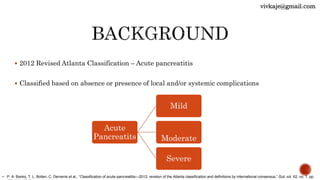

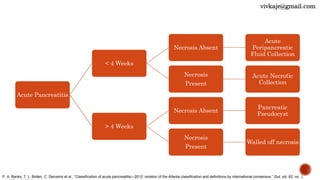

The document discusses the classification and treatment of acute pancreatitis. It classifies pancreatitis based on the absence or presence of local and systemic complications into mild, moderate, or severe. For infected pancreatic collections or necrosis that develop after the initial presentation, the document recommends initially performing simple percutaneous drainage and then considering minimally invasive techniques like endoscopic or laparoscopic necrosectomy if the patient does not improve with drainage alone. It notes that no single technique is clearly superior and treatment should be individualized based on the patient and collection characteristics.