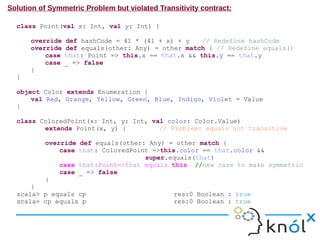

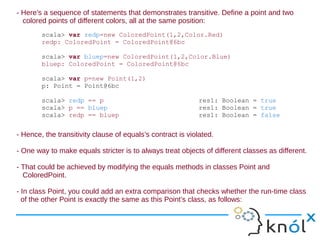

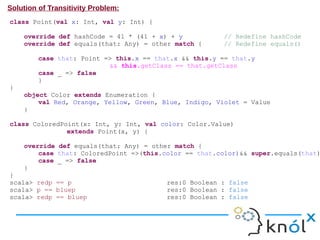

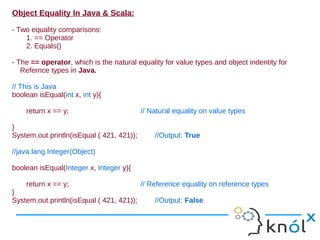

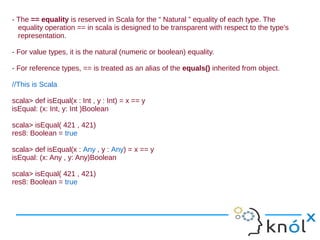

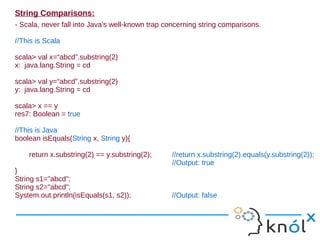

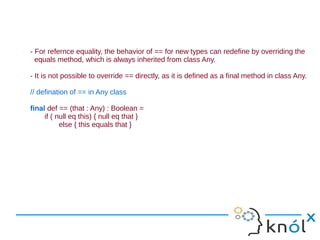

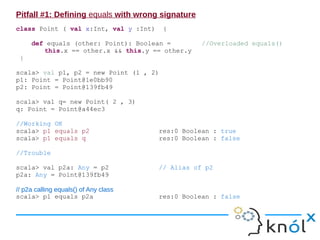

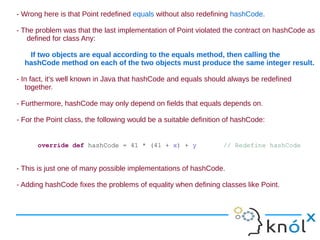

The document discusses object equality in Scala and Java, highlighting the differences in how equality is compared using the `==` operator and the `equals()` method. It identifies common pitfalls when overriding equality methods, such as improper signatures and the importance of consistency with the `hashcode` method. It concludes by emphasizing the significance of defining equality correctly to maintain the principles of reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity.

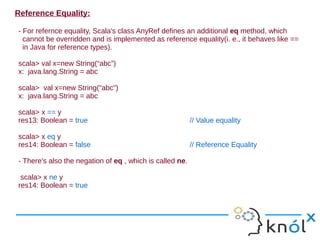

![Pitfall #2: Changing equals without also changing hashCode

//Previously defined equals method

class Point ( val x:Int, val y :Int) {

// A better definition:Overriding equals of Any class

override def equals(other: Any) = other match {

case that: Point => this.x == that.x && this.y == that.y

case _ => false

}

}

scala> import scala.collection.mutable._

import scala.collection.mutable._

scala> val p1, p2 = new Point (1 , 2)

p1: Point = Point@1bef480

p2: Point = Point@1a6068c

//storing p1 to collection

scala> val coll = HashSet (p1)

coll: scala.collection.mutable.Set[Point] = Set(Point@62d74e)

scala> coll contains p2 res2: Boolean = false](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/objectequalityinscala-121106060736-phpapp02/85/Object-Equality-in-Scala-11-320.jpg)

![Pitfall #3: Defining equals in terms of mutable fields:

- Consider the following slight variation of class Point:

class Point2(var x: Int, var y: Int) {

override def hashCode = 41 * (41 + x) + y // Redefine hashCode

override def equals(other: Any) = other match { // Redefine equals()

case that: Point2 => this.x == that.x && this.y == that.y

case _ => false

}

}

scala> val p = new Point(1, 2) p: Point = Point@2b

scala> val coll = HashSet(p)

coll: scala.collection.mutable.Set[Point] = Set(Point@2b)

scala> coll contains p res5: Boolean = true

scala> p.x += 1 // Changing p.x value

scala> coll contains p res7: Boolean = false

scala> coll.elements contains p res7: Boolean = true](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/objectequalityinscala-121106060736-phpapp02/85/Object-Equality-in-Scala-15-320.jpg)