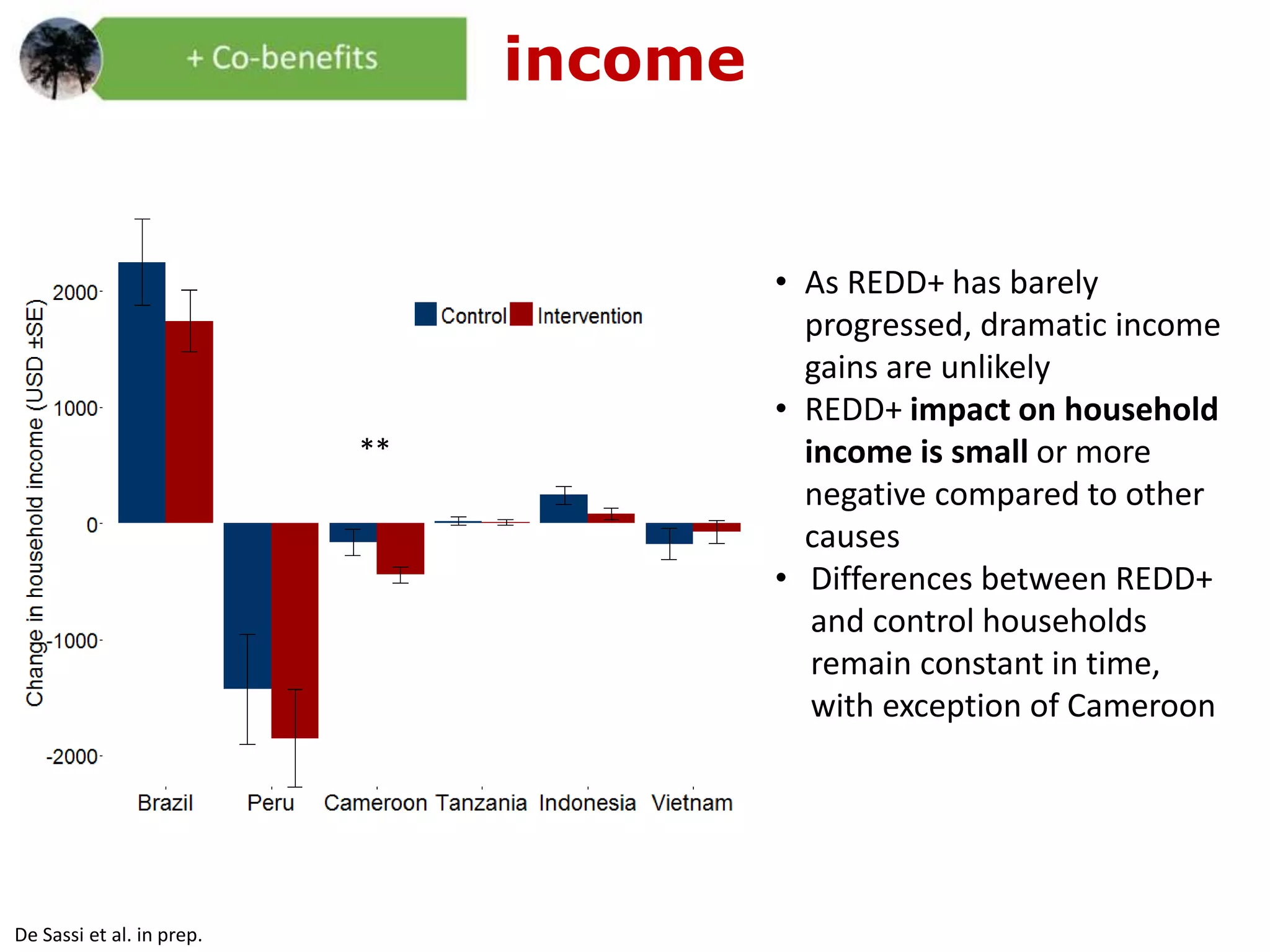

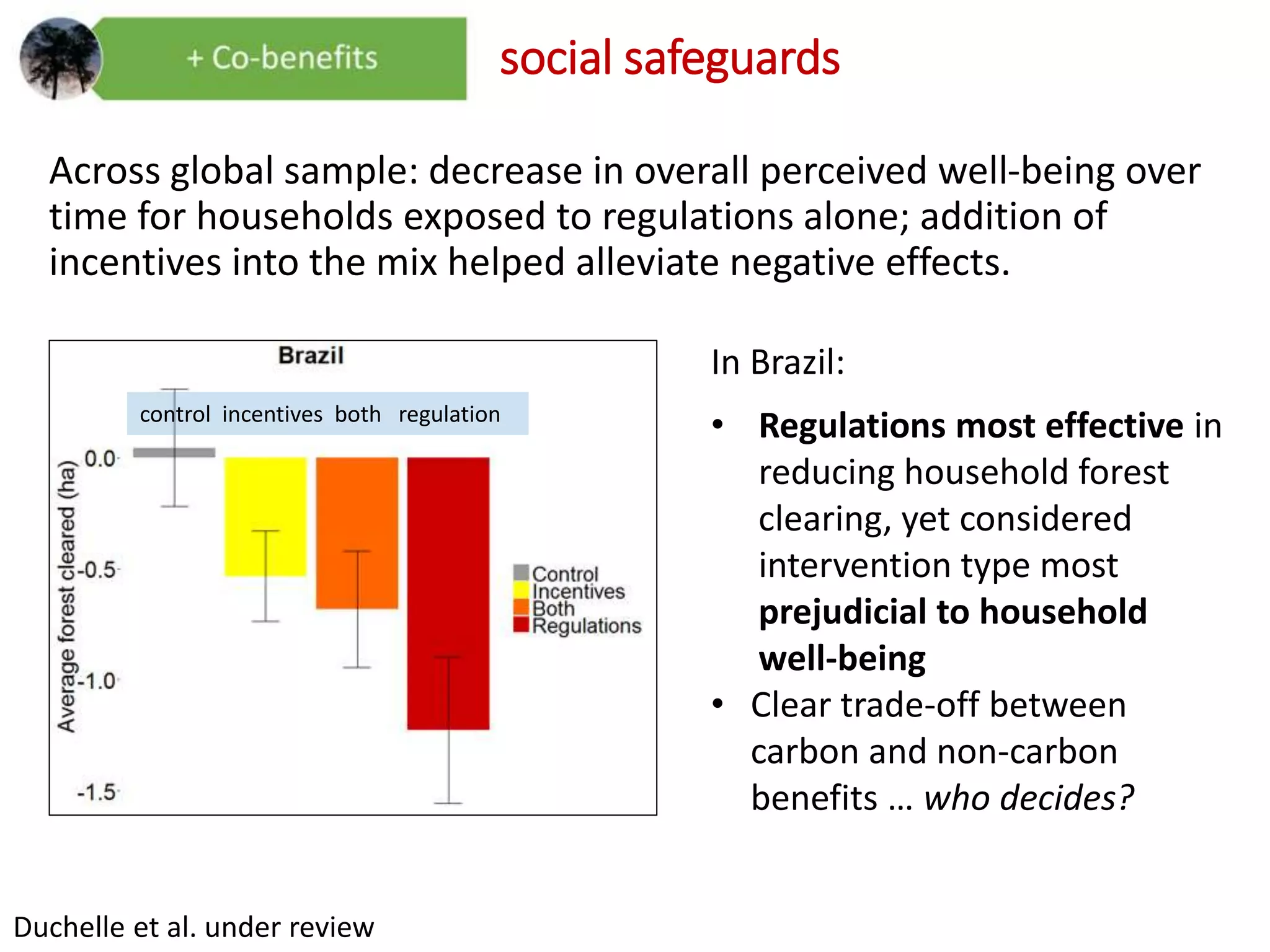

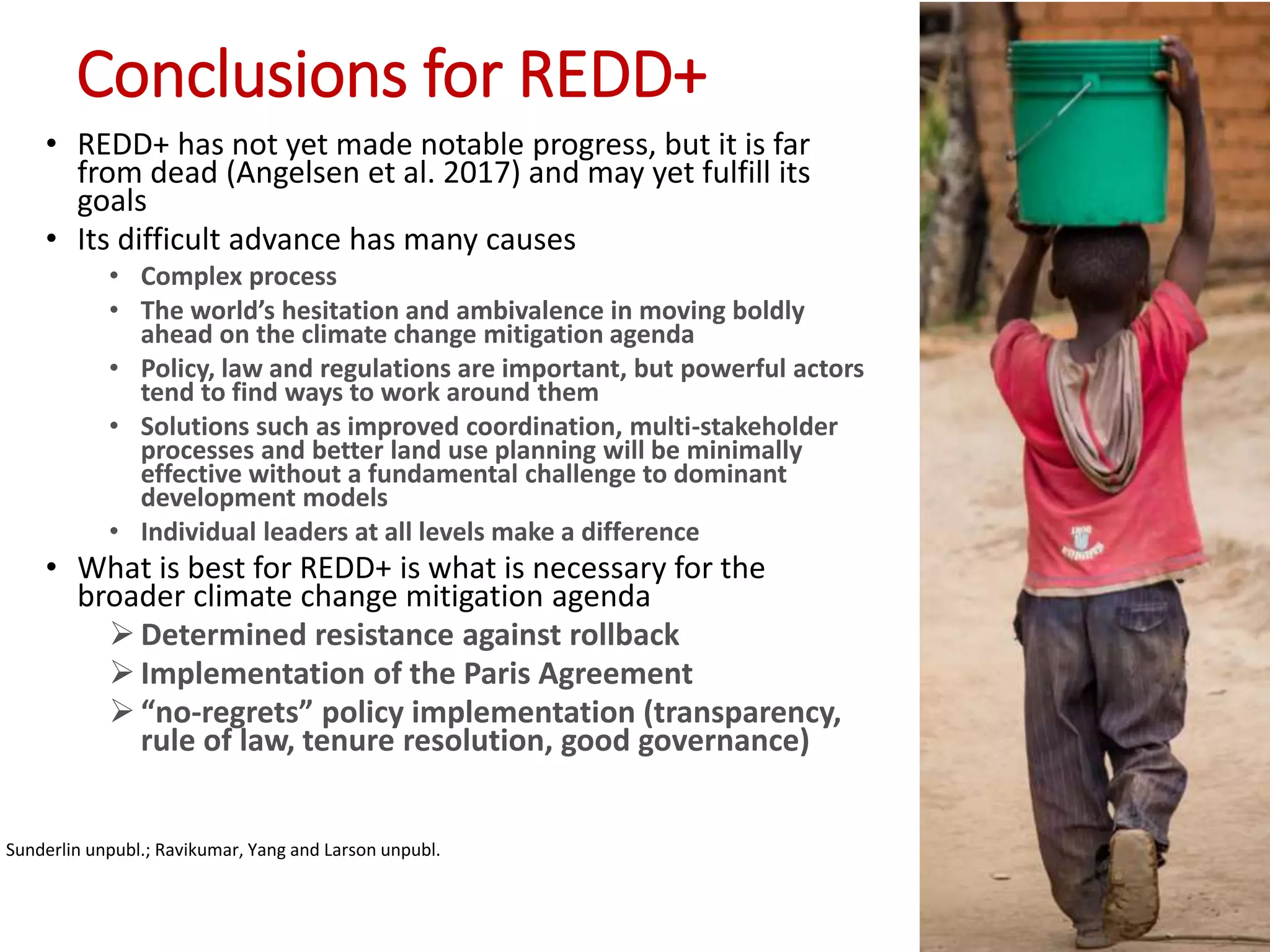

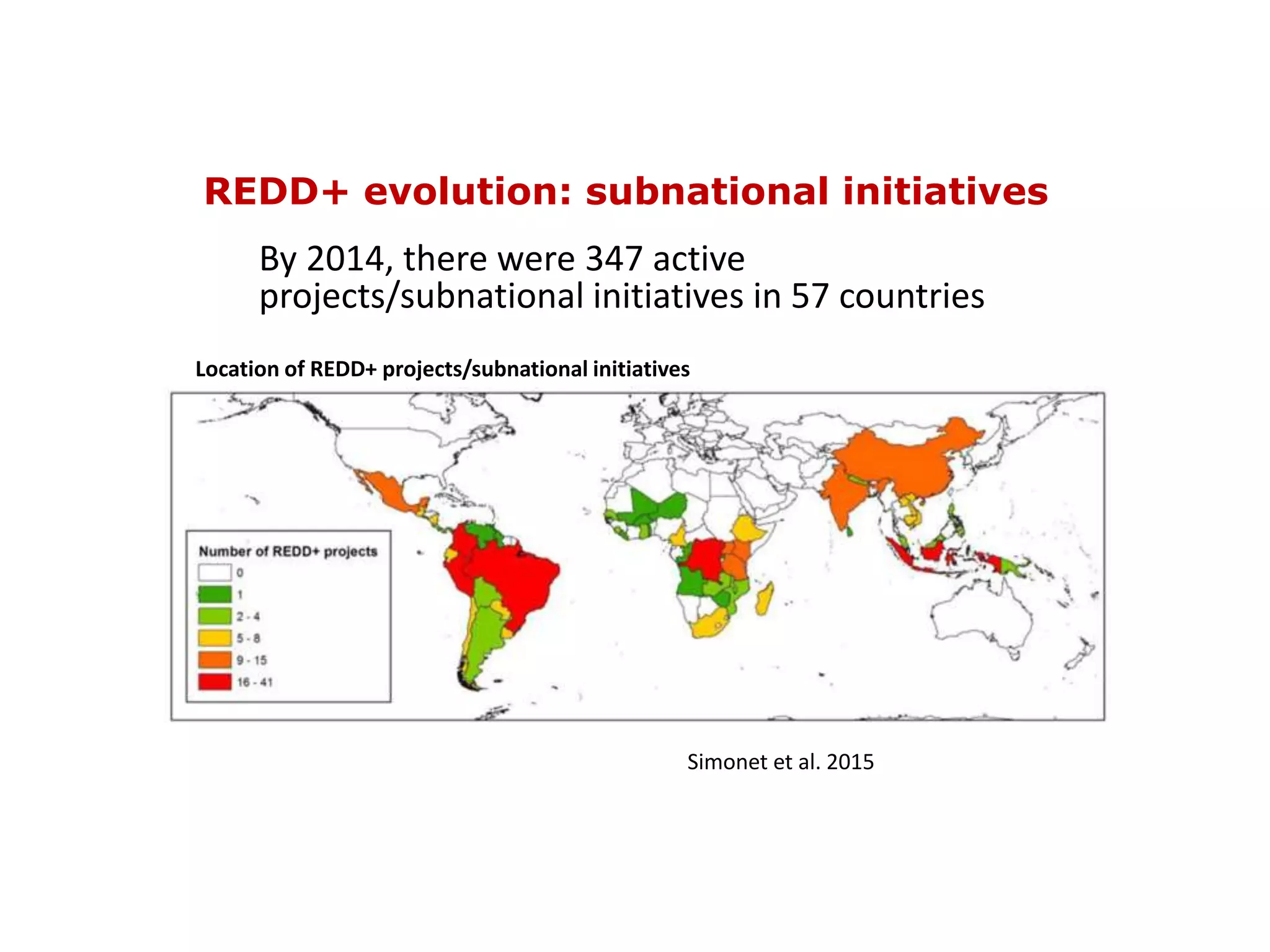

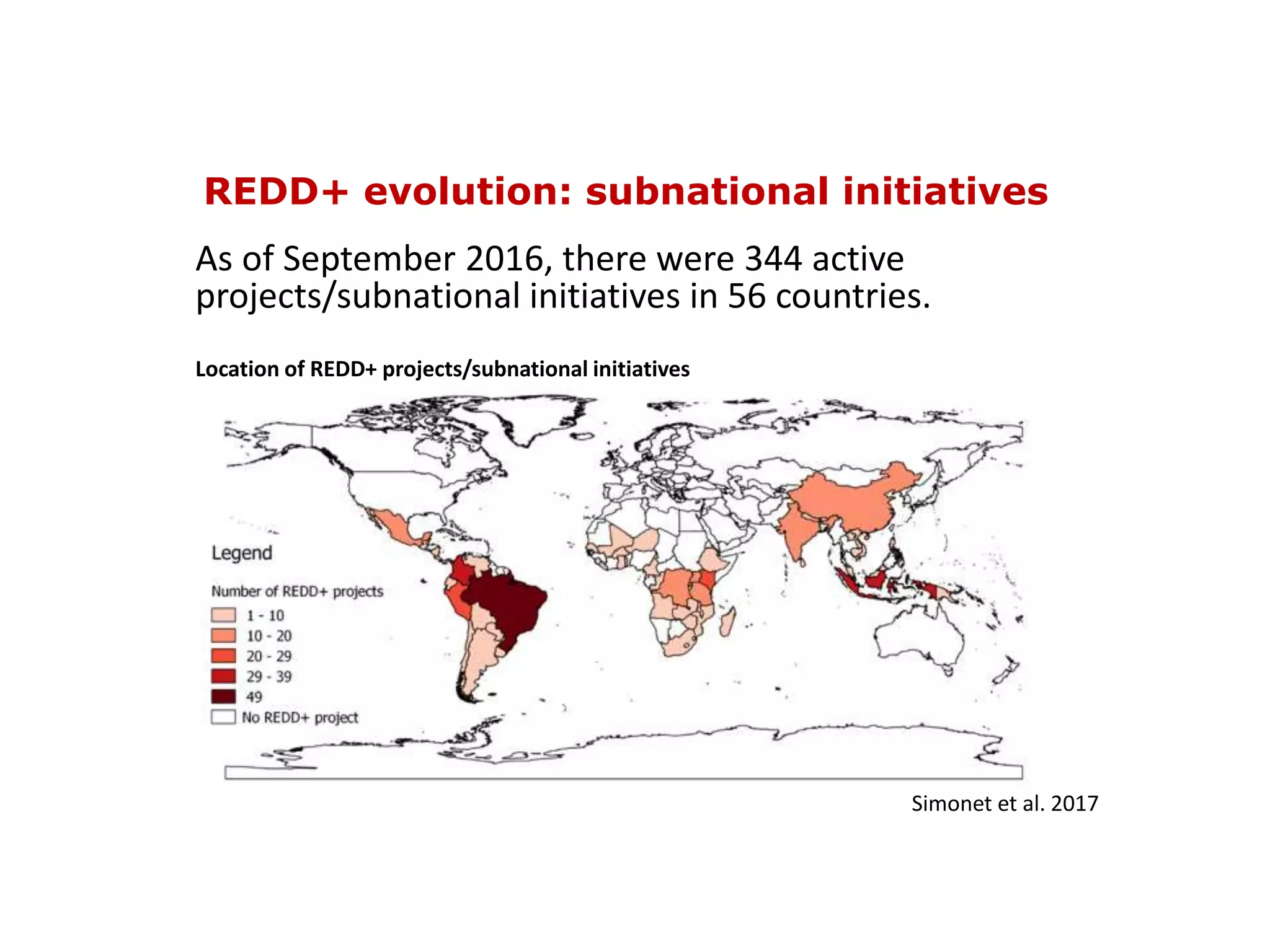

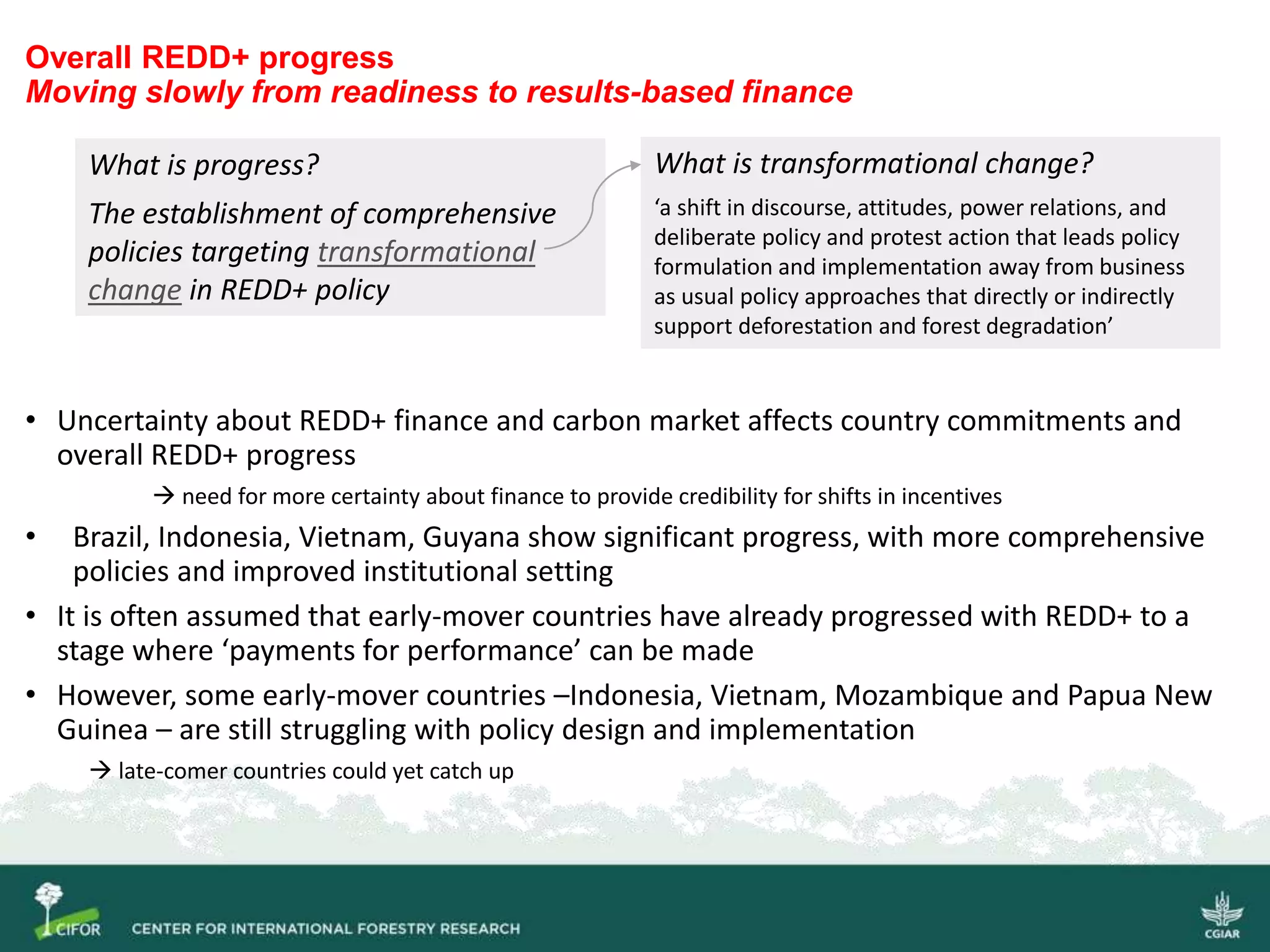

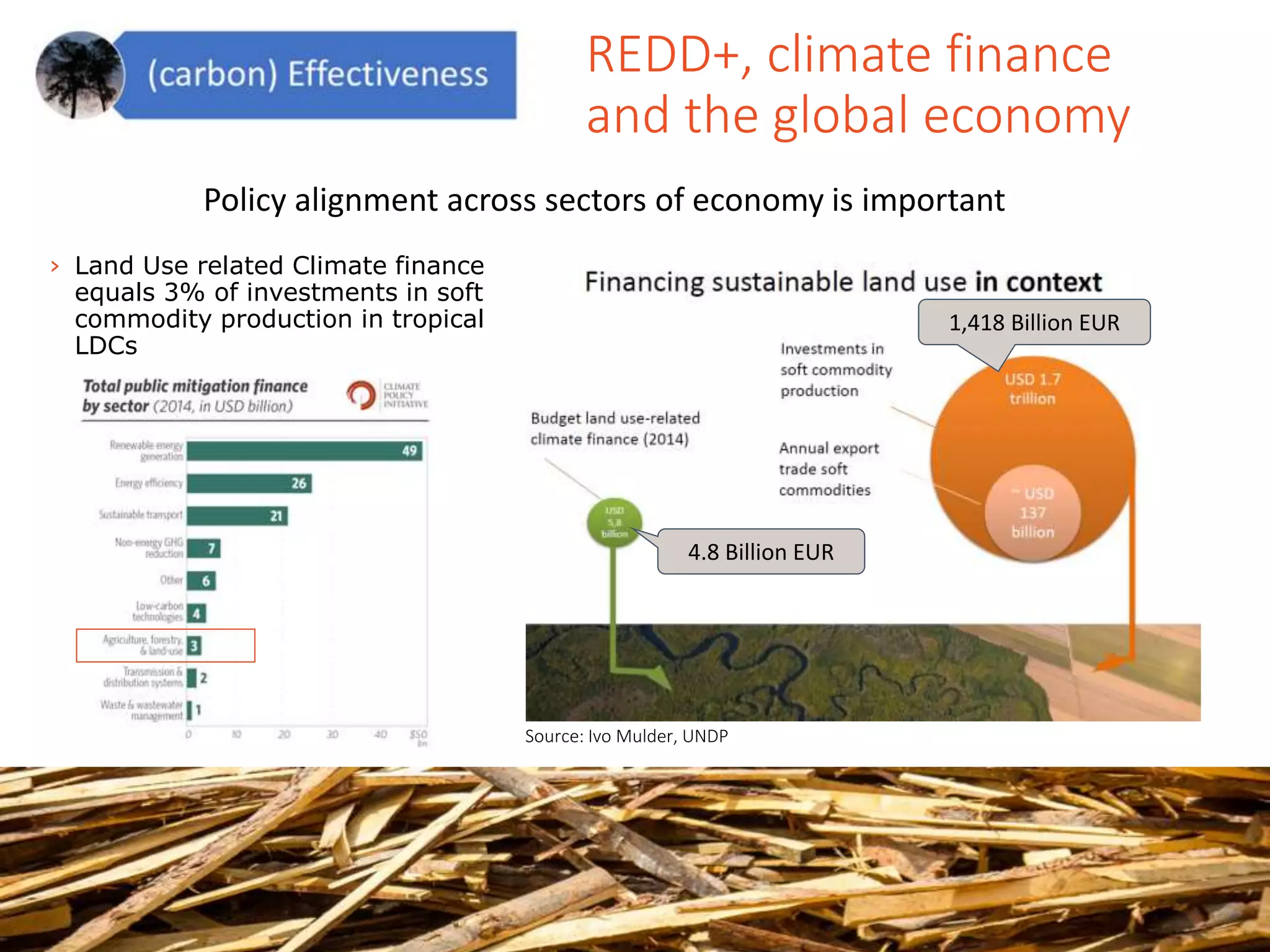

The document discusses REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) and its evolution in global climate policy since its inception. It highlights lessons learned from various countries, the effectiveness of implementation, and the importance of addressing social equity and co-benefits for local communities. Overall, while progress has been slow and challenges remain, there is potential for REDD+ to contribute to climate change mitigation efforts if it aligns with local needs and involves stakeholder engagement.

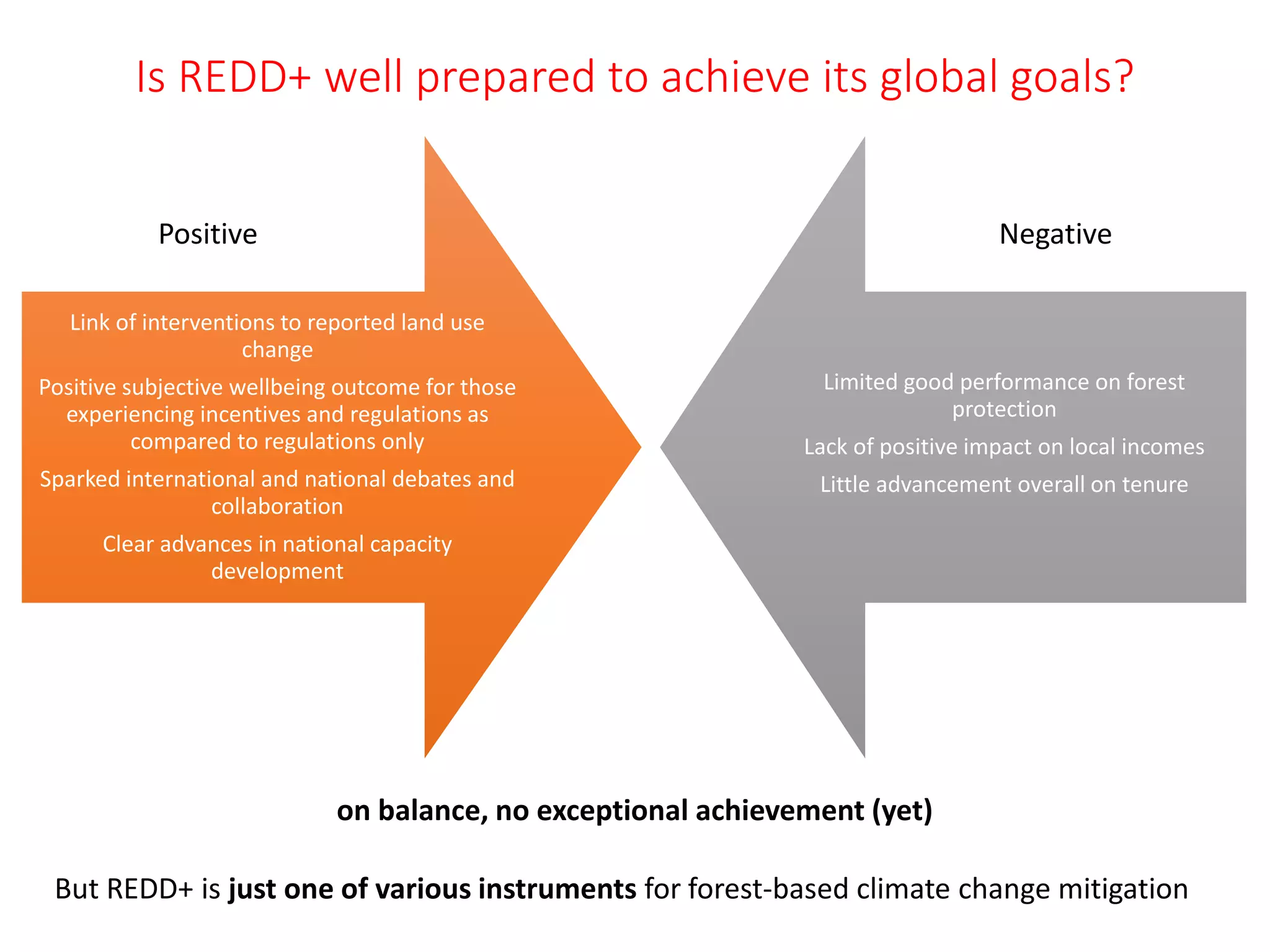

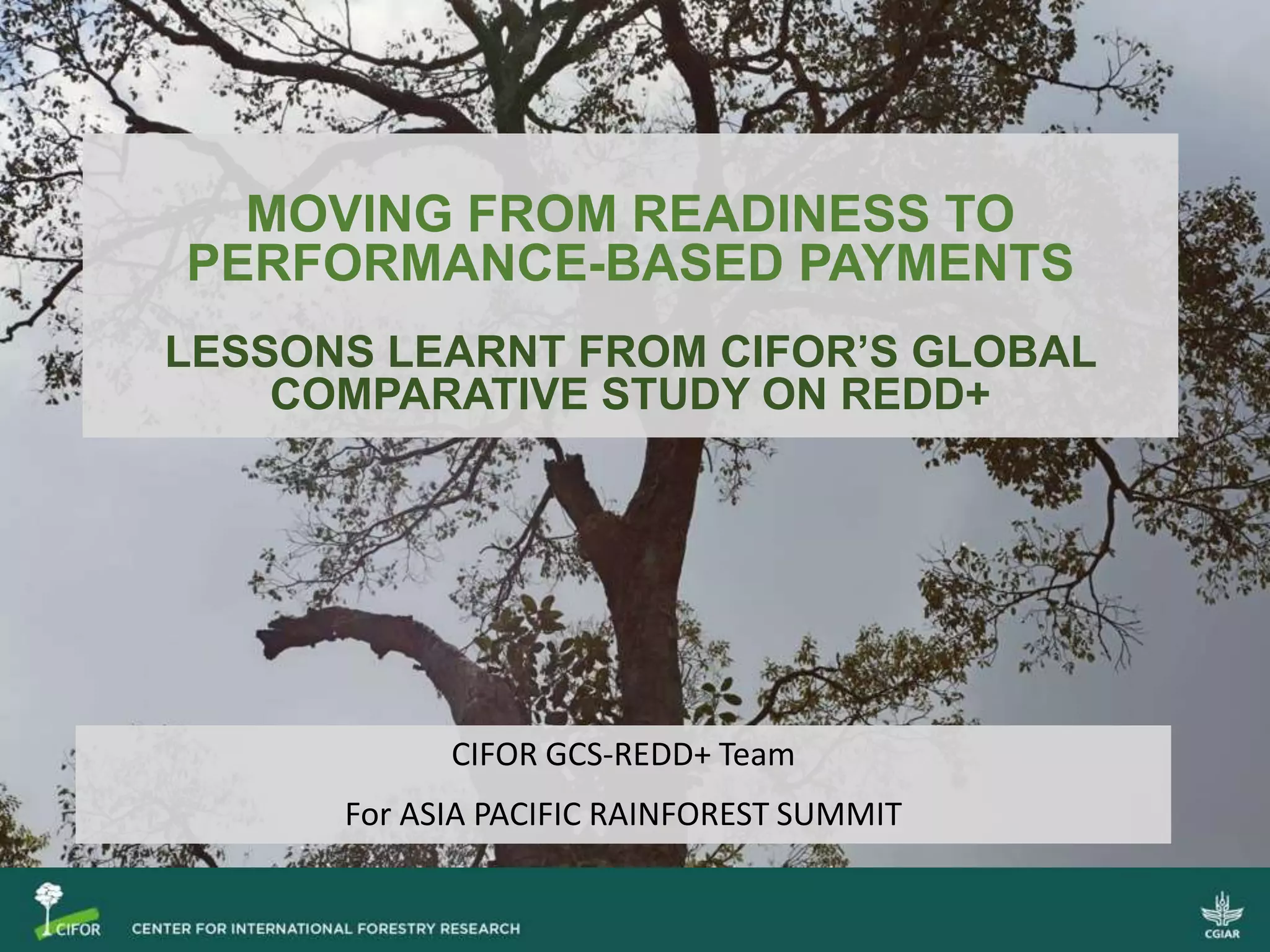

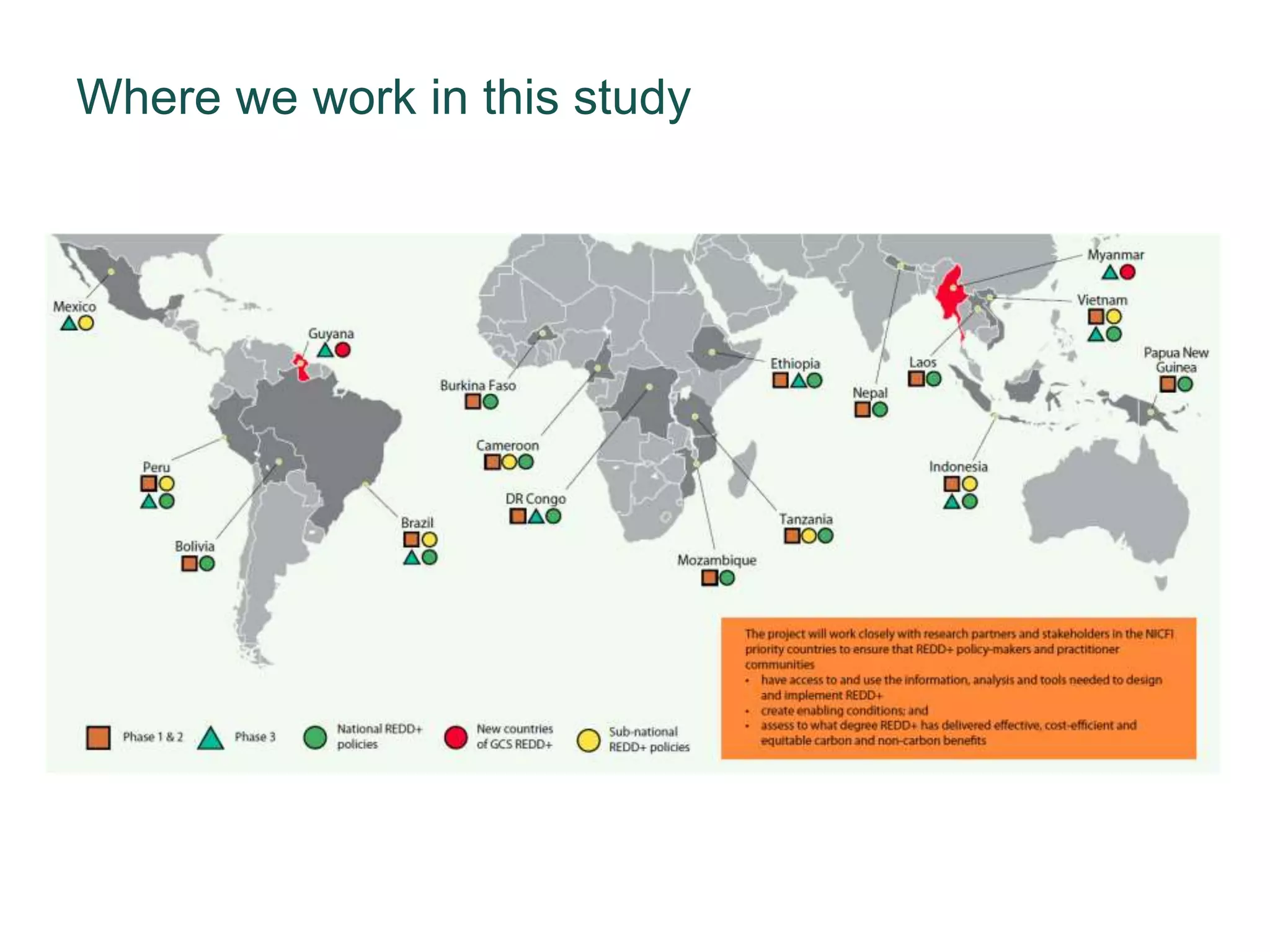

![Compensating forest users for the opportunity costs of foregoing deforestation

and degradation?

• Opportunity costs per t CO2 from deforestation

• were less than the social cost ($36) of carbon emissions in 16 of 17

sites

• compensating households to reduce emissions makes economic

sense from a global perspective in all but one Tanzanian site

• were higher than the 2015 voluntary market carbon price in 11 of 17

sites ($3.30)

• Poorer households

• had lower opportunity costs from deforestation and degradation

• would benefit more than rich households from flat payments

Ickowitz et al. 2017

We estimated smallholder opportunity costs of REDD+ for 17 sites in 6 countries

Country (number of

initiatives)

Annual OC

[US$ per tonne C ]

Brazil (5) 0.95-6.89

Peru (2) 0.61-5.91

Cameroon (2) 1.72-6.44

Tanzania (2) [dry forests

– low C density]

9.59-84.29

Indonesia (5) 0.95-2.78

Vietnam (1) 1.94

opportunity costs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmaprsdraft-180515043249/75/Moving-from-readiness-to-performance-based-payments-23-2048.jpg)