms and the processes by which words become created anci modified. Morphology does not entail the study of word meaning, but of word form and functio,: Words and word parts are stored and accessed from the lexicon, where they are associated witl-. meaning studied in the field of semantics. Morphemes Teach-er-s Non-lexicalLexical Teach- 77 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Classification ofMorphemes Figure S.12. Morphology. Morphemes are the smallest units of meaning in a language. Note the etymology of the word mor-

- 29. phemic: morph (form) and -emic pertaining to language specific phenomena. This is parallel to the term phonemic, pertaining to a language-specific sound. A classification of English morphemes is shown in Figure 5.13 with examples. Morphemes Free ( occurs alone) Bound (occurs with A free morpheme or other bound morpheme[s]) Lexical (content words) Non-lexical (grammatical or functional words) Lexical Stems/roots Non-lexical Derivational Non-lexical Inflectional book, family,

- 30. pleasantness and, only, of, now, our -vis- (invisible) -volv-, volu- (revolution) -ish (bookish) -ness (bookishness) -s (books) -ed (booked) Figure 5.13. Classification of English Morphemes. Lexical items, also called content words, include nouns, verbs, and adjectives, the traditional parts of speech. Although for most languages the characteristics of meaning are similar, the formal characteristics are widely varied. Some languages, such as Vietnamese, are monosyllabic, so infor- mation about number, tense, and the like occurs as separate morphemes. Thus, identifying and dis- tinguishing among parts of speech is difficult for ELs without morphological marking in their Lls. Yet, form and meaning characteristics of the lexical categories for English are fairly well-defined, as shown in Table 5.1 (with characteristics from Hudson, 2000). ,..

- 31. Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) 78 Table 5.1. Lexical Morphemes (Parts of Speech). Parts of Speech Formal Characteristics Meaning Characteristics Nouns: (many) can be pluralized: -s are usually names of animate puppy, house, imagination, puppies beings, events, places, concrete birthday, Tallahassee (some types) can be made objects, or abstract concepts possessive: -s puppy's bone can be made definite (with 'the' or indefinite (with 'a') can be made negative with prefix (non-believer) Verbs: can be marked for tense (cook~ usually express actions, being, cook, take, identify, become, is/ coo keg) or aspect ( cooking, states of being are, reside have cooked) can add suffixes to indicate agent (bak§:, pianist) can be made negative with prefix (disagree, misunderstand)

- 32. Adjectives: can be marked with -(i)er word- often modifies nouns or noun tall, round, hungry, beautiful, finally to indicate contrast, phrases interesting and with -(i)est to indicate superlative can be used with 'more' or 'most' can occur after 'very' or other intensifiers 1. You have probably noted that meaning characteristics described suggest that there are exceptions to the 'rules'. Identify ways in which some modifiers and some actions can be nouns and some nouns can be actions. 2. Can you add any formal characteristics to any of the lexical categories? 3. Another characteristic of the three lexical categories (also called open class words) is that new words are added to lexicon all the time, and some words drop out over time. Go to the Internet and search for obsolete words, as well as new words in the English language. Not all words are lexical; that is, not all have both formal characteristics and meaning proper- ties. A limited number of words "express a grammatical or structural relationship with other words in a sentence" (Nordquist at http:/ /grammar.about.com/od/fh/g/functionword.htm). These

- 33. words belong to a closed class. No new words enter this class; they have only one form, and they do not change over time. Non-lexical or functional morphemes in English include prepositions (of, to), determiners (the, a), temporal adverbs (now, soon), conjunctions (but, and), pronouns (we, them), auxiliaries (be, have), modals (can should) and quantifiers (some, both). Although many prepositions do have lexical content, and they pattern like nouns, verbs, and adjectives at the phrasal level; they are often placed in the non-lexical category because they behave like other closed class words in lacking formal characteristics, not changing over time or increasing in number. https://grammar.about.com/od/fh/g/functionword.htm 79 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Derivational Morphemes Derivation is a process involving the addition of a bound morpheme, called an affix, to the beginning or ending of an existing word. Derivational affixes are both prefixes and suffixes in English (although some languages also have infixes).* Examples of prefixes and suffixes are found in Tables 5.2 and 5.3 respectively. Note that Table 5.2 shows that a prefix retains the grammatical category of the root word, but changes its meaning. Prefix Change of meaning Examples ex- former ex-wife, ex-boyfriend

- 34. deactivate, deconstruct disappear, discontinue, dislike de- not, or opposite opposite dis- mis- wrong misunderstand, misrepresent re- again reconsider, redo un- reverse action, or not uncover, unlock, unreliable inconvenient, impossible -in/-im not -con -sub with convene, conduct under submarine, subterranean Table 5.3 shows that a suffix changes the grammatical category (form) of a word, but retains its meaning. This distinction holds for most cases. Learning derivational morphemes is difficult for second language learners, especially for those whose languages lack prefixes and suffixes. But because these morphemes are taught to native speakers as part of the language arts curriculum, elementary, language arts, and English teachers already have effective ways of teaching them.

- 35. Table 5.3. Suffixes, Change of Grammatical Category, and Examples. Suffix Change of Grammatical Category Examples -able Adjective from Verb movable, doable, readable -ing Adjective or Noun from Verb reading (class), moving (target), moving is hard, swimming is fun -ive Adjective from Verb impressive, subjective -al Noun form Verb refusal, denial, arrival -ant Noun from Verb defendant, applicant, informant -dorn Noun from Noun or Adjective kingdom, freedom -ful Adjective from Noun fearful, hopeful, stressful, blissful -ous Adjective from Noun poisonous, ruinous -ize Verb from Noun or Adjective capitalize, hospitalize, polarize, nationalize -en Verb from Adjective blacken, harden -ly Adverb from Adjective slowly, lightly -ity Noun from Adjective superiority, priority, ability • Tagalog, a language spoken in the Philippines uses infixes. For example -um is the infix to form the infinitive of a verb; sulat (write)-sumulat (to write)

- 36. 80 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) Roots and Stems Not all bound morphemes are affixes. Some originate in Latin or Greek languages, from which a very great number of English words have been borrowed, often through French or Middle English. These stems or roots are bound lexical morphemes and they form the primary meaning of a word. Although some are words in their own right, others are not, as shown in Table 5.4. A number of resources are available to promote rapid and systematic vocabulary development for ELs, among them dictionaries and texts specifically devoted to stems and affixes. However, since ELs may overgeneralize their knowledge of a particular root or stem and misunderstand the word's meaning, educators should provide counter-examples to support learning. Table 5.4. Latin- (L) and Greek-(G)Based Stems/Roots. Stems/Roots (language of origin, meaning) Examples -port- (from L. portare, carry) transport, export, portable -due- or -duct- (from L. ducere, lead) conduct, deduct, produce, educate, inductive -vis- (from L. videre, see) visage, invisible, visionary, visitor, revise -volve-, -volu- (from L. volvere, roll) involve, revolution, voluble -cred- (from L. credere, believe) incredible, credulous, credit, credential

- 37. -fin- (from L. finir, end, conclusion) finish, infinite, refined aero- (from G. akros, topmost, extreme) acrophobia, acrobat, acronym Inflectional Morphemes Some of the world's languages have a great many inflectional affixes. Romance languages such as Spanish, Italian, and French use suffixes to indicate gender (masculine/feminine) and number (singular/plural) on nouns; determiners and adjectives must agree with their corresponding nouns by adding the same suffix, as shown in the following sentences in Table 5.Sa. These languages also indicate number, person, and tense on verbs using suffixes, as shown in Table 5.Sb. Table 5.Sa. Spanish Nouns: Number and Gender Agreement. El libro esta verb en preposition la determiner mesa. noun Determiner noun (masculine, (masculine, (feminine, (feminine, singular) singular) book

- 38. libros is located est.in on singular) the singular) table The Los en las determiner mesas noun Determiner noun verb preposition (masculine, plural) (masculine, plural) (feminine, (feminine, plural) _Elural) The books are located on the tables. Table S.Sb. Spanish Verb (hablar, to speak), Person, Number and Tense Marking. Present tense hablo(lps) hablas(2ps) habla(3ps) hablamos(lpp) hablais(2pp) hablan(3pp) Preterite tense (past) hable hablaste habl6 hablamos hablasteis hablaron (Note: ps=person singular; pp=person plural) (http:/ /www.studyspanish.com/lessons)

- 39. 81 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Pause and Reflect 1. Elementary teachers: With a partner or in a small group, address the issues in this scenario: You have a class with Els some of whom speak Romance languages, but several of whom do not. How would you organize instruction of a unit on derivational morphology that would be fair for speakers from both backgrounds? What learning aids or activities would you assign to help Els learn these morphemes independently? 2. Language arts teachers: You have strategies and resources for teaching root words and affixes. Suggest ways you might augment your teaching of these affixes for Els. 3. Secondary teachers: All academic areas utilize affixes as well as root words. List several examples in your academic content and suggest ways you might help Els to learn them. Swahili and other Bantu languages spoken across much of Africa make use of even more affixes on nouns and verbs, as demonstrated in this example: Tulimwendeshia Dar es Salaam garini letu in Table 5.6. We drove him to Dar es Salaam in our car. Prefixes and infixes precede the verb stem (go), while suffixes augment the verb's meaning. Modifiers of nouns must agree with their noun classes,

- 40. or genders, of which there are several in Bantu languages, most having singular and plural forms. Table S.6. Explication of Swahili Sentence Tu- -li- -m(w)- end(a)- -eshia Dares gari- -ni 1- -etu Salaam lps past 3ps go cause to car in Agr, li/ lpp our We him/ ma her class sing For English speakers, the rich inflectional morphology of suchlanguages is usually quite difficult to learn because English makes so few distinctions. So, should learning the English system be easy because of its few inflectional morphemes? Unfortunately, it turns out that inflectional morphemes are quite problematic for ELs, so teachers must be aware that inflectional morphemes need to be given a lot of attention. The chart in Table 5.7 lists these morphemes. 82 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) Table S.7. Inflectional Morphemes of English. Part of Speech Morphemes Nouns Plural -s the cars; Possessive -s Mary's car Verbs 3rd Person Singular -s; Mary likes you.

- 41. Present Participle -ing; Mary is reading. Past -ed; Mary liked the book. Past Participle -ed/-en; Mary has cooked. The eggs were broken. Adjectives Comparative -er big - bigger Adverbs Superlative -est big - the biggest -ly slowly, quickly I Developmental Phenomena in L2 Learning To explain why these morphemes are so difficult for learners of English, we must look at the facts of a child's first language development. As you have read, in addition to Ll transfer as a factor in L2 learning, learner errors can also be due to the complexity of the target language. All L2 learn- ers, like child Ll learners, produce developmental errors that arise when encountering difficult aspects of a target language. Research conducted with Spanish and Italian children learning thei: first language showed that they acquire the functions and forms of tense, person, gender, and num- ber marking earlier than English speaking children learn their inflectional system with far fewer morphemes. This is because of the regularity and salience in the inflectional systems of Spanish and. Italian. Although some verb roots display irregularity with and across tense and aspect, the ending5 (-o, -as, -amos, etc.) do not change. Note also that those endings are perceptually salient; that is, eacl-.

- 42. one is an added syllable at the end of the verb root. It is easily heard; each suffix either is a vowel, or begins with a vowel, so it is processed easily. The learnability of the Spanish and Italian systems is less complex than that of English. Slobin (2007) and others analyzed the learning sequences of gram- matical morphemes by children from many different language backgrounds and have suggested a number of cognitive principles to explain ease and difficulty of learning. The learnability rule is a two-part explanation of why Spanish and Italian inflectional systems are easier to learn that of English. Part A: One form to one meaning is learned earlier than one form to man: meanings. With reference to Table 5.7, the inflectional morpheme '-ing' has one function,; the presen: participle indicates the progressive aspect. It also has one invariant form and is learned early. On the other hand, when spoken, the morpheme'-s' ( one form) can indicate three different functions: a plura:. a possessive, and a third person singular verb. Though the plural form is learned somewhat early, the other two are late. Similarly, the morpheme '-ed' has two functions, to mark the regular past tense anc. to indicate the regular past participle form, which can be used with both the auxiliary 'have' and 'be forms, in the case of the perfective aspect and the passive voice respectively. Again, native English- speaking children learn these forms late, especially the past participle form. These developmental fa~ about verbs are made more difficult by the existence of both regular and irregular past and past parti- ciple forms. It is often surprising to hear English-speaking children produce common irregular ver~ before the regular forms. This is because the '-ed' form, as in

- 43. 'worked' or 'finished' is not as perceptual:: salient as an irregular form, as in 'broke' or 'took'. The fact that two stop consonants occur together at the end of the word is very difficult for man~- non-native speakers whose languages do not allow such clusters; the / t/ ending, as in /workt/, ~ not salient. As for verbs like 'need' and 'plant' (those that end in / t/ or / d/), adding -ed creates an extra syllable, making the ending salient. In fact, when learning to read English aloud, man:- learners overgeneralize the /Id/ form, producing' /laikld/ (lik- ed) or /muvld/ (mov-ed), assum- ing these verbs pattern with /nidld/ (needed). Although for learners the '-ed' form is usually no: salient, the irregular forms are. 83 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Pause and Reflect 1. To understand the concept of perceptual salience, pronounce the words 'like' and 'liked' to yourself. Note that both have only one syllable and that the /t/ follows /k/, forming a cluster of two voiceless stops. 2. Why do you think the /t/ is difficult to hear in rapid speech? For example, learners might produce "I broke it" or "I ate it" before they produce "I pushed it" or "I cooked it." Later, when they begin to understand the function of'-ed', they overgeneralize with

- 44. irregular verbs, producing such utterances as "I breaked it," "I broked it," or "I eated it." Language learners, noticing that recurring patterns are found in language, create rules to apply to new situa- tions. They use these rules all the time; generalization is a highly effective process in learning. Edu- cators must recognize that learners have created a rule when they overgeneralize, or extend the rule. Part B of the learnability rule is that one meaning to one form is learned earlier flum one meaning to many forms. A good example pertains to the pronunciation of the past tense '-ed' endings of regular verbs. Table 5.8 lists examples of this language phenomenon at the intersection of phonology and morphology. Table S.S. Regular Past Tense Verb Forms. liked fixed missed jailed picked buzzed banned inferred laughed moved begged finished dropped freed formed watched lobbed judged hanged stayed (V 9 Pause and Reflect 1. With a partner or in a small group pronounce the regular past tense forms in Table 5.8, and note whether you produce /t/ or/d/ for the regular '-ed' ending. Do not distort the pronun- ciation, but produce it as you would in normal conversation.

- 45. 2. Put the verbs into either a /t/ list or a / d/ list; then, explain your reasoning. Hint: Note the voicing of /t/ and /d/. 3. Do you think native English-speaking children have to learn how to pronounce these verb endings correctly? Or does this come 'naturally' to them? 84 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) d,Je 5.10. Sentence Types . .~--=:nr~-itic:e Negative Yes/No Wh- question Emphasis Tag question Passive question -~ buys groceries Ari doesn't Does Ari buy Where does Ari does buy Ari buys A lot of buy groceries Ari buy groceries in groceries groceries □ Tampa. groceries in Tampa? groceries? Tampa. in Tampa, are bought in Tampa. doesn't he? in Tampa. :.-.c ··o..:::- ~O".!: ~ - ~--.-..- ......... ,.,;- ~ _;...,;,., -

- 46. ~crru.a~ -.e: :a:-..g For ELs, particularly adolescents and adults, learning three separate morpho-phonemes for the -ed' ending (the It/ in 'liked', the /d/ in 'loved', and the /'-Id/ in 'needed') presents the one mean- :ng, many forms learning problem. English-speaking children probably pick up this pronunciation 2asily - they do not have to be taught how to do it. You may recall from the phonology reading :hat some languages have a 'devoicing' feature on consonants at the ends of words, or have no consonant clusters, or lack voiced stops or fricatives word- finally. So, it is clear that learning to hear, then produce these endings will probably take some focused explicit instruction. Note that the plural-s morpheme also has three forms: /s/ as in 'pipes', /z/ as in 'cars', and /Iz/ as in 'churches'. The following minimal pairs of noun plurals can be used to help learners hear, then produce the voiced/voice- less distinction: pigs/picks, buzzes/buses, mates/maids, calfs/calves, mobs/mops. In sum, in the case of one mean- ing/many forms, first language effects join with develop- mental effects to produce significant learnability difficulties. ::::: Problems in English Verb Morphology Co~ared to Spanish, the English inflectional morphological system is 'impoverished, there being :e'•,- endings or auxiliaries included in the English verb phrase. However, the system can be quite :::.ii.'.ficult for all learners and may not be mastered at all by

- 47. non-native speakers. In fact, the order 0: learning English morphemes forms the basis of a claim (by some second language acquisition :-oe.archers) that developmental phenomenon, as opposed to transfer, better predicts the production Gf :-1 English inflectional morphology across time because of its complexity. a:ble 5.9. Auxiliaries and Modals and their Functions. I' re used with have used with do used with modals used with I a::-.., is, V + ing; have, V + -ed or do, does, V (unmark-ed) can, will, V (unmark-ed) a.re, progressive has, -en did does eat, did shall, can see, might ~.• •asl running, had cooked, go could, go ;;·ere eating eaten, would, V +-ed or -en broken should, Passive may, are seen, i§ might, eaten must, ought to Tne lists in Table 5.9 portray the auxiliaries (helping verbs) of English, the forms of 'be', 'have', .::n .and the modals in columns 1, 3, 5, and 7 respectively, with the verb forms they 'help' in columns :. ..;,, 6, and 8 respectively. Each of these (usually) behaves in the same way in affirmative statements, ?~es::ions (yes/no, wh-), negative statements, emphatic statements, tags, and passives. Table 5.10 portrays seven main sentence types using the 3<<l

- 48. person verb 'buy' in the present ::c:-.se. ::-(ote how the verb is altered across the sentence types. j_ 3. - 85 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Pause and Reflect 1. Describe what happens to the verb with each type, particularly the placement of the auxiliary or modal in question formation (linguists call this aux- movement). 2. Change the same verb to the past tense for each sentence type and describe what happens. 3. Try completing the seven columns of the chart with the 1st person present perfect aspect of the verb; for example, 'We have already eaten lunch.' and the verb with a modal, for example, 'They should finish by noon.' and the 2nd person past progressive aspect of the verb, 'You were running the race.' What differences in the patterns do you observe? In sum, we have learned that morphemes are the smallest meaningful units of a language, that :hey can be free or bound, and that bound morphemes are either derivational or inflectional. Deriva- :ional morphology is taught in language arts curricula because

- 49. all students need to understand and :ise the morphemes. But students whose languages lack derivations may need more explicit instruc- :ion; L1 effects occur because such morphemes are absent in the Ll, not because something is dif- .:erent. Inflectional morphology is quite problematic because of both Ll and developmental effects. :-he basis for this claim is to be found by examining several examples of the leamability rule: in the sequence of learning for all learners of English one form/one meaning precedes and is easier than one form/many meanings, or one meaning/many forms. The examples should guide teachers to become more aware that L2 learning often needs a boost °:)ecause of Lleffects, developmental effects, or both. Some theories of second language learning pro- :note the idea that input alone is enough to initiate the process and keep it going 'naturally.' How- e·er, errors in reception and production may persist if not addressed early on, especially for all but :he youngest learners. Whether you agree with the habit formation theory or not, explicit instruction about English morphology and its phonological manifestations is essential for all students. Syntax :n 1959 Noam Chomsky, the most important linguist of the 20th century, challenged the claims of 3. F. Skinner, a noted behaviorist, that language learning can be explained as a series of stimulus/ ~ sponse events. Chomsky presented an alternative idea, namely that language is innate, and that ~anguage learning, or acquisition, is possible because a child is already predisposed to activate his/

- 50. ier language organ. Over the years Chomsky and his followers, using data from many different - 86 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) languages, have developed and constantly revised a theory to explain an innate disposition for language, and what was once referred to as the language acquisition device (LAD). These linguists prefer to use the term acquire, as opposed to learn, to refer to subconscious processes that occur during the early years of life. Chomsky's major work focuses on the structural level of language called syntax, which entails the units beyond the word level- phrases and sentences. Theoretical Issues with Syntax So far in this chapter, you have read about phonology, the sound system, and morphology, word forms and functions. These systems are also structural components of language; they are systematic and rule-governed, as is syntax. It is important to point out that Chom- skians attempt to understand language more at the level of structure than of meaning. Meaning, as well as communication, he has claimed, should be beyond the purview of structural linguistics.

- 51. In any language, a sequence of words may represent a sentence. But a sentence in a lan- guage cannot simply be just any sequence of words; it must conform to the rules underlying it. For example, the rules of English syntax do not generate, or describe, the sequence 'girl book see.' The elements are out of order, the verb does not indicate tense or number and articles are missing. Native speakers are able to recognize word combinations that violate these rules as ungrammatical, thus incorrect. This is not necessarily based on a speaker's familiarity with prescriptive language rules, but comes from knowledge often outside of awareness, acquired as we grow up. Moreover, the grammaticality of a sentence is not necessarily linked to meaning. Chomsky's (1957) famous sentence colorless green ideas sleep furiously doesn't make sense, but it conforms to the correct ordering of English and illustrates the separation of grammaticality and meaning. Lexical and Functional Categories In order to analyze the structure of phrases and sentences, a review of word-level categories is essential. Languages have two major groups of words: lexical and functional . These categories are listed in Table 5.11 (or refer back to Table 5.1). Linguists assume that all languages have the same categories. Functional categories are listed in Table 5.12. Universals in Word Ordering What is important about these categories of words is that in any given language they are ordered in specific ways; this is a universal aspect of all languages. The ordering rules of English word

- 52. order are quite strict, and the order subject/verb/ (object) (SVO) is the canonical, or typical, order (The object category is parenthesized because not all sentences have objects). However, SVO is not the only possible word order, though it is widespread throughout the world, espe- cially in Western Europe. Languages of Korea, Japan, North Africa, and the Inda-Iranian family are predominantly subject/ (object)/verb (SOV). Verb-first orders are less common (though they include Arabic and several Celtic languages); object-first languages are rarer still, with American Sign Language (ASL) being among the very few of the OVS type, and Klingon the only OS" language. 87 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Table S,11. Lexical Categories. Lexical categories Examples Noun book, city, girl, the playground, idea Verb write, read, sing, become, live, be Adjective lazy, slow, large interesting, young Preposition on, under, to, of, at Table 5.12. Functional Categories. Functional category Examples

- 53. Determiners (Det) Article Possessive Demonstrative a, the her, our this, those Auxiliaries (Aux) Modal Non-modal will, can, may, might, must, could, etc. be,have,do Conjunctions (Con) and, or, but Degree word (Deg) too, quite, only, etc. Pause and Reflect 1. Create some sequences of words that do not constitute a sentence, and any other sequences that 'obey the rules' of English, but do not make sense. 2. Because Els come from a variety of L2 backgrounds, not all of whom share the English word order in sentences, they benefit from tasks that require putting words in the correct order. You can cut up sentences and mix the words from each sentence so that students can reassemble the sentences. Or you can provide specific Apps to support Els' learning by going to the ESOL website for suggestions.

- 54. Case-Marking In examining Japanese and Korean, we find that the word order may be a bit looser than it is in English. That is because in these languages nouns are assigned case according to their functions in the sentence, such as subject, object, possessive, instrumental, and so on. In each 88 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) .: .. situation a case marker indicates the function of the noun. For example, a grammatical sentence in Japanese might be expressed as 'boy' (subject marker) 'horse' (object marker) kick'. Or it might read as 'horse (object marker) boy (subject marker) kick'. Both sentences have the same meaning because the case, not the word order, indicates who is doing what to whom. Because Japanese is a head-final word order language, however, the verb must come last, no matter what the order of the noun phrase. The verb phrase is the core of sentence structure, and, as noted previously, there are two options for the majority of world languages: verb first (English) and Yerb last (Japanese). Although many of the world's languages have no case-marking at all, others have 10 or more. The most common case is nominative (subject); accusative (direct object) is also common. In

- 55. addition to Japanese and Korean, other case-marked languages are Latin, Slavic (Russian, Ukarainian, Polish, Czech, Bulgar- ian, Serbo-Croatian, etc.), Baltic (Lithuanian and Latvian), and Finno-Urgaic, (Finnish, Hungarian, Estonian). Luthuanian has 14 cases. Old and Middle English had case-marking on nouns, but Modern English retains case only on pronouns. Each per- son and number has subject, object, and possessive forms. For example the first person singular forms are 'I', 'me', and 'my' respectively; the third person plural forms are 'they', 'them', and 'their' respectively. These forms are usually learned late in first language acquisition, and may also pose difficulties for ELs. Most educators can only imagine that English speakers learning case-marked languages would find this aspect quite difficult. However, for speakers of these languages learn- ing English, the lack of case marking poses problems in ways that affect the ordering of phrases within an English sentence. Speakers of case-marked languages have the freedom to order elements to provide focus where they want it and do not neces- sarily follow a strict word order. The following examples from a narrative about a naughty baby owlet told by a native bilingual speaker of Russian and Czech, both case-marked languages, demonstrate this difficulty. Note that me speaker, Natasha, places focused information at the end of the sentence in ways different from ;:he way the information would be placed by English speakers. 1. And then first egg, braked and was born Frankie. And afterward second, from second egg was born Marushka. And after another while was born, Bedjik. 2. When she wanted to show her husband their new babies, it was in the bed only Frankie and

- 56. Marushka. 3. After summer start school. 4. After this movie Bedjik played with Marushka and Frankie that he is bandit and he wants to shoot them. .:>. Marushka and Frankie saw ... that came, and spoke with Bedjik this big animal, red animal Lishka (fox). 6. And Lishka saw that he is so non-educated and he doesn't know who she is and then she w ants to play with him game. 1. After carefully examining the ways in which Natasha orders her sentences, imagine that she is a student in your classroom. With a partner or in a small group, discuss ways to help Natasha with word order problems (ignore for the moment some other problems such as omission of articles). 89 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language Order of Elements in Phrases A very interesting aspect of languages is that by and large the noun, verb, adjective, and prepo- sitional phrases usually follow the same pattern. For example, in the English verb phrase 'kicked :he horse', the verb precedes its object, while in the Korean phrase 'horse (object marker) kicked',

- 57. :he verb follows the object. The verb is called the head of the phrase, and its object is called a com- plement, because it completes the phrase (phrases may also include specifiers which function to make the head precise*). At the very least, the obligatory element in a phrase is the head. There can- not be a phrase without a head in its category. Examining the other phrases in English or Korean, we find that all phrase types follow the same order as the verb displays. The examples in Table 5.13 illustrate how specifiers, heads, and complements are ordered in English. Pause and Reflect 1. Using a reference, or based on your own experiences, construct a chart of phrases from another language similar to those in Table 5. 13. Table 5.13. English Phrase Structure, Head First. Phrase Types Specifier Head Complement >Joun Phrase (NP) The A boy pig wearing a tie Verb Phrase (VP) operates goes a machine

- 58. Adverb Phrase (AP) very clean hard as a rock Prepositional Phrase (PP) just under around the trees the comer Although basic phrase structure word orders for most languages are either head-first or head-last, rules for arrangements within these basic structures may be more complicated. For example, exam- ine the string of words in Table 5.14 and place them in grammatical order. Table S.14, Complex NP. ICereal IThose IYellow IBowls ILarge IThree This string is not a sentence, but a noun phrase with several adjectives. Begin by identifying the noun that is the head of the phrase. Native English speakers almost always agree on the order, but often cannot explain the 'rule' that describes it. When given this string of words to put in order, non-native speakers experience difficulties because ofits complexity. This example demonstrates that as the second language (L2) develops, all learners have to deal with ways in which English is challenging to learn. * Specifier type is determined by the phrase head. For example, in the noun phrase (NP) 'the book' the specifier can be a determiner (Det), in this case 'the'. But an adverb cannot be a specifier in an NP: 'slowly book' is not grammatical.

- 59. ___ _ ?O Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) d® Pause and Reflect .._, l. Now that you have seen how English orders phrases, translate each of the words in the phrase above into Spanish or another language you may know. 2. Arrange them in their correct grammatical order. Is the order the same as that for English noun phrases? Do you have to add any words to make a good translation? 1. Construct similar examples based on the same pattern. 2. When you recognize what kinds of adjectives occur in which position, create a chart like Table 5.13 and label each column to show the order of the various types of modifiers. ELs will not always have a 'feel' for the correct order, and will need to be taught. By providing a 5eneralized ordering rule, teachers will be able to guide students in overcoming English word order ;:ii.-=ficulties. You may have noticed that the head of the noun phrase comes, not at the beginning, but a': the end when this string of words is put in order. This is because single word adjectives occur

- 60. ::-eiore the noun in English, while adjectival phrases and clauses follow the noun, thus preserving ::.."-le normal head-first phrase structure pattern. When students see several examples of the same pattern, they can recognize, and later follow, ::..'--;.e rules to create a well-ordered phrase. Verb, adjective, and prepositional phrases may also be complex, so learners need practice putting them in order as well. Prescriptive Grammar Rules K."owledge of English word order is typically not taught in American schools because native speak- 2r5 acquire it as children. More often than not, however, grammar is formally taught in foreign :.a....-1guage courses in order to present the structure of the language. Frequently the grammatical rules taught in upper elementary language arts and secondary English courses in American schools are prescriptive, rather than descriptive rules, those that portray how the language actually works. Many so-called 'rules' are actually quite old and were proposed by English grammarians based on a study of Latin. For example, the 'rule' do not end a sentence with a preposition works for Latin, but not for English. We accept "who are you going with?" even though the question ends with a preposition. Another incorrect rule is use a singular verb with a plural subject and a plu- ral verb with a singular subject. In examining the ....,, .....::.RuLcS (}) ___

- 61. (f)®·----- @ 91 Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language ;e.ntences in Table 5.15, you can see that the rule is not correct. Neither 'I' nor 'you', both singular, ::-equires the verb to be marked with '-s'. In fact, only one person (3rd) takes a so-called 'plural' verb. But, as noted in the morphology sec- jon, the '-s' does not represent a plural, but simply denotes the third person singular form of the ? resent tense verb. In older versions of English, verbs were marked for person and number, just as in Spanish and other European languages. Only the 3rd person singular form has remained in English. In some dialects of English it, too, is not used, and may someday disappear from English all together. All students need to understand how a language really works in normal spoken and written discourse. Table S.1 S. The third person singular rule. Person, Number, Singular Subject Verb Person, Number, Plural Subject Verb

- 62. 1st I read }'I we read 2nd you read 2nd you read 3rt1 he, she, it reads 3,ct they read In sum, linguist Noam Chomsky claimed that language is an organ, just as the heart and lungs are organs, providing us with an innate linguistic capacity that allows young children to acquire :canguage out of awareness. Because language is an organ, he argues, we are born with the capac- :ty to use the organ already partially pre-programmed, such as with the knowledge that language obeys certain ordering rules, with all phrase types (noun, verb, etc.) being consistently either head- :irst or head-final across the board. Korean children are not born with a head-last word order, nor are Spanish-speaking children born with a head-first order. Instead, as children hear their first :anguage, they figure out the phrase structure rules and apply them when learning to speak. With respect to second language learners, the ordering rules of the first language may produce :ransfer effects on later-learned languages, though they might not result in errors as transparent as those at the phonological level. In Natasha's case, the fact that her two Lls are case-marked allowed arrangement of elements less constrained than those of English. On the other hand, the example of the complex noun phrase (about the cereal bowls) illustrates that developmental effects are also at play. It takes a long period for such complex structures to be fully learned. It is important to note that the work of Chomsky, his students, and his other followers is formi-

- 63. dable inn its detail and depth of insight about the workings of language. Nonetheless, his theory has been challenged by other linguists, including developmental psycholinguists, whose data raise questions about the notion of a pre-programmed language template. Yet, no matter whose theory educators espouse, access to the right kinds of information about how languages really work in conversation and writing is essential. To appropriately and adequately understand and address ELs' needs, educators must acknowledge a variety of factors and different theoretical explanations. Semantics You have read about phonology (system of sounds), morphology (word forms and formation pro- cesses), and syntax (how words join to form larger units), and the three levels of language considered to be innate, according to the Chomskian perspective; the next two levels are semantics and pragmatics, both seen as learned aspects of language. "Semantics is the branch of linguistics thatdeals with the study of meaning, changes in meaning, and the principles that govern the relationship between sentences or words and their meanings" (http:/ /www.thefreedictionary.com/semantics). In this section, you will find information about the lexicon, ideas for teaching vocabulary, assigning vs. containing meaning, denotation and connotation semantic relations at word and sentence level, and ambiguity. Throughout this section are suggestions for discussion and for ways to assist English learners from PreK-12. www.thefreedictionary.com/semantics

- 64. 92 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) Experimental research has revealed that words are organized and stored in many different ways in the mind. For example, if you can't remember a word, you may remember its beginning sound, form a mental representation of the word (such as 'dog'), or locate the word according to its cat- egory. Table 5.16 provides a list of categories of word knowledge (Nation, 1990) which help to illus- trate how words are stored in the mental lexicon. Table 5.16. Types of Word Knowledge. Examples - deep Spoken form of a word Types of Word Knowledge /dip/ I d-e-e-p Morphemes possible Written form of a word deep (adjective); also depth (noun), deepen (verb), deep -er, -er -est (comparative, superlative forms) deeply (adverb) Grammatical behavior of a word The pool is deep (predicate adjective). He's going into deep water (adjective before noun). It's too deep for wading (adjective with specifier & complement).

- 65. Collocational behavior of a word (as) deep (as the ocean), often used with words pertaining to bodies of water or places below !!round Frequency of a word how often it occurs in speech or writing Stylistic register constraints; when a word is inappropriate to use It would be inappropriate to use slang or swear words when speaking with a person who is interviewing you for a job. Conceptual meaning of a word Representation of a small figure with a large amount of water, for example, beneath it. Associations with related words Deep: shallow (antonym), profound (synonym), far down in water or underground place (paraphrase) Table 5.17 provides a list of principles of vocabulary learning (Schmitt and Schmitt, 1995) whirr are also based on an understanding of the mental lexicon. Table S.17. Principles of Vocabulary Learning. 1. The best way to remember new words is to incorporate them in (into) to language that is already known. 2. Organized material is easier to learn. 3. Words which are very similar should not be taught at the same time. -!. Word pairs can be used to learn a great number of words in a short time . .J. Knowing a word entails more than just knowing the meaning. 6. The deeper the mental processing used when learning a word, the more likely a student will

- 66. remember it. 7. The act of recalling a word makes it more likely that the learner will recall it again later. 8. Learners must pay attention in order to learn more effectively. 9. Words need to be recycled to be learned. 10. Learners are individuals with different learning styles. Vocabulary learning in the classroom can be done in many different ways. Mendoza (2003) cre- ated suggestions for university level English learners based on her doctoral research. Some of these suggestions are well-suited for younger learners, as well as middle and secondary ELs. She advise.:: learners to make new words on their own in at least three of the following ways: a . draw a picture b. write a translation c. use it in a sentence d . write its part of speech Chapter Five: The Fundamentals of Applied Linguistics: Communication through Language ~- e. write its various forms f. write a synonym and an antonym g. say the word aloud several times h. use it with your friends i. put a new word list on a bulletin board or chart j. keep an alphabetized list of words in your notebook k. organize your words by topic or by part of speech 1. make a list of words with similar meanings

- 67. m. organize words according to their Greek or Latin roots n. locate a word in the dictionary and analyze its parts (prefixes, suffixes, roots). Pause and Reflect 1. Recall from the morphology section that all words, or lexical and non-lexical items, are free morphemes, and that word parts are bound. Explain whether you think bound morphemes are also stored in the mental lexicon w ith their meanings/uses, or whether they are stored with individual free morphemes. 2. For information about language and the brain, visit: http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu/ hurley/Ling 102web/mod5_Llearning/5mod5.1 _neuro.htm. What It Means to Mean: Do Words Contain Meaning? Early in thenineteenthcenturyinCentral Europe, semantics emerged as a separate subfield of linguis- tics to study meaning (http:/ /www.studymode.com/ essays/ The-History-Of-Semantics-1550608. html). According to the Western Rationalist position, meanings are not contained in words (or larger units), but are assigned to these units by speakers and hearers over time in public discourse. If mean- ings were contained in language, they would not change over time, although we know that they do. Similarly, because there are so many meanings assigned to some words in the lexicon, a single conceptualization can be difficult to pin down. For example, the meaning of run in 'run a race' is not the same as run in 'run a business'.

- 68. The core meaning of run is 'to move quickly on foot' because speakers of English understand it that way. Yet we might instead have started using the word 'bleb' (a non-word), or 'correr' (the word in Spanish) instead of 'run'. Specific words are simply arbitrary combinations of sounds that are assigned meanings by speakers. Whenever a new concept emerges, somebody names it, the name spreads, and soon it becomes a part of the lexicon of speakers. When a new edition of a dic- tionary appears, it contains these new words in the communal lexicon. Adults are able to distinguish between a word and its referent. Yet, developmental studies have shown that very young children do not always conceptually separate words from their referents. Some research has determined that bilingual children have an advantage over monolinguals in this regard. When shown a picture of the moon, told it is a 'bleb,' and asked if the picture is still of a moon, the very young monolingual English-speaking child will say "no." But because Spanish/ English www.studymode.com http://emedia.leeward.hawaii.edu 94 Part Two: Language and Literacy (Applied Linguistics) bilingual children of the same age have already learned that the moon can be called luna and moon, they are likely to say that the picture is still the moon, despite its being called 'bleb.' They know that two different words can have the same referent.

- 69. 6® Pause and Reflect l. With a partner or in a small group discuss ways you have observed vocabulary learning in the classroom. 2. Have you had success with any of the methods listed above? 3. How would you encourage Els to identify and use their individual preferences for learning new words? 4. Mendoza encouraged her students to personalize their vocabularies by dividing a 5x8 card into four sections and writi ng one of the options listed above on each section, as shown in Figure 5.14. How can the use of technology support this strategy? Definition and Part of Speech: credible (adjective), believable Use in a sentence: His story about the accident was not credible. I think he was lying. Translation: Words with same root: incredible, credit, credulous, creditor (from Latin, credere), accreditation Figure 5.14. Individual Vocabulary Learning Technique.