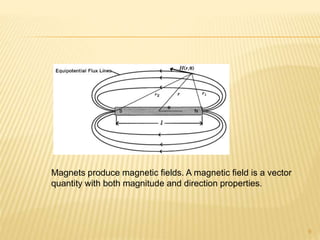

Magnetometers are instruments used to measure magnetic fields. There are two main types: vector magnetometers measure the direction and magnitude of magnetic fields, while scalar magnetometers measure only magnitude. Common vector magnetometer types include induction coil, fluxgate, and SQUID, while scalar types are proton precession and optically pumped. Magnetometers are used to study the Earth's magnetic field and detect magnetic anomalies. The Earth's field is generated by electric currents in the Earth's core and ionosphere. Magnetometer measurements provide information about these fields and currents.

![HOW MAGNETOMETERS WORK

Magnetometer measures the magnetic field it

is applied to. The magnetometer outputs

three magnitudes: X, Y and Z. From these

three values you can construct the magnetic

field vector (magnitude and direction)

B= [X, Y, Z]

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/persentationonmagnetometer-160909195841/85/Persentation-on-magnetometer-33-320.jpg)