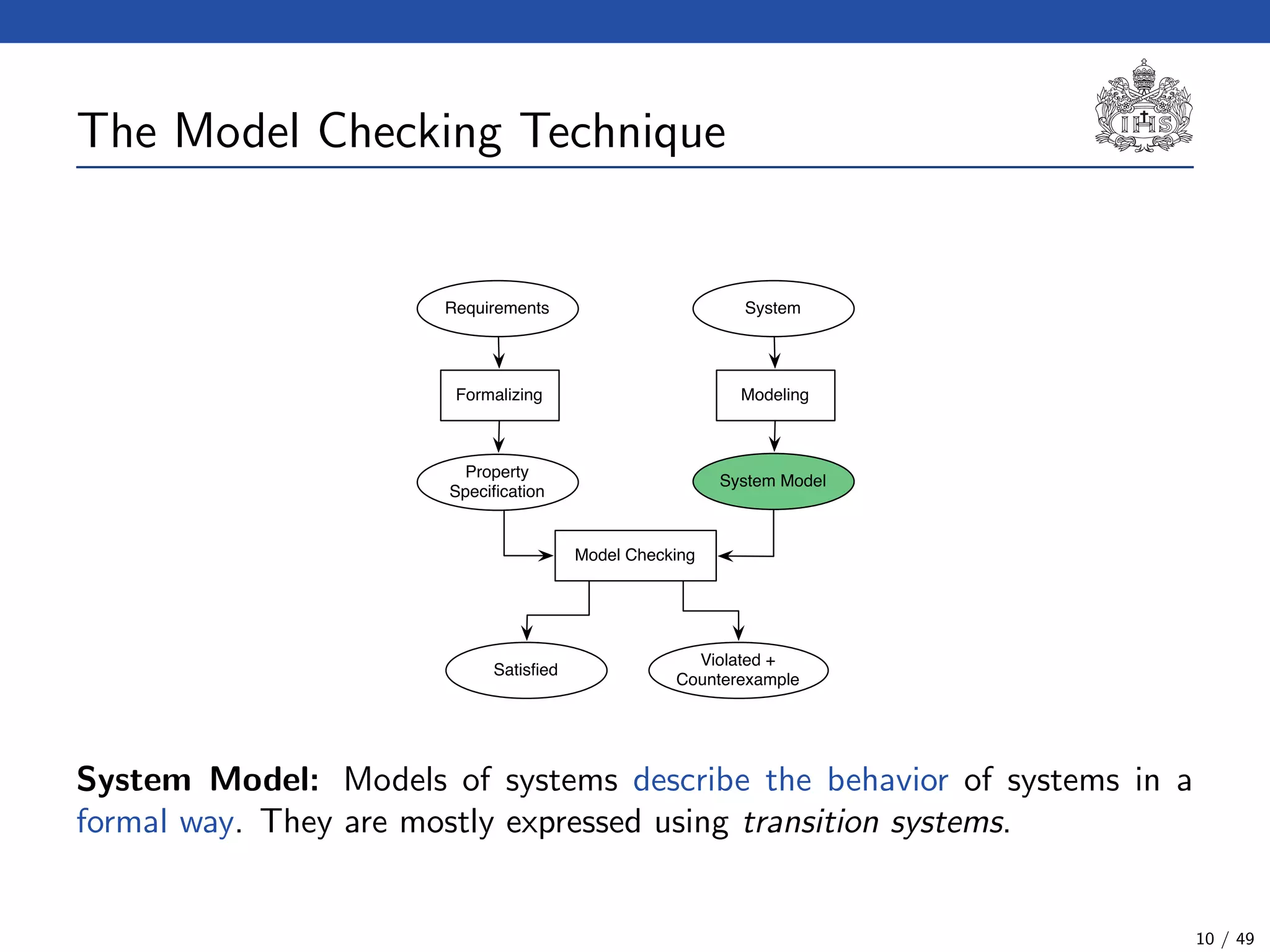

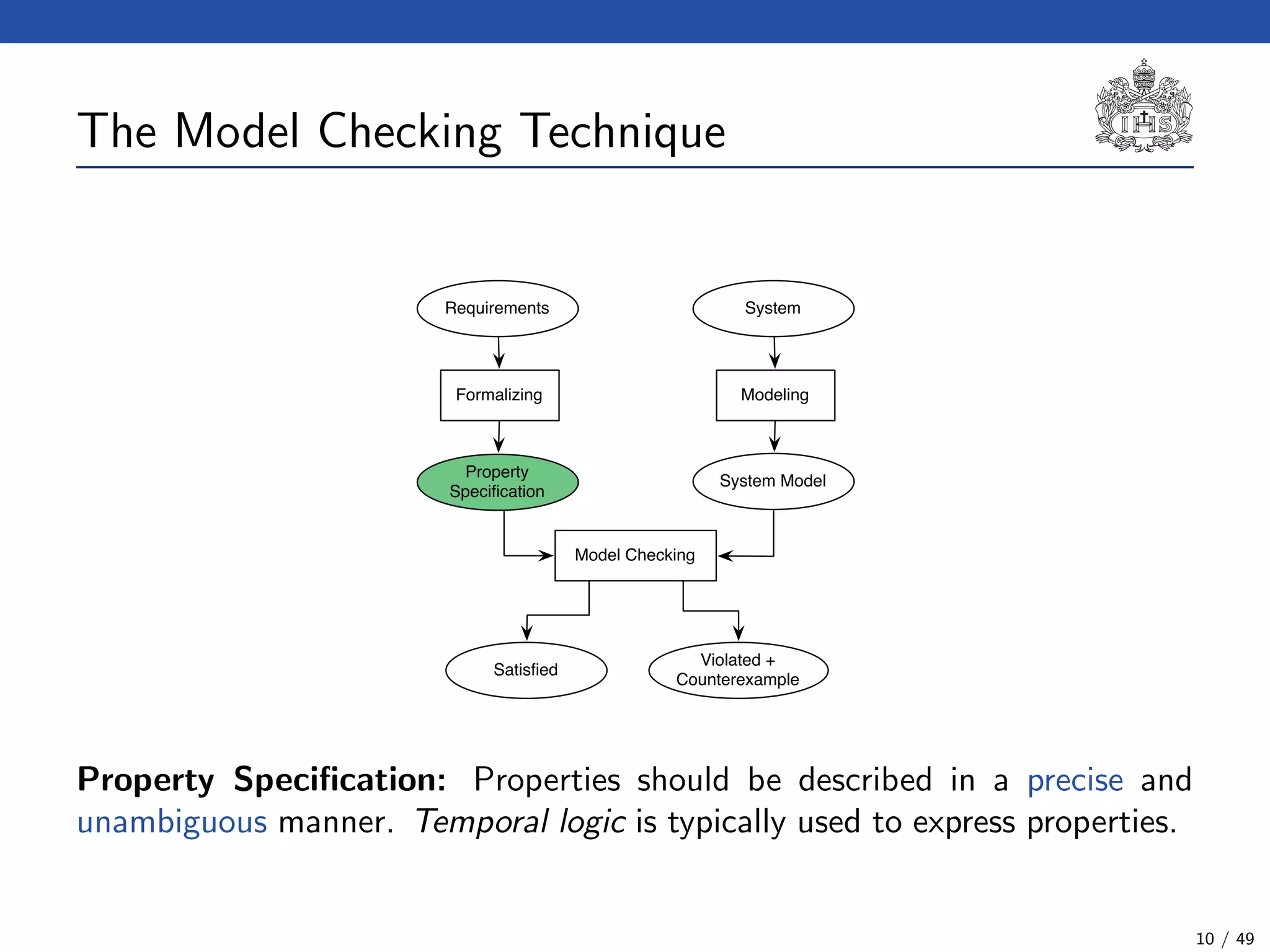

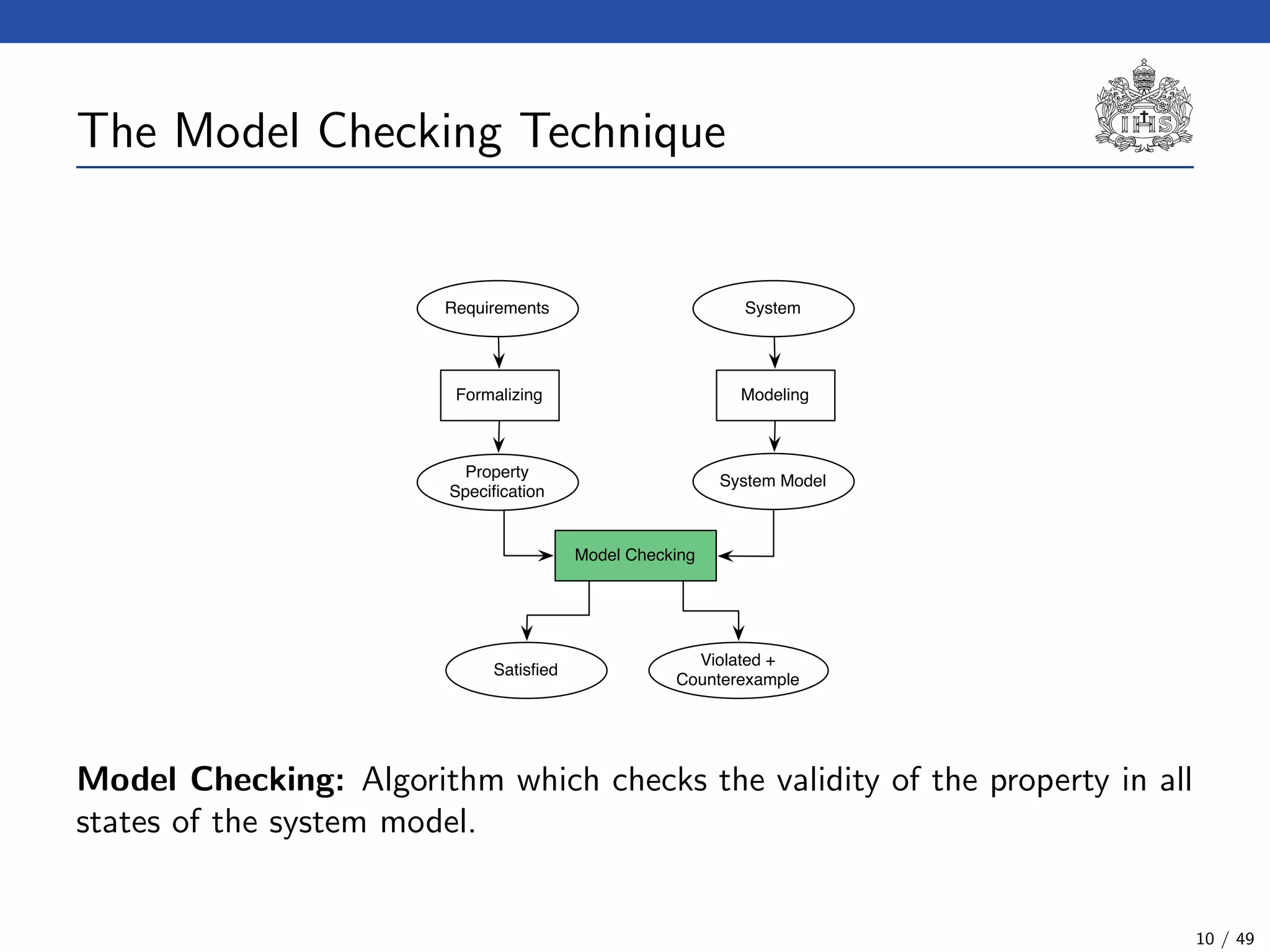

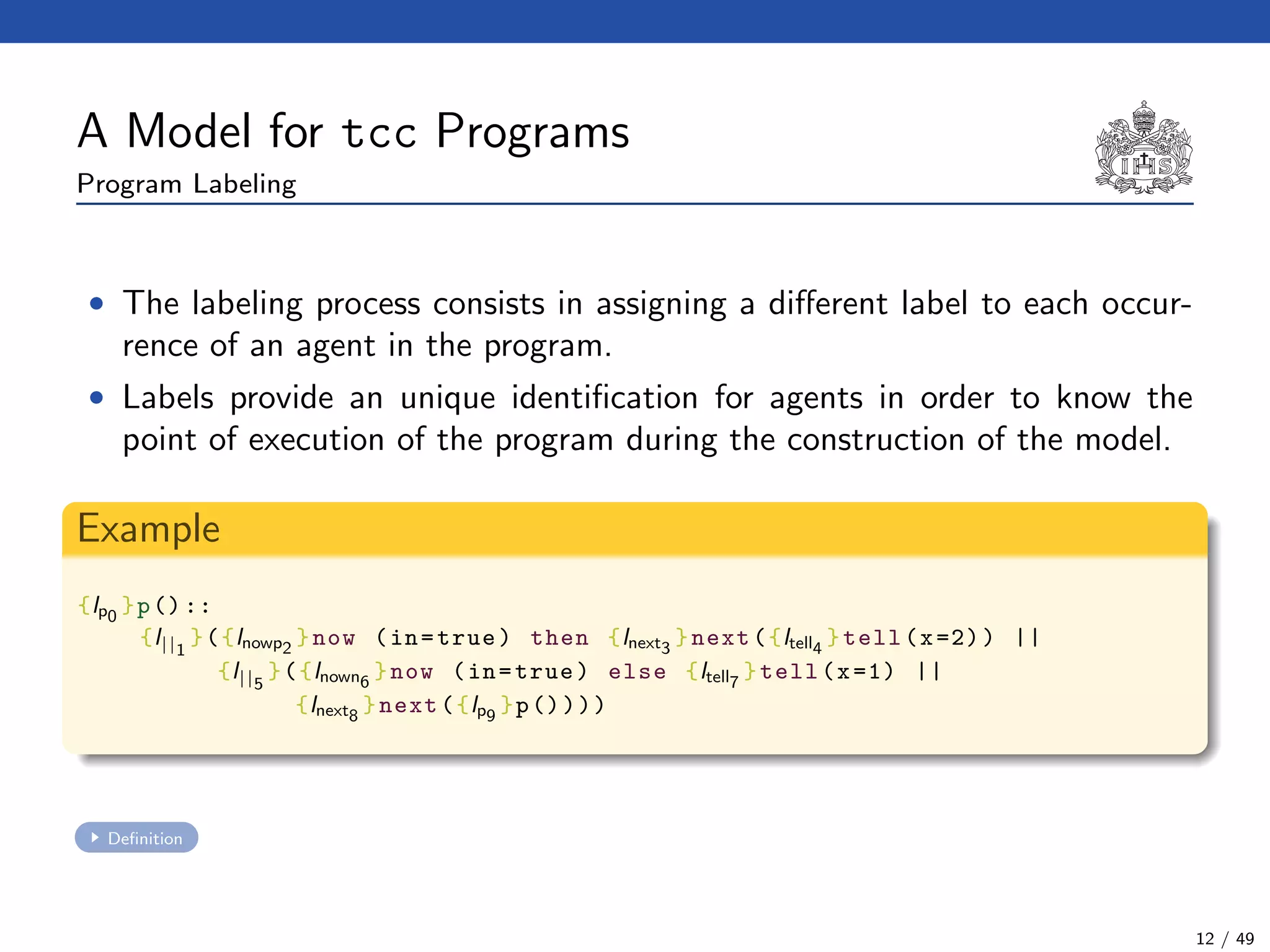

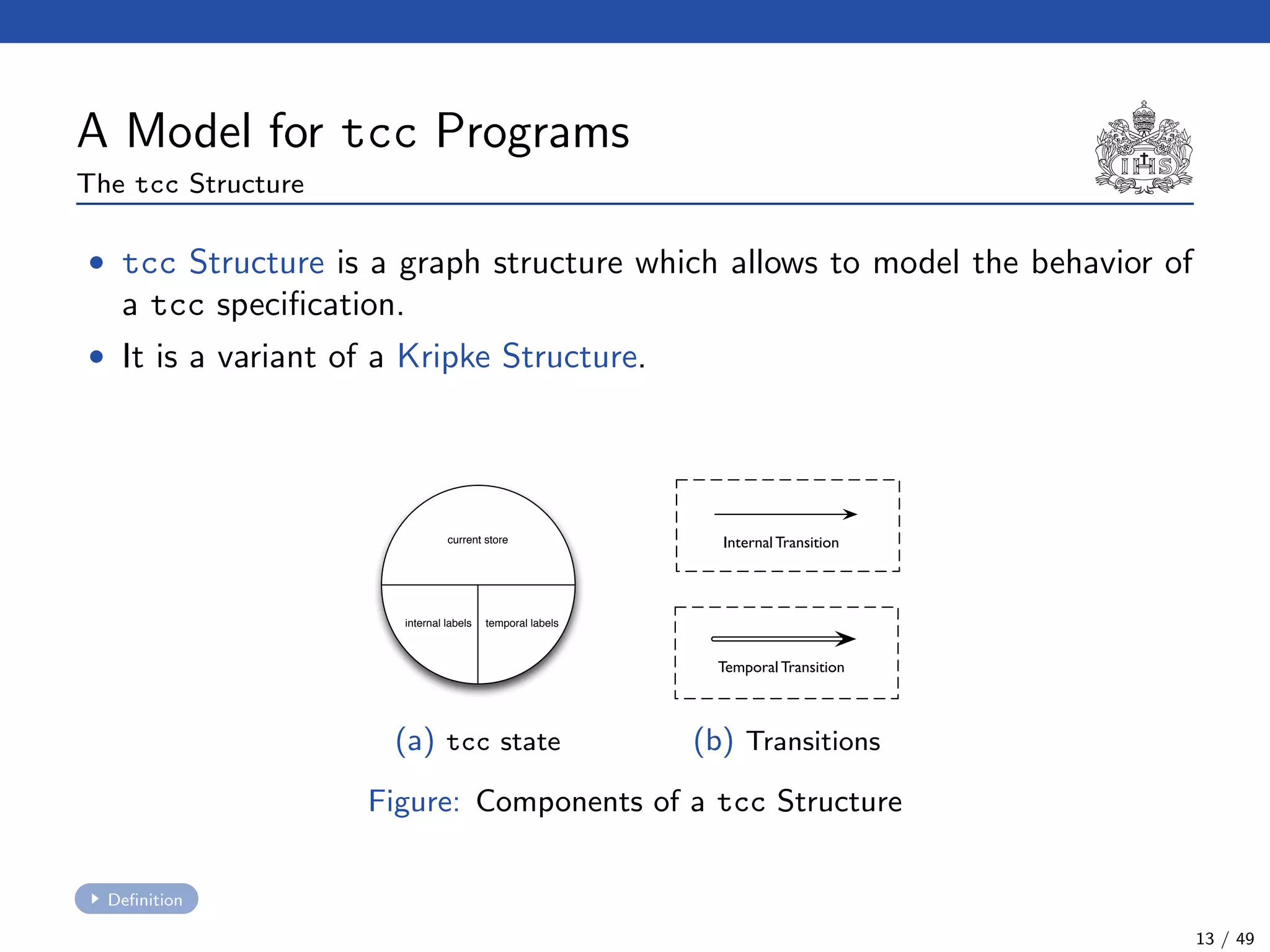

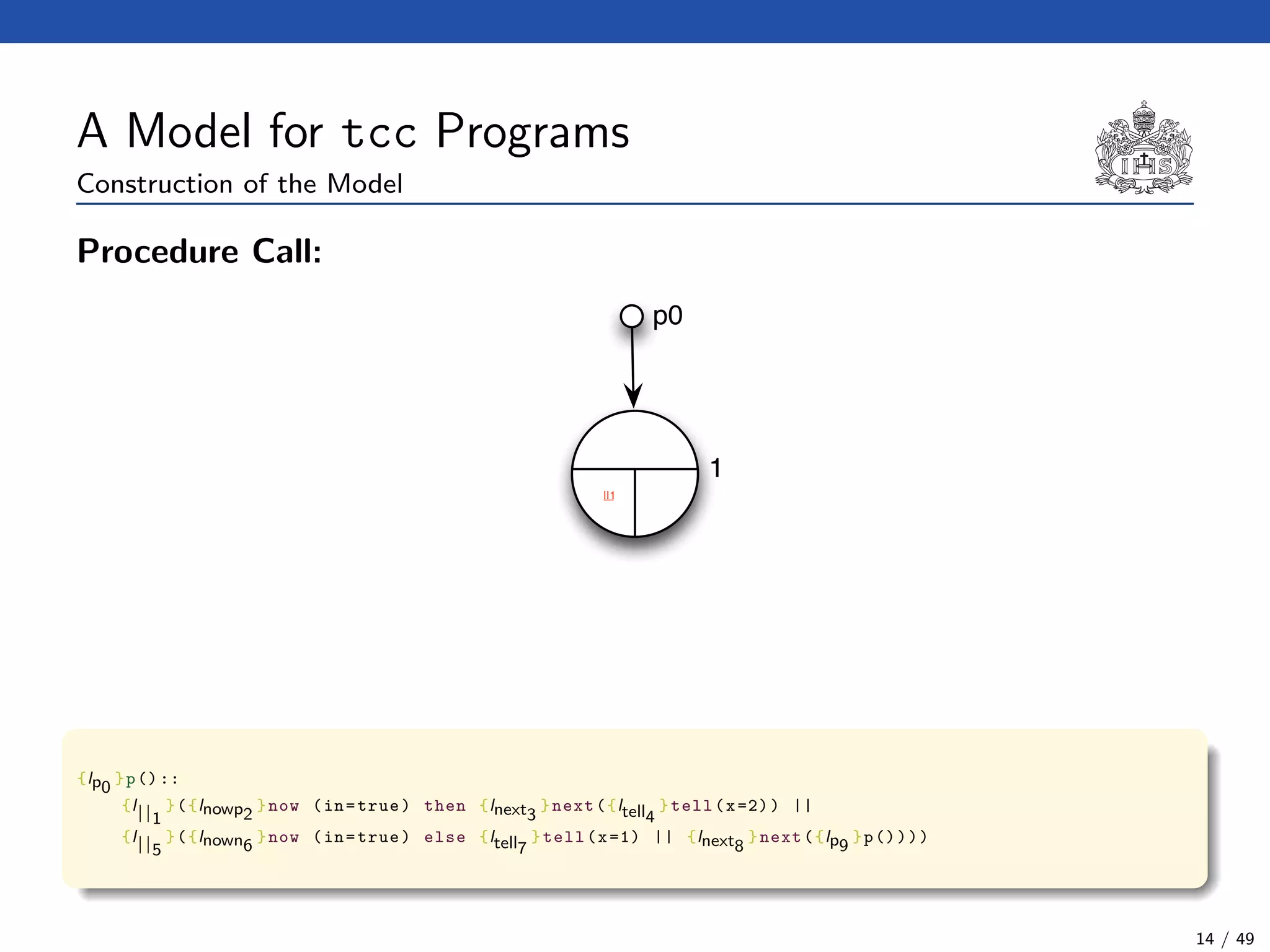

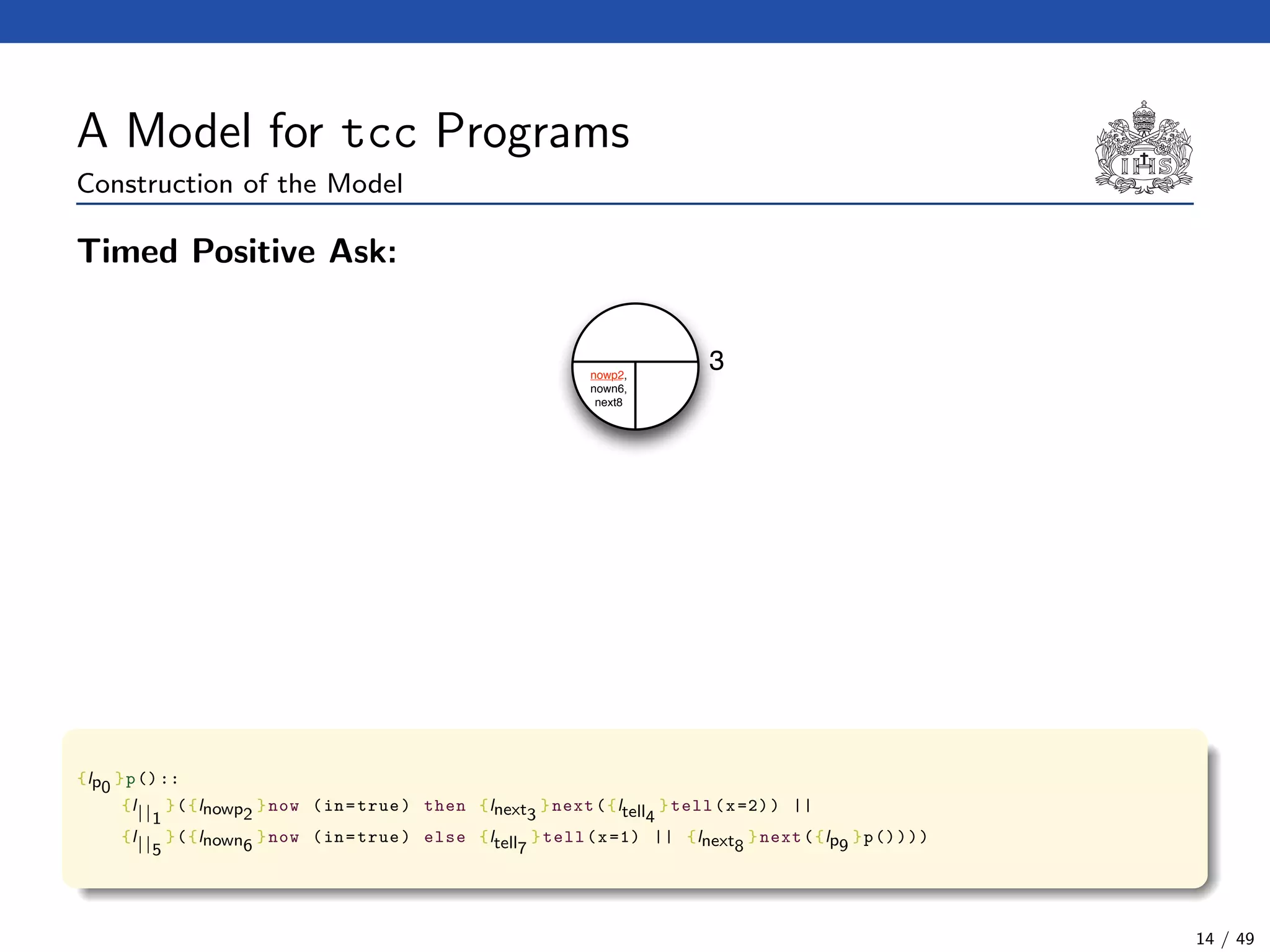

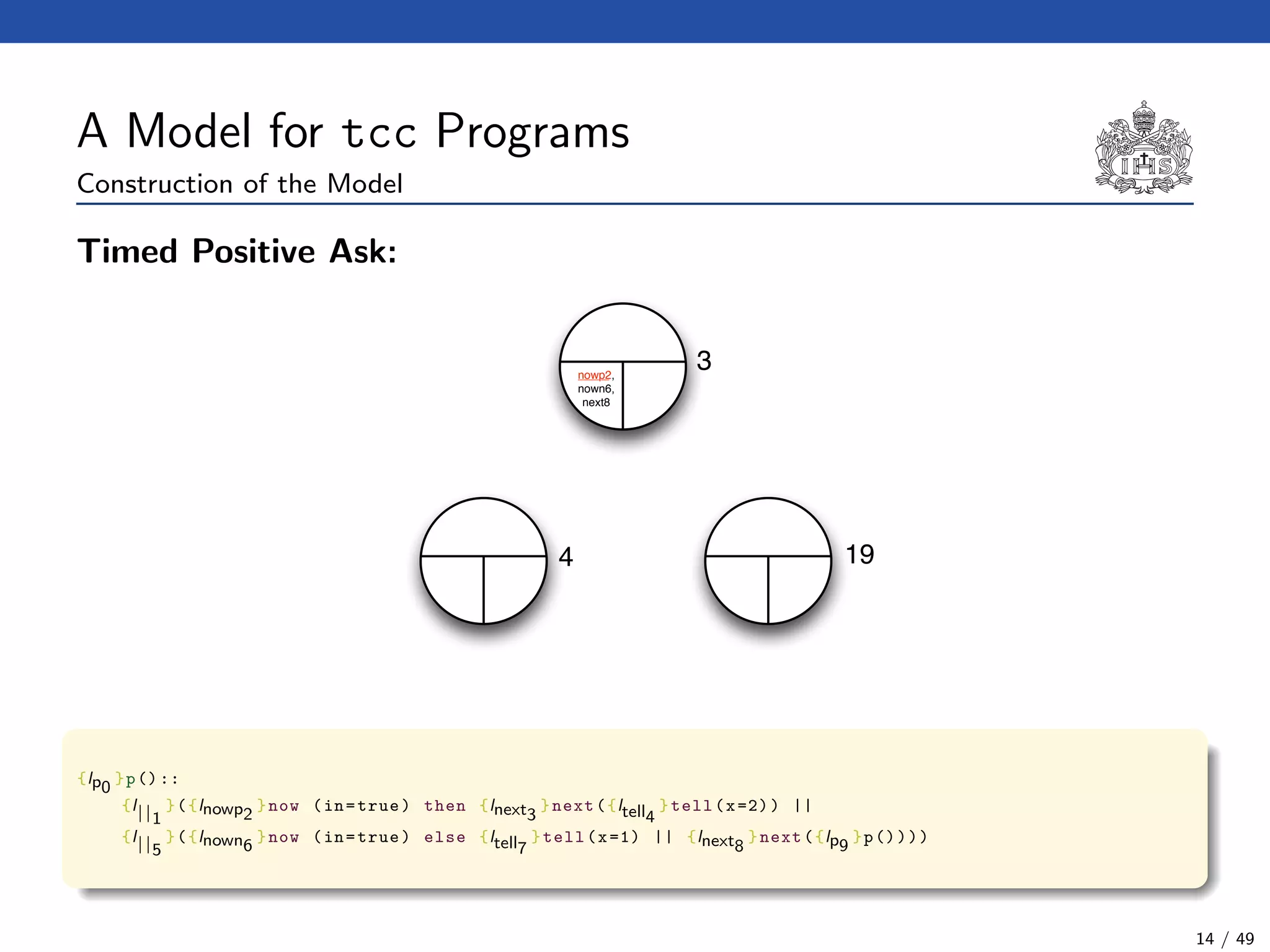

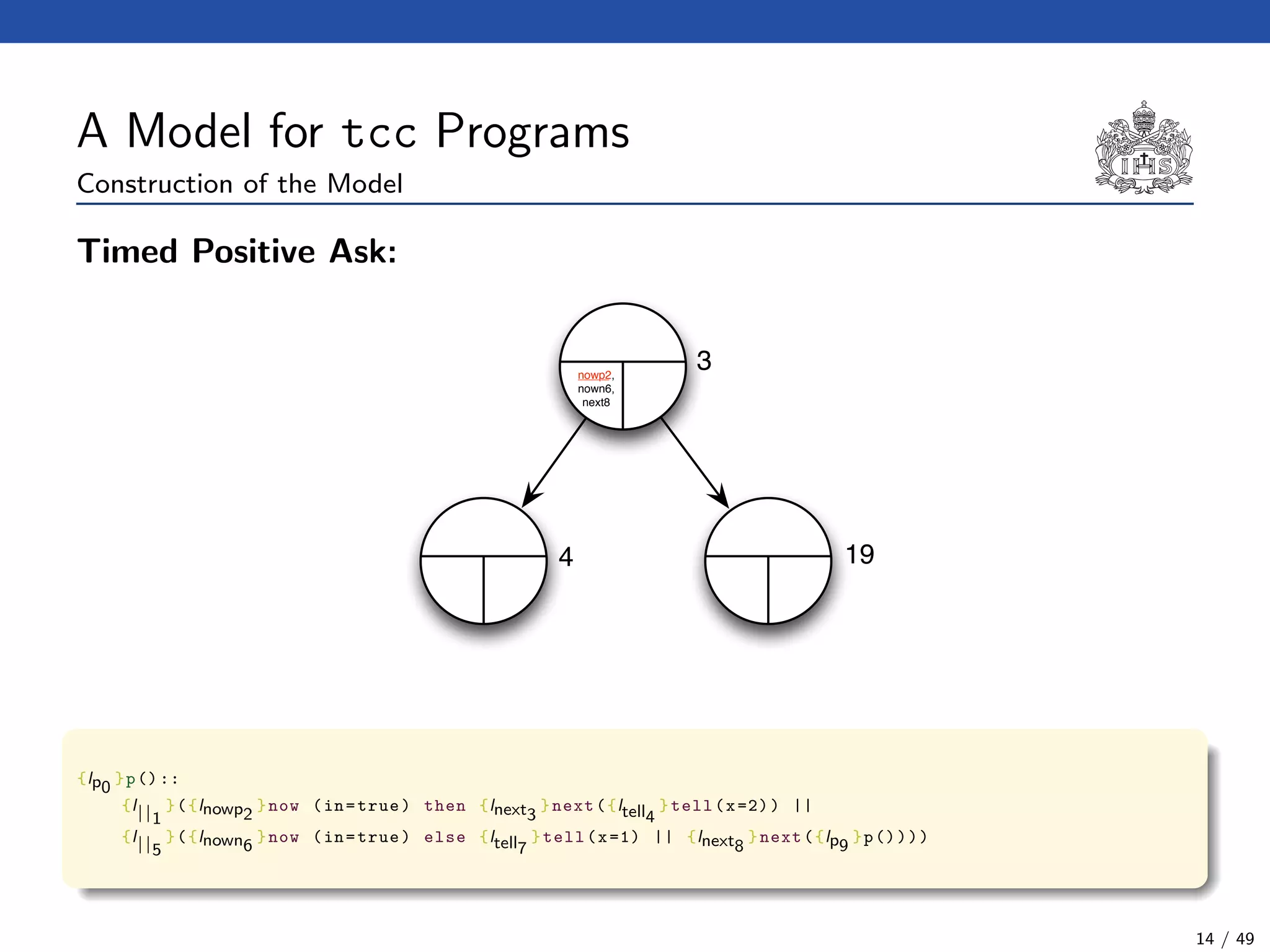

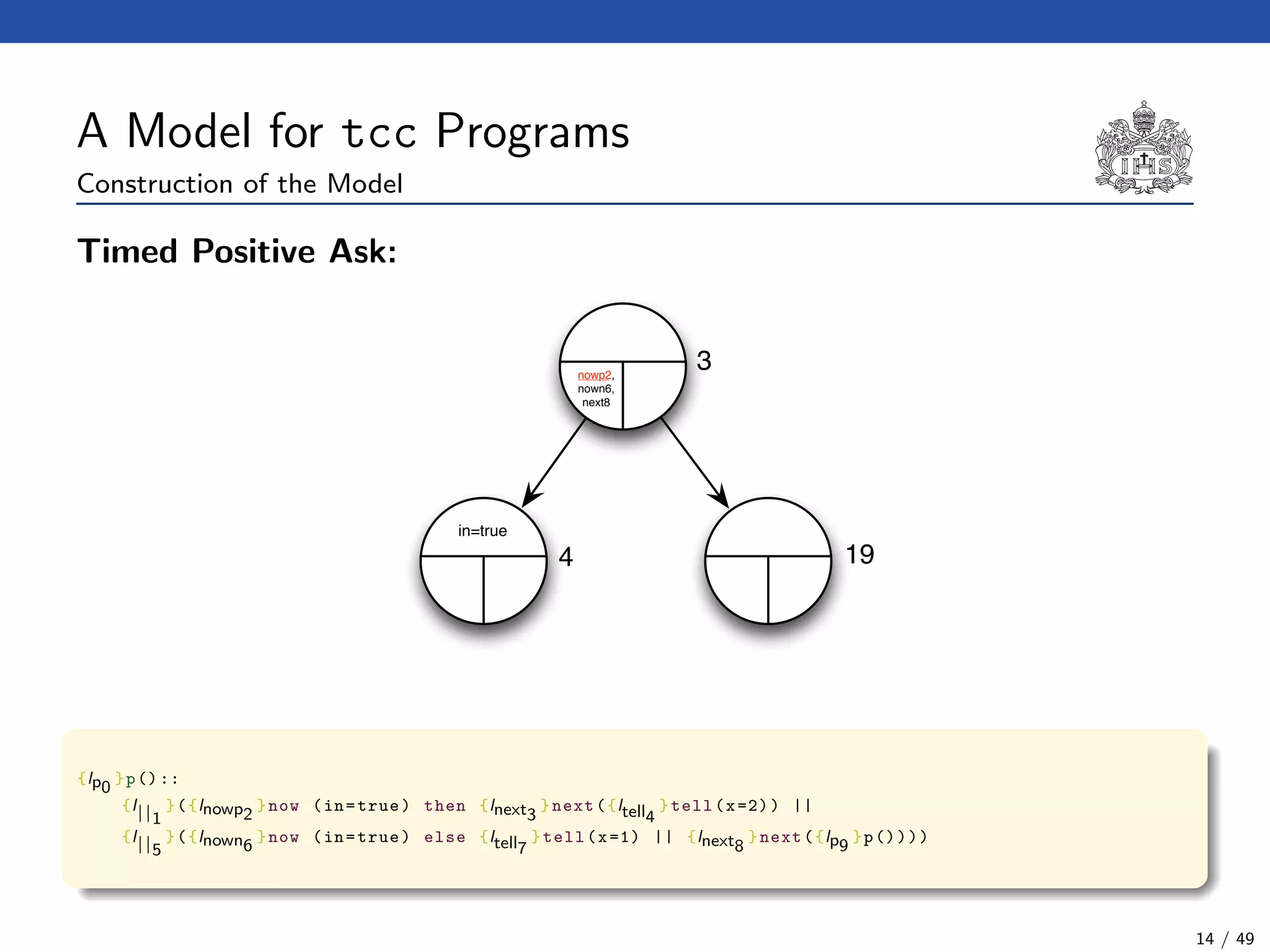

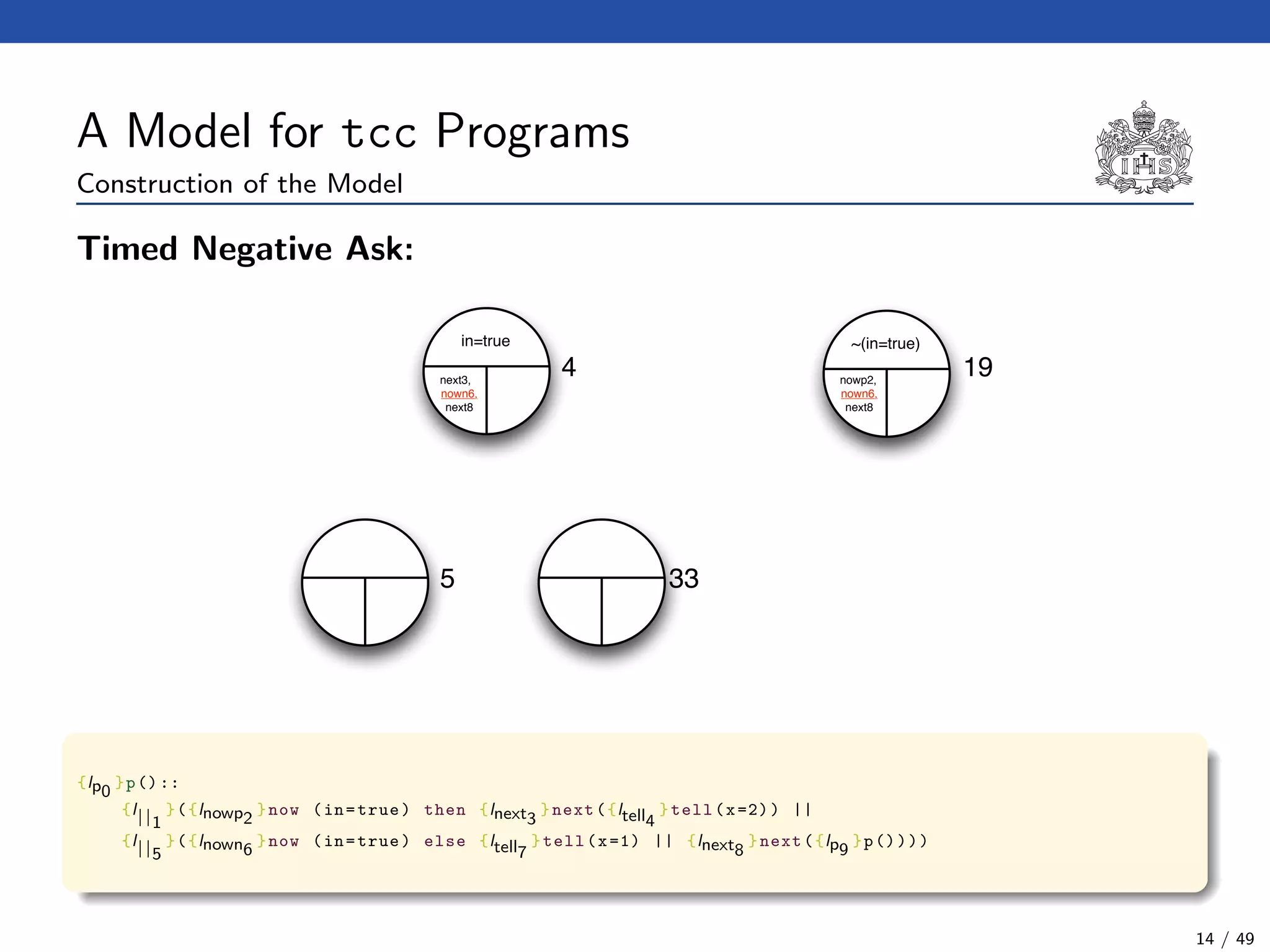

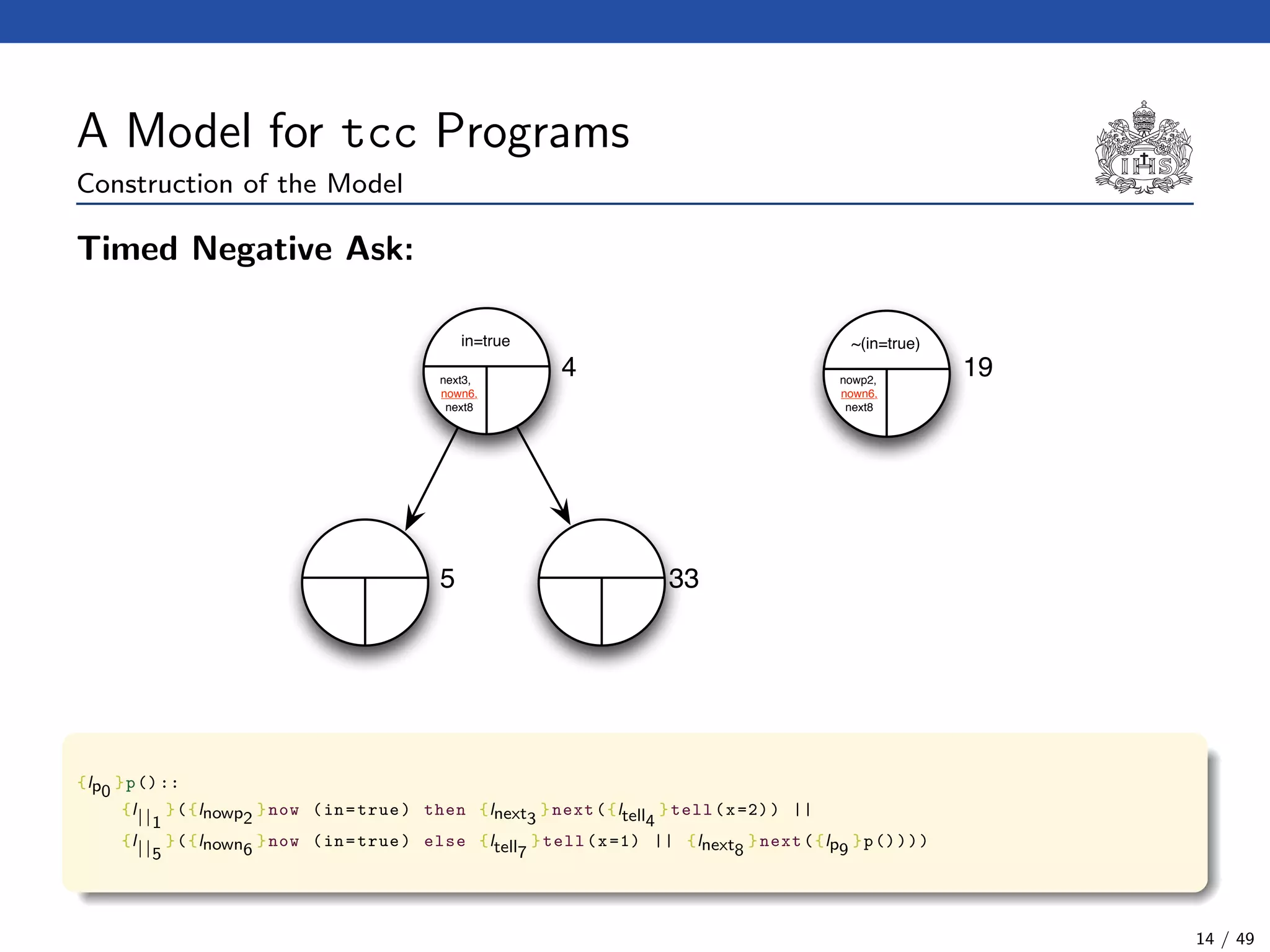

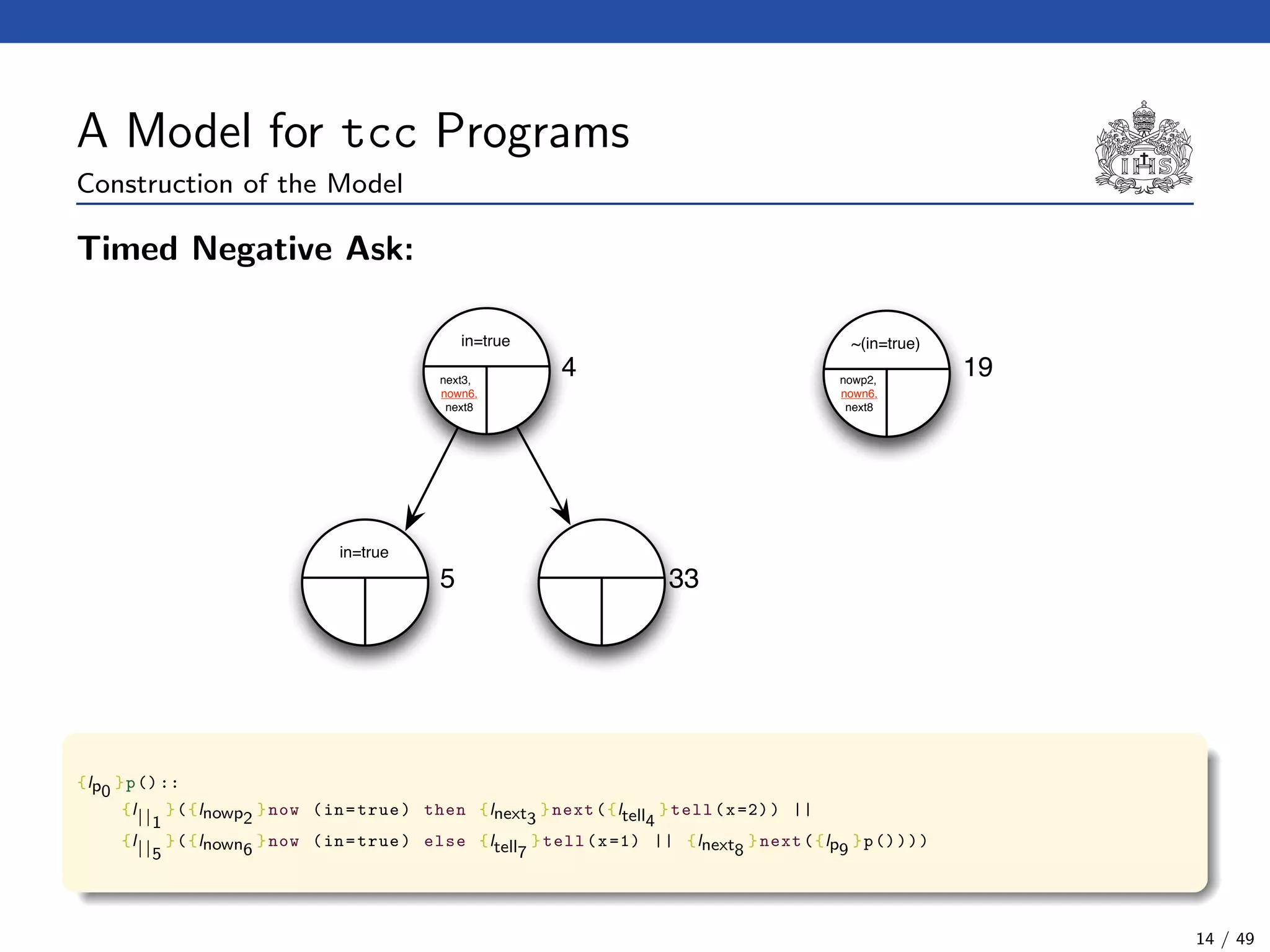

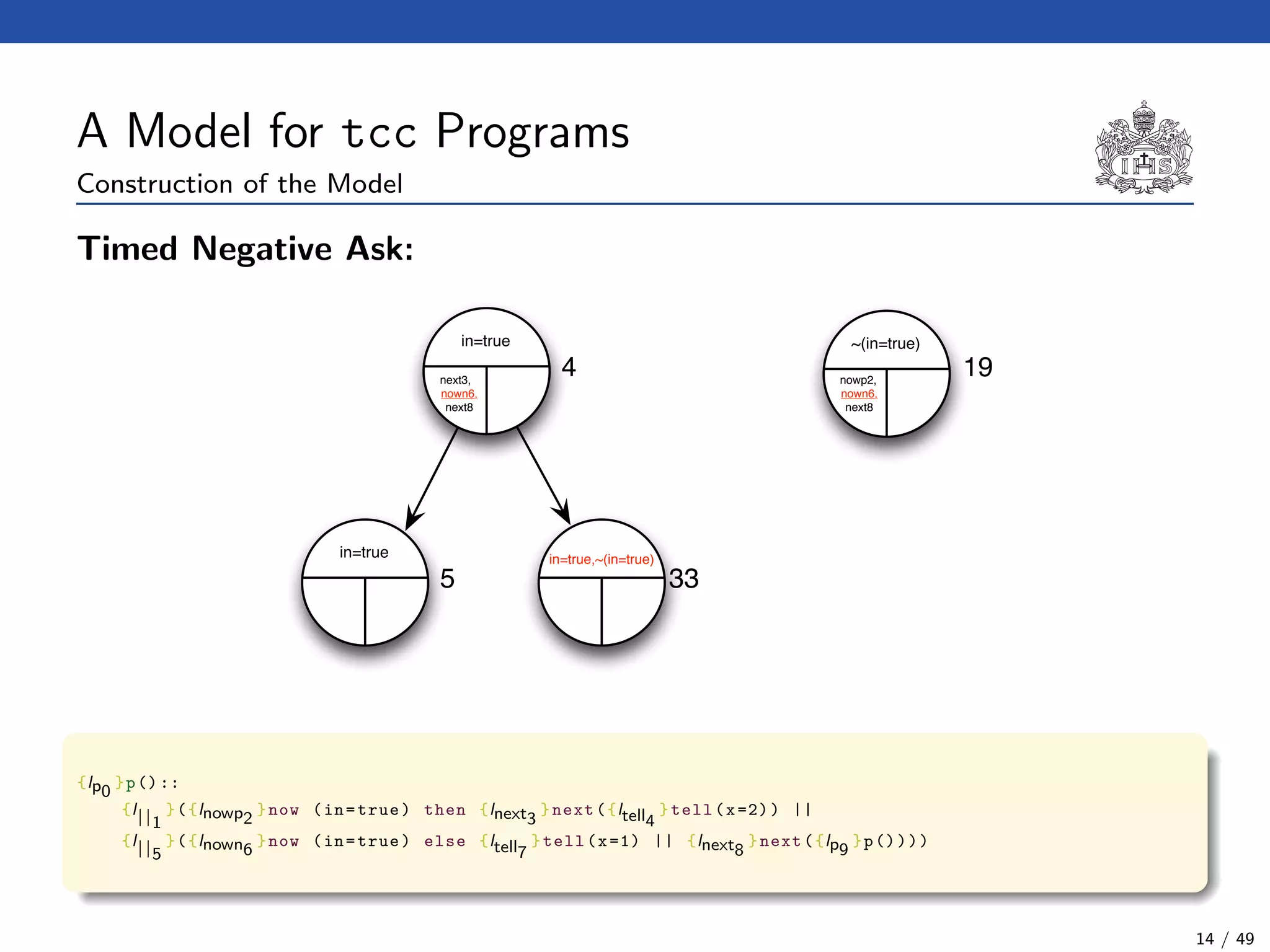

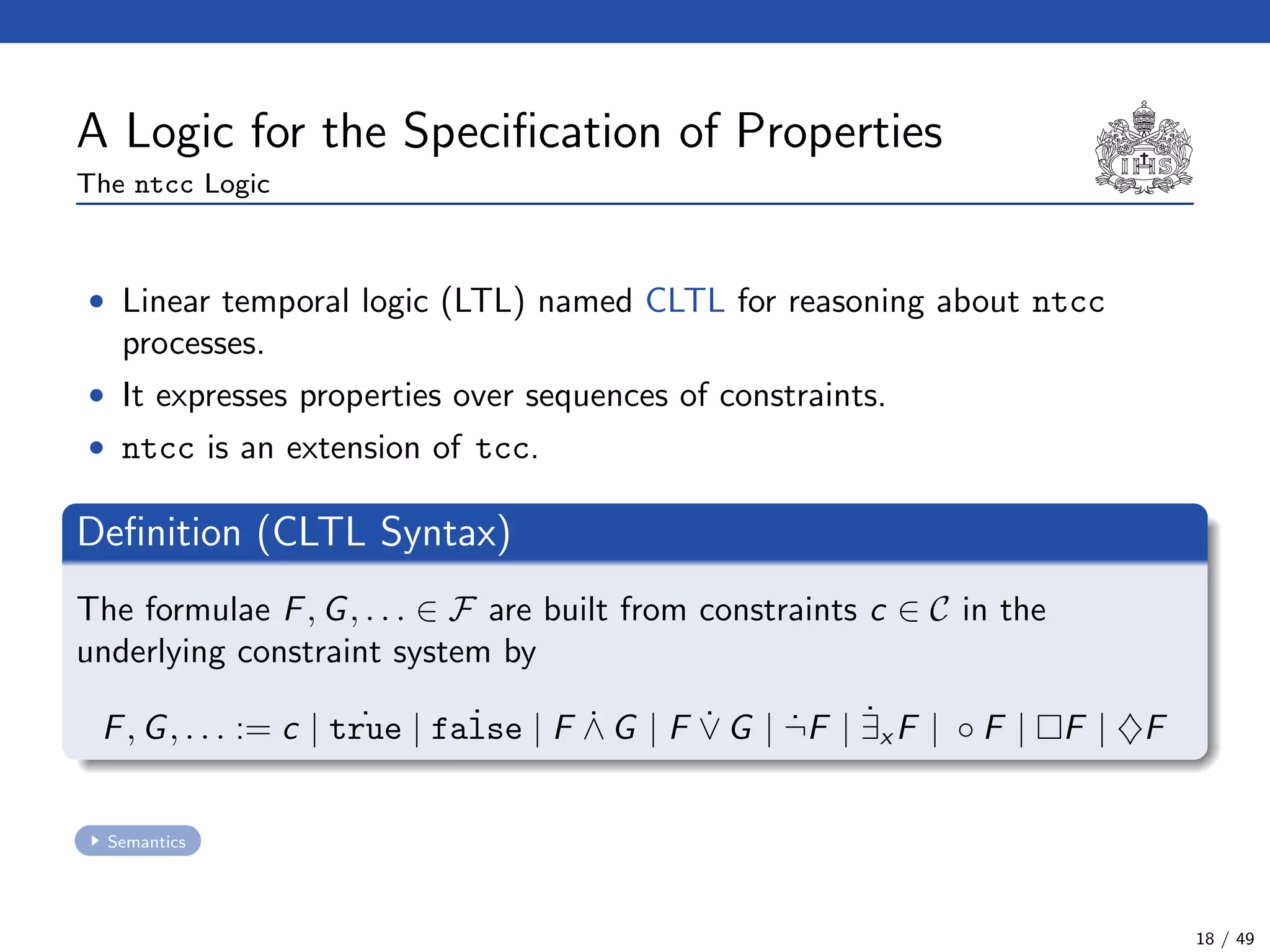

The document describes a model checking technique for the ntcc calculus. It involves constructing a tcc structure model from ntcc programs by labeling occurrences of agents. The tcc structure is a variant of a Kripke structure that models the behavior of ntcc specifications. Properties are formally specified using temporal logic. The model checking algorithm then checks if the tcc structure model satisfies the temporal logic properties.

![Motivation

• Verification of ntcc programs is performed using inductive techniques since

the model does not provide automatic formal verification tools.

• Problems:

◦ Difficult

◦ Error prone

◦ Experts are required.

• Hubert Garavel [Gar08]: “...The research agenda for theoretical concur-

rency should therefore address the design of efficient algorithms for trans-

lating and verifying formal specifications of concurrent systems”.

3 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-3-2048.jpg)

![Motivation

• Model checking is an automated technique that, given a finite-state model

of a system and a formal property, systematically checks whether this

property holds for (a given state in) that model [CGP99].

• Advantages

◦ Formal technique.

◦ Fully-automatic.

◦ Experts are not required.

◦ Counterexample.

• Drawback

◦ State-space explosion problem.

4 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-4-2048.jpg)

![Previous work

1. Given a ntcc process and a CLTL property, transform the process into a

B¨uchi automaton and the formula into a process [Val05].

8 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-8-2048.jpg)

![Previous work

1. Given a ntcc process and a CLTL property, transform the process into a

B¨uchi automaton and the formula into a process [Val05].

2. Given a tccp process, a temporal logic property and a number n of time

units, generate a kripke structure and verify if the property satisfy such

structure [FV06].

8 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-9-2048.jpg)

![Previous work

1. Given a ntcc process and a CLTL property, transform the process into a

B¨uchi automaton and the formula into a process [Val05].

2. Given a tccp process, a temporal logic property and a number n of time

units, generate a kripke structure and verify if the property satisfy such

structure [FV06].

3. Given a probabilistic ntcc process, a probabilistic CTL property and

sequence of n inputs (i.e., constraints), generate a discrete-time markov

chain, export the chain into PRISM model checker and verify the

property [TB09]. http://ntccrt.sourceforge.net

8 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-10-2048.jpg)

![Previous work

1. Given a ntcc process and a CLTL property, transform the process into a

B¨uchi automaton and the formula into a process [Val05].

2. Given a tccp process, a temporal logic property and a number n of time

units, generate a kripke structure and verify if the property satisfy such

structure [FV06].

3. Given a probabilistic ntcc process, a probabilistic CTL property and

sequence of n inputs (i.e., constraints), generate a discrete-time markov

chain, export the chain into PRISM model checker and verify the

property [TB09]. http://ntccrt.sourceforge.net

4. Given a ntcc process, a CLTL property and a number n of time units,

generate a finite-state automaton that represents the process and another

one that represents the property, then verify if the process satisfies the

formula [TB12]. http://ntccmc.sourceforge.net

8 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-11-2048.jpg)

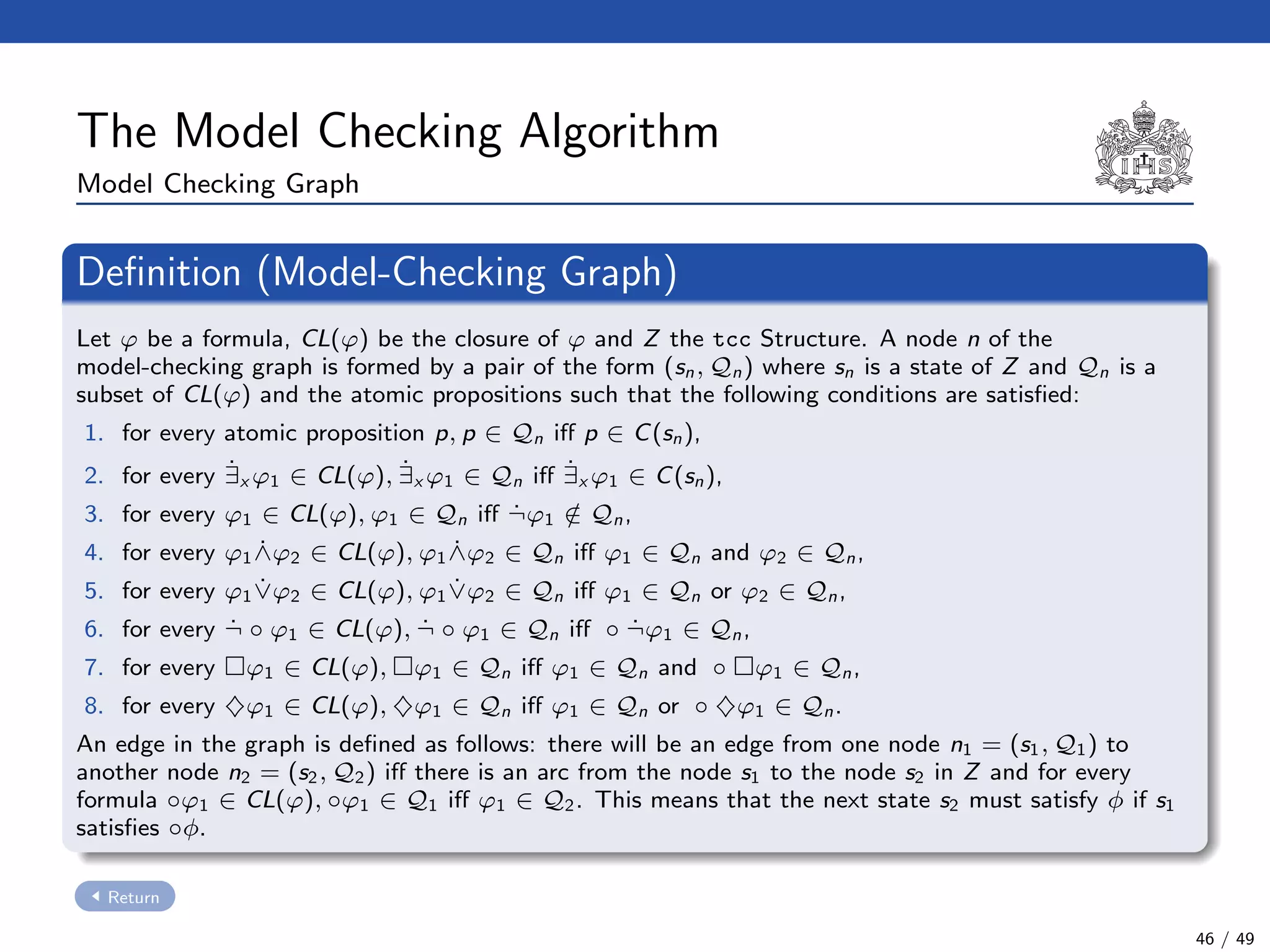

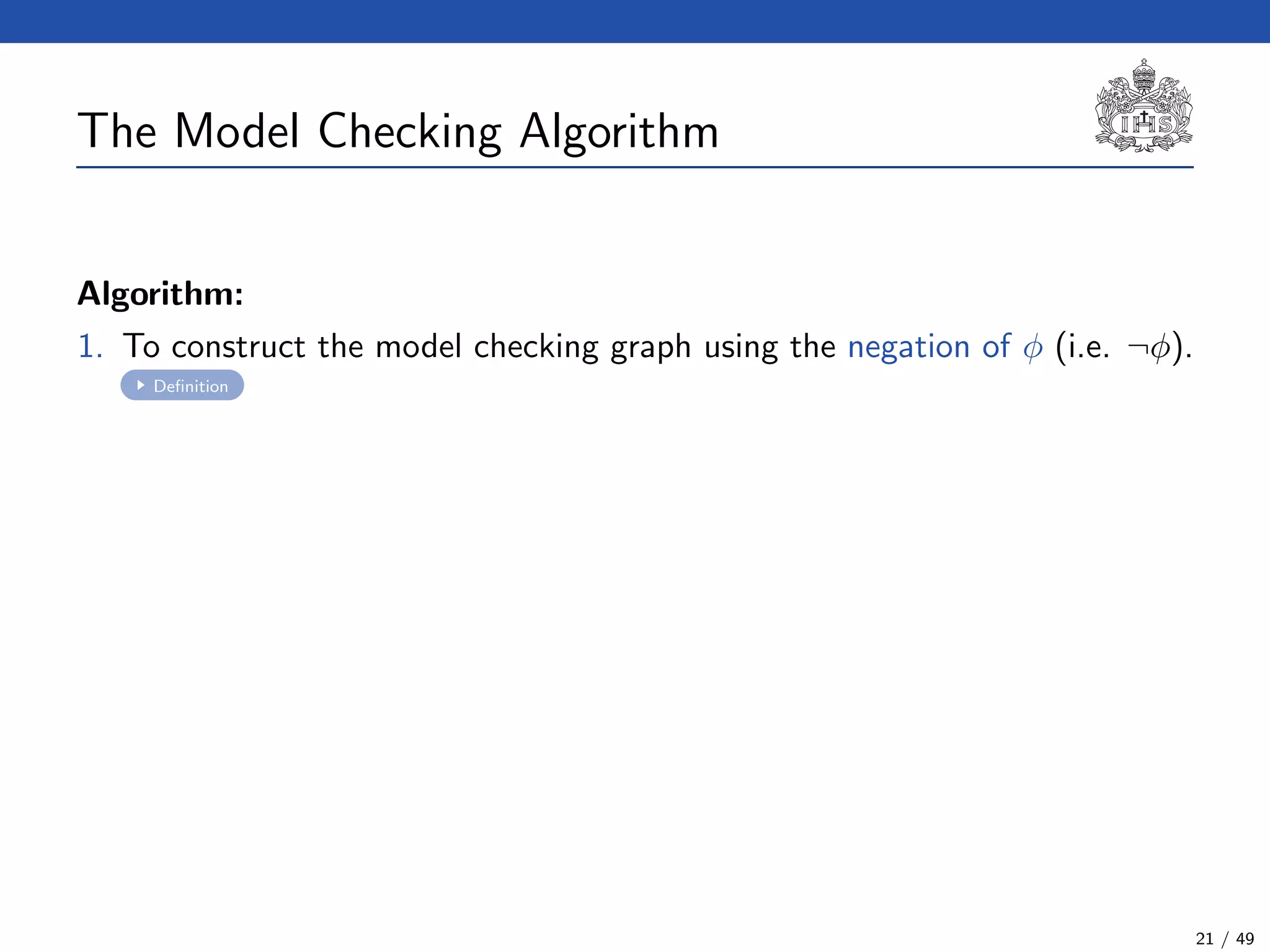

![The Model Checking Algorithm

• Classical tableau algorithm for the LTL model checking

problem [CGP99, MP95, LP85].

• To prove that a property is satisfied, it is possible to prove that there is no

path in the model checking graph satisfying the negation of the formula.

20 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-65-2048.jpg)

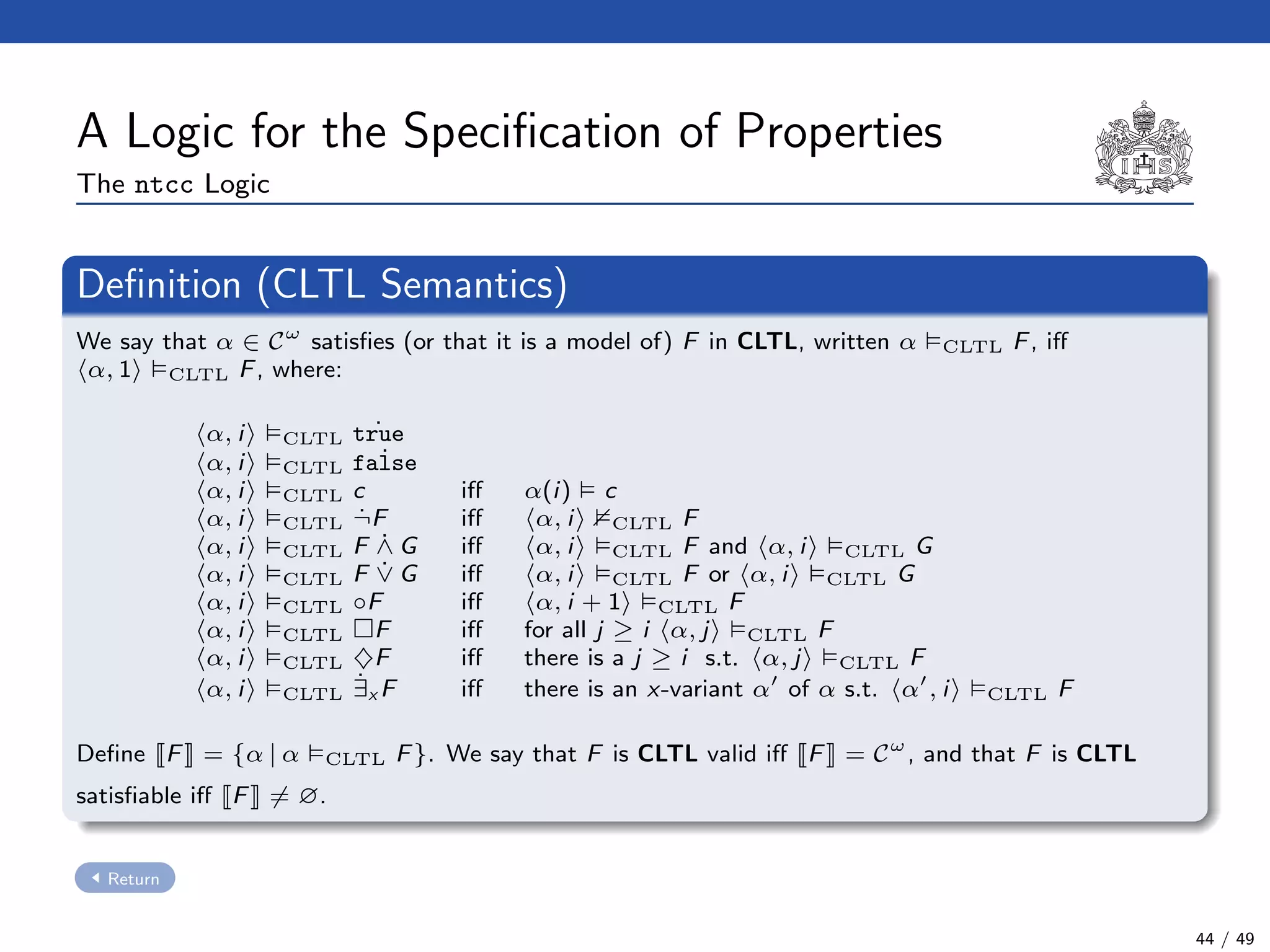

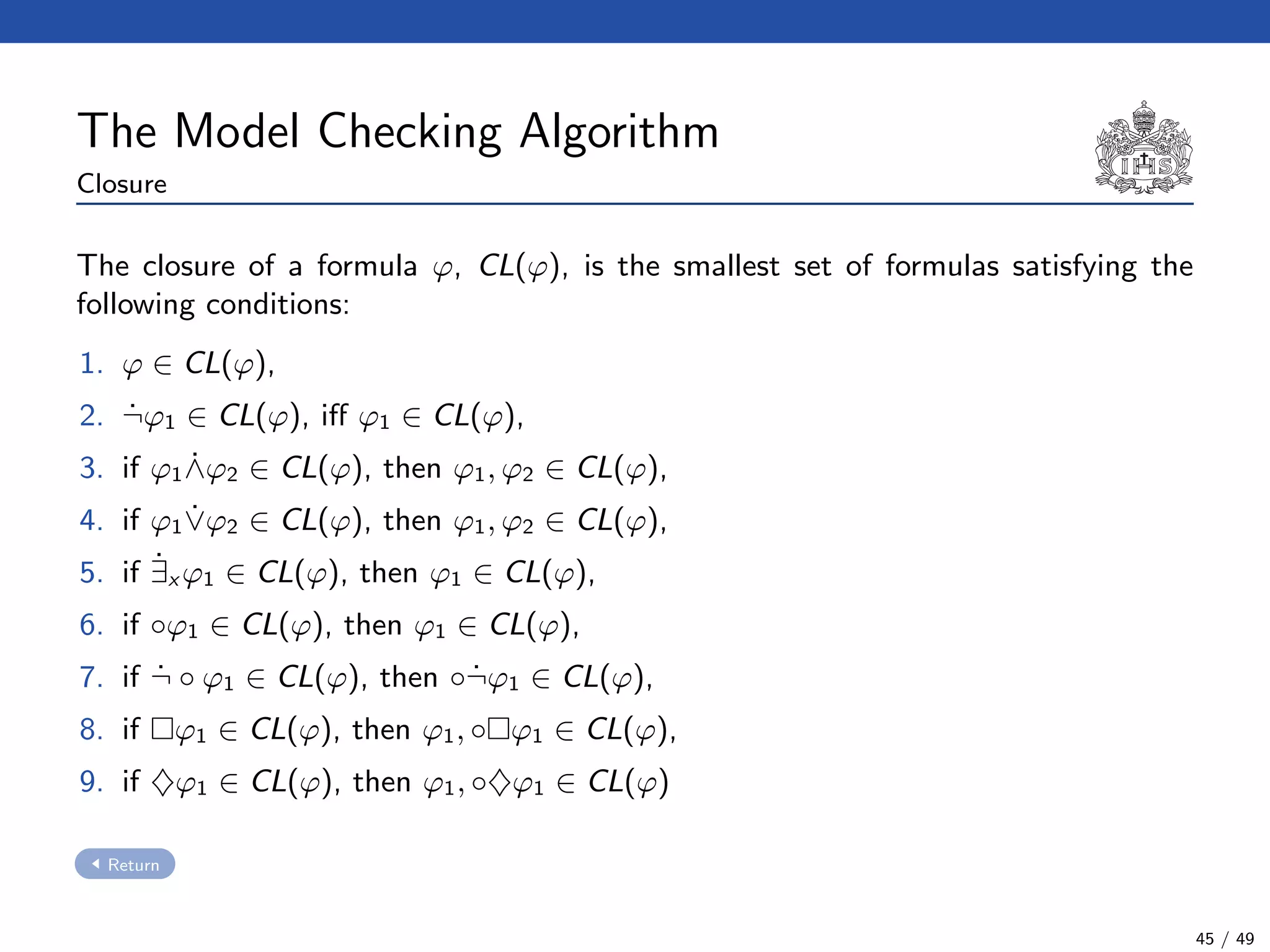

![The Model Checking Algorithm

Algorithm:

1. To construct the model checking graph using the negation of φ (i.e. ¬φ).

Definition

◦ First of all, we have to compute the closure CL(¬φ). This closure is

reminiscent to the Fisher Ladner’s one [MP95, FL79]. Definition

21 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-67-2048.jpg)

![The Model Checking Algorithm

Algorithm:

1. To construct the model checking graph using the negation of φ (i.e. ¬φ).

Definition

◦ First of all, we have to compute the closure CL(¬φ). This closure is

reminiscent to the Fisher Ladner’s one [MP95, FL79]. Definition

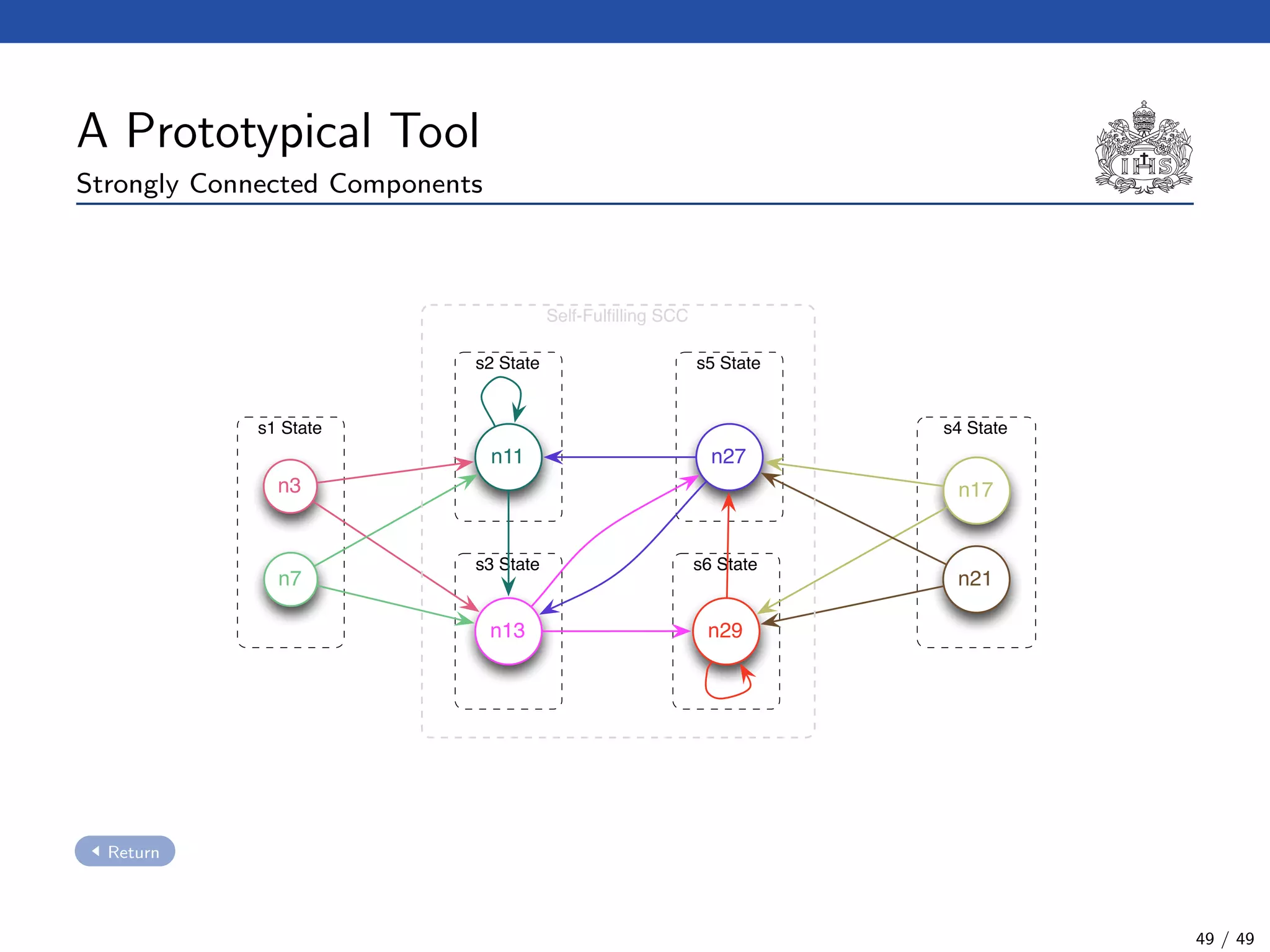

2. To look for a sequence such that starting from an initial node of the

graph that satisfies the negation of φ, it reaches a self-fulfilling strongly

connected component.

21 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-68-2048.jpg)

![The Model Checking Algorithm

Algorithm:

1. To construct the model checking graph using the negation of φ (i.e. ¬φ).

Definition

◦ First of all, we have to compute the closure CL(¬φ). This closure is

reminiscent to the Fisher Ladner’s one [MP95, FL79]. Definition

2. To look for a sequence such that starting from an initial node of the

graph that satisfies the negation of φ, it reaches a self-fulfilling strongly

connected component.

3. If we find a self-fulfilling SCC in the graph, then the system satisfies the

property represented by the negated formula (i.e. the model does not

satisfy the property).

21 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-69-2048.jpg)

![The tcc Calculus [SJG94]

Formal Syntax

(Agents) A ::= c (Tell)

| now c then A (Timed Positive Ask)

| now c else A (Timed Negative Ask)

| next A (Unit Delay)

| abort (Abort)

| skip (Skip)

| A || A (Parallel Composition)

| ∃x(A) (Hiding)

| g (Procedure Call)

(Procedure Calls) g ::= p(t1, . . . , tn)

(Declarations) D ::= g :: A (Definition)

| D.D (Conjunction)

(Programs) P ::= D.A

Return

32 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-85-2048.jpg)

![The tcc Calculus [SJG94]

Formal Operational Semantics

Axioms for →. The binary relation → on configurations is the least relation satisfying the

rules :

(?, skip) → ?

(?, abort) → abort

(?, A || B) → (?, A, B)

(?, ∃x(A)) → (?, A[y/x]) (y not free in ?)

(?, p(t1, . . . , tn)) → (?, A[x1 → t1, . . . , xn → tn])

σ(?) c

(?, now c then A) → (?, A)

σ(?) c

(?, now c else B) → ?

Axioms for . The binary relation is the least relation satisfying the single rule :

∆, {now ci else Ai | i < n}

∆, {now ci else Ai | i < n}, {next Bj | j < m} {Ai | i < n}, {Bj | j < m}

Return

33 / 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-avispa-february-2013-180901185216/75/Model-checker-for-NTCC-86-2048.jpg)