This document summarizes the research goals and findings of developing an intelligent design assistant for memory synthesis using AI methods. It discusses the growing performance gap between processors and main memory, and how memory hierarchy addresses this by organizing memory into faster, smaller, more expensive levels. The document outlines the knowledge acquisition and domain knowledge required for the memory synthesis tool, including topics like cache organization, memory protocols, consistency models, and optimizing overall memory system design.

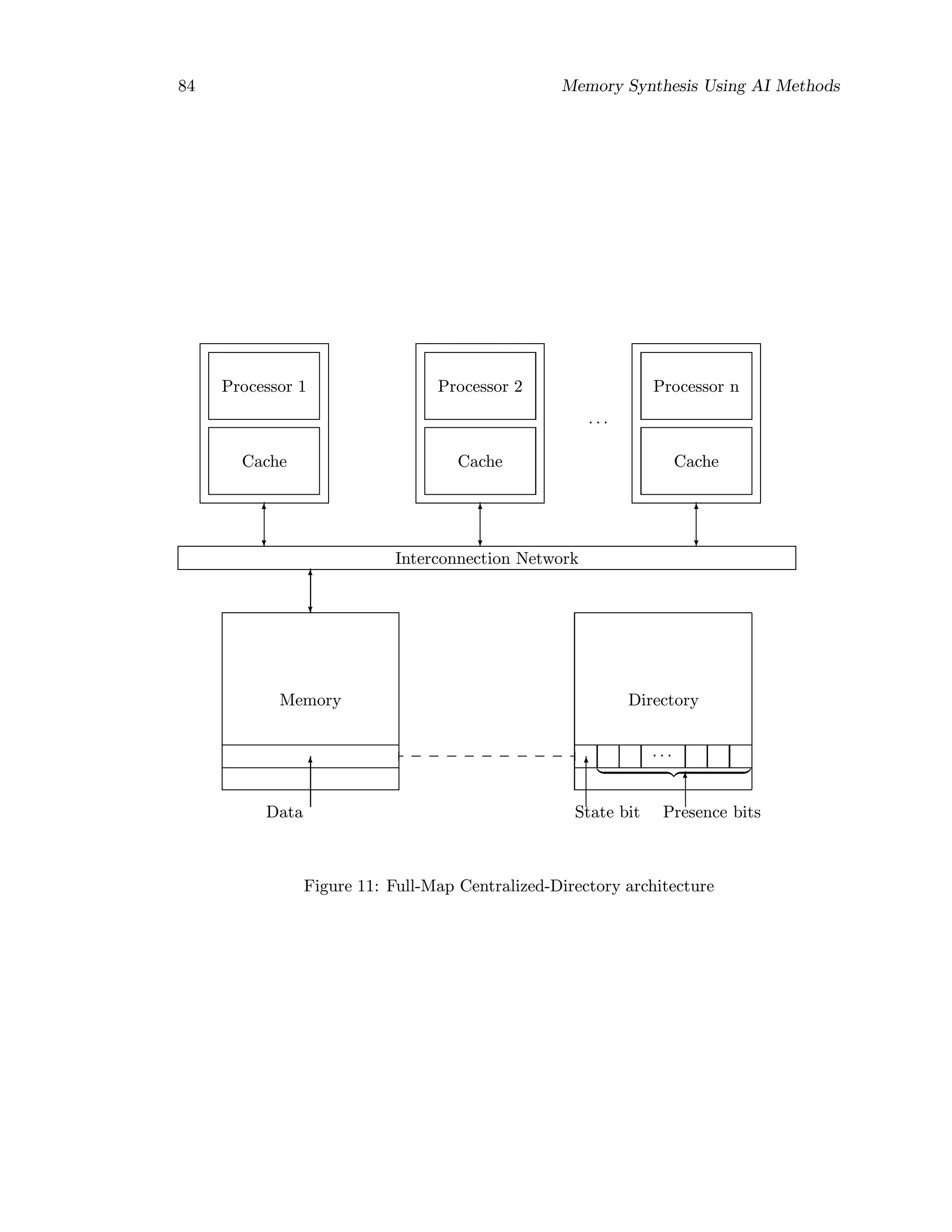

![12 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

4 COMPUTER ARCHITECTURE OVERVIEW

4.1 An Architecure Classification

Designing a computer system is a task having many aspects, including instruction set de-

sign, functional organization, logic design, and implementation. The design of the machine

should be optimized across these levels. The term instruction set architecture refers to the

actual programmer-visible instruction set. The instruction set architecture serves as the

boundary between the hardware and the software. The term organization includes the

high-level aspects of a computer’s design, such as the memory system, the bus structure,

and the internal CPU design. Hardware is used to refer to the specifics of a machine, such

as the detailed logic design and the packaging technology of the machine. Hardware is

actually the main aspect of implementation, which encompasses integrated circuit design,

packaging, power, and cooling. We shall use the term architecture to cover all three aspects

of computer design.

According to the number of processors included, computer systems fall into two broad

categories: uniprocessor computers —which contain only one CPU—, and multiprocessor

computers —which contain more CPU’s. The CPU can be partitioned into into three

functional units, the instruction unit (also called the control unit) (I-unit), the execution

unit (E-unit), and the storage unit (S-unit);

• the I-unit is responsible for instruction fetch and decode and generates the control

signals; it may contain some local buffers for instruction prefetch (lookahead);

• the E-unit executes the instructions and contains the logic for arithmetic and logical

operations (the data path blocks);

• the S-unit provides the memory interface between the I-unit and the E-unit; it

provides memory management (protection, virtual address translation) and may

contain some additional components whose goal is to reduce the access time to data.

A finer classification of computer architectures may be made taking into account not only

the number of CPU’s but also the instruction and data flow. Under this approach, there

are three architectures ([7]):

• Single Instruction Stream Single Data Stream (SISD) architecture, in which a single

instruction stream is executed on a single stream of operands;

• Single Instruction Stream Multiple Data Stream (SIMD) architecture, in which a

single instruction stream is executed on several streams of operands;

• Multiple Instruction Stream Multiple Data Stream (MIMD) architecture, in which

different instruction streams are executed on different operand streams in parallel.

In this report we shall use as synonym for the MIMD architecture the term multiprocessor.

Multiprocesing is a way to increase system computing power. A distinctive feature of an](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-18-2048.jpg)

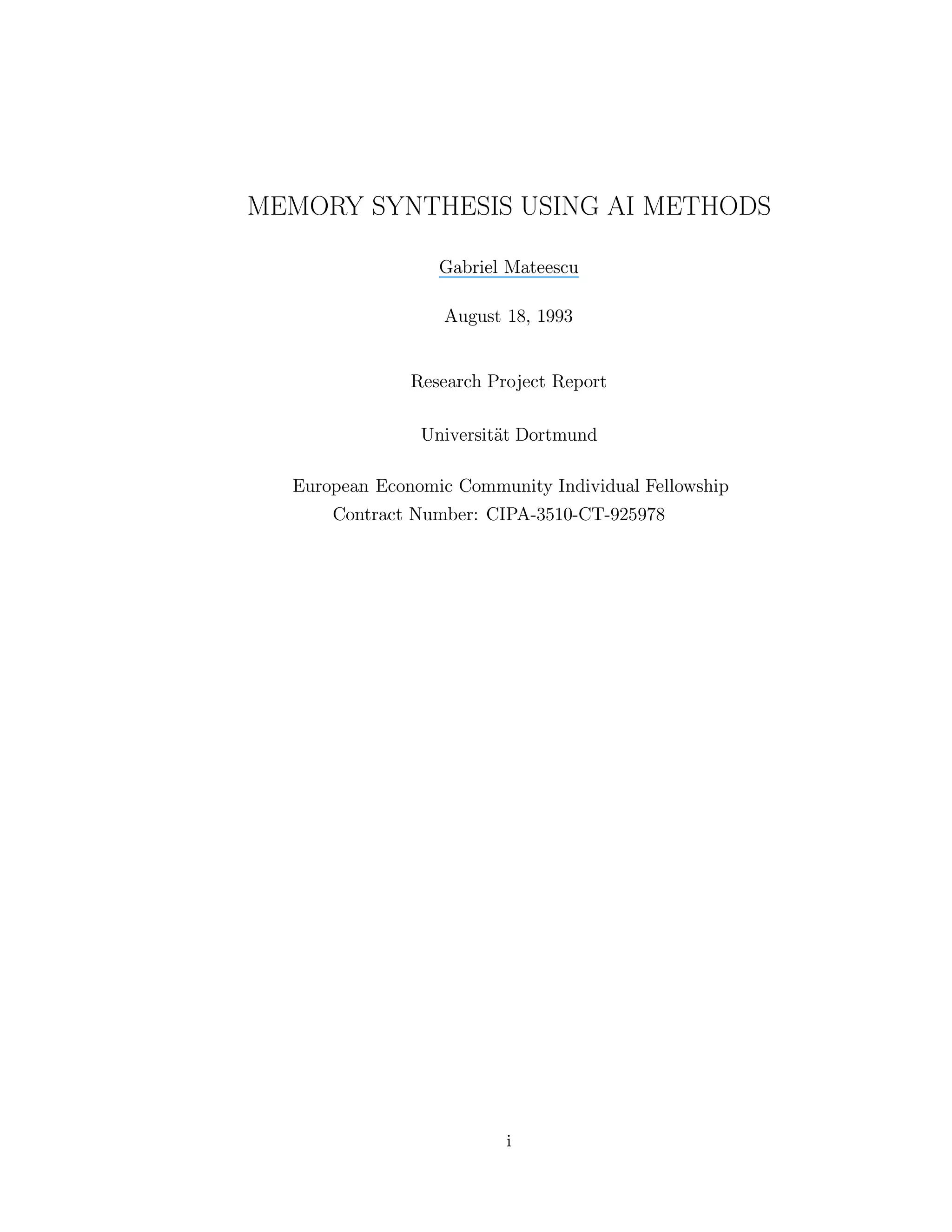

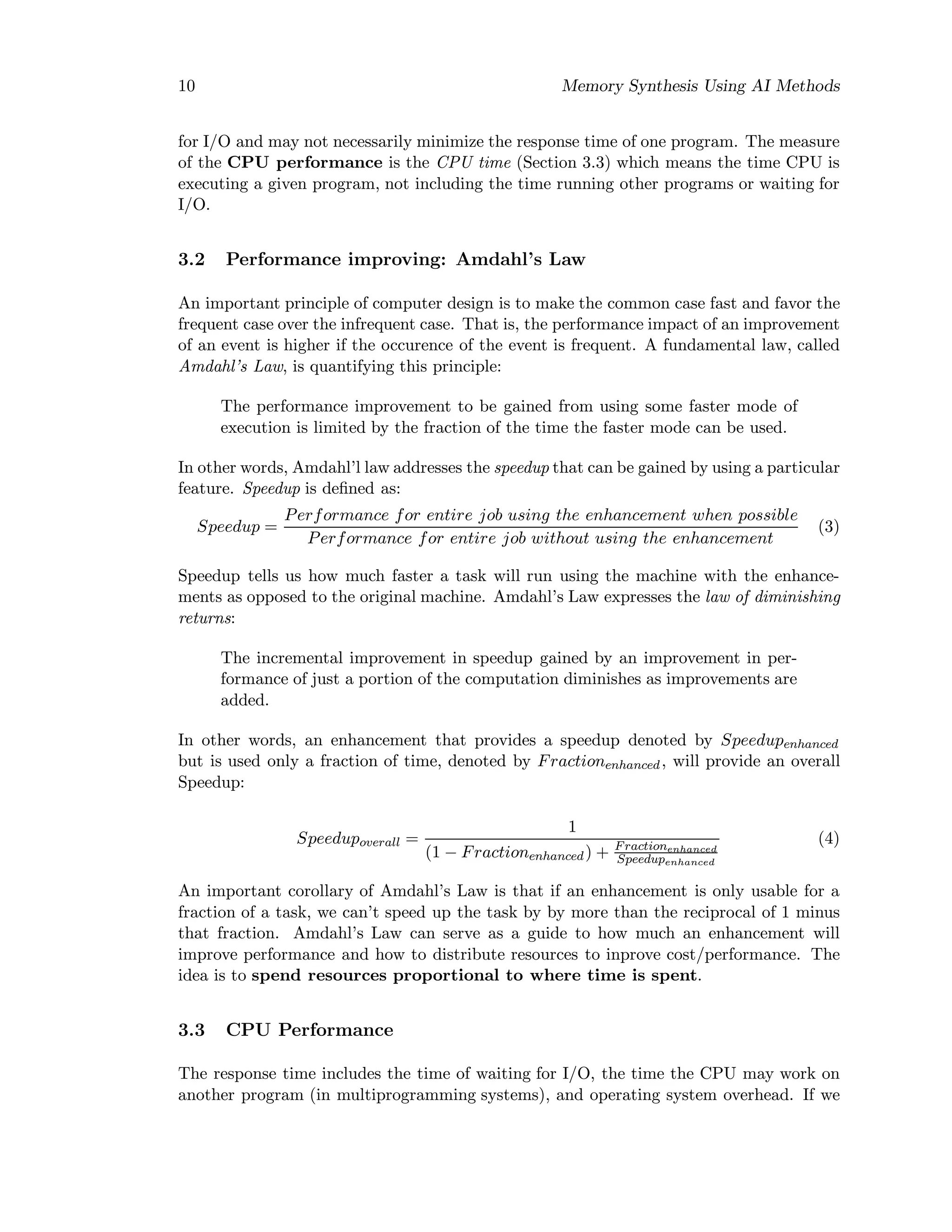

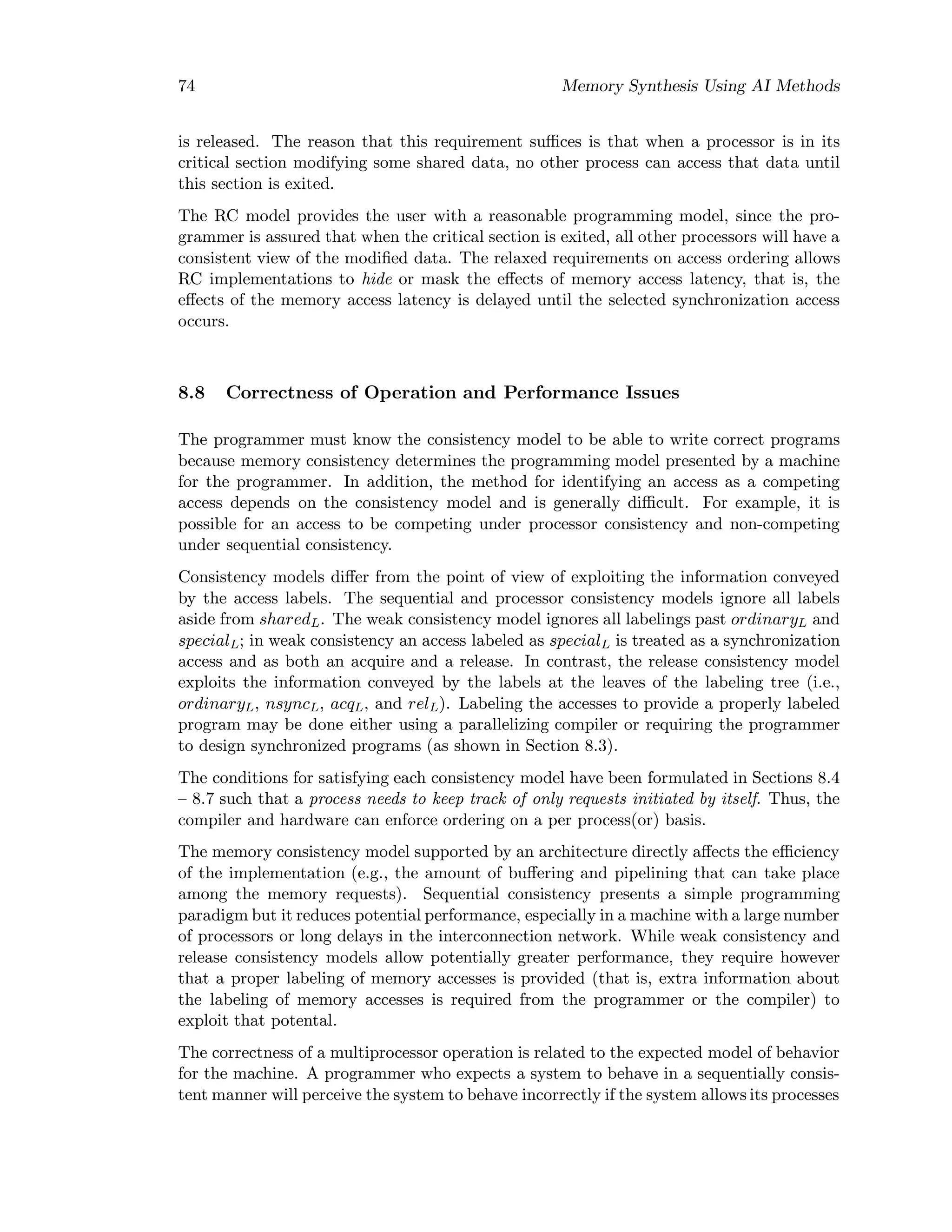

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 13

Processor 1

Processor 2

...

Processor n

Interconn Network

Memory

Memory

...

Memory

I/O

I/O

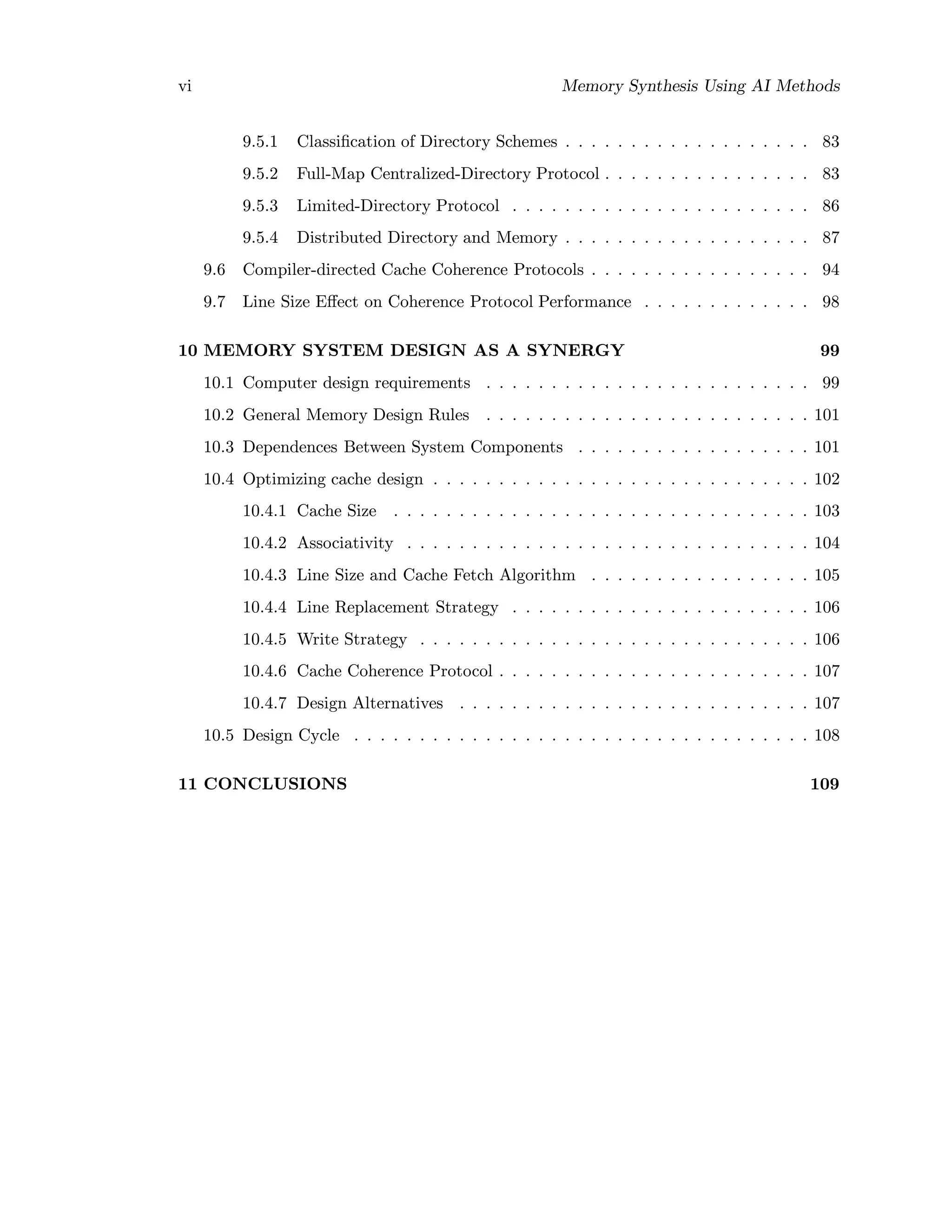

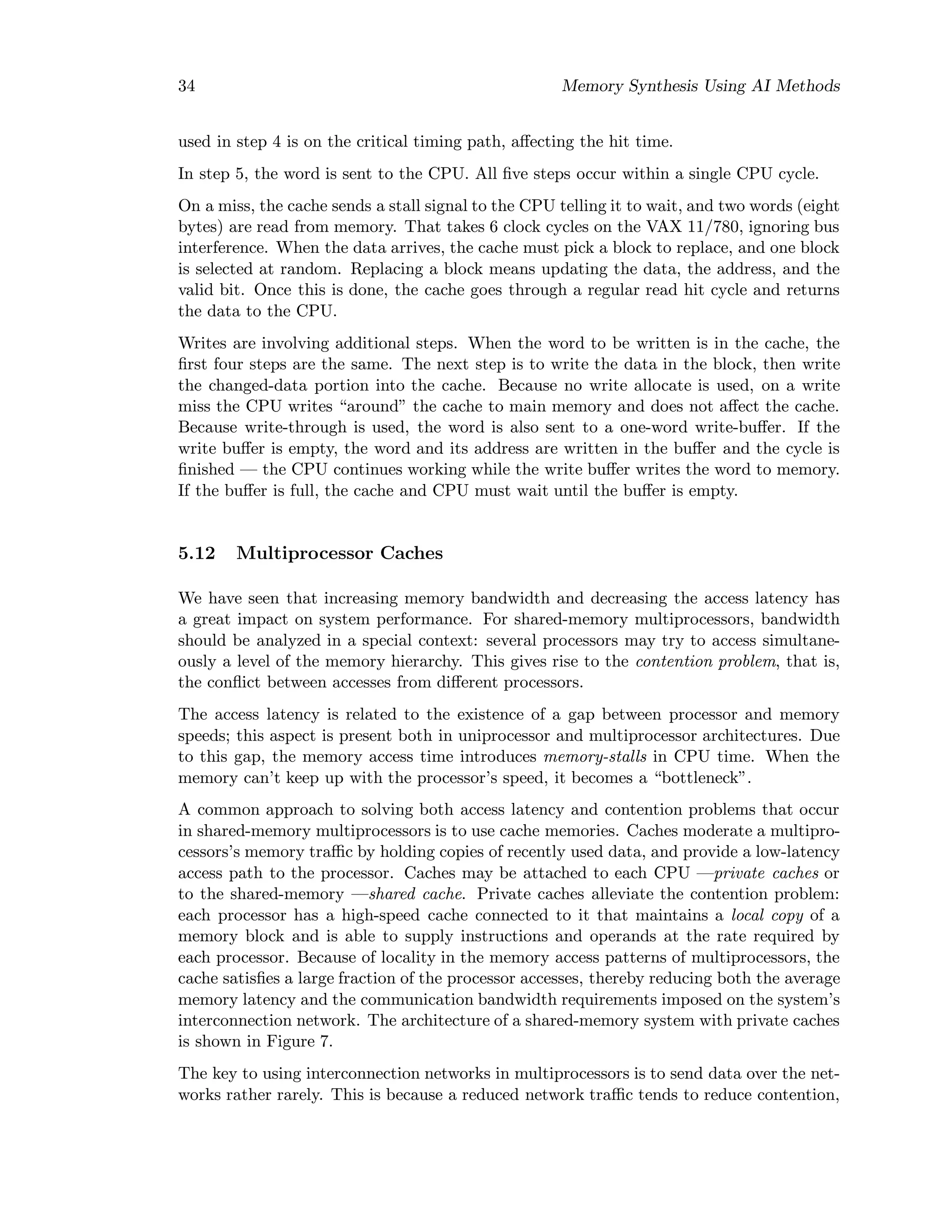

Figure 3: Shared-memory system: all memory and I/O are remote and shared

MIMD architecture is that multiple instruction streams must communicate or synchronize

by passing message or sharing memory.

4.2 Multiprocessors

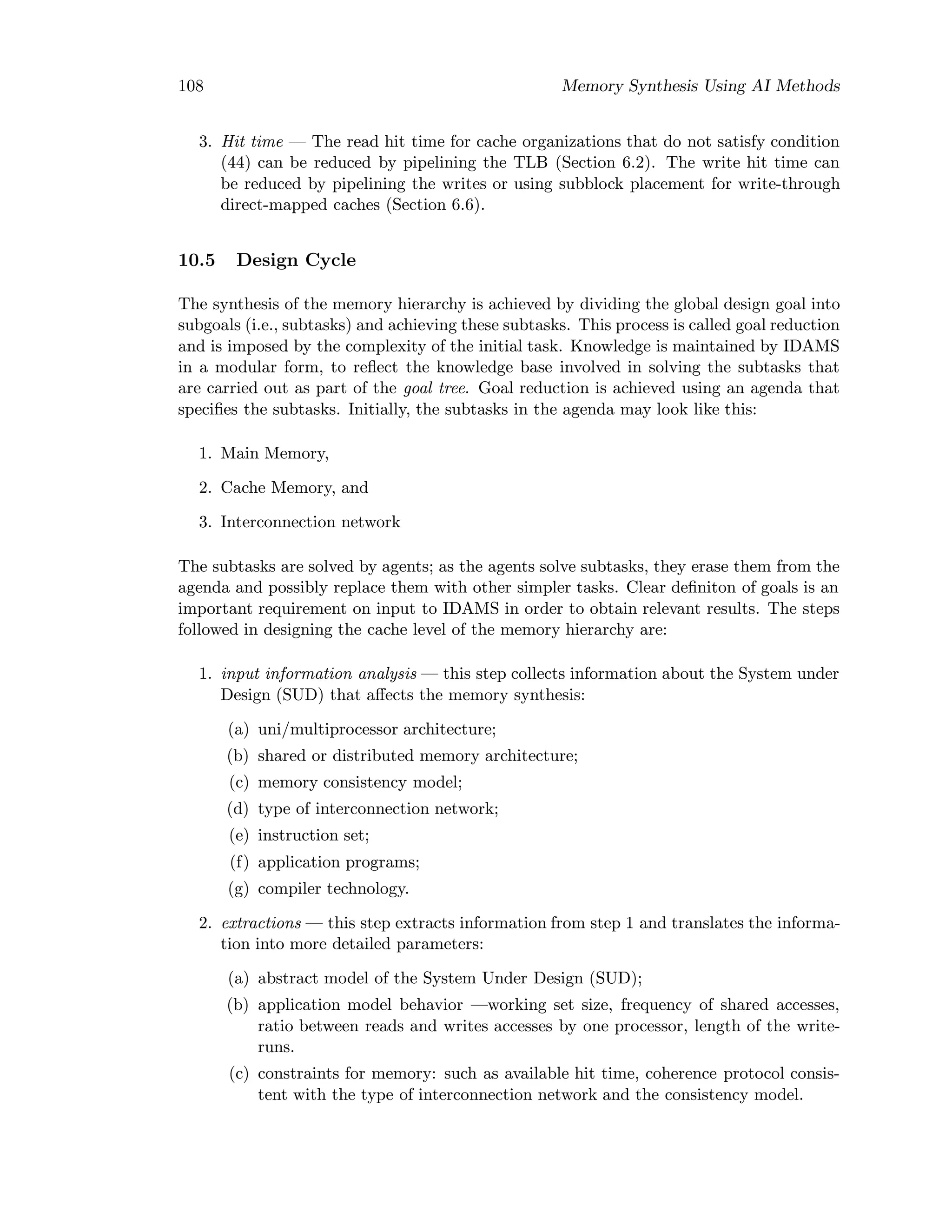

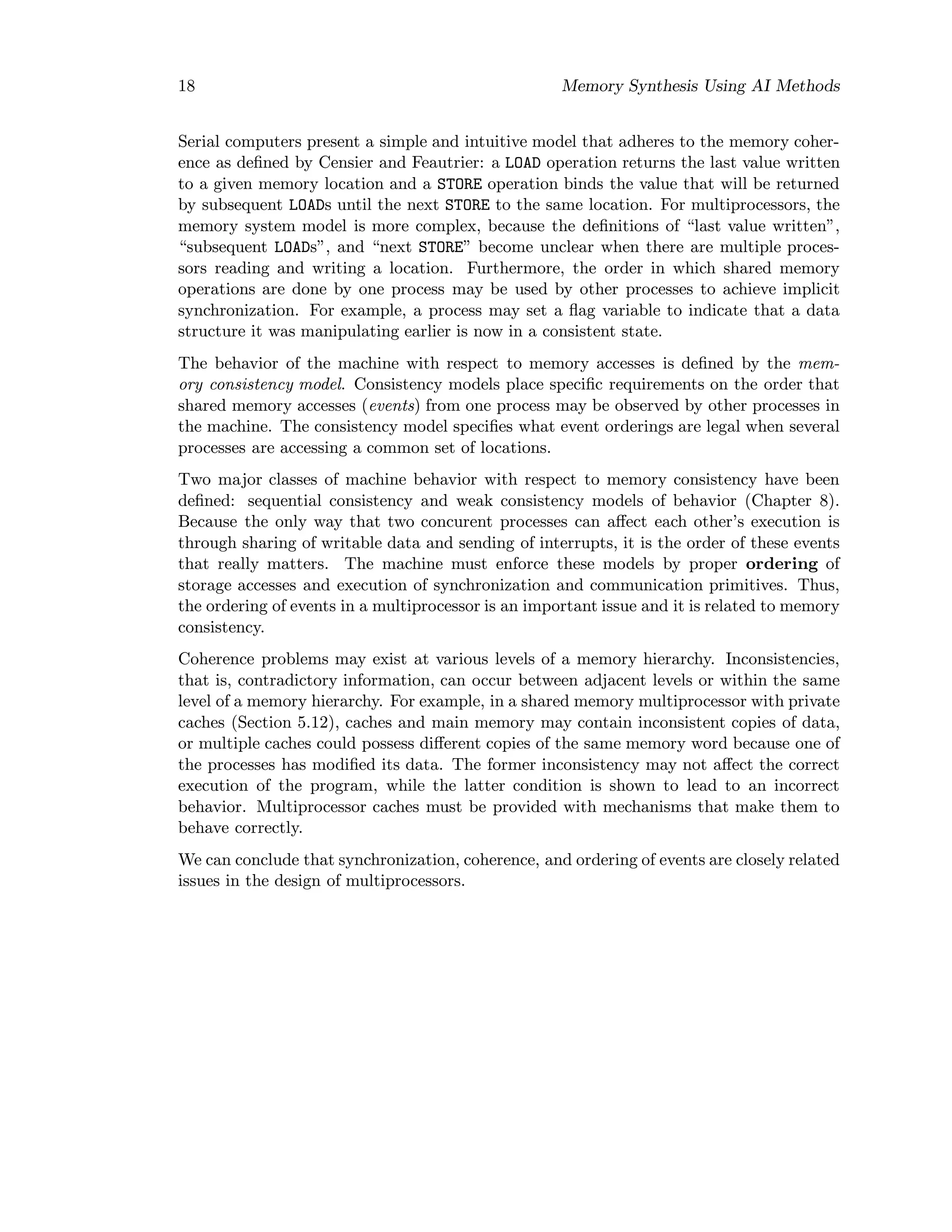

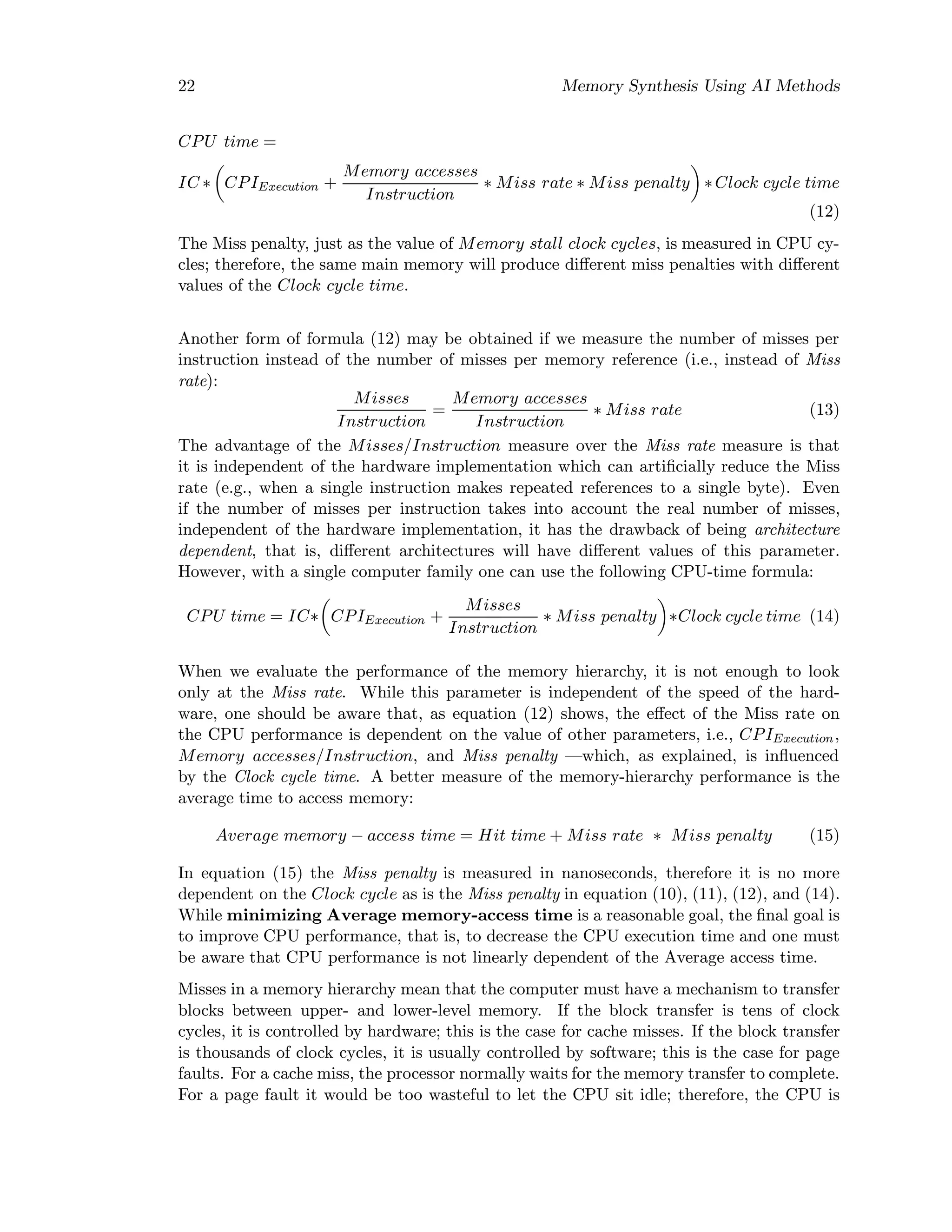

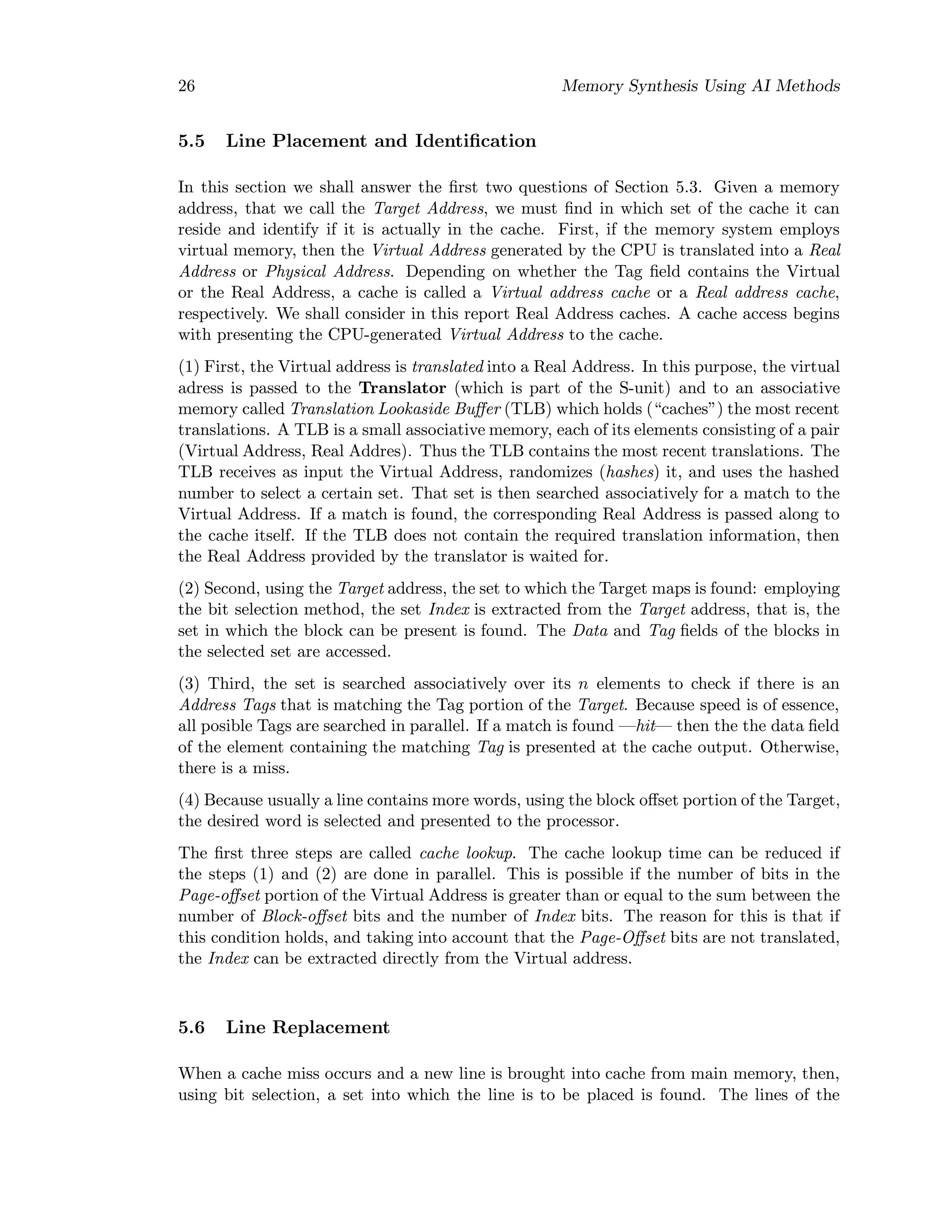

Among multiprocessors, we can distinguish two broad classes, according to the logical

architecture of their memory systems [7]:

• shared memory systems (also called tightly coupled systems): all processors access

a single address space (Figure 3).

• distributed systems (also called loosely coupled systems or multicomputers) : each

processor can access only its own memory; each processor’s memory is logically

disjoint from other processor’s memory (Figure 4). In order to communicate, the

processors are sending messages to each other.

A memory unit is called a memoru module. Each processor has registers, arithmetic and

logic units, and access to memory and input/output modules. The distinction between

the architectures stems from way memory and input/output units are accessed by the

processor:

• in the shared memory model, memory and I/O systems are separate subsystems

shared among all of the processors;

• in the distributed memory model, memory and I/O units are attached to individual

processors; no sharing of memory and input/output is permitted.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-19-2048.jpg)

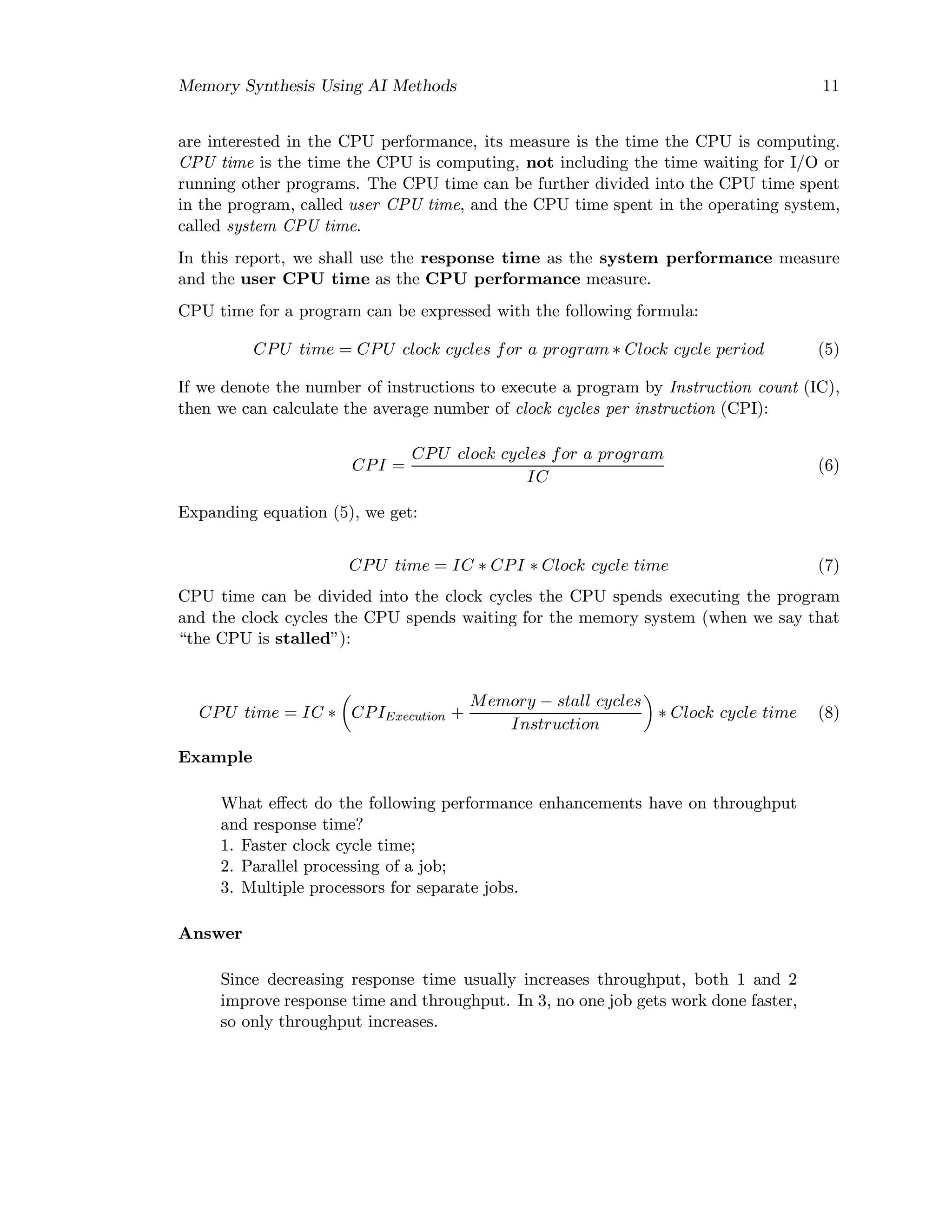

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 15

The distributed system (i.e., local and private memory and I/O) supports communication

through point-to-point exchange of information, usually by message passing.

Depending on the structure of the interconnection network, there are two types of shared-

memory architectures:

• bus-based memory systems: the memory and all processors (with optional private

caches) are connected to a common bus. In other words, communication on a bus

is of broadcast type: any memory access made by one CPU can be “seen” by all

CPU’s.

• general interconnection networks: they provide several simultaneous connections

between pairs of nodes, that is, only two nodes are involved in any connection: the

sender and the receiver. These interconnection networks adhere to the point-to-point

communication model and may be direct or multistage networks.

4.3 Multiprocessing performance

The main purpose of a multiprocessor is either to increase the throughput or to decrease

the execution time, and this is done by using several machines concurrently instead of

a single copy of the same machine. In some applications, the main purpose for using

multiple processors is for reliability rather than high performance; the idea is that if any

single processor fails, its workload can be performed by other processors in the system

(fault-tolerant computing). The design principles for fault-tolerant computers are quite

different from the principles that guide the design of high-performance systems. We shall

focus our attention on performance.

As mentioned in Section 3.2, the amount of overall Speedup is dependent on the fraction of

time that a given enhancement is actually used. In the case of improving performance by

using multiprocessing instead of uniprocessing, the overall efficiency is maximum when all

processors are engaged in useful work, no processor is idle, and no processor is executing

an instruction that would not be executed if the same algorithm were executing on a

single processor. This is the state of peak performance, when all N processors of a

multiprocessor are contributing to effective performance, and in this case the Speedup is

equal to N. Peak performance is rarely achievable because there are several factors ([7])

that introduce inefficiency, such as:

• the delays introduced by interprocessor communications;

• the overhead in synchronizing the work of one processor with another;

• lost efficiency when one or more processors run out of tasks;

• lost efficiency due to wasted effort by one or more processors;

• the processing costs for controlling the system and scheduling operations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-21-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 17

1. hardware level synchronization primitives such as TEST&SET(lock),

RESET(lock), FETCH&ADD(x,a), Empty/Full bit;

2. software-level synchronization mechanisms such as semaphores and barriers;

• message passing; This method can be used both for shared memory and distributed

systems.

Synchronization mechanisms are used to provide mutual exclusive access to shared variable

and to coordonate the execution of several processes:

Mutual exclusive access

Acces is mutually exclusive if no two processes access a shared variable simultaneously.

A critical section is an instruction sequence that has mutually exclusive access to shared

variables. Locks and semaphores can be used to guarantee mutual exclusive access. On a

uniprocessor, mutual exclusion can be guaranteed by disabling interrupts.

Conditional synchronization

Conditional synchronization is a method of process coordination which ensures that a set

of variables are in a specific state (condition) before any process requiring that condition

can proceed. Mechanisms such as Empty/Full bit, Fetch&Add, and Barrier can be used

to synchronize processes.

4.5 Coherence, Consistency, and Event Ordering

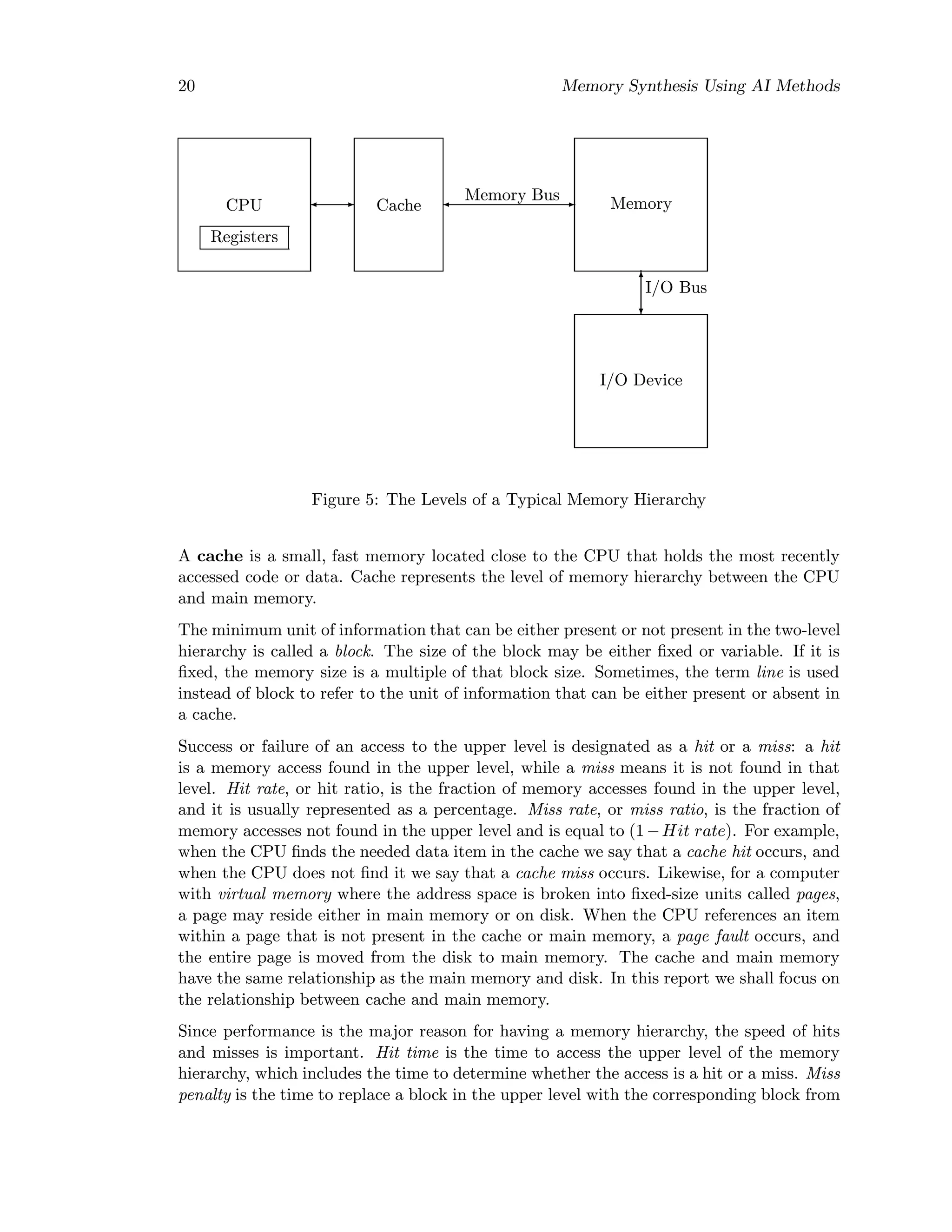

Memory coherence is a system’s ability to execute memory operation corectly. We need a

precise definition of correct execution. Censier and Feautrier define [1] a coherent memory

system as follows:

A memory scheme is coherent if the value returned on a LOAD opera-

tion is always the value given by the latest STORE operation with the

same address.

This definition, while very concise and intuitive, is difficult to interpret and too ambiguous

in the context of a multiprocessor, in which data accesses may be buffered and may not

be atomic.

An access by processor i on a variable X is called atomic if no other processor is allowed

to access any copy of X while the access by processor i is in progress.

A LOAD of a variable X s said to be performed at a point in time when issuing of a STORE

from any processor to the same address cannot affect the value returned by the LOAD.

A STORE on a variable X by processor i is said to be performed at a point in time when an

issued LOAD from any processor to the same address cannot return a value of X preceding

the STORE.

Accesses are buffered if multiple accesses can be queued before reaching their destination,

such as main memory or caches.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-23-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 31

This simple model of miss causes has some limits. For example, increasing cache size re-

duces capacity misses as well as conflict misses, since a larger cache spreads out references.

Thus, a miss might move from one category to the other as parameters change.

5.9 Line Size Impact on Average Memory-access Time

Let us analize the effect of the block size on the Average memory−access time (equation

(15), Section 5.2) by examining the effect of the line size on the Miss rate and Miss penalty.

We assume that the size of the cache is constant.

Larger block sizes reduce compulsory misses, as the principle of spatial locality suggests.

At the same time, larger block sizes increase conflict misses, because they reduce the

number of blocks in the cache. Reasoning in terms of the two aspects of the principle of

locality, we say that increasing line size lowers the miss rate until the reduced misses of

larger blocks (spatial locality) are outweighted by the increased misses as the number of

blocks shrinks (temporal locality), because larger block sizes means fewer blocks in cache.

Let us examine the effect of line size on the Miss penalty. The Miss penalty is the sum of the

access latency and the transfer time. The access-latency portion of the miss penalty is not

affected by the block size, but the transfer time does increase linearly with the block size.

If the access latency is large, initially there will be little additional miss penalty relative

to access time as block size increases. However, increasing the line size will eventuaslly

make the transfer-time become an important part of the miss penalty.

Since a memory hierarchy must reduce the Average memory-access time, we are interested

not in the lowest Miss rate, but in the lowest Average access time. This is related to

the product of Miss rate by the Miss penalty, according to equation (15), Section 5.2.

Therefore, the “best” line size is not that which minimizes Miss rate, but that which

minimizes the product between the Miss rate and the Miss penalty. Measurements on

different cache organizations and computer architectures have indicated that the lowest

average memory-access time is for line sizes ranging from 8 to 64-bytes ([6],[20]).

Of course, overall CPU performance is the ultimate performance test, so care must be taken

when reducing Average memory-access time to be sure that changes to Clock cycle time

and CPI improve overall performance as well as average memory-access time.

5.10 Operating System and Task Switch Impact on Miss Rate

When the Miss rate for a user program is analized (for example, by using a trace-driven

simulation), one should take into account that the real miss rate for a running program,

including the operating system code invoked by the program, is higher. The miss rate can

be broken into three components:

• the miss rate caused by the user program;

• the miss rate caused by the operating system code;

• the miss rate caused by the conflicts between the user code and the system code.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-37-2048.jpg)

![38 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

memory.

With respect to the second type of failure —associated with program migration—, let us

suppose that processor P1 is running a program that leaves in the cache the value 0 for

variable X. Then the program shifts to a different processor P2 and writes a new value

of 1 for variable X in the cache of that processor. Finally, the program shifts back to

processor P1 and attempts to read the current value of X. It obtains the old, stale value

of 0 when it should have obtained the new, fresh value 1 for X. Note that X does not

have to be a shared variable for this type of error to occur. The cause of this mode of

failure is ([7]) that a program’s footprint —that is, data associated with the program—

was not flushed completely from cache when the program has moved from P1 to P2 and

when it got back to P1 it has found there stale data.

The protocols that maintain cache coherence for multiple processors are called cache-

coherence protocols. This subject has been studied by many authors, among them being

Censier and Feautrier ([1]), Dubois and Briggs ([3],[4]), Archibald and Baer ([5]), Agarwal

([10]), Lenovski, Laudon, Garachorloo, Gupta and Hennessy ([17]), who have explored a

variety of cache-coherence protocols and examined their performance impact. Chapter 9

covers issues related to cache coherence. The implementation of cache in multiprocessors

may enforce coherence either totally by the hardware, or may enforce coherence only at

explicit synchronization points.

5.14 Cache Flushing

When a processor invalidates data in its cache, this is called flushing or purging. Sometimes

(Sections 5.13.1 and 9.6), it is necessary to invalidate the contents of more lines in cache,

i.e., to set the invalid bit for more lines. If this is done one line at time, the required time

would become excessive. Therefore, an INVALIDATE instruction should be available in the

processor if a coherence scheme based on flushing is used. If one chooses to flush the entire

cache, then resettable static random-access memories for Valid bits can be used allowing

the INVALIDATE to be accomplished in one or two clocks.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-44-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 41

if one copy is modified, the other will have the wrong value. Hardware schemes, called

anti-aliasing, that guarantee every cache line a unique physical address may be employed

to solve this problem, but software solution are less expensive. The idea of the software

solution is to force aliases to share a number of address bits so that the cache can not

accomodate duplicates of aliases. For example, for a direct mapped cache that is 256 KB,

that is 218KB, and if the operating system enforces that all aliases are identical in the last

18 bits of their addresses, then no two aliases can be simultaneously in cache. The third

problem is that I/O typically uses physical addresses and thus requires mapping to virtual

addresses to interact with a virtual cache in order to maintain coherence.

6.3 Reducing Read Miss Penalty

Because reads dominate cache accesses. it is important to make read misses fast. There

are several methods to reduce the read miss penalty. In the first method, called fetch

bypass or out-of-order fetch, the missed word is requested first, regardless of its position

in the line, data requested from memory is transmitted in parallel to the CPU and cache,

and the CPU waits only for the requested data, while in the second method, called early

restart, the line that contains the requested data is brought from memory starting with

the left-most byte, but the CPU continues execution as soon as the requested data arrives.

With fetch bypass, the missed word is requested first from memory and sent to the CPU as

soon as it arrives, bypassing the cache; the CPU continues execution while filling the rest

of the words in the block. Because the first word requested by the CPU may not be the

first word of a line, this strategy is also called out-of-order fetch or wrapped fetch. Usually,

the cache is loaded in parallel when the processor reads data from main memory (i.e., fetch

bypass with simultaneous cache fetch) in order to overlap fetching of the specified data for

CPU and for cache. When the transfer begins with a byte that is not the left-most byte

of the line, the transfer should wrap around the right-most byte of the line and transfer

the left-most bytes of the line that have been skipped in the first place.

This methods provide a reduction of the read miss penalty by obviating the need for the

processor to wait for the cache to load the entire line. Unfortunately, not all the words of

a line have an equal likelihood of being accessed first. If that were true, with a line size

of L bytes, the average line entry point would be L/2. However, due to sequential access,

the left side of the line is more likely to be accessed first. For example, Hennessy and

Patterson have determined [6] for some architecture that the average line entry point for

instruction fetch is at 5.6 bytes from the left-most byte in a 32-byte line. The left-word

of a block is most likely to be accessed first due to sequential accesses from prior blocks

on instruction fetches and sequentially stepping through arrays for data accesses. This

effect of spatial locality limits the performance improvement obtained with out-of-order

fetch. Spatial locality also affects the efficiency of early restart, because it is likely that the

next cache request be to the same line. The reduction in the read miss penalty obtained

with these methods should be compared to the increased complexity incurred by handling

another request while the rest of one line is being filled.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-47-2048.jpg)

![42 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

6.4 Reducing Conflict Misses in a Direct-Mapped Cache

As described in Section 5.8, conflict misses may appear when two addresses map into the

same cache set. Consider referencing a cache with two addresses, ai and aj. Using the bit

selection method described in Section 5.4, these two addresses will map into the same set

if and only if they have identical Index fields. Denoting by b the bit selection operation

performed on the addresses to obtain the index, then the two addresses will map into the

same set iff:

b[ai] = b[aj] (23)

Two addresses that satisfy this equation are called conflicting addresses because they may

potentially cause conflicts. Assume the following access pattern:

ai aj ai aj ai aj ai aj . . .

where addresses ai and aj are conflicting addresses. A 2-way set-associative cache will not

suffer a miss if the processor issues this adddress pattern because data referenced by ai

and aj can co-reside in a set. In contrast, in a direct-mapped cache, the reference to aj

will result in an interference (or conflict) miss because the data from ai occupies the same

selected line.

The percentage of misses that are due to conflicts varies widely among different applica-

tions, but it is often a substantial portion of the overall miss rate.

6.4.1 Victim Cache

The victim cache scheme has been proposed by Jouppi [12]. A victim cache is a small,

fully-associative cache that provides some extra cache lines for data removed from the the

direct-mapped cache due to misses. Thus, for a reference stream of conflicting addresses,

such as

ai aj ai aj ai aj ai aj . . .,

the second reference, aj, will miss and force the data indexed by ai out of the set. The

data that is forced out is placed in the victim cache. Consequently, the third reference, ai,

will not require accessing the main memory because the data can be found in the victim

cache. Fetching a conflicting datum with this scheme requires two or three clock cycles:

1. the first clock cycle is needed to check the primary cache;

2. the second cycle is needed to check the victim cache;

3. a third cycle may be needed to swap the data in the primary cache and victim cache

so that the next access will likely find data in the primary cache;

This scheme has several disadvantages: it requires a separate, fully-associative cache to

store the conflicting data. Not only does the victim cache consume extra area, but it can

also be quite slow due to the need for an associative search and for the logic to maintain a

least-recently-used replacement policy. For adequate performance a sizeable victim cache

is required in order for the victim cache to be able to store all conflicting data blocks. If

the size of the victim cache is fixed relative to the primary direct-mapped cache, then it

is not very effective at resolving conflicts for large primary caches.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-48-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 43

6.4.2 Column-Associative Cache

The challenge is to find a scheme that minimizes the conflicts that arise in direct-mapped

accesses by allowing conflicting addresses to dynamically choose alternate mapping func-

tions, so that most of the conflicting data can reside in the cache. At the same time,

however, the critical hit access path (which is an advantage of direct-mapped organiza-

tion) must remain unchanged. The method presented is called Column-Associativity and

has been invented by A. Agarwal and S.D. Pudar [11].

The idea is to emulate a 2-way set-associative cache with a direct-mapped cache by map-

ping two conflicting addresses to different sets instead of referencing another line in the

same set as the 2-way set-associativity does. Therefore, conflicts are not resolved within

a set but within the entire cache, which can be thought of as a column of sets —thus the

name column associativity. The method uses two mapping functions (also called hashing

functions) to access the cache. The first hashing function is the common bit selection,

that is, an address ai is mapped into the set with the number:

b[ai] (24)

The second hashing function is a modified bit-selection, which gives the same value as

the bit-selection function except for the highest-order bit, which is inverted. We call this

hashing function bit flipping and denote it by f. For example, if b[a] = 010, then applying

the bit flipping function to the address a yields f[a] = 110. Therefore, the function f

applied to an address aj will always give a set number which is different from that given

by the function b:

b[aj] = f[aj] (25)

The scheme works as follows:

1. the bit selection function b is applied to a memory address ai. If b[ai] indexes to

valid data, a first-time hit ocurs, and there is no time penalty;

2. if the first access has missed, then the bit flipping function f is used to access the

cache. If f[ai] indexes to valid data, then a second-time hit occurs and data is

retrieved.

3. if a second-time hit has occured, then the two cache lines are swapped so that the

next access will likely result in a first-time hit.

4. if the second access misses, then data is retrieved from main memory, placed in the

cache set indexed by f[ai], then it is swapped with the data indexed by b[ai] with

the goal of making the next access likely to be a first-time hit.

The first and second step each require one clock cycle, while swapping requires two clock

cycles. The second-time hit, including swapping, is then four cycles but can be reduced

to only three cycles using an extra buffer for the cache: Given this buffer, the swap need

not involve the processor, which may be able to do other useful work while waiting for the

cache to become available again. If this is the case half of the time, then the time wasted](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-49-2048.jpg)

![44 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

by a swap is only one cycle. Therefore, it can be considered that a swap adds only one

cycle to the execution time, and hence the second-time hit is 3 clock cycles.

Using two hashing functions mimics 2-way set-associativity because for two conflicting

addresses, ai and aj, rehashing aj with f resolves the conflict with a high probability: from

equations (23) and (25) it results that the function f applied to aj will give a set different

from b[ai]:

b[ai] = b[aj] = f[aj] (26)

The difference is that a second-time hit takes three clock cycles, while in a 2-way set-

associative cache the two lines of a set can be retrieved in a clock cycle. However, the

clock cycle of the two-way set-associative cache is longer that the clock cycle of the direct-

mapped cache.

A problem that must be solved for column-associative caches is the problem of possible

incorrect hits. Consider two addresses, ai and ak, that map with bit-selection to indexes

that differ only in the highest-order bit. In this case, the index obtained by applying bit-

selection mapping to one address is the same as the index obtained by applying bit-flipping

mapping to the other address:

b[ak] = f[ai] and b[ai] = f[ak] (27)

These two addresses are distinct, but they may have identical tag fields. If this is the case,

when a rehash occurs for the address ai and data addressed by ak is already in cache at

location b[ak], then the bit-flipping mapping f[ai] results in a hit with a data block that

should only be accessed by b[ak]. For example, if

b[ak] = 110, b[ai] = 010, and Tag[ak] = Tag[ai] (28)

and assuming that data line addressed by ak is cached in the set with the index b[ak], then

when the address ai is presented to the cache, this address will be rehashed to the same

set as ak (i.e., f[ai] = 110) and will cause a second-time hit (a false hit) because the two

addresses have the same Tag. This is incorrect, because a data-line must have a one-to-one

correspondence with a unique memory address. The solution to this problem is to extend

the Tag with the highest-order bit of the index field. In this case, the rehash with f[ai]

will correctly fail because information about ai and ak having different indexes is present

in the Tag. In this way, the data line stored in the set with the number b[ak] = f[ai] is

put into correspondece with an unique index, and hence a unique address.

Another problem is that storing conflicting data in another set is likely to result in the

loss of useful data, and this is referred to as clobbering. The source of this problem

is that a rehash is attempted after every first-time miss, which can replace potentially

useful data in the rehashed location, even when the primary location had an inactive

line. Clobbering may lead to an effect called secondary thrashing that is presented in the

following paragraph.

Consider the following reference pattern:

ai aj ak aj ak aj ak . . . ,

where the addresses ai and aj map into the same cache location with bit selection, and ak](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-50-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 45

is an address which maps into the same location with bit-flipping, that is:

b[ai] = b[aj], b[ak] = f[ai] and f[ak] = b[ai] (29)

After the first two references, the data referenced by aj (which will be called j for brevity)

and the data i will be in the non-hashed and rehashed locations, respectively (because of

swapping). When the next address, ak, is encountered, the algorithm attempts to access

b[ak] (bit selection is tried first), which contains the rehashed data i; when the first-time

miss ocurs, the algorithm tries to access f[ak] (bit flipping is tried second), which results

in a second-time miss and the clobbering of the data j. This pattern continues as long

as aj and ak alternate: the data referenced by one of them is clobbered as the inactive

data block i is swapped back and forth but never replaced. This effect is referred to as

secondary thrashing.

The solution to this problem is finding a method to inhibit a rehash access if the location

reached by the first-time access itself contains a rehashed data block, that is, with the

previous notation, when the location referenced by ak with bit-selection (b[ak]) already

contains a rehashed data (data i is rehashed to f[ai]). This condition can be satisfied by

adding to each cache set an extra bit that indicates whether the set is a rehashed location,

that is, whether the data in that set is indexed by f[a]. This bit that indicates a rehashed

location is called the rehash bit, denoted by Rbit, and it makes possible to test if a first-

time miss occurs on a rehashed data and thus to avoid rehashing a first-time miss to a

set that contains rehashed data. Therefore, the scheme for column associativity is the

following (step 2 of the the basic scheme is modified to avoid clobbering):

1. the bit-selection hashing function b is applied to a memory address a. If b[a] indexes

to valid data, a first-time hit ocurs, and there is no time penalty;

2. if the first access is a miss, then the action taken depends on the value of the rehash

bit of the set indexed by b[a]:

(a) if the rehash bit has been set to one, then no rehash access will be attempted,

but the data retrieved from memory will be placed in the location obtained by

bit-selection. Then the rehash bit for that set will be reset to zero to indicate

that the data in this set is indexed by bit-selection and the access is completed.

(b) if the rehash bit is already a zero, then the bit-flipping function f is used to

access the cache. If f[a] indexes to valid data, then a second-time hit occurs

and data is retrieved;

3. if a second-time hit has occured, then the two cache lines are swapped so that the

next access will likely result in a first-time hit.

4. if the second access misses, then data is retrieved from main memory, placed in the

cache set indexed by f[a], then it is swapped with the data indexed by b[a] with the

goal of making the next access likely to be a first-time hit.

Note that if a second-time miss occurs, then the set whose data will be replaced is again a

rehashed location, as desired. At start-up (or after a cache flush), all of the empty cache](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-51-2048.jpg)

![46 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

locations should have their rehash bits set to one. The reason that this scheme correctly

replaces a location that has the Rbit set to one immediately after a first-time miss is based

on the the relationship between bit selection and bit-flipping mapping: given two addresses

ai and ak, if f[ai] = b[ak] then f[ak] = b[ai]. Therefore, if ai accesses a location using b[ai]

whose rehash bit bit is set to one, then there are only two possibilities:

1. The accessed location is an empty location from start-up, or

2. there exists a non-rehashed location at f[ai] (that is, b[ak]) which previously encoun-

tered a conflict and placed the data in its rehashed location, f[ak].

In both cases replacing the location reached during first-time access that has the Rbit set

to one is a good action, because data at location b[ai] is less useful than data at location

f[ai] = b[ak].

The rehash bits limit the rehash accesses and the clobbering effect, and lower the proba-

bility of secondary thrashing. For the mentioned reference stream:

ai aj ak aj ak aj ak . . . ,

the third reference accesses b[ak], but it finds the rehash bit set to one, because this loca-

tion contains the data referenced by ai. Therefore, the data i is replaced immediately by

k, the desired action. Even though the column-associative cache can present secondary

thrashing if three or more conflicting addresses alternate, as in the pattern:

ai aj ak ai aj ak ai aj . . . ,

this case is much less probable than two alternating addresses.

6.5 Reducing Read Miss Rate

When the processor makes a memory reference that misses in the cache, then the line

corresponding to that memory address is fetched from memory. If no line is fetched until

it is referenced by the processor, one calls this demand fetching, that is no line is fetched

in advance from memory.

When a line is fetched from memory and brought into cache before it is requested by

the processor, one calls this a prefetch operation. The purpose of prefectch is to bring in

advance information that will soon be needed by the processor, and in this way to decrease

the miss rate. A prefetch algorithm guesses what information will soon be needed and

fetches it. When a prefetch algorithm decides to fetch a line from memory, it should

interrogate the cache to see if that line is already resident in cache. This is called prefetch

lookup and may interfere with the actual cache lookups generated by the processor. Given

that a prefetch may require to replace an existing line, this interference consists not only

in cycles lost by the CPU when waiting for the prefetch lookup cache accesses, or in cache

cycles used to bring in the prefetched line and perhaps to move out a line from cache, but

also in a potentially increase in miss ratio when lines that are more likely to be referenced

are expelled by a prefetch. This problem is called memory pollution and its impact depends

on the line size. Small line sizes generally result in a benefit from prefetching, while large

line sizes lead to the ineffectiveness of prefetch. The reason for this is that when the line](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-52-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 49

1. Tag match and valid bit already set. Writing the block was the proper action, and

nothing was lost by setting the valid bit on again.

2. Tag match and valid bit not set. The tag match means that this is the proper block;

writing the data into the block makes it appropriate to turn the valid bit on.

3. Tag mismatch. This is a miss and will modify the data portion of the block. However,

as this is a write-through cache, no harm was done; memory still has an up-to-date

copy of the old value. Only the tag to the address of the write need be changed

because the valid bit has already been set. If the block size is one word and the

STORE instruction is writing one word, then the write is complete. When the block

is larger than a word or if the instruction is a byte or halfword store, then either the

rest of the valid bits are turned off (allocationg the subblock without fetching the

rest of the block) or memory is requested to send the missing part of the block (i.e.,

write allocate).

This scheme can’t be used with a write-back cache because the only valid copy of the data

may be in the block, and it could be overwritten before checking the tag.

6.7 Reducing Write Stalls

Write stalls may occur at every write for write through or when a dirty line is replaced

for write back strategy, and they can be avoided using a write buffer (described in Section

5.7) of a proper size. Write buffers, however, introduce additional complexity for handling

misses because they might have the updated value of a location needed on a read miss.

For write through, the simplest solution to solve this problem is to delay the read until

all the information in the write buffer has been transmitted to memory, that is, until the

write buffer is empty. But, since a write buffer usually has room for a few words, it will

almost always have data not yet transferred, that is, it will not be empty, which incurs

an increase in the Read Miss Penalty. This increase may reach as much as 50% for a

four-word buffer as stated by Hennessy and Patterson in [6]. An alternative approach is

to check the contents of the write buffer on a read miss, and if there are no conflicts and

the memory system is available, let the read miss continue.

For write back, the buffer (whose size is one line in this case) may contain a dirty line that

has been purged from cache to make room for a new line but has not yet been written

into memory that still contains the old data. When a read miss occurs, there are also

two approaches: either to wait until the buffer is empty, or to check if it contains the

referenced line and to continue with the memory access if there is no conflict.

6.8 Two-level Caches

6.8.1 Reducing Miss Penalty

The gap between the CPU and main memory speeds is increasing due to CPUs getting

faster and main memories getting larger, but slower relative to the faster CPUs. The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-55-2048.jpg)

![56 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

FETCH&ADD(x, a)

{ temp = x; x = temp + a;

return temp; }

When N processes attempt to execute FETCH&ADD on the same memory word x simultane-

ously, the memory is updated only once, by adding the sum of the N increments, and each

of the N processes receives a returned value that corresponds to an arbitrary serialization

of the N requests. From the processor point of view, the result is similar to a sequential

execution of N FETCH&ADD instructions, but it is performed in one memory operation. The

success of this primitive is based on the fact that its execution is distributed in the inter-

connection network using a combining interconnection network (Subsection 7.4.1) that is

able to combine more accesses to a memory location into a single access. In this way, the

complexity of an N-way synchronization on the same memory word is independent of N.

This method for incrementing and decrementing has benefits as compared with the use of a

normal variable protected by a lock to achieve the atomic increment or decrement, because

it involves less traffic, smaller latency and decreased serialization. The serialization of this

primitive is small because it is done directly at the memory site. This low serialization is

important when many processors want to increment a location, as happens when getting

the next index in a parallel loop. A multiprocessor using a combining network and this

primitive is the IBM RP3 computer ([3]). FETCH&ADD is useful for implementing several

synchronization methods such as barriers, parallel loops, and work queues.

7.2.3 Full/Empty bit primitive

Under this primitive, a memory location is tagged as empty or full.

LOADs of such words succeed only after the word is updated and tagged as full. After a

successful LOAD, the tag is reset to empty. Similarly, the STORE on a full memory word can

be prevented until the word has been read and the tag cleared.

This primitive relies on busy-waiting, and memory cycles are wasted on each trial: when

a process attempts to execute a LOAD on an empty-tagged location, the proces will spin on

the CPU while waiting for the location to be tagged as full. By analogy with the locks,

one says that the process spin-locks on the Full/Empty bit.

This mechanism can be used to synchronize processes, since a process can be made to wait

on an empty memory word until some other process fills it.

7.3 Synchronization Methods

In this section we present methos for achieving mutual exclusion and conditional synchro-

nization.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-62-2048.jpg)

![60 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

7.4 Hot Spots in Memory

When accesses from several processors are concentrated to data from a single memory

module over a short duration of time, the access pattern is likely to cause hot spots in

memory. A hot spot is a memory location repeatedly accessed by several processors. Syn-

chronization objects such as locks and barriers, and loop index variables for parallel loops

are examples of shared variables that can become hot spots. Hot spots can significantly

reduce the memory and network throughput because they do not allow parallelism of

the machine architecture to be exploited as it is possible under unifrom memory access

patterns. Hot spots can cause severe congestion in the interconnection network, which

degrade the bandwidth of the shared-memory system.

7.4.1 Combining Networks

An widespread scheme to avoid memory contention is the combining network. The idea

is to incorporate some hardware in the interconnection network to trap and combine data

accesses when they are fanning in to a memory module that contains the shared variable.

By combining data accesses in the interconnection network the number of accesses to the

shared variable is decreased. The extra hardware required for this scheme is estimated in

[15] to increase the switch size and/or cost by a factor between 6 and 32 for combining

networks consisting of 2 × 2 switches. The extra hardware also tends to add extra net-

work delay which will penalize most of the ordinary data accesses that do not need these

facilities, unless the combining network is built separately.

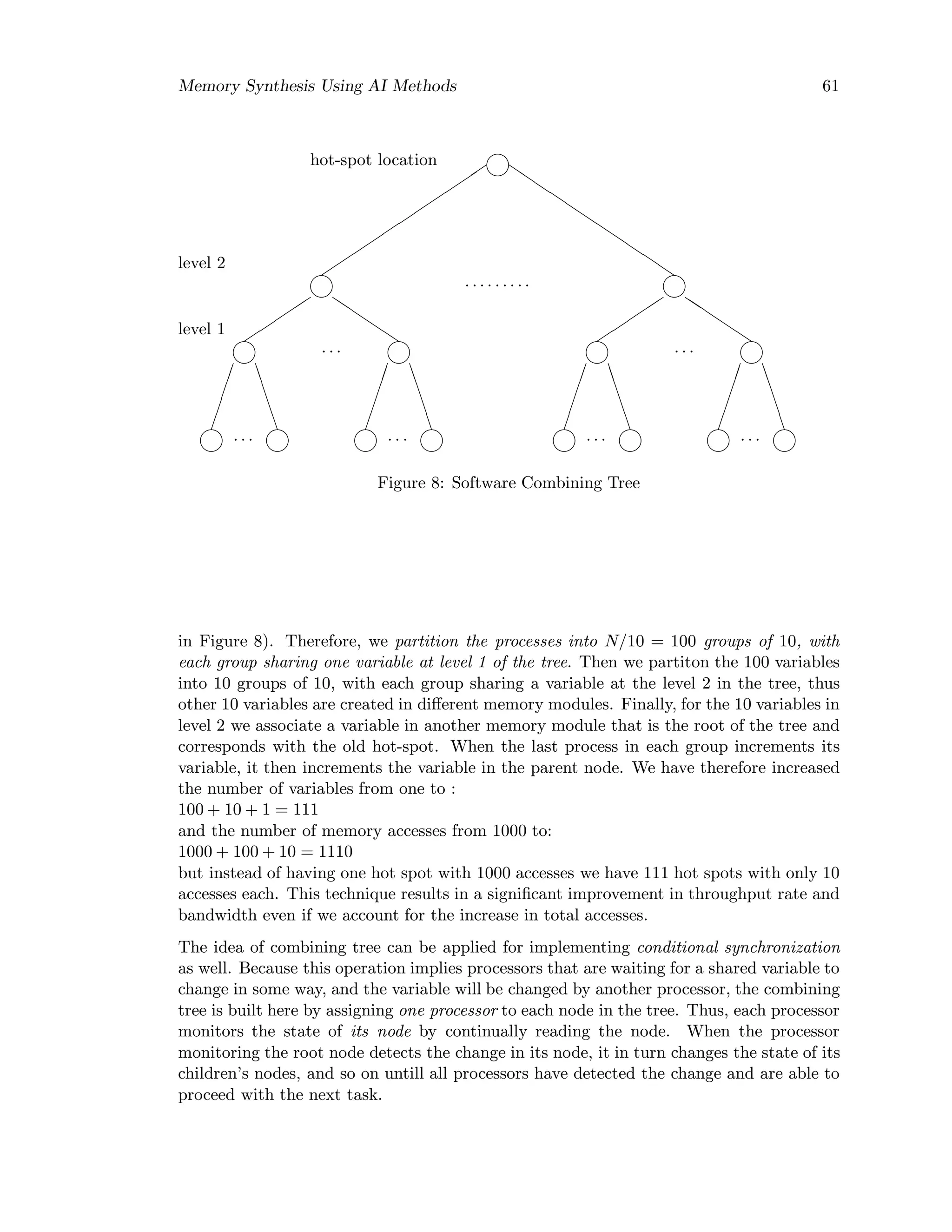

7.4.2 Software Combining Trees

A software tree can be used to eliminate memory contention due to the hot-spot variable.

The idea is similar to the concept of a combining network, but it is implemented in

software instead of hardware. A software combining tree is used to do the combining of

data accesses. This technique, that has been proposed by Yew et al. in [16], does not

require expensive hardware combining, while providing comparable performance. The

principle of a software combining tree is first illustrated for a barrier variable.

Let us assume a multiprocessor architecture with N processors and N memory modules.

We define the fan-in of the accesses to a memory location as the number of accesses to that

location. We assume a that a hot-spot with a fan-in of N exists in the system, for example

when a barrier variable (Sectuion 7.3.4) is used to make sure that all processors are finished

with a given task before proceeding. Therefore, the barrier variable is addressed by the

N processors, causing a hot-spot with a fan-in of N. The barrier variable has initially the

value zero, and each of N processors has to increment this variable so that when when all

processors are finished, the value will be N. Assuming that N = 1000, we have a hot-spot

with 1000 accesses. The software combining tree is replacing the single variable with a

tree of variables, with each variable in a different memory module. For the example given,

if we decide to reduce the fan-in to 10, then for each group of 10 processors, a variable

is created in a different memory module, for a total of 100 variables (level 1 of the tree](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-66-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 63

8 SYSTEM CONSISTENCY MODELS

The memory consistency model is the set of allowable memory access (events) ordering.

Consistency models place requirements on the order that events from one process may be

observed by other processes in the machine. The memory consistency model defines the

logical behavior of the machine on the basis of the allowable order (sequence) of execution

within the same process and among different processes.

For the memory to be consistent, two necessary conditions must be met:

1. the memory must be kept coherent, that is, all writes to the same location are

serialized in some order and are performed in that order with respect to any

processor;

2. uniprocessor data and control dependences must be respected (this is the responsi-

bility of the hardware and the compiler) — this is required for local-level consistency.

Several memory consistency models have been proposed ([13]), such as sequential consis-

tency, processor consistency, weak consistency, and release consistency. Sequential consis-

tency is the strictest model and it requires the execution of a parallel program to appear as

some interleaving of the execution of the parallel processes on a sequential machine. This

model offers a simple conceptual programming model but limits the amount of hardware

optimization that could increase performance. The other models attempt to relax the con-

straints on the allowable event orderings, while still providing a reasonable programming

model for the programmer.

The architectural organization of a system may or may not inherently support atomicity

of memory accesses. While memory accesses are atomic in systems with a single copy of

data (a new value becomes visible to all processors at the same time), such atomicity may

not be present in cache-based systems. The lack of atomicity introduces extra complexity

in implementing consistency models. Caching of data also complicates the ordering of

accesses by introducing multiple copies of the same location. When the bus is not the

interconnection network, but general interconnection networks are used instead (non bus-

based systems), the invalidations sent by a cache may reach the other caches in the system

at different moments. Waiting for all nodes connected to the network to receive the

invalidation and to send the acknowledge would cause a serious performance penalty. As

a result of the distributed memory system and general interconnection networks being

used by scalable multiprocessor architectures (for example, the DASH architecture [9,17]

presented in Section 9.5.4), requests issued by a processor to distinct memory modules may

execute out of order. Consequently, when distributed memory and general interconnection

networks are used, performance would benefit if the consistency model allows accesses to

perform out of order, as long as local data and control dependences are observed.

The expected logical behavior of the machine must be known by the programmer in order

to write correct programs. The memory consistency has a direct effect on the complexity

of the programming model presented by a machine for the programmer.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-69-2048.jpg)

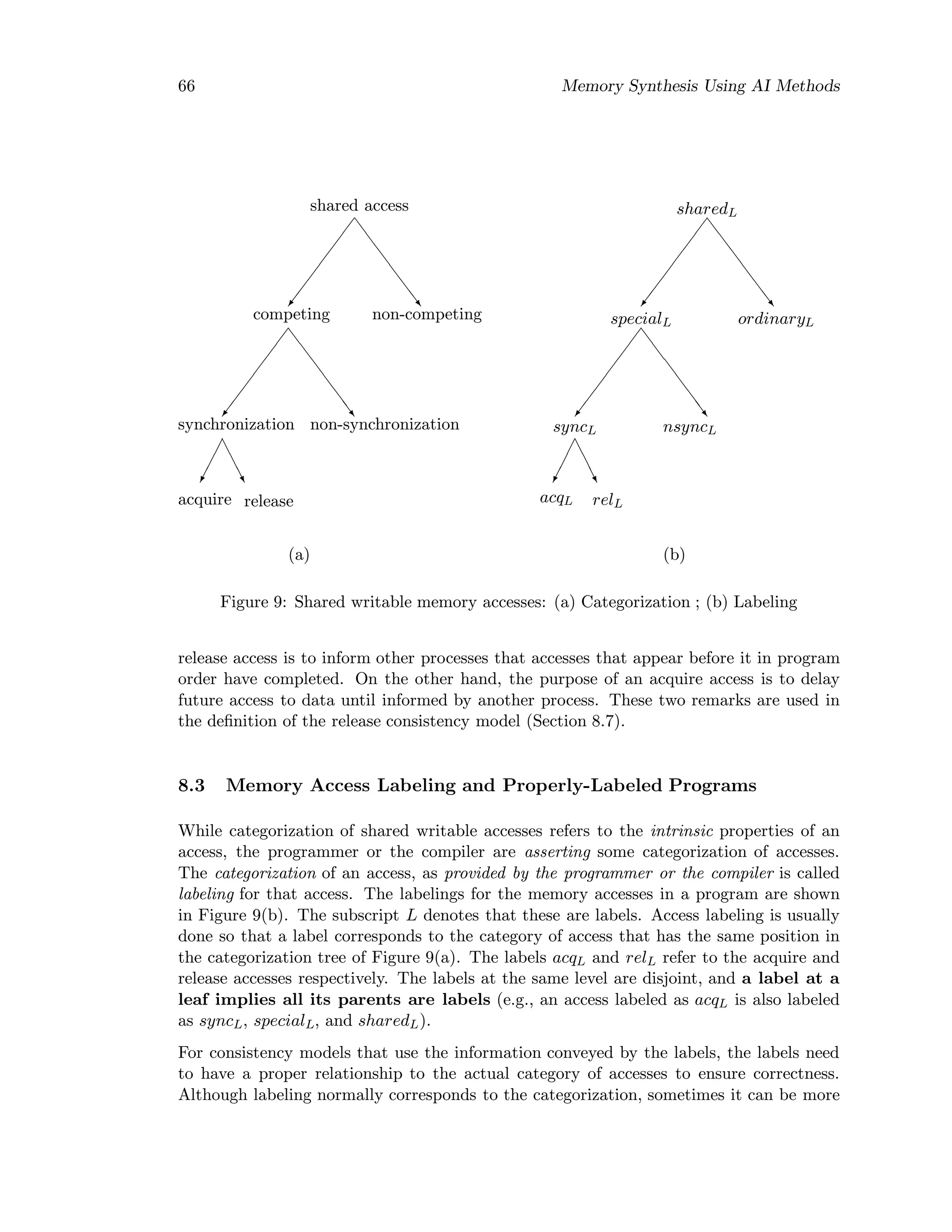

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 67

conservative than categorization. For example, the ordinaryL label asserts that an access

is non-competing. Since hardware may exploit the ordinaryL label to use less strict event

ordering, it is important that the ordinaryL label be used only for non-competing accesses.

However, a non-competing access can be labeled conservatively as specialL (thus, in some

cases a distinction between the categorization and the labeling of an access is made).

To ensure that accesses labeled ordinaryL are indeed non-competing, it is important that

enough competing accesses (i.e., accesses labeled as specialL) be labeled as acqL and relL.

The difficulty of ensuring enough syncL labels for a program depends on the amount of

information about the category of accesses, but it is shwon farther in this section that the

problem can be solved by following a conservative labeling strategy. Because labels at the

same level are disjoint and a label at a leaf implies all its parent labels, it follows that:

(1) an acqL or relL label implies the syncL label, and

(2) any specialL access that is not labeled as syncL is labeled as nsyncL, and

(3) any sharedL access that is not labeled as specialL is labeled as ordinaryL.

The LOAD and STORE accesses in a program are labeled based on their categorization. The

atomic read-modify-write (such as the TEST&SET primitive) provided by most architectures

is labeled by seeing it as a combination of a LOAD access and a STORE access and by labeling

separately each access based on its categorization. The common labeling for a TEST&SET

primitive is an acqL for the LOAD access and a nsyncL for the STORE access, because the

STORE access does not function as a release. If the programmer or the compiler cannot

categorize an RMW appropriately, then the conservative label for guaranteeing correctness

is: acqL for the LOAD and relL for the STORE part of the RMW.

When all accesses in a program are appropriately labeled, the program is called a properly-

labeleled (PL) program. The conditions that ensure that aprogram is properly labeled are

given in [13]:

Condition for Properly-Labeled (PL) Programs

A program is properly-labeled if the following hold:

(shared access) ⊆ sharedL, competing ⊆ specialL,

and enough special accesses are labeled as acqL and relL.

There is no unique labeling to make a program a PL program, that is, there are several

labelings that respect the previous subset properties. Given perfect information about the

category of an access, the access can be easily labeled making the labels (Figure 9(b)) to

correspond to the categorization of accesses (Figure 9(a)). When perfect information to

make labeling is not available, proper labeling can still be provided by being conservative.

The three possible labeling strategies (from conservative to aggressive) are:

1. If competing and non-competing accesses can not be distinguished, then all reads

can be labeled as acqL and all writes can be labeled as relL.

2. If competing accesses can be distinguished from non-competing accesses but syn-

chronization and non-synchronization accesses can not be distinguished, then all

accesses distinguished as non-competing can be labeled as ordinaryL and all com-

peting accesses are labeled as acqL and relL (as in strategy (1)).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-73-2048.jpg)

![68 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

3. If competing and non-competing accesses are distinguished and synchronization and

non-synchronization accesses are distinguished, then all non-competing accesses can

be labeled as ordinaryL, all non-synchronization accesses are labeled as nsyncL and

all synchronization accesses are labeled as acqL and relL (as in strategy (1)).

There are two practical ways for labeling accesses to provide properly-labeled (PL) pro-

grams. The first involves parallelizing compilers that generate parallel code from sequential

programs. Since the compiler does the parallelization, the information about which ac-

cesses are competing and which accesses are used for synchronization is known to the

compiler and can be used to label the accesses properly. The second way of producing PL

programs is to use a programming methodology that leads itself to proper labeling. For

example, a large class of programs are written such that accesses to shared data are pro-

tected within critical sections. Such programs are called synchronized programs, whereby

writes to shared locations are done in a mutually exclusive manner. In a synchronized pro-

gram, all accesses (except accesses that are part of the synchronization constructs) can be

labeled as ordinaryL. In addition, since synchronization constructs are predefined, the ac-

cesses within them can be labeled properly when the constructs are first implemented. For

this labeling to be proper, the programmer must ensure that the program is synchronized.

8.4 Sequential Consistency Model

The strictest consistency model is called Sequential Consistency (SC) and has been defined

by Lamport [2] as follows:

A system is sequentially consistent if the result of any execution

of a program is the same as if the operation of all the processors

were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each

individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified

by its program.

In other words, the sequential consistency model requires execution of the parallel program

to appear as some interleaving of the execution of the parallel processes on a sequential

machine. An interleaving that is consistent with the program order is called legal inter-

leaving. Application of the above definition requires a specific interpretation of the terms

operations and result. Operations are memory accesses (reads, writes, and read-modify-

writes) and result refers to the union of values returned by all the read operations in the

execution and the final state of memory. The definition of sequential consistency can be

translated in the following two conditions:

(1) all memory accesses appear to execute atomically in some total order, and

(2) all memory accesses of each processor appear to execute in an order specified by its

program, that is, in program order.

Speaking in event ordering terms, a sequential consistent memory assures that the execu-

tion of processes is such that there is a total order of memory accesses that is consistent

with the program order of each process. Under sequential consistency, identification of

accesses that form a competing pair can be achieved with the following criterion: Two](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-74-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 69

conflicting accesses a1 and a2 on different processes form a competing pair if there exists

at least one legal interleaving where a1 and a2 are adjacent. Assuming the SC model, the

following criterion (given in [13]) may be used for determining whether enough accesses

are labeled as syncL (i.e., as acqL and relL)

Condition for enough syncL labels

Pick any two accesses u on processor Pu and v on processor Pv (Pu not the same as Pv),

such that the two accesses conflict and at least one is labeled as ordinaryL. If v appears

after (before) u under any interleaving consistent with the program order, then there needs

to be at least one relL (acqL) access on Pu and one acqL (relL) on Pv separating u and v,

such that the relL appears before the acqL. There are enough accesses labeled as syncL

—that is, relL and acqL labeled accesses— if the above condition holds for all possible

pairs u and v.

The SC model ignores all access labelings past sharedL. In systems that are sequentially

consistent we say that events are strongly ordered: the order in which events are generated

by a processor is the same as the order in which all the other processors observe the

events, and events generated by two different processors are observed in the same order

by all other processors.

8.4.1 Conditions for Sequential Consistency

Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for SC in Systems with Atomic Accesses

It has been shown by Dubois et al. ([3]) that the necessary and suficient condition for a

system with atomic memory accesses to be sequentially consistent is that memory accesses

be performed in program order.

In architectures with caches and general interconnection networks, where accesses are

inherently non-atomic, special hardware and software mechanisms must be employed to

assure sequential consistency. Here are the suficient conditions for sequential consistency

(as given in [13]) in systems with non-atomic accesses:

Sufficient Conditions for SC in Systems with Non-Atomic Accesses

(1) before a LOAD is allowed to perform with respect to any other processor, all previous

LOAD accesses must be globally performed and all previous STORE accesses must be per-

formed, and

(2) before a STORE is allowed to perform with respect to any other processor, all previ-

ous LOAD accesses must be globally performed and all previous STORE accesses must be

performed.

8.4.2 Consistency and Shared-Memory Architecture

Let us examine the consistency model for the common shared-memory architectures:

shared-bus systems without caches, shared-bus systems with caches, systems with gen-

eral interconnection networks without caches, and systems with general interconnection

networks with caches.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-75-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 71

only be consistent at those points.

Several memory consistency models that attempt to relax the constraints on the allowable

event orderings have been proposed and they are called relaxed consistency models. The

most prominent relaxed consistency models are the processor consistency, weak consis-

tency, and release consistency models. The larger latencies found in a distributed system,

as compared to a shared-bus system, favor the relaxed consistency models because they

allow more performant implementations than those allowed by the sequential consistency

model.

8.5 Processor Consistency Model

The processor consistency (PC) model requires that all writes issued from a processor may

be only observed in the order in which they were issued, but allows that the order in which

writes from two processors occur, as observed by themselves or a third processor, may not

be identical. The conditions for processor consistency are defined in [13] as follows:

Conditions for Processor Consistency

(1) before a LOAD is allowed to perform with respect to any other processor, all previous

LOAD accesses must be performed, and

(2) before a STORE is allowed to perform with respect to any other processor, all previous

accesses (LOADs and STOREs) must be performed.

The above conditions allow reads following a write to bypass the write. To avoid deadlock,

the implementation should guarantee that a write that appears previously in program order

will eventually perform. The PC model ignores all access labelings aside from sharedL.

8.6 Weak Consistency Model

The weak consistency model and the release consistency model (next Section) employ the

categorization and labeling of memory accesses (Section 8.2 and 8.3) to relax the event

ordering restrictions on the basis of extra information (provided by the programmer or

the compiler) on the type of memory access.

The weak consistency model proposed by Dubois et al. ([3]) is based on the idea that the

interaction between parallel processes manifests itself through synchronization accesses

that are used to order events and through ordinary shared accesses. If synchronization ac-

cesses can be recognized, and sequential consistency is guaranteed only for synchronization

accesses, then the ordinary accesses might proceed faster because they need to be ordered

only with respect to synchronization accesses. This improves performance because ordi-

nary accesses are more frequent than synchronization accesses. As an example, consider a

processor updating a data structure within a critical section. If updating the structure re-

quires several writes, each write in a sequentially consistent system will stall the processor

untill all other cached copies of that location have been invalidated. But these stalls are

unnecessary, as the programmer has already made sure that no other process can rely on

the consistency of that data structure until the critical section is exited. If the synchro-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-77-2048.jpg)

![72 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

nization points can be identified, then the memory need need only be consistent at those

points. The weak consistency model exploits this idea and guarantees that the memory

is consistent only following a synchronization operation. The conditions that ensure weak

consistency are given in [13]:

Conditions for Weak Consistency

(1) before an ordinary LOAD or STORE access is allowed to perform with respect to any

other processor, all previous synchronization accesses must be performed,

(2) before a synchronization access is allowed to perform with respect to any other pro-

cessor, all previous ordinary (LOADs and STOREs) accesses must be performed, and

(3) synchronization accesses are sequentially consistent with respect to one another.

Speaking in terms of access labeling, under the weak consistency model only the la-

bels sharedL, ordinaryL, and specialL are taken into account, with an access labeled as

specialL being treated as a synchronization access and as both an acquire and a release.

In a machine supporting weak consistency (also called weak ordering of events [3,13,17]) the

programmer should make no assumption about the order in which the events that a process

generates are observed by other processes between two explicit synchronization points.

Accesses to shared writable data should be executed in a mutually exclusive manner,

controlled by synchronization operations, such as LOCK and UNLOCK. Only synchronization

accesses are guaranteed to be sequentially consistent. Before a synchronization access

can proceed, all previous ordinary accesses must be allowed to “settle down” (i.e., all

shared memory accesses made before the synchronization point was encountered must be

completed before the synchronization access can proceed). In such systems we say that

events are weakly ordered.

The advantage of the weak consistency model is that it provides the user with a reasonable

programming model, while permitting multiple memory accesses to be pipelined, and thus

allowing high-performance. For example, consider a multiprocessor with a buffered, mul-

tistage, and packet-switched interconnection network. If strong ordering is to be enforced,

then the interface between the processor and the network can send global memory requests

only one at a time. The reason for this is that in such a network the access time is vari-

able and unpredictible because of conflicts; in many cases waiting for an acknowledgement

from the memory controller is the only way to ensure that global accesses are performed

in program order. In the case of weak ordering the interface can send the next global

access directly after the current global access has been latched ih the first stage of the

interconnection network, resulting in better processor efficiency. However, the frequency

of synchronization operations (such as LOCKs) will be higher in a program designed for a

weakly ordered system. Therefore, weak consistency is expected to be more performant

than sequential consistency in systems that do not synchronize frequently.

The disadvantage of the weak consistency model is that the programmer or the com-

piler must identify all synchronization accesses in order to support mutually exclusive

access to shared writable data. Moreover, the synchronization accesses must be hardware-

recognizable to enforce that they are sequentially consistent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-78-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 73

8.7 Release Consistency

The release consistency model (RC) is an extension of the weak consistency model, in

which the requirements on synchronization accesses and ordinary accesses ordering are

relaxed. The release consistency model exploits the information conveyed by the labels at

the leaves of the labeling tree, that is, the labelings ordinaryL, nsyncL, acqL, and relL

are considered by the model. Basically, RC guarantees that memory is consistent only

when a critical section is exited. The conditions for ensuring release consistency are given

in [13] as follows:

Conditions for Release Consistency

(1) before an ordinary LOAD or STORE access is allowed to perform with respect to any

other processor, all previous acquire accesses must be performed,

(2) before a release access is allowed to perform with respect to any other processor, all

previous ordinary (LOADs and STOREs) accesses must be performed, and

(3) special accesses are processor consistent with respect to one another.

The ordering condition stated by the weak consistency model for synchronization accesses

is extended under the release consistency model to special accesses, that include all compet-

ing accesses, both synchronization and non-synchronization accesses. On the other hand,

four of the ordering restrictions in weak consistency are not present in release consistency:

1. First, ordinary LOAD and STORE accesses following a release access do not have to wait

for the release access to be performed. Because the release synchronization access

is intended to signal that previous LOAD and STORE accesses in a critical section are

complete, it is not related to the ordering of the future accesses. Of course, the local

dependences within a processor must still be respected by LOADs and STOREs.

2. Second, an acquire synchronization access need not be delayed for previous ordinary

LOAD and STORE accesses to be performed. Because an acquire access is intended

to prevent future accesses by other processors to a set of shared locations, and is

not giving permission to any other process to access the previous pending locations,

there is no reason for the acquire to wait for the pending accesses to complete.

3. Third, a non-syncronization special access does not wait for previous ordinary ac-

cesses and does not delay future ordinary accesses; therefore, a non-synchronization

access does not interact with ordinary accesses.

4. Fourth, the special accesses are only required to be processor consistent and not

sequentially consistent. The reason for this is that, provided that the applications

meet some restrictions, sequential consistency and processor consistency for special

accesses give the same results. The restrictions that allow this relaxed requirement

on special accesses are given in [13] and have been verified there to hold for the

parallel applications available at the time the study has been conducted.

Essentially, RC guarantees that the memory is consistent when a critical section is exited,

by requiring that all ordinary memory operations be performed before the critical section](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-79-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 79

coherence protocols —write invalidate and write update— exhibit performance dependent

on the sharing pattern. Snooping protocols may use either write invalidate or write update,

while directory-based protocols use write invalidate. Write-invalidate schemes maintain

cache coherence by invalidating copies of a memory block when the block is modified by a

processor. For snooping-based protocols, the invalidation is broadcast and all caches are

checking if they have a copy of the line that must be invalidated, while for directory-based

protocols only the caches that actually share the line receive the invalidation message.

The sharing pattern is characterized by several parameters, of particular importance be-

ing the number of caches sharing a data object and the write-run. The write-run has

been defined by Eggers and Katz [18] as the length of the uninterrupted sequence of write

requests interspread with reads to a shared cache line by one processor. A write-run is

terminated when another processor reads or writes the same cache line. The length of

the write-run is the number of writes in that write-run. Every new write-run requires an

invalidation and data transfer. When write-runs are short, the write-invalidate scheme

generates frequent invalidations and the write update scheme generates equally frequent

updates. Since the total time cost for invalidations and data transfer is higher than the

cost of updating one word, write-invalidate schemes are inferior for this sharing pattern.

On the other hand, for long write-runs, the write update scheme generates many updates

that are redundant, given the length of the write-run. Therefore, write invalidate performs

better for long write-runs because only the first write in a write-run causes invalidation

of the shared copies of the written line. Furthermore, a write invalidate scheme in a

directory-based protocol sends one invalidation request per write-run only to the caches

that actually share the line. A study conducted on a simulated 32-processor machine [9]

shows that, for a large number of applications, most writes cause invalidations to only a

few caches, with only about 2% of all shared writes causing invalidation of more than 3

caches. Write invalidate protocols perform fairly well for a broad range of sharing pat-

terns. However, there exist some sharing patterns for which unnecessary invalidations are

generated. A notable example is the invalidation overhead associated with data structures

that are accessed within critical sections. Typically, processors read and modify such data

structures one at a time. Processors that access data this way cause a cache miss followed

by an invalidation request being sent to the cache attached to the processor that most

recently exited the critical section. This sharing behavior, denoted migratory sharing has

been previously shown to be the major source of single invalidations (i.e., invalidation of

one cache) by Gupta and Weber in [14]. An extension of the write-invalidate protocol

that effectively eliminates most single invalidations caused by migratory sharing has been

proposed by Stenstr¨om et al. in [19]. This scheme improves performance by reducing the

shared access penalty and the network traffic.

9.4 Snooping Protocols

9.4.1 Implementation Issues

A bus is a convenient device for ensuring cache coherence because it allows all processors

in the system to observe ongoing memory transactions. In a snooping protocol each cache

snoops on the transactions of other caches. When the cache controller sees an invalidation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-85-2048.jpg)

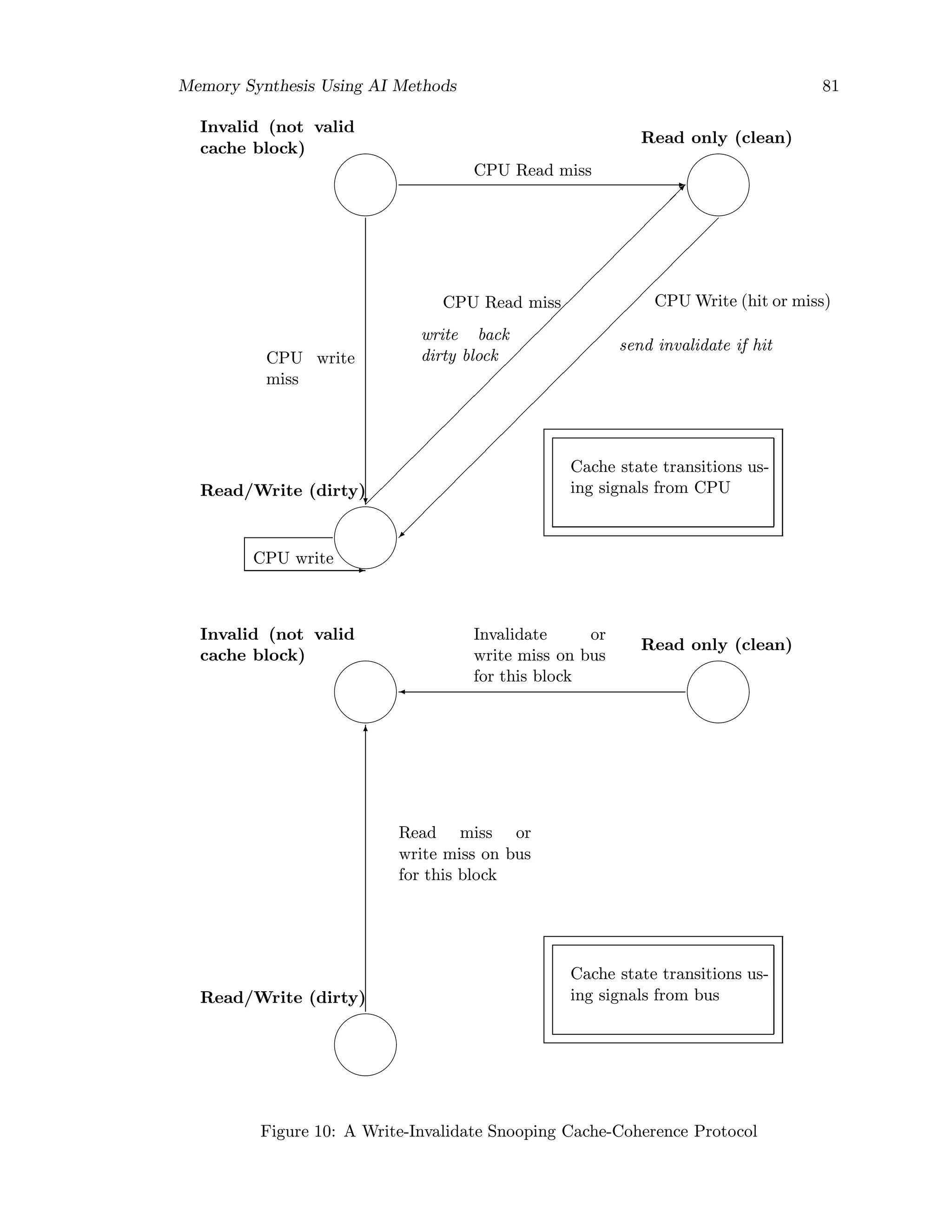

![82 Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods

There is only one state-machine in a cache, with stimuli coming either from the attached

CPU or from the bus, but the figure shows the three states of the protocol in duplicate

in order to distinguish the transitions based on CPU actions, as opposed to transitions

based on bus operations. Transitions happen on read misses, write misses, or write hits;

read hits do not change cache state.

When the CPU has a read miss, it will change the state of that block to Read only and

write back the old block if it was in the Read/Write state (dirty). All the caches snoop

on the read miss to see if this block is in their cache. If one cache has a copy and it is

in the Read/Write state, then the block is written to memory and is then changed to the

Invalid state (as shown in this protocol) or Read only.

When a CPU writes into a block, that block goes to the Read/Write state. If the write

was a hit, an invalidate signal goes out over the bus. Because caches monitor the bus, all

check to see if they have a copy of that block; if they do, they invalidate it. If the write

was a miss, all caches with copies go to the invalid state. For simplicity, write to clean

data may be treated as a “write miss”, so that there is no separate signal for invalidation,

but the same bus signal as for write miss is used.

9.4.3 Improving Performance of Snooping Protocol

Reducing Interference Between Broadcasts and CPU Operation

Since every bus transaction checks cache-address tags, it would interfere with the CPU

accesses to cache if only a copy of the address tag were accessed both by CPU and snooping.

To remove this problem, the address tag portion of the cache is duplicated so that an extra

read port is available for snooping; these two identical copies of the address tag are called

snoop tag and normal tag respectively. In this way, snooping interferes with the CPU’s

accesses to the cache only when the tags must be changed, that is, when the CPU has a

miss or when a coherence operation occurs. On a miss, the CPU arbitrates with the bus

to change the snoop tags as well as the normal tags (to keep the address tags coherent).

When a coherence operation occurs in the cache, the CPU will likely stall, since the cache

is unavailable.

Reducing Invalidation Interference

Some designs ([20]) are queuing the invalidation requests. A list of the addresses to be

invalidated is maintained in a small hardware-implemented queue called Buffer Invalida-

tion Address Stack (BIAS). The BIAS has a high priority for cache cycles, and if the

target line is found in the cache, it is invalidated. To reduce the interference between the

invalidation accesses to cache and the normal CPU accesses, a BIAS filter memory ([20])

may be used. A BFM is associated with each cache and works by filtering out repeated

requests to invalidate the same block in a cache.

Snooping protocols are fairly simple and not expensive. For multiprocessors with a small

number of processors they perform well. The disadvantage is that the snooping protocols

are not scalable. Buses don’t have the bandwidth to support a large number of processors.

The coherence traffic quickly increases with the number of processors because snooping

protocols require that all caches see every memory request from every processor. The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/memorysynthesisusingaimethods-201006184613/75/Memory-synthesis-using_ai_methods-88-2048.jpg)

![Memory Synthesis Using AI Methods 83

shared bus and the need to broadcast every memory request to all processor caches inher-

ently limit the scalability of snooping protocol-based machines, because the common bus

and the individual processor caches eventually saturate.