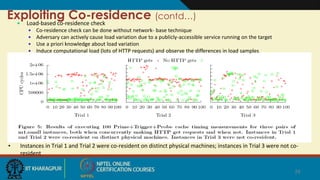

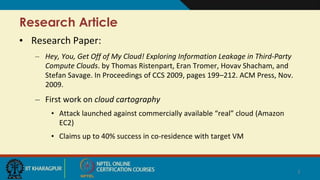

The document summarizes research on security risks in cloud computing due to multi-tenancy. It discusses how researchers were able to:

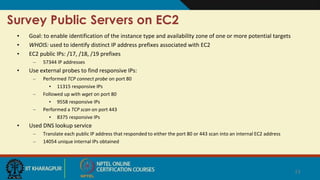

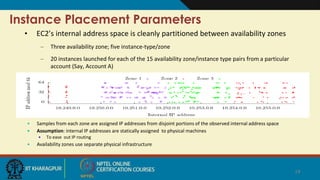

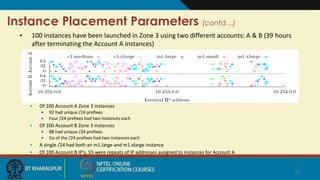

1) Map the physical layout of Amazon EC2 instances to determine placement parameters to achieve co-residence with target VMs.

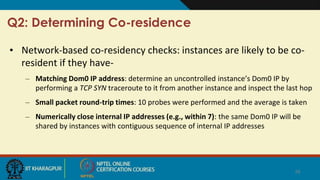

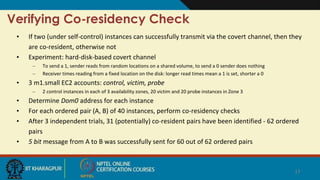

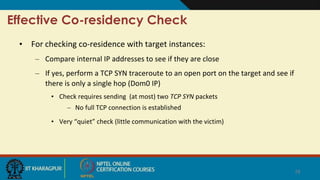

2) Verify co-residence through network checks and a covert channel with over 60% success.

3) Cause co-residence by launching many probes or targeting recently launched instances, achieving up to 40% success.

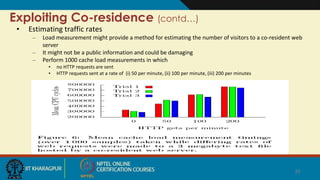

4) Exploit co-residence to measure cache usage and network traffic, allowing for load monitoring and covert channels to leak information.

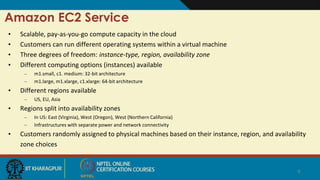

![Amazon EC2 Service (contd…)

• Xen hypervisor

– Domain0 (Dom0): privileged virtual machine

• Manages guest images

• Provisions physical resources

• Access control rights

• Configured to route packets for its guest images and reports itself as a hop in traceroutes.

– When an instance is launched, it is assigned to a single physical machine for its lifetime

• Each instance is assigned internal and external IP addresses and domain names

– External IP: public IPv4 address [IP: 75.101.210.100/domain name: ec2-75-101-210-100.compute-1.amazonaws.com]

– Internal IP: RFC 1918 private address [IP: 10.252.146.52/domain name: domU-12-31-38-00-8D-C6.compute-1.internal]

• Within the cloud, both domain names resolve to the internal IP address

• Outside the cloud, external name is mapped to the external IP address

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture28-cc-security3-191010165704/85/Lecture28-cc-security3-10-320.jpg)