The document discusses establishing Medical Computer Emergency Response Teams (MedCERT) to coordinate responses to cybersecurity incidents affecting medical devices and networks. It argues that healthcare cybersecurity is currently unprepared for emergencies and that response and recovery need to be emphasized in addition to prevention and protection. The document recommends that MedCERT teams receive training in the National Incident Management System and Incident Command System to effectively respond to incidents. It also calls for improved information sharing across the healthcare industry regarding cyber threats.

![1

Medical Computer Emergency Response Teams (MedCERT) and

Risks to Networked Medical Devices and Connected IT Networks

June 2017

Co-authors:

Kristina Freas, M.Sci., RN, EMT-P, CEM

And

Dave Sweigert, M.Sci., CEH, CISA, CISSP, EMT-B, HCISPP, PCIP, PMP, SEC+

ABSTRACT

The concept of a Medical Computer Emergency Response Team has been

proposed by the Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force. This research

paper provides a contextual backdrop to reduce the delay in implementing such

teams. Note: this document is considered scholarly research and distributed for

discussion purposes only.

Hospital emergency operations

Many hospital Emergency Managers will

appreciate this observation: ironically,

volunteer amateur radio operators that

support the auxiliary communications

component of a hospital’s Emergency

Operations Plans (EOP) have more

training in Emergency Management than

an entire hospital cyber security

department. Translation: radio operators

have received the appropriate

standardized training -- as required for

various levels of first responders.

Result: healthcare sector cybersecurity

may be unprepared to interface with

Emergency Management (E/M) during a

sector-wide cyber-attack.

Such potential catastrophic attacks are

no longer a presumed low probability.

Moderate probability may be more

accurate. Healthcare cybersecurity

incident response – within the E/M

context – may be disjointed from overall

response and needs improvement.

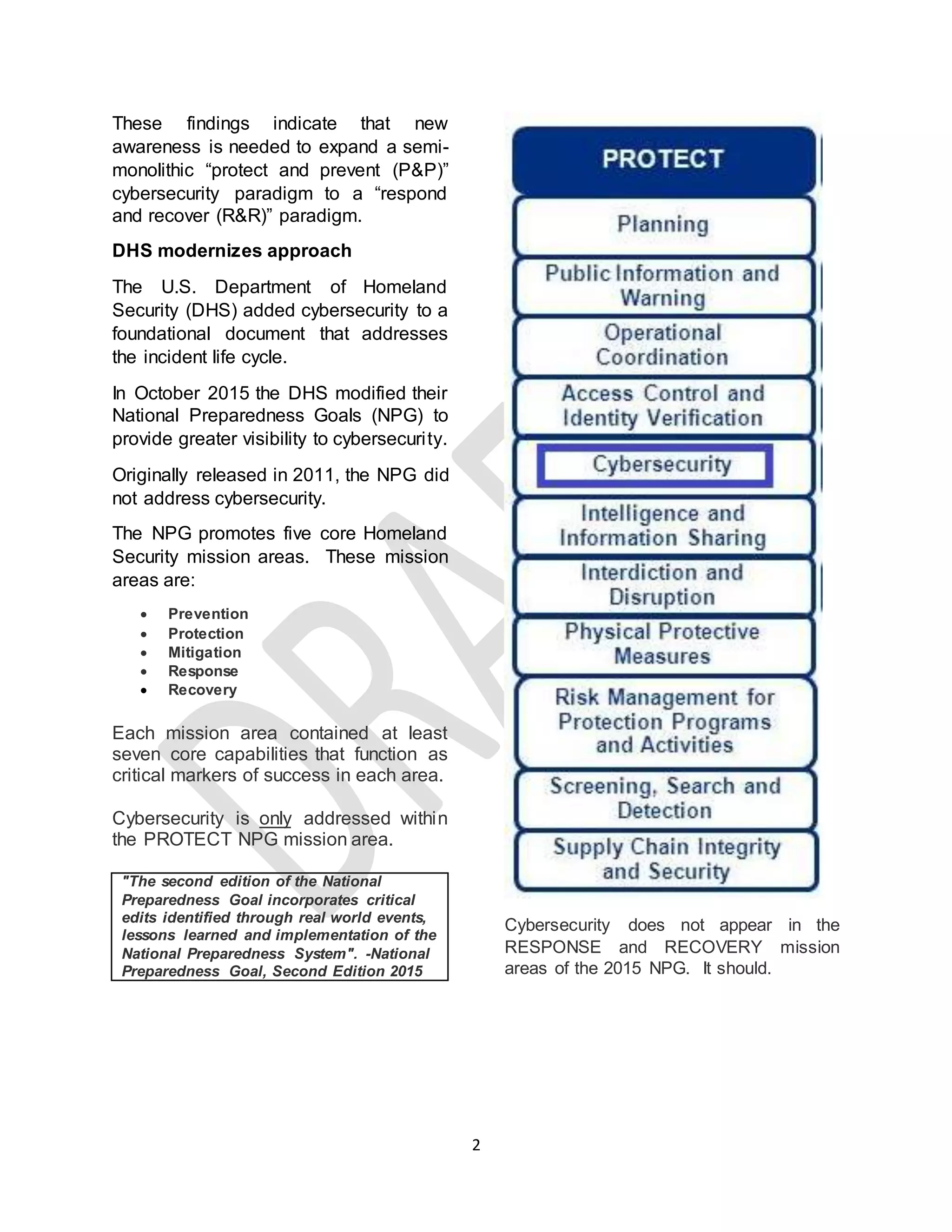

Cyber Task Force calls for MedCERT

The Health Care Industry Cybersecurity

Task Force, commissioned by the federal

Computer Information Sharing Act

(CISA), released a recommendation

report (6/2/17) with a special section

devoted to “Risks to Networked Medical

Devices and Connected IT Networks”.

Imperative recommendations included:

Establish a Medical Computer

Emergency Readiness Team (MedCERT)

to coordinate medical device-specific

responses to cybersecurity incidents and

vulnerability disclosures (2.6).

Broaden the scope and depth of

information sharing across the health

care industry and create more effective

mechanisms for disseminating and

utilizing data (6.2).

Encourage annual readiness exercises

by the health care industry (6.3).

See: Report on Improving Cybersecurity

in the Health Care Industry, 6/2/17, U.S.

Department of Health and Human

Services [DHHS].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/implement-med-cert-healthcare-cybersecurity-task-force-2-170607031705/75/Nursing-meets-Hacking-Medical-Computer-Emergency-Response-Teams-MedCERT-1-2048.jpg)

![4

Readiness exercises

Attention should be given to pre-incident

planning. Untested incident response

plans should be tested with walk-troughs,

dry-runs, testing, etc.

The end-game is to identify what types of

information are needed by various

decision makers to form an accurate

common operation picture – sometimes

called situational awareness.

Situational awareness is dependent on

appropriate communications pathways.

These critical communication pathways

and protocols need to be established and

tested prior to an incident providing a

coordinated and streamlined approach to

gathering information.

These pathways are typically identified in

workshops, trainings and table top

exercises (TTX) that develop and test

incident response plans.

Emergency Mangers should invite

counterparts in cybersecurity to attend

such events. Understanding what types

of information each party needs to help

the decision-making process is the goal

of these activities.

These activities help the healthcare

organization meet its obligations under

various compliance frameworks (The

Joint Commission [TJC] and Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]).

There are many opportunities for

healthcare organizations to participate in

Cyber TTX events sponsored by DHS.

These TTX events are conducted

nationwide 2-3 times a year.

Summary

Healthcare organizations that aspire to

implement some of the Task Force

recommendations should begin to

ensure a common baseline of knowledge

and understanding to the NIMS/ICS

framework. This should be a requirement

articulated in the EOP.

The entire healthcare sector should

adopt a forward learning position and

expect a sector-wide cyber-attack, with a

moderate probability that it may be

directed at the most vulnerable medical

devices that offer the cyber adversary an

opportunity to pivot deeper into the

connected network.

The sector should broaden the scope

and depth of information sharing across

the health care industry and create more

effective mechanisms for disseminating

and utilizing data.

Formalizing information gathering and

sharing is a planning consideration which

should not be overlooked.

About the co-authors:

Kristina Freas, M.Sci., RN, EMT-P,

CEM, is an experienced emergency

management professional and Certified

Emergency Manager (CEM) specializing in

the public health and healthcare critical

infrastructure sector.

Dave Sweigert, M.Sci., EMT-B, is a

Certified Ethical Hacker and holds

advanced emergency management

practitioner status conferred by FEMA

and CalOES. His passion is to enable

cybersecurity practitioners. Author of

Field Operations Guide to Ethical

Hacking.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/implement-med-cert-healthcare-cybersecurity-task-force-2-170607031705/75/Nursing-meets-Hacking-Medical-Computer-Emergency-Response-Teams-MedCERT-4-2048.jpg)