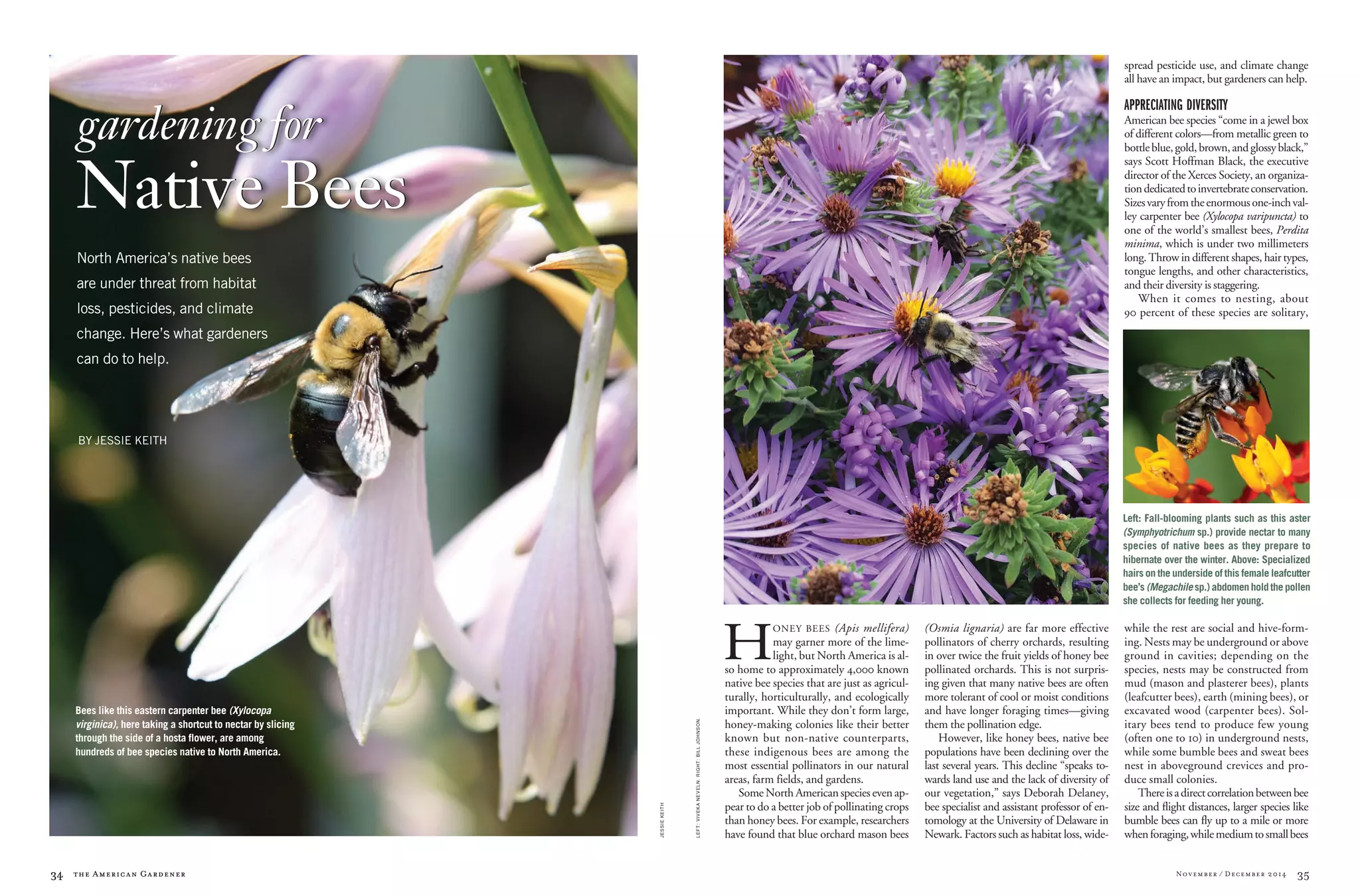

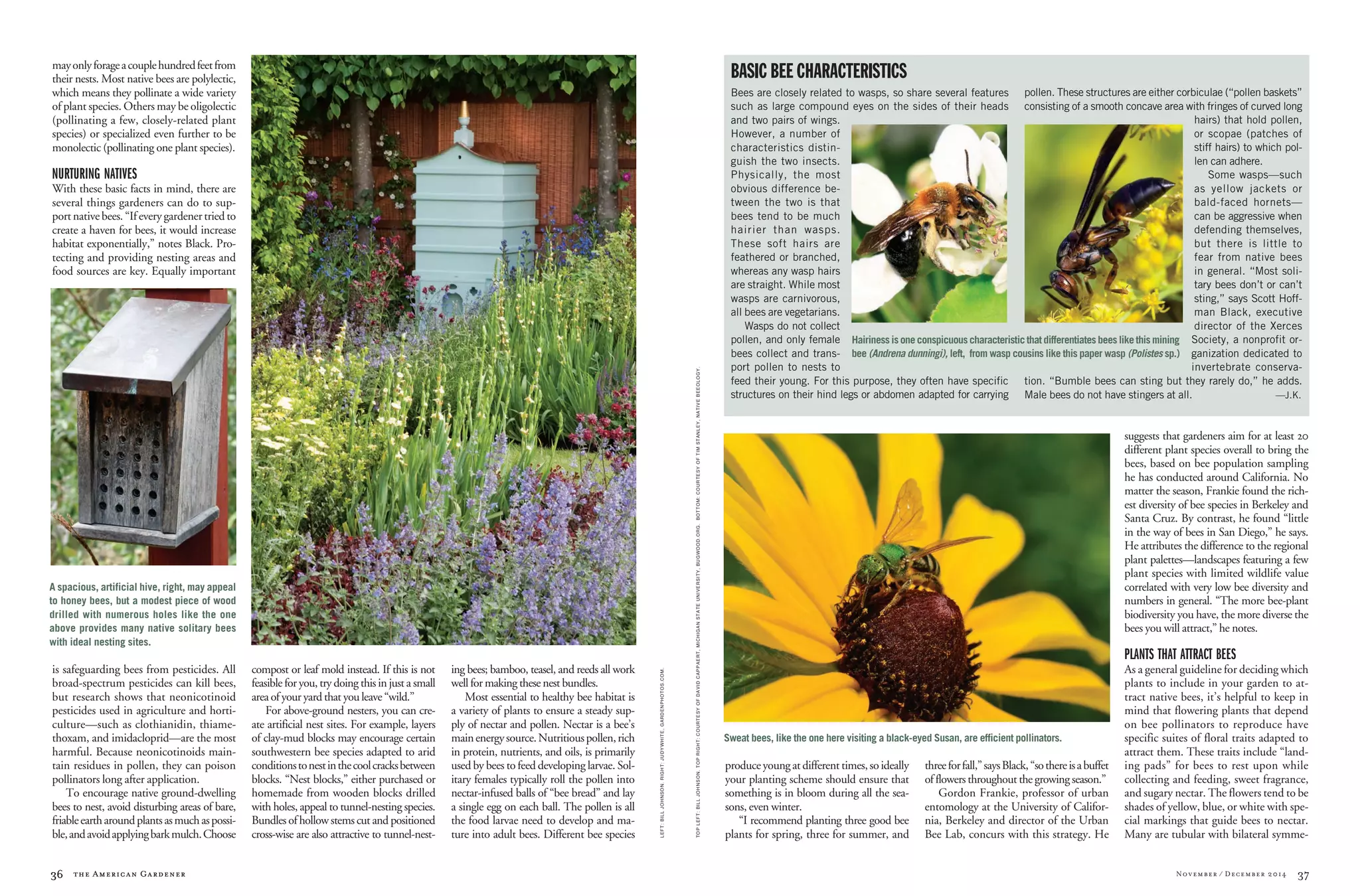

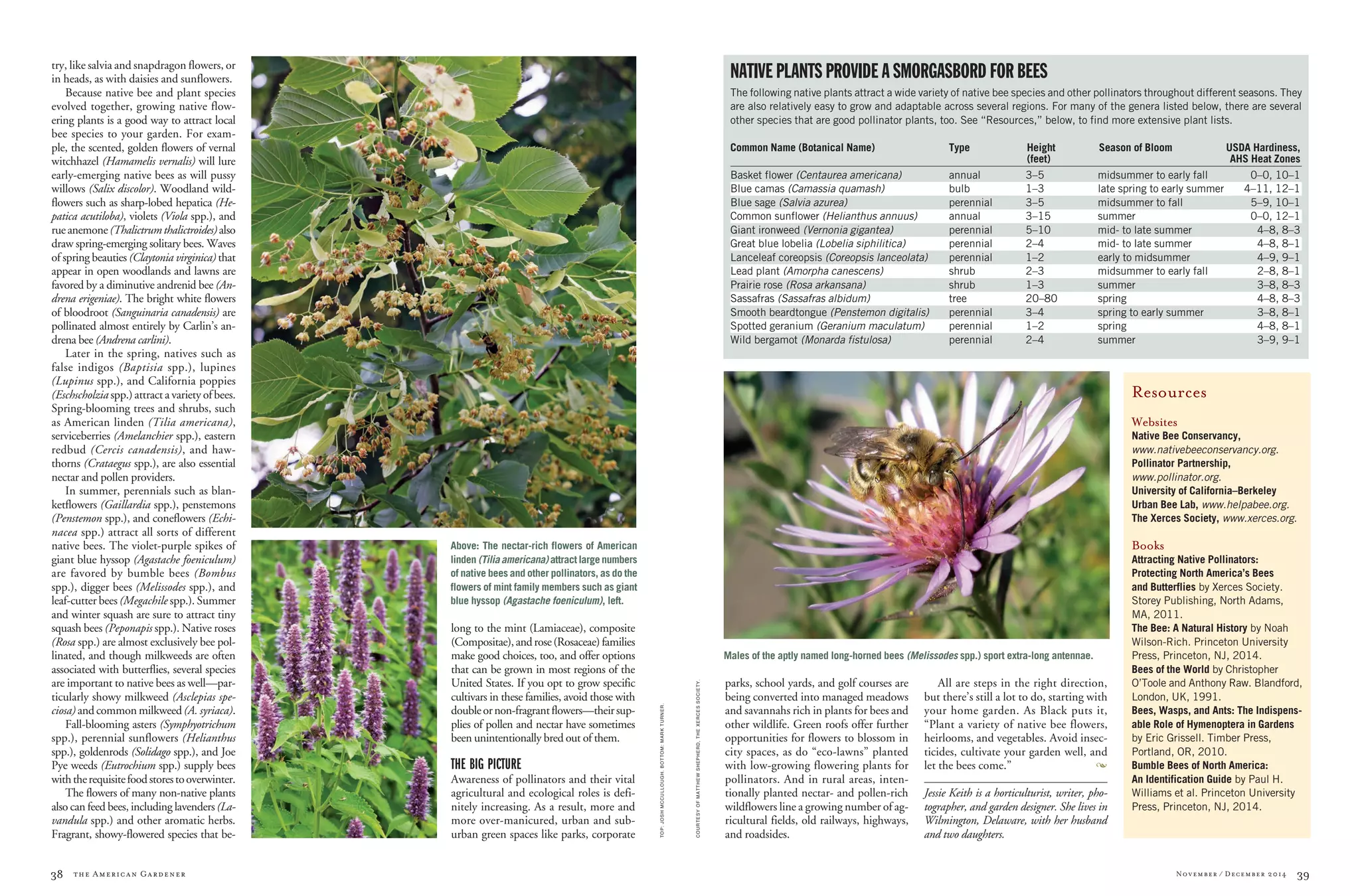

This document discusses native bee species in North America and ways that gardeners can support their populations. It notes that native bee populations are declining due to factors like habitat loss and pesticide use. Gardeners can help by planting a variety of native plants that provide a continuous supply of pollen and nectar throughout the seasons. Specific plant genera that attract bees are recommended. The document also suggests providing nesting areas for ground-nesting and cavity-nesting bees to support native bee populations in home gardens.