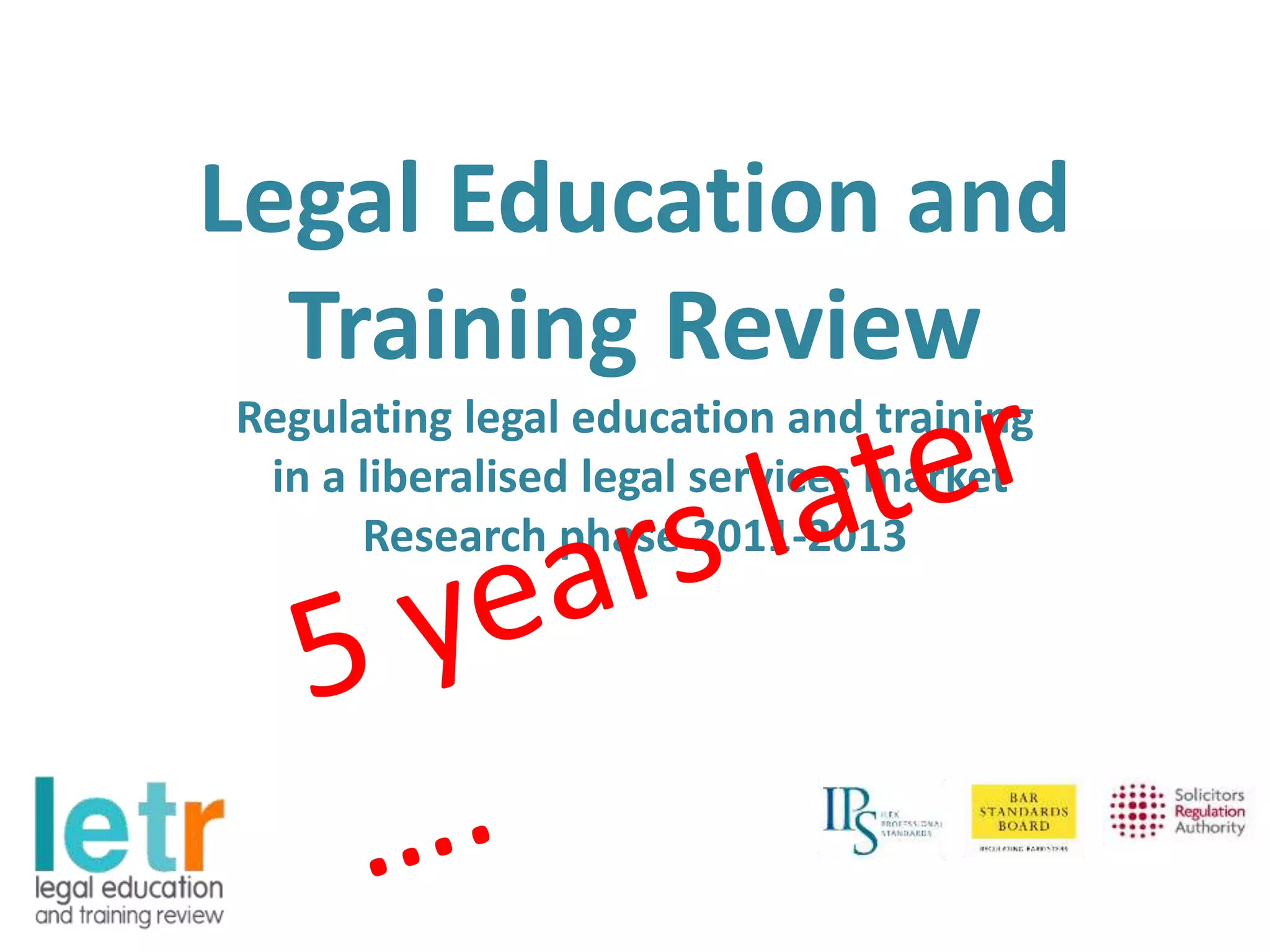

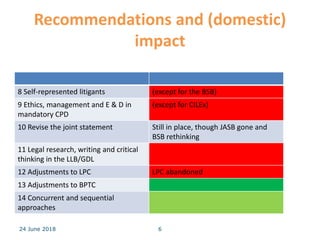

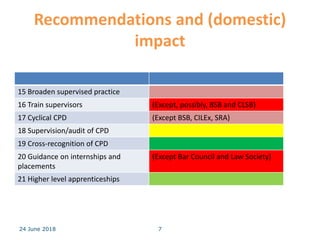

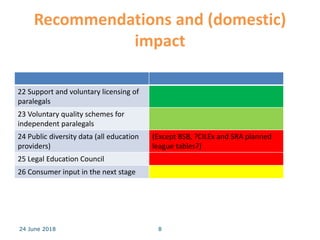

This document summarizes the key findings and recommendations from a project called the Legal Education and Training Review (LETR) that assessed legal education and training systems in England and Wales. The summary includes:

1) The LETR project aimed to help regulators develop legal education policies by assessing existing education programs, identifying required skills, and making recommendations to make education more responsive to emerging needs.

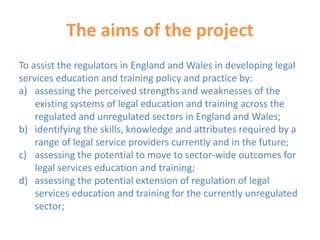

2) The LETR made several recommendations related to learning outcomes, standards, competencies, coordination between regulators, and expanding the regulatory framework to include unregulated sectors. Many of these recommendations were adopted by the regulators.

3) Continuing issues discussed include ensuring diversity and inclusion, defining competencies needed in the 21st century,

![Equality, diversity and social mobility

• “Your CV looks good, but you don’t speak enough languages. You

haven’t travelled”.

• “.. I can’t afford to travel places, I’m trying to pay debts? … I’m sorry I

couldn’t go to Cambodia.” LETR data (2013)

• “…[E]mployers too often expect persons to have certain character

traits or to have certain experiences that are linked to their

background. She said in an interview she was asked ‘why she hadn’t

been travelling', when this was not something she could afford”. All

Party Parliamentary Committee (2017)

24 June 2018 11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/letr5yearslaterfinal24062018-180624214828/85/Letr-5-years-later-final-2406-2018-11-320.jpg)

![Shared space

Shared spaces concept in traffic zones:

• Redistributes risk among road users

• Treats road users as responsible, imaginative, human

• Holds that environment is a stronger influence on behaviour

than formal rules & legislation.

‘All those [road]signs are saying to cars, “this is your space, and we have

organized your behaviour so that as long as you behave this way, nothing

can happen to you”. That is the wrong story’.

Hans Monderman, http://www.pps.org/reference/hans-monderman/

De Brinke, Oosterwalde, The Netherlands. In Hamilton-Baillie, B. (2008).

Shared space: reconciling people, places and traffic. Built Environment,

34, 2, 161-81, 168, fig.7.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/letr5yearslaterfinal24062018-180624214828/85/Letr-5-years-later-final-2406-2018-15-320.jpg)

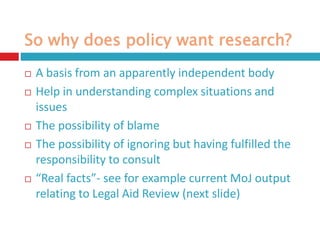

![Give us your hard figures, LASPO

review team urges

By Monidipa Fouzder18 June 2018, Law Society Gazette

The Ministry of Justice has asked practitioners to 'be a bit more

open' with hard data to inform an ongoing review of the

government's controversial legal aid reforms.

The ministry has discussed the impact of the Legal Aid, Sentencing

and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO) with more than 50

organisations so far as part of its post-implementation review, due to

be completed this year.

Asked at a LASPO review conference last week about the scale of the

data the MoJ review team wants to incorporate into the review,

Matthew Shelley, the ministry's deputy director for legal support and

court fees, said 'a lot of data' is collected by the ministry and HM

Courts & Tribunals Service. However, when evidence is requested

from the sector, the information is 'largely anecdotal'.

'Yet you must collect your own data and it's hard to get access to that

data, to release the data [you] hold. My plea is to be a bit more open

about that information to inform our review,' Shelley said.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/letr5yearslaterfinal24062018-180624214828/85/Letr-5-years-later-final-2406-2018-26-320.jpg)