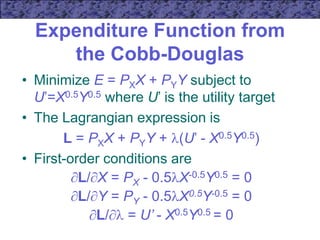

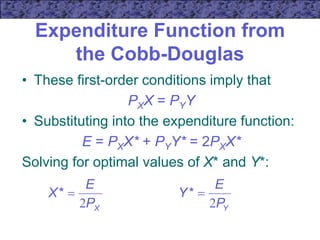

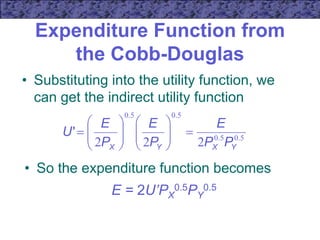

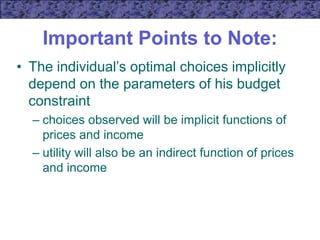

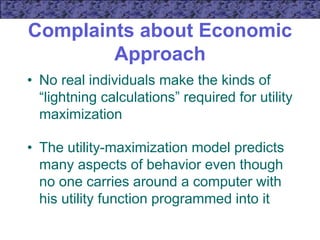

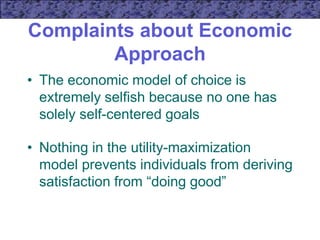

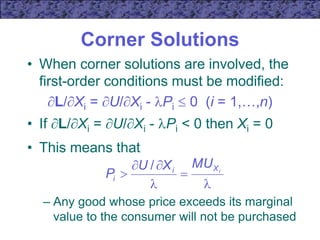

1) The document discusses the economic model of utility maximization and choice under budget constraints. It outlines some complaints about the model but also notes the model predicts behavior even without individuals consciously carrying out calculations.

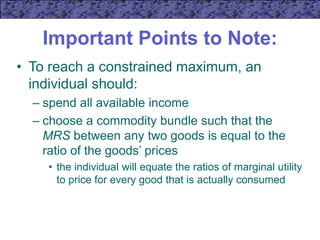

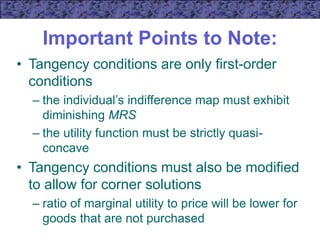

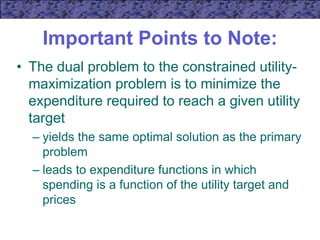

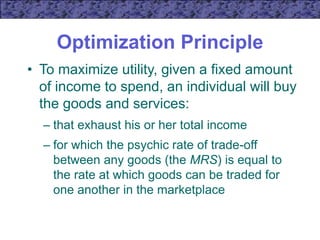

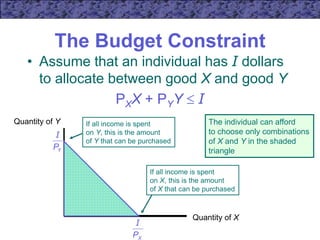

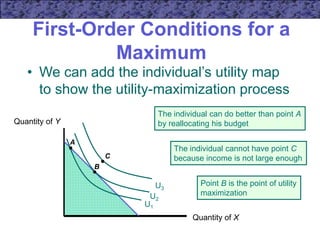

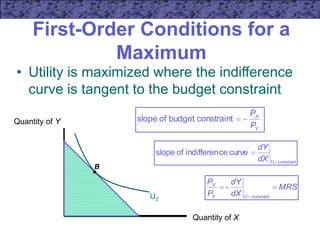

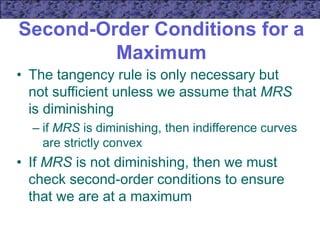

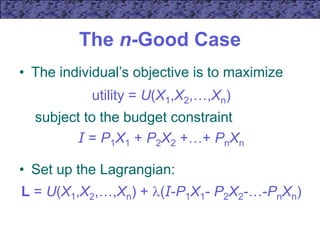

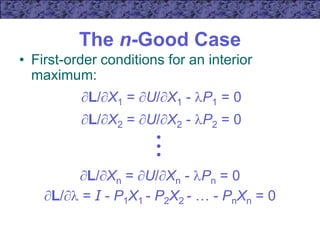

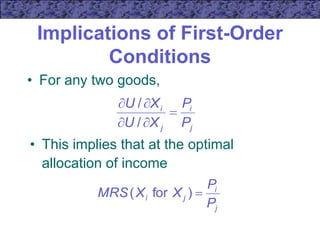

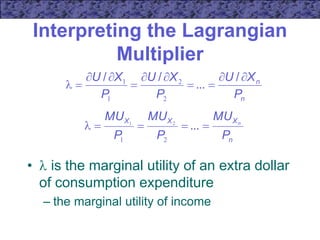

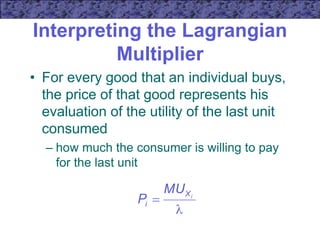

2) It explains that for a consumer to maximize utility, they will spend all their income and choose a bundle where the marginal rate of substitution between any two goods equals the price ratio between those goods.

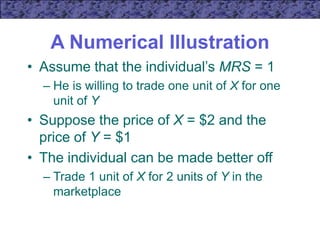

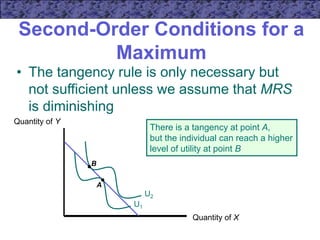

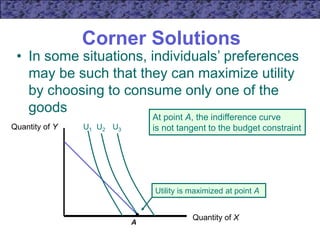

3) A numerical example illustrates this principle using indifference curves and budget constraints. The consumer maximizes utility at the point of tangency between the indifference curve and budget line.

![Cobb-Douglas Demand

Functions

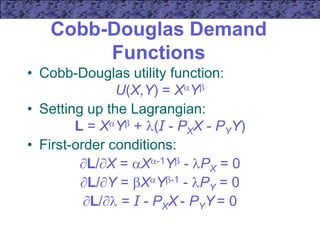

• First-order conditions imply:

Y/X = PX/PY

• Since + = 1:

PYY = (/)PXX = [(1- )/]PXX

• Substituting into the budget constraint:

I = PXX + [(1- )/]PXX = (1/)PXX](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecn5402-220908092307-d2b4197e/85/MICROECONOMIC-THEORY-19-320.jpg)

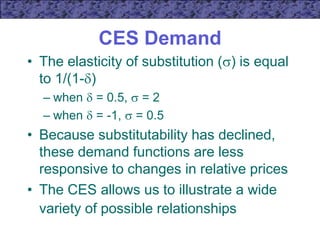

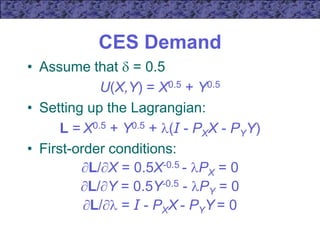

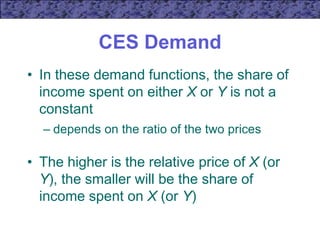

![CES Demand

• This means that

(Y/X)0.5 = Px/PY

• Substituting into the budget constraint,

we can solve for the demand functions:

]

1

[

*

Y

X

X

P

P

P

X

I

]

1

[

*

X

Y

Y

P

P

P

Y

I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecn5402-220908092307-d2b4197e/85/MICROECONOMIC-THEORY-23-320.jpg)

![CES Demand

• If = -1,

U(X,Y) = X-1 + Y-1

• First-order conditions imply that

Y/X = (PX/PY)0.5

• The demand functions are

]

1

[

* 5

.

0

X

Y

X

P

P

P

X

I

]

1

[

* 5

.

0

Y

X

Y

P

P

P

Y

I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecn5402-220908092307-d2b4197e/85/MICROECONOMIC-THEORY-25-320.jpg)