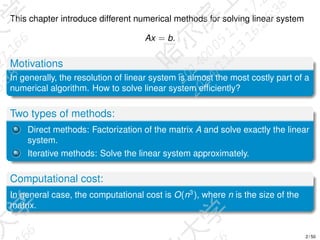

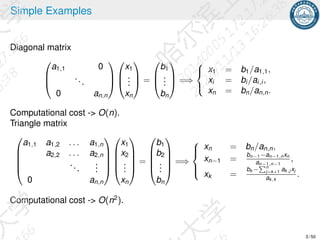

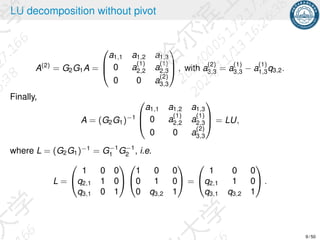

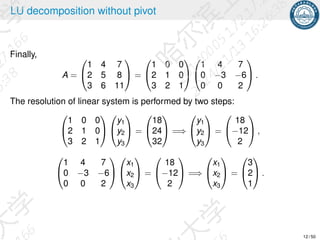

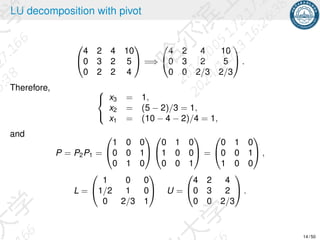

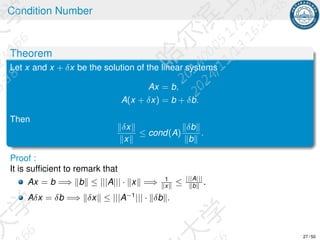

The document discusses numerical methods for solving linear systems of equations, focusing on direct and iterative methods, with computational costs generally being O(n^3). It covers techniques such as LU decomposition, both with and without pivoting, and introduces Cholesky decomposition for positive definite matrices. The document emphasizes efficiency and stability in solving systems while providing examples and algorithms for practical application.

![Conjugate Gradient Method

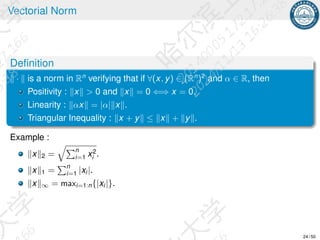

Definition

Assume A positive definite, if {p0, p1, . . . , pn−1} is Rn

, satisfying

Api , pj = 0, i ̸= j, then {p0, p1, . . . , pn−1} are A-conjugate.

Different from the gradient method, now we search the A-conjugate descent

directions.

Assume that the direction p0, p1, . . . , pk−1 are given and A-conjugate, we

search pk such that {p0, p1, . . . , pk } are A-conjugate. We decompose

x = y + αpk , where y ∈ span{p0, p1, . . . , pk−1}, α ∈ R.

J(x) = J(y + αpk )

= J(y) +

α2

2

Apk , pk −α b, pk , (since Ay, pk = 0)

min

x∈span{p0,p1,...,pk }

J(x) = min

y,α

J(y + αpk )

= min

y

J(y) + min

α

[

α2

2

Apk , pk −α b, pk ].

45 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linearsystem-241128090012-a8c1299a/85/Linear_system-Linear_system-Linear_system-pdf-45-320.jpg)

![Conjugate Gradient Method

The solution of min

y

J(y) is y = xk .

The solution of min

α

[

α2

2

Apk , pk −α b, pk ] is

αk =

b, pk

Apk , pk

=

b − Axk , pk

Apk , pk

=

rk , pk

Apk , pk

.

Moreover, we assume that pk = rk + βk−1pk−1.

By using the fact pk , Apk−1 = 0, we obtain

βk−1 = −

rk , Apk−1

pk−1, Apk−1

.

46 / 50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linearsystem-241128090012-a8c1299a/85/Linear_system-Linear_system-Linear_system-pdf-46-320.jpg)