Coral-shaped zinc oxide (ZnO) nanostructures were successfully synthesized via a combustion method using glycine as a fuel and zinc nitrate and lanthanum nitrate as precursors. Transmission electron microscopy showed the ZnO to have a coral shape with pore sizes of 10-50 nm and grain size of around 15 nm. X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed the hexagonal wurtzite crystal structure of both pure and lanthanum-doped ZnO. The lattice parameters increased with increasing lanthanum concentration, indicating incorporation of lanthanum ions into the ZnO lattice. Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy showed the band gap increased and absorbance decreased in the near UV region with higher lanthanum doping

![Optical studies of nano-structured La-doped ZnO prepared by

combustion method

L. Arun Jose a

, J. Mary Linet a

, V. Sivasubramanian b

, Akhilesh K. Arora c

, C. Justin Raj d

,

T. Maiyalagan e

, S. Jerome Das a,n

a

Department of Physics, Loyola College, Chennai 600034, India

b

Light Scattering Studies Section, IGCAR, Kalpakkam 603102, India

c

Condensed Matter Physics Division, IGCAR, Kalpakkam 603102, India

d

Pusan National University, Jangjeon, Geumjeong, Busan 609 735, South Korea

e

School of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639 798, Singapore

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 4 August 2011

Received in revised form

13 March 2012

Accepted 14 March 2012

Available online 21 April 2012

Keywords:

Doping

Semiconducting II–VI materials

Nano-structures

combustion

X-ray diffraction spectra

Zinc compounds

Rare earth compounds

a b s t r a c t

Coral-shaped nano-structured zinc oxide (ZnO) was successfully synthesized and La-

doped via a facile combustion process using glycine as a fuel. The auto-ignition

(at $185 1C) of viscous reactants zinc nitrate and glycine resulted in ZnO powders.

Hexagonal wurtzite structure of pure and doped ZnO powder was confirmed by X-ray

powder diffraction analysis. The transmission electron micrograph shows that the

nano-structured ZnO is coral-shaped and possess maximal pore ($10–50 nm pore size)

density in it and the grain size is approximately about 15 nm. Addition of dopants

subsequently alters the structural and optical properties which were confirmed by

UV–VIS studies.

& 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Nano-structured metal oxide semiconductors are gain-

ing attention due to their wide band-gap and related

properties [1]. Recent decades are witnessed with

researchers paying much interest in synthesis and char-

acterization of II–VI group semiconducting materials at

nano- [2] and bulk [3] levels. Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a widely

exploited, due to its excellent physical and chemical

properties. Numerous researchers proposed the solution

combustion method to synthesize simple and mixed

metal oxides [4–9]. Normally ZnO is doped with different

types of metallic ions in order to enhance the optical and

conducting properties [10–14]. The exceptional interest

on ZnO may be seen in the recent literatures. The

modified ZnO may be used as a base material for diluted

magnetic semiconductors [15–18], gas sensors [19],

photocatalysts [20], field-effect transistors [21,22], light-

emitting materials [23–25], solar cells [26,27] and biolo-

gical systems (drug delivery, bio-imaging, etc.) [28,29]. In

the recent times, rare earth metal-doped ZnO (e.g., Tb, Er,

Eu, Dy and Sm) has been broadly researched and concen-

trated on luminescence properties [24,30–33]. Lantha-

num (La)-doped ZnO nano-structures exhibit excellent

photocatalytic activity and gas sensitivity [20,34–36].

Nano-sized ZnO has been synthesized by the solution

combustion method and there are no literature references

for La-doped ZnO using this method. Current work is focused

on investigating the result of La doping concentration on the

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mssp

Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing

1369-8001/$ - see front matter & 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2012.03.011

n

Corresponding author. Tel.: þ91 44 2817 5662;

fax: þ91 44 2817 5566.

E-mail addresses: sjeromedas2004@yahoo.com,

jerome@loyolacollege.edu (S. Jerome Das).

Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 15 (2012) 308–313](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/opticalstudiesofnano-structuredla-dopedznopreparedbycombustionmethod-160428034631/75/Optical-studies-of-nano-structured-la-doped-zn-o-prepared-by-combustion-method-1-2048.jpg)

![microstructure and optical properties of ZnO nano-structure

prepared by the combustion method.

2. Experimental details

Distinct from usual thermal evaporation, ZnO nano-

structures were prepared by the combustion method, which

allows efficient synthesis of nano-size materials. This pro-

cess involves a self-sustained reaction in homogeneous

solution of different oxidizers (e.g., metal nitrates) and fuels

(e.g., urea, glycine, citric acid, hydrazides). Depending on the

type of precursors, and the suitable conditions for chemical

reaction to take place, zinc nitrate (Zn(NO3)2 Á 6H2O) was

chosen as an oxidizer and glycine (NH2CH2COOH) as a fuel,

since its combustion heat (À3.24 kcal/g) is more negative

when compared with urea (À2.98 kcal/g) or citric acid

(À2.76 kcal/g) [36]. Lanthanum nitrate (La(NO3)2 Á 6H2O) is

added to zinc nitrate with required molar ratio and glycine

is also added along with it, in a molar ratio of 0.9:1 (zinc

nitrateþlanthanum nitrate:glycine) and stirred well for 1 h

in 100 ml double distilled water. The obtained solution is

heated ($185 1C) till combustion reaction occurs. Proce-

dural flow chart diagram for the preparation of precursors

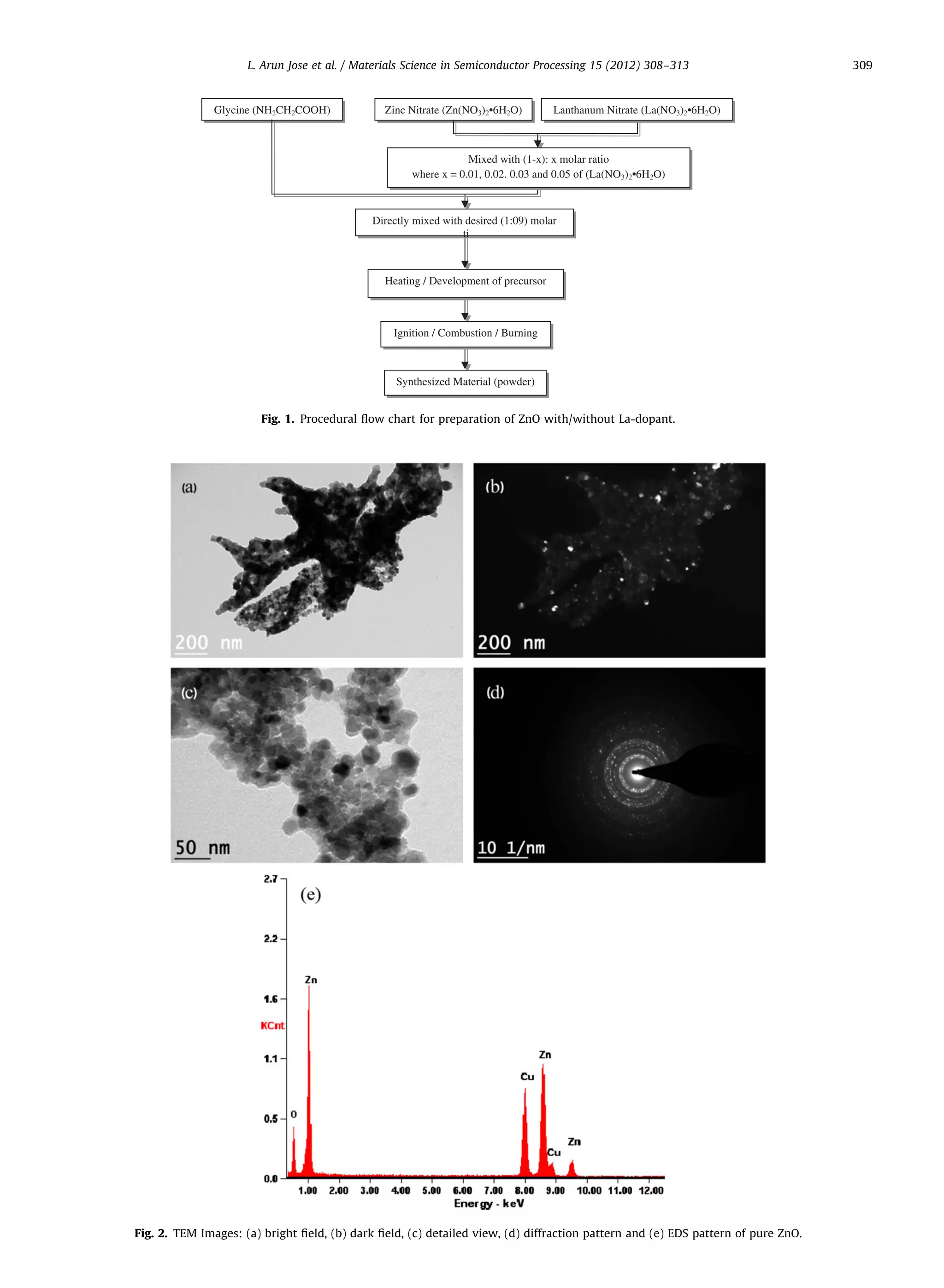

and the formation of nano-structures is shown in Fig. 1.

Crystallinity of pure ZnO and La-doped ZnO catalysts were

analyzed by Philips CM 20 Transmission Electron Micro-

scope which was operated between 20 and 200 kV. Com-

position of the samples were analyzed by energy dispersive

X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) attached to the TEM instrument.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the synthesized samples were

Fig. 3. TEM images: (a) bright field, (b) dark field, (c) detailed view, (d) diffraction pattern and (e) EDS pattern of 5 mol % La-doped ZnO.

L. Arun Jose et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 15 (2012) 308–313310](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/opticalstudiesofnano-structuredla-dopedznopreparedbycombustionmethod-160428034631/75/Optical-studies-of-nano-structured-la-doped-zn-o-prepared-by-combustion-method-3-2048.jpg)

![recorded using PAN analytical X-ray diffractometer with Cu

Ka (1.5405 ˚A) radiation in the scan range 2y between 301

and 701 with a scan speed of 21/min. UV–VIS spectra of pure

ZnO and La-doped ZnO catalysts were recorded using Varian

CARY 5E UV–VIS–NIR Spectrophotometer. The absorbance

spectra were then recorded in the range 200–700 nm.

Photoluminescence of pure ZnO and La-doped ZnO were

measured by Jobin Yvon Fluorolog spectrofluorometer and

the results are discussed in detail.

3. Results and discussion

TEM analysis shows that the nano-structures which

had been synthesized using combustion processing are

coral-shaped and porous as shown in Fig. 2. This shape

may be attributed to the thermal fluctuations while

synthesizing the samples. Grain size is found to be

$10–20 nm both in the case of pure and doped ZnO.

Porous nature of the nano-structures significantly increases

as the La-dopant concentration increases as shown in Fig. 3.

Each individual nano-structure is about 450–1000 nm

formed by tiny spherical ZnO nanoparticles. We can also

notice that the pores are $10–50 nm in diameter which

considerably increase the surface to volume ratio. Selected

area diffraction patterns match very well with wurtzite

ZnO in both pure and doped ZnO. EDS analysis shows that

some La3þ

ions have been incorporated into the ZnO lattice

by substituting zinc ions as shown in Fig. 3(e) and in

Table 1. When La is present the composition of oxygen

seems to be nearly constant. This may be due to the

addition of oxygen atoms in the La-doped ZnO which was

accommodated by the additional vacancy in the La3þ

ion.

Copper peak in the EDS measurement originates from the

TEM supporting carbon coated copper grid.

XRD profiles of synthesized pure and doped materials

in appropriate ratio are shown in Fig. 4. The diffraction

peaks and their relative intensities match with the JCPDS

card no. 36-1451. Hence the observed patterns can be

clearly endorsed to the presence of hexagonal wurzite

structure. XRD peak of lanthanum oxide was not observed

even for the La-doped sample with a high La concentra-

tion, suggesting that lanthanum oxide is uniformly dis-

persed in the ZnO and no second phase such as La2O3 and

La(OH)3 appears. It is evident that the introduction of La

ions does not alter the structure of ZnO and dopant

disperses homogeneously in the ZnO matrix as previously

reported [37]. Using the Scherrer equations the crystallite

sizes were estimated to be around 450 nm from the full-

width at half-maximum (FWHM) of diffraction peaks. The

diffraction pattern of ZnO is observed between the 2y

values of 301 and 701. The peak intensities of doped ZnO

increases with dopant concentration. Therefore, the crys-

talline nature of ZnO nanostructure increases with La-

dopant in the same manner as previously reported in the

case of Fe doped ZnO [38]. Doping of La ions restrains the

growth of ZnO grains and dopant with smaller ionic

radius has a constructive effect on diffusivity which

promotes orientation growth and good crystal [39]. The

lattice parameters and the unit cell volume were deter-

mined using software program UnitCell method of TJB

Holland & SAT Redfern [40]. The determined unit cell

parameters, volume and c/a were plotted as a function of

La concentrations and are shown in Figs. 5 and 6 respec-

tively. The lattice constant gradually increases with

increase in concentration of La3 þ

ions. Consequently, cell

volume and c/a ratio changed, agreeing with the fact that

ionic radii of La3 þ

is higher than the Zn2 þ

ion (0.106 nm

for La and 0.074 nm for Zn) [41,42] but there is a small

variation in c-axis compared with the results of Chen et al.

[37]. This distortion in the lattice parameters confirms the

incorporation of La3 þ

ions up to 5 mol% in ZnO wurzite

structure.

UV–VIS spectrum shows that the absorbance is high

below 380 nm for pure ZnO and as the La-dopant con-

centration increases the absorbance of ZnO decreases

considerably below this region as shown in Fig. 7. The

corresponding band gap values of pure and doped ZnO are

Table 1

Composition of elements in La-doped ZnO samples.

La concentration (mol%) Element weight (%) Atomic (%)

0 O 13.30 38.50

Zn 86.70 61.50

1 O 20.30 51.73

La 04.34 01.27

Zn 75.36 47.00

2 O 19.60 51.32

La 08.38 02.53

Zn 72.02 46.15

3 O 18.94 50.92

La 12.15 03.76

Zn 68.91 45.32

5 O 18.30 50.80

La 17.20 05.50

Zn 64.50 43.70

Fig. 4. Powder XRD spectra of samples pure–doped prepared at different

mol percent of La.

L. Arun Jose et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 15 (2012) 308–313 311](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/opticalstudiesofnano-structuredla-dopedznopreparedbycombustionmethod-160428034631/75/Optical-studies-of-nano-structured-la-doped-zn-o-prepared-by-combustion-method-4-2048.jpg)

![presented in Fig. 8. It can be clearly seen that the band gap

of La-doped ZnO also increases gradually with increase in

La concentration. After 380 nm, absorbance of pure ZnO is

less compared with La-doped ZnO and absorbance

increases with increase in dopant concentration.

Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of La-doped ZnO

nano-structures were measured with an excitation wave-

length of 285 nm and is shown in Fig. 9. The intensity of

PL emission is found to increase with increase in La-

dopant, but the intensity of doped ZnO decreases in

comparison with pure ZnO between 3.2 and 3.3 eV. The

PL spectrum shows the La characteristic emission band at

$2.9 eV and near UV emission between 3.27 and 3.30 eV.

There is a shift in the emission spectra for pure and doped

ZnO. This may be attributed due to the strain created in

the crystal lattice to accommodate larger La atoms.

Spectra in the range of 340–460 nm (2.7–3.6 eV) shows

that a violet peak at about 420 nm (2.95 eV) and the

intensity of emission are found to be strongly reliant on

the La concentration. Traps on the grain surface per unit

volume increases with the increase of specific surface

area. Cordaro et al. [43] assumed that interface traps lie in

Fig. 7. UV–VIS spectra ZnO with/without dopant.

Fig. 8. Calculated band gap of pure and La-doped ZnO.

Fig. 5. Unit cell parameters a and c were plotted as a function of La

concentration.

Fig. 6. Unit cell volume and c/a were plotted as a function of La

concentration.

Fig. 9. Room temperature PL emission spectra of ZnO with/without

La-dopant.

L. Arun Jose et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 15 (2012) 308–313312](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/opticalstudiesofnano-structuredla-dopedznopreparedbycombustionmethod-160428034631/75/Optical-studies-of-nano-structured-la-doped-zn-o-prepared-by-combustion-method-5-2048.jpg)

![the depletion regions and locate at the ZnO–ZnO grain

boundaries when a polycrystalline varistor forms, and the

level of interface trap was found to be about 0.33 eV

below the conduction band edge. So violet emission is

possibly attributed to the recombination centers linked

with interface traps existing at the grain boundaries, and

radiative transition occurs between the level of interface

traps and the valence band.

4. Conclusions

La-doped ZnO was prepared by combustion proces-

sing; doping levels included undoped, 1, 2, 3 and 5 molar

percentage. Significant transformation was observed upon

different doping concentrations. Transmission electron

micrograph shows an enhancement of pore density for

doped ZnO. Lattice parameters and unit cell volume were

determined from the XRD data and it confirms the entry

of La-dopant inside ZnO crystal lattice by the increase in

lattice constants. It is evident that the absorbance near UV

region decreases with increase in dopant concentration.

The bandgap is found to increase with addition of La. The

La-doped ZnO nano-structures prepared at low tempera-

tures are more suitable for applications such as chemical

and biological sensors, optoelectronic devices, and

solar cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge BRNS (Board of

Research in Nuclear Sciences—Government of India, Pro-

ject no. 2008/37/12/BRNS/1513) for providing financial

assistance. They are also thankful to authorities of Indian

Institute of Technology, Chennai 36, for providing TEM,

UV–VIS, PL and powder XRD facility.

References

[1] J.B. Varley, A. Janotti, C. Franchini, C.G. Van de Walle, Physical

Review B 85 (2012) 081109. R.

[2] P.K. Sharma, R.K. Dutta, M. Kumar, P.K. Singh, A.C. Pandey, Journal

of Luminescence 129 (2009) 605–610.

[3] J. Kennedy, D.A. Carder, A. Markwitz, R.J. Reeves, Journal of Applied

Physics 107 (2010) 103518.

[4] H.-C. Shin, K.-R. Lee, S. Park, C.-H. Jung, S.-J. Kim, Japanese Journal of

Applied Physics 35 (1996) L996–L998.

[5] F. Li, K. Hu, J. Li, D. Zhang, G. Chen, Journal of Nuclear Materials 300

(2002) 82–88.

[6] L.E. Shea, J. McKittrick, O.A. Lopez, E. Sluzky, Journal of the

American Ceramic Society 79 (1996) 3257–3265.

[7] L. Chick, L. Pederson, G. Maupin, J. Bates, L. Thomas, G. Exarhos,

Materials Letters 10 (1990) 6–12.

[8] T. Mimani, K.C. Patil, Materials Physics and Mechanics 4 (2001)

134–137.

[9] R.D. Purohit, B.P. Sharma, K.T. Pillai, A.K. Tyagi, Materials Research

Bulletin 36 (2001) 2711–2721.

[10] B.D. Ahn, S.H. Oh, C.H. Lee, G.H. Kim, H.J. Kim, S.Y. Lee, Journal of

Crystal Growth 309 (2007) 128–133.

[11] H. Huang, Y. Ou, S. Xu, G. Fang, M. Li, X. Zhao, Applied Surface

Science 254 (2008) 2013–2016.

[12] V. Zhitomirsky, E. Cetinorgu, R. Boxman, S. Goldsmith, Thin Solid

Films 516 (2008) 5079–5086.

[13] T. Moriga, Y. Hayashi, K. Kondo, Y. Nishimura, K.-i. Murai,

I. Nakabayashi, H. Fukumoto, K. Tominaga, Journal of Vacuum

Science and Technology A 22 (2004) 1705.

[14] S. Saha, V. Gupta, AIP Advances 1 (2011) 042112.

[15] T.S. Herng, S.P. Lau, S.F. Yu, H.Y. Yang, K.S. Teng, J.S. Chen, Journal of

Physics: Condensed Matter 19 (2007) 356214.

[16] N.H. Hong, J. Sakai, V. Brize´, Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter

19 (2007) 036219.

[17] J. Zhang, X.Z. Li, J. Shi, Y.F. Lu, D.J. Sellmyer, Journal of Physics:

Condensed Matter 19 (2007) 036210.

[18] B. Li, X. Xiu, R. Zhang, Z. Tao, L. Chen, Z. Xie, Y. Zheng, Materials

Science in Semiconductor Processing 9 (2006) 141–145.

[19] T. Gao, T.H. Wang, Applied Physics A 80 (2004) 1451–1454.

[20] S. Anandan, A. Vinu, T. Mori, N. Gokulakrishnan, P. Srinivasu, V.

Murugesan, K. Ariga, Catalysis Communications 8 (2007)

1377–1382.

[21] Z.-X. Xu, V.A.L. Roy, P. Stallinga, M. Muccini, S. Toffanin, H.-F. Xiang,

C.-M. Che, Applied Physics Letters 90 (2007) 223509.

[22] C.-L. Hsu, T.-Y. Tsai, Journal of the Electrochemical Society 158

(2011) K20–K23.

[23] Y.R. Ryu, J.A. Lubguban, T.S. Lee, H.W. White, T.S. Jeong, C.J. Youn,

B.J. Kim, Applied Physics Letters 90 (2007) 131115.

[24] X.M. Teng, H.T. Fan, S.S. Pan, C. Ye, G.H. Li, Journal of Applied

Physics 100 (2006) 053507.

[25] S. Chirakkara, S.B. Krupanidhi, Physica Status Solidi RRL 6 (2012)

34–36.

[26] X. Chen, B. Xu, J. Xue, Y. Zhao, C. Wei, J. Sun, Y. Wang, X. Zhang,

X. Geng, Thin Solid Films 515 (2007) 3753–3759.

[27] P. Ruankham, T. Sagawa, H. Sakaguchi, S. Yoshikawa, Journal of

Materials Chemistry 21 (2011) 9710–9715.

[28] S. Mendoza-Galva´n, C. Trejo-Cruz, J. Lee, D. Bhattacharyya,

J. Metson, P.J. Evans, U. Pal, Journal of Applied Physics 99 (2006)

014306.

[29] I. Honma, S. Hirakawa, K. Yamada, J.M. Bae, Solid State Ionics 118

(1999) 29–36.

[30] M. Peres, A. Cruz, S. Pereira, M.R. Correia, M.J. Soares, A. Neves,

M.C. Carmo, T. Monteiro, A.S. Pereira, M.A. Martins, T. Trindade,

E. Alves, S.S. Nobre, R.A.Sa´ Ferreira, Applied Physics A 88 (2007)

129–133.

[31] S. Bachir, K. Azuma, J. Kossanyi, P. Valat, J.C. Ronfard-Haret, Journal

of Luminescence 75 (1997) 35–49.

[32] X.T. Zhang, Y.C. Liu, J.G. Ma, Y.M. Lu, D.Z. Shen, W. Xu, G.Z. Zhong,

X.W. Fan, Thin Solid Films 413 (2002) 257–261.

[33] G. Wu, Y. Zhuang, Z. Lin, X. Yuan, T. Xie, L. Zhang, Physica E

31 (2006) 5–8.

[34] S. Anandan, A. Vinu, K.L.P. Sheeja Lovely, N. Gokulakrishnan,

P. Srinivasu, T. Mori, V. Murugesan, V. Sivamurugan, K. Ariga,

Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 266 (2007) 149–157.

[35] C. Ge, C. Xie, M. Hu, Y. Gui, Z. Bai, D. Zeng, Materials Science and

Engineering: B 141 (2007) 43–48.

[36] C.-C. Hwang, T.-Y. Wu, Journal of Materials Science 39 (2004)

6111–6115.

[37] J.T. Chen, J. Wang, F. Zhang, G.A. Zhang, Z.G. Wu, P.X. Yan, Journal of

Crystal Growth 310 (2008) 2627–2632.

[38] G.-Y. Ahn, S.-I. Park, S.-J. Kim, C.-S. Kim, Journal of Magnetism and

Magnetic Materials 304 (2006) e498–e500.

[39] S. Fujihara, C. Sasaki, T. Kimura, Journal of the European Ceramic

Society 21 (2001) 2109–2112.

[40] T.J.B. Holland, S.A.T. Redfern, Journal of Applied Crystallography 30

(1997) 84.

[41] S.H. Jeong, B.N. Park, S.B. Lee, J.H. Boo, Surface and Coatings

Technology 193 (2005) 340–344.

[42] Q. Yu, W. Fu, C. Yu, H. Yang, R. Wei, Y. Sui, S. Liu, Z. Liu, M. Li,

G. Wang, C. Shao, Y. Liu, G. Zou, Journal of Physics D: Applied

Physics 40 (2007) 5592.

[43] J.F. Cordaro, Y. Shim, J.E. May, Journal of Applied Physics 60 (1986)

4186.

L. Arun Jose et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 15 (2012) 308–313 313](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/opticalstudiesofnano-structuredla-dopedznopreparedbycombustionmethod-160428034631/75/Optical-studies-of-nano-structured-la-doped-zn-o-prepared-by-combustion-method-6-2048.jpg)