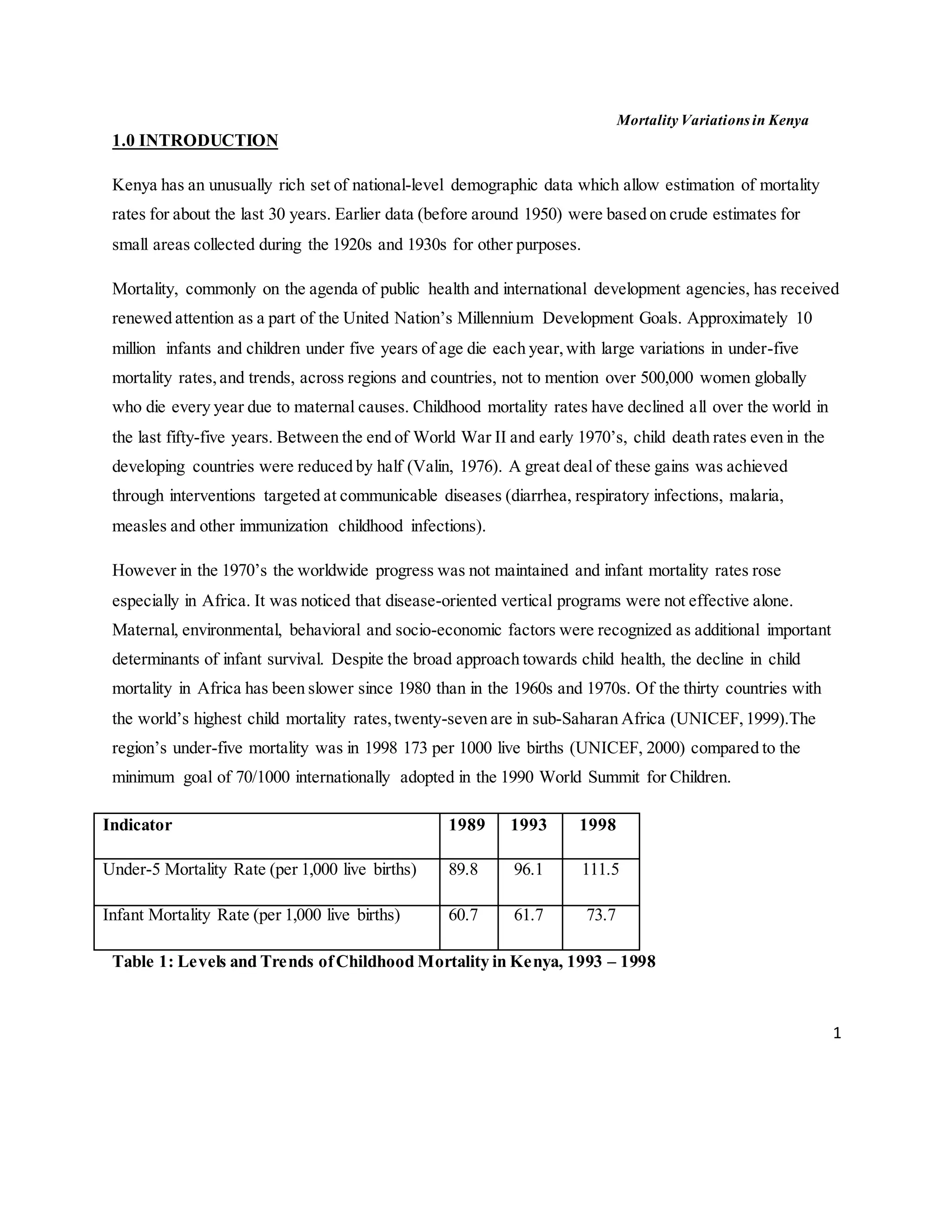

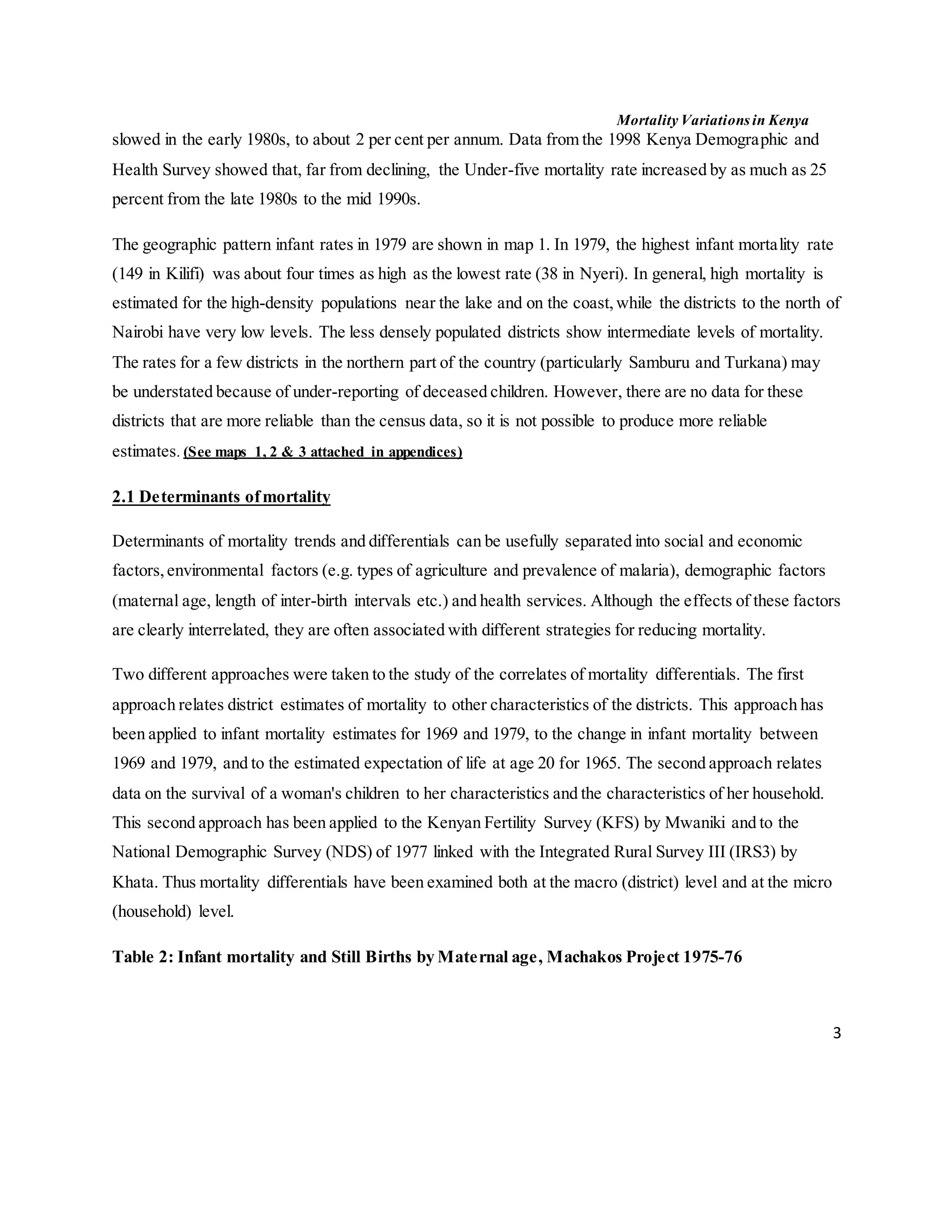

The document discusses mortality variations in Kenya, highlighting trends in childhood and maternal mortality rates over the past 30 years. Despite global declines in child mortality, sub-Saharan Africa, including Kenya, continues to experience high rates due to various socio-economic, environmental, and healthcare factors. The text emphasizes the importance of holistic approaches in addressing these mortality rates, particularly focusing on determinants like education, healthcare access, and living conditions.