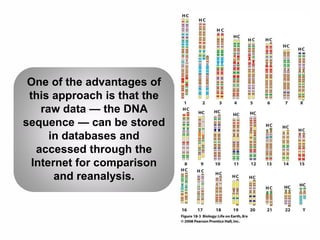

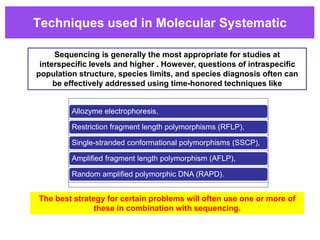

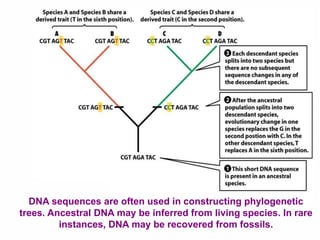

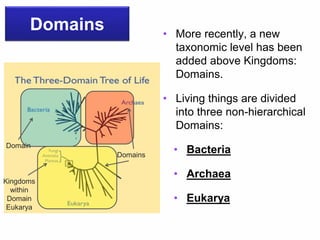

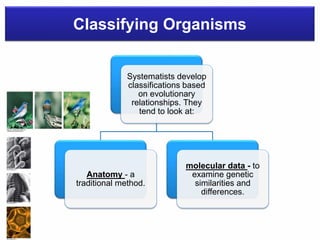

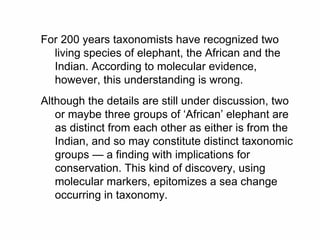

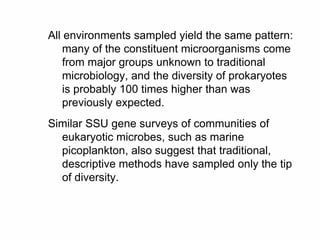

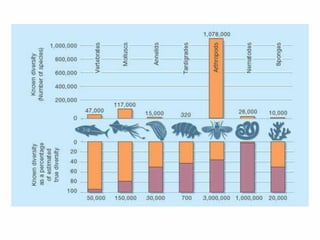

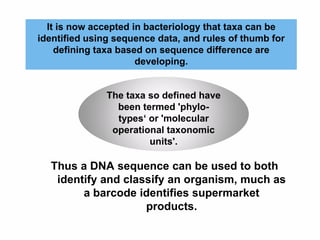

The document discusses the advancements in molecular systematics and biodiversity, emphasizing the need to classify organisms based on evolutionary relationships using molecular data. It highlights the limitations of traditional classification methods and advocates for the implementation of DNA barcoding to assess biodiversity accurately. The paper outlines the potential of modern techniques in revealing hidden diversity among species, particularly in less-studied groups, and the importance of databases for managing genetic data.

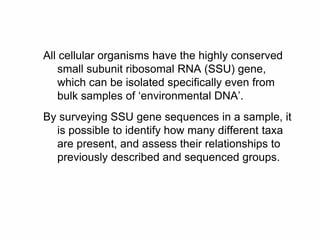

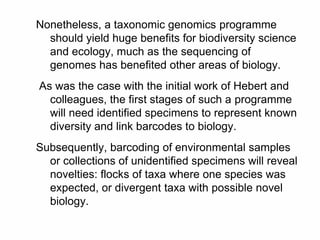

![Animals: 440555 Public BINs

Acanthocephala [64]

Annelida [6553]

Arthropoda [379269]

Brachiopoda [36]

Bryozoa [293]

Chaetognatha [68]

Chordata [32706]

Cnidaria [1043]

Cycliophora [0]

Echinodermata [1764]

Gnathostomulida [10]

Hemichordata [7]

Mollusca [15505]

Nematoda [724]

Nemertea [262]

Other Life: 3179 Public BINs

Heterokontophyta [373]

Rhodophyta [2806]

Onychophora [130]

Platyhelminthes [676]

Porifera [485]

Priapulida [2]

Rotifera [690]

Sipuncula [107]

Tardigrada [156]

Xenoturbellida [5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sarwar11518-200327031145/85/Molecular-Systematics-and-Biodiversity-22-320.jpg)