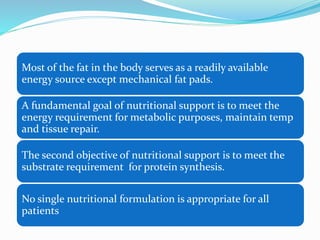

This document discusses nutrition and metabolism in injured or stressed patients. It covers several topics:

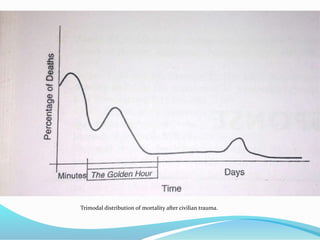

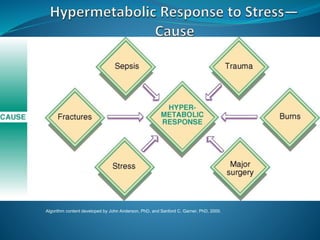

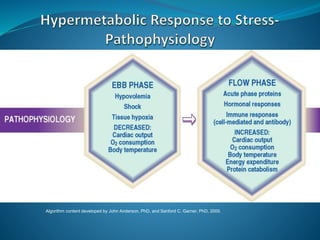

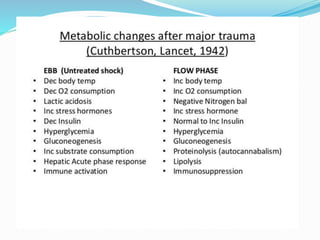

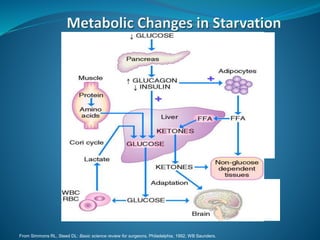

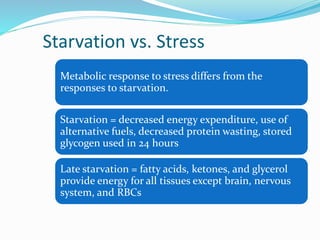

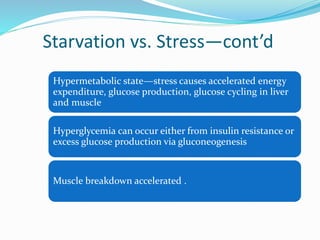

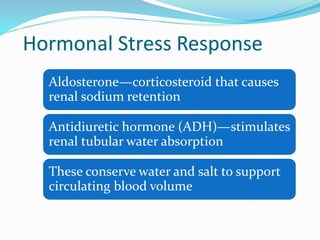

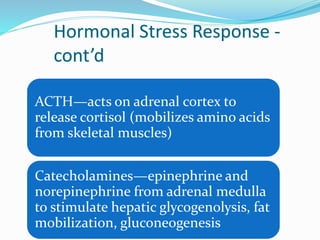

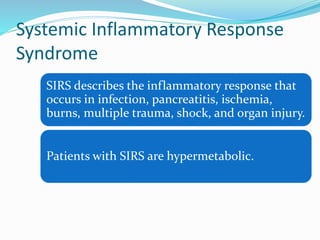

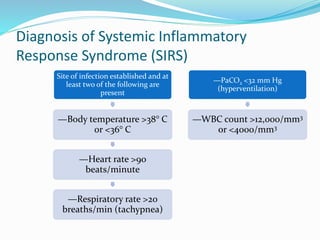

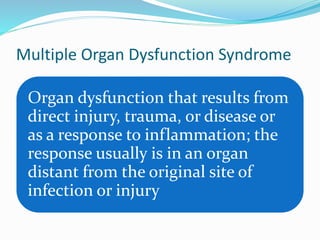

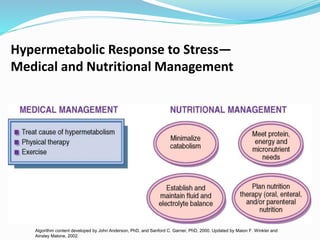

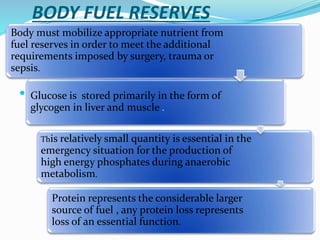

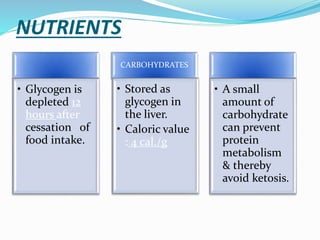

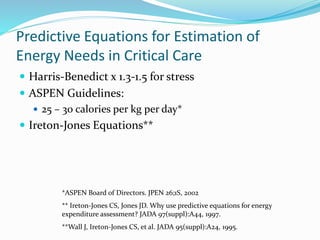

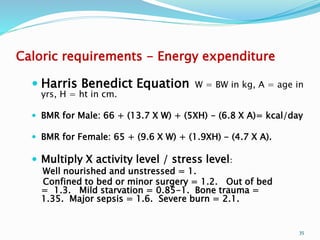

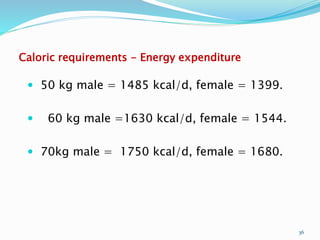

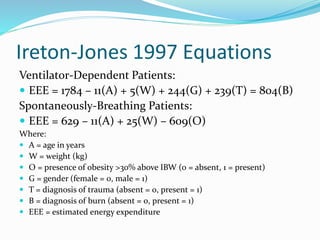

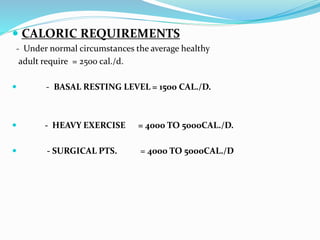

1. Injury causes an increase in energy requirements and metabolism. Insulin resistance occurs after injury.

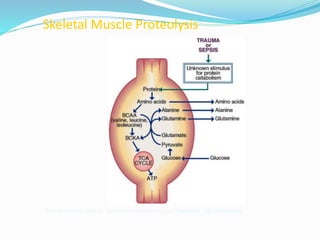

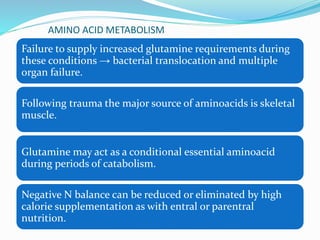

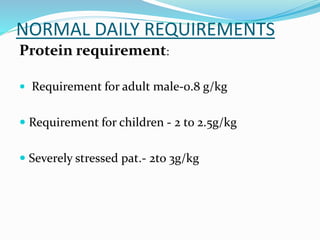

2. Protein from skeletal muscle breakdown is an important fuel source. Amino acids like glutamine are conditionally essential.

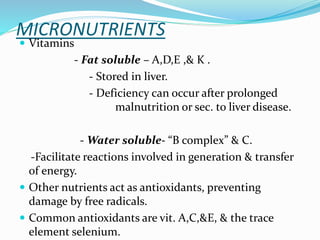

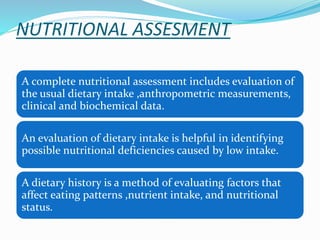

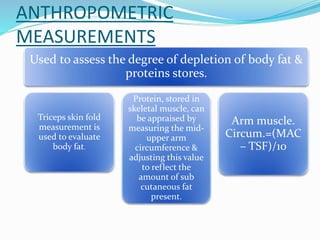

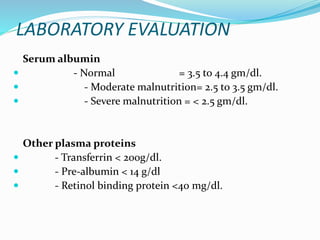

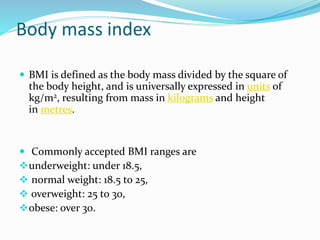

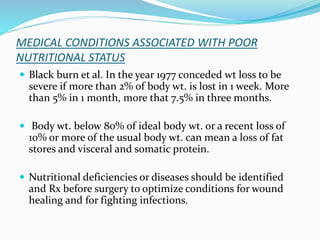

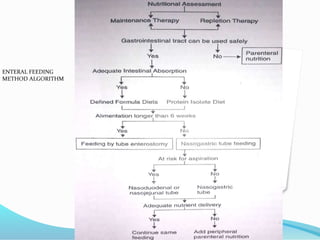

3. Nutritional assessments evaluate dietary intake, anthropometrics, and biomarkers to identify deficiencies.

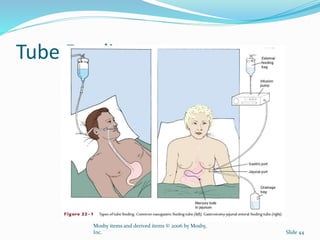

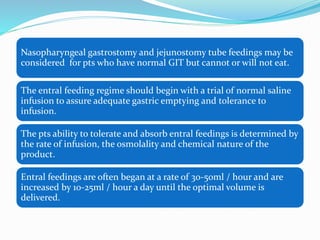

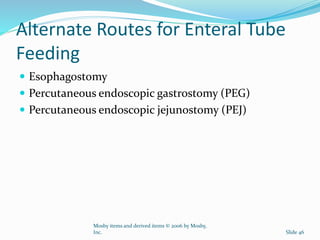

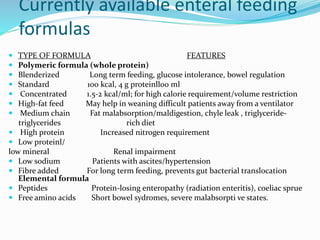

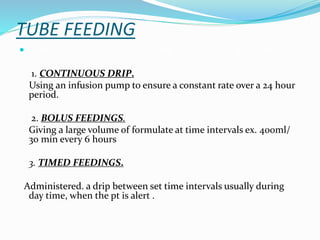

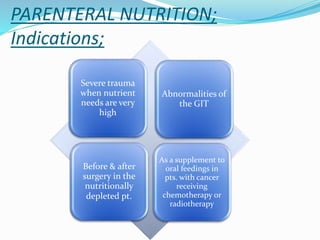

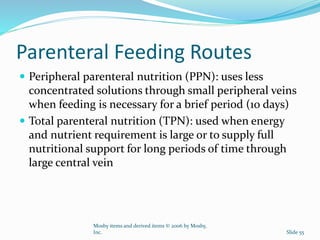

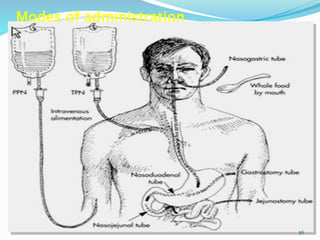

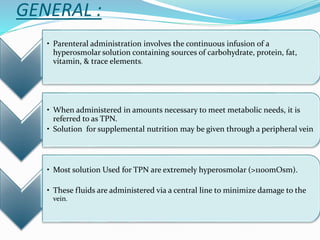

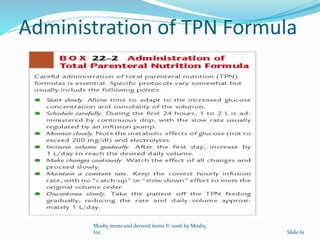

4. Various feeding methods can be used to meet increased caloric and protein needs in stressed patients. Maintaining proper nutrition supports healing and recovery from injury or illness.