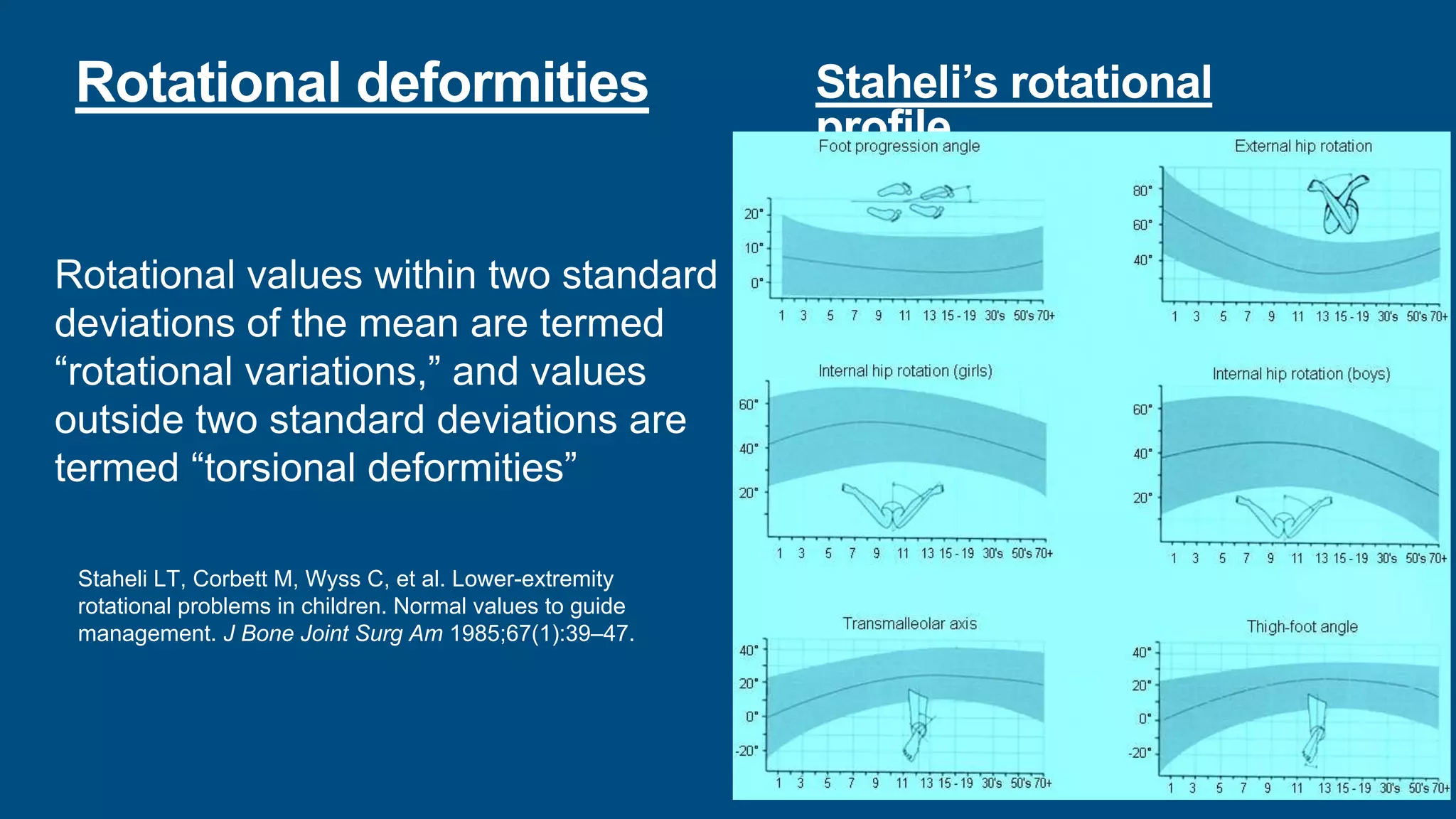

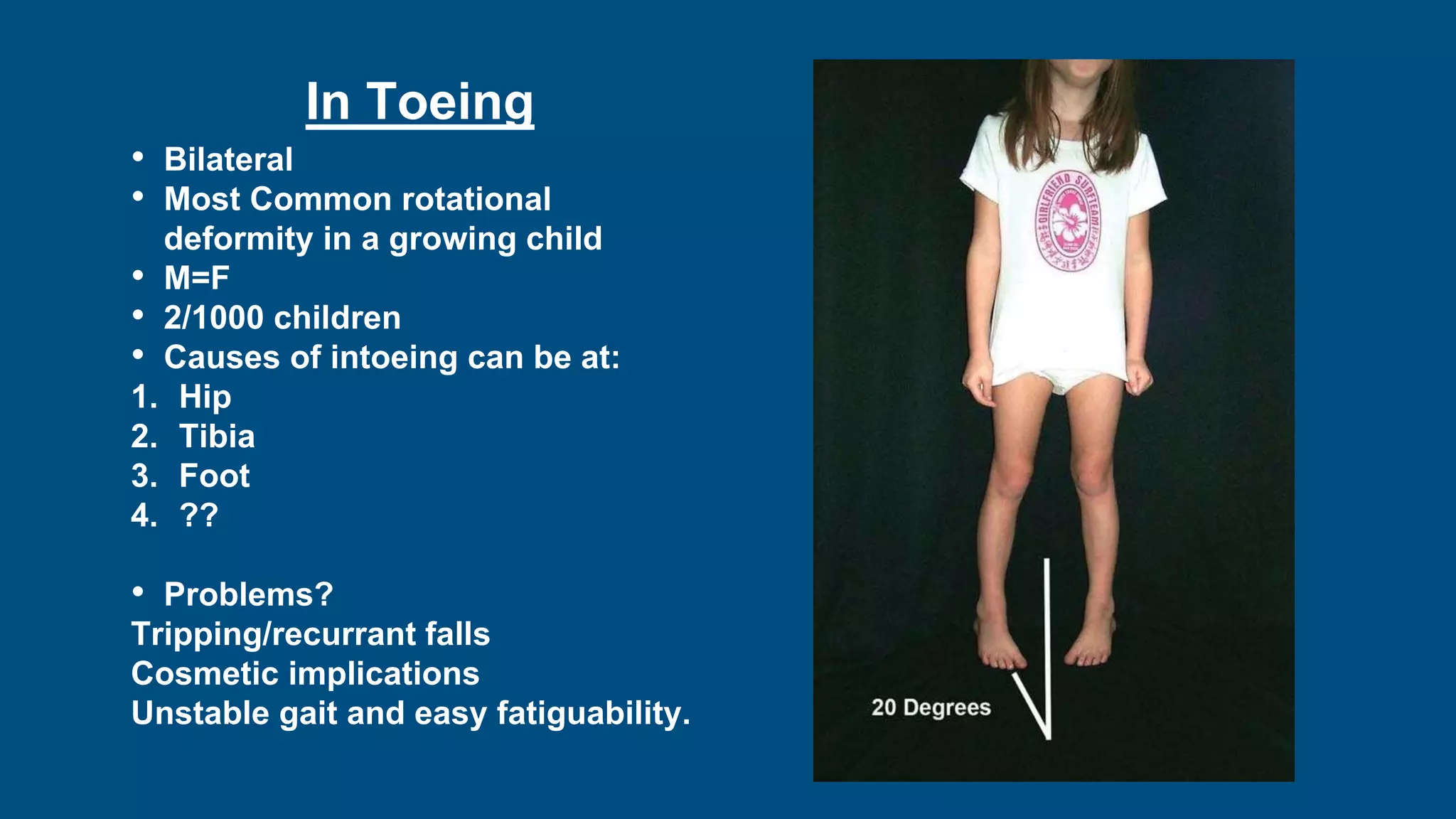

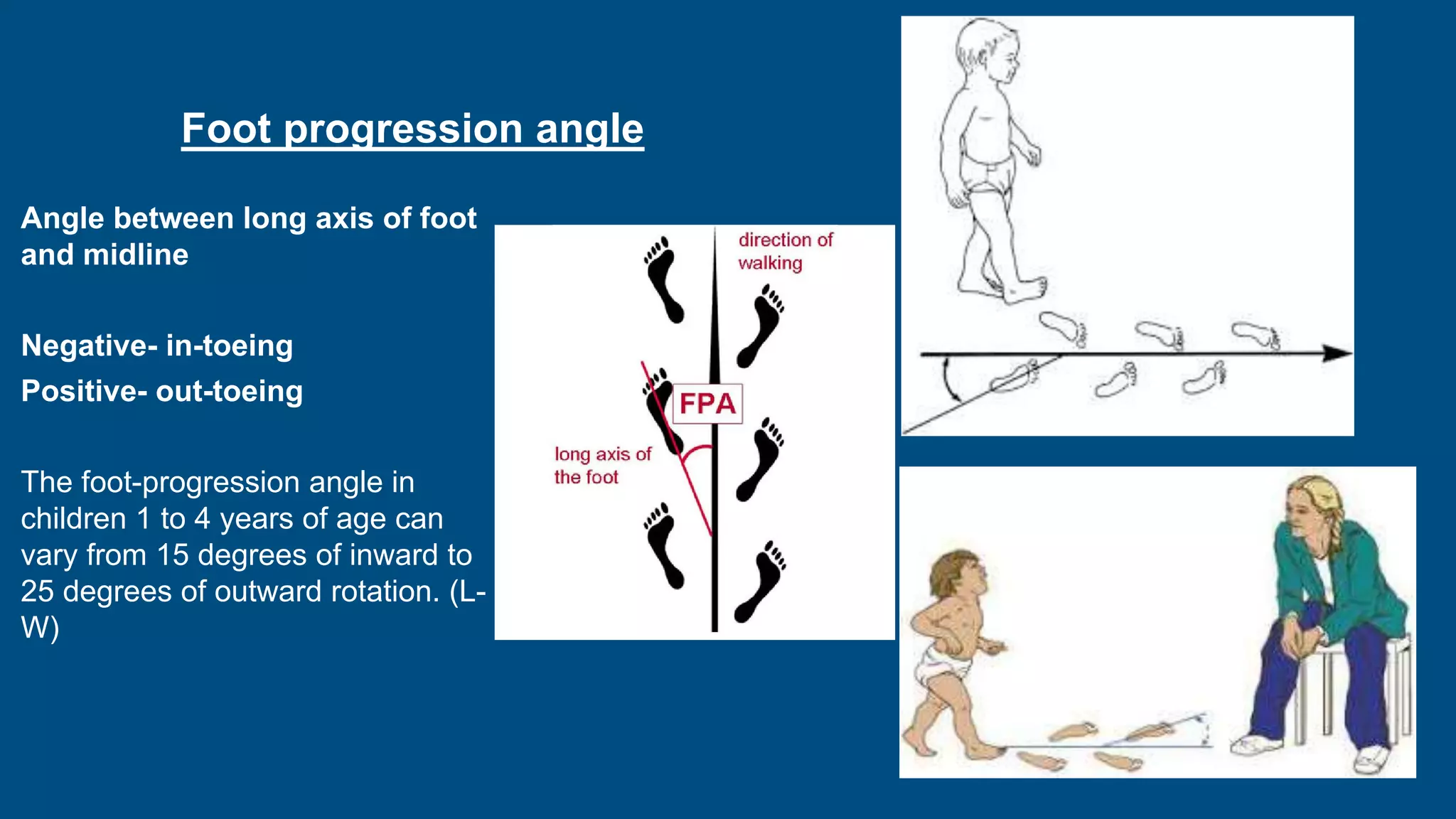

- Physiological variations in children such as intoeing, out-toeing, bowing of the legs, and flat feet are common and usually resolve on their own without intervention. Conditions that suggest an abnormality include asymmetry, limitation of movement, or progressive deformity.

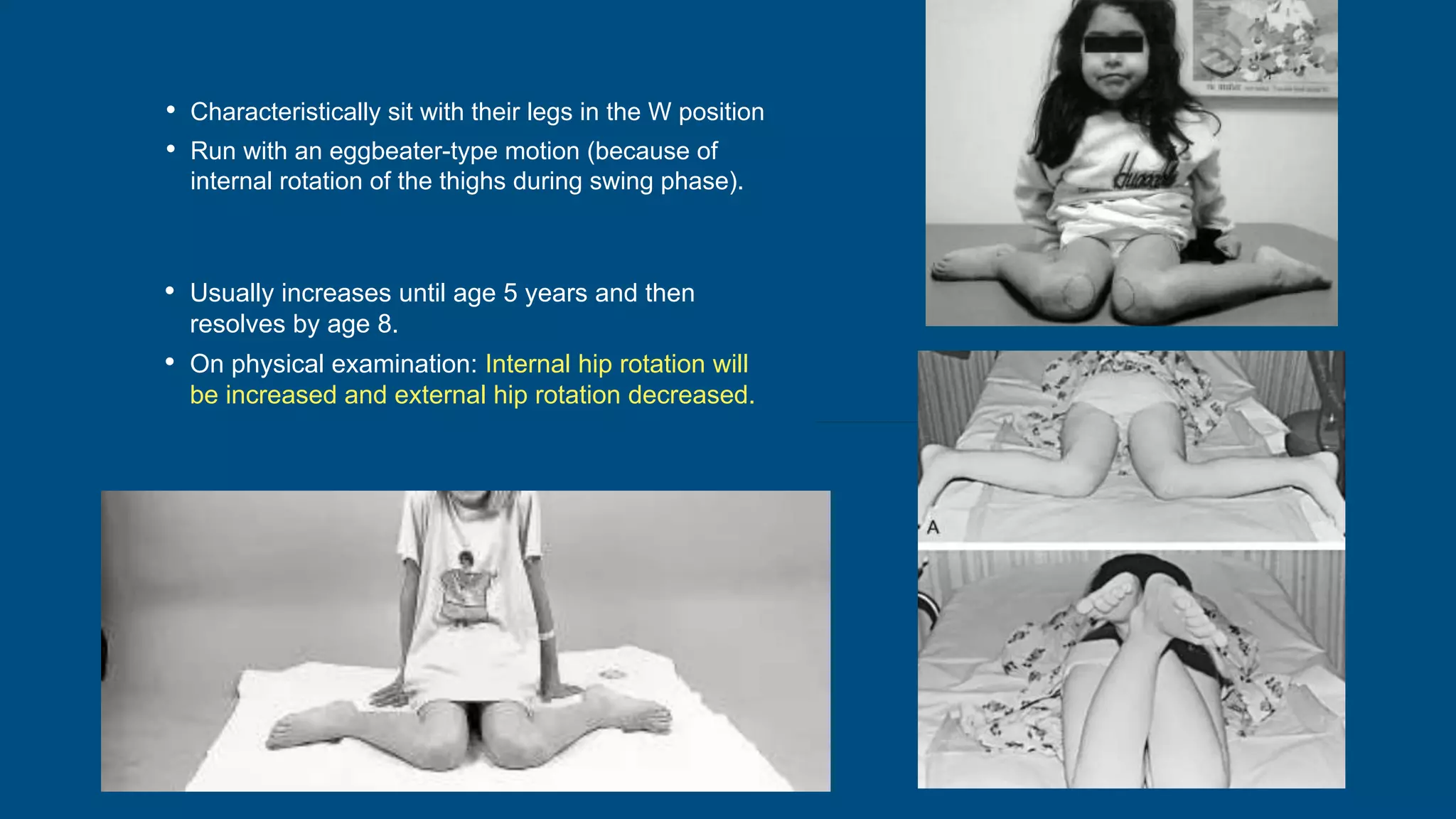

- Intoeing is most commonly caused by femoral anteversion or tibial torsion in young children and resolves by age 8 in 95% of cases. Out-toeing can be due to femoral retroversion or external tibial torsion.

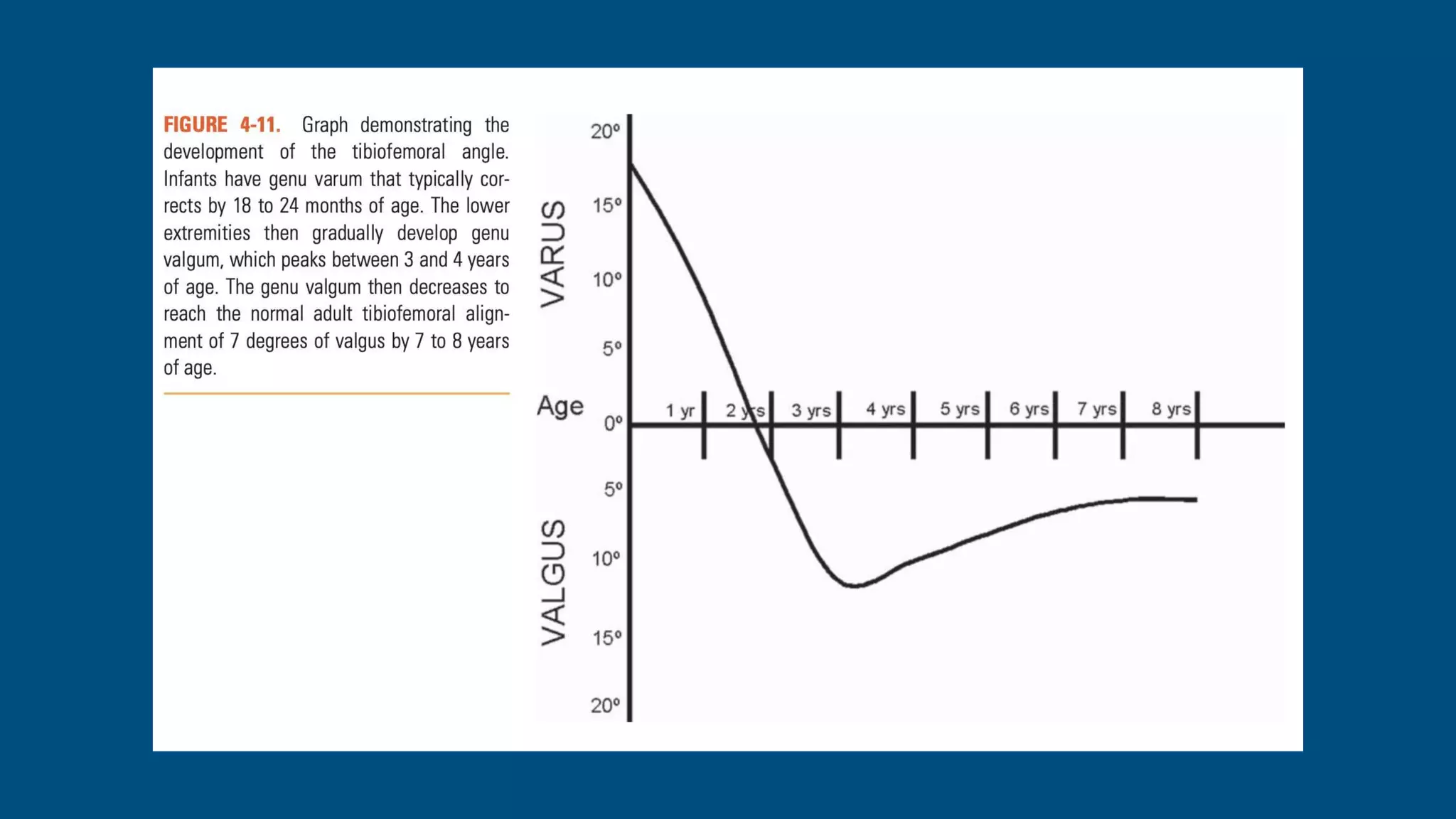

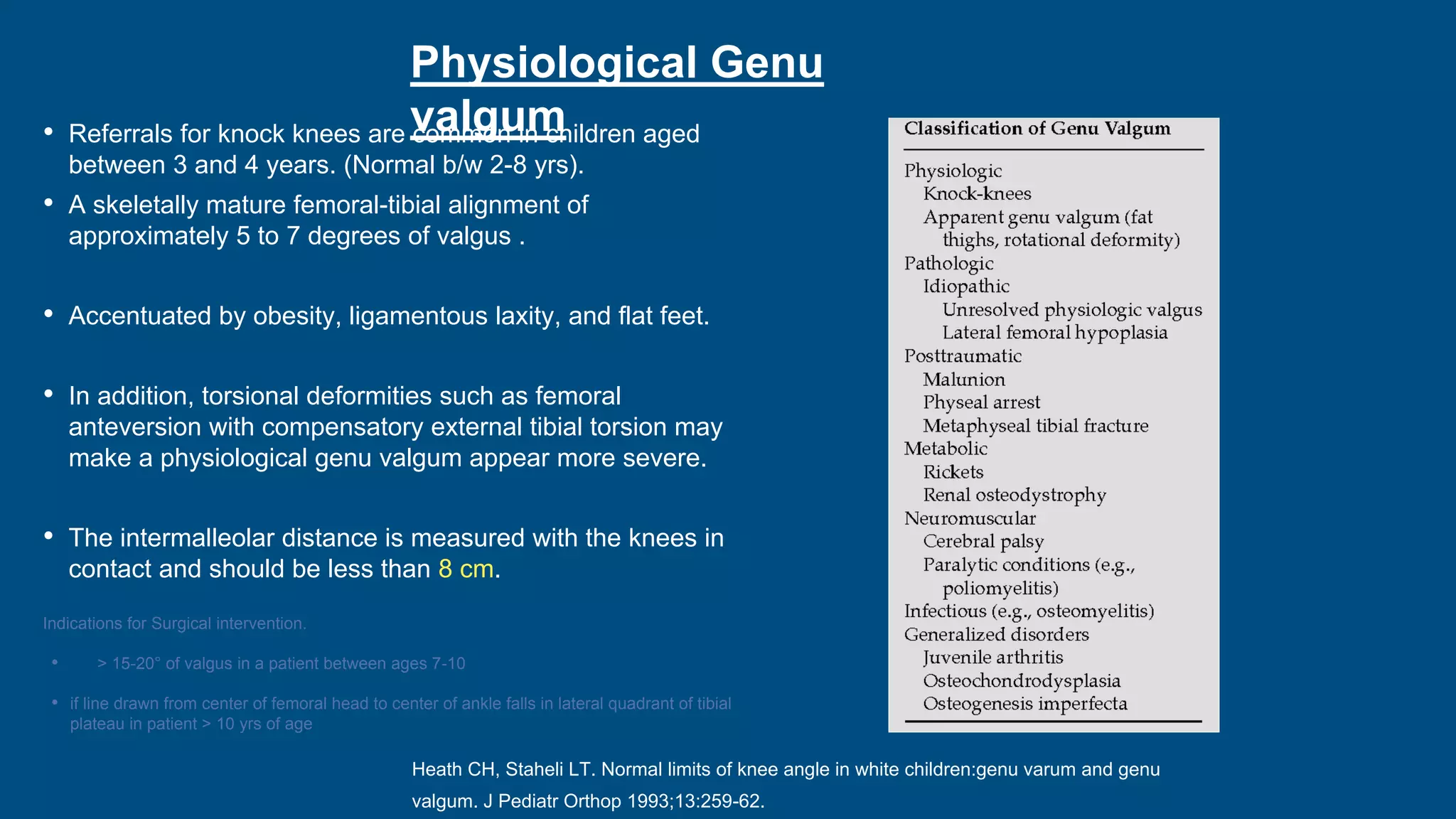

- Genu varum is normal in infants under 18 months while genu valgum peaks between 3-4 years and also typically resolves by age 7 without intervention.

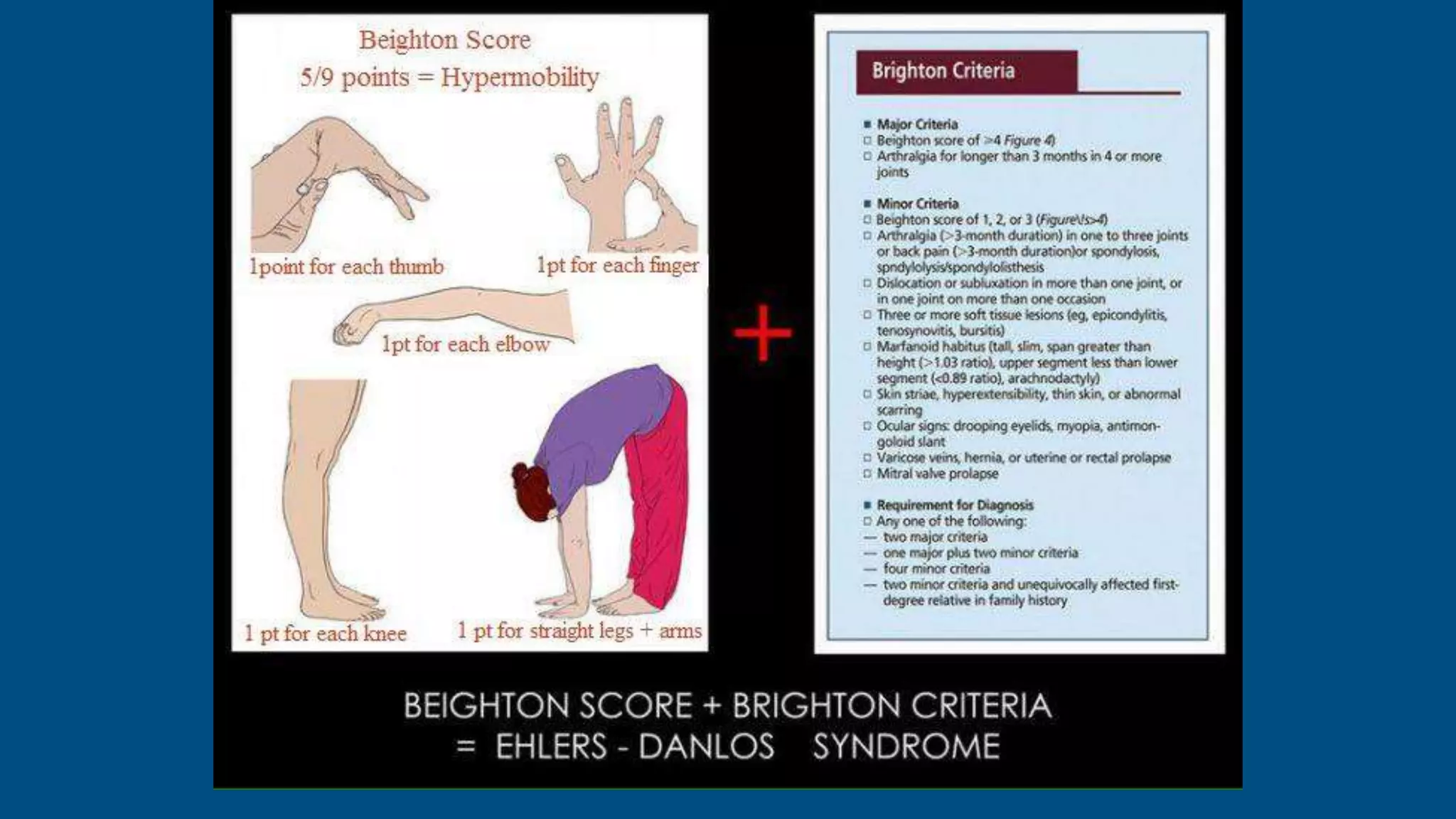

![prevalence of hypermobility in children as a phenomenon [as

opposed to joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS), i.e. symptomatic

hypermobility] depending on the age or ethnicity of the study

population or the inclusion criteria, has been reported to be

between 2.3 and 30%

Numerous extra-articular manifestations of JHS

have been similarly reported in children,

including

• chronic constipation and encopresis, enuresis

and urinary tract infections (UTI)

• higher skin extensibility

• lower systemic blood pressure

• lower bone quantitative ultrasound

measurements

• chronic fatigue syndrome

• temporomandibular joint disease

• fibromyalgia

• gross motor developmental delay](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/normalvariationsinchildren-211029163454/75/Normal-variations-in-children-44-2048.jpg)