This document discusses approaches to regulating the legal profession and legal education. It makes several key points:

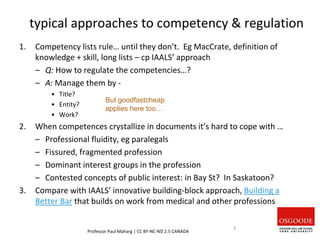

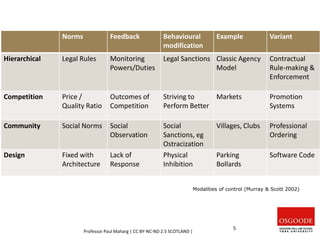

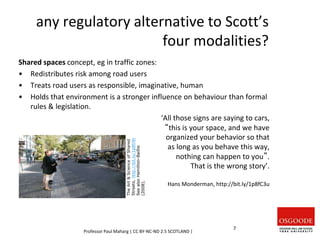

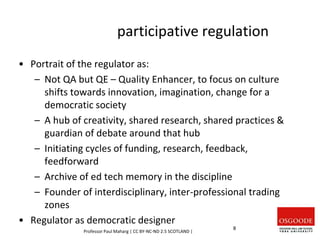

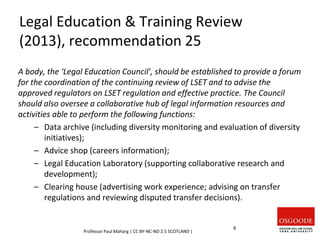

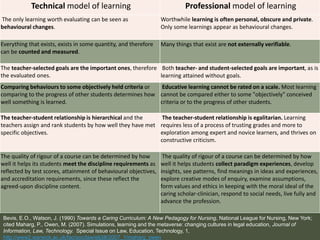

1. Established approaches to regulating competencies need to change as the profession becomes more fluid and fragmented. New approaches like shared space regulation and participative regulation may have a role to play.

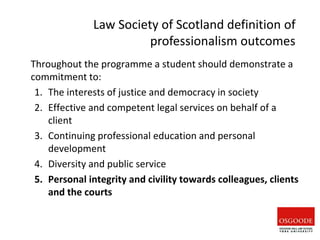

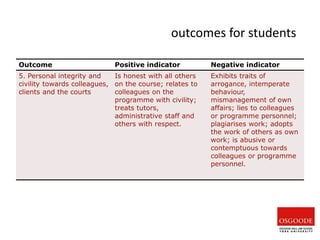

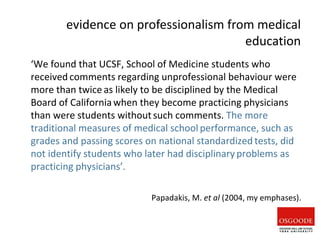

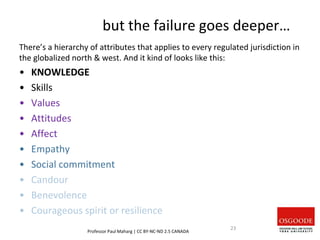

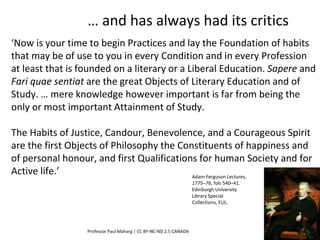

2. Professionalism is essential for regulation but insufficient on its own. Attributes like empathy, social commitment, and courageous spirit are also important but often overlooked in legal education and assessment.

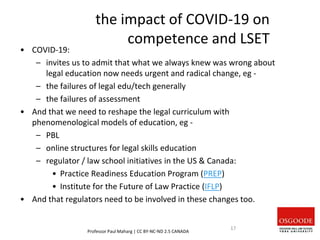

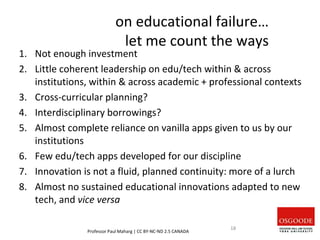

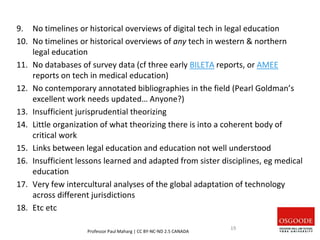

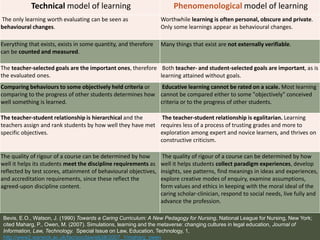

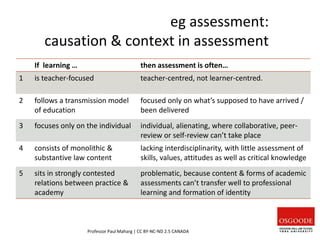

3. COVID-19 has revealed failures in legal education and technology that now require urgent and radical change, such as moving to more learner-centered phenomenological models of education.

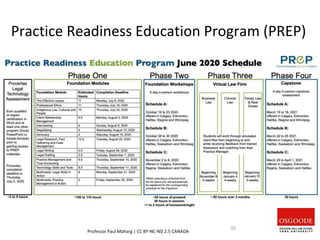

4. Three future examples are discussed where competence

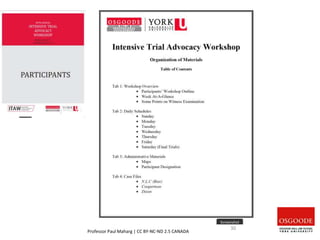

![ITAW: interim student feedback

• Simply great.

• I realise that my lack of prep is my fault only, so I preface my remarks

with this. I think that maybe a week prior, an hour or two prep session

taking us through Moodle, Slack, lesson prep, etc.?

• I really enjoyed how the faculty were able to separate us into smaller

groups so that they may directly critique our performance to get better

in examinations.

• Well managed. I liked the micro presentation. Don’t have to bite off too

much. Most importantly, I learned at least one major thing today that

will start to benefit my practice immediately. Job well done. Only

negative comment is a better understanding of where [zoom room] to

go in next, which was not clear.

• The first day of the program went really well. The program was planned

really well. There were no issues with technology, timing, etc. even

though this is the first time it is being offered virtually. All the instructors

gave valuable feedback and simplified the processes involved in direct,

cross, and re-examination.

Professor Paul Maharg | CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 CANADA

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lsopresentation27-210127212629/85/Lso-presentation-27-1-21-32-320.jpg)