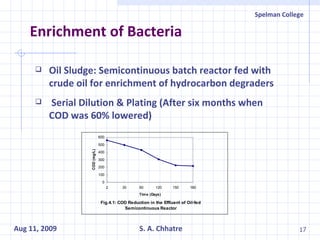

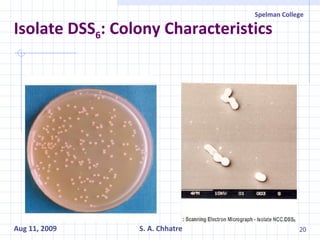

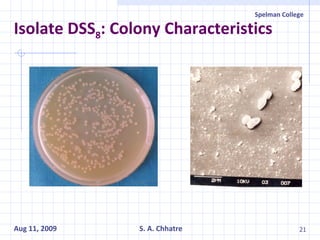

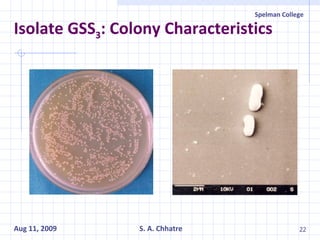

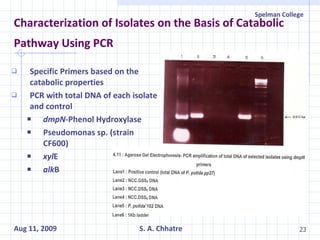

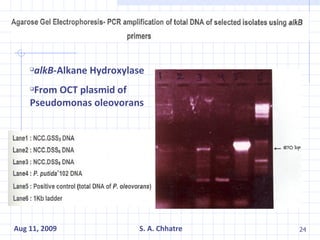

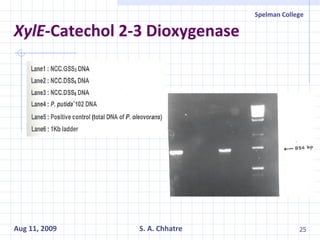

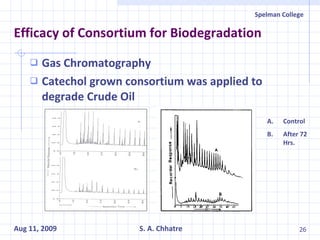

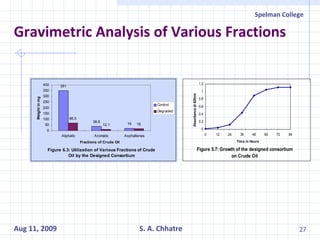

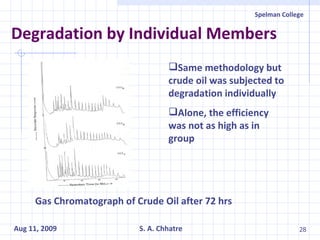

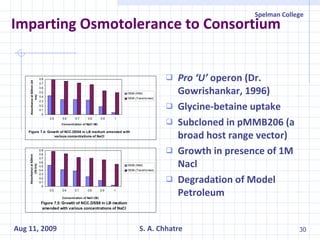

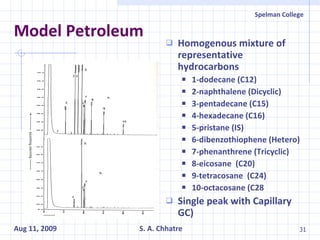

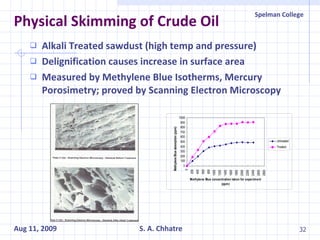

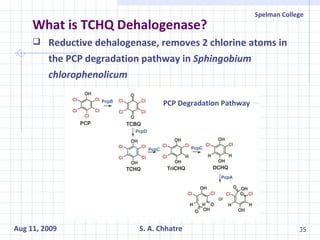

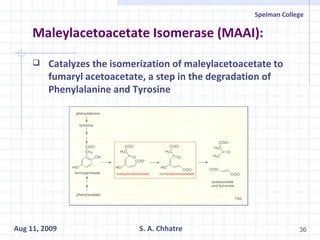

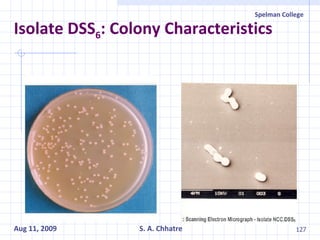

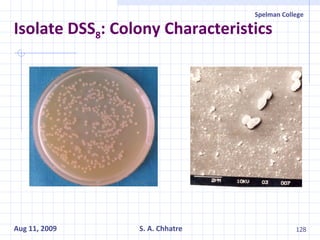

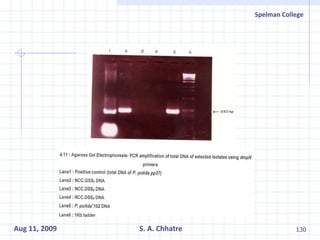

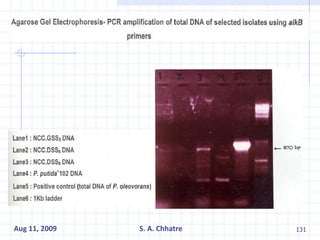

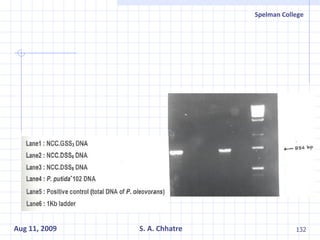

The document summarizes research on exploring microbial diversity to identify novel microbial functions. It describes enrichment and isolation of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria from oil sludge to create a bacterial consortium for bioremediating oil spills. Molecular tools were used to characterize the isolates and determine their catabolic pathways. The consortium showed improved degradation of crude oil and model petroleum compounds compared to individual isolates.