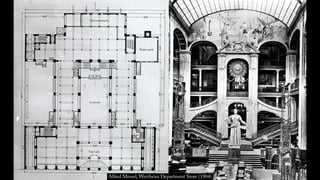

Modern surfaces focused on communication over space through signs and images rather than enclosed walls. Adolf Loos believed ornamentation of utilitarian objects should be removed and architecture should become a "living organism" rather than display superficial decoration. The Bauhaus school saw architecture sinking into decorative concepts and sought to vitalize building surfaces without becoming parasitic. Mies van der Rohe designed transparent glass skyscrapers to let light assert itself. Department stores and advertisements used stimulating visual displays to attract consumers in an era when supply exceeded demand.