This document provides an overview of a basic professional training course on nuclear physics and reactor theory. It covers topics like atomic structure, the structure of the atom including electrons and the nucleus, isotopes, radioactive decay, and nuclear reactions. The document is divided into several modules, with learning objectives provided for each section. It includes diagrams and examples to illustrate key concepts in nuclear physics.

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Energy levels in nuclei

• Nucleons can occupy different energy levels

− All nucleons in lowest possible energy levels: ground state

− Nucleons in higher energy levels: excited state

27

ground

state

energy

[MeV]

a) b)

0

etc.

etc.

0 0

10

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-27-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Binding energy of a nucleon

• Average energy needed to release one nucleon from the nucleus

28

-9

-8

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240

binding

energy

per

nucleon

w

B

[MeV]

mass number A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-28-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

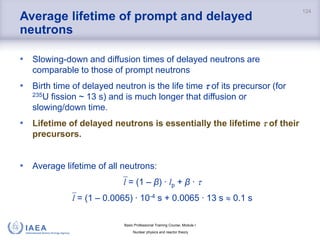

Dependence of reactor period on reactivity

• the graph shows absolute

values of reactivity and reactor

period

• the shortest negative period

is -80 s.

− reactor can not shut down

faster than the decay of most

long-lived precursors

126

0.001

0.01 .02 .03 .04 .06.08 .1 .2 .3 .4 .6 .8 1.0 2.0

reactivity [$]

stable

period

[s]

0.01

0.1

1

10

100

10000

80

1000

positive reactivity

positive period

negative reactivity

negative period](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-126-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

135Xe during reactor start-up

• After reactor start-up, 135Xe concentration starts to grow

• Equilibrium concentration of 135Xe approx. 40 - 50 h after start-up

− equilibrium conc. depends on reactor power, but dependence not linear

140

25%

0

0

-500

-1000

-1500

-2000

-2500

-3000

time [hours]

reactivity

due

to

Xe

[pcm]

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

50%

75%

100%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-140-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Reactivity due to 135Xe after shutdown

142

25%

0

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

-500

-1000

-1500

-2000

-2500

-3000

time [hours]

reactivity

due

to

Xe

[pcm]

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

50%

75%

100%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-142-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Critical boron concentration

• The critical boron concentration (CB) is defined as the concentration

of boron required for the reactor to be critical on full power with the

control rods withdrawn.

• Typical course of critical boron concentration over the fuel cycle:

149

4000

1000

2000

C

[ppm]

B

burn-up [MWd/MTU]

8000 12000 16000 20000](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-149-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Definition of basic quantities

Heat flux is defined as the quantity of heat per unit time:

𝑄 =

∆𝑄

∆𝑡

[J/s = W]

Heat flux density is heat flux per unit surface area [W/m2].

162

Heat is energy which passes from a point of higher temperature to

a point of lower temperature.

If there is no difference in temperature, there can be no heat transfer.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-162-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Heat conduction equation

𝑄 =

𝜆 𝐴 Δ𝑇

Δ𝑥

heat conductivity [W/mK]

A surface area of the wall [m2]

T temperature difference [K]

x wall thickness [m]

165](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-165-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Equation of heat transfer

𝑄 = ℎc 𝐴 Δ𝑇

hc heat transfer coefficient [W/m2K]

A wall surface area [m2]

T temperature difference between wall and fluid [K]

• hc depends on fluid velocity, pressure, temperature, the flow

regimes of potential two-phase flow, etc. It is determined

experimentally.

171](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-171-320.jpg)

![Basic Professional Training Course; Module I

Nuclear physics and reactor theory

Average linear power density

• thermal power released per unit fuel rod length [kW/m]

Example:

− thermal power of a PWR: 1994 MW

− number of fuel elements in the core: 121

− number of fuel rods in each element: 235

− length of fuel rod: 3.6 m

− fraction of heat released in the fuel: 97.4%

𝑞 =

1994 ∙ 1000 kW ∙ 0.974

121 ∙ 235 ∙ 3.6 m

= 18.7 kW/m

• Linear power density is not equal for all the rods in a fuel element

− varies among individual elements

− varies with the height of a fuel rod in the core

179](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module01nuclearphysicsandreactortheory-210914170036/85/Module01-nuclear-physics-and-reactor-theory-179-320.jpg)