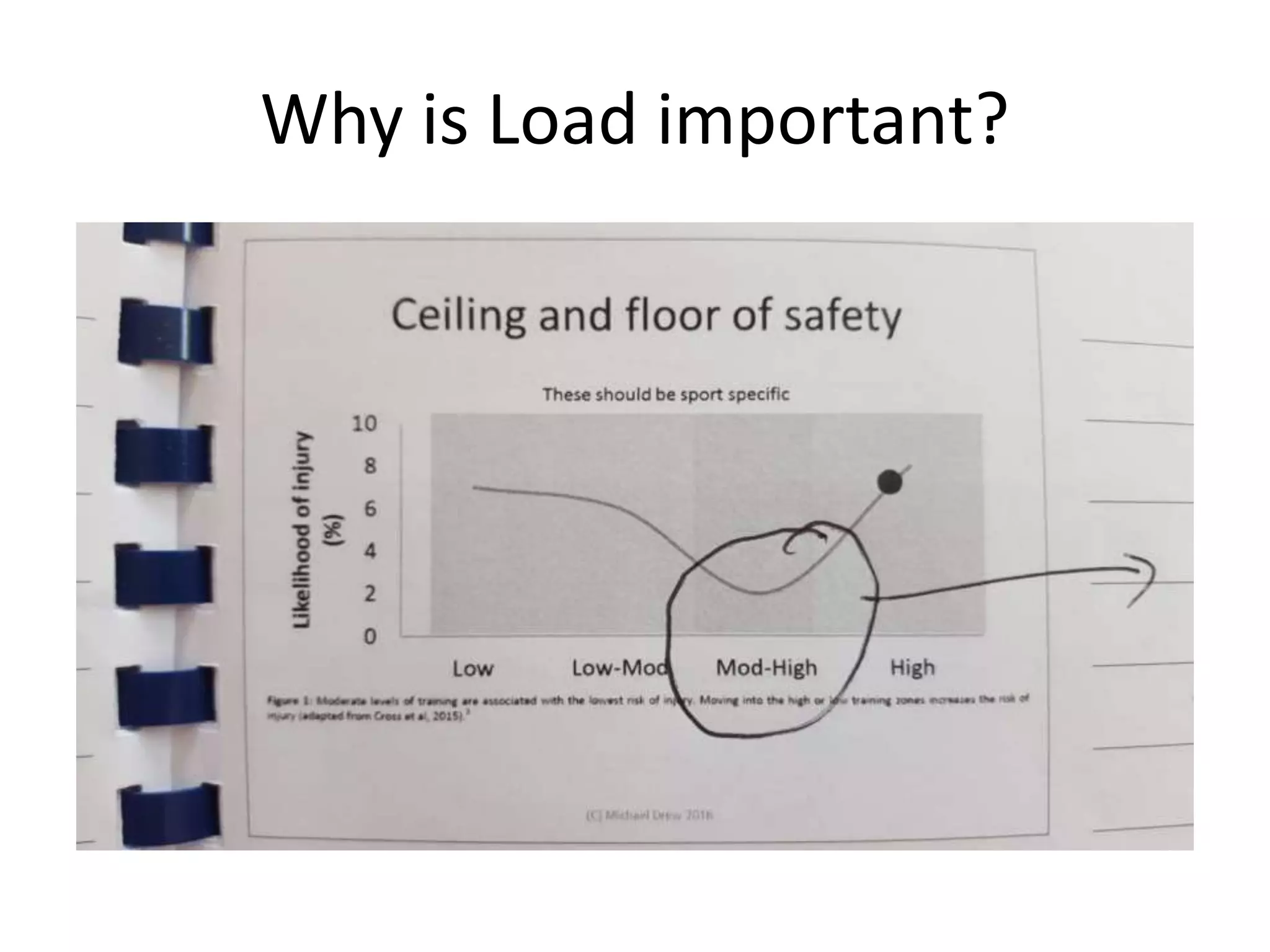

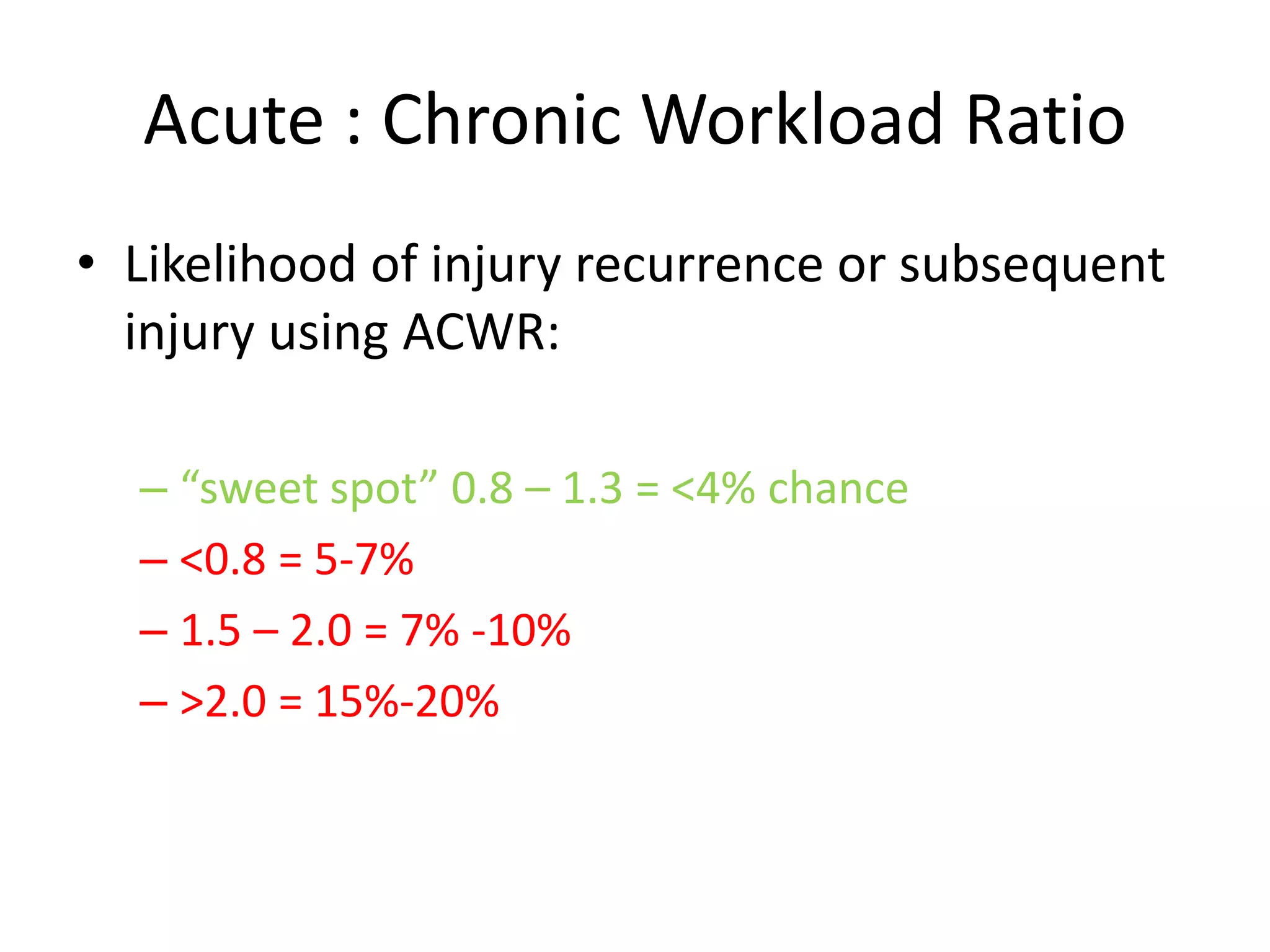

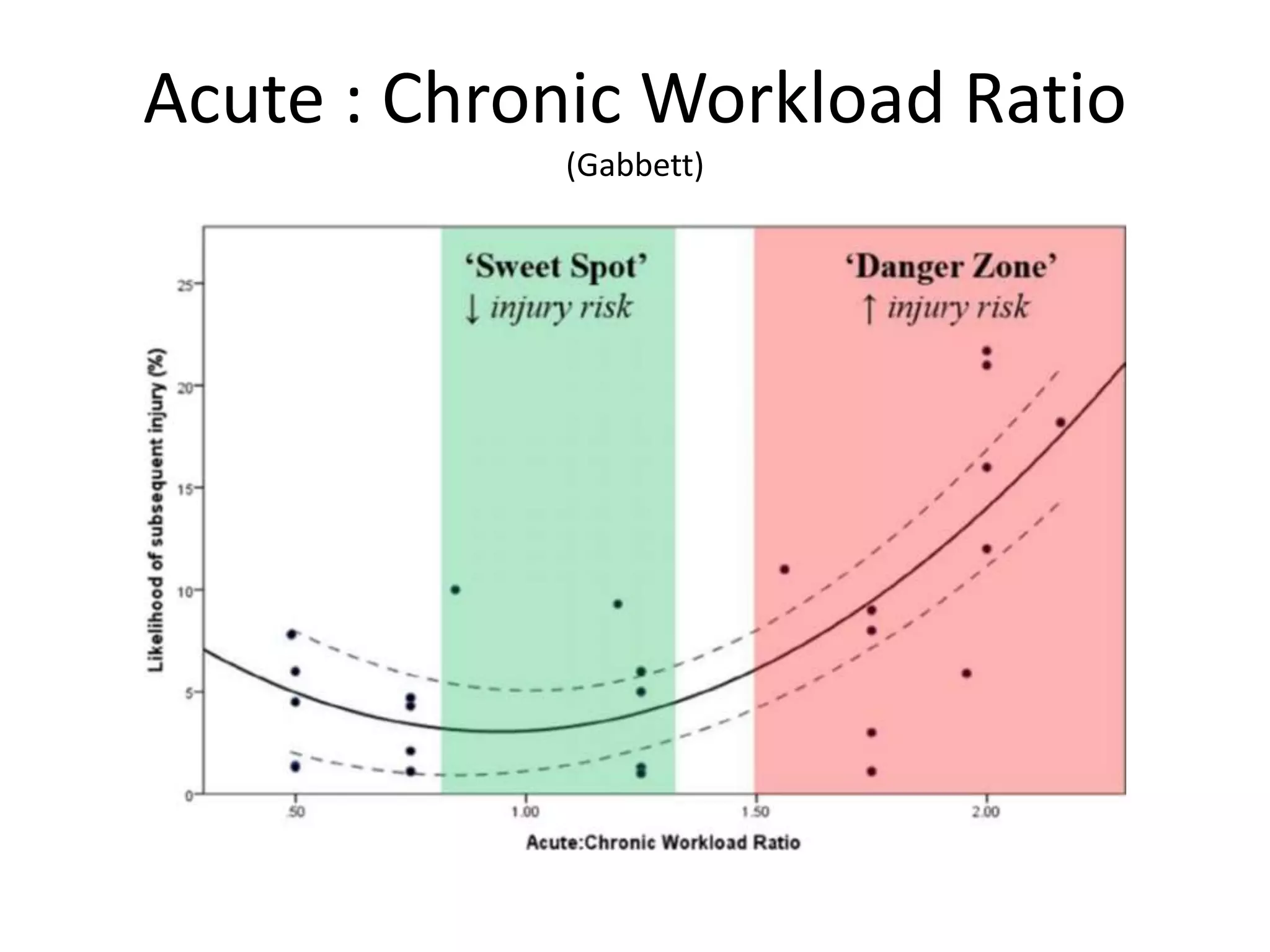

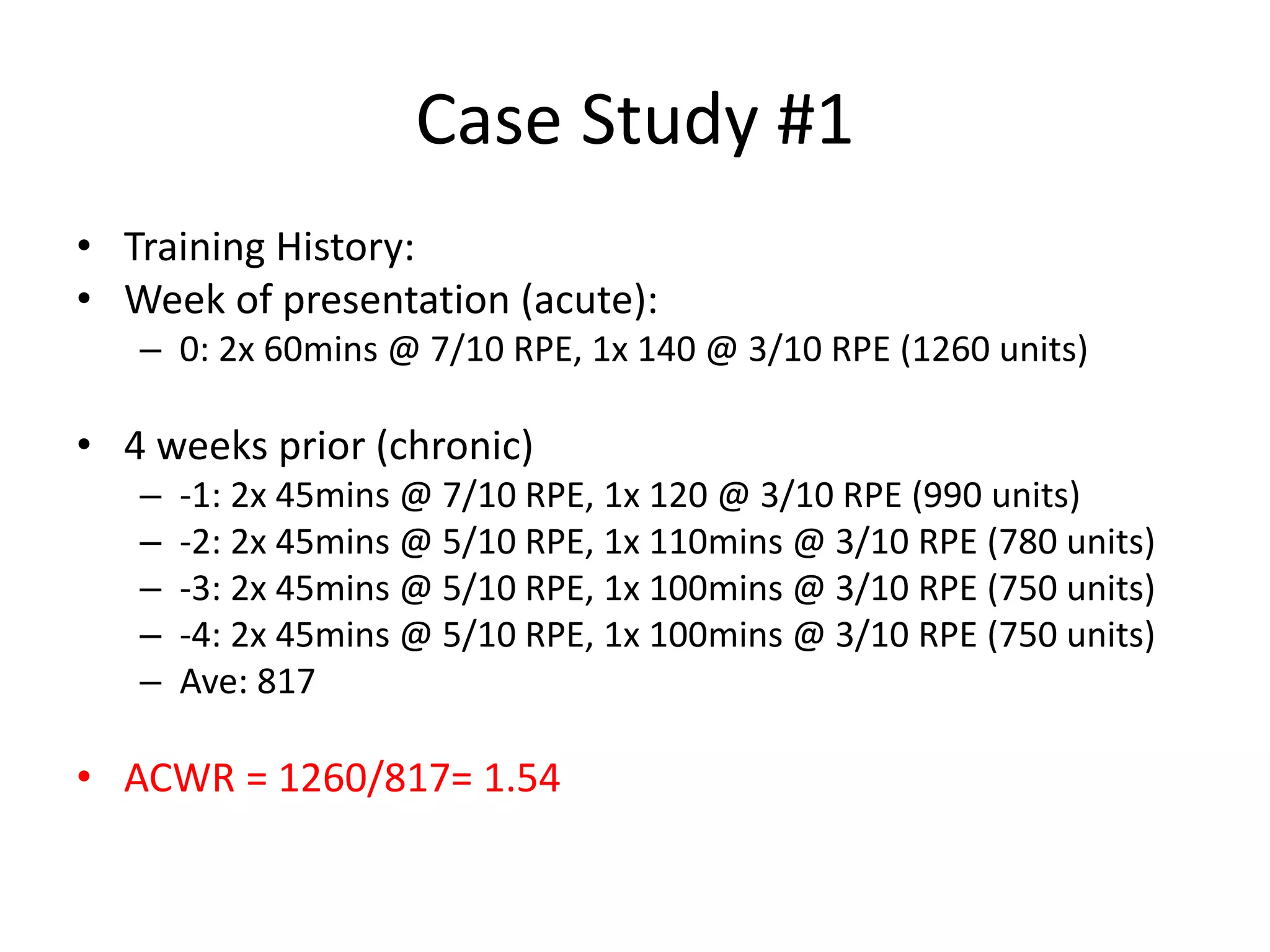

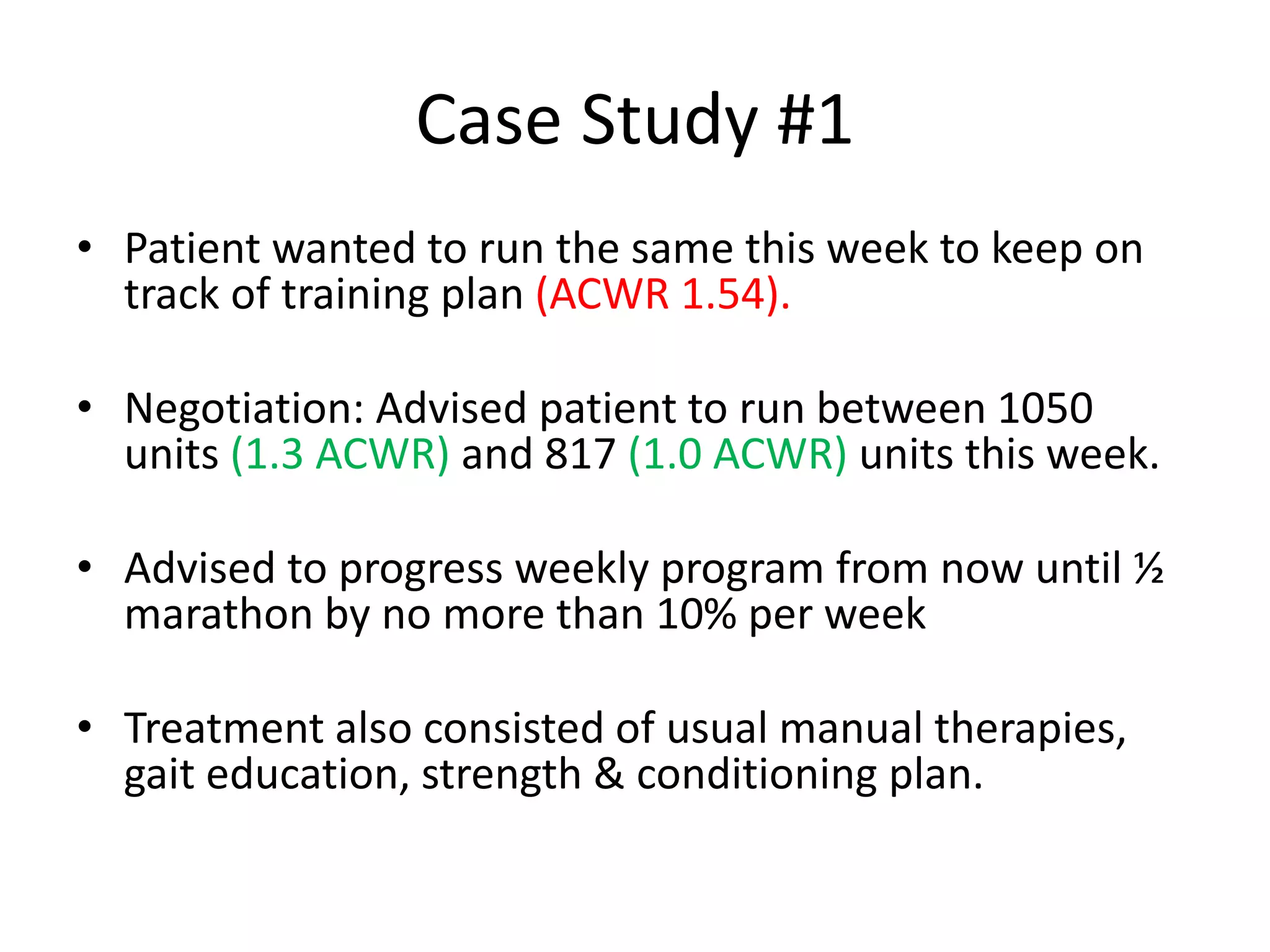

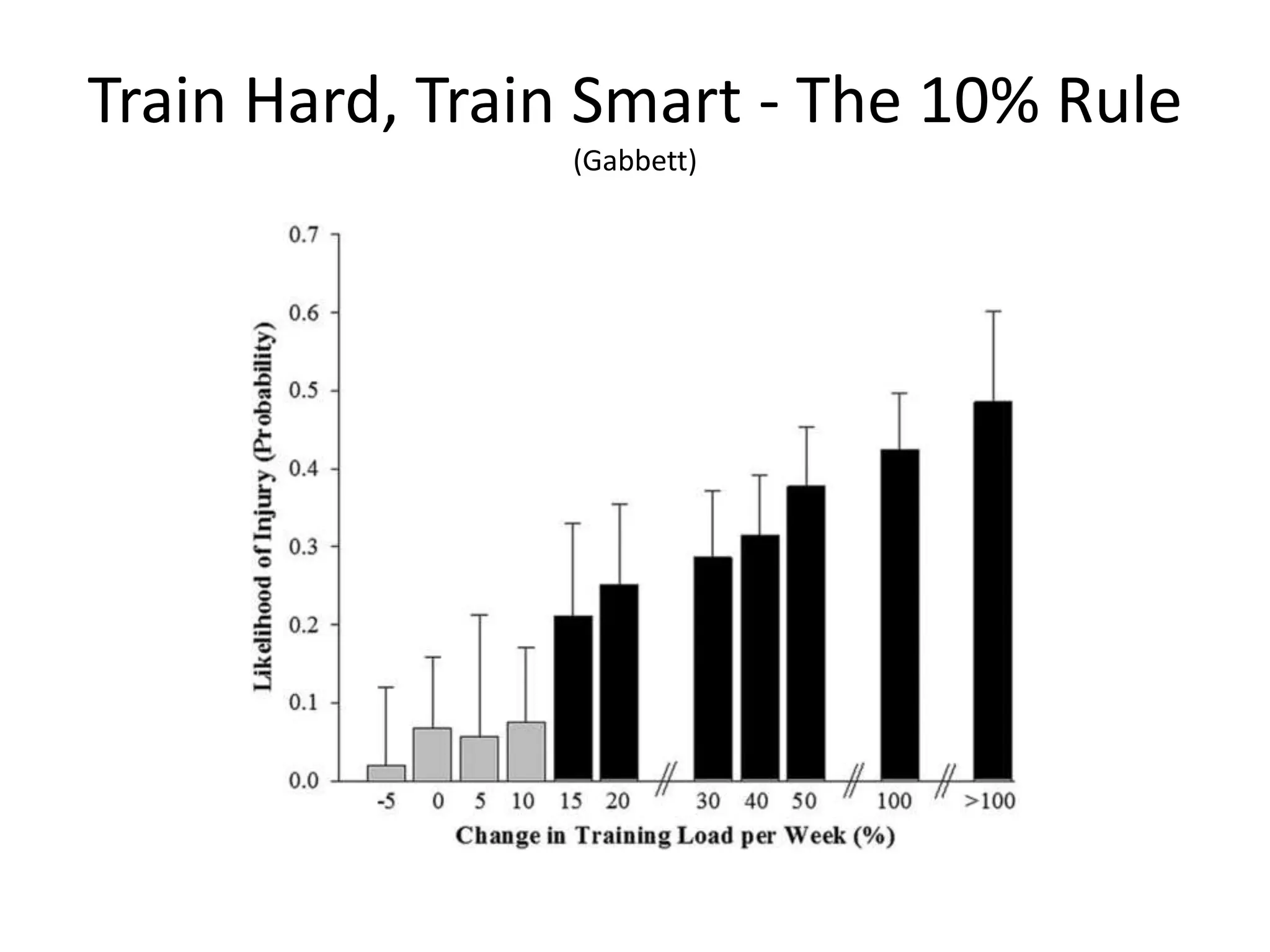

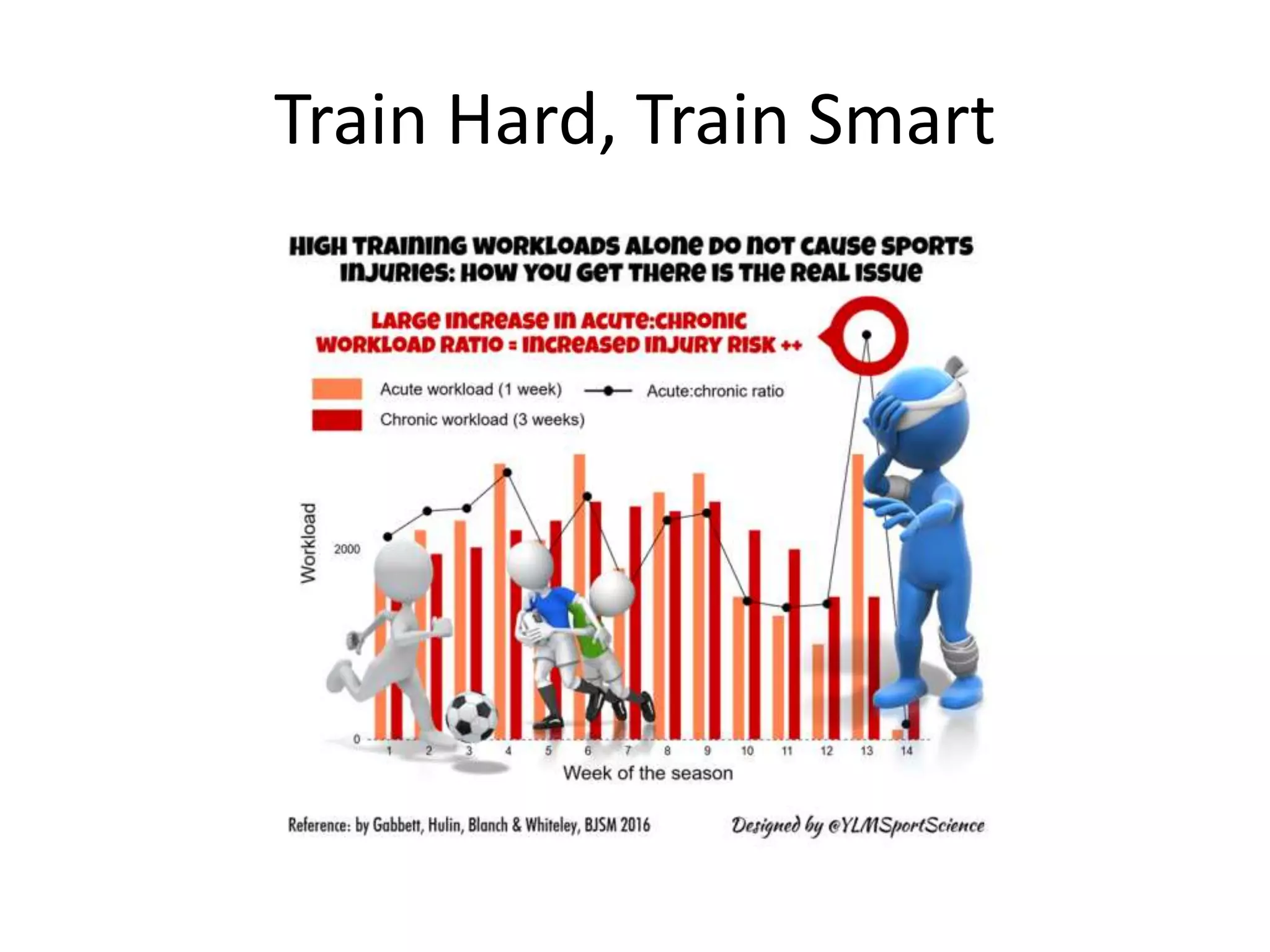

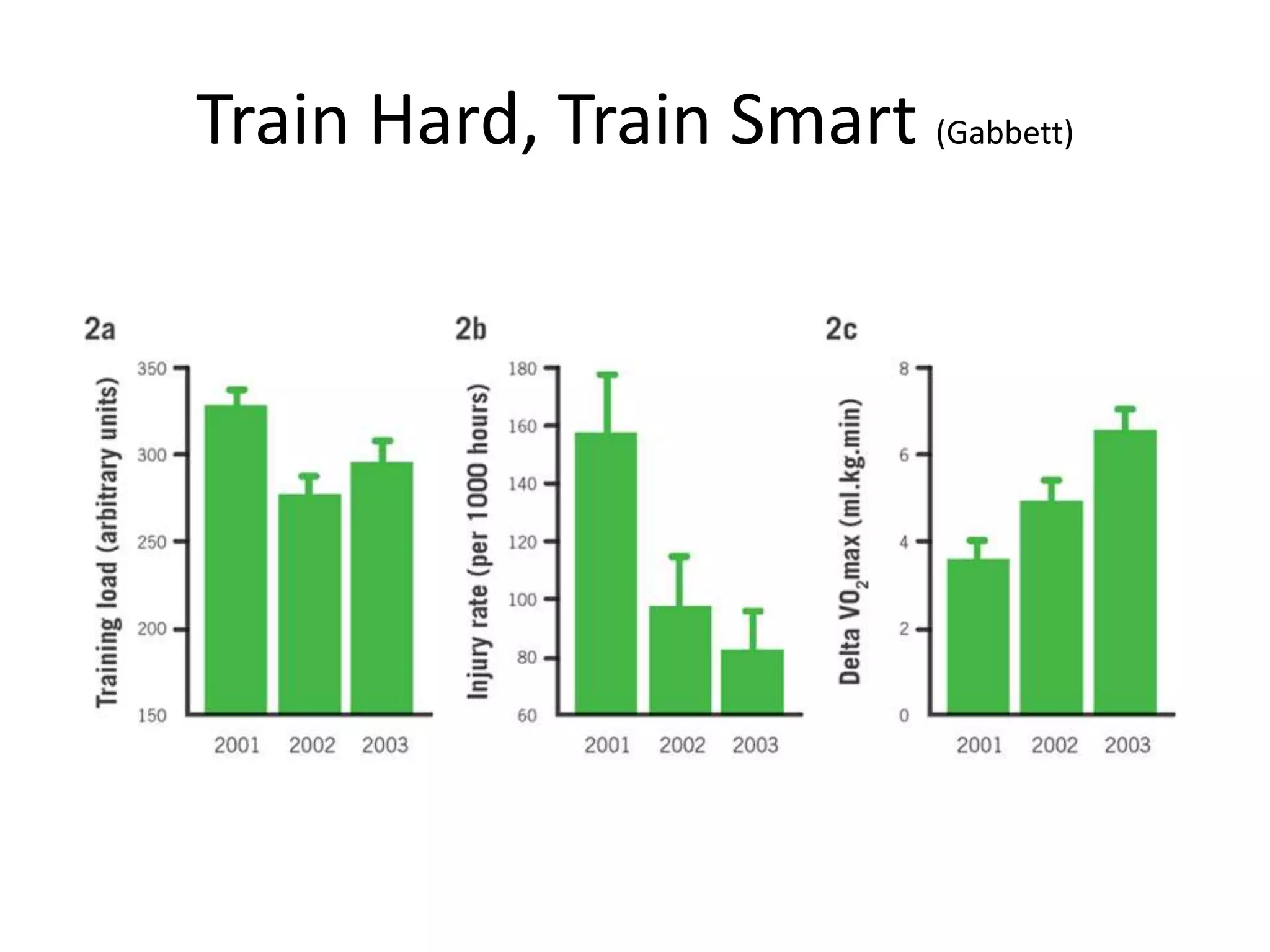

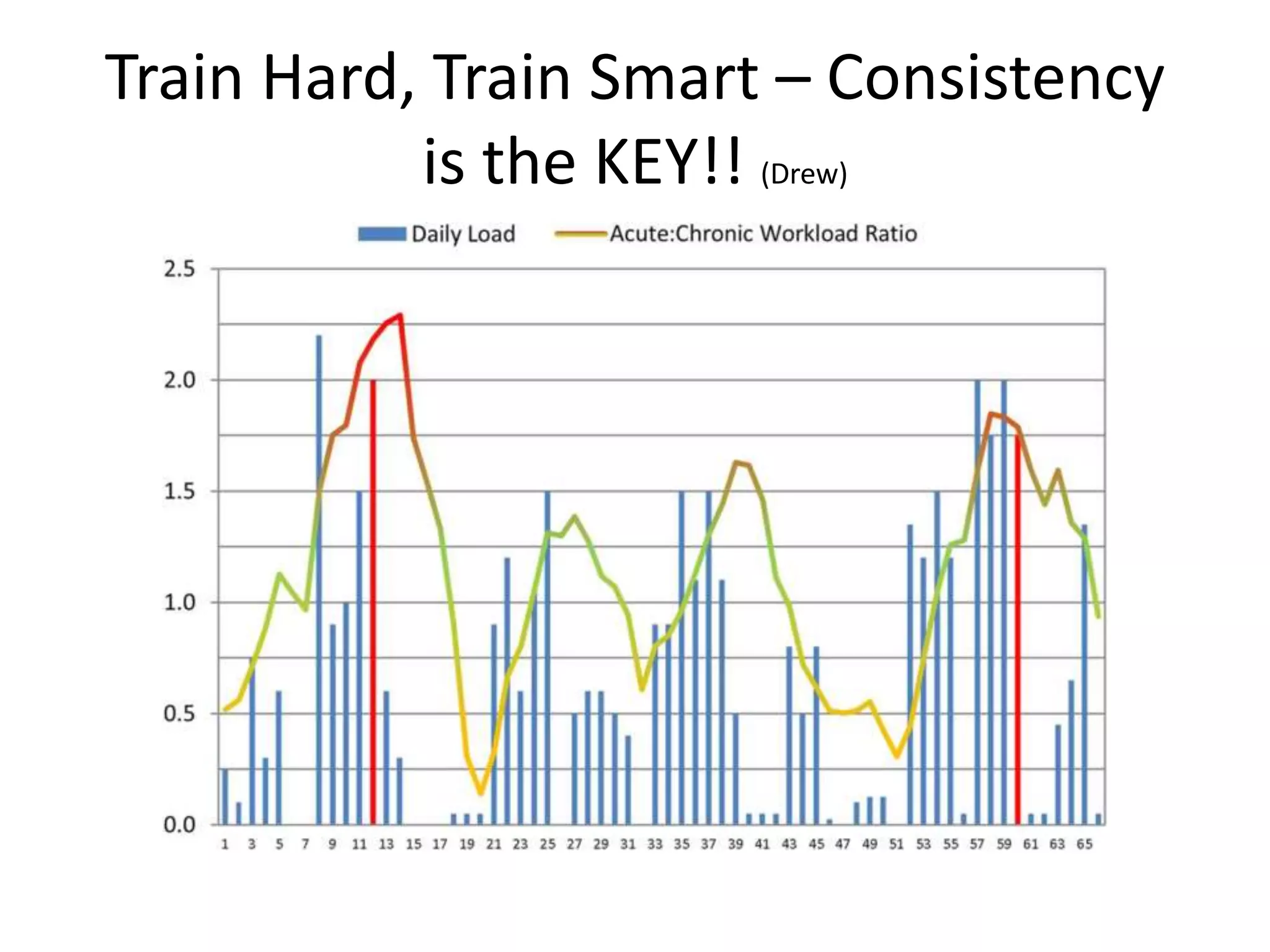

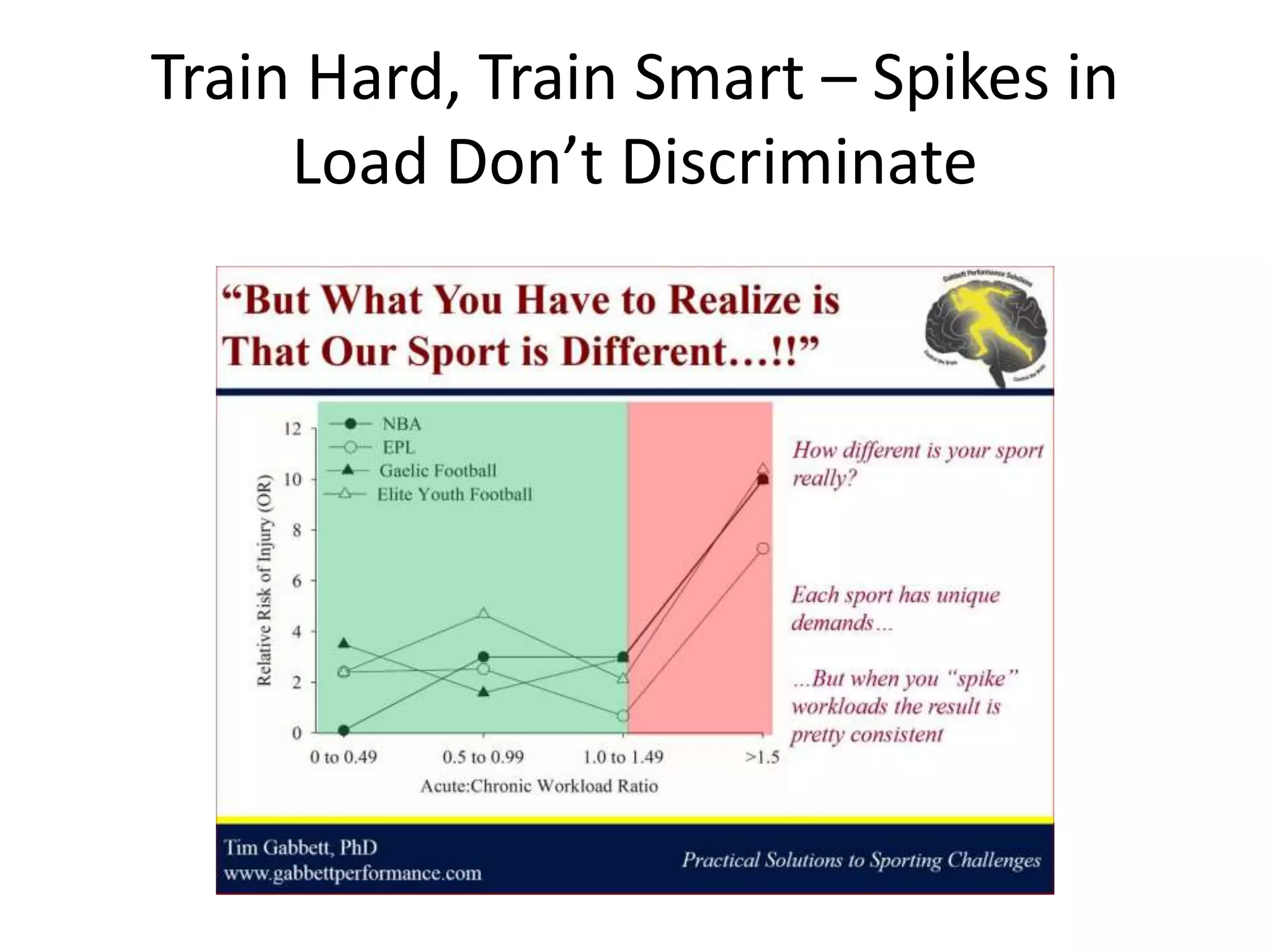

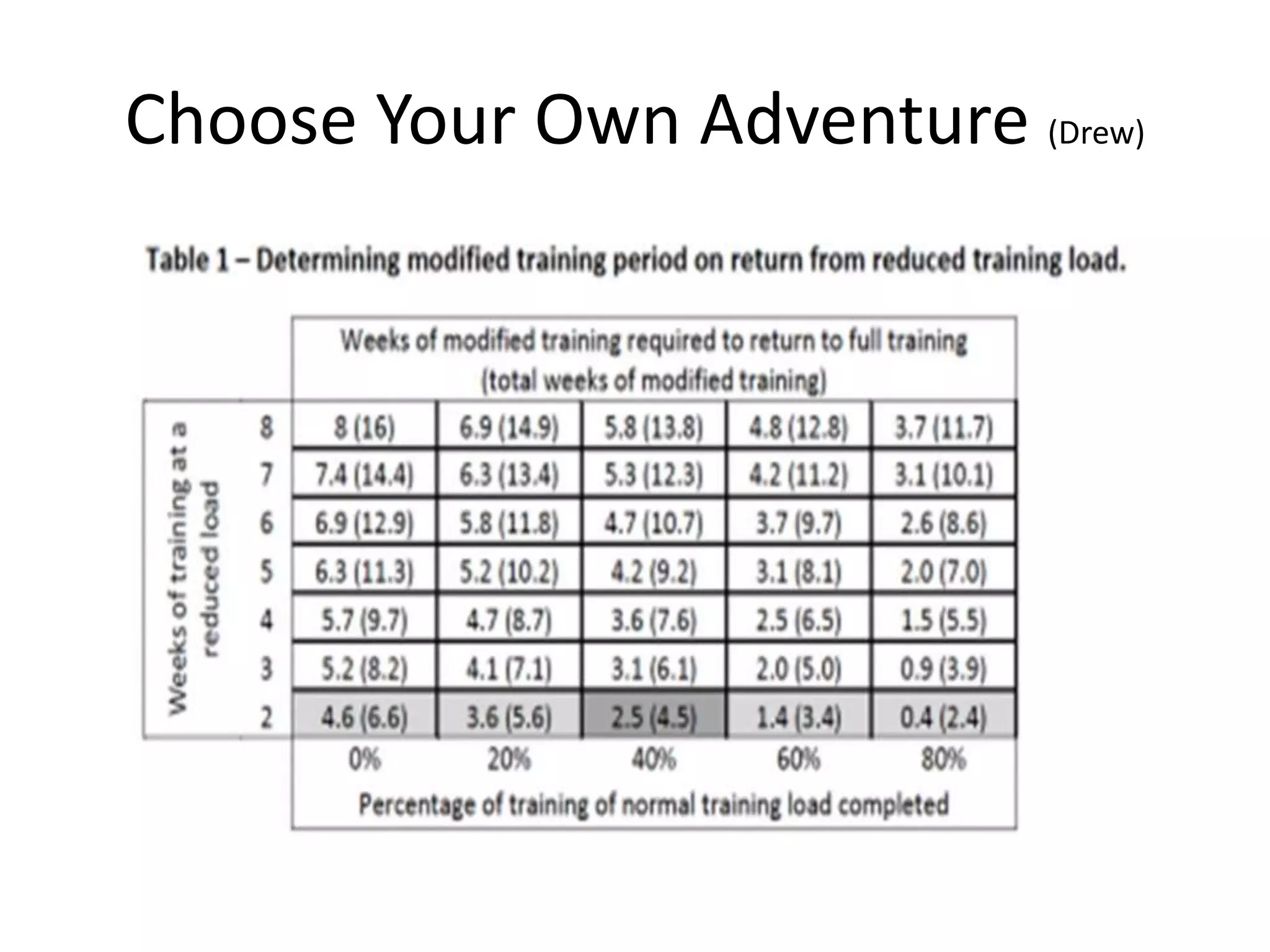

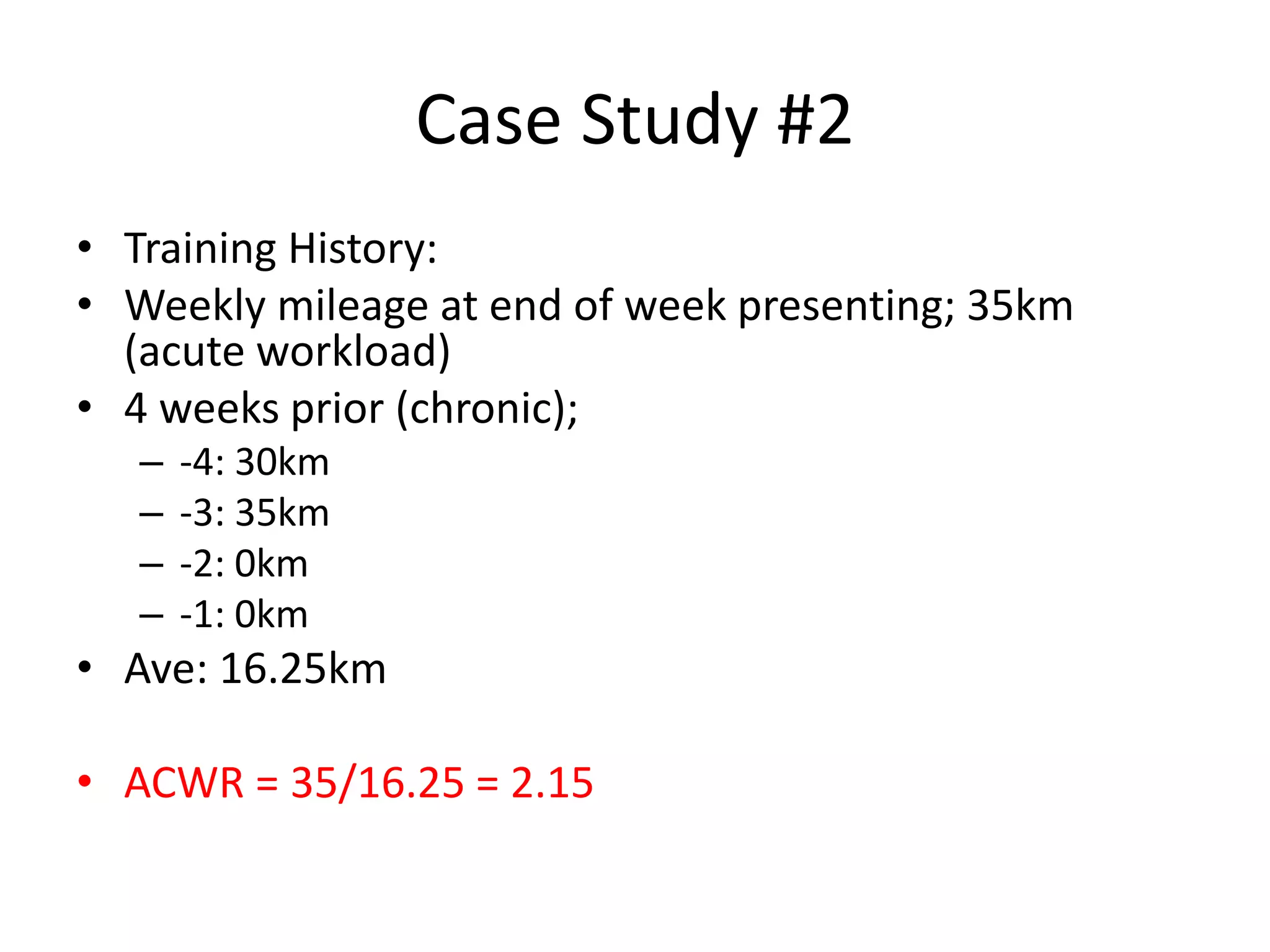

The document discusses load management and its importance for injury prevention. It defines load as both external measures like distance run and internal measures like heart rate. The Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) compares an athlete's recent weekly load to their average load over the previous 4 weeks and can predict injury risk. An ACWR of 0.8-1.3 has the lowest injury risk, while over 2.0 has the highest. The document provides examples of calculating ACWR and modifying training based on this metric. It emphasizes gradually building load no more than 10% per week to minimize injury risk.