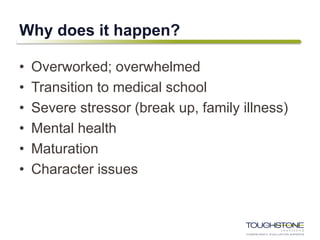

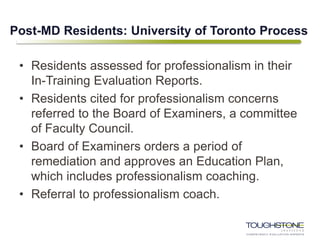

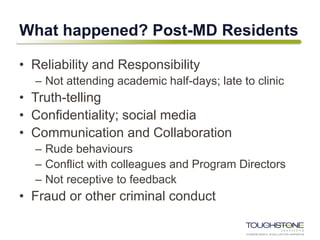

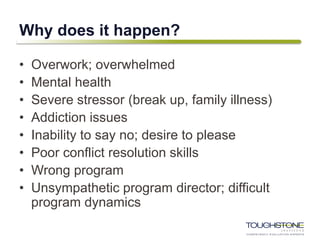

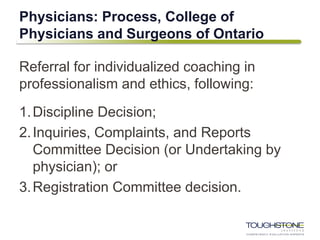

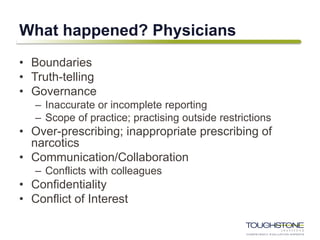

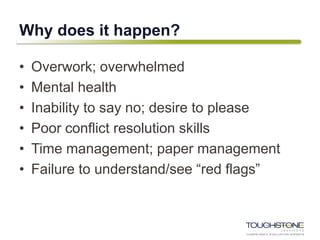

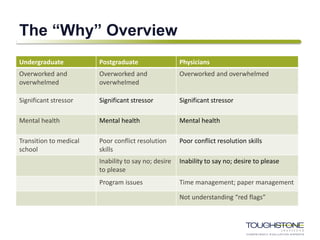

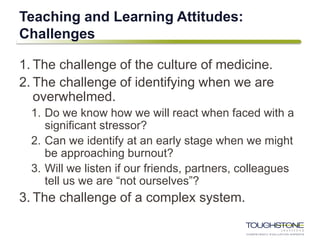

Erika Abner discussed her experience teaching professionalism to medical students, residents, and physicians through individualized instruction and coaching. She summarized common issues seen such as reliability, boundaries, and mental health. Factors contributing to lapses included stress, life events, workload, and inability to say no. Teaching strategies included direct instruction, role modeling, cases studies, and coaching skills like conflict resolution, self-care, and receiving feedback. Challenges included identifying one's limits and the medical culture. System-level responses are needed like promoting wellness and compassionate regulation. Focusing on "why" issues occur, finding balance, and supporting wellness programs can help address professionalism lapses.

![“Rather than searching for a system to find the “bad

apples,” should we view the problem from an

alternative standpoint, where any professional, when

challenged by life events, has the potential of losing

his or her way and putting patients and colleagues at

unnecessary risk?”

[Murphy, 2015 at 19]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erikaabner-190301142352/85/Perspectives-2019-Erika-Abner-5-320.jpg)

![Professionalism Frameworks

1. Virtues-based

– Able to apply ethical reasoning, restrain self-interest, and

demonstrate compassion and respect as a humane person.

2. Competency

– A domain of competence (behaviours) to be mastered,

demonstrated and assessed.

3. Identity formation

– Socialization into thinking, acting, and feeling like a professional.

[Irby, 2016 at 1606]

4. Social control

– Medicine’s promise to police itself in the public interest.

– Individual ability and willingness to self-regulate in the public

interest. [Hafferty, 2009 at 62]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erikaabner-190301142352/85/Perspectives-2019-Erika-Abner-7-320.jpg)

![Teaching and Learning [Irby, 2016 at 1609]

Strategies Virtue-based Behavior-based Professional identity

Pedagogy Direct instruction, role

models, case studies,

reflective writing, guided

discussion, appreciative

inquiry, white coat

ceremonies

Direct instruction, role

models, case studies,

coaching, simulations,

reflection on action

Direct instruction, role

models, case studies,

reflective writing, guided

discussion, appreciative

inquiry](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erikaabner-190301142352/85/Perspectives-2019-Erika-Abner-8-320.jpg)

![Shifting to thinking about the system….

“Burnout is primarily a system-level problem

driven by excess job demands and

inadequate resources and support, not an

individual problem triggered by personal

limitations.” [Shanafelt et al at 1828]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erikaabner-190301142352/85/Perspectives-2019-Erika-Abner-25-320.jpg)

![System-level Responses

Canadian Medical Protective

Association

1. Medical Schools should develop a

culture of wellness.

2. Medical organizations should look

for ways to assist physicians.

3. Medical regulators should aim for

“compassionate regulation.”

4. Institutional and hospital leaders

should recognize the business

case.

5. Governments should invest in

physician wellness. [CMPA 2018]

Federation of State Medical Boards

[US]

1. State medical boards should

emphasize the importance of

physician health, self-care, and

treatment-seeking….

2. Professional medical societies have

a key role in encouraging physicians

to seek treatment….

3. Centers for Medicaid and Medicare

services should carefully analyze

any new requirements placed on

physicians to determine their

potential impact on physician

wellness.

4. Medical schools and residency

programs should continue to

improve the culture of medicine.

[FSMB Workgroup 2018 Report,

selected recommendations]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erikaabner-190301142352/85/Perspectives-2019-Erika-Abner-26-320.jpg)